I

Esther Isaacson Rogers, "I," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 305-312.

Elsina Peterson Isaacson

Esther Isaacson Rogers[1]

Maiden Name: Elsina “Sina” Peterson

Birth: July 9, 1865; Gunnison, Sanpete Co., Utah

Parents: Thomas Peter Peterson (Anderson) and Maria (Mary) Tyggeson (Christensen)

Marriage: Isaac Isaacson; September 25, 1882

Children: Elizabeth (1883), Ella Elsina (1885), Isaac (1887), Natalia (1889), Archibald (1891), Florence (1893), Peter Martin (1895), Thomas (1898), Esther (1900), Maud (1902), Andrew (1904), Paul (1909)

Death: November 20, 1944; St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Elsina Peterson Isaacson was born at Gunnison, Utah, July 9, 1865, the third child born to Thomas Peter Peterson and Maria Tyggeson. Her father and mother came across the plains to Salt Lake City in 1859.[2] They were both in the same company crossing the plains by ox team. Here they became acquainted and their courtship was started. After their arrival in Salt Lake, they grew more fond of each other and soon they were married. Then they moved to Ephraim, Utah, where they were living when their oldest child, Mary, was born July 24, 1861.

On March 15, 1863, their second child, Thomas, was born, also in Ephraim. After a time they moved to Gunnison, Utah, where Elsina was born July 9, 1865. In the year 1867 another boy was born. He was named Joseph. He died in infancy. Somehow the month and day of his birth was not shown on the family record. Neither was the date of his death. It may have been that at the time of his birth his father had to be away most of the time, as the people were having a lot of trouble with the Indians and he was called to help protect the settlers. And since he was the record keeper of the family, it seems from seeing some of his books that this was perhaps the reason that these dates were not on the family record.

In the year 1867, Elsina’s mother and father received their endowments in the Salt Lake Endowment House. So Mary, Thomas, and Elsina were sealed to their parents because they were born before their mother and father were endowed and sealed to each other.[3]

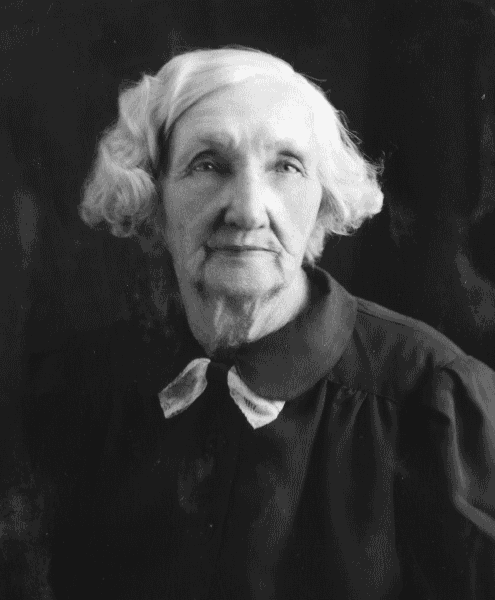

Elsina Peterson Isaacson; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Elsina Peterson Isaacson; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

On September 24, 1870, also in Gunnison, their fifth child was born. He was given the name of Andrew Christian Peterson. When Elsina was four years old, they moved to Richfield. They moved three times in one year because of the Indians.

They lived in Richfield several years, and then one day a very sad thing happened. On May 29, 1873, Elsina’s father was killed. He was helping plow a big public canal, and when he got between the cattle to fix the chains on the plow, they became frightened and ran. The plow cut a big artery in his leg, and for lack of someone knowing how to stop the bleeding, he soon bled to death.

This was a terrible shock to Elsina’s mother and the children also. Sister Peterson was confined to her bed for a time and was threatened with a nervous breakdown, but through faith and prayers her hope came back again, and she recovered her health and began living again with her children, giving them aid and comfort.

Elsina was seven years of age at the time of her father’s death. Shortly after this, the United Order was started at Richfield. Her mother put all her cows and everything else she had in the Order. They stayed in Richfield until the spring of 1878. When the Order broke up, her animals and other things were given back to her.

