L

Roberta Flake Clayton, Louise Larson Comish, Lucinda Helen Leavitt Randall, and Lora Lisonbee Hancock, "L," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 377-416.

Harriet Cornelia Clawson Lamb

Roberta Flake Clayton[1]

Maiden Name: Harriet Cornelia Clawson

Birth: February 11, 1840; Buffalo, Erie Co., New York

Parents: Zephaniah Clawson and Catherine Reese

Marriage: Joseph Smith Lamb;[2] September 4, 1857

Children: Joseph Smith (1858), Catherine Reese (1860), Victor Emanuel (1862), Louis Edwin (1864), Fredric William (1865), Helen Lillian (1867), Sydney Beatie (1870), Mark Vernor (1873), Royal Amos (1875), Leonard (1878), Ruth Katrinka (1880), Harriet (1882), Mae (1884)

Death: July 20, 1911; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Harriet Cornelia came into this world shortly after her father, Zephaniah Clawson, left it. She was the youngest of four children—two boys and two girls, and her widowed mother joined the Church the same year Harriet was born. When the Church called for all the faithful to move to Nauvoo, the Clawsons did so, and this young mother also later crossed the plains with her small children.[3]

When Harriet grew to young womanhood, she became the wife of Joseph Smith Lamb, and they were the parents of thirteen children. While living in Salt Lake City, Harriet helped her brother Hiram Bradley Clawson with costumes for plays presented in the Salt Lake Theater.[4]

Joseph was associated with some other young men as members of a dance band. One night Harriet went somewhere, leaving him home to mind the baby. While she was gone, the band members came for him unexpectedly, saying they were engaged to play for a dance. He protested that he had to stay with the baby, but they overruled his objections, picked up “baby, cradle, and all,” and away they went to the dance. Harriet was very bewildered upon returning a little while later to find not only her husband missing, but the baby and cradle, too!

The family later moved to Farmington, and from there to Monroe, which was then in the process of being settled, living at first in the fort with the other settlers.

In about two years, danger from the Indians lessened enough that the people could leave the fort and begin to build houses on the city lots which had been laid out. Joseph and Harriet, with their children’s help, built an adobe house on a lot on the east side of town, later taking up a homestead on the west side. Joseph worked as a cooper, making trips into the mountains with his older sons to cut logs for material to make staves for barrels, tubs, churns, and buckets. The boys peddled the finished articles around the town to help keep the family.

It became Harriet’s responsibility to care for her family in the fort at Monroe for two years while Indian troubles threatened the new community there. It must have been a relief to all when it was judged safe to move onto the city lots. Harriet and the children helped Joseph make adobes for their new home.

After living in Monroe for nine years, they received a letter from David P. Kimball, telling of the Mormon settlement in Mesa, Arizona, and of the natural advantages of that country.[5] So after talking it over, they decided that it would be a good place to go with their now large family of children. Gathering together an outfit consisting of one wagon drawn by four horses and another wagon drawn by a team of mules, they left for Arizona, about October 15, 1880.

Joseph Smith and Harriet Cornelia Clawson Lamb. Photo courtesy of Phillip Stradling.

Joseph Smith and Harriet Cornelia Clawson Lamb. Photo courtesy of Phillip Stradling.

Traveling up the Sevier River through Marysville, Panguitch, and by Orderville, they came to Pipe Springs. It took two or three days to go over the Buckskin Mountains and on to [House] Rock Springs. Finally, they arrived at Lee’s Ferry, on the Colorado River, where they camped all night before crossing the river on the ferry boat. Next came one of the most dangerous parts of the trip, the journey up Lee’s Backbone, which was a high rocky ridge of mountain with gorges running out from either side, the ridges between them looking like ribs of a skeleton projecting out from the central ridge or “backbone.” It was hard work to drive along this part, which was just wide enough for a wagon along its top, with steep canyons dropping away on either side. It was so steep that it was necessary to block the wheels with rocks every time the horses managed to pull the wagons up another foot or two on the trail.[6] After conquering the Backbone, they traveled over sand and rocky hills.

There were eight living children in the family at this time and some of them contracted typhoid fever, becoming very ill. Joseph and Harriet were afraid their little daughter Ruth would die when they were at Rock House on the Colorado River, but she managed to survive. Harriet was a brave woman and nursed her children as best she could under the trying circumstances, with prayer and love, trying to make them as comfortable as possible while traveling in the wilderness.

They pushed on around San Francisco Peaks where Flagstaff is now located, although there was no city there at that time, just one open cattle ranch. The railroad had not yet got to this point. By that time it was November, and they traveled on to where the town of Williams now is, and then to Ash Fork. All this time the children were getting worse with the fever, and the parents thought Victor surely would die about the time they turned south through what is now called Lonesome Valley, but he, too, lived. They passed east of Prescott, down the Black Canyon, and out onto the desert north of Phoenix, arriving in Mesa the last of November. The trip from Monroe had taken six weeks. In Mesa, they were able to get butter and milk for the children and the sick ones were soon better, but some of the others then came down with typhoid fever after their arrival in Mesa, and it was February before all were well again.

Their first home in Mesa consisted of their tents pitched on the northeast corner of block eleven, on the tithing property, where they remained for about two months. Then they bought block 26 from William Crismon for a hundred dollars, selling the west half to Edward Bloomer for fifty dollars. Joseph and his sons built an adobe house on the southeast corner of their property, and another building facing Main Street, in which they opened a store, the second one started in Mesa. The latter building was later occupied by a Chinese laundry.

Joseph filed on a quarter section of land, and later selling the relinquishment for a span of mules, purchased another piece of ground and sold it for two hundred dollars, with which they bought goods to stock their store.

Harriet was blessed with an excellent sense of style and good taste in clothing. She ordered dresses from a catalog house in New York, choosing styles she felt would be becoming to various Mesa women. Almost invariably, the woman she had in mind when ordering a particular dress, would, upon entering her store, be attracted to that dress and buy it. One of her own favorite dresses was a plaid silk, which was very becoming to her, with her dark hair, blue eyes, and rosy cheeks.

Their home was made pleasant by the row of fig trees along one side of the yard, an osage hedge along the other, and cottonwood trees along the back. Apricots and plums grew in the yard, and there was a big lawn at one side, with a large porch connecting indoors and out.

Along with her many duties, Harriet also rendered church service, working in the Relief Society, and going into the homes of the sick to give aid. The socials afforded by the town in those times gave her much enjoyment, and she was very fond of reading. Her creative ability and aptness as a seamstress enabled her to make articles usually considered impossible by the average person, such as beautiful artificial strawberries, and once she made a pair of white shoes for her daughter Ruth. Her brother, Hiram B. Clawson (father of Rudger Clawson of the Council of the Twelve) came to visit her at Mesa.[7] Upon his return to Salt Lake City, he sent dolls to her little girls.

While the family lived at Goldfield, people came to their dance hall from Willow Springs. If it chanced to rain, they stayed overnight sleeping on the floor of the dance hall, in which event Harriet served as an impromptu hotel keeper of sorts.

This courageous woman was a loving mother, always doing the best she could to make an attractive home, as well as helping out with the living. In Mesa, she arranged for her girls to sell buttons and notions around town, helped her husband in his grocery store, and kept a little notion store, selling thread, buttons, candy, etc. Later, she opened the first ice cream parlor in Mesa, having three tables and a counter.[8] The milk was kept sweet by wrapping wet burlap sacks around the milk cans. It was the custom for people to come to town on Saturday nights, especially were the young people attracted by the delicious treat, which sold for twenty-five cents a dish, with crackers.

She died July 23, 1911, in Mesa, Arizona, nine years after the death of her husband. The newspaper report of her death stated, “Mrs. Lamb was a most highly respected woman and leaves as friends all who knew her.”[9]

Ellis and Boone:

The various business activities Harriet Lamb participated in while living in Arizona is impressive. She was an expert seamstress, ordered items for her husband’s general merchandise store, operated an ice cream parlor, had a notions store, and ran the dance hall at Goldfield. Gold was found in the western slopes of the Superstition Mountains in 1892 and immediately the town of Goldfield, twenty miles east of Mesa, sprang up. As with many other mining communities in Arizona, its life was short; by 1898, the ore vein had run out and Goldfield became a ghost town.[10] Sons Louis, Fred, and Roy Lamb worked in the mines at Goldfield, and Victor, Mark, and Syd ran cattle in the Superstition Mountains.

