K

Roberta Flake Clayton, Ellen Greer Rees, Olena Olsen Kempe, Charlotte Kempe Mangum, Effie Kimball Merrill, Andrew Gordon Kimball, and Orson Conrad Kleinman, "K," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 339-376.

Annella Hunt Kartchner

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Annella “Annie” Hunt

Birth: February 15, 1862; Colton, San Bernardino Co., California

Parents: John Hunt[2] and Lois Barnes Pratt[3]

Marriage: Orin Kartchner; October 11, 1883

Children: Celia (1884), Kenner Casteel (1886), Jane (Jennie) (1888), Thalia (1891), Lafayette Shepherd (1893), Sarah Leone (1895)

Death: March 6, 1946; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Annella Hunt was born February 15, 1862, at Colton, California, near San Bernardino. Her parents were John Hunt, son of Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion, and Lois Pratt Hunt, a lady of high culture and beauty. Their home at the time of Annella’s birth was located near the Santa Ana River, and on the morning of February 15, as the family was seated at the breakfast table, their house was surrounded by flood waters, overflowing the low banks of the river.

John Hunt hurriedly hitched up his team, and they drove to his sister Harriet Mayfield’s home, situated on higher ground farther from the river. Here, at midnight of that day, Annella Hunt was born.

The Hunt family remained in California until Annella was a year old, then made the long journey by team across the great American Desert and settled in Beaver City, Utah. Their three small daughters had whooping cough during that journey, and they had a terrible time, as it was a serious form.

Just before leaving California, John Hunt had all his family vaccinated for smallpox, even baby Annella just past a year old. This precaution proved to be a very great blessing to them all fifteen years later.

They lived in Beaver for eleven years, where the family went to good schools, and besides the three older daughters, two brothers and three other sisters were born. John Hunt was sheriff of Beaver County during the entire time, and his family had many anxious times when he was after men who had committed serious crimes or had escaped from the jail.

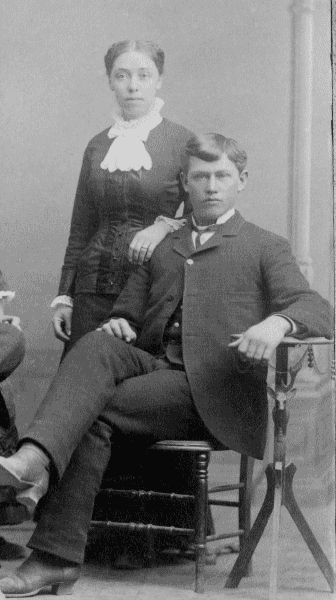

Annella Hunt and Orin Kartchner, 1883. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Annella Hunt and Orin Kartchner, 1883. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

He finally decided to move away from Beaver and took his family to a small settlement on the Sevier River where they remained for two years. They next joined a group of pioneers who were going into Arizona or New Mexico, where new settlements were proving successful. It was a sad event in the lives of the parents and older children to bid farewell to their dear ones and lifelong friends.

The long journey was begun the day after Annella Hunt’s fifteenth birthday, February 15, 1877.[4] The company was composed of twelve covered wagons, some horse teams and some oxen, with a herd of loose animals to be driven.[5] As they journeyed through southern Utah, they often suffered from heat and lack of water. At one time their loose animals went without water for fifty-six hours. They crossed the Colorado River on the lower ferry, called Pearce’s Ferry. They were familiar with all fresh watering places and springs, from men who had gone ahead to blaze the trail and open the unknown wilderness for the hardy ones brave enough to take their families and build homes in the barren valleys where only Indians had ever lived.[6]

By the time they reached the foot of the San Francisco Mountains, they were travel-worn and some of their teams gave out, so they camped for a week. At such times, the mother and older girls would do the family washing, being prepared with tub and washboard for this purpose. Also, they would bake many loaves of bread, having learned to “set a sponge,” and do all the other necessary processes of bread making around a campfire.

Here at this camp John Hunt was able to exchange cows and oxen and loose horses, for a fine team of American horses, to continue the journey. But again there was a shortage of water, and one night in April 1877 as they were crossing the long desert between what are now Flagstaff and Winslow, Annella Hunt and her brother Lewis were walking, driving the loose cattle. Suddenly, the girl discovered a white object up in a tree. She found it to be writing paper, and knew it must be of great importance to them. She and her brother stopped their father to tell him of the discovery, and he at once lighted the lantern, and found it to be a notice of two large tanks of water not far from the road.[7] It had been left for their benefit by men who had gone ahead.[8] Hurriedly unharnessing the teams, the company spent two hours getting their thirsty animals down into those rocky tanks to be watered. They were very thankful for the finding of that little piece of paper, for they felt that it was a providential guidance to keep them from perishing.

When they reached the settlement of Sunset on the Little Colorado River, they rested there for two days. The leaders there urged them to remain and make their home with the Sunset Colony, but John Hunt decided to go on to the settlement in Savoia Valley, New Mexico. Two missionaries to the Indians were already there with their families, but outside of four or five families, the chief settlers of Savoia were Navajo and Zuni Indians and Mexicans.

However, these native inhabitants proved to be civilized enough to become good friends of the white settlers, especially in times of distress and sickness.

During that summer of 1877, Annella Hunt taught a little school under a bowery. Her own younger brothers and sisters and children of the other settlers were her pupils, and her salary was a new dress, given by Mr. Boyce, as payment for her teaching his boys.

During the late fall of 1877, a company of Mormon emigrants arrived in New Mexico from Arkansas. The family of Thomas West had contracted smallpox from camping in a Mexican house in Albuquerque, when the mother gave birth to a pair of twin babies. They drove on to the Savoia settlement, all of them either ill or exposed to the disease. John Hunt and his family cared for them and for others who took the disease throughout the long cold winter in the most terrible siege of smallpox that could be imagined or endured.[9]

Those who had been vaccinated fifteen years before, even Annella who was only a baby, escaped the disease and were called upon to their uttermost physical endurance to nurse the sick ones and to lay away those who died. The three younger sisters and two brothers all had smallpox in a quite serious form but none of them died.

In the fall of 1878, John Hunt was called to be the bishop of the new Snowflake settlement on Silver Creek. His family hailed the change with delight, as the Savoia settlement had been so isolated and lonely.

Now began Annella Hunt’s long, active life in Snowflake, where she served in every sort of public capacity. She was the teacher of the first little school in Snowflake, in the spring of 1879, which she taught in one of the little adobe stables built by Mr. Stinson who was the first owner of the site of the Silver Creek settlement. It had been carefully cleaned for a meetinghouse. She did not keep the names of her pupils, but has always wished she had, for very often a man or woman past middle-age will come to her and say, “I was one of the pupils in that first little school, which you taught in Snowflake.”

The following winter, she also taught the first school in the town of Taylor, three miles south of Snowflake. In the fall of 1881, Annella Hunt and her eldest sister, Ida Hunt, taught the Snowflake school, and in the spring of 1882, they taught the school in Taylor. Three or four months were as long as county funds permitted the schools to continue.

The three oldest Hunt sisters, Ida, May, and Annella, had passed a teachers’ examination under Mr. James Stinson, who was county judge, and they held certificates which entitled them to teach in Arizona schools. Annella taught altogether seven terms of school, most of them of only few months’ duration.

In September 1883, Annella Hunt left her home to become the bride of Orin Kartchner. They made the long journey by team, to be married in the temple at St. George, Utah, traveling in company with a brother of the bridegroom. They were married October 11, 1883. They remained in Utah nearly two months, the young husband helping with threshing and harvesting, then visiting with relatives and friends in Beaver and Richfield. They reached home December 17, 1883.

Their home was one log room on the old Kartchner lot, the present site of Annella’s younger sister, Mrs. Nettie Hunt Rencher’s home. On November 30, 1884, their sweet little baby Celia was born. She filled their hearts with joy but was not to remain with them to grow to womanhood.

Annie Hunt Kartchner with some of her siblings: front row, left to right, John Addison Hunt, Annie, Lewis Hunt; back row, Lois West and Nettie Rencher. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

Annie Hunt Kartchner with some of her siblings: front row, left to right, John Addison Hunt, Annie, Lewis Hunt; back row, Lois West and Nettie Rencher. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

When she was three months old, the saddest event that ever came into the lives of the Hunt family occurred in Snowflake. Their mother, Lois Pratt Hunt, was accidentally burned so badly that she died a few hours later. Annella’s baby was asleep in a rocking chair in the room. In the brief excitement, the baby was forgotten for several minutes, when someone suddenly asked, “Where’s the baby, Annie?” As she rushed in to see if she was all right, a brother-in-law placed her in Annella’s arms, but bits of burned hair and clothing were all over her, though she herself was unharmed. The sweet little one lived to be one year and one week old and was then taken from her loving parents, leaving their hearts desolate.