Very soon after the Order broke up, Sister Peterson’s husband came to her three nights in succession and told her to take her children and go south. She told him it was too stormy. He told her not to worry about that but that the south would soon become fertile. It worried Elsina’s mother a great deal, but she soon decided she had better go. So she began preparing for the trip. She sold everything she had but a few things and a few animals she was going to take with her.

Sister Peterson, being a widow, had a hard time getting everything ready to go. She had some old friends who wanted to help her out and who were going in a small company a few days ahead of them. This small company was made up of John Anderson and his wife and Mr. Trejo and his wife.[4]

Sister Anderson had no children of her own and Elsina had helped her some, and she was very fond of her. She pleaded with Elsina’s mother to let her go with them as they would soon be coming and it would be only a short time that they would be separated.

She finally consented to let Elsina go with them if they would take her brother Tom also. Tom was anxious to go for the adventure. Elsina’s mother also thought it would help them in traveling to lighten the load and that it would not be for long.

This small company now consisted of John Anderson and wife, and Mr. Trejo and wife, and Elsina Peterson, who was then twelve years of age, and her brother Thomas, who was then fourteen years of age.

This Brother Trejo was a pure Castilian Spaniard of light complexion. He had a very long red beard. He was also well educated. Mr. Trejo was the Spaniard who translated the Book of Mormon into the Spanish language while he was in Salt Lake City. He and his wife had a light wagon and a horse and a mule for his team. They also brought four chickens along with his other livestock.

John Anderson and his wife had a small bunch of cattle, two wagons and two yoke of oxen, one of which he had given five acres of land for. He also had six head of horses which Tom Peterson drove along with his yoke of cattle and Elsina’s cow which her mother had sent along with them to sell whenever they needed to.

They prepared for weeks for this trip. They baked three bushels of crackers and a lot of zwieback.[5] They boiled down several gallons of cream and sugar so it would keep. They also took along an eighty-gallon barrel of cured meat. Among other things was a large churn of preserves they took along so they could have the churn when they got to Arizona.

The one wagon of Mr. Anderson’s was loaded to the bed with flour, and her brother Tom and John Anderson made their bed on top of this wagon, while Mrs. Anderson and Elsina made their bed on the other wagon. Mr. Trejo and wife also made their bed on top of their wagon load of provisions.

It was just two weeks before Christmas when they left Richfield and started on their long journey. It was very cold, and the ground was white with a foot of snow. They traveled for two weeks before they arrived at St. George, where they stopped for ten days and did temple work.

After they left St. George, they had a terrible time crossing the Rio Virgin and Santa Clara Rivers, for there was so much quicksand. They had to unhook the teams and ride the horses and then go back for the wagons because they were afraid of them sinking as they were so heavy. But they had the help of the Lord with them and made it across without any serious trouble.

That night they camped with some Mormon ranchers. These were the last white people they saw until they finally reached Pearce’s Ferry. Here Mr. Harrison Pearce was very glad to see them. He told them he hadn’t seen a white person for three months. He came over in a boat to talk to them and that night Elsina’s brother Tom slept with Mr. Pearce in his boat. The next morning he brought over a larger boat and ferried their wagons across the river. The cattle were made to swim the river.

After this ordeal, they went on their way making about five to seven miles per day on the dry plains of Arizona. They had a little guide book they consulted often. In looking at this, they found their next long stop was at Iron Springs (which is now a beautiful resort).[6] There they stopped two weeks to rest and doctor their cattle for what they called “holler horn.”[7]

After this much needed rest, they began their journey again toward Walapai Desert.[8] They traveled for many days never seeing anyone but Indians until they reached the desert.

Here they met a young man who came from Leeds, Utah (or Dixie Country, called Silver Bluff). He wanted to trade horses. He had taken a load of men to the silver mine and wanted a fresh fast horse to get out of this “God forsaken country” as he called it. So they traded horses. The horse they traded for was a high-spirited “roan.” He proved to be a blessing to them when they landed on the San Pedro River. He would never allow a Mexican or an Indian to come anywhere near the herd. This they did many times when they came to steal horses.