Joseph S. Lamb was an expert violinist. Often he played with Hyrum S. Phelps and Joseph Bond in Mesa, but he also had a family band. He and son Roy played the violin (and Roy sometimes played the piccolo), Fred played the guitar, and Mark the drums. The family orchestra provided the music for the dance hall at Goldfield.[11]

Emily Lanning

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Emma/

Birth: March 27, 1831; Buncombe Co., North Carolina

Parents: Joseph Lanning and Margaret Morrison

Marriage: Unknown

Children: None

Death: maybe 1900−10; maybe Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: maybe Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona[12]

No book on the lives of pioneer women of Arizona would be complete without a chapter on the life of “Aunt” Emily Lanning.

It cannot begin in the usual way with a brief reference to her antecedents; even her parents’ names are unknown to me, nor can I say that at such a time and place she was born. I only know that Buncombe County of North Carolina was the place and that March 27, long enough before the Civil War so that she was grown when it began, was the time.

In my impressionable years, perhaps no one had a greater influence over me. It couldn’t have been that “like attracts like” because it would be impossible to find greater dissimilarity.

“Aunt” Emily (as everyone called her, probably because that is a title of respect that the big family that comprises the little town of Snowflake gives its older women)—Mrs. seems so formal, had come west and as was the custom of strangers came to the hospitable home of the Flakes. Aunt Emily had the key that won her a home as long as she lived. She was a Tarheel and so was Mr. William J. Flake and Anson and Buncombe Counties joined. A one-room log house with a large fireplace was her specifications for her cabin, and it must be far enough away from the “big house” so that she could feel her independence.

To most of the townspeople, Aunt Emily was a very peculiar woman. No one ever saw her cry, no one ever heard her laugh, few saw her smile. Her features were coarse, almost masculine, her stride was decidedly so; her feet were extremely large for those old days when no woman ever wore shoes bigger than size 6. Aunt Emily had to have an 8, so she had to wear men’s shoes, and for economy’s sake all but her Sunday ones were of the “clod-hopper” variety.

Her thin gray hair was parted in the middle, twisted in a tight little knot in the nape of her neck. She wore a dark colored slat bonnet most of the time in the house and out.

She could chop wood and hoe in the field like a man. Her independence was proverbial. She accepted no favors. She paid for what she got. Work was her medium of exchange. She carded wool, on shares, for mattresses and quilts, as her bed was the choicest of goose down brought West with her. Her portion of the wool she spun into yarn, knit into stockings, socks, and mittens. These she dyed with leaves, roots, barks and berries, and exchanged for the little cash she had. When anyone needed help to whitewash or clean house and to do laundry work, she was willing to go.

She had such an aversion for the uniforms of the U.S. Army that she would go to her cabin and shut herself in when the paymaster of Ft. Apache and his soldier escort made their monthly trips to Holbrook. They stayed at the Flakes. She knew about the day of their arrival, that they stayed here overnight both going and coming so she would carry in enough wood and water to last and would barricade herself in until they were gone. During the Fourth of July celebrations she would do the same. These were her most hated occasions.

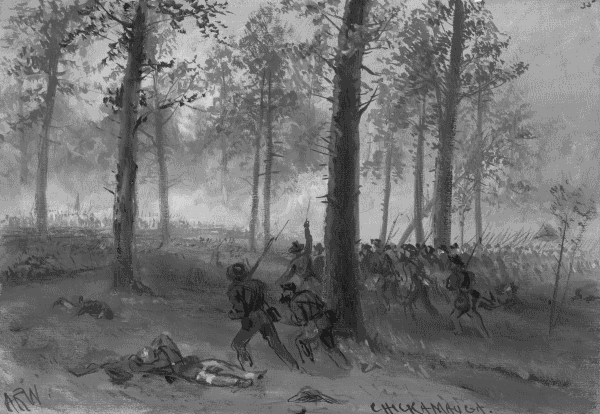

Although there is no known photograph of Emily Lanning, the violence of the Civil War, including the death of her brother at Chickamauga, greatly influenced her life. Here the Confederate line is advancing through the forest toward Union troops at Chickamauga; Alfred R. Waud, artist. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Although there is no known photograph of Emily Lanning, the violence of the Civil War, including the death of her brother at Chickamauga, greatly influenced her life. Here the Confederate line is advancing through the forest toward Union troops at Chickamauga; Alfred R. Waud, artist. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

In the good old days, the Fourth of July was the event of the year when Young America could make all the noise it wanted to. Day was ushered in by forty odd booms from the powder-primed anvils that were set off by contact with the red hot end of a long rod heated in a fire nearby. Serenaders on hayracks with organ, guitars, fiddles, accordions, and the best singers in town stopped at each house and inspired the inhabitants thereof with patriotic fervor and received in return cake, pie, lemonade, hot chocolate, or homemade beer.

At sunrise the Stars and Stripes were drawn to the top of the extremely high flag pole in the Public Square by the Flag Master, amid thirteen salutes of the improvised cannon and the shots of every gun and pistol in town from the old cap and ball, having been handed down in the Flake family from its time and only used on these occasions, to the old Sharps rifle, the .22s, the Colt .44s, and every size and make the town afforded.

Usually there was a parade of young people on horseback headed by the one fifer and one drummer and the solitary flutist, but always there was the forenoon meeting in the stake house, decorated with flags and bunting festooned from the gallery and supporting posts. Uncle Sam and the Goddess of Liberty or Miss Columbia—sometimes both—sat on the stage, while the Master of Ceremonies presided with Jeffersonian dignity.

Stirring strains of martial music were played as the townspeople assembled, called together by the church bell whose clear sweet tones can be heard two miles away. Then a fifty- or sixty-voiced choir came forth with two grand patriotic songs separated by prayer by the chaplain; then the orator of the day was introduced and with eloquence and gestures put everyone present in the proper frame of mind to do or dare anything for their country’s sake. The reading of the Declaration of Independence, a stump speech or two, usually of the comic nature, patriotic songs and recitations, punctuated at their close by booms from the anvil. On one or two occasions, when the oration became too long, the punctuation would come before the close, much to the chagrin of the orator, the relief of some of the audience, and amusement of the others. The captain of artillery always declared this was purely accidental.

The afternoons were spent in races of all sorts, all the children between certain ages, the boys and girls, the men and women, fat men’s races, three-legged ones—in which the inside legs of the contestants were securely tied together, sack races, potato and wheelbarrow races, blindfold races, and every other known kind were run. The prizes were peanuts and candy.

Then there were paper bags suspended from a tight rope; these were filled with air, nuts, candy, flour, or soot. The contestants with hands tied behind them would select their particular bags which they would jump up and tear with their teeth. Lucky was the one whose bag did not contain soot or flour. There was bobbing for apples, catching the greased pig, and many other exciting games. When this part of the program was over, then came the children’s dance, and the remaining candy and nuts were thrown on the floor and a scramble ensued to see which could get the most.

Outside of the Social Hall, a ball game would be in progress, sometimes between the married and single men, and the ladies would be torn between loyalty to their young dancers and their stalwart ballplayers. The higher the scores were on each side the more the game was enjoyed. When the games were over, all would line themselves up on the sidewalk to see the horse races, in which the best horses ran merely for amusement and to see whose horse ran fastest. Supper and chores over, then the festive day ended with a big ball at night for all over sixteen years of age, all but Aunt Emily.

I well remember the first one of these occasions after she came to live near us. All that morning I had watched for the smoke to come curling out of the chimney, or to see her around outside feeding her chickens or pig, but I did not see her. I became worried for fear she was ill, so I went to her house; the door was fastened. She had no window so I looked through between two logs where the mud “chinkin’” was out and there she lay on the bed with her head buried in the pillows. I called to her, and in a hoarse, cross voice she told me to go away and let her alone. I went and felt very badly about it until a few days after when she explained to me why she hated all this shooting and fuss, and the sight of the blue uniforms.

The tales of brutality of the Union soldiers, how they would ride by her home and with drawn swords cut off chickens’ heads to show their prowess, slash open the feather beds sunning on the fence to see the feathers fly, shoot their hogs to see them fall, commit all sorts of depredations to which even savages would not resort, until little rebel that I was, my blood would boil and I was ready like Joan of Arc to lead an army against the North and—kill ’em all. I was so serious in this that I used to take a miniature fife Santa had brought to one of my brothers and go out to Old Carney’s [Kearny’s] stable and play Yankee Doodle, and as he was a Cavalry horse, he should have known that stirring tune, should have quit munching his hay and gone prancing around the stable. He even paid no attention when I played the Reveille, Taps, or Retreat and other bugle calls—maybe that’s why the government condemned him.

