M

Julia E. Ferrin, Florette McGuire, Annie McGuire McDowell, Lorna Cummins, Roberta Flake Clayton, Anna Thompson, Emma Orrilla Perry Merrill, Mary Helen Packer Bryce Merrill, Henrietta Pearce Hall Steers Minnerly, and Sophia Isadora Morris Pomeroy, "M," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 417-478.

Clara Amelia Wall Matthews

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Clara Amelia Wall

Birth: February 15, 1858; Springville, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: Frederick John Wall and Elizabeth Robinson

Marriage: David Henry Matthews;[1] May 5, 1874

Children: David Joseph (1875), George Augustus (1877), Polly Elizabeth (1878), Daniel Alonzo (1887)

Death: November 3, 1939; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Glenbar, Graham Co., Arizona

Clara Amelia Wall was born in Springville, Utah, February 15, 1858. As a child she moved with her parents to Santaquin, Utah, where she met and married David Henry Matthews. They were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, Utah May 5, 1874, by Daniel H. Wells.[2]

She spent her early married life in Santaquin, where her first three children were born: David Joseph, March 19, 1875; George Augustus, January 31, 1877; Polly Elizabeth, October 11, 1878.

She and her husband and children moved to Arizona with her husband’s father, Joseph Lazarus Matthews, and his family. Little Polly celebrated her second birthday on the journey. They spent their first year in Pima, which was then called Smithville. Clara’s husband, his father, and three brothers, Frank, Daniel, and Charley, bought a ranch located about four miles west of Pima on the Gila River. Their home was a stockade house made from logs cut from the cottonwood trees that grew along the river. These logs were about ten feet long and were twelve to eighteen inches in diameter; a trench about twelve inches deep was dug, and the logs were stood on end and made to fit as closely as possible. Any cracks between the logs were chinked up with mud mixed with straw. The roof was made by first laying logs across from wall to wall. Smaller logs were then laid crosswise, then willows or cattails, and finally a layer of dirt. When it rained, it was a problem to keep the roof from leaking, but in the spring the roof was beautiful with weeds and wild flowers.

A ward was organized called the Matthews Ward. David Henry served as bishop, and Clara was Relief Society president.[3] When the family first moved to the ranch, Geronimo, the Apache chief, was on the warpath. In 1887, he was captured by the government and shipped to Florida.

Clara’s third son, Daniel Alonzo, was born in Matthews July 18, 1887. Prior to that time, her husband built her a new home of hand-planed cottonwood logs with a shingle roof and a board floor. When Lon was seven years old, the family moved into a two-story adobe house.

Clara lived on the ranch and raised her family, going through all the excitement and hardships of any early pioneer mother. She was an excellent cook and nearly always had a houseful of company. She was a great comfort and help in times of sickness and childbirth. Women in confinement sent for Clara before they called the doctor. On one occasion when the birth was difficult, the doctor laid the baby aside as stillborn. Clara carried the baby into the kitchen, dipped its body first into warm then cold water, massaged it limbs, and breathed her breath into its mouth. The doctor was amazed when the baby cried, and asked Clara to bring it into the room because hearing it cry and knowing that it was alive would give the mother the will to live.[4]

Two of Clara’s sons filled missions for the Church. George was called to the southern states after he was married and the father of two children. A third child was born while he was gone. His wife and children lived with Clara and her husband during the two years George served as a missionary. Lon filled a thirty-month mission in Germany. When he returned, Clara met him in Salt Lake. At this time she saw her brothers and sisters and other members of her family for the first time since coming to Arizona.

Clara’s husband passed away in Matthews, December 22, 1919. After his death, Clara continued to live in her home with her son Lon and his family.

In January 1923 she moved to Phoenix with them. At one time she rented a room in Mesa near the temple where she worked for a short time. She had a small house built in Pima near the home of her granddaughter Debra Dean and her husband Clifford. While living in Pima, Clara fell [on October 16, 1939] and broke her hip. She never survived the shock and died November 4, 1939.[5] She was nearly eighty-two years old.

Ellis and Boone:

When the earliest settlers came into the Gila Valley, all supplies had to come by freight wagons from Tucson or Silver City, New Mexico. The Southern Pacific Railway arrived at Willcox in 1880, making it possible for merchants to ship their wares by rail to Willcox, but freight wagons were still required to get the items to Thatcher and Safford.[6] In Arizona, many Mormon men used their horses, mules, or oxen to haul freight from railheads to isolated settlements—from Holbrook to Fort Apache, from Benson to Tombstone and/

In the Gila Valley, these big freight wagons also carried supplies, particularly coke for the smelters, from Willcox or Bowie to the mining town of Globe. On the return trip, the wagons hauled copper ingots to the railhead. One of these freighters, Peter Howard McBride, was also a poet who would sing a “tongue-in-cheek” song called “Freighting from Willcox to Globe.” Two stanzas illustrate this trip; some of the language and activities in other stanzas is slightly out of harmony with Latter-day Saint teachings.

Come all you jolly freighters

That has freighted on the road,

That has hauled a load of freight

From Willcox to Globe;

We freighted on this road

For sixteen years or more

A-hauling freight for Livermore,—

No wonder that I’m poor.

Now I have freighted in the sand,

I have freighted in the rain,

I have bogged my wagons down

And dug them out again;

I have worked both late and early

Till I was almost dead,

And I have spent some night sleeping

In an Arizona bed.[7]

When the Matthews family moved into the adobe ranch house (after 1894), their home was located on this freight route. They had “a good well and windmill. The Matthews home was a regular stop for water, meals and a change of horses for the stage coach on the route between Globe and Bowie. Freighters also stopped for water and meals.”[8] Clara provided many of the meals for these freighters.

Freighting, and the income it provided for Mormon men, lasted longer in the Gila Valley than in other areas of Arizona. As railroad historian David Myrick wrote, “A quarter of a century elapsed between the time the first silver claims were located and the time the first train arrived in Globe.”[9] Although a rail route had been discussed earlier, the Gila Valley, Globe, and Northern Railway (GVG&N Railway) did not begin constructing track from Bowie to Globe until 1893. The railroad reached Solomonville in early August 1894 and Pima in October; trains immediately began bringing merchandise to the valley and made travel for the pioneers much easier. GVG&N track laying continued on toward Globe, reaching Fort Thomas in February 1895, and then construction was at an impasse. Five miles further east was the border of the San Carlos Apache Reservation, and an agreement with the Apaches seemed unattainable. Around Christmas of 1895, the railroad constructed five more miles of track, and the town of Geronimo sprang up on the border of the reservation, complete with stock yards facilitating the shipment of cattle. For two years, freighters plied their trade transporting goods from Geronimo to Globe. Finally, an agreement was reached with the Apaches in February 1898, and construction of track resumed. The first regular passenger train arrived at Globe on December 1, 1898, thus ending freighting in the Gila Valley.[10]

Elizabeth Clark McBride

Julia E. Ferrin[11]

Maiden Name: Elizabeth Clark

Birth: October 1, 1846; Wolverhampton, Staffordshire, England

Parents: Edward Watkins Clark and Lucy Ashby

Marriage: James Andrew McBride; February 18, 1866

Children: James Andrew (1866),[12] William Edward (1868), Don Carlos (1871), Frank Ashby (1873), Sarah Elizabeth (1875), Jesse Burt (1878), Lucy Agnes (1880), John Henry (1883), Phoebe Leila (1886), Rollo (1888), Susan Nellie (1890), Julia Ellise (1893)

Death: September 25, 1935;[13] Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

My mother, Elizabeth Clark McBride, was born on October 1, 1846, in Wolverhampton, Staffordshire, England. She was a tiny little girl with blue eyes and brown hair—and a sunny disposition. Her father, Edward Watkin Clark, and mother, Lucy Ashby Clark, became dissatisfied with conditions in England and decided to go to Australia. So they took their small family and went to London. As I remember my grandfather, he was a little, white-haired merry Englishman whom we all loved. Grandmother was very proud and dignified.

After arriving in London, they went to live with a Brother and Sister Taylor, who taught them the gospel. They were baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on November 23, 1847. They were then called to be missionaries and go back to their home in Wolverhampton. There they preached the gospel and helped raise up a large branch, but there was much opposition. James Bell was president of the branch. They were very successful in their endeavors, and in December 1850, they set sail for America with a group of 400 Saints. On January 8, 1851, a great storm overtook them, making a great deal of them ill, and then an ocean liner rammed their ship. This accident broke their ship’s bow, split main yard and fore yard, and several minor things. This was very serious, but fortunately they were able to make it into a harbor called Cardigan Bay in Wales.

