H

Roberta Flake Clayton, Louesa Harper Rogers, Matilda Haws Lewis, Burton R. Smith, and Anna Elese Schmutz Hunt, "H," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 231-304.

Mabel Ann Morse Hakes

Author Unknown[1]

Maiden Name: Mabel Ann Morse[2]

Birth: April 10, 1840; Macomb, McDonough Co., Illinois

Parents: Justus Morse and Elizabeth Towne

Marriage: Collins Rowe Hakes;[3] March 29, 1857

Children: Ann Eliza (1858),[4] Avis Caroline (1860), Sarah Melissa (1862), Hellen Lotheta (1864), Lottie Mabel/

Death: January 19, 1908; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Ann, as she was called, was the daughter of Justus and Elizabeth Morse, who had joined the Church before her birth. Although the Prophet Joseph Smith was killed when Ann was only four years old, she remembered him well. He loved little children, and she remembered his kindness and that he held her on his knee. Her father had hidden the Prophet for several nights in his cornfield, and stood guard when his enemies were seeking his life.

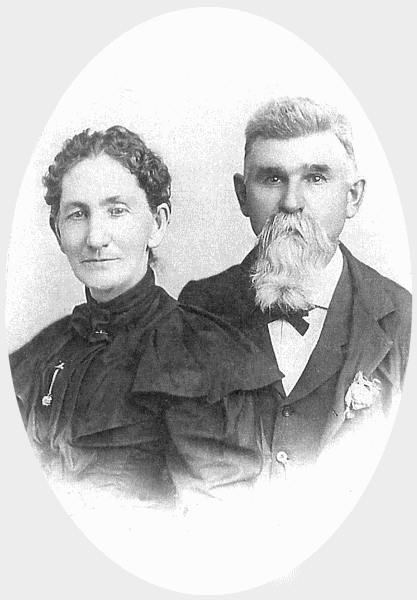

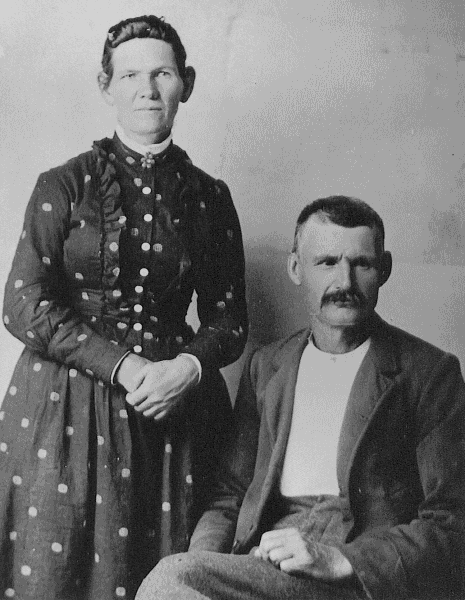

Mable Ann Morse and Collins Row Hakes, photograph by Hartwell, Phoenix. Photo courtesy of Philip Stradling.

Mable Ann Morse and Collins Row Hakes, photograph by Hartwell, Phoenix. Photo courtesy of Philip Stradling.

Ann’s mother died in 1845, and her childhood was greatly saddened on this account. The family was driven from Illinois with the other Saints and crossed the plains in 1850 in a company led by Amasa Lyman and Brother Charles Rich. During times of discouragement on that long hard journey, this little girl would lean against the wagon wheel and pray for the Lord to help them.[5]

They spent the winter in Great Salt Lake Valley and then continued on to San Bernardino, California, where she was baptized January 1, 1852, by William J. Cox.

Her early life was not easy, but perhaps because of this, she learned early and well the lessons of self-control, mastery of tongue, and a deep understanding of the sorrows of others. Her own children never heard her voice raised in anger; she never argued or quarreled with anyone. Sometimes in moments of stress she would leave the house for a few minutes then come back in pleasant and smiling. She befriended many a motherless girl and boy in her lifetime and helped the weak to be stronger.

As the Hakes family responded many times to the call to settle new frontiers, they more than once had the opportunity to share their food with the Indians who appeared at their door. Once, when all they had to eat was corn meal mush, some Indians came who were so hungry that they scooped the mush up with their hands and licked it off boiling hot.

All their encounters with the Indians were not pleasant, however. One day when Collins and all the other young men in town were away serving as soldiers in the Black Hawk War, an Indian walked into the Hakes home saying that he disliked young Hakes, so was going to take his wife; [the Indian] grabbed Ann. Her mother-in-law, Eliza, quickly seized the butcher knife and started towards him. Seeing that she meant business, he let Ann go and ran away.