Only once did Aunt Emily tell me the story that made me sob from sympathy, though her eyes were dry and flashed fury as she told me how her only brother, idolized by fond parents and six sisters, had been killed in the Battle of Chickamauga.[13] That was why she hated the uniform of blue, and everything pertaining to the Yanks.

Hers had been a most lonely life. A bride for a day, her husband had disappeared, and she never heard from him again.[14] No kindred that she ever spoke of, she was almost unknown to her associates; she had no confidants, accepted no sympathy, yet to me she was one of the most interesting people I ever knew—and I had an insight into her true life that no one else had. I often went to her lowly cabin to visit with her.

On these occasions she would sit in her low, rawhide-bottomed, homemade chair, and card wool or spin the white fluffy slender rolls into yarn as she walked rhythmically back and forth, answering my childish questions or telling me stories of the long ago. She would remove her bonnet and then the escaped strands of hair would form a soft frame about her face. When she smiled it was like sunshine bursting through clouds.

There was a time honored custom that we faithfully observed until I was eighteen years old. The night before my birthday each year, I spent with her, cuddled up in her soft feather bed; she would talk me to sleep—then the next morning she would slip out about daylight, build a fire in her spacious fireplace though it was in August. She never used her stove but cooked over the fireplace. When she would finally call me there would be delicious breakfast of my favorite dishes, fried chicken, fried hominy, fried sauerkraut, and fried peach pie, with a corn pone baked in the bake skillet.

How I looked forward to those occasions as no other in the year. One night I awoke and found myself in her arms. I was so astonished that I lay speechless, and she did not know I heard her as she poured out all the love of her pent-up soul upon me. She never knew I heard, but from then on I understood.

One time Aunt Emily accompanied my father and mother on a long hard journey of several weeks to the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple. Roads in those days consisted of a few wagon tracks. Large boulders, deep sands and unbridged washes and gullies had to be crossed. In some way, the wagon in which Aunt Emily was riding at the time tipped over. Mother was terribly frightened for fear she would be killed or badly injured, but when the wagon was righted Aunt Emily crawled out from under the cover and asked, “Where are my specs?” Typical Aunt Emily.

When the last call came to her she went bravely and uncomplainingly as she had lived, and I love to think of the joy that must have existed over there when she joined those whom she had loved and lost.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch is one of the few that RFC wrote in first person. This is all the more remarkable because Emily Lanning is not a relative and because so little is known of her. Nevertheless, she was cared for by the Flake family as if she were a relative. This is illustrated by the trip to the Salt Lake Temple dedication, of which Lanning was a part. Lucy Flake wrote in her journal, “1893 found us sad and sorryfull.” The family was still grieving over the death of her son, Charles.[15] Lucy continued, “We tried to comfort each other. the last of February my Husband came home said we would go to Utah to the Dedication [of the Salt Lake Temple] and we would have to go by team as we could not raise the money [for the train].” They left Snowflake March 8 and arrived home May 1, 1893.[16]

From census records of Buncombe County, North Carolina, it is possible to understand a little more about the Lanning family. Emily’s father, Joseph Lanning (1789−1870), was a farmer. He and Margaret Morrison (1796−1861) were the parents of six daughters and one son as follows: unidentified son who died at Chickamauga, September 1863; unidentified daughter; Zilpah/

The only census record listing Emily Lanning in Arizona is for 1900.[18] It may be that Emily Lanning died between 1900 and 1910 and is buried in an unmarked grave in Snowflake. In her journal, Lucy Flake mentions Emily Lanning as late as March 3, 1899.[19] In a sketch for Clayton’s sister, Lydia Pearl Flake McLaws Ellsworth, Emily is mentioned: “Aunt Lizzie Kartchner and Aunt Emily Lanning taught Pearl to knit, crochet, and make hair flowers.”[20] Louise Larson Comish also described Emily: “Everyone called her Aunt Emily Lanning, even though, so far as I know, she was related to no one in the town. She cooked her meals in a black kettle hanging in her fireplace. . . . She gave us some molasses candy she had made in her big black kettle. But I was more interested in her large spinning wheel and the dexterity with which she operated it, changing a soft pat of wool into a long strand of yarn.”[21]

Although Emily Lanning may be one of the unidentified women in some of the early Snowflake Relief Society photographs, there is no known image of her.

Ellen Malmstrom Larson

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[22]

Maiden Name: Ellen (Elna) Malmstrom

Birth: February 13, 1826; Ostrathorn, Lund, Malmohus, Sweden

Parents: Olof Jonsson and Karna Petersson

Marriage: Mons Larson; 1852

Children: Betsey (1853), Caroline (1855), Lehi (1857), Alof (1860), Emma Ellen (1863), twins Parley and James Moses (1865), Ellen Johanna (1868)

Death: April 24, 1914;[23] Glenbar, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Glenbar, Graham Co., Arizona

In 1826, on February 13, Ellen Malmstrom was born near the East-tower Lund, Sweden. She married in 1852. Her father was a wealthy blacksmith. Her husband Mons Larson was one of the king’s cabinetmakers.

They were members of the Lutheran church until some Mormon missionaries converted them to the LDS faith in 1859. The records in the archives of their native church say that they were well educated. On March 5, 1859, with their three children Betsey, Caroline, and Lehi, they immigrated on the ship William Tapscott to the United States.[24] It took six weeks to reach New York. From there they went by train to Florence, Nebraska, where they had to buy supplies and prepare conveyances to carry them over a thousand miles of desert inhabited only by Indians and wild animals. They were told that several handcart companies had successfully reached Salt Lake City, and they thought that surely they could do what others had done. Her husband being a mechanic, they would build their own cart and pull it to the valley of the mountains. What an example of faith and courage to their descendants.

On June 9, 1859, they started with the handcart company led by Captain George Rowley.[25] The journey was hard and tedious. The food supply was limited and the captain was harsh. He forbade them to let the oldest child, Betsey, who was not quite six, ride on the cart. This nearly broke the mother’s heart to see the little girl walking every step of the way. She always saved a crust of bread out of her own rations with which to encourage her child to keep trudging on. Betsey often said afterward that no food ever tasted so good to her.

Their baby boy became very sick, and they had very little hopes of him living, so the mother made her plans how she could prepare him for burial. But to their great joy, he recovered and was always a help and a comfort to them all their lives. They reached Salt Lake City September 15, 1859, making the journey in three months and six days.[26] However, their troubles were not ended, as they could not speak or understand English and as a result they had difficulties in their business deals.

They went west and settled in the little town of Tooele, where everyone did their own carpentering, so there was not much chance to earn anything that way. So they went into the fields and gleaned wheat for their winter’s bread. Mrs. Larson sold a gold ring for a Dutch oven in which to bake their bread, and they were thankful for the chance of digging a patch of potatoes for one-fourth as their share. Thus through hard unaccustomed labor they managed to live.

Ellen Malmstrom Larson. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

Ellen Malmstrom Larson. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

Their second son and fourth child was born in Tooele, Utah, in 1860. From Tooele they moved to West Jordan, where Mrs. Larson’s brother had located. Here Mr. Larson made a loom for his wife. She was an expert spinner and weaver and helped greatly with their income. Meanwhile she made her oldest son, now four, a pair of trousers out of sheepskins with the wooly side in. He still remembers how warm they were, and Betsey says she was never more delighted with anything than with a pair of wooden shoes for which they paid 25 cents.

While living in West Jordan, they had born to them a daughter, named Emma, and later twin boys, James and Parley. Parley lived only a few hours. In 1866 an old friend, August Tietjen, visited them and offered to give them employment if they would go with him to Santaquin in Utah County. They accepted his offer and soon had arrangements made for a farm and two city lots on which was built a three-roomed adobe house.

Along with farming, Mr. Larson spent a year building grade for the first railroad through Utah. Their eighth child, Ellen Johanna, was born January 16, 1868. On their lot, fruit trees, currants, and berries were thriving. They had teams, implements, and milk cows, hogs and chickens, and were prospering. Mines in Tintic were being opened up, which was an avenue for making money by freighting ore to the railroad, yet with all their work they had found time to beautify their home. They made a summer rest room, by setting trees closely together in a square. They made a top by bending the tops over a gable-shaped frame. It made a cool, shady, pleasant place to rest in during the hot summer days and to sleep in at nights. Tulips, hollyhocks, lilacs, roses, and other flowers beautified the grounds.