Grandfather was a joiner, or carpenter, and helped in repairing the ship. They were able to resume their journey in three weeks’ time.

There were many amusing things that happened on shipboard, and I remember my mother telling how she wandered into the supply room and pulled the bung out of a barrel of molasses. This, of course, was not too serious, but was rather amusing. After eighteen weeks of sailing from Liverpool, they arrived in New Orleans on March 14, 1851.[14]

In New Orleans, they embarked on a steamboat up the Missouri River and arrived in Council Bluffs. There they had to arrange for travel and so fixed up an outfit and started for the mountains in 1852. This outfit consisted of my grandfather, grandmother, and their four children, one yoke of oxen, and one cow. There were twenty companies of Saints, and Grandfather was in the first ten, with Henry Miller as captain over a company of fifty wagons.[15]

During the trip, Mother’s oldest sister was run over by a wagon and died the next day.[16] She was buried on the plains. This was a great trial to all of the family but did not deter them from going on, and they arrived in Salt Lake in September 1852. They stopped in Salt Lake to attend conference on October 10. This was very wonderful and inspirational to them. Then they moved on to Provo, Utah.

Here the Indians were very hostile and killed one man in Payson. Grandfather belonged to the militia and of course went out to Payson to help quell the uprising. It was several weeks before peace was restored.

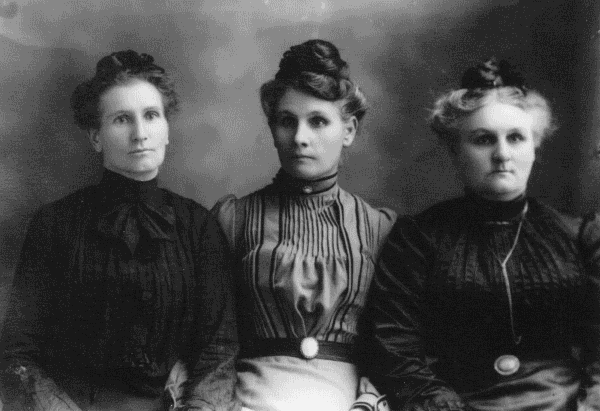

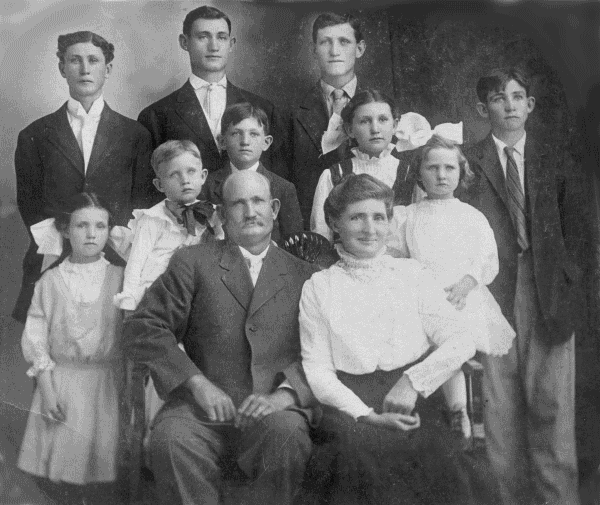

Elizabeth Clark McBride with her daughters, from left: Ellsie McBride Ferrin, Lucy McBride Taylor, and Lizzie McBride Cluff. Photo courtesy of Barbara Cornia.

Elizabeth Clark McBride with her daughters, from left: Ellsie McBride Ferrin, Lucy McBride Taylor, and Lizzie McBride Cluff. Photo courtesy of Barbara Cornia.

My grandmother was a very brave woman to rear her children under such circumstances, as they had many visits from the Indians who were hungry. Grandfather was away a great deal of the time, and she was pretty nervous at hearing strange noises. Grandmother would investigate noises even in the night, thinking it was better to know what was going on than to be wondering. During the time my mother was growing up, they had the grasshopper war in 1855, then the famine of 1856 when they lived on fish and roots. It was then Mother found a large fish caught in shallow water and dragged it home over her shoulder. The fish was as long as she was tall.

It was also in this time that the Lord provided sugar in the form of a white sticky substance that came overnight on all of the shrubs and bushes around. The people broke off the bushes or limbs and dipped them in water.[17] Then they made a sweet syrup by boiling it down. They used this in place of sugar. My mother learned to depend on the Lord in her early girlhood, and she never let her faith die; even in her old age she relied upon the Lord and asked special blessings, never doubting that she would receive them.

During her girlhood, the great Reformation took place, and all of the Saints vowed to live their religion.[18]

In 1848 James Andrew McBride came to Salt Lake with his family from Ohio and, when he grew to manhood, met my mother. They were married on February 18, 1866. From this union there were born twelve children, sometimes under the worst pioneer conditions, for they left Provo in 1880 for St. Johns, Arizona. Later on they moved to Smithville or Pima, Arizona, on the Gila River.

On their trip to Arizona, they had the usual trouble with the Indians that most pioneers had. At one time the Indians visited them on the road and discovered Mother’s little girl, Lucy, had red hair. Like most red-haired babies, she was a very pretty child, and the red hair seemed to captivate the Indians, for they wanted to trade horses for the baby. That, of course, was out of the question, but they hung around the wagon for several days making life very miserable for Mother. She was afraid that they would steal the baby; however, no harm came to them.

At one time they were camped on the Blue River while Father worked there in the lumber trade, and they lived in the wagon box with a cover over it. Mother missed one of the little boys. She finally found him sitting on the ground a short distance from the wagon—completely surrounded by small blue snakes. He was very quiet and seemed to be partially hypnotized. She was very frightened and did not know whether they were poisonous. She was afraid to startle him or the snakes for fear they would strike at him. So she spoke very softly to him again and again until she got his attention, then reached over and took his hand, pulled him slowly to his feet, and lifted him clear of the snakes. This shows you how very brave and resourceful my mother was.

After moving to Pima, Arizona, in 1881, Father built the first house with doors, windows, and a wooden floor in that town. Father was a counselor to Bishop John Taylor for fifteen years, then was a high councilman under Andrew Kimball for ten years.

Mother entertained many of the visiting brethren from Salt Lake in her home. She was a staunch Latter-day Saint and acted as a Primary and religion class leader and visiting teacher. She was able to do this while caring for her twelve children and Father’s brother and his three sons. It was a hard life, and Mother was frail, but she was able to get along. She did the best that she knew how and was always an inspiration to her boys and girls who needed her help and advice. Our home was a very happy one, with rag carpets on the floor and lovely knitted pillow cases. Also there were lace doilies on the chairs and tables—all of which Mother had made herself. Mother seemed to have had plenty of time to visit with her friends, and she gave big dinners for Father and his friends, as he loved to entertain.

Father freighted goods from Bowie, Arizona, to Globe, Arizona, and during this time the Apaches were not too friendly. They caused lots of trouble, killing and scaring people whom they met. At one time word came to Mother that Father and her brother William Clark had been killed while passing through the reservation on one of their freighting trips.

Mother had a sixth sense, or so she called it, that was a gift of knowing or seeing into the future. Consequently, while the others were grieving about the tragedy, she went about her work, telling them that all would be well and that Father had not been killed. Father soon came home. The Indians had run off their horses and threatened them, but nothing more serious had happened. Father was called out to fight Indians many times, and Mother had several frightening experiences before the Indians were subdued.

Father and Mother lived together for fifty-six years, then Father died on December 22, 1922. Her brother, Jed Clark,[19] then came to live with Mother, and about that time Mother had a special blessing given to her by Patriarch Nicholsen.[20] She was very much worried concerning her health and feared she would be ill a long time or have to suffer a long time. He gave her a blessing and a promise that she would never be dependent on anyone and that she would not suffer any ill health. This blessing really came to pass. She lived for that blessing and received it—for she was able to walk to town and back (about four blocks) the day that she died. Still doing her own housekeeping for two, still as cheerful as always, and only realizing a small distress in her stomach, she quietly passed away on September 25, 1935.