Mrs. Kartchner was a member of the first dramatic company organized in Snowflake, and for many years she acted in plays of all sorts with important roles. The last time Uncle Tom’s Cabin was played in Snowflake, a committee visited Annella with an insistent request that she play the part of Topsy, which she had successfully portrayed many years before. She felt that it would be impossible, as she was at the time fifty-two years old. Finally she consented to take Topsy if her brother John A. Hunt could be persuaded to take Uncle Tom. Such was the ability of these two, in connection with a fine supporting cast, that a most excellent portrayal of these famous Negro characters was presented to an enthusiastic and appreciative audience.

When the play The Two Orphans was presented, Annella Hunt Kartchner was selected as the blind girl Louise, the sister Henrietta being Roberta Flake. A most touching and beautiful performance was given of this famous French play.

The last part Mrs. Kartchner played was in The Old-Fashioned Mother, when she was fifty-seven years old. Such was her dramatic ability, that when she was to weep in her part, she actually shed real tears, and in this old-fashioned mother, so vividly did she portray the pathos of a mother deserted, and about to be sent to the Poor House, that sobbing could be heard from every part of the auditorium of the theater.

Her guitar playing, both in playing tunes and accompaniment for singing, and her beautiful alto voice have always been a special feature of the famous “Hunt Sisters” singing. Her voice was still rich and mellow and remarkably preserved at the age of seventy-four.

She had a real poetic talent, which seemed to develop after her third or fourth child was born. While in her thirties and forties, she did a great deal of composing. She had about forty poems, especially songs, for some of which she also composed the music, to her credit. Her most important efforts were two epic poems, one for her brother-in-law, David K. Udall’s fiftieth birthday, September 7, 1901, written by special request of her sister Ida Hunt Udall. The other was for the golden wedding celebration of Bishop John Bushman and his wife, February 11, 1915. Many a farewell and reception, many a sad heart at times of death and affliction, many a birthday, and occasions of all sorts have been enriched and enlivened by a song or poem from her pen, with its personal touch and cheering tone.

In her own church, Annella H. Kartchner has held many positions throughout her life, and has been active and faithful in the performance of every duty, in all the organizations as secretary, counselor, teacher, song-leader, and as ward clerk over a period of ten years.

She never had very good health, even when she was a child. She had in her lifetime several serious illnesses, among them, “septic sore throat,” as it was called, typhoid fever, pneumonia, and once a serious attack of what was known as “quick consumption.” But her wonderful faith, her strict obedience to the Word of Wisdom of her church, and careful observance of simple rules of health, preserved her life to a good age, with fair health and retention of her faculties to a marked degree. She has borne six sturdy children, two sons and four daughters; all but the first baby girl survived her. They are K. C. Kartchner, Lafe S. Kartchner, Mrs. Jennie K. Morris, Mrs. Leone K. Fulton [later Decker], and Miss Thalia Kartchner [later married David Butler].

The Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. and Mrs. Kartchner was celebrated at Snowflake in 1933, with an excellent program composed throughout by the sons and daughters. Two special features of this program were a duet sung by Mr. and Mrs. Kartchner, with guitar accompaniment, and a guitar duet which they had played together at the time of their marriage.

They continued playing their beautiful music until the time of her death. Annella lived to celebrate her 60th wedding anniversary with her family and relatives and friends. Her daughter Thalia had secured a school in Mesa so made a home for her parents there. Her father spent much time at the temple, but due to her failing health, Annella could not attend. After her eighty-fourth birthday on February 15, 1946, she continued to grow weaker till on March 6, 1946, she passed peacefully away. Beautiful funeral services were held at Snowflake March 10, 1946, with tributes in song, with tender loving words, and beautiful flowers. A marble headstone marks the sacred spot where she lies in the cemetery. Time lessens the loneliness, but such a mother leaves behind a bright memory of the beauty she created for a loving family, which enriches our lives forever and can never die.

Ellis and Boone:

The book Frontier Fiddler is a memoir of Annella’s oldest son, Kenner Kartchner. The main theme of this book is Kartchner’s love of music. He wrote, “Both Mother and Dad played the guitar and sang. Mother also was one of the Hunt sisters who were locally famous for their beautiful singing. I was taught to sing and play guitar accompaniment at scarcely seven years of age. At twelve I began playing an undersized violin, a sweet-toned copy of Stradivarius.”[10] An accompanying CD has many of Kartchner’s early fiddle tunes, and an appendix describes dance steps that the pioneers used for these waltzes, schottisches, two-steps, polkas, reels, and hoedowns.

In discussing his childhood, Kartchner gave the following description of his mother: “Mother had a brilliant mind, a good education for her time, and spoke faultless English. Her breadth of vocabulary and general knowledge were quite the exception in a frontier community with limited ‘book larnin.’ She patiently answered my thousands of questions on any and every subject and taught me to read, write, and foot up simple addition a year or more ahead of entering school in 1893 at age seven. It was a quasi-public school, financed locally, no county system having yet been organized.”[11]

However, it is not the description that Kartchner gave of his mother but her influence on his life that paints a picture of Annie Hunt Kartchner. As a young teenager, Kenner began playing for dances with Claude Youngblood. Kartchner wrote, “For some time I had ignored mother’s exhortations to stay away from Holbrook, Winslow, Adamana, Navajo, Pinetop, and other dancing communities where liquor was available, this in spite of an unswerving adoration for her at all times.”[12] And Kenner began having authority issues with his father who had returned from a mission. All of the problems came to a head on February 14, 1903, when Kenner, age sixteen, and a friend hopped a freight train without letting anyone know they were leaving home. They worked at various jobs around Flagstaff.

After about four months, Kenner’s father showed up to take him home, and the visit did not go well. First, Orrin demanded that Kenner immediately return to Snowflake with him. Then, Kenner wrote, “Fully aware of my love and respect for Mother, he played up the anxiety and sorrow I was causing her, bringing forth tears I could not restrain. Yet to give in was still unthinkable under the circumstances.”[13] They parted with some bitter words.

A few months later, Kartchner received a message that the Flagstaff postmaster wanted to talk with him. He wrote:

As might have been expected, Mother had written the postmaster to ascertain my whereabouts. . . . He was a kindly man . . . and gave me a good talking to about the debt we owe our devoted mothers. I hadn’t written home in several months, and it’s no wonder Mother was worried. The lump in my throat prevented free conversation for a moment, but I thanked him for his interest, apologized for causing the inquiry, and wound up using his desk to write Mother there and then.

Many a young fellow away from home is remiss in this regard, not from any lack of love and respect for his mother, nor real aversion for writing, but the shabby habit of putting off, of not fully sensing the anguish she is apt to suffer through his negligence. In this instance Mother replied by return mail and was so happy to hear from me that I resolved never to go that long again without writing.[14]

It was still several more months before Kenner Kartchner returned home. One day when he was playing at the saloon in Williams, he noticed his father at the front door. “This time,” Kartchner wrote, “I was really glad he came and told him right off I was ready to go back with him. Homesickness per se has never plagued me greatly, but frequent letters from home since the fall before had kindled a yearning to see the folks, Mother in particular, and whether Dad had come or not, I was ready to pay them a visit. Dad explained that he had not come after me but was in Holbrook and decided to drop out and see how I was getting along. His attitude had changed completely in respect to forcing me home and all was pleasant, as such a reunion should be. Saloon owners, bartenders, and gambler friends were delighted to meet ‘the Kid’s Dad,’ and spoke words of praise that made him feel good, despite his unalterable disagreement with their mode of life and the part I was playing in it.”[15]

After a short delay and many goodbyes, the two boarded the train and started the journey back to Snowflake. Kenner wrote this about the reunion:

That “blood is thicker than water” was never more evident. Nor had I ever realized fully the depth of family ties until that evening when we entered the old house. They are wonderful and should never be allowed to disintegrate. Greetings were accompanied by tears of joy. At supper, Mother and the four kids kept me busy answering questions about the year’s experiences. Some were soft-pedaled to suit the occasion, for saloon life, of all things, was farthest from family tradition and teachings. I was intrigued by changes in my brother and three sisters, how much they had grown in one short year, and how they could play guitars and sing together under Mother’s tutelage. In like manner they marveled at my appearance of maturity. . . . They were eager to hear the old fiddle again, especially the many new tunes I had learned, and thus we celebrated a happy reunion. Jenny was fifteen, Thalia twelve, Lafayette (Lafe) ten, and Leone eight. I was justly proud of them all, clean and sweet youngsters in mind and body [that] only a wonderful mother could produce.[16]

Margaret Jane Casteel Kartchner

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[17]

Maiden Name: Margaret Jane Casteel

Birth: September 1, 1825; Cooper Co., Missouri

Parents: Jacob Israel Casteel and Sarah Nowlin

Marriage: William Decatur Kartchner;[18] March 21, 1844

Children: Sarah Emma (1846), William Ammon (1848), Prudence Jane (1850), John (1851), Mark Elisha (1853), James Peter (1855), Alzada Sophia (1858), Mary Marinda (1860), Nowlin Decatur (1862), Orrin (1864), Euphemia Ardemonia (1867)[19]

Death: August 11, 1881; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Margaret Jane Casteel was born September 1, 1825, in Cooper County, Missouri. Her parents were Jacob Israel Casteel and Sarah Nowlin Casteel. There may have been more than the six children whose names are known, but there were six brothers and sisters at least. Their names were Mary (St. Marie), Emmeline (Savage), Margaret (Kartchner), James, Joshua, and Francis Steven, called Frank, who made a journey down the Missouri River, supposedly to Texas and never returned. His fate was never known, and this was a great cause for mourning by his mother and brothers and sisters.

Margaret Jane Casteel Kartchner. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Margaret Jane Casteel Kartchner. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

The Casteel blood was of French extraction with mixtures of English, Scotch, and Irish. They were evidently of devout Christian faith, for Margaret’s father’s family, consisting of eight brothers and one sister, were given Bible names throughout. They were Abraham, Daniel Benjamin, Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob Israel, Elijah, Mary (md. Daniel Wills—no child), and Charity (md. Zachariah Biddle).[20]

Very little is known of Margaret’s life until she was eighteen years of age, when she married William Decatur Kartchner, on March 21, 1844, in the city of Nauvoo, Illinois. She was a skillful spinner and weaver. One square piece of her homespun cloth is still in the possession of her youngest son, Orin Kartchner. He tells of his brothers shearing their own sheep, and then watching his mother wash each fleece, card, spin, and weave it into cloth.

From any evidence known, Margaret did not have much schooling, but she was a woman of fine intellect and sterling character, modest and refined in manner, and deeply religious. She was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the age of fourteen in Pike County, Illinois.

She and her husband began a westward journey in company with a pioneer group in September 1844, but traveled only as far as Iowa City that year. Then spent the winter there, doing any work possible for means of subsistence, until another start west was made in March 1845.

There was much hardship and short rations of food, and Margaret Jane Kartchner walked for many miles of the journey because she was young and able-bodied. At one time during this hard journey, when their rations had been reduced to one gill of corn a day to the person without salt, they walked in water and mud, shoe-mouth deep, up the Iowa River with no road.[21] Then leaving the river, they turned westward across a large prairie toward the Sioux Indian country.

One day, some Frenchmen and Indians came to their camp and invited them to come and camp near their fort. They pointed to their thin cheeks, realizing how near starvation they were. The Indians gave them dried buffalo meat, which the pioneers thought to be the best thing they had ever tasted. They also brought them roasting ears of corn, and finally a Frenchman, Mr. Henrie, told the young Kartchner that his Indian wife was away and offered them a boarding place if Margaret would do the cooking. They gladly accepted his offer and sincerely appreciated his kindness.

About the middle of July, a chance came to them to go on a steamboat down the Missouri to St. Louis. They decided this was a good move under the circumstances. They had very few possessions to take on board with them, but Mr. Henrie and the Indians prepared two large bundles of dried meat for them. The boatman, seeing their destitute condition, was very kind to them and provided them with food and clothing. A rich French gentleman traveling for his health gave them a pair of blankets and ten dollars in silver, for which they gave him sincere thanks and appreciation.

William D. Kartchner had an older sister living in St. Louis, but she was proud and haughty and considered the young pioneer couple scarcely worth any notice from her. Margaret became seriously ill with intermittent fever, but the sister, Mrs. James Webb, seldom came to see her. However, a Mrs. Powell, wife of a rich southern planter, from whom they had rented a small room, came often and cared for Margaret, administering medicine and attending to her needs. When she was finally out of danger, her husband crossed the river and went on foot sixty miles to see his brother, John Kartchner. He came in his wagon and the young couple ferried their belongings in a skiff across the river, where he gave them a welcome and a comfortable home during the fall and winter of 1845.

William learned of a pioneer company leaving for the Rocky Mountains in the spring of 1846. His determination to join this company greatly annoyed his brother, who had made him fine offers of land if he would stay with him for five years. They finally parted in anger, and William and Margaret Kartchner joined the Mississippi Company in March 1846.

They had hired out to drive a wagon loaded with a thousand pounds of provisions, for a Mr. Crow. They traveled to Fort Pueblo on the Arkansas River by the latter part of July. Here, Mr. Crow broke his obligation, fearing his provisions would run short. This left the young Kartchners again stranded, without even a wagon to camp in. The company had halted here to await instructions from their leader, Brigham Young, and the Kartchners made a camp under a large cottonwood tree, and for a time were at the mercy of kind friends for food. Here, under this cottonwood tree, under these destitute conditions, their baby daughter was born on August 17, 1846, the first white child to be born in the state of Colorado, an honor for which, many years later, that state presented to her, Sarah Emma Kartchner Miller, of Snowflake, Arizona, a gold medal.[22]

Not long after the birth of their daughter, the father obtained work as a blacksmith, in which line he was skilled, at Bent’s Fort, eighty miles down the river.[23] The young wife and child were left to the kindness of a Mrs. Catherine Holladay, and the journey was made on horseback.[24]

The work was heavy, largely consisting of work for U. S. Army troops under General Kearny on their way to the Mexican War.[25] William worked there until late in the fall, thankfully receiving two dollars a day for his labor but was finally stricken with a serious attack of rheumatism and was obliged to return to Pueblo. His wife was often compelled to walk as much as a hundred yards through snow knee-deep to get a cottonwood limb for fuel.

Early in the spring of 1847, they began making preparations to resume their westward journey. With some of the money he had earned they bought an old wagon and provisions, another man of the party permitting them to use a pair of his oxen. William was still unable to walk but did repairing of his own and other men’s wagons by means of his blacksmith tools screwed to his wagon tongue, Margaret carrying the pieces to him which were to be prepared. When they reached Fort Laramie, they learned that they were only three days behind the pioneers under Brigham Young. This company traveled that distance behind them all the rest of the journey, reaching the Great Salt Lake Valley July 27, 1847.[26]

Margaret had another attack of mountain fever but recovered in less time than the year before. They located at a spring about nine miles southeast of the city and began the usual building of an adobe house, fencing, and farming the land allotted to them. Their food was very scarce, but William went once during the winter into the city and bought flour at fifty cents a pound to make bread for their little girl. The parents were without bread of any kind for nearly two months, until new wheat and corn were ripe.

In the winter of 1850, a call was made for a group to colonize San Bernardino, California. The Kartchners and Casteels were among those called to go, and a start was made in March 1851. They remained at San Bernardino until the latter part of 1857, when they were called to return to Utah. The Casteels did not make this sacrifice, and Margaret left her people in California.[27] She settled at Beaver, Utah, with her husband and children.

Another call was given to William Kartchner to help colonize on the Muddy River, a location near the present settlements of Overton and Logandale, Nevada. Margaret and her children followed William there in May 1866, but after several locations were made, and much land cleared and farmed, the settlements were abandoned in February 1871. They now settled at Panguitch, Utah. The hand-planed log house which they built in 1871 is still standing and in good enough repair for a family to be living in it at the present time. William Kartchner was the postmaster of Panguitch, and the hole for the posting of letters is still to be seen, covered with a small board.