When they did come, this horse would go around and around the herd snorting and bucking, causing them to stampede and run away until all signs of danger were over. Then he would bring the herd back near camp.

The old horse they traded for the “roan” was over twenty years old. President Thurber had used him on his mission to the Indians.[9] When the man who traded for him went through St. George, he lost him there but finally found him in his old stall with the Thurber family all rejoicing to see him again and wondering where he came from.

Elsina Peterson Isaacson with family. Seated, left to right, Isaac Jr., husband Isaac Sr., Elsina, Peter; standing, Arch, Maud, Ella, Esther, Natalia, Florence, and Andy. Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Elsina Peterson Isaacson with family. Seated, left to right, Isaac Jr., husband Isaac Sr., Elsina, Peter; standing, Arch, Maud, Ella, Esther, Natalia, Florence, and Andy. Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

After reaching the Walapai Desert they again consulted their little guide book which told them that when they reached there, they should turn and drive to the left of the road and they would find water in a canyon. This they did and found the water, which was very fortunate as their cattle had been bawling for water and their tongues were hanging out.

This water didn’t help for long as they were dry again when they got down the canyon. But they continued on toward Hackberry. By the time they reached there the cattle and oxen all had their tongues hanging out and were bawling for water worse than ever. At times it looked like they would all perish for the lack of water.

Neither Brothers Anderson nor Trejo had had any experience under such conditions. That they survived this trip was thought to be a miracle by others who had had similar experiences. But the blessings of the Lord seemed to be with them.

They stopped at Hackberry for five days to rest their tired animals. Three of these days were spent in baking bread, which they sold to the Government Indian Scouts. The camp at Hackberry had been out of flour for a week when they reached there.

While at Hackberry, they were happily surprised to run into two Mormon families. One was a Mr. Edward E. Jones, and [another was] a son of President Heber C. Kimball, David Patten Kimball.[10] They were freighting to get supplies so they could go on to the Gila Valley.[11]

After they left Hackberry, they traveled for weeks and finally came to beautiful cedar country. It was now spring, and the snow was melting. They got lost because the cedars were so thick and the tracks made in the frozen snow were disappearing. They traveled for three days on the wrong road. Then they happened to run into a copper mine, and there was a white man there who told them how to get back in the right road. They averaged only five to nine miles a day.

They continued on and finally reached the Salt River Valley where Phoenix now stands. Here they found red clover a foot high in the few streets that were there. This made it hard for them to drive their cattle as the cattle wanted to stop and eat.

The population of Phoenix at that time was mostly Chinese and Mexican.[12] They camped in the Phoenix area one night and went on the next day up the Salt River where the old canal took water out of the river. Here they were asked to stop and help work on the canal as they were anxious to complete it so they could irrigate the land in the valley. So they stopped and worked here for two weeks.

From here they went on up the Salt River and through the Gila Valley, where they only saw a few Indians. Then they continued on through Tucson where there was only one street of any length. From Tucson they traveled over a hundred miles up the San Pedro River and on to a little fort called Philemon Merrill’s Camp, which is at present called St. David, Arizona.[13]

It took them three weeks to get to this camp from the valley. They all lived here for some months and were very welcome when they first arrived with all their animals as the Mexicans had stolen every animal but one old mule and had run them into Sonora, Mexico.

It wasn’t long until John Anderson and his wife and Elsina and her brother Tom moved ten miles below this camp where they farmed for a German sheepman by the name of Hornsogle.[14]

At one time during this summer, they had rain for ten days and nights, washing all the crops away as the San Pedro was five miles wide at this place. Here the freighters also crossed.