Ellis and Boone:

The description of crossing the Atlantic Ocean is an excellent example of a secondhand account. There are errors with the dates and spellings, but the story has enough details that it is possible to almost certainly identify the vessel without seeing the manifest. The British ship Ellen boarded a company of 466 Latter-day Saints on January 6, 1851, and left Liverpool two days later. After only twelve hours at sea, the ship collided with a schooner but was able to reach Cardigan Bay, North Wales, where repairs were made over a three-week period. The Ellen reached New Orleans on March 14. The Saints on the ship were divided into twelve wards, and it may be that James Bell was president of the Clarks’ ward.[21]

Because the women in this volume represent every area of Mormon settlement in Arizona, and therefore their lives touch nearly every important aspect of Mormon history, one more addition should probably be made to this sketch—the part Elizabeth played in the Wham robbery trial. When personal histories were being assembled for the Pima centennial book, Pioneer Town, Elizabeth’s granddaughter Elsie McBride Cluff wrote the following:

Memories of my Grandmother McBride are very fond. She was a very small petite lady with white hair. I, as a young girl, seemed to tower above her. She was always wanting to give me good gifts or a piece of pie or cake she had baked, and I loved to listen to stories she and Uncle Jed told as I sat with them in the long summer evenings on their front porch. Uncle Jed was Grandma’s younger brother and I thought it was a good joke when he would call her his little sister and tell us how he had to take care of her.

Grandma gave birth to twelve children, three of those babies died in infancy or in early childhood. When they came to Pima in December of 1881 they had a family of six children. One child had died previously. Their first home was a tent, then a one room adobe house was put up. This, according to information received, was one of the first houses in Pima to have a board floor, shingle roof, and a glass window. The walls were plastered clay and in one side was a large fireplace. A room made from lumber was added later. Sometime in the 80’s a robbery occurred and Grandma was thought to have known who the robbers were. (Perhaps this was the Wham robbers.) She was taken to Tucson as a witness against the robbers. She was kept there for several weeks and when paid off she brought home a table, chairs and other things that she had bought with the money.

The Wham Paymaster Robbery near Pima occurred on May 11, 1889, as the army payroll was being carried between Fort Grant and Fort Thomas. It was almost certainly carried out by men of the Gila Valley, but everyone was acquitted at the trial in Tucson, and no one in Graham County was willing to talk about who was involved in the robbery.[22]

Eliza McBride Cluff concluded describing her grandmother: “Grandmother entertained many of the visiting brethren from Salt Lake City in her home. She was a staunch Latter-day Saint and served as a Primary and Religion Class leader and a Relief Society visiting teacher. She loved to visit the sick and was always found at the bedside of a child or grandchild who was ill. In the early days when Pima had the largest meeting place in the Stake, Conference was held here. People came in horse drawn buggies and in wagons. Grandma took them in at noon and fed many of them.”[23]

Mary Jane McRae McGuire

Florette McGuire and Annie McGuire McDowell[24]

Maiden Name: Mary Jane “Mamie” McRae

Birth: May 23, 1876; Charleston, Wasatch Co., Utah

Parents: Joseph McRae and Maria Taylor[25]

Marriage: John Sidney McGuire; November 28, 1900

Children: Clare (1902), Sidney Kilby (1903), Florence (1905), Louis Taylor (1906), Ellen (1909), Annie (1912), Florette (1914), David McRae (1916), Mary (1916)[26]

Death: January 17, 1954; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Mary Jane “Mamie” McRae was born May 23, 1876, in Charleston, Wasatch County, Utah. She was the second daughter and sixth child of Joseph and Maria Taylor McRae, and granddaughter of Alexander McRae, who was with the Prophet Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail. Her father was brought to Liberty Jail to be blessed by the Prophet, and he gave him his name.

Her grandmother, Eunice Fitzgerald McRae, made many a trip to the jail to carry messages and notes of importance, hidden or sewed in her clothes, which the Church authorities had given her to carry to the Prophet, who was in chains. Many a time notes were also carried in the baby’s clothing and also food was sent to them in this manner. The testimony that her grandfather received from the close association with the Prophet, and his spiritual power and influence, was always a guide in his life.

Mamie’s father attended a conference in Salt Lake City, planning to buy lumber and return with it to complete their home, but he instead returned with a “call” from President Brigham Young to a thirteen-year mission to pioneer Arizona. Her mother’s dream of living in Utah, the land of Zion, was crushed when her father returned home with this “call.” She could envision a land only of desert and rattlesnakes, desolate and lonely.

Through their faithful willingness to answer the “call,” they secured heavy serviceable wagons and made preparations for the journey southward. The company left Utah January 17, 1877, under the leadership of Daniel W. Jones as presiding officer. Mary Jane was eight months old.

On March 6, 1877, they arrived at the Fort McDowell crossing on the Salt River, and crossed the river where the Lehi Ward now stands. It was here that Mary Jane took her first steps. Here they met many Indians who soon became too friendly. They always wanted to pick Mary Jane up. This worried her mother as she was afraid they might steal her. One day, as an Indian woman visited their camp, she gave the baby a little basket she had woven. This is still in the family’s possession.

They lived in tents with brush tops, drinking water from the river until a well could be dug. They took out a canal and raised crops of corn, sugar cane, and garden vegetables in abundance. They remained here for nearly six months.

President Young wrote that he would like at least a part of the company to go farther south and settle on the San Pedro River so that others would follow and in time establish colonies in Mexico. Seven families left Lehi the last of August, traveling at night on account of the intense heat and feeling less danger from the Indians. They arrived November 29, 1877, and established a settlement near what is now called St. David.[27] They camped in tents on the west side of the river close to where the Apache Power Plant now stands. They planted gardens and got water from the springs nearby. When Mary Jane was old enough to be weaned, all the milk they gave her was goats’ milk, which she did not relish. A man living near, who had lots of goats, gave them goat meat to eat, but he was thought to be very cruel as he would throw the goats from one pen to another.

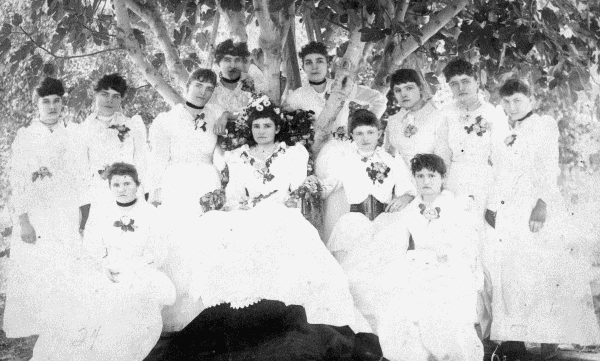

Mary Jane McRae, soon to be McGuire, c. 1980. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Mary Jane McRae, soon to be McGuire, c. 1980. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

A rock fort was built where they lived for protection against the Apache Indians. Later her father built a two-room adobe house, where they homesteaded for a number of years.

At the age of three, Mary Jane made her first public appearance and was a great lover of poetry all her life. She was called to recite for all social gatherings and could give appropriate readings for any occasion. It should be remembered that at this time there were no pianos, no radios or television, and the only means of entertainment was to use their own talents. As she and her sister Annie were the only girls in the family, they had to spend nearly all their time helping their mother with the household duties, so consequently had to commit their poetry to memory while performing these duties.

One day, while all of the older members of the family were attending a meeting at the fort, her mother sent Mary Jane for her father as she was about to give birth to a child. It seemed a long half-mile to a child of less then six years of age, who had to go through a field of sagebrush and mesquite, never knowing at what moment an Indian might attack her. This baby was named Parley Taylor, “Parley” after Parley P. Pratt and “Taylor” for his mother’s maiden name.

On May 3, 1887, at the age of eleven and while she was at school, there was an earthquake. It was at recess time, and most of the children were playing on the east side of the building. The whole front of the building fell, and many cracks were made all the way through, so it was unsafe for school to be held.[28] No one was injured, but all of them certainly had a terrible fright. Mary Jane remembered this incident all her life.

In November of 1888, when she was twelve years of age, the mother took her as baby tender on a trip to her old home in Utah to visit relatives she had not seen for twelve years. Milton was the baby, and her brother Charles was not very well. This was really a thrill, as it was her first train ride. They had to take a feather bed and bedding, and also a basket of food to last for the four-day journey. They visited there until the last of March. One of her fond memories of this visit was the apple cider and cheese which they had at the home of her grandmother. One day her brother Charles, when addressing her, called her “Mamie,” which was her nickname. Her grandmother scolded her saying, “Don’t you let them call you ‘Mamie,’ it’s a mean, nasty, ugly name.” Regardless of this experience, she was known by this name all her life.