Margaret was always busy raising chickens, spinning, weaving, and putting up fruit, both fresh and dried. By this time she had borne ten other children, her family consisting of six sons and five daughters. Two sons and a baby daughter died in infancy. One of the very saddest things in her life occurred at Mojave Crossing, California. Her daughter Alzada Sophia (Palmer) was born January 5, 1858, and the next day, James Peter, just past two years of age, died. Not wishing to bury him on the desert, so far from human habitation, the little body was placed in a metal churn, the lid soldered on, and it was hauled to Parowan, Utah, where it was buried.

In the spring of 1877, William D. Kartchner, sons, and sons-in-law with their families, were called to help in the colonization of the Little Colorado River settlements. Several months were spent in gathering provisions and stock, teams, wagons, and supplies for two years, and on November 15, 1877, they made a start for Arizona. The journey to Sunset covered two months and three days, and Margaret Kartchner was sick most of the time.

The Kartchners settled eighteen miles above Sunset and called their settlement Taylor. But during seven months, no dam was proof against the floods which swept them away as if they were nothing. After five dams had gone out, the entire settlement of Taylor was abandoned, and the Kartchner families moved to the new settlement of Snowflake on Silver Creek, a tributary of the Little Colorado, in August 1878.

Margaret Kartchner had spent thirty-four years of her life in helping to colonize four of the western states. She had walked many weary miles and had journeyed many thousands of miles over mountains and desert, where no roads eased the rocky way, behind slow, plodding oxen, months at a time, having only a wagon-box for her home. Now at last, she had reached a haven of rest, for Snowflake was to be her permanent home. A rather fine log house was built, and life seemed now to have settled into a more peaceful and less strenuous pattern of living. She took part in the activities of the new settlement, especially in the religious affairs.

But the hard years had taken a severe toll, and she lived only three years almost to a day after she began her life in Snowflake. On the morning of August 5, 1881, she was taken with a very bad cough and severe pain in her head. Everything possible was done for her relief, but she grew worse every day until the morning of August 11th, when she passed peacefully away with a pleasant smile on her countenance. Speakers at her funeral dwelt on the upright character and virtuous integrity of this good woman. She had lived only fifty-six years, but her life had been lived to a rich fullness in deeds if not in years.

Ellis and Boone:

When William and Margaret Kartchner joined the Mississippi Saints and spent the winter of 1846 at Pueblo, Colorado, they formed friendships that lasted a lifetime. For example, John Hunt, later bishop of Snowflake, was with the Kartchners at Pueblo, San Bernardino, Beaver, and finally Snowflake. A list of the Mormon Battalion men, women, and children and the Mississippi Saints was compiled shortly after this group reached the Salt Lake Valley; Margaret is listed as twenty-one years old and William as age twenty-seven, a priest.[28]

Thirty years later, when the Kartchner family was called to move to Arizona, William was suffering from rheumatism and Margaret was equally unwell. Grandson Kenner Kartchner wrote that some family members complained about the impending hardships and thought that William might not survive such a trip. William’s reply, according to Kenner, “was to become famous in family tradition, an epitome of his devotion to the religion of his choice. He said, in effect, ‘On the day that they start for Arizona, I shall arise from my bed. I may fall, but I’ll fall with my face toward Arizona!’”[29] As noted here, Margaret, lived only three years after coming to Arizona and was a relatively young fifty-six years old when she passed away.

Anna Dorthea Johnson Kempe

Ellen Greer Rees[30]

Maiden Name: Anna Dorthea Johnson (Jonsdatter)

Birth: February 5, 1837; Glemmen, Ostfold, Norway

Parents: Joen Jensen and Birte Maria Hansdatter

Marriage: Christopher Kempe (Jensen);[31] March 10, 1866

Children: Johanna Christiana Frederika (1867), Betsy Amelia (1868), Amanda Christina (1871), Olena Dorthea (1874), Emma (1876), Ruth Leila (1880)

Death: January 26, 1907; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Anna Dorthea Johnson was born long ago, in 1837 in Norway, the land of the Midnight Sun, the land of fjords, frozen rivers, high mountains, short summers, a beautiful yet stern and hard land where an energetic people have produced a good life, not easy, and it has made a strong and rugged people.

Her folks were fishermen and fished much at night because the fish would bite better then. When she was quite young, she had learned to row a boat well. She made a trip to town alone on an errand, and someone asked her what was the matter with her face. She did not know that she was all broken out with measles. She learned to read, write, knit, sew, and was raised as a Lutheran, the religion then most common in the Scandinavian countries.

Anna Dorthea Johnson Kempe; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Anna Dorthea Johnson Kempe; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

When she was grown, she received a little book containing about twenty-eight Latter-day hymns, some of the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Articles of Faith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As she was very serious and religious at heart, she read and reread the book and was deeply impressed with the spirit and messages it contained. Anxiously, she contacted some of the LDS missionaries and attended their meetings. Soon she knew that they spoke the truth, and she wanted to join the Church.

Her folks did not feel the same, and she was surprised and hurt at their opposition, as they had been so kind and loving before. She felt that she must go on and accept this gospel nevertheless, which she did, though her home and her folks were never the same after that.

After being a “Mormon” for ten years, she was able to emigrate to Utah, a desire she had cherished, though it was hard to leave her beloved country and loved ones even though they had cast her off. She arranged to care for a well-to-do lady on the trip, and the lady would pay her ticket. At Copenhagen, she met a young lady about her age who was to sail in the same company. Her name was Dorthea Johnson, so much like her own name, Anna Dorthea Johnson. They were lifelong friends, though separated later.

The old lady was so disagreeable that Anna had to give up waiting on her. Dorthea, or Thea as she was later called, was sick all the way across the ocean, so Anna got her food. She was used to being on the water and did not get seasick on the trip.

There were 974 souls in that company. It was the largest company that had ever sailed from Europe. John Smith was the captain of the ship, the Monarch of the Sea. The roster of the passengers may be found in British history under date of April 28, 1864, at the Church offices in Salt Lake City. They left Europe April 27, 1864.[32] It was October 5 before they reached Salt Lake City. Anna, with her companion, walked most of the way across the plains. They often went barefooted in order to save their shoes.

Captain John Smith’s Independent Company left Wyoming, Nebraska, in July 1864. On September 2, Captain Smith telegraphed from Deer Creek (411 miles east of Salt Lake City) that he was waiting there with his wagons, having lost twenty head of cattle, and asked that some be sent to help him and his company continue the journey. Through the Deseret News, a request was made that ten or twelve yoke of oxen be sent out to this company immediately. Reports from those able to render assistance were to be sent to the Deseret News office or directly to Brigham Young. Captain John Smith, Presiding Patriarch of the Church, was returning from a mission to Scandinavia, and had crossed the Atlantic Ocean in charge of a large company of Scandinavians on the ship Monarch of the Sea.[33] The largest company over which he acted as captain in crossing the plains arrived in Salt Lake City October 1 or 5, 1864.[34]

They were met on the way by teamsters from Salt Lake City, and at once they began to learn the English language. Anna learned to speak it unusually well. She and Dorthea soon went to live in Provo because they were acquainted with the John Johnson family. Later Dorthea married one of his sons. Anna lived here about three months, and then the missionary whom she had known in Norway, Christopher J. Kempe, came and asked her to marry him. Her friend, Dorthea, was much disturbed. She was not married yet. The two girls were all prepared for housekeeping together. They had gleaned enough wheat for their flour and had stored some food for winter, and had planned to spend winter together.

When she arrived in Salt Lake City, it was polygamy times. It was being practiced with Church sanction. Very soon she and another Norwegian lady, a convert also, Olena (Olina) Oleson Torrosen, were married to a Danish convert and missionary whom they had both known in Norway, Christopher Jensen Kempe.[35]

Then began a life of real pioneering. They were among the early settlers of Provo, living first in a dugout home there. Later her husband built the first brick house there, and it was still standing, not long ago, near the business part of town. Then they moved to Richfield where they were prospering and very satisfied. A Church call came to them to go and help settle and develop Arizona. Many converts were constantly pouring into Utah, and President Brigham Young could see that new places must be found and developed to make homes for the growing population. So this took them far away (leaving their comfortable, new duplex home) to a strange and unsettled country, on the Little Colorado River.