In 1868, she was chosen to be a counselor in the Kanosh Ward Relief Society in Millard County, Utah. This began a forty-year period of service, during which time she held one office or another in ward or stake Relief Societies wherever she lived. After they moved to Mesa, Arizona, she was president of the Mesa Ward [Relief] Society from 1885 to 1890, when she was chosen to be a counselor on the stake board. In 1892, she was called to preside over the Maricopa Stake Relief Society, which she did faithfully and well. Among other things, she and her counselors traveled with horse and buggy to raise funds to build a Relief Society Hall.

From the beginning, her home was always open to Church visitors from Salt Lake City. At one time, Brigham Young approached Kanosh with a conference party. He sent a man ahead saying, “Go to Brother Hakes’ house and tell Sister Hakes to have dinner ready for twenty-five people in one hour.” She had a good meal waiting for them when they arrived. During the course of her lifetime, many of the General Authorities stayed at her home and ate at her table.

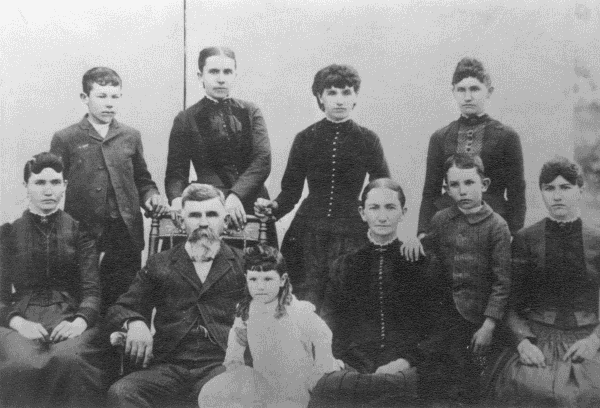

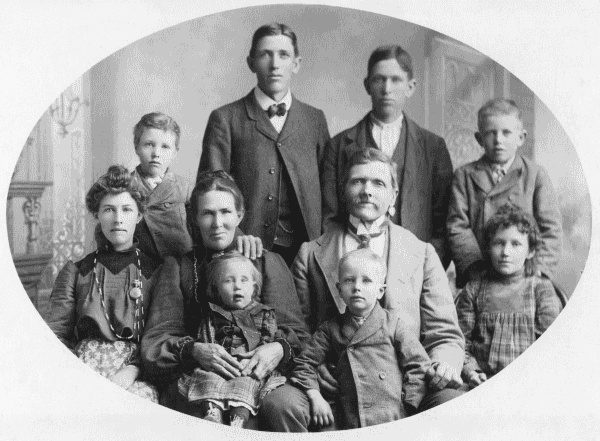

Mabel Ann Morse Hakes (seated) with husband, Collins, and children. Front row (left to right): Harriet Jane, Collins Rowe (father), Ruby Amanda, Mabel Ann (mother), Daniel Edgar, Effie Elizabeth; Second row: Collins Riley, Ann Eliza (406), Lottie Mabel, Sarah Melissa. Photo courtesy of Phillip Stradling.

Mabel Ann Morse Hakes (seated) with husband, Collins, and children. Front row (left to right): Harriet Jane, Collins Rowe (father), Ruby Amanda, Mabel Ann (mother), Daniel Edgar, Effie Elizabeth; Second row: Collins Riley, Ann Eliza (406), Lottie Mabel, Sarah Melissa. Photo courtesy of Phillip Stradling.

Heber J. Grant, who later became President of the Church, knew her well.[6] He said that she was an excellent cook and admired her for goodness of character as well as the spontaneous and ready wit with which she was blessed. She had a way of saying humorous things in such a way as to take care of herself in any situation, yet without giving offense. Her wit was most amusing to others, but she never smiled at her own jokes, making her funny remarks in seeming innocence. President Grant said that he had watched her as long as he had known her to see if anyone ever got the better of her verbally—that he didn’t believe anyone ever would, and that her husband certainly never had.

She was the Mesa Representative to the Woman’s Suffrage Convention in Chicago in 1893. Here one irate gentleman speaker said that women had no business in public affairs but should be home sewing buttons on shirts and darning their husbands’ socks. To everyone’s delight and his discomfiture, Ann arose with dignity and informed him that he would be pleased to know that all the buttons were on and the socks darned before she left home.

Two years before her death, she suffered a stroke and was never well again. Her children took turns caring for her in their homes. In spite of her suffering, she never murmured or complained, and always did for herself all that she was able to do. She died January 19, 1908, and was buried in Mesa, Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

Not mentioned in this sketch is the family’s move to Bluewater, New Mexico, in 1905. Ann Hakes was released as president of the Maricopa Stake Relief Society in 1904 because of this move.[7] Her husband was made the first bishop of the Bluewater Ward in 1906 and served until 1915.[8] However, Ann may not have spent much time in New Mexico because she died in 1908, after her children had taken care of her for two years following her stroke.