When a young girl, she loved to dance, and their home was the center of all entertainment as it was the largest in the valley. She often told of rolling up the handmade carpet and sweeping out the straw that was used for padding. Young and old alike would promenade and square dance to the music of the fiddle of Jim Christensen. After the dances were over, fresh straw had to be put down on the floor and the carpet tacked back in place again. When she was seventeen, her father decided to move to the Gila Valley in order to give his children better advantages in school. They arrived in Safford on July 20, 1893, and stayed there until December, then moved farther down the river to the town of Thatcher. A home was built, and the children started to school. Mary Jane attended the Gila Academy in Thatcher, where she took a teaching course and also taught classes. She was respected and honored by her students and adopted a love for her teachers, [Emil] Maeser and John F. Nash.[29] At this time her mother became very ill as she had been in poor health for a long time, so Mary Jane had a great responsibility with teaching and assuming all the household duties.

She was a faithful Church worker and was well loved as a YLMIA president. It was while directing a play for the Mutual that she met her husband to be, John Sidney McGuire. After a short courtship, he left for the southern states on a mission. They corresponded during this time, and after his return they were married, November 28, 1900. They made their wedding cake together, she adding the ingredients and he doing the stirring, which took two days to prepare and bake. After the ceremony, she discarded her wedding dress for a house dress and apron, as she still had the responsibility of her mother’s care, which she assumed until her mother’s death April 19, 1901. They continued living in her father’s house until January of 1902, having the care of her father and younger brothers.

After their first child, Clare, was born, January 26, they moved to Bisbee, where he was employed in the mines. While living there, they saw the need of an organization of the Church, so Sunday School was held in their home.

Four more children were born to them: Sidney Kilby, Florence, Louis Taylor, and Ellen. Not only did she have the responsibility of her five children but also [the children] of her brothers who came to seek employment in the mines. They lived in Bisbee and South Bisbee for ten years, then moved to Pomerene, Cochise County, Arizona, where 160 acres of land was homesteaded. Here four more children were born: Annie, Florette, David, and Mary, the latter two dying in infancy.

Few women accomplished more work both inside and out than Mary Jane. Cooking had to be done on a wood stove; washings were scrubbed on a board (using her own homemade soap) as there was no electricity in the valley at this time. Water was hauled in barrels for eight years from the neighbors a mile away, until her husband dug an artesian well. Even then the water had to be carried from the well for all household purposes. The days were never too long for her to work for the family.

Although being burdened down with the cares and duties of motherhood, she always found time to serve in her church, teaching in the various organizations and acting as counselor and president of the Relief Society for many years. In all these duties, she was always dependable and faithful in her work.

She was set apart to work among the sick, make burial clothes, and lay out the dead. Her husband, who was counselor to Bishop Robert L. McCall, had the responsibility of making the coffins as there were no mortuaries in the valley at this time.[30] She would always assist him, lining the coffins and making clothing, sitting up all night with the sick, and even at the services would be called on to speak. The small community learned to love and depend on her for her faithfulness and untiring efforts.

She underwent many of the hardships of the early pioneers, being thrifty and economizing in every way she could in feeding and clothing her family. Although her home was teeming with children of her own, she never made any other child seem unwanted. She even cared for her brother’s children after his wife passed away.[31] It was a joy for neighbor children and nieces and nephews to go to their home. Her kindness always made them feel welcome to help themselves.

Although many hardships were endured, she always managed to make the best of them, always having a cheerful outlook on life. She had many experiences to prove this. They had to go to the nearby town of Benson, three miles away, by horse and buggy to do their shopping. Just before entering the town, they had to cross the railroad tracks. One day, as she and her daughter Florence drove into town, the horses had just stepped over the tracks when the tongue dropped down, leaving the buggy stalled. A passenger train was fast approaching so she screamed for help and some men nearby, seeing their plight, grabbed the tongue of the buggy, pulling her to safety—just as the train sped by. When she returned, she laughed at this experience.

Another time, she had a money order which had to be sent off that day, so she walked the three miles to Benson hurriedly, as the post office closed at 5 p.m. She arrived at the office exhausted just as the window was closed in her face. Having known the post master for many years, she tried to appeal to him, but all in vain as he refused to send off her order. Her life was filled with similar experiences.

On June 3, 1929, the family sold their home to Walter Fenn of Pomerene and moved to Mesa, Arizona, where the children could have better advantages, and they all could work in the temple, which had recently been completed and dedicated. Mary Jane devoted the rest of her life to doing genealogical work; her interests were not only in her family but in that of her husband’s as well. Through her efforts, a great research work was done and thousands of names were cleared for temple work. She also assisted in these ordinances.

After a full life of service to her family, the Church, and her associates, she passed away January 17, 1954, in Mesa, Arizona, and was buried there. January 17 was the date that one of her great missions in life began, when they left the Great Salt Lake Valley to answer Brigham Young’s “call” to settle Arizona. Also, when her call came to leave this earth it was on her mother’s 109th birthday anniversary. Her passing was mourned by all who knew and loved her, but her life will ever remain a sweet memory and benediction.

Ellis and Boone:

When Florette McGuire and Annie McGuire McDowell wrote this sketch for their mother, they were completing work that Mamie McGuire had started. They wrote, “For many years our Mother, . . . assisted by our sister Florence McGuire Naegle, gathered genealogical data concerning the McRae family and ancestry to use this information as a basis for a family book and preserve these records for future generations. However, before the book could be completed, Mother was called on to a greater Mission. In compliance with her request, we have finally completed her ‘project.’” The subtitle of their book was “A Genealogical and Temple Record of the Ancestry and Descendants of Joseph McRae and Maria Taylor and Augusta Matilda Erickson.”[32]

McGuire and McDowell mentioned that their mother memorized poetry while completing housework as a child and said she “was a great lover of poetry all her life.” They included a poem recited by their mother at age three and another recited at age five. Poetry was also interspersed throughout the book; some poems were written by family members, other poems were favorites, and others were poems that McGuire and McDowell thought described the family members.

Finally, a story about baby Mamie and the family dog was told in the sketch for Joseph McRae as follows: “Our family owned a wonderful dog. He constituted himself guardian of our baby sister, ‘Mamie’ Mary Jane. He watched her with all the solicitude of a Mother and if she strayed away he was her constant companion. Anyone could take the baby in their arms, but if she cried, his growl warned them to put the child down, and they did it quickly.”[33]

Sophia DeLaMare McLaws

Lorna Cummins[34]

Maiden Name: Sophia DeLaMare

Birth: August 10, 1857; Tooele, Tooele Co., Utah

Parents: Philip DeLaMare and Mary Chevalier

Marriage: John McLaws Jr.; December 27, 1875

Children: John William (1876), Joanna (1877), Francis “Frank” (1880), Mary Alice (1882), Walter (1883), Agnes Estella (1885), Robert (1887), Philip Delmar (1889), Jennie (1891), Ruby Elizabeth (1894), Millie May (1895), Daniel Ross (1897), Archie Leo (1899)

Death: November 28, 1948;[35] Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

To the people of Joseph City, the history of their town had become a romantic tradition, handed down for three generations. Children listen with wide-eyed interest as their elders recite the story of the covered wagon journey and the cottonwood log stockade.

But to Mrs. Sophia McLaws, the story had a far deeper meaning. For Grandma McLaws, as the old lady is affectionately known to the townspeople, was among the pioneers whose rugged determination wrested a living from the desert and laid the foundation for the thriving village.

Sophia DeLaMare McLaws. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

Sophia DeLaMare McLaws. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

She remembers well the nine-week journey across the mountains and desert; and she recalls vividly the days and weeks and months of hardships when food was almost unobtainable. For sixty-six of her eighty-four years, she has lived in the town she helped to build, having watched her friends, one by one, quietly depart, until today she is the only living member of the little pioneer band. Those sixty-six years have been filled with service and labor for her family and her friends.

Sophia McLaws was born August 10, 1857, in Tooele, Utah, the daughter of French converts to the LDS Church. Her father was Philip DeLaMare, her mother Mary Chevalier, both from the Isle of Jersey, Channel Islands, off the French coast.

Philip DeLaMare, a man of considerable skill in marine construction work, learned of the Mormon Church through Apostle John Taylor and left his home for America, bringing with him the machinery and equipment for the first sugar factory established in Utah.[36] He established a home in Tooele City for his family, where he opened a blacksmith shop, employing his knowledge of metals and construction, and became an expert toolmaker.

At the time that Sophia was born, there was a great deal of unrest in Utah. A company of United States cavalry under the command of General Sidney Johnston was sent by President Buchanan to put down a reported Mormon uprising against the government. Having had experience with soldiers before, President Brigham Young instructed his people to evacuate their homes in the region of Salt Lake City and move to the southern part of the state. It was during their trouble and turmoil that Sophia was born. The little city of Tooele was almost completely deserted—the only women in the entire town being Mary Chevalier DeLaMare and her tiny daughter and a kindly neighbor woman who braved the danger in order to help.