As time passed they became more prosperous so were making plans for building a larger better house, and considerable material was on the grounds when word came through the ward bishop that President Young was planning to colonize Arizona, and he wanted faithful, industrious, thrifty men with families to go as soon as they could arrange their affairs. So Mons Larson and August Tietjen were the families called from Santaquin.[27]

Their two oldest daughters had married. The oldest had three children and the other had two. Notwithstanding the sacrifice this move would mean to them, they immediately began planning for another long trek through the desert where wild animals, savages, thieves, sand dunes, and bad water prevailed. But undaunted Mrs. Larson said, “Yes, we will honor the call.”

In 1878 on October 30th, Mons Larson left Santaquin for Arizona with his wife and five children. They had three wagons and five teams, also eight head of loose stock. As they were leaving, an old friend remarked that family could settle on top of a ridge of rocks and thrive. While en route they learned of a town which had been plotted out by Erastus Snow and William Flake named Snowflake. The Larsons decided to look the place over and perhaps locate there. So it was that on December 30, 1878, they reached Snowflake and the next day chose two town lots where they pitched their tent, hauled a load of wood, and were ready to begin building another home.

Ellen Malmstrom Larson and her children. Seated, left to right: Betsey, Ellen (mother), Lehi; standing left to right: Alof (wife May 394), Emma (669), James, and Ellen (663). Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Ellen Malmstrom Larson and her children. Seated, left to right: Betsey, Ellen (mother), Lehi; standing left to right: Alof (wife May 394), Emma (669), James, and Ellen (663). Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Instead of loading their wagons with furniture and other bric-a-brac, they brought axes, plows, shovels, hoes, harrow-teeth, nails, and a case of window panes. Also a complete set of carpenter tools, wool cards, and a spinning wheel. As wool was plentiful and cheap, Mrs. Larson made arrangements for 100 pounds so she and her girls would have something to do while the men were getting out logs for a house and for fence posts. There was a good demand for all the yarn they made, and they made $1.00 a pound. Every family knit their own stockings. By the next year, they had a loom made on which they wove beautiful coverlets for beds and rag carpets for the floors. She advocated the theory that those who could do the most practical things were the best educated.

During that first spring and summer food was very scarce. Mrs. Larson searched the creek banks for something green to eat. She found plenty of nettles which she cooked with a little meat and a handful of onion tops and thickened with oatmeal or pearl barley.

One day, one of her sons remarked that people took advantage of his father, because he was too honest. She replied, looking him straight in the eye, “My son, no man can be too honest.”

In 1881 when the Atlantic and Pacific railroad was being built along the Little Colorado River, Mr. Larson and two sons helped to build several miles of grade. Mrs. Larson went along to cook for them and five other boarders, always a true helpmate, cheerful and resourceful.

Mrs. Larson labored in the Relief Society as counselor and was always willing and ready to help nurse the sick, lay out the dead, and feed the hungry. Her husband made the first coffin in Snowflake.

On account of the town being above the irrigation canal the people had to plant their gardens out in their fields. This was unhandy and caused extra labor, also prevented the planting of trees. So the Larsons became discouraged and decided to move to Pima in Graham County. In October of 1883, they left Snowflake and settled in Pima where they stayed for about three years, then took up a homestead about four miles from town. Others followed their example and it wasn’t long until a town was established, now called Glenbar.

Mr. Larson died in 1890, and his wife secured a quarter section of land through filing.

One day their daughter asked them if they ever regretted having left dear old Sweden and their comfortable home and kin folks for what they got by coming to America. They said that at first, when their trials and hardships were almost unbearable, they might have turned back if they had the means. But when they had the means they didn’t want to go back, and they felt very thankful that they had come to this wonderful country. The daughter complained that if they had not left Utah, she might have had a better education. Her mother replied, “You will never lose anything through your parents having obeyed counsel.”

When asked if their trials and privations did not make them wish they had never joined the LDS Church, the reply was that the remuneration had been more than a thousand fold. One historian has truly said: “No weaklings could conquer the desert, the Indians, the wild animals and live and develop a country. It took brave men and women who were unafraid of hard work and difficulties.”[28]

Mrs. Larson was a widow for twenty-four years. She was healthy and able to take care of herself for most of the time. She was active in Relief Society work and other religious duties. When she died at the ripe age of 88 years, she left a numerous posterity of healthy, intelligent, law-abiding citizens, numbering about 399 [in 1937]. She died at Glenbar April 24, 1914.[29]

Ellis and Boone:

Mons and Ellen Larson traveled from Sweden to Utah to Arizona. The early poverty they endured when they first arrived in Utah is illustrated with this story from granddaughter Louise Larson Comish:

Father [Alof Larson] never showed much enthusiasm for Johnny cake or cornmeal mush. He would eat it, as an example to the children, for he often told us to eat what mother set before us. There is little [that] gets past a youngster’s keen eyes. Knowing full well that father did not relish these corn dishes, I asked mother, why. She told me this story.

When Mons and Ellen Larson came to Utah from Sweden to be “with the saints in the tops of the mountains” they suffered many hardships while trying to wrest a living from the desert land in which they settled. One year when the crops of one season failed to last till the next harvest, the family subsisted almost entirely on corn. It was good food, and it saved them from starvation, but “one can get too much of even a good thing.” So far as father was concerned he would be happy if he never had to eat corn bread or cornmeal mush again in his life.[30]

Not mentioned in this sketch is the plural wife Mons married on January 23, 1876, Lorentina Olivia Anderson Eklund (1856–1935). Mons only brought his first wife, Ellen, on his initial trip into Arizona. He returned to Utah in the spring of 1879 for his second wife, Olivia, and her two children. In December 1879, when he was ready to leave Santaquin, he made the unfortunate decision to travel with the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers. David E. Miller wrote, “Had he chosen to go by the already well-established route via Lee’s Ferry he and his family would have been in their new home long before the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition crossed the Colorado, and the expectant mother [Olivia] would have had a roof over her head by the time the baby arrived.”[31] Eventually, Mons arrived at Snowflake with his second family, and then both wives moved to Glenbar in Graham County. Olivia had seven children, five boys and two girls, which survived childhood.

Only three of Ellen Malmstrom Larson's children made Snowflake their home after the Larsons moved to the Gila Valley. About 1909, these three families posed for a photograph: front row, left to right, Aikens Smith (son of Emma), Myrtle Smith (Emma), Foss Smith (emma), Josephine Smith (Ellen), May Smith (Ellen), Mons L. Smith (Ellen); second row, Emma Larson Smith, 669, Harry Wayne Larson, May Hunt Larson, 394, Ellen Larson Smith, 663; third row, Ethel Smith Randall (Ellen), Lorana Smith Broadbent (Emma), Ellen Larson, Louise Larson, Seraphine Smith Frost (Ellen), Jefferson Larson; back row, George A. Smith (Emma), Alof Larson, Hyrum S. Smith (Emma), Lehi Smith (Emma), Evan Larson. Photo courtesy of Norman Gardner.

Only three of Ellen Malmstrom Larson's children made Snowflake their home after the Larsons moved to the Gila Valley. About 1909, these three families posed for a photograph: front row, left to right, Aikens Smith (son of Emma), Myrtle Smith (Emma), Foss Smith (emma), Josephine Smith (Ellen), May Smith (Ellen), Mons L. Smith (Ellen); second row, Emma Larson Smith, 669, Harry Wayne Larson, May Hunt Larson, 394, Ellen Larson Smith, 663; third row, Ethel Smith Randall (Ellen), Lorana Smith Broadbent (Emma), Ellen Larson, Louise Larson, Seraphine Smith Frost (Ellen), Jefferson Larson; back row, George A. Smith (Emma), Alof Larson, Hyrum S. Smith (Emma), Lehi Smith (Emma), Evan Larson. Photo courtesy of Norman Gardner.