In 1893, Collins and Ann Hakes attended a national Hakes reunion at Niagara Falls and then the Chicago World’s Fair. A sketch for Collins states that “it was a joyous occasion for he and his wife, who had spent many years of their lives on the western frontier.”[9] As part of the World’s Fair, the World’s Congress Auxiliary organized the World’s Congress of Representative Women, a week-long congress devoted to women’s suffrage and other women’s issues. Almost 500 women from twenty-seven countries spoke, and 150,000 people came to the congress; it had the largest attendance of any congress held at the World’s Fair. Although Ann Hakes’s retort to her heckler is a charming bit of Arizona history, probably the most important part of this congress for LDS women was the healing of a rift between LDS women and women who had been outspoken against polygamy. The Utah delegation, not all of whom were LDS, sponsored a program on May 19, 1893, and at the closing, Emmeline B. Wells asked that Rosetta Luce Gilchrist come to the stand. Gilchrist then sat between Wells and Zina D. Young as a symbol of universal sisterhood. Most participants probably knew that Gilchrist had published a fictional account, “Apples of Sodom: A Story of Mormon Life,” which was derogatory to the Mormon lifestyle. This demonstration of forgiveness by Wells and Young was a first step toward cooperation between LDS women and the national suffrage leaders.[10]

Louisa Bonelli Hamblin

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Louisa Bonelli

Birth: October 29, 1843; Winegarten, Thurgau, Switzerland

Parents: Hans George Bonelli and Anna Maria Aman (Ammann)

Marriage: Jacob Vernon Hamblin; November 16, 1865

Children: Walter Eugene (1868), Inez Louisa (1871), George Oscar (1873), Alice Edna (1876), Willard Otto (1881), Amarilla (1884)

Death: December 10, 1931;[11] Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Louisa Bonelli, the daughter of Hans George Bonelli and Maria Aman, was born October 29, 1843, in the little mountain town of Winegarten, near Berne, Switzerland, a region near Italy where Italian is frequently spoken. The family name, Bonelli, is Italian. The story is that during the sixteenth century, two brothers Bonelli were on the losing side of a political uprising in Italy and were forced to leave the country to save their lives. George Bonelli’s progenitor made it safely into Switzerland, where he married and was absorbed with the German-Swiss of that area.[12]

Louisa learned to work when she was very young. At the age of six years, she had the task of knitting all of the stockings for the family of eight. She never had time to play but would watch the other children while she sat knitting. It was the custom to bake and do the laundry in the spring and in the fall. Everyone helped and it took two months to do the job.

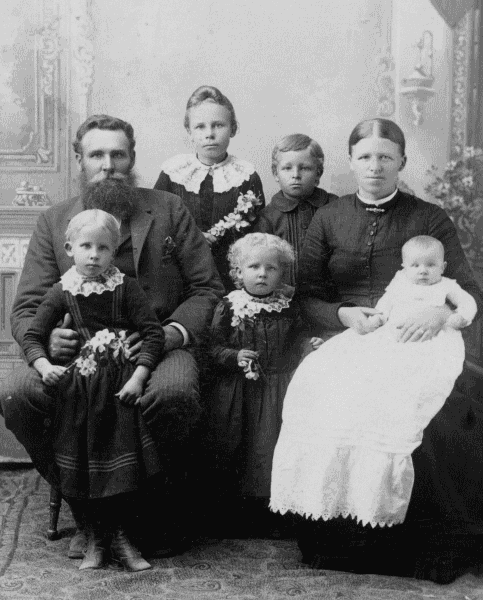

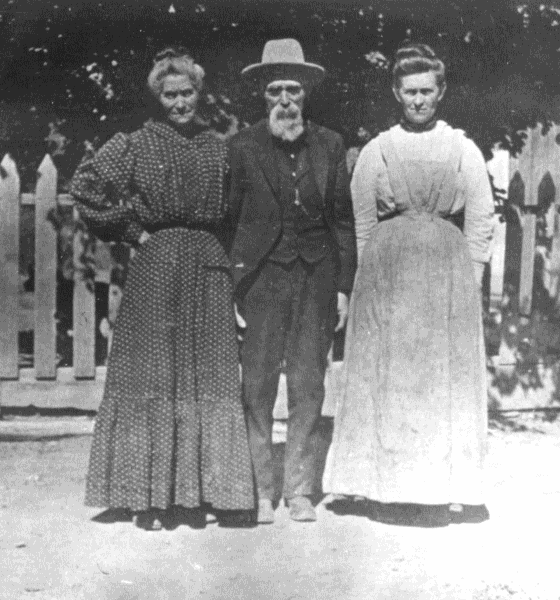

Louisa Hamblin with children, Alice Edna and Willard behind chair, Inez ouise (probably left) and Amarilla on floor; Williams Gallery, Safford. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

Louisa Hamblin with children, Alice Edna and Willard behind chair, Inez ouise (probably left) and Amarilla on floor; Williams Gallery, Safford. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

Missionaries from America came to the family, and they were all baptized when Louisa was ten years of age, in the winter of 1852. It was so cold that the ice had to be broken, and their clothes were frozen stiff before they could get to the house and change them. Some of their neighbors, suspecting what was happening, sat in the edge of the forest to watch the baptism.