Arriving at Lee’s Ferry, their six wagons with drivers and teams, their stock, and the two families were to be taken across the river on the ferry boats or by swimming the animals. My grandmother, Anna, who had been raised so near the sea, was delighted to see the water and the boats, and her fingers itched until she was in one of the boats with her children to have a ride. She was doing the rowing. (I wonder if she took her five weeks old baby?) Some of the men were pretty skeptical about her adventure, but she was thrilled even when the other wife had hurriedly exclaimed when her children had been invited to go, “No, no, I do not want my children drowned.” So with oars in hand, Anna rowed up to the bend and back down and around and up to the bend again, enjoying it very much and thinking of her beloved homeland.

The first winter in Arizona at St. Johns was pretty hard. Very little food could be obtained. They rationed a little wheat out each day and ground it with a little handmill. Here her husband made one trip into Albuquerque, New Mexico, for supplies and returned with some white flour and other things. Anna made some biscuits with it; the children came in from playing by the river, looked at them, and thought that they were some kind of cake. Her family lived for a time in their wagon boxes, placed low on the ground, combined with some brush sheds. The other wife had two small rooms, and these housed the first LDS Sunday School and day school in St. Johns, Arizona.[36] (Eventually, Christopher Kempe settled with his first family at Concho, but Anna stayed in St. Johns.)

Sunday School was being held one morning; Anna was bathing her young baby, Leila, when the cry of “Fire, fire,” was heard. All the Sunday School rushed out, grabbed buckets or anything that would hold water, then ran to the nearby river and soon had the fire extinguished, but not before it had burned a stack of brush and weeds that was to feed the milk cows during the winter. Some squash or pumpkins were stored in the stack and these were ruined. Her daughter Amelia, who told this, remembered it because her mother cried, and it was very seldom that she cried. Years of privations made for vigorous schooling and even with hardships innumerable, their faith never faltered, and their struggles mellowed them and made them stronger.[37]

Of course, she always had a garden and an orchard when possible. During the growing season, it was a daily task for her to work in the garden. There were weeds to be kept down, ditches for irrigating had to be made, and other tasks. She did not have any sons to share these labors. The fresh vegetables were such an addition to their food supply and so welcome that she did not mind the labor involved.

Her husband loved trees, studied them, and planted different varieties of them wherever he lived. Some real old ones may still be standing in Concho, paying tribute to that noble man.

Fruit was a luxury there in those days. Only on rare and very special occasions were bananas and oranges brought in from the railroad, about sixty miles away. As soon as she could, she had an orchard and different berry bushes, using every inch of space that she had. Like it was yesterday, I remember her early peach tree that had ripe peaches in July. Oh, how eagerly we watched them get ripe. It seemed like they would never ripen, and how good they were! The first fruit they “put up” there for winter was put in cans with a tin lid soldered on with some kind of rosin. They “dried” fruit for winter and found that quite satisfactory, and when they had glass bottles that seemed just perfect. Now we have frozen fruits. What development!

She wanted to go to a funeral. This was in 1888, and it was in Concho about twenty miles away. It was for the two young sons of “Auntie,” the other wife. They had died, two days apart of diphtheria. A neighbor started to take her in his wagon. It was cold and stormy weather. They traveled along, and the downpour of rain became heavier and heavier. All the washes were soon running a torrent. Soon they came to one that was so high that the driver said it was not safe to drive into it. There were big volcanic rocks around there that made it impossible for them to leave the road and hunt a new crossing. The driver suggested that they had better turn back and give up trying to go. “No, no,” she said, “there must be some way to get there.” They decided to ride the horses and leave the wagon there. As she was not used to riding horseback, Mr. Wilhelm tied her feet together under the horse so that she would be less apt to fall if the horse stumbled in a hole, and he tied a quilt around her as it was still raining, and in that way they arrived at the funeral. He led her horse.[38]

One winter, Grandma had three young men, students, boarding with her and her daughter Amelia, who with her three children had lived with her since Amelia’s husband had been killed by lightning. The high school Academy was in her town, so youth from surrounding towns came there for school.[39] The folks of these boys paid for their room and board mostly with produce and some cash. Grandma always had inverted pockets in her long, full skirts. (Styles did not change then as often as they do now.) These pockets held everything from a thimble to a nail and sometimes candy for the children. One time she missed a ten dollar greenback. It was not in the sugar bowl where she kept her money. She hunted for it and worried about it and finally taking Amelia into full confidence, she said, “Melia, do you think that Ira (one of the students) could have taken it?” That was her last hope, and yet she could not believe that he would take it. They decided that she was to talk to him about it. Then she had occasion to get out one of her skirts and clear out the pockets. To her surprise and joy, in the assortment of things was her lost money. She said, “Oh, Melia, I am so glad that I did not speak to Ira.” She was more pleased about that than finding the money.

She kept in touch and was friendly with her folks in Norway by correspondence. They were never baptized into the LDS Church in life. Upon the local settlement of her parents’ property, $100 was sent to her as her share. It came when she needed it so much. “With $80 of it she purchased a sewing machine and the first night that they had it she and her daughters sat up most of the night trying it out, making a dress. For $10 she bought a baby or child’s bed and of course $10 went for tithing.”

She always worked hard but sometimes after she had eaten her noon meal, she would say, “Now, don’t bother me for a few minutes.” Then she would put her bowed head in her hands and say, “Oh, blessed rest,” and for a little time she had well deserved rest as she dozed at the table.

Father Pedro Maria Badilla, see n. 40. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

Father Pedro Maria Badilla, see n. 40. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

The Little Colorado River, which was part of their very sustenance of life, had high periods and low, according to the rainfall. Some seasons it flowed ladylike and gentle, sometimes very low, like a ribbon, and after a heavy storm it could be at flood stage and dangerous. My mother, Anna, with her three children, lived right near it. A flood came one night. Her mother came to help her as my father was out of town. Grandma hurriedly piled flour, sugar, and other foodstuffs high on shelves or on the table. By then, Mother had coats and shoes on the children and they started to walk to a hill nearby. The water was up around the house and steadily rising. Mother said that when the lightning flashed the water looked like a sheet of glass. It was dark and raining and the way irregular with high and low spots. Grandma said later, “I did not know if we would make it without falling, but we did.” They reached high ground and were safe. That house went down, later, in a flood.

This river has brought much havoc and destruction, taking homes, cattle, horses, and many human lives. Its quicksand beds were very dangerous. Stock went there to drink as their only available place to get water and were caught in the sucking sands to die a slow, lingering, starving death. Yet how important [is] this river! It was the settlers’ only source of water until wells were dug (and often these produced no water) or by a rare chance a spring was located. The river supplied their water needs for their stock, gardens, orchards, trees, and mills.

There was a “Father” or “Padre” of the Catholic Church in the town. He needed a new robe. He knew that she did sewing for people and asked her if she would make him a robe. She was used to making nice silk dresses for the Mexican ladies and suits for the men, so she was not afraid to undertake this for the “Father.” But she had not counted on it being so heavy and cumbersome. He was a tall man; it was to be made of heavy cloth, full length, down to the floor, long sleeves, high neck and lined throughout, and, of course, black. It was warm weather; perspiration poured down her face, and her hands were moist as she worked on it. It was very heavy to lift, and she really labored as she finished it, but he was pleased with it, and she had saved him a trip to Albuquerque to get a new one, so she was happy.[40]

She always had a cow or two to provide them with milk and butter (and what buttermilk, oh me, oh my!). She would have felt lost without a cow to milk each morning and evening, and a calf to fatten for beef. She kept some chickens and usually a pig or so to help provide their living. Skunks were prevalent, and they killed and bothered her chickens. She set homemade box traps to catch them, and she caught some, but for the life of me, I cannot find out how she killed them then. Her daughters remember her catching them, but they cannot tell what happened then. Grandma had been through the varied experiences of pioneer life, yet she had not had occasion to handle a gun very much, so I doubt if she shot them, and her neighbors were not “shooting men.” In their own private way these small animals are pretty dangerous for a lady to handle.

She was a good cook, and many a time when I was a little girl, she would send me to take a fragrant dish of soup or pudding to someone who was ill. Need I tell you that I could not resist slipping my finger in and very guiltily and slyly tasting these delicious dishes.

Her mother taught her some of these sayings. She used them often, and her daughters (one of whom was my mother) used them also. In times of discouragement she would say, “Cheer up, this too will pass away.” President Abraham Lincoln had this same motto on a wall in his office. When they were troubled and hardly knew which way to turn she would say, “We see through a glass darkly and the end is not yet.” When it was hard to understand the actions of people and her daughters wanted to criticize them, she would say, “Never criticize the authorities.” Another that she said often was, “Consistency, thou art a jewel.” How true! These sayings helped them over some hard places.