In late September and early October 1910, the Alof Larson family outfitted a wagon and traveled to Graham County to visit relatives, especially his mother, Ellen Malmstrom Larson. When they arrived in Glenbar, Alof’s wife, May, described her mother-in-law: “She looks so pale and thin, but keeps about. She is slowly dying from a cancer in the corner of her eye.”[32] May thought the cancer was not particularly painful. Ellen treated it as best she could and then would tie a cloth around her forehead to hide it. Nevertheless, it was nearly four years later before the cancer took its toll. May wrote, “Dear Grandma Larson died of cancer in her head. Poor soul has been slowly dying of it for at least ten years and for many weary months has suffered intolerably. Sister Betsy Carter [Ellen’s oldest daughter], has cared for her all this time.”[33] May Larson’s description illustrates the primitive nature of medical treatment even in 1910.

Gustella Arminta Wilkins Larson

Author Unknown, Interview[34]

Maiden Name: Gustella Arminta “Stella” Wilkins

Birth: August 13, 1874; Mona, Juab Co., Utah

Parents: Alexander Wilkins Jr. and Charlotte York Carter

Marriage: James Moses Larson; July 8, 1891

Children: James Milas (1892), Della (1894), Cora (1896), Alexander (1898), Rolland Henry (1901), Lavernal (1905), Ivan V. (c. 1908),[35] Parl Mons (1910), Ellen Dollphine (1914)

Death: October 9, 1970; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Glenbar, Graham Co., Arizona

On August 13, 1874, a beautiful, brown-eyed, black-haired baby girl came to bless the home of Alexander Wilkins Jr. and Charlotte York Carter. They named her Gustella, but they called her Arminta Gustella most of her life.[36] She was born in the picturesque village of Mona, Juab County, Utah. It was a small valley, nestled at the foot of rolling hills that were covered with foliage, plants, and wild berries.

Gustella’s paternal grandparents had integrity, courage, and powerful characters. Her maternal grandparents also had many inspiring experiences. They too gave up all their earthly possessions willingly for the gospel and went with their leaders to help make the desert blossom as the rose. When Gustella was but nine years old, her parents were called by the authorities of the Church to help colonize Arizona. They, like their parents and grandparents before them, didn’t hesitate but started preparing for the journey. Gustella’s grandmother, Sarah York Carter, was seventy-two years of age, and she drove one of the teams all the way. Gustella said, “The highlight of the trip for me was that my dear old grandmother, my mother’s mother, decided to go with us. I loved her very dearly and felt so safe when I was with her.” This grandmother was a self-trained nurse. She was always so willing to go and help when any one of her friends needed her, wherever she lived. Everyone called her “Aunt Sally.” Gustella’s grandfather, William Furlsbury Carter, was a good Latter-day Saint and obeyed the laws of the Church. He had two wives. Gustella’s grandmother was the first wife. The second wife had a young family growing up, and therefore needed a father’s help and sustaining influence. It was decided by all concerned that the right thing to do was for the grandfather to remain in Utah and rear the young family there. Gustella’s mother was the youngest of the first family, and she had a new baby. Because of the undertaking of this long and hazardous trip in a wagon, her mother, Sarah York Carter, was needed more on this trip than any place on earth. Gustella says, “I had close association with this grandmother, Sarah York Carter, until I was fourteen years old, and she told me the story many times of their joining the Church.”

The trip to Arizona was very eventful. There were about thirty-five people in the company, composed of adults and children. All the children in the company that were large enough assisted in the tasks they could perform. Gustella being the eldest in her family helped with the baby brother, who was between two and three years old. Her mother was not able, and the father had all he could do getting the team over the rough roads and hills. The baby brother would balk [refuse to walk] whenever they came to a hill. Her uncle Bill had a balky horse that would do the same. They lost a lot of time working with that balky horse, but not on account of the brother, as little nine-year-old Gustella would pick him up and carry him. She recalls the happy time they had running behind the wagons, gathering wild flowers and pretty rocks. At night when they would camp and cook the dinner over the campfire, how very good the onions and potatoes would smell! She says that even to this day the aroma of potatoes and onions cooking takes her back to that trip so many years ago.

The first time she remembers meeting the man she later married was on the top of the White Mountains during this trip. They were traveling along when they heard a noise that sounded like Indians yelling their war cry and horses running. As the sound grew nearer they discovered a white boy who was just happy to see them. He knew they were crossing the mountain and about where they were. He had known the parents of Gustella in Santaquin, Utah. He was seventeen years old. He rode up to the wagon and asked Mother Wilkins to raise the wagon cover so he could see the children. When he saw Gustella he said, “Oh, a black-eyed girl! I am going to wait for her.” After a chat he rode on to Snowflake, and the company continued their journey. Finally they reached their destination of Pima, Arizona, which was then called Smithville.

Her father’s first job after arriving was logging in the Graham Mountains. He was thankful for work after this long trip. He then started preparing to make a home for his growing family. Gustella has had experiences from colonial life to jet age progress since first arriving in Arizona. She grew up in the small farming community where the hard-working, self-supporting farmer was the most important citizen. Because there were no factories, each household had to provide for their own needs. Each farmer had a garden, raised wheat, barley, and corn, as well as cattle, pigs, and chickens.

During Gustella’s childhood there were many Indian scares; Geronimo, the notorious fighter, was often on the warpath. Indian raids were not uncommon. At this time her father and others were working out of town at a place called the lime kiln. They were burning the lime for a large two-story church house they were building in Pima. One evening he was preparing to go out to the lime kiln in order to be there early the next morning. Her mother thought he had gone, when he came in and said he had a feeling not to go until the next morning. The Indians would leave the reservation every now and then, and while on these raids would kill everyone that came in their way. That is exactly what happened this particular evening. The Indians came through on a rampage and killed a Brother Thurston who also worked at the kiln.[37] He and a friend had gone out that evening, but the friend escaped. It was a great shock to the whole community and especially to Gustella, as she and the daughter of Brother Thurston were very close friends. They sang together, and both families were very intimate. If her father hadn’t heeded the promptings of the Spirit, he may have been killed also.

Gustella also had an earthquake scare. Her father had a garden of young radishes. He had told the children not to pull the radishes while they were so small. But one day Gustella’s appetite conquered her, and as she stooped down to pull a radish the ground began to shake, moving her back and forth. She thought it was doing this because she had disobeyed her father, and she ran toward the house. In the house were Grandmother Carter and a cousin Sarah Ellen, and also her mother who was in bed with a new baby. The mother thought it was the children knocking against the bed and scolded them. The quake didn’t last long, but there was excitement all over the town, and all were very thankful when it was over.

Once again Gustella saw the boy James Larson that she had met on the White Mountains, who had vowed to wait for her. His family had now moved to Pima, Arizona. He kidded her again about being his girl and said he was going to wait for her. She, being a little shy and bashful, didn’t like it very much. After a time James went to Snowflake, Arizona, to attend high school. The next time Gustella saw James she was sweet sixteen, and he was in his twenties and a very handsome young man. Now, as he gave her more attention than anyone else, she rather liked it. With this encouragement, they began seeing each other often. Soon they knew it was real love. They were married the third of July 1891. The following month Gustella turned seventeen. She remembers her pretty wedding dress. Her mother was a beautiful seamstress, so she fashioned the creamy lacy material into a thing of beauty. “Uncle Henry Boyle,” as he was lovingly called by all, performed the ceremony. He was one of the now famous Mormon Battalion.[38] It was a quiet wedding in her parents’ home with just the relatives and close friends to witness the event. Later they were sealed in the temple for time and all eternity.

Gustella "Stella" Arminta Wilkins Larson with her natal family; front row (left to right): Gustella Arminta, Charlotte (mother), Lottie, Alroy Alexander, Edwin Granville; back row: Christa Lillis, Parley Pratt, picture of father Alexander, William Edson, and Sarah Mellin. Photo courtesy of graham County Historical Society.

Gustella "Stella" Arminta Wilkins Larson with her natal family; front row (left to right): Gustella Arminta, Charlotte (mother), Lottie, Alroy Alexander, Edwin Granville; back row: Christa Lillis, Parley Pratt, picture of father Alexander, William Edson, and Sarah Mellin. Photo courtesy of graham County Historical Society.