Sophia was one of a large family of children, and she started early to help out with the family expenses, beginning at the age of seven to tend babies during the summer. She completed her formal schooling when she was fourteen, paying the expenses of the last two years herself by working after hours at a hotel.

In 1868, a young carpenter by the name of John McLaws of Salt Lake City came to Tooele, and was employed by Philip DeLaMare at a sawmill in Tooele, Canyon. The son of Scotch converts to the Mormon religion, John had learned his trade from his father, who helped to build the Salt Lake Temple. John himself put in many days’ work on the St. George Temple. In Tooele, he built a nice little home for Sophia DeLaMare, and they were married on December 27, 1875. They never lived in the little house though, moving at first into the sawmill where he worked. And in less than a month after they were married, they received a notice from their bishop that they were among the missionaries chosen to go to Arizona and establish a colony.

On January 23, 1876, Brigham Young called all the Arizona missionaries together at a meeting in Salt Lake City for final instructions. He told them to dispose of all their belongings—leave nothing behind which might tie them to their homes. The little house in Tooele was traded for horses and equipment to make the journey.

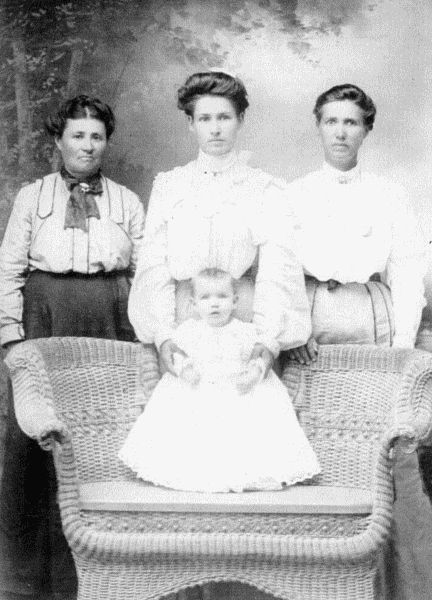

On March 23, 1938 (Founder's Day), Sophia McLaws was one of four remaining pioneers of Joseph City. From left: Mary Willie Richards (579), Emma Swenson Hansen (245), Sophia McLaws, and James E. Shelley (husband of Margaret Hunter Shelley, 632); Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

On March 23, 1938 (Founder's Day), Sophia McLaws was one of four remaining pioneers of Joseph City. From left: Mary Willie Richards (579), Emma Swenson Hansen (245), Sophia McLaws, and James E. Shelley (husband of Margaret Hunter Shelley, 632); Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

John was twenty-three, Sophia eighteen, when they began the long trip. They left Tooele February 8, 1876, joining the main company at Nephi. The company was made up of twelve wagons, drawn by horses, mules, and some oxen. There were few families, the group being mostly young men without wives. The few families had very small children.

The journey was long and hard. At the Panguitch Divide, they encountered snowdrifts six feet deep, and the men had to shovel a road for the wagons all the way across the divide. In the Buckskin Mountains the snow had changed to mud. For miles Sophia drove the team while her husband shoveled mud from the wheels of the wagon. The little party spent five days traveling the distance of fifteen miles between Kanab and House Rock Spring.[37] At Lee’s Ferry they crossed the Colorado, swimming the stock while the wagons crossed on the boat.

After a few more weeks of difficult travel of sandy stretches of desert and a few perilous days of mountains and cliffs, the party reached the Little Colorado. They traveled up the river for days, arriving at Sunset, the present site of Winslow. They had to build boats to ferry the wagons across the muddy water, and they spent three days in getting all the wagons across.

It was on April 13, 1876, after nine weeks of travel, that the little band reached their destination. The camp at Allen was already established, the first settlers having arrived on March 24, and it was just sundown when the wagons pulled in. The company was gathered around the community table, just beginning the evening meal, and the new comers were greeted with a lusty shout: “Come and get it folks. There’s beans in this soup, but you’ll have to pull off your shirts and dive for ’em.” The rest of the story is history—all the hardy young pioneers labored and suffered to build up a home in the desert. There were years of hardships—of near starvation; the Mormons stood many times on the banks of the treacherous river and watched the floods sweep away the products of months of labor. They watched some of their neighbors pack their scanty belongings and turn back toward Utah because the wind and the sand and the starvation were too much for them.

Grandma McLaws was there throughout the years of growth and development. She was among the women who stood in the icy river and washed wool to be carded and spun into clothing for their families. She was among the women who made the long trip to the dairy at Mormon Lake and made butter and cheese to feed the growing children at home. Hers was the first baby born in the new settlement; and hers were the tender hands that helped many a young mother through the pain and terror of childbirth. She stood firmly beside her husband through the years, helping him in his various duties as postmaster, school teacher, Sunday School superintendent, and carpenter. She danced many a night on the dirt floor of the fort and the rough board floor of the school house. And during all the years of hardship and struggle, pain, and happiness, she raised her own family, seven boys and six girls.

As the years went by, John and Sophia McLaws watched their old friends and neighbors pass on, one by one, a man’s wife or a woman’s husband, until they were the only couple left. Then in 1935, John was called, and Sophia was left alone. Now [1941] at eighty-four, she is the only living member of the original pioneer band who came from Utah sixty-six years ago to establish a colony. She lives still in the home her husband built for her, still active and industrious. And the days of long ago are still vivid in her memory, as she tells the stories of the pioneer days to her grandchildren and her great-grandchildren.

She lived until 1948, dying November 28, 1948, at the age of ninety-one years, three months, and eighteen days. After Daddy died March 7, 1935, Mother lived very quietly in the home he built for her in 1883. She suffered a lot with arthritis in her hands and arms. She took care of the traveling public for forty-five years, and wherever there was sickness and death, she was called. Daddy made all the caskets for sixty years, and when he died, his son and son-in-law made the casket for him. She had 387 descendants at the time of her death.

Ellis and Boone:

Sophia McLaws was an important part of early Joseph City. Alice Smith Hansen wrote, “Mrs. John McLaws (Sophia) had a natural gift for nursing and a ‘know how’ of what to do when accidents occurred. She assisted at the bedside of the sick and helped in the care of new born infants. She had a special skill of knowing how to handle patients with ease and the distressed felt comfort and strength from her soothing hands. Her original and home-concocted remedies became famous, for everyone felt that ‘Sister McLaw’s’ [sic] salve or pills would surely bring the desired results.”[38]

This story from granddaughter Mary Pickett also helps understand the early settlement of Joseph City. She wrote:

Scarcity of food was every present in the first years and at one time wheat was the only thing available. Sophia McLaws worked in a hotel as a girl and was well trained in serving the public. From the very first her home was frequented by many travelers. Many of the Church Authorities who visited the Colonies in the early years were served in the McLaws home. At one time two of the Church Officials came to their home for something to eat and a bed for the night. Sophia always liked to serve well and she went out to the wood-pile for kindling to build a fire. When out of sight of the home she sat on some wood and cried bitter tears because she had nothing but wheat to give them. The crying over, she gathered her kindling wood, went in, built the fire, ground the wheat on a small hand mill, made cereal of it and placed it before her guests who were grateful for what was the best she had to give.[39]

But Alice Hansen also told a more lighthearted story from Sophie McLaws. When the first colonists came to the Little Colorado River, there were a few unmarried men with them. Hansen wrote, “With the united effort of every man, the first season’s crops had been gathered. It was then considered an opportune time for some of the leaders to go back to Utah and in the following spring to return with their families who had not yet come to Arizona. Joseph McMurrin was homesick, but because he had no wife or family in the homeland, he was left to endure the winter in the lonely environs of a beginning settlement.[40] He made many mournful remarks about his unfortunate state because he was a bachelor without a wife.”[41]

Sophie McLaws decided to cure McMurrin of complaining. She enlisted the other young ladies of the fort and made McMurrin a helpmeet.

Evening came and the ladies could hardly wait for Joe to announce he was tired and would be going to bed. Everyone was unexplainably quiet when the sound of a great crash coming from McMurrin’s room indicated that his bed had fallen. Rushing in with no shoes on and hair disheveled, Joe McMurrin was hugging his dummy wife. “Why don’t you make me a gal with more warmth,” he complained to Sophia whom he knew had given great support to the project of proving him with a needed wife. [Sophia replied,] “You wouldn’t want us to use your rib would you Joe? That would take us too long.”