Her strong testimony never wavered; her love for her fellow men grew and grew. She died, having lived happily and with a heart at peace with the world and went to the great beyond to meet her Maker.

Ellis and Boone:

Because Christopher Kempe had two wives, one in St. Johns and one in Concho, he spent time in prison at Detroit, Michigan, with Peter J. Christofferson and Ammon M. Tenney.[41] David K. Udall arrived later and wrote:

We arrived at Detroit at 11:30 p.m. on September 2nd [1885]. . . . About nine a.m. the morning of the 3rd I was taken to the basement and shaved and shingled. I also took a bath and then was given back my garments and given my prison clothes, consisting of hickory shirt, Kentucky jeans, coat, pants and cap; also brogan shoes and cotton socks, all of which appeared to be new. From here I was taken to the shop where Brother Christopherson works. Brother Tenney works in shop B and Brother Kempe in shop C. I recognized Brothers Kempe and Christopherson but mistook another man for Brother Tenney. It was three weeks before we were permitted to meet and converse, as prisoners are not allowed to speak to each other.[42]

A letter published in the Deseret News reported that Kempe and Christofferson were cell mates.[43] One year later, Tenney, Christofferson, and Kempe received a pardon from President Cleveland and were released. The Salt Lake Herald reported that they had been tried for a misdemeanor but sentenced as a felony. They arrived home on October 21, 1886.[44]

Although Christopher Kempe and his two wives worked hard to live polygamy, in death they were separated. Christopher died September 30, 1901, at Concho; Anna died January 26, 1907, at Mesa; and Olena died December 16, 1907, at Pima. Christopher is buried at the Erastus Cemetery in Concho, Anna is buried in the Mesa Cemetery, and Olena is buried in the Thatcher Cemetery.

Olena Olsen Kempe

Autobiography/

Maiden Name: Olena Olsen (Olesdatter)

Birth: May 20, 1843; Solar, Aanas, Glowegian, Norway

Parents: Ole Torsen and Helena Oterson

Marriage: Christopher Kempe (Jensen);[46] December 1865

Children: Joseph Christopher (1866), Hyrum Taraasen (1868), Helena Marie (1870), Nephi Taraasen (1872), Ovidia Serena (1873), Otto Hakan (1876), Eugene Nels (1878), Clara Ingeborg (1880), Charlotte Augusta (1881), Geneva Julia “Jennie” (1884)

Death: December 16, 1907; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Olena Torosen Halversen Olsen, daughter of Ole and Helena Oterson Torsen Olsen, born May 20, 1843, at Solar Aasnas Glowegian, Norway. My brothers and sisters were Halver, Serena, Mathea, and Otto the baby, who died at the age of five leaving me the youngest and the pet of the family. I was baptized into the Lutheran church when a month old and confirmed when sixteen. I went to the priest to be catechized for six months before confirmation. I went to the district school until I was sixteen, then I went to Elbrom where I stayed at a hotel learning to cook for a year. I then went home and stayed until I was eighteen. Then my sister Mathea and I went to Christina to learn the dressmaking trade. We lived with the woman we learned dressmaking from. We went against our parents’ wishes so had to look out for ourselves, and we got into a poor old maid’s home where we hardly got what we wanted to eat. We stayed there the winter, and while there I got a mania for card playing which came very nearly proving my destruction. Every Sunday one of our friends joined us, and we played cards from early till late, just stopping long enough to eat a little. When my father found out about it, he soon stopped it.

Olena Olsen Kempe; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Olena Olsen Kempe; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

After I went home I could not content myself but desired to go back to city life so did not rest until I got back a year later. My parents were very much opposed to it, but I suppose it was to be so because I could not content myself at home. I went to a tailor master in Christiania to learn tailoring. I was there about six months, from fall until spring, when I got dissatisfied again and went to a factory where all kinds of sewing was done, and there I was associated with lots of girls. I was the second-best sewer in the house so got twenty-five cents a day or did sewing by the job.

All the time, I had a desire to see a Mormon, but could get no one to go with me. Finally, I went to their meeting alone, but was afraid to go in so went home. Then a girl friend from home, Nalia Nielsen, called to see me, and I got her to go with me. We stayed a while, and I liked the preaching and wanted to go again. So the next Sunday, I went with a Mormon girl from the factory. Your father [Christopher Kempe] preached, and I thought I never heard the preaching of the Savior before. Then I kept on going (this was in the winter) until spring, when I joined the Church on May 9, 1864, unknown to my parents.

I was baptized by your father. I stayed there until October when my parents wanted me to come home. I hadn’t told them I was a Mormon, and I didn’t want to go home so my mother came for me. I was boarding at a Gentile family’s home who were very bitter against the Mormons. The day Mother came, on Sunday, I was away at a birthday party at a friend’s. She came in about seven o’clock, and I got home at eleven, and during that time they had been telling her horrible Mormon stories until she was nearly beside herself by the time I got home. She wanted me to leave the Church and go home. She made me every promise if I would do so and said if I would I could have all the property and be respected, for she would never tell them I had been a Mormon. I wouldn’t go with her in spite of her heart-bleeding pleadings and with a heart-rending parting; we parted for the last time on earth.

She returned home, and when she got to the harbor, Father met her, and before he got to her, he could see she was bowed down in grief. When she told him of my refusal to come, he got on the next ship and came for me. Two days after Mother left, I was coming home from work at eight o’clock at night when my father met me on the street. He was crazed with grief. He grabbed me by the hand and squeezed it until I thought he would break it. Then he began to rail at me and the Mormons and attracted hundreds around us. He tried to drag me to the police station, but finally I persuaded him to go to the boarding place with me. I was then living with a good Mormon family, but he didn’t know it and none of us told him, so he tried to run down the Mormons to them, but they talked good about them and he quieted down a little after midnight. Then he didn’t dare leave me alone, so he sat up all night and I lay down awhile. Early in the morning, the lady gave him some coffee and cake, and then he said [that] while I packed up to go, he would go out and look around town an hour or so. As soon as he left, a missionary that was boarding there and I went another way, and I ran away to a place six or seven miles from there in the city limits. He was a livery man and a Mormon. I stayed there two days, and the second night he went to singing practice, and there he saw my father and three police men who were searching for me, so he said I could stay there no longer, so at four o’clock (nights in Norway are light at that time) I got up and left there. We went to several places to try to find lodgment, but they all advised me to go on. As I left each place, about five minutes after [later] Father and the police would come searching, but I just missed them each time. The missionary and I walked on to a place four miles away, and we stayed there guarding the place for three days. Every harbor and depot was guarded as I left this place at one o’clock at night and rode twenty miles out to Drobak where I took the steamer for Copenhagen. I arrived at Copenhagen without a friend and no money, but I had the address of the mission president. He was not at home, and the office men received me very coldly. Sister Leigburg came while I was there, and she took me home to live with her. I went with her to a cape factory and there got work at twenty-five cents a day. I stayed there until spring. I wrote home often sending my letters through the mission house at Christiania [Oslo]. Mother sent my grandmother’s feather bed and a few clothes by some of the emigrants. On the 1st of May, I left with eleven hundred emigrants from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany—among them your father and his wife.[47] When we had been out two weeks, she took sick with smallpox, and I waited on her night and day for four or five weeks. She died in Quincy, Illinois, and was buried there.[48] —Written [down] in 1939 by Charlotte Mangum. (The following was added by her daughter, Charlotte Mangum.)

The journey across the plains was a hard one, as Father and Mother walked every step of the way. After arriving in Salt Lake City in 1864, Mother worked about from house to house for several months, and then Father persuaded her to marry him. They had been married but three months when Father decided to take another wife which, of course, was an awful trial, though I think they got along well and certainly trained their children to love half sisters or brothers. Mother plied her trade of tailor in Salt Lake as elsewhere, always having the name of the best seamstress of any.

After a few months, they were called to Provo, and there Auntie went to the farm on the bench to live and mother lived in town. They lived here three years, and Lena, Hyrum, and Nephi were born. They built some of the best homes in Provo—Mother and Auntie sewing for the money—Father doing the work. In 1872, they were called to give up their homes and move to Richfield. Here, once again, Auntie lived on the farm, mother in town supporting, or practically supporting, her family with sewing, but here, as everywhere, having the name of being the best-dressed woman in town. Joe’s first baby dress was one mass of eyelet embroidery tucks and ruffles—all done by hand and beautiful, and it was by no means his only dress—sweeping the floor as he sat in his mother’s arms. A baby’s dress at this time was usually 1½ to 2 yards long. Mother spun her own yarn for many years for booties and stockings.