From this union nine children were born: Milas, Della, Cora, Alexander, Rolland, Lavernal, Ivan, Parl Mons, and Dollphine, all beautiful, healthy children. Gustella remarks that “They were such sweet, good and dependable children that all the money in the world couldn’t buy the happiness and joy I had with them.” Just six weeks before their fourth child was born, her husband received a call to go to the southern states as a missionary for the Church. Gustella encouraged him to accept the call, and they began to prepare. They succeeded in renting the farm to a good dependable man. James, who at this time was Senior President of Stake Seven Presidents of Seventies, was honored by them with a going away party.[39] Gustella was to take a cake. Now her husband’s mother was famous for her lovely cakes, so Gustella decided to make it. She made her egg beaters from willows, as even hand beaters were not known in those parts at that time. In making the cake, she had some bad luck, and it did not turn out extra nice as she had planned. Then Gustella decided she would just make a plain one. This she did and decorated the entire cake with white icing. She was very timid about making a cake for such a large party but was very proud and happy when it was cut first and passed to the presidents at the head table. Others asked for the recipe. They were invited to spend the night with the President of the Academy and his wife, as they had a long distance to travel. Sister Cluff told her how they had all enjoyed the cake.[40]

Gustella did all kinds of work to help sustain her husband while on his mission. She did such things as keeping house, taking care of the sick, and even did some sales work. The eldest daughter, Della, was just four years old but assisted her mother. She did her part at that early age to help keep her daddy on a mission. Many helped during this time, but especially the parents who lived on either side of her, and within walking distance. Therefore, James was able to complete a mission of over two years.[41]

James and Gustella were living in Globe when the first LDS church was built. Her husband’s allotment was assigned to him, and since the families were given the privilege of working on the church or paying in cash, James chose to spend all his spare time working on the building.

All the children had true voices. Gustella had always loved to sing and had passed this talent on to them. She commenced teaching them songs very early. At this time the three eldest, Milas, Della, and Cora, were in school. They had learned a song entitled “This is the Way to Make a Shoe.” Just a short distance from them lived an elderly couple. The man was a shoemaker, and the woman kept boarders. A friend of the Larson family, a young girl named Helen Greenhalgh worked for them in the boarding house. The children loved to go and visit her because she was so good to them. One time during one of these visits, Helen asked them to sing to the old cobbler. They sang the Shoemaker song. It won the old man over heart and soul. Until this time, children had annoyed him, as they were always getting into his tacks, hammers, and tools. He gave the Larson children a very fine compliment. He said that he loved to have them come. They were so well trained and had such good manners, and they never bothered his tools or equipment. They loved the old shoemaker, and he never tired of hearing them sing. Later Helen became their aunt as she married their Uncle Ed.[42]

Gustella has been active in the Church all her life, working in the various organizations. At fourteen years of age she was secretary of the Sunday School in Matthews Ward. Later she was counselor in the Primary when Laura Smith was the president. She was the branch superintendent of the Sunday School in Miami Ward. She was a teacher in both Primary and Sunday School in the Phoenix Third Ward. She has always loved her Relief Society and served in the presidency of the Miami Ward. She did Relief Society teaching for many, many years. In her early married life she would put her baby in the carriage, and the other children would trudge along the dirt road. They would all walk for miles to make all their visits. At eighty-six years of age, she was the oldest active visiting teacher in the East Phoenix Stake. She was a visiting teacher for about sixty years.

Although Gustella was an extremely busy wife and mother managing a family of nine (all but one grew to adulthood), she not only found time for her church work, but she fashioned, designed and made dozens of crocheted articles and braided rugs. All her children’s homes are adorned with her beautiful work. She won the blue ribbon at the State Fair in 1954, for her lovely braided rug. She had dyed the colors and designed it, then crocheted a scalloped edge. She sewed the braided strips together so skillfully that the stitches couldn’t be seen. At this time she was eighty years of age.

Gustella and her husband, James, felt their greatest achievement in life was raising honorable citizens and loyal church workers. Seven of the nine children filled missions for the Church. They have twenty-six grandchildren, ninety great-grandchildren, and six great-great-grandchildren. Doctors, lawyers, merchants, F.B.I. special agents, teachers, etc. are to be found in their posterity. All her children and grandchildren are devoted to her and call her beloved.

Ellis and Boone:

Although James Larson died in 1937, Stella lived until 1970. As such, her life bridges the pioneer and modern eras in the history of Mormons in Arizona.

Possibly one of the most important contributions the Larsons made to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was the time that they lived in the non-Mormon mining towns of Globe and Miami. As a Globe bishop, Ardell Ellsworth wrote, “Mormon families soon found that the copper mining towns of Globe and Miami, eighty miles west of Thatcher, offered employment opportunities.”[43] When Nathaniel Nelms first came to Globe, he found few with any sympathy toward Mormons. Consequently, he did not let people know his religion until he had won the respect of employers and townspeople. Then he encouraged other Mormon men to seek work at Globe; a branch was organized in 1906 and a ward was organized one year later. As Ellsworth wrote, “By 1913 the brethren were working in the mines, in the dairies, as clerks in banks, stores and railway offices, etc. They earned a fine reputation for veracity, reliability and honesty. Instead of being shunned and hated as they were in the beginning, they were now given preference by employers.”[44]

The few Latter-day Saints living in Miami, just west of Globe, found religious worship more difficult. They “had to make the long-rough journey into Globe,” and consequently “received most of their religious training in the home.”[45] Then, a dependent branch of the Globe Ward was organized in 1912. Not only did James and Stella Larson live in Miami, but Lehi, another of Ellen Malmstrom Larson’s sons, also lived there and served in the branch presidency for ten months.

Most of the LDS families living in Globe and Miami came from the upper Gila Valley along with a few others who came out of Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. The Miami Ward history noted that “as is typical in a mining town, families came and went, but some of the early faithful families were: the . . . Joseph W. Greenhalgh, . . . Edwin Wilkins, . . . Jimmy [James Moses] Larson, . . . families.”[46] During the Great Depression years, many mining jobs evaporated, and the Miami Ward was discontinued for a short time; the Globe Ward continued to function but with far fewer members. During World War II, many of the shuttered mines were reopened, and church membership in the area rebounded. Finally, in 1974, there were enough members in the Globe-Miami area to create the Globe Arizona Stake, but the Larson family had moved on to Phoenix, and Stella Larson had passed away.[47]

May Louise Hunt Larson

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP/

Maiden Name: May Louise Hunt[49]

Birth: May 5, 1860; San Bernardino, San Bernardino Co., California

Parents: John Hunt[50] and Lois Barnes Pratt[51]

Marriage: Alof Larson;[52] October 26, 1881

Children: Alof Pratt (1882), Hugh Malmstrom (1884), Lois (1886), Wallace Hunt (1887), twins Evan J. and Ivan G. (1889), Ellen (1891), Louise (1894), Hapalona (1896), Jefferson Daley (1897), stillborn (1901), Harry Wayne (1903), stillborn (1907)

Death: May 4, 1943; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Coming from a line of school teachers on her mother’s side, it is no wonder May Hunt Larson was blessed with an exceptionally brilliant mind; this combined with the determination of her Grandmother Celia Hunt to master difficulties who at the age of seventy-one years learned to write, the courage of her grandfather, Captain Jefferson Hunt of Mormon Battalion fame, and the leadership of her father John Hunt who for over thirty years directed the affairs of the town of Snowflake, as bishop of the ward, made her an invaluable asset to any community.[53]

May Louise Hunt Larson. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

May Louise Hunt Larson. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

She was the daughter of John Hunt and Lois Pratt. She was born May 5, 1860, in San Bernardino, California, the second of eight children, six girls and two boys. When she was nine months old, she was very ill with influenza, which deprived her of the sight of one eye; but somehow she has managed to see as much and read and study more than most people with two eyes.

When she was three years old, her parents moved from California to Beaver, Utah. Here she went to her first school as soon as she could talk well, her mother’s sister, Ann Louisa Pratt, being the teacher. Later she attended school taught by her grandmother, Louisa B. Pratt, and to the school of another of her mother’s sisters, Ellen Pratt McGary.[54]

She has little cards of merit from these teachers today, also one from Lucinda Lee, teacher when she was six and one-half years old entitling her “to sixty marks of credit, each of which denotes one lesson well recited.”

From thirteen to sixteen years old, she was a member of a select private school, taught by Richard S. Horne, or Teacher Horne as his pupils called him. This was the last school she ever attended. She taught a little class of girls in Sunday School, in Beaver, Utah, when but fourteen years old, and took part in a big Sunday School Jubilee, July 24, 1874.

In October 1875, her father moved to a little place called “The Cove” on the Sevier River. They had to go two and a half miles to Joseph City, the nearest small town to church and Sunday School, but were seldom absent.