Louisa had to walk one and a half miles to go to school. After joining the Church, she was treated so badly by her associates that her parents sent her to the city to live with friends, members of the same faith, to attend school.

For five years following their conversion, the Bonelli family saved every possible “pence” to apply on a fund to pay their way to Utah, in America, the land of Zion. In 1857 they sold their home and auctioned off their household goods. Father and Mother, sons George and Daniel, and daughters Mary and Louisa went by stage coach to Paris and on to Le Havre on the French coast and across the English Channel to Liverpool, England, the gathering point for European Saints. Imagine leaving the beautiful green mountains and blue lakes of Switzerland for the barren deserts of the West, not even knowing what it would be like; but they had the spirit of gathering.

The emigrants boarded the ship George Washington and set sail for Boston, crossing the ocean in six weeks.[13] Louisa said, “I never was seasick and didn’t know enough to be afraid. I used to stand on the deck and watch the great waves roll up. Sometimes they would wash over me, but I held on to the post and enjoyed it.” From Boston they went by train to Albany, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Chicago, the latter being only a little town at that time. They waited in Iowa City three weeks while the handcart company was forming and the handcarts were being constructed. Then the carts were loaded with necessities only. Companies were organized in hundreds and fifties and tens. The overall captain of the company was Israel Evans, and the subcaptain was named Huntington. This company left the latter part of May 1857 and consisted of 149 people, 28 handcarts, and 4 mule wagons to haul extra provisions.[14]

Quoting Louisa:

The weather was warm and lovely. I walked all the 1300 miles to the Salt Lake Valley, helping to pull a cart most of the way. In the company was a crippled girl about eight years of age. She had to be carried all the way. I had my turn at carrying her on my back. As time for making camp neared, the children were permitted to leave the train and gather fuel (buffalo chips) for the campfire. This was like letting school out, and we enjoyed running about and being released from [pulling] that handcart.

Flour and bacon were the main items in the diet. Meat from an occasional buffalo added variety. Some of our group did not know how to bake bread over a campfire and at first they just mixed their flour with water and ate it raw, until they learned from the others.

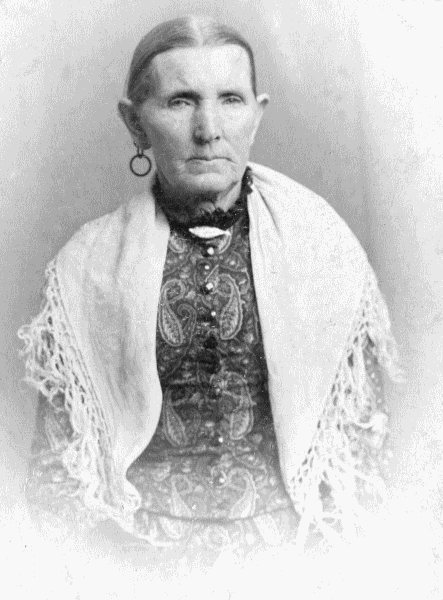

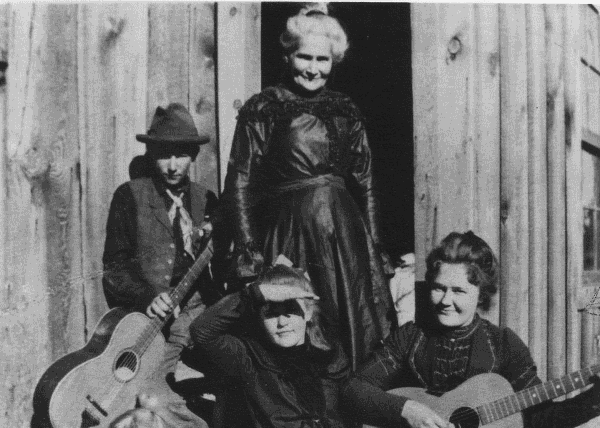

Louisa Bonelli Hamblin. Photo courtesy of Scott Lee.

Louisa Bonelli Hamblin. Photo courtesy of Scott Lee.

Later, rains came and mud replaced the dust of the trail. Louisa often had to stop and dig her wooden shoe out of the mud and put it back on her foot.

There was an old woman in the company. Everyone was expected to either push or pull, but this old lady held to the cart and was a drag because she was weak. Some of the people reported her to the captain, and she was warned. When Mary and Louisa heard of this, they took pity on her and told her, “You can hold onto our cart and we will not tell on you.”