“Here!” yelled Joe as he proceeded to take his manufactured help-mate to pieces, “Take your old dress Polly Whipple. You need it worse than I,” and holding up a petticoat . . . announced that he could not designate the owner of this.

“It’s Sophy’s,” piped up Joe McLaws.

“And these sheets are so white, I know they haven’t been washed in river water.”

“Nope,” confessed Maggie Shelly. “I’ve been keeping them nice for this occasion.”

“And these,” called out Joe holding up suggestive white squares, “must belong”—there was a pause, and the diapers were merrily flung at Joe Morris, another bachelor in the fort.

When Joseph McMurrin became one of the Seven Presidents of Seventy, he frequently represented the General Authorities in visits to Snowflake Stake. Needless to say, these occasions provided a time of happy reunion and merry reminiscing with his early and loyal friends in St. Joseph.[42]

Mary Ann Smith McNeil

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview, and Anna Thompson[43]

Maiden Name: Mary Ann Smith

Birth: July 2, 1853; Manchester, England

Parents: William Smith and Mary Hibbert

Marriage: John Corlett McNeil; September 12, 1868

Children: Sarah Alice (1870), Daniel (1873), Ephraim S. (1874), Lillis (1876), Hannah S. (1878), Angus Smith (1879), Benjamin S. (1880), Althera (1883), James Hibbert (1885), Jesse Smith (1887), Annie Frances (1890), Willie Smith (1892), Frederick Smith (1893), Don Carlos (1896)

Death: May 30, 1944; Show Low, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Show Low, Navajo Co., Arizona

From a comfortable home in Manchester, England, to a dugout in Utah is quite a contrast, yet it was experienced by Mary Ann Smith, the subject of this sketch.

Born July 2, 1853, the daughter of William and Mary Hibbert Smith immigrated to America in 1856 on the ship Wellfleet.[44] The family made its way to Missouri, where they remained for a while, outfitting for the west. They obtained a team of oxen and a wagon and made their way to Salt Lake City, Utah, with a group of other pioneers led by Ansil P. Harmon, landing there when Mary Ann was ten years old.[45] Because they had only one wagon and it contained all the family possessions, Mary Ann had to walk most of the way. When she was very tired, she would ride on the long reach pole that stuck out behind the wagon. This was far from comfortable and not very safe.

When they settled down it was in Bountiful, Davis County, Utah, where at the age of fifteen Mary Ann was married to John McNeil in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.[46] Their first home was a one-room dugout, and here was born their first child, Sarah Alice. They continued to live in Bountiful until November 18, 1878, when they started for Arizona to make a new home. Of the trek down Mary Ann says:

It was a long hard journey. I was sick most of the time because of the cold weather. I was very sad because I had to leave my beloved parents and relatives to come to a country that was unsettled, without a home or friends and where the [Native Americans] roamed at will.

By this time I had five children to care for. My baby was only nine months old and was sick most of the time. She couldn’t stand the jolting of the wagon, so the children and I took turns walking and carrying her in our arms most of the way. Our outfit consisted of a wagon and a span of horses in the lead, then a yoke of milk cows, and the wheelers were a span of mules.[47] We put the milk cows in the team as we had no one to drive them.

Traveling by team was slow and we hadn’t gone far when it began to snow. When we got to the canyon eighteen miles from Kanab, Utah, my husband had to leave us and go on to that town for help, as our poor team was given out and we could go no farther. There was eighteen inches of snow on the ground and bitter cold. I am sure we would have all frozen to death before he got back had not two men happened along traveling our way. At first I was afraid of them as they asked us a lot of questions, but when they learned of our plight, they brought wood to make a campfire and camped close to our wagon that night. They went on next morning and wanted to take the children and me with them to Kanab, but all we had was in that wagon and I did not want to leave it. My husband had left me there and there I would remain until he came for me, which he did that night, bringing with him Joseph Noble and a team belonging to John H. Standifird. On Christmas day we reached Kanab, glad to be alive. We lived that winter in Mr. Standifird’s cellar, and next spring rented a house of Jacob Hamblin who was leaving for Arizona. We stayed here until fall raising a good garden and lots of apples. When the crop was gathered we started again for Arizona. People told us that apples would bring a good price so we left our cook stove and many other things there that we might load our wagon with apples, but long before we reached our destination they were all frozen and we got nothing for them. We had to cook over a campfire for a year before John went back to Kanab and got our stove.

Sometime in December we arrived at what they called Walker, now Taylor, three miles above Snowflake. We stayed a week with James Pearce, then went to a place on Silver Creek known as Solomon’s Ranch. Here Mr. McNeil built a fireplace and chimney of rock near the side of a hill and then stretched a tent over it and there we lived until March of the next year. Mr. Standifird had previously moved to Arizona and lived about a quarter of a mile south of us. We had to go to his place to grind corn on his coffee mill for bread as we had none of our own. My husband was a shoemaker and would take his tools and go to Snowflake and Taylor and repair shoes, taking anything he could use in exchange but the people there were little better off than ourselves. One night we had only enough food in the house for one meal, so I coaxed the children to leave it for breakfast. That night we went to bed without supper but in the night John came home with a little corn that he had traded dried apples for. We were entirely without soap at one time and no grease to make any. We didn’t know what to do but a fat coyote had been pestering around so John set a trap for it. With the grease I got out of the coyote and lye made of corn cobs or wood ashes I made some soap. It did not harden like soap made from beef tallow but it was better than none.

One of Mrs. McNeil’s neighbors tells how neatly she always dressed her children. The little girls’ dresses always had to be laundered just so and though “boughten starch” was out of the question and the McNeils didn’t have flour for bread, Mrs. McNeil would take a bowl of cornmeal to a neighbor and trade it for flour to make starch with which to starch their dresses and aprons.

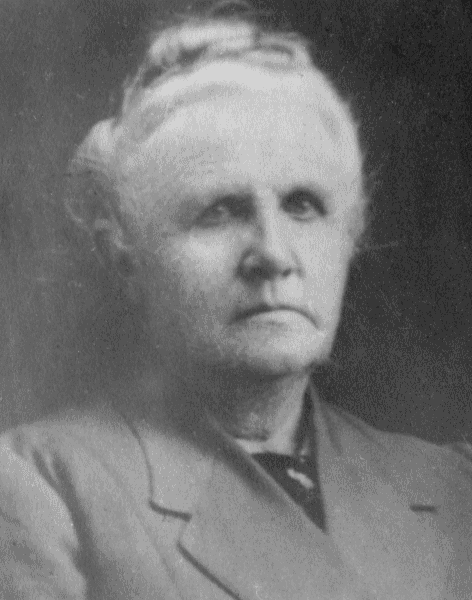

Mary Ann Smith McNeil. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Nikolaus Collection, Show Low Historical Society Museum.

Mary Ann Smith McNeil. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Nikolaus Collection, Show Low Historical Society Museum.

Continuing with Mrs. McNeil’s own story:

That winter we lost our best horse. He starved to death. There was no feed on the range and we had no money to buy feed. Then in the spring we moved over to a place called Forest Dale on the Indian Reservation. We lived with the Indians all summer. We bought some corn at 5¢ a pound. We had to shuck, shell, and grind it on a hand mill. We thought that was an awful high price for musty, mildewed corn. The smell of it made me so sick while it was baking, sometimes I wondered how I lived through the summer. All we had to eat was that musty corn bread and molasses with a little milk. All the clothes my boys had to wear was just a shirt, no pants, and the girls a little slip.

After the musty corn was gone, all we had to eat was what we had raised in the garden and that was mostly green corn. Yes! It was green corn for breakfast, corn for dinner, and corn for supper with a little dutch cheese (or cottage cheese) for a change. When the corn got hard enough to grate, John made me a grater out of an old tin pan by driving nails from the inside out of the bottom of the pan. So we all had a grating good time to keep ourselves in bread and mush.

The Indian Chief, Petone, became angry at the Thanes and some of the other families. He said, “They lie, no good.” He told John that he was going to scare them out by telling them that Geronimo was coming to fight. But he told John to sit down—“He no lie, he a good man, sit down, Indian no hurt.” So he stayed. Everyone else left. I wanted to go but John wasn’t afraid of the Indians, so he stayed and took care of his crop, also the crops of the other people, then in the fall the men came back to gather theirs.

The winter of 1880 we moved from Forest Dale to Show Low. There another baby was born to me. It took John nearly all winter to move his corn out of Forest Dale, but that was what we depended on for bread, so we had to have it hauled out. Many times I got so hungry for flour bread that I felt like I would give all I owned for a cup of tea and a piece of flour bread.