Among some of the people coming here to cross the river and having to remain over night with them was ex-governor Anson P. K. Safford of Arizona Territory. He had two other men with him by the names of Stowe and Layfette from New York. Ex-governor Safford was taking these men to see some gold mines in the Huachuca Mountains.[15] President Porfirio Díaz and family of Old Mexico also stopped over night with them on his way to Tucson, Arizona.[16]

It was while John Anderson and wife and Elsina and Tom Peterson were living and working in Hornsogle Farm that their tent caught fire, and they lost almost everything they had. Among the things lost in the fire were Elsina’s new trunk and dresses, three new pairs of shoes, and a nice feather mattress that her mother had sent with her, along with other precious articles and keepsakes.

After this, the Andersons took their wagons and cattle and went back to the Salt River Valley with Elsina and Tom Peterson going with them. After they got back to the Valley, they stopped near the Hayden Mills. While here, Mr. Charles T. Hayden, who was Senator Carl Hayden’s father, heard about their fire and how they had lost almost everything they had.[17] So he gave them some flour and other provisions which helped them out greatly as they were almost destitute now. I have heard my mother Elsina Peterson tell about this many times. She always had a warm spot in her heart for the Haydens.

Mr. Trejo and wife did not return to the Salt River Valley but remained at St. David. He was a faithful Latter-day Saint, and his posterity is still in St. David.

When John Anderson and wife and Elsina and Tom got back to the Salt River Valley, the town of Mesa was laid out and had water running on the land. It was taken out of the canal that they had stopped and worked on months before.

Another thing that had been developed while they were gone was the manufacturing of brown sugar. This was the first in this country and perhaps the first in the western states. This was developed by George Crismon who sent back East for his cane seed to plant and for the machine to make the sugar.

After coming back to Mesa, Mr. Anderson put in a crop here. Elsina Peterson stayed on with the Andersons in the valley. Her brother Tom stayed for a while, and then he drove a herd of cattle for a Perkins family who were moving to the Brigham City fort, which is now Winslow, Arizona.

When he reached there with the Perkins family and they didn’t have Elsina with them, Sister Peterson, his mother, was very much upset about it as it seemed she would never get Elsina back home again.

Finally Charley Curtis, a very kindhearted man, volunteered to go to Mesa and get Elsina. Her brother Tom went with Brother Curtis to Mesa to get her, and they traveled in a buckboard. It was a very sturdy vehicle but not much for comfort. They had to sleep on the ground. They finally returned with Sina, as they always called her, to Brigham City (Winslow) on April 20, 1880.[18]

Elsina was thirteen years old when she last saw her mother and now she was fifteen years of age. It had been two long, hard years to be away from her mother and other brother Andrew and sister Mary. What a happy family they were when she returned to them healthy and strong and they were together again. Sister Peterson always appreciated more than words could express the kindness of Brother Curtis at this time. She felt that her prayers had been answered.

After Sister Peterson got her family back together once more, they continued to live in the Order for a year. Here Elsina took her mother’s place working in the kitchen as all the women did.

In 1880 the Order began to break up, so Sister Peterson drew out of the Order and joined the Overson family and the Peter Isaacson family. There were only three families in this company of trail wagons. Brother Isaacson had horses and mule teams. The Oversons and Sister Peterson’s family had ox teams, but they all traveled together. When they reached The Meadows, Brother Isaacson’s family and Sister Peterson’s family decided to stay there.[19] The Oversons decided to go on to St. Johns, Arizona.

At this time there were only three families at The Meadows. They were Erastus S. Wakefield, Joseph Buck Wakefield, and Polish Lambson and their families.[20]

Brother Peter Isaacson and Tom Peterson worked together building log houses while they were camped in their wagons and wagon boxes. They were able to get logs from Green’s Peak in the White Mountains some thirty-five miles away. They chopped down logs and hewed them, loaded them on their wagons, and brought them down to where they built the log cabins. The roofs were made of small poles hauled down from the mountains also. After the poles were put on for the roof, they were covered with a layer of mud and then plenty of dirt was put on top until it would keep the rain out. The floors consisted of dirt as there was no lumber to be had. Martin Isaacson and Andrew Peterson took care of the cows by herding them so they wouldn’t get lost while the others were working on the houses. Later Isaac Isaacson, son of Peter Isaacson, who had been in Ephraim trying to take care of his father’s farm or sell it, joined his parents at The Meadows.