The Missouri River was crossed by ferryboat, but the other rivers had to be forded and gave plenty of trouble and delay. This handcart company reached the valley on September 12, 1857, just in time to help with harvesting, and thereby [the company members] earned enough wheat and vegetables to see them through the winter.

George Bonelli was a weaver. The family was directed to go south to Santa Clara in the Dixie country where their trade as weavers would be useful in the cotton that was expected to be grown there.[15] Wool was, of course, usually used for clothing. It was Louisa’s job to pick the wool free of sticks and burrs and then to wash it. She had little time for anything else and had little schooling in America.[16]

On November 16, 1865, Louisa married Jacob Hamblin in Salt Lake City. She was his fourth and last wife.[17] Jacob was called to serve on the frontiers making friends with the Lamanites and in charge of Indian affairs.[18] In the spring of 1870, he moved his family to Kanab, where they lived for several years.

Jacob, having been relieved of his missionary duties, moved his family to Arizona (Eagar) in the spring of 1881 and in a short time moved them on to Pleasanton, in New Mexico (now Glenwood), a new and isolated area in Indian country. The renegade Chief Geronimo passed this way on his many raids, and they had many an Indian scare. With Jacob being away so much of the time, Louisa had double responsibility. If the signal was given, she would have to move her children into the big community store and fort, often awakening them in the middle of the night. She said that one family discovered, after making a quick transfer, that they had forgotten to bring their baby and he was asleep in his crib. Two young boys were dispatched to go back and bring the baby. During the three years they lived in Pleasanton, upwards of twenty people were killed by the Indians within a radius of ten miles.[19]

Quoting Jacob [Hamblin Jr.] (son of Priscilla):

I lived with Aunt Louisa for one year at Pleasanton. I was only a young man. We were trying to open up a new farm there. Bacon and Johnnie cake were about all we had to live on. The way Aunt Louisa cared for her home and table deserves praise. Everything shone with cleanliness. She would mend and patch my hose and my shirts and iron them so fine that I would be proud to wear the patches. She taught me real economy. She covered a box with newspaper, for my things. Should I think my socks were too old to mend and throw them away, she would send the girls to get them and I would find them all clean and mended in my box.

One of the nicest things I ever heard Aunt Louisa tell was at an Old Folks Party at Nutrioso. In giving a little history of her experiences when crossing the plains, she said there were men in the party who talked of the farms and homes they hoped to have, where they could live in peace and grow the wheat and potatoes and food needed for their family. Others talked of the gold they were going to have and how they would be rich. Those who wanted to get gold drifted away from the Church and, so far as she knew, died in poverty. Those who talked of home and farms did build fine homes and lived in peace and plenty.[20]

The water at Pleasanton must have been contaminated, for in the summer of 1886, the whole community was stricken with a fever. There were not enough able-bodied to care for the sick. Jacob Hamblin was among those stricken. Louisa nursed him, since Priscilla, another wife, was among the sick ones. Early in the morning of August 31, 1886, the word spread over the little town, “Jacob is dead.” The story of his death and burial has been published by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, March 1950.[21]

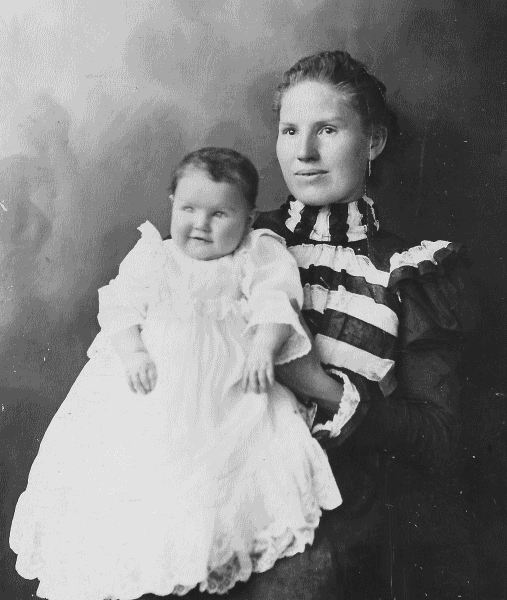

Louisa Bonelli Hamblin and unidentified child; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Louisa Bonelli Hamblin and unidentified child; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

It soon developed that the settlers did not have clear title to their lands and the community was abandoned. Louisa spent the winter of 1886−87 with the Maxwell family in Pleasanton. In the spring, Fred Hamblin, Jacob’s brother, came and took her to Alpine, Arizona, and helped her get established in a log cabin. Her oldest son, Walter, was eighteen years of age. He helped support his mother by driving freight teams and working on the railroad near Flagstaff and across northern Arizona. Louisa managed to get the necessities of life for her six children. Her youngest was two when Louisa was left a widow. She was a hard worker and a good manager.[22]

Louisa was a small woman with black hair, which had only a very little gray when she died. She was slender and quick in her movements. She had blue eyes. She had three sons, Walter, George Oscar, and Willard Otto; three daughters, Inez Louisa, Alice Edna, and Amarilla.[23] When her children had all married, she went to live with her daughter Inez (Lee) in Thatcher, Arizona, for the final twenty years of her life. She died December 10, 1931, and was buried in Thatcher. It was impossible to take her to Alpine for interment beside her husband because heavy snows made all highways impassable.