One day my son Dan and I hitched up our team and drove out to Robert Scott’s sheep camp to get some supplies from a little supply store that he kept for his sheep men. Mr. Scott fixed us some dinner consisting of hot biscuits, fried mutton, and tea. Just what I had been longing for and was a feast I never will forget.

I did lots of sewing for the [Indian women]. Their skirts had ten widths of material in each one, besides trimming by the yards. I had to use my own thread. I used up two boxes that I had brought from Utah. When it was all gone I could not sew anymore and I was glad of it for they pestered me continually to sew for them. One day an Indian man came and asked me to make him a shirt. I told him I was sick and couldn’t. He kept coaxing me so I told him I had no thread. He got awful angry and called me names he had learned from the soldiers at Fort Apache, so John told me I had better make him a shirt. The summer of 1880 the Indians gave us a war scare. It was about the middle of August.

Mr. McNeil and the Indians were great friends. He was never afraid of them but the children and I were. He and Moses Cluff helped the Forest Dale Indians build a fort. It was a hollow place made in the top of a hill. They lowered barrels down into the fort, where they were hiding their food, [women,] and papooses.

The San Carlos Indians came up to fight the Apaches. There was three or four hundred of them, and they were painted and wearing skeins of red yarn around their heads. They turned their horses loose in our corn field. John left us and the children while he went to take care of the corn and fix up the fences. We were nearly scared to death. The Indians came up to the house. We had a watermelon patch in front of the house. They came and asked me for some. I traded a melon for three skeins of yarn. They soon stopped wanting to trade and took to helping themselves not only to the melons but to the things I had in the house. They took my butcher knife, cups and all my soap and everything else they saw that they wanted. The children clung to my skirt and we were all trembling with fear. Oh, how I prayed for the Lord to spare our lives. Soon they began to leave. John came back and said there had been a dispatch sent by Corydon Cooley to Fort Apache for help and the officers and soldiers came and settled the trouble.[48] The San Carlos Indians went back. They had no fight but it was an awful scare we got.

After we moved to Show Low, Geronimo and his followers gave the people another scare. The people got together in a fort so they could fight if they had to. John wasn’t afraid so wouldn’t go into the fort. So we moved down to the Lone Pine Crossing. Old Father Reidhead and two or three more families lived there. We stayed there all winter. We were hungry most of the time as food was scarce. One day John caught a beaver in the creek and we ate that and enjoyed it.

In the spring of 1881 we moved to a place three miles farther south of Lone Pine. John built a log house and we lived there until 1899. The ruins of the old house are still to be seen from the new state highway 60. While there, five more children were born to me making me the mother of fourteen children.

In the year 1900, we moved to Old Mexico. We stayed there for five years.[49] My husband died there in 1909. I came back to Arizona and homesteaded a nice piece of land one and a half miles from Show Low and built a quite comfortable home on it. I had to walk all the way whenever I wanted to come to town. Now I was lonely, unhappy, and not strong enough to walk to town any longer. My son Eph bought a lot in Show Low on which was a log cabin so I would be near enough to walk to the post office, visit with neighbors, and attend church services and recreational programs. We lived in the cabin for a number of years, raised fine gardens, and sold vegetables and strawberries. Beautiful flowers adorned the yard.

Thus ends the story as told by Mary Ann McNeil. The following part is written by her daughter Anna Thompson:

Ephraim built a new and larger house among the flowers and trees near the cabin where she spent the last years of her life. She said, “This is the best home I have ever had.”

A party held the day she was eighty-three years old brought 73 of her 178 descendants together. In the group were nine sons and daughters who met for the first time in twenty years. At another party held on her ninetieth birthday, she and two sons step danced.[50] In the spring of 1937, she became seriously ill with pneumonia. Her three daughters, Lillias, Hannah, and Annie, came to her home and nursed her back to health. Mrs. McNeil had little school training. However, she had a fine mind and sought learning through extensive reading, observation of nature, and the people whom she met. Therefore, she became a fairly well educated woman and informative conversationalist. “Grandma” McNeil, as she was known in her later years to many relatives and friends, was a lover of beauty. From her flower garden, she adorned the church pulpit each Sunday, and she cheered the sick, aged, and homebound with beautiful yards of crochet, knit, hairpin, and tatted lace. Her home displayed doilies, cushions, pillows, rugs, spreads, and quilts made by her hands, for they were never idle. She gave and sold many handmade articles to friends and neighbors. During her life, she devoted much time to church work. She was president of the Relief Society for years, and when the people lived on ranches, she traveled miles on horseback to attend meetings and aid the poor and distressed. She was secretary of the first Society in this area, 1883. She was secretary of the YLMIA in 1887. In 1893, the General Board of Education of the Church issued to Mary Ann McNeil a license as Instructor of Religion Class in the Show Low Ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This license was signed by Pres. Wilford Woodruff and Dr. Karl G. Maeser. This was a distinct honor which came to her because of her knowledge of the gospel, her loyalty to its teachings, and her selfless service to her fellowmen.

During the time she lived in the log cabin, she was again chosen as theology class leader, also a faithful visiting teacher. Interested in genealogy, she spent considerable means for research; she spent two winters in the Mesa Temple doing vicarious work for her kindred dead.

During World War II, magazines and newspapers carried articles stating that the large number of descendants of Mary Ann McNeil in the armed services was some kind of a record. In uniform were seven grandsons, eighteen great-grandsons, and one great-grandson-in-law. Three great-grandsons and the husband of a great-granddaughter gave their lives in defense of their country.

When her long, active life came to an end, sadness spread over the countryside. She passed away May 30, 1944, in the beautiful home her son Ephraim built for her.

Ellis and Boone:

The following note has been posted on ancestry.com: “Mary Ann Smith (McNeil), Daughter of William Smith and Mary (Hibbert) Smith and third wife of John Corlett McNeil, kept extensive diaries. These have been gathered together, with comments in italics, by her grandson Peter McDonald. . . . This account begins with the diary and writings of Mary Ann Smith as she and John McNeil leave Utah for a mission in Arizona. It then continues when she returns from Arizona to Salt Lake City for a visit (in 1898), and then continues with her life in Arizona and then moving to Mexico in 1899. The diaries end in Mexico in late 1901.”[51] It may be that some of these diaries helped Mary Ann McNeil remember events as she talked with RFC for the FWP interview.

When Roberta Flake Clayton submitted the FWP sketch for Mary Ann Smith McNeil in the 1930s, the sketch ended with the following description of Mary Ann Smith McNeil:

“Mrs. McNeil is a remarkable woman, always pleasant and good-natured and has never lost her love for fun. She still retains her bright sparkling brown eyes, her good looks and her grace. At the annual Old Folks Reunion [in Phoenix, sometimes called the Heard Reunion] she always delights the audience with her step-dancing and the occasion would not be complete without her gracious presence.”[52]

Maria Taylor McRae

Florette McGuire and Annie McGuire McDowell[53]

Maiden Name: Maria Taylor[54]

Birth: January 17, 1845; Spilsby, Lincolnshire, England

Parents: George Edward Grove Taylor and Ann Wicks

Marriage: Joseph McRae; March 3, 1862[55]

Children: Eunice Ann (1863), Joseph Alexander (1865), John Kenneth (1867), George Edwin (1870), Annie Maria (1873), Mary Jane (1876), Nymphus Charles (1879), Parley Taylor (1882), Orson Pratt (1884), Milton (1888)

Death: April 19, 1901; Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Maria Taylor was born in Spillsby, Lincolnshire, England, on January 17, 1845. She was the daughter of George Edward Grove Taylor and Ann Wicks. She had one older brother, Joseph Edward, and two older sisters, Margaret Ann and Martha.

When Maria was seven years of age, some elders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were sent from America to preach the gospel to the people of England. The family gladly accepted their message, and Maria could hardly wait for her eighth birthday so she could be baptized. Her father and brother were appointed as local missionaries and made [brought] many converts into the Church.

Maria only went to school a few weeks in England, where about all they taught was sewing, having to count the threads of the cloth between each stitch.[56] She was well rewarded for her patience, as later she became a good seamstress. She was the mother of seven children before she had a sewing machine.

The family wished to go to America, but as they did not have the money for all to go, they thought it best to send their son, Joseph. He arrived in Salt Lake City in 1852, obtained employment at different jobs.[57] Later he became one of the pioneer undertakers and built the first coffin factory west of the Mississippi river.