The first year, 1880 to 1881, was a very hard one. The first land that was cultivated by these settlers was fenced and the sage brush that covered it was grubbed off, which was a real job. The first fenced field was called “the little field.” It was located across the river east of where the houses were built. This field was divided into ten-acre lots. Each one drew a number for the lot they were to have. They were all planted into wheat, corn, and gardens. The wheat came up beautifully and was making rapid growth when all at once the grasshoppers landed and cleared the wheat fields bare.

The poor settlers felt very discouraged and had to go elsewhere for work. At this time the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Companies were building a railroad from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Los Angeles. (This railroad was later sold to the Santa Fe Railroad.) So, most of the men went to the railroad for work. Among those going off to work were Isaac Isaacson, who had recently come from Ephraim, and Elsina’s brother Tom Peterson.

Ike Isaacson took his horses and part of his father’s horses and fitted out a freight (team) outfit. Tom Peterson took his mother’s ox teams and wagons, and they both went to the railroad for work. They later separated and after some months Isaac returned and Tom went on to Flagstaff. During Tom’s absence, he was unable to send his mother any money which made it hard for her. But she did have her own cows and chickens. And with the help of others she was able to grow a garden. Elsina also contributed to their support from the work she had with Bishop David K. Udall for about ten months at this time. She said it was a hard pull for them, but they never went hungry and always had clothes and shoes to wear.

Elsina had met Isaac Isaacson before he went off to work on the railroad, but it was after he returned from working on the railroad that they decided to get married. They had to travel all the way to St. George, Utah, by horse team and were married in the St. George Temple on September 25, 1882.

After their marriage, Elsina and Isaac lived in the E. S. Wakefield home which they purchased from him at The Meadows. Here, a year later, their first child Elizabeth was born. She died later the same day on account of no doctor to care for her right at birth. This was a crushing blow to her parents. She was taken to St. Johns cemetery and buried, as there was no cemetery at The Meadows.

After a few years, they had two more children born at The Meadows. Then they moved to St. Johns where the children went to school. They returned to The Meadows for a few summers, but it wasn’t long until they moved to St. Johns completely. They had twelve children in all. They also lost their last boy who was two years old with typhoid-pneumonia, which was another sad occasion.

At the time of Elsina Peterson Isaacson’s death, which was November 20, 1944, she had a family of six boys and six girls, ten of whom were living. She also had thirty-seven grandchildren, eight of whom were in the Armed Forces at that time. Her husband died two months and sixteen days before she did.[21]

Ellis and Boone:

LeRoy and Mabel Wilhelm wrote that “Peter Isaacson, farmer, settled at the Meadows and became the bishop of the ward. Martha, his wife, was Relief Society worker and honest beyond words. They were the parents of Isaac and Maria. Isaac Isaacson married Zina [sic] Peterson [this sketch] and reared a large, excellent family in St. Johns, of teachers and educators.”[22]

The Wilhelms then wrote the following about Isaac Isaacson’s sister: “Anna Maria, just 17, later became the wife of Edwin M. Whiting, whom she met in Brigham City.”[23] Anna Maria and Edwin Marion Whiting were the parents of the five Whiting brothers, Edwin Isaacson usually known as E. I., Earnest, Ralph, Lynn, and Arthur, who put together a business conglomeration which included over one hundred service stations, a motel chain, general stores, farms, cattle ranches, truck lines, sawmills, and general contracting firms. The Whiting brothers consortium became the biggest employer in the St. Johns area during most of the twentieth century. One of their employees thought that the secret of their success was E. I.’s “uncanny talent for collecting overdue accounts in labor;” he “coined a subtitle for The Cash Store: We give credit to anyone.”[24]