When she was sixteen, she went down to Dixie, Southern Utah, where she spent a happy summer at the home of her Aunt Lydia Hunt, in Duncan’s Retreat, a small place, later washed away by the Virgin River.[55]

In February 1877 her father decided to come to Arizona or New Mexico and President Brigham Young wrote him personally, giving him permission to locate at any of the colonies he might wish to join. They went down to St. George, the last town in Utah, traveled due south and crossed the Big Colorado at the Pearce Ferry, then through Walapai [Hualapai] Valley to Peach Springs and east to the Little Colorado, passed through Sunset and Brigham City, now Winslow and Joseph City, then east landing in San Lorenzo, New Mexico, thirty miles east of the Zuni village. They moved to Savoia Valley, twenty-five miles from Ft. Wingate, a soldier post, from which they got their supplies, arriving there June 1, 1877.

Here they had a terrible siege of smallpox for three months. The father, mother, and three older girls escaped it, owing to vaccination in California. The five younger children had it—some light, some very heavy, but all came through safely.

They made many warm friends among the Navajo and Zuni Indians. They would lend them money or clothing to wear at their dances, which were always returned.

In September 1878, her father answered a call to be the bishop of the new town of Snowflake, which had been created from the ranch of James Stinson on Silver Creek, a tributary of the Little Colorado, which was bought by William J. Flake July 1878. The family arrived in December 1878. The family of Mons Larson arrived about the same time. Here May has lived continuously except for short visits to different places.

A Sunday School was organized the first Sunday after their arrival, and May was chosen as teacher, chorister, and librarian. Also in a Young Women’s Organization, she was chosen as a counselor to the president.

The welcome the Larsons received from Bishop Hunt, his warm personality, and thoughtful kindliness made them feel at home. Mons was a master carpenter from southern Sweden and his wife an artist on the loom. They had many talents to offer a new community.

Alof was quick to note the bishop’s attractive, rosy-cheeked, brown-eyed daughter, May. Soon he was calling regularly at the Hunt home. For the rest of his life, the story of this stalwart Swedish boy would be entwined with that of May Hunt, for Alof asked her to be his bride. She gave her promise, and they made plans for a trip to the temple.

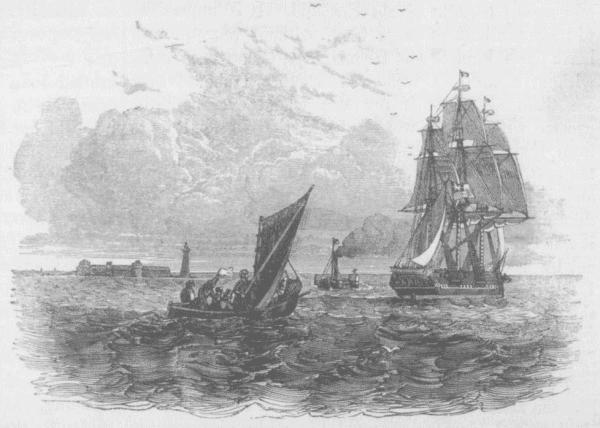

In 1881, the Atlantic and Pacific railroad was being pushed into Arizona from the east. Alof secured a job on this project, building grade, which netted him “cash in hand,” something almost unknown in an era of barter and trade. For 300 hard earned dollars Alof purchased a span of mules. That fall these mules were on their way to Utah, drawing one of five wagons making the trip over Lee’s Ferry. This was the first wedding party from Arizona to go north to a Utah temple, but so many future ones were taken across this ferry that the road was dubbed by Will C. Barnes, “The Honeymoon Trail.”[56] Alof was chosen Captain of this expedition by popular vote. Alof’s sister, Emma, and her husband to be, Jesse N. Smith, President of Snowflake Stake, were members of this party.

Although their start was made in a drizzling rain, the remainder of the journey was blessed with fair weather. Everyone was in high spirits, the miles slipped by without incident or mishap. In twenty days, the party traversed the four hundred miles to their destination. On October 26, 1881, Alof Larson and May Hunt were married in the House of the Lord by the President of the St. George Temple, David H. Cannon.[57]

By December 5, Mr. and Mrs. Alof Larson were back in Snowflake. May’s journal reads, “We began housekeeping in a very primitive way.” There was not a room to be had, so they pitched a tent for themselves. This domicile could not withstand Arizona’s vigorous breezes. They toppled the fragile shelter more than once. When road conditions permitted, Alof would drive his mules to Pinedale for a load of sawed logs. Soon he began construction of a one-room log house. This was the first unit of the only home the Larsons would ever know.

In this home, May gave birth to thirteen babies, nine boys and four girls. The only help received in her deliveries was afforded by local women. They were “called and set apart by the Priesthood to act as nurses and midwives among the people.” Their training was received largely in the school of experience. Six of May’s babies died, two in infancy, two in young manhood, and two full-term males were stillborn.[58] The remaining seven grew to maturity and married. Alof and May were made happy with twenty-nine grandchildren. And they lived to see some of their great-grandchildren, having been privileged to observe the 57th anniversary of their marriage. As they journeyed into the sunset, they were appreciative of their family, of the companionship and thoughtful consideration that the children and grandchildren afforded them. And their hearts were warmed by the knowledge that the children were doing their share of the world’s work.

May Hunt Larson with her children; Jefferson Daley on lap, other children (left to right) Wallace, Louise, Evan, Alof Pratt, Ivan, Hugh, and Ellen. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

May Hunt Larson with her children; Jefferson Daley on lap, other children (left to right) Wallace, Louise, Evan, Alof Pratt, Ivan, Hugh, and Ellen. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

Always active in church work, May was teaching a Sunday School class when she was fourteen years old, the beginning of many years of service in this organization. In the YLMIA, May was a counselor for both Ward and Stake; four years she was on the Stake Genealogical Board; and in the Relief Society she was assistant secretary, secretary, teacher, and counselor. Then for sixteen years she served as President of the Snowflake Relief Society. In this organization, with a prayer in her heart, she served her community.

As a mark of endearment, she was called “Mazie” by her sisters. Most of the town’s inhabitants called her “Aunt May.” No one was refused who came to her door asking to be fed. Her friends were to be found wherever she was known. In times of rejoicing, folks liked to have her with them, for she could be gay. In times of trouble, she was a source of strength and comfort. Her memory was proverbial. She gave readings on a variety of subjects. As a public speaker, May was fluent, understanding, and poised. In her later years, she was often asked to speak at a funeral.

In 1931, she and her husband celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary, surrounded by hundreds of friends and relatives from far and near, who joined in wishing them many years of continued happiness together. When Snowflake Stake honored Alof Larson at the end of three decades as counselor in the Stake Presidency, his wife came in for commendation also. Note this salute: “‘Aunt’ May Larson . . . devoted wife and helpmate of our honored guest; wise and beloved counselor of the mothers and daughters in Zion, with a heart large enough to mother the entire stake . . . .”

May was a great reader and selected the best that she found to put in the scrapbooks she was making for each of her children’s family. She kept, however, the one she began in her childhood, which contains many choice selections in prose and poetry.

A remarkable woman in very deed and one whom to know was to value very highly. She had been a mother to her motherless brothers and sisters and to all the motherless, and a true friend to all widows and fatherless. The tributes she received on her birthdays and Mother’s Day, from widely spread sections, testified to the great circle of friends that were hers.

In January 1939, Alof passed away suddenly from a heart attack. Seeking solace in temple work, May lived on for four years. Then cancer struck. Ellen nursed her mother through her short illness with such skill that training and experience had given her that May died peacefully without knowing the nature of her affliction, May 4, 1943.

Ellis and Boone:

In 1978, granddaughter Ilene L. Shumway added to this sketch. She wrote:

In my teen years, May was not able to do her work. It was due to arthritis in her knees and so a Saturday assignment for myself or one of my sisters was to clean Grandmother’s house. Floors were covered with throw rugs that all had to be taken out and shook. Not hard, but gentle. Dusting to do and kitchen floor to mop and change the sheets on the bed. There was a pan of clabber on the table for Grandpa when he came in from the field and he would sprinkle a little sugar over it and say, “Try some, sissie. It is good.” But I could never do it. Grandma kept the best kettle of hominy [in] the back room. To dip my hand into it and eat was so delicious. And her molasses cake, her cookies of various shapes and sizes and BIG. . . .