As soon as he could save enough money, it was sent to his mother so that she and his two younger sisters, Martha and Maria, could pay for their voyage to the United States.[58]

They were ten weeks and three days crossing the ocean. They arrived at St. Louis and remained there a year. Each went to different homes to work. The mother did nursing, and the girls took care of children and washed dishes to pay for their board and room. Maria was small for her age and had to stand on a box to wash the dishes and mix bread.

Maria Taylor McRae. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Maria Taylor McRae. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

With the help of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, they started for Salt Lake City, a thousand miles away.[59] They shared a wagon with another family, and as her mother was sick most of the time and her sister not very strong, Maria had to walk most of the way.[60]

As she trudged along over the rough country day after day, Maria became very discouraged. One day she went and sat down under a tree and let the wagons go on by. Soon she heard a noise and, looking up, saw a large Indian standing nearby. She arose and ran as fast as she could, the Indian following her, but he didn’t try to harm her. When they were near the wagons, he disappeared into the bushes. This taught her a lesson, and after that she stayed near the others.

After suffering many hardships, they arrived in Utah and stayed at the home of her brother, Joseph, a while. Then again, they each went to different homes to work. Maria was fortunate, living in the homes of cultured people, [like] the Whitneys, where she helped to care for Orson F. Whitney as a baby.[61] She would take him for walks up City Creek Canyon. He has said his first recollection was the wild roses that grew there. She later lived in the home of Emmeline B. Wells, editor of the Woman’s Exponent, later called the Relief Society Magazine.[62] Sister Wells was very kind to her, encouraging her to read, and related many wonderful experiences in her life and of the Church. Maria became so attached to the daughter, Annie, that she later named her own daughter after her.

As the girls grew older, they earned fifty cents a week and paid for their clothing. They had three dresses a year, two made of unbleached muslin, which they dyed with the bark of trees or plants, and one wool dress made in the fall, for church and social occasions.

Maria was about four feet, five inches tall, had grey eyes and dark auburn hair, with a permanent wave that could never be combed out, and always kept a clear English complexion which never freckled in spite of dust and heat of traveling.

On March, 3, 1862, she married Joseph McRae, son of Alexander McRae, who was in Liberty Jail with the Prophet. Their lives were mostly spent in pioneering, living the first years of their married life in Salt Lake, where four children were born: Eunice Ann, dying in infancy, Joseph Alexander, John Kenneth, and George Edwin. As Maria’s brother, Joseph, had some farming land in Wasatch County, he offered the land to Joseph and Maria to run on shares, so the family moved to the town of Charleston, where two daughters, Annie Maria and Mary Jane, were born. It was here they built their first home.

As their home was about completed, Joseph had gone into Salt Lake to conference to buy more lumber, but returned with a “call” from President Brigham Young to go to Arizona to help settle some of the wastelands there.

It can well be imagined the feeling of the family, especially Maria, when the father arrived home and told of the new plans. New adventure was exciting for boys, who no doubt were dreaming of fighting the Indians, but for Maria, always pioneering, always wanting a home where some of the comforts of life could be had for her growing family, this must have come as quite a blow. A home had been so near before her husband left, and now at his return the plans had been changed so completely. However, never doubting the divinity of the call, never shirking her duty, she went quietly about getting their possessions ready for the long trip into the “land of privation and hardships.”

Taking their lives in their hands, but with great faith in their leaders, they sold their home and left Charleston with their five children. Joseph and the boys started in November with the teams, and Maria and the girls went by train to Minersville, Utah, to the home of her sister, Margaret Goodman. Her husband and boys met them, and they spent Christmas together. They went on to St. George and were there for the dedication of the temple in January.[63]

They formed a company here at St. George under the leadership of Daniel W. Jones, and with two teams and wagons, loaded with what food and essentials they might need in an unknown country, they set out.[64] Arizona at that time seemed to be mostly inhabited by Indians who were committing many depredations.

When they reached the Colorado River, Joseph had to sell a wagon, and Maria gave up her valuable flat irons and other useful articles to pay the ferry man for helping the company cross the river. They now had to crowd in one wagon till they reached the Salt River and camped where Lehi now is. They went to work and took out a canal, planted gardens, and lived in tents.

As they had received a letter from President Young asking that at least a part of the company go farther south and settle on the San Pedro, they with six other families left Lehi the last of August. The privations and hardships of this journey are explained in the history of her husband.

On arriving at the San Pedro River near what is now called St. David, they again camped in tents. For these refined and delicate mothers, sick and sad, deprived of the comforts of home, cooking over fires in the open when the wind filled their eyes with fire and dust, going to bed and getting up unkempt and unwashed, their children deprived of the little niceties of civilization made them very discouraged and disheartened.

In a letter from Maria to her mother, here is just a little of the heartache:

San Pedro River, Arizona

2 February 1879

My dear mother:

This is Sunday afternoon and we have no meeting so I thought I could not occupy my time better than to answer your very welcome letter. We were very glad to hear from you and that you were all well, as it found all of us pretty well. The children have the chills sometimes. I have not had but one hard chill since we have been here. We do not know what we are going to do yet about where we shall live. President Taylor writes he should not like to have the settlement broken up on the San Pedro River. He thinks it will be more healthy farther back from the river, but it will be very expensive to take the water out. The most of the company feels like trying it another year. It is nearly time we were settled down somewhere. When I read about what the sisters are doing in Utah, I feel as though we were not doing much good, but I suppose it is all necessary for the forwarding of the work.

Dear Mother, I can realize how you loved the Society of Saints, for I long for the time to come when there will be some good Latter-day Saints come here to live. Do not think there is none here, but when you mingle with people every day, you begin to know one another so well that there is nothing new; but when you are deprived of a blessing, you know how to appreciate them when you get a change, mother.

You wanted me to write a long letter, but we have nothing particular to write about. I have plenty of hard work as usual. We have two boarders, besides our own family, and living in a tent is not as convenient as a house, but I want to try and get a few things that we need. We are surrounded by gentiles and they are a rough set. They have nearly all been to Utah and have drifted down here.

Tomorrow is Annie’s birthday. She is very large for her age. It does not look like it did in Charleston six years ago. The ground is dry and dusty, and very warm in the middle of the day but very cold at night. This is a good climate if it was only healthy.

Joseph and the children send their love to you. I must stop and get supper. Give my love to all.

From your loving daughter,

(signed) Maria McRae

P.S. We live 38 miles from the post office, so I do not know when I shall get a chance to send this.

After living here for sometime, they managed to build a fort to protect them from the Apache Indians. They were never molested, as Joseph said, “We were not called down here to be killed by Indians,” but they had many scares. After they were settled in the fort, everyone became ill with chills and fever except Joseph. Maria had a settled fever all summer, which they called “malaria.” At times the sick had to wait on the sick. In October, while all were sick with these chills, Apostle Erastus Snow and others made them a visit from Salt Lake City. He administered to the sick and promised them that this river would yet be settled with Saints. Maria believed this promise and hoped to live to see it fulfilled. As nearly all were sick in bed, she must have had great faith.

It was truly a blessing to the new settlers when the Lord guided Bro. John W. Campbell to join with the Saints on the San Pedro. Great was the relief and many of the problems solved when he gave the Saints work on his sawmill and food from his store.

Joseph and Maria took their family and moved to the mountains to work. He was happy to get the money that they sorely needed at this time and was in hopes that a change of climate might improve her health, getting away from the intense heat and the diseased water, as at that time it was not really known what was causing the “malaria.”

In Miller Canyon, Joseph built a large one-room house out of new lumber, thinking to have a nice comfortable room when the baby was born. Shakes were put on the roof instead of shingles. As the lumber had not been seasoned, the boards shrank. So, on September 20 as the rain poured down outside, their son Charles was born, being the first white child born in Cochise County. Pans and buckets were placed over the bed to keep Maria dry.

Sometime later they came back to the fort and helped settle the valley, taking out a canal, freighting to Tombstone (which was discovered in 1878), and also to Bisbee later. Here a home was built, and three more sons were born: Parley Taylor, Orson Pratt, and Milton.

Maria taught the first school here in St. David. This was in 1878 and 1879. She would call in the neighbors’ children and teach them along with her own. She didn’t want her children to grow up in ignorance. It is said that she was the first teacher in Cochise County. She, with Susan Curtis, established a school in her home.

The McRae home was the largest in the community. They held lots of entertainment there and always had a group in their home.

One night Maria had a dream in which she saw canals along the foothills above the town, and everything was green and pretty. Maybe, if Charleston Dam is ever completed, this may come true. She loved St. David very dearly and even after moving to the Gila Valley, she wanted to return here.