Pioneer Dolls: Eagar and Snowflake. In her manuscript, Snowflake Girl, Louise Larson Comish wrote, "A little girl's earliest plaything is a doll. I had many dolls." Some of her dolls were from toy shops but many were homemade - one from a yellow crook-necked squash dressed in flour-sack muslin, some from "sucker" ears of corn with new-silk hair, and others from white himsonweed blossoms stacked together. In the photograph above, girls at Eagar have lined up on the schoolhouse porch with their cloth dolls; from left: Freda Wiltbank, Nellie Hale, Idella Wiltbank, Mildred Norton, Isabell Norton, and Verena Wiltbank. In the lower photo, girls in Snowflake show off china-headed dolls and buggies; from left: Charlotte Ballard, Marie Smith, Josephine Smith, unidentified, Thora Rogers, Cora Rogers, and Myrtle Smith. One Christmas Ethel Coleman's mother told her that Santa was too poor to bring a new doll but he would put a new dress on it - which Santa did, much to her delight. Photos courtesy of Iris Finch (above); LeOla Rogers Leavitt (below).

Pioneer Dolls: Eagar and Snowflake. In her manuscript, Snowflake Girl, Louise Larson Comish wrote, "A little girl's earliest plaything is a doll. I had many dolls." Some of her dolls were from toy shops but many were homemade - one from a yellow crook-necked squash dressed in flour-sack muslin, some from "sucker" ears of corn with new-silk hair, and others from white himsonweed blossoms stacked together. In the photograph above, girls at Eagar have lined up on the schoolhouse porch with their cloth dolls; from left: Freda Wiltbank, Nellie Hale, Idella Wiltbank, Mildred Norton, Isabell Norton, and Verena Wiltbank. In the lower photo, girls in Snowflake show off china-headed dolls and buggies; from left: Charlotte Ballard, Marie Smith, Josephine Smith, unidentified, Thora Rogers, Cora Rogers, and Myrtle Smith. One Christmas Ethel Coleman's mother told her that Santa was too poor to bring a new doll but he would put a new dress on it - which Santa did, much to her delight. Photos courtesy of Iris Finch (above); LeOla Rogers Leavitt (below).

Notes

[1] Rogers wrote this sketch “as told to her by her mother, Elsina Peterson Isaacson, and combined with excerpts from other members of the family as they remember them.” Pioneer Women of Navajo County (partial manuscript PWA), Mesa FHL.

[2] Maria Tyggeson came to Utah with the Robert F. Nelson Company of independent wagons in 1859, but Thomas Peterson is not known to have been part of this company. Most of these people came to the U.S. aboard the William Tapscott and then traveled to Florence, Nebraska, by rail. MPOT.

[3] This statement is apparently not correct. Richard Bennett wrote, “During the thirty-four-year lifespan of the Endowment House . . . no children, either living or dead, were sealed to their parents.” Bennett, “Line upon Line, Precept upon Precept,” 51.

[4] John Anderson and wife may be John Anderson (age 40) and Fredericka (age 26). 1870 census, Fountain Green, Sanpete Co., Utah. Melitón González Trejo (1844−1917) was born in Spain. The wife mentioned here may be Marianne Christensen (1840–1905); they had one daughter born in 1876 who would have probably been traveling with them.

[5] The crackers were probably hardtack or the unleavened bread used by armies. Zwieback is a biscuit that is sliced and toasted after baking.

[6] Iron Springs is generally identified as a stage stop between Phoenix and Wickenburg, and by 1890 Phoenicians were building summer homes there. However, the location mentioned in this sketch is before crossing the Hualapai Desert and before Hackberry. No area called Iron Springs was found on old maps, but there is a Gold Springs in this area on an 1892 map. Therefore, Clayton probably added “which is now a beautiful resort” thinking this was a reference to the Iron Springs near Phoenix. Granger, Arizona Place Names, 347.

[7] Nineteenth-century folklore assumed that cattle horns influenced everything from the amount of milk produced to the amount of flesh on an animal. In reality, an animal that is sick may have horns that feel hot to the touch, but generally nineteenth-century remedies (dehorning or drilling a hole and inserting “medicine”) were either ineffective or detrimental.