Ellis and Boone:

Two well-known figures from completely different generations have provided brief references to the life of Louisa Hamblin. Stewart Udall, her great-grandson, and a prominent figure in U.S. politics and the environmental movement, mentions Louisa in his book about rethinking the history of the Old West. Although he states that much of his information was based on Pearson Corbett’s biography of Jacob Hamblin, Udall is imprecise with dates, gets the wives confused, and provides no references. He does, however, mention the short time during 1885 that Louisa and Jacob Hamblin spent in Mexico to avoid prosecution for polygamy which adds to this sketch. A century earlier, while Louisa was still living in Utah, the Colorado River explorer, Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, ate meals at her home for three weeks and “found her a very nice, sensible woman.” He described her as “rather attractive in her personal appearance.”[24] Each of these two men reminds us of Louisa Hamblin’s place in western and Arizona history.

Margaret McCleve Hancock

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Margaret McCleve

Birth: September 17, 1838; Crawford, Down, Ireland

Parents: John McCleve and Nancy Jane McFerren

Marriage: Mosiah Lyman Hancock (1843);[25] January 9, 1857

Children: Moroni (1857), Margaret Clarissa (1858), Mosiah Lyman (1860), Levi McCleve (1862), Elizabeth Jane (1864), John Taylor (1866), Joseph Smith (1867), Sarah Catherine (1869), Mary (1872), Amy Elizabeth (1873), Thomas (1875), Rebecca Reed (1877), Annie Minerva (1880)

Death: May 4, 1908; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Few pioneers of Arizona ever had the experience of having free access to the beautiful grounds of the lord’s estate, and yet the early childhood of the subject of this sketch was thus spent.

Margaret was the third of ten children, born in Belfast, Ireland, on September 17, 1838, to her parents, John and Nancy Jane McFerren McCleve. Her father was one of the caretakers on this large estate situated near the ocean. The children were allowed to roam where they wished, and in them was born a love for the beautiful that always remained with them. Living so near the ocean, she and her brothers and sisters liked to follow the waves and dash through them when they were not too high. In [the following] years, when trials came so thick and fast it looked as though the trouble might engulf her as did the waves on the Irish shore, the pleasant memories of her happy childhood sustained her.

Margaret McCleve Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

Margaret McCleve Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

About the year 1845, two Mormon elders came to their home, and her father and mother accepted of their teachings. After the missionaries left, the family did not see any more members of the Church for four years. Margaret and her sisters Sarah, Catherine, and Isabell were baptized after dark in the Irish Sea, August 25, 1850, by John D. T. McAllister.

When Margaret was twelve years old, the desire to go to America was so strong that every cent that could be spared from the family income was saved for the trip. It was soon found that it would impossible for all to go at once, so the two eldest daughters were sent with some friends who were emigrating at that time in the hopes that they might get work to help the family.[26] This was indeed a sad parting, one that Margaret never forgot. It was three years before the family was reunited when the remainder of them finally accumulated enough to bring them to the land of their dreams.

The sea voyage of the family lasted five weeks, and there were many storms, so the ocean trip was anything but pleasant. When they landed, they went from Boston to Winter Quarters, [Nebraska] or [Council Bluffs] Iowa by rail. Here they had to stay about two weeks while the men fixed up handcarts to convey their belongings.[27] What seemed [like] only the bare necessities were put on these carts which were drawn and pushed by the parents while the children walked along, the smallest ones clinging to their mother’s skirts. But even as meager as their belongings were when they started on the long trek across the plains, everything possible was left by the side of the trail as the parents wearied.[28] The father fell a victim of fatigue and lack of nourishment as he deprived himself that his children might have his portion, and finally he died and had to be placed in a wayside grave.[29]

Undaunted, the brave wife and mother kept on with the company. Everything was so new and strange. The first Indians they saw almost frightened the children to death. Just as supplies were about all gone, others were sent out from Salt Lake City, Utah, and before they reached their destination, President Brigham Young himself came out to meet them. The meeting of the mother and her daughters was saddened by the loss of their beloved father. The girls had found homes with excellent families and were able to assist their mother in providing for the family.

Margaret McCleve Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

Margaret McCleve Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

On January 9, 1858, when she was twenty years old, Margaret was married to Mosiah L. Hancock. They settled in Payson, Utah, where they lived a few years, then moved to Salt Lake City. Even here they remained but a short time, when they were called to help settle Southern Utah, and from there to Arizona in 1879. When the family was ready to start, her husband was called away on Indian service. Their eldest son was nineteen years old by now, so Margaret decided to undertake the journey as planned. She seemed to possess the courage of her mother in this undertaking, so in company with her husband’s brother and family, she and her children came along. They reached Taylor, Arizona, on New Year’s Day, 1880.