One could not do wrong in Grandma’s house for all around the room were pictures of grandmas and grandpas, looking right at you. Grandma also had a rocker that had a secret drawer in it. This was fun to sit in and imagine the treasure in the secret drawer.[59]

On February 4, 1894, Andrew Jenson of Salt Lake City visited the Snowflake Stake. Jensen and Stake President Jesse N. Smith spent two weeks traveling to Joseph City, Obed, Sunset, Woodruff, Snowflake, Taylor, Pinedale, Juniper, Adair, Pinetop, and Woodland collecting “historical facts” and preaching.[60] May Hunt Larson wrote, as the first entry in her journal, “In the spring of 1894 Andrew Jensen, assistant Church Historian came to our ward (Snowflake), and in gathering up records, dates, etc. he advised all families to keep a record and a journal. In compliance therewith, I, May Hunt Larson, concluded to try and write a little of our lives for future use.”[61]

Although this event was also the impetus for Lucy Hannah White Flake’s journal,[62] May Hunt Larson came from a family of journal writers, and so it is somewhat surprising that this was the beginning of her journal writing.[63] In 1916, RFC wrote in her own journal, “Aunt May Larson and I were talking last night about keeping journals. She thinks all they are for is to write down what you do, for instance, ‘Monday, washed and knit.’ I told her in 50 years her people wouldn’t care when she washed or knit, but what she thought about while she was doing it. I read her a few pages from mine.”[64]

In 1956, daughter Louise Larson Comish wrote a short essay called “Mother and Her Journal.” She began:

Looking back it seems to me that writing her journal was Mother’s hobby—something she enjoyed doing. I remember that as a child I got the impression from watching her as she wrote in her book that it seemed to give her real satisfaction. It was a sort of relaxation from the ordinary chores of home making. She wrote easily and well. Holding her pen with relaxed thumb and fingers she would dip the shiny point in the square bottle of ink and methodically without haste, fill line after line of each page of her book. She apparently had no difficulty formulating her thoughts for her pen moved quite steadily unless interrupted by household demands. She had a real genius for spelling and could quote the rules for the placing of vowels, so there was no stopping to look up words in the dictionary. Yes, I believe she liked to write. She was well known for her good letters—long and “newsy”. This I am really in a position to appreciate since I received her letters regularly from 1913 until her death in 1943. These letters, written usually at the first of each month, contained much of the material that found its way into her journal. . . . This is my version of how she “did” her journal. By the kitchen window where she had her sewing things, could usually be found an ordinary pencil tablet like school children used. In this she jotted down things she thought should go in her journal. On the window sill were letters, on the backs of some could be found other notations. At one time I remember, she had a paper hanging on the back porch on which she had written the names and dates of new babies as they arrived in Snowflake. In no sense I feel, was this journal a diary in which she made a daily record, a place where she gave vent to frustrations or told little secrets. It was more like a record of her people as advocated by her church. . . . When she had a day free for writing, one would find her in a fresh apron sitting at the front window her record book open and the leaf of the sewing machine and the pencil tablet and other notes on her lap, carefully she recorded in permanent form the thought she wanted in her book. . . . These volumes represent many woman-hours of work, a labor of love, done largely for the joy of doing it.[65]

May Hunt Larson’s journal has become an important source for Snowflake history, in part, because she continued it until her death in 1943.[66]

Cynthia Abigail Fife Layton

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Cynthia Abigail Fife

Birth: July 22, 1867; Ogden, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: William Nicol Fife and Phebe Abigail Abbott[67]

Marriage: Joseph Christopher Layton; September 2, 1886

Children: Joseph Christopher (1887), Glenna Seline (1889), Edna Cynthia (1891), William Walter (1892), Iretta (1894), Phoebe Caroline (1896)

Death: December 14, 1943; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Possibly one of the most trying experiences any pioneers ever encountered were endured by the family of Mrs. Cynthia Layton, when upon arising one morning, many miles from any settlement, they found their team had strayed away, and they were stranded on the desert. On their way to help settle Arizona they had faced many difficulties, but this was the worst. There they had to remain until the runaway horses could be found, and that took several days. This was in 1880, when William N. Fife left his home in Ogden, Utah, to go in search of a new home. November is a bad month to start on such a journey, but with the delay it was almost unendurable to the mother and children.

Cynthia was born in Ogden, July 22, 1867. Her parents were William N. and Phebe Abbott Fife. Her life has been anything but a happy, sheltered one. But through it all she has gone bravely, as befitted a pioneer.

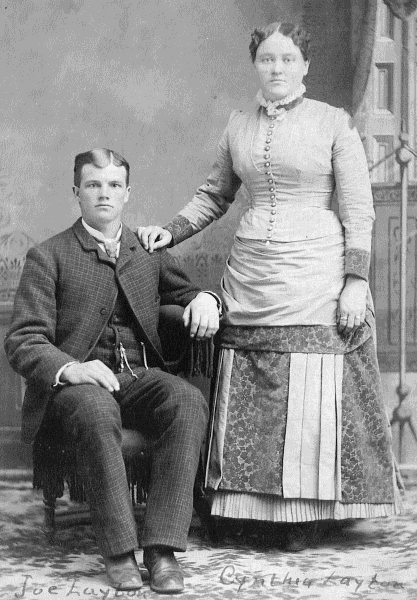

Cynthia Fife Layton with husband, Joseph C. Layton. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

Cynthia Fife Layton with husband, Joseph C. Layton. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

The first home the family had in Arizona was in Smithville, now known as Pima, but they did not remain there very long. The next move was to the Chiricahua Mountains, where her father took up some land, and they made their home there. Three of her brothers, John, Orson, and Walter hauled timbers from these mountains for the mines at Tombstone.[68] The country was new, and they experienced many unpleasant things.

It is hard to tell which was the worst menace to those early settlers: the rustlers, the Mexicans, or the Indians. The Laytons were not molested by the rustlers, but one of Cynthia’s aunts was killed by a Mexican. He was going through the country and found her and her daughter alone. He shot her and tried to kill the daughter. The infuriated neighbors found him and hung him to a tree near the house.[69]

The Indians kept them in constant fear for many years. Her brother John and two other men were in the mountains getting out mining timber when they were surrounded by Indians. The two other men were killed, and John was shot three times, but miraculously escaped death.[70] Sacks filled with sand were heaped high inside the house to be put in the doors and windows in case of an attack by the Indians.

Cynthia did not have much chance for an education, but she was a keen observer and made the best of her opportunities.

On September 2, 1886, Cynthia was married to Joseph Layton, a son of the famous pioneer, Christopher Layton, who did so much for the pioneering of Cochise and Graham Counties.[71] As soon as they were married, they went to St. David to live. They only stayed there a year, and then moved to Thatcher where their oldest child was born. They built them a nice home but only stayed there a short time, then went to Layton, Arizona, took up a farm, and built themselves a small house.

Her husband decided to go into the cattle business, and so they moved back to St. David. Tiring of this, they moved to Thatcher, built another home, and went into the mercantile business.

One of the saddest things that Cynthia endured was when her little three-year-old daughter died of blood poisoning. This was her eldest daughter and a very promising child.[72]

The store business proved to be too confining for her husband, and so they traded it to his father for a farm. They were only there three months when her husband passed away and left her with five small children, the youngest a baby girl of eight months.[73] Thus Cynthia was widowed at the age of twenty-nine years, leaving her with a great responsibility of facing the hardships of life without a companion, and with a necessity of providing for herself and her small children. Only by the hardest of work, the strictest economy, and good management was she enabled to do this.

Her only recreation was in her church work. She held positions in the Sunday School and Relief Society, and served in the Primary for twenty years. Seventeen years of that time she was Stake President of that organization.[74] She had to travel from one town to another visiting the different ward organizations. For many years she was a member of the Ward Choir and enjoyed singing very much. This helped her drive the blues away.

The most tragic experience through which Cynthia has been called to pass was when her youngest son, employed at the Industrial School, was hit on the head with an axe by one of the inmates and killed. He left a wife and three children.[75] Having endured widowhood and the rearing of her own little family, her heart went out in sympathy to her daughter-in-law, and for her sake she tried to be brave.

Building of homes did not cease with the death of her husband as she has built two more during her lifetime. She spent two winters in Mesa at the Arizona Temple. She has just cause to be proud of her family, as they are all honorable members of society.