Not only did Mother keep an immaculate house, but she sewed for others almost all the time, did all the milking of cows until the children grew old enough, worked in the field like a man, and yet radiated sunshine. I was told by a friend of hers that she never saw a time when she couldn’t have sat on the floor and eaten from it, knowing it to be as clean as most people’s table.

She buried Hyrum in Provo and Nephi and Clara in Richfield. In Richfield once more, Mother and Auntie scrimped and saved, and Father built them at that time the finest homes in town, but they didn’t get to enjoy them, for once more Father got an idea that to get to Jackson County, he had to make the horseshoe curve by going though Arizona into Mexico and out into Jackson County.[49] So this time he asked for a call, which Mother and Auntie considered genuine, so once more they sacrificed all they had and came to Arizona arriving here in October 1880. No houses—no shelter—and winter coming on. Father finally found an empty Mexican house which had been used for a chicken coop into which we moved. He built a picket house for Auntie out on the farm, and so we tried to live. With flour $12 a barrel—no money and no work—the family almost starved, finally getting down to cane-seed mush. They ground the cane-seed on the coffee mill and cooked it. It was extremely unpalatable but wholesome, so the kids all thrived on it. But poor Mother in her delicate condition couldn’t stand the smell of it so had an awful time. She saved and sewed and got flour enough to make a little gravy each day, and for weeks that was the way they lived until finally the flour ran out, and the day before I was born (April 18, 1881), mother didn’t eat a bite.

The morning of my birth she arose, shook the flour sack, and made a small bowl of gravy. Before she could get the children around the table, she took sick, rustled the babies off to the neighbors saying, “Don’t tell anyone you haven’t had breakfast.” She covered the table with a white cloth and went to bed. When I was dressed and laid beside her, the midwife went, little knowing mother had not a bite to eat, for the children rushed home and devoured everything in sight. A short time later a neighbor, a Jewess, Mrs. Nathan [Pauline] Barth, and our savior, called with a tray of food. Mamma said, “Set it on the corner of the table.” But Mrs. Barth said, “Oh, no, this is for you.” Mamma began to cry and said, “How can I eat and my children starving?” Mrs. Barth said, “Your children shall be fed but not until you eat every bit on this tray.” She told me Mother ate like a hungry beast and sobbed like a baby. Then she [Mrs. Barth] took the children home [and fed them], and I was twelve years old when she needed a girl and from then on we never went hungry.

Olena Olsen Kempe with unidentified children or grandchildren; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Olena Olsen Kempe with unidentified children or grandchildren; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

When we had lived in St. Johns three years, Father was called to Alpine or Bush Valley, as it was then called. Auntie refused to leave St. Johns, so Mother pulled up once more and moved. Shortly afterwards, Father was sent to Detroit to the Federal Prison for polygamy, and we once more had a terrible time—poverty, cold, suffering—three years of it. Father was in prison eighteen months then returned, and three years later he was called to be bishop of Concho. From then on life was easier—more sewing for the Mexicans, and the little store we had was quite profitable. Mother was fairly happy though crushed and broken when in December 1889, Otto and Eugene, eleven and thirteen years of age, died and were buried in one grave.[50]

The whole family was down with diphtheria except me, and I took it when I jumped into Otto’s coffin, wound myself around him and refused to let him be buried without me. Oh, such a life! Many a time when we children couldn’t find the cows, we have known her to be out until twelve and one o’clock hunting for them. I can scarcely remember her going to bed at any time before one or two and up at five—so much to be done—so many Mexican dresses to make—boarders to cook for—visitors to entertain, for no one went through Concho from Salt Lake City to Mexico who did not stop at Bishop Kempe’s. If Mormons—no pay. We did have the joy of entertaining nearly every Apostle and President of the Church—privilege few Church members ever had.

Mother was president of the Primary ten years and hardly missed a Primary in all these years. Only once do I remember one when she was sewing a wedding dress for a Mexican who was to be married at nine o’clock the next morning but was coming for the dress that night. Primary time came and mother said, “I haven’t got this dress finished, so tell my counselors I can’t come to Primary though I expect I’ll be sorry.” So I ran to the counselors, who neither one could go, and back to Mama I went, who said, “Well, you’ll just have to go and hold Primary for me.” This I did though only about twelve years old. That night at eleven, Mother went to press the dress and found the under-arm gores wrong side out.[51] The poor dear just broke down and cried and said, “Oh, if I had only gone to Primary this would never have happened. Don’t you ever let work keep you from your church duties.”

When Mama resigned from her position as president of Primary, we had a surprise [for] her, which was the grandest occasion ever held in Concho. Every man, woman, and child in town was there, and each child in Primary brought her a quilt block with his name and age on it. I’ll never forget that time—supper and all. Mama, being president, gave me many opportunities—among them the privilege of taking part, reciting, or speaking in nearly every stake conference, and was she proud to have me do so!

She took in sewing enough to send Joe on a mission and was so proud of her missionary boy. While he was in Norway, Mama got some money from her estate (at the time she joined the Church her father disowned her and cut her off without a cent, but at this time her brother and sister relented and sent her several hundred dollars). She paid some on the place, bought us an organ, and had enough to send Joe to gather some 300 names and bring home a wife. Mother’s mother mourned herself to death over Mama joining the Church and her father soon followed, which always made Mama feel she was responsible for their deaths.

When Joe got home and found time he could leave for a while, [it was decided that we would go to Salt Lake City.][52] Mother furnished all expenses; Joe [furnished] the team and wagon, and in company with Brother and Sister Pulsipher and a part of their family, Mother, Jennie and I, Joe [and his wife] Lauretta [and their two children] Odelia and Otto went [on] that long, old, hard wagon trail to Salt Lake City, Utah, to do temple work for the names Joe had collected.[53] We were a month each way on the road and spent three weeks in Salt Lake City, a trip never to be forgotten by Jennie and me. Naturally with our food, bedding, and clothes, all of us could never ride at once, so Mother walked nearly every step of the way. Oh, what she sacrificed for the Church! Never complaining, but always planning something more to do. Jennie and I missed three months of a six-month school, but it was well worth it. Our trip was worth ten times the schooling.

Father’s store became prosperous enough that they were able to build the nicest house in town. Mother kept it so neat that it seemed a palace and was a home to everyone.

In August 1898, Mother sent me to school at Provo. Father went to Norway on a mission in December. In June of 1899, Mother came to join me and keep Jennie and me in school by keeping boarders, a happy year. In June, Mother and I came on home, and Jennie stayed another year in Provo. I taught school and paid Jennie’s way, so Mother had the easiest year of her life and from then on I turned over to her every cent of my wages, and she bought my clothes and kept the rest. Jennie and Papa came home in June. In September of 1901, Dad was run over by a runaway team and a load of hay and died two weeks later. In the following April, Jennie died, eighteen years old. This nearly killed Mother.

In August, I came down to Pima to teach school, and Mother joined me in November and for three years really enjoyed life and visiting old friends. In June 1905, [James] Harvey [Mangum] and I went to Salt Lake City to be married and then joined Mother at Concho. We lived with her until the next August. Otto [Kempe Mangum] was born in July, and Mama was so proud to name him. In October, Mama joined us at Pima but was only with us until November. She took sick and died December 16, 1907.