Pioneering experiences in three places in Utah had taught Margaret what pioneering meant, but even those hardships were mild compared with some that she passed through in helping settle this new country so far away from civilization. Her husband joined the family later, and they made their home permanently in Taylor.

Margaret was a natural-born nurse, and as there were no doctors in this country at this time or for many years after, she gave her services wherever they were needed. Margaret was called and set apart by Stake President Jesse N. Smith for a mission to the sick and afflicted. She was an excellent midwife and has assisted in bringing hundreds of babies into the world. Nor did her interest in them end when they were babies, as she always knew and claimed them as her own.

She was the mother of thirteen children; the eldest died in infancy, the others lived to maturity. The greatest sorrow that ever came to her was when her son Joseph was taken away from her. It was the day before he was to be married. Everything was ready for the glorious event, everything but one little last-minute errand to the store in Snowflake, three miles away. With a smile and a jaunty wave of his hand, he rode away on a highstrung young mare they had raised. He was riding along when suddenly she reared up and fell over with him; in some way the horn of the saddle hit him, crushing his skull. Help soon came to his assistance, and he was rushed to Snowflake to the doctor, but as nothing could be done for him, he was taken to his home in Taylor. He never spoke after the accident, but when his mother came to his bedside, he looked into her eyes and squeezed her hand. His burial occurred on the day and hour that he was to have been married.[30] It seemed this loss was more than Margaret could bear, but her faith sustained her, and she tried to ease her own pain in making others’ [pain] lighter.

In 1907 she had two serious illnesses and many times her life was despaired of, but through the tender kindness and loving care of children and friends, she recovered and lived, a comfort and blessing to all who knew her until May 4, 1908. During her last illness, she heard of her husband’s death; he was at that time with a son on the Gila River.[31] He did not precede her long into that land where she looked forward to a happy reunion with all those “she had loved and lost a while.”[32]

Ellis and Boone:

As a midwife, Margaret Hancock’s picture hangs on the wall of the Doctor’s Room at the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum in Salt Lake City. James Jennings, however, told a more personal story about Margaret Hancock as a midwife:

Margaret Hancock's cabin in Taylor, 2014; Diane Kriter, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Margaret Hancock's cabin in Taylor, 2014; Diane Kriter, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

One of my most cherished memories is of the little notion store operated by Grandma Hancock in the living room of her home. Upon entering I stood with mother before a counter, behind which Grandma stood. She kept babies under this counter, or so I was told, and whenever any family wanted a new baby, it was no problem. Just go to Grandma Hancock’s store and she would reach under the counter and hand one over, no charge. I was five years old when mother went down and brought home our baby brother, who was later to become Judge Renz L. Jennings. I marveled at the simplicity of the process.[33]

Margaret’s marriage to Mosiah L. Hancock was a second marriage for Mosiah, and he eventually had three other families. It is therefore not surprising that Margaret is the family member who is important to the history of Taylor (with other wives and children settling elsewhere). The Taylor community has preserved her cabin as an example of the pioneer heritage in this area.[34]

Marium Dalton Hancock

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview[35]

Maiden Name: Marium Dalton

Birth: February 1, 1864; Virgin City, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: John Dalton Jr. and Ann Casbourne[36]

Marriage: Mosiah Lyman Hancock (1860);[37] November 2, 1881

Children: John Lyman (1883), Charles Levi (1885), David Ammon (1887), Heber Joseph (1889), Alta May (1891), Margaret Ann (1893), Hyrum Smith (1896), Oliver Perry (1898), Richard Hobson (1900), Daniel Wells (1902), Amanda Zelpha (1904), Warren Edward (1906), Ella Lavora (1908)

Death: October 29, 1944; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Born of pioneer parents, Marium Dalton herself became a pioneer. She was born February 1, 1864, at Virgin City, Washington County, Utah, the daughter of John and Ann Casbourne Williams Dalton. When only a child of eight years, Marium says she had to go out to work and earn her living, working for a neighbor with whom she stayed for two years.

When she was ten, her mother had a paralytic stroke and the whole care of her devolved on Marium and her sister Jemima, who afterwards became Mrs. Simon Murphy. They carried their tiny little mother, who at her best never weighed more than eighty pounds, around in their arms like she was a baby. A miracle of healing was effected through the faith of the two daughters, who carried their mother to see Brigham Young on one of his rare visits to Southern Utah; he blessed her and promised her life and health. “She was instantly healed and walked home unassisted,” remarked Marium.