[8] Today, this is usually spelled “Hualapai.”

[9] This is likely Albert King Thurber (1826–88), president of the Sevier Stake. Some of Thurber’s children moved to Mexico and then after 1912 to Arizona. “Albert King Thurber and Thirza Malvina Berry,” in Larson and Haws, Harry L. Payne and Family, 249–54; “Albert King Thurber,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:519–21.

[10] Edward E. Jones (1852–1935) was born in Wales and died in Provo, Utah. For information about the Jones and Kimball trip, see Caroline Marion Williams Kimball, 362. For additional information about David Patten Kimball, see W. Earl Merrill, “David Patten Kimball,” in Clayton, PMA, 265−67; David Patten Kimball, FWP sketch by Harry L. Payne, ASLAPR.

[11] Possibly this should read “go on to the Salt River Valley.” Both of these men first settled at the Lehi/

[12] So many Mexicans came to Arizona in the 1860s and 1870s that pesos were as important as dollars. In 1878 the railroad brought in Chinese laborers—more than 1,100 the first month. With the completion of the railroad in 1883 (and even with the influx of Mormon pioneers), trade shifted from north-south to east-west. Sheridan noted that “Arizona became more and more tied to the rest of the United States and less to northern Mexico.” Sheridan, Arizona, 117, 122−23; see Juanita Gonzales Fellows, 174.

[13] The exact route is difficult to determine from this description. It could be that this should be Thatcher, not Tucson. The Salt and Gila Rivers do not meet until downstream from Mesa. The group could have traveled up the Gila River to Thatcher and then around the Graham Mountains to the San Pedro River (and St. David), or they could have traveled up the Gila and Santa Cruz Rivers to Tucson and then east to the San Pedro River and St. David.

[14] Mr. Hornsogle is unidentified at this time. Usually this name would be written Hornswoggle, but a person by this name was not found in the 1880 census for Arizona, the Arizona vital records, or the findagrave website for Arizona. He may have been using a German name which was entirely different from Hornswoggle.

[15] Safford’s mining interests are best seen in the history of Tombstone. Faulk, Arizona, 145–49.

[16] Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915) served seven terms as president of Mexico from 1876 to 1911. His cordial relationship with Mormon colonists is discussed by Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, 56, 59.

[17] Carl Hayden (1877–1972) was Arizona’s representative in Congress, first in the House from 1912 to 1927 and then in the Senate from 1927 to 1969. He was President Pro Tempore from 1957 to 1969. “Carl Hayden,” in Clayton, PMA, 228–31; Sheridan, Arizona, 205–6.

[18] This man was probably Charles Grandison Curtis (1852–1946), who came to Arizona in 1877 from Utah. He first freighted out of Little Colorado River settlements and in 1880 moved his family to St. David. He is buried in Thatcher. 1880 census, Charles G. Curtis, Mormon Settlement on the San Pedro River, Pima Co., Arizona; findagrave.com #54840283.

[19] Seven miles northwest of St. Johns, the ephemeral nature of The Meadows is illustrated by the LDS congregation, which was first organized as a ward, on March 31, 1883, with Peter Isaacson as bishop, and then discontinued, November 19, 1885, and made a dependent branch of the St. Johns Ward. Wilhelm and Wilhelm, History of the St. Johns Arizona Stake, 72−73.

[20] Polish Lambson is Apolos B. Lambson (1843–1914); he was married to Angenet Bates, was at Brigham City with his family in the 1880 census, and died at Ramah, New Mexico. Erastus and Joseph Buck Wakefield settled at The Meadows and then moved to Snowflake. Erastus and Mariah Wakefield also lived in the Gila Valley for many years; see photo, 105. Ibid., 268; Aretha Morilla Bates Wakefield, 755.

[21] AzDCs were not found for either Elsina or Isaac Isaacson. Isaac died September 4, 1944, at St. Johns.

[22] Wilhelm and Wilhelm, History of the St. Johns Arizona Stake, 267.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., 298