Ellis and Boone:

As noted in this sketch, Olena Kempe lost two of her boys to diphtheria, and then her daughter Jennie died at age eighteen. Jennie’s death had an interesting outcome as told in the memoirs of James Warren LeSueur.[54]

In January of 1898, James W. LeSueur of Apache County left for a mission to Great Britain. At the end of his mission, he was given permission to go to the Isles of Jersey and Guernsey to gather genealogical information and to preach to his relatives. While there, he got a telegram informing him that his brother Frank had been killed by outlaws near St. Johns and that he was to return to Arizona.[55] He wrote, “When I came home from my mission I missed my brother Frank very much. He and I had been like Jonathan and David in our love and companionship. I did want to see him again, and had a feeling that I would do so.”[56]

Shortly thereafter, James and his father went into the White Mountains to visit some sheep camps. All of the herders extolled Frank’s virtues and expressed their sympathy. James wrote, “When night came we made our bed under the pines and Father retired. I went out a short distance and engaged in prayer. I told the Lord that Father and I felt that Frank had been with us during the day on our trips to the various camps and that I knew he was not far away and wanted to see him in the work he was called to do. I had full faith that my prayer would be answered.”[57]

Later that night, his prayer was answered and James saw his brother preaching to relatives in the spirit world. Frank was assisted by a young relative who had died recently, and James also saw another young woman who was to be Frank’s wife. In his memoirs, James wrote, “Who was the young lady at the door? As I described her to my mother she declared her to be my cousin Nellie OdeKirk, who was thrown off a horse in Vernal, Utah, and her foot caught in the saddle . . . . When the horse stopped she was dead.”[58] Then James LeSueur told about the other young woman he saw:

A short time after this a young lady’s mother came from Concho (Sister C. I. [Olena] Kempe) who said her daughter Jennie had died recently and at her death bed called her mother and asked her to go to St. Johns and ask my parents consent to have her sealed to Frank LeSueur. She told her mother that Frank’s spirit had appealed [appeared] to her and told her that he loved her and wanted her for his wife and needed her in the spirit world. That she accepted his proposal. Then he told her she would die soon but for her to ask her mother to ask my parents to have the sealing as wife to husband attended to in the temple for them.

My parents called me in and I asked if she [Sis. Kempe] had her picture. She produced it and it was the photo of the young lady who was “to be Frank’s wife.”[59]

Sometime later, the sealing of Jennie Kempe to Frank LeSueur was done in the Salt Lake Temple. James LeSueur then married and moved to Mesa in 1906. He was president of the Maricopa Stake during the time the Arizona Temple was being built, and he was called to be part of the temple presidency. LeSueur wrote, “Why I should have been given such a grand vision. . . . Without this vision I doubt if I would have been half as zealous or had the courage to [gather genealogy] and work for a temple.”[60] This vision and this sealing were also a comfort for Olena Kempe after the death of her daughter.

Note: For all of the problems with moving a Scandinavian name into American English, see Olena Olsen Kempe, KWJZ-FM3, at FamilySearch.org.

Sarah Jane Curtis Kempton

Unidentified Son or Daughter

Maiden Name: Sarah Jane Curtis

Birth: September 28, 1847; Keg Creek, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa

Parents: Joseph Curtis and Sarah Ann Reed

Marriage: Alvin Bradford Kempton;[61] January 1, 1868

Children: Alvin Joseph (1869), Richard Hyrum (1871), Asa Bradford (1873), Zetta Jane (1875), Eliza Anna (1877), Delia Caroline (1881), Laura Sophronia (1884), Zilpha Miriam (1887), Heber Curtis (1890), Calvin Ira (1893)

Death: July 12, 1939; Eden, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Eden, Graham Co., Arizona

Sarah Jane Curtis was born September 28, 1847, at Keg Creek, Pottawattamie County, Iowa, to Joseph Curtis and Sarah Ann Reed. She was the oldest of eight children, so found plenty to do in the house, also helping with the outside chores.

Sarah Jane only had the privilege of attending school six months in her life. However, being a studious child, she learned to read and write and also did quite well in arithmetic. While a girl at home, she did most of the family sewing. Many times she helped shear the sheep, spin the yarn, weave the cloth, and make the dresses.

At the age of twenty, she met a young man, Alvin Bradford Kempton, whom she fell in love with. After a very short courtship, they were married at Payson, Utah, January 1, 1868. From Payson they moved to Salem and from there to Burrville, Utah.

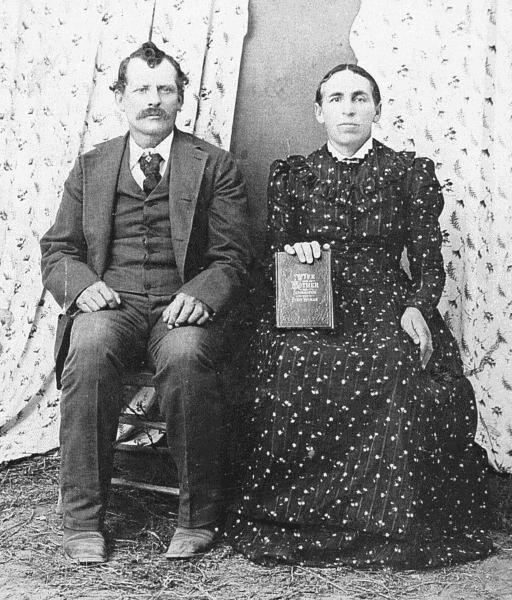

Alvin Bradford and Sarah Jane Curtis Kempton; Sarah is holding the book Wife and Mother: Inspiration for Every Woman. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

Alvin Bradford and Sarah Jane Curtis Kempton; Sarah is holding the book Wife and Mother: Inspiration for Every Woman. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

While living in Burrville, many of their relatives and friends were moving to Arizona, so this good family decided to make the move at this time. The family consisted of father, mother, three boys, and two girls.

After bidding fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, relatives, and friends goodbye, they started to Arizona in a covered wagon. It was a long hard trip. They spent two years on the way, as in Northern Arizona there was a railroad being built so Father spent sometime working on it.[62]

The Apache Indians were on the warpath at this time. As they were traveling along, two Indian men on horses rode up to the side of the wagon and said “Stop,” so Father stopped. One of the Indians asked, “Have you got a gun?” Father said, “Yes.” The Indian said, “Let me see it,” so Father handed him the shotgun. The Indian took it and looked it over, then handed it back and said, “No good.” Then rode away. Mother was very frightened and glad to see them ride off.

They traveled on for a few more days and finally arrived at Pima, Graham County, Arizona, where they lived a few years. At this time there were three boys and three girls in the family. Sadness came into the family as two of the little girls, one eight and the other three years old, passed away of diphtheria just five days apart.[63] They were buried in the Pima Cemetery.

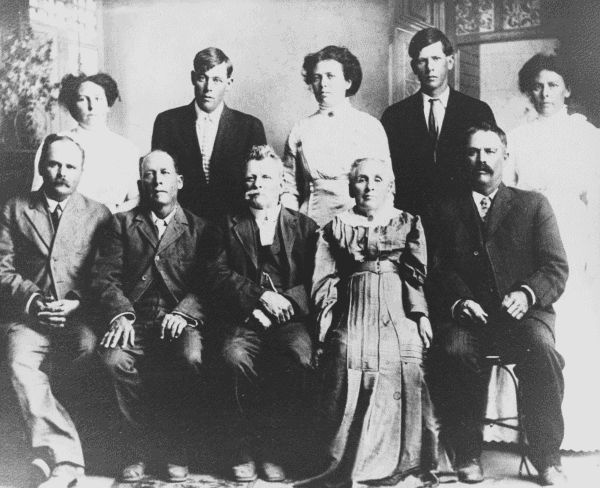

Alvin and Sarah Kempton family; front (left to right), Asa, Dick, Alvin, Sarah, Jorde; back, Laura, Heber, Zilpha, Cal, and Annie. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

Alvin and Sarah Kempton family; front (left to right), Asa, Dick, Alvin, Sarah, Jorde; back, Laura, Heber, Zilpha, Cal, and Annie. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

Not long after this happened, the family moved across the Gila River to a town that was afterwards called Eden.[64] At Eden four more children were born making a family of ten.

Mother was a true Latter-day Saint woman, always ready and willing to work in the Church. She worked in the Primary, Sunday School, YWMIA, and the Relief Society.

Mother lived to be nearly ninety-two years old. She passed away July 12, 1939, at her home in Eden, was buried on July 13, 1939, in the Eden Cemetery after a long and useful life.

Ellis and Boone:

The railroad that the Kemptons stopped to work on was the Atlantic and Pacific, later known as the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. It followed the Amiel Whipple survey route of 1853, and the towns of Holbrook, Winslow, Flagstaff, Williams, and Ash Fork sprang up along its route.[65] Many of the Mormon men found supplemental work using their teams and scrapers to build the railroad grade. John W. Young, Jesse N. Smith, and Ammon M. Tenney secured the first contract in 1880 for a section about 150 miles northeast of Snowflake. They also arranged for food supplies to be sent from Albuquerque to the hungry settlers.[66]