As soon as her help could be dispensed with at home, Marium again sought employment that the little she could earn, besides her own board and keep, might be used to assist the family. “When I was fifteen years old, I came home one day and found mother with no shoes to wear. I took the only ones I had off my feet and put them on hers, and I, myself, went barefooted, though I was almost a grown lady. Under other conditions this exposure would have been rather humiliating, but, for my dear little Mother, no sacrifice was too great for me to make.”

Marium arrived at Taylor, Arizona, December 28, 1879, and went to work for the family of Joseph McCleve. Her mother was now a widow, and Marium continued to work out for various people to help support her and her brother and sister.[38]

For almost a year she “kept company” with Lyman Hancock. They were married in the autumn of 1880. Their bridal trip was made in a covered wagon to St. George, Utah; there they remained during the winter and until May of the next year. Upon their return, Marium and her husband went to live at Snow Flake Camp, as Pinedale was then called, taking up a homestead. They were among the first permanent settlers. About three or four weeks later, they were joined by Mr. Angle and his son George.[39] The following is Mrs. Hancock’s version of some Indian trouble they experienced, and is quoted as mention is made of other pioneer families living in the vicinity.

“On June 2, 1881 word came for us to go to Taylor at once as the Indians were on the warpath. Lyman then went out to hunt the horses and came across the Indians just north of Snow Flake Camp. He left off hunting the horses and hurried back to let the other settlers know that the Indians were almost upon us. I had everything packed in the wagon ready to go to Taylor, but had to leave it all and start out on foot with my husband.”

Mariam Dalton Hancock family; seated, left to right: Alta May, Marium (mother), Daniel Wells, Richard Hobson, Mosiah Lyman (father), Margaret Ann; standing: Oliver Perry, John Lyman, David Ammon, Hyrum Smith, c. 1904. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Mariam Dalton Hancock family; seated, left to right: Alta May, Marium (mother), Daniel Wells, Richard Hobson, Mosiah Lyman (father), Margaret Ann; standing: Oliver Perry, John Lyman, David Ammon, Hyrum Smith, c. 1904. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

They were soon joined by the Angles and all went to where the Brewer brothers lived, got them together, and went to the Mortensen ranch. By now there was quite a group of men and they considered themselves safe. There they remained overnight.

“The next morning Lyman and some of the men went to where we were living and all we had left was what we stood up in. The Indians had destroyed or taken everything. They killed the chickens, broke the stove, tore up all the books but one, the Book of Mormon, tore up our pictures, and carried the remainder of our belongings away.”

Mr. and Mrs. Hancock went to Taylor, and he worked there until he had accumulated enough means to build another home. Then they returned to Pinedale where their eldest son, John Lyman, was born. During their absence, Jacob and Charles Brewer, Will, Fred, and Beeley Gardner, and Alf Gillespie had settled there.[40] After a short time, the Hancocks moved to Luna Valley, New Mexico, and then to Williams Valley, New Mexico.

“While in Williams Valley,” says Mrs. Hancock, “we were driven into town again by the Indians. This was the worst ordeal I ever went through. We didn’t know what minute the Indians would come and kill us. The men stood guard for two weeks. We didn’t gain anything by going to New Mexico but another son whom we named Charles Levi, so we returned to Pinedale.”

There the family lived for ten years and four more children were born. Thinking to better their condition, another move was made, this time to Bryce. They only stayed there one year, and back to Pinedale they came. Mrs. Hancock is the mother of thirteen children, nine of whom grew to maturity.

When her children were small, Mrs. Hancock washed, carded, and spun yarn and knitted it into socks for her husband and stockings for herself and children. Her husband earned the wool by shearing the sheep. As wool was only three cents a pound much of this time, she utilized it in the making of yarn, mattresses, and warm wool comforts.

In the year 1921, in February, Mrs. Hancock was advised to take her husband to a lower altitude as he was ill of heart trouble. They went to Willcox to the home of their eldest son, and on July 18, 1921, Lyman Hancock passed away.

Mrs. Hancock worked very hard for three years trying to educate her three youngest children. At the end of that time she had to go to Long Beach, California, and have a cataract removed from one of her eyes.

Marium Dalton Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

Marium Dalton Hancock. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 155.

Many occasions presented themselves to prove that the Hancocks were friends of the Indians, in spite of some of the depredations they had suffered, in common with the other early settlers, at the hands of Native Americans. And friendships thus formed were enduring, as instanced by these stories told in Mrs. Hancock’s own words:

When our first baby was about a year old a band of Apaches came to our house. There were about twenty of them. Before we knew it they had come right into the house. My husband’s gun stood in the corner. The Indians wanted to look at it but he would not let them near it. Finally the leader of the band walked up to my husband, lifted his hat up and peered into his face. He then said, “Me sabe (remember) you.”[41] He was the Indian Lyman had found wounded in Water Canyon, about three years before, where he had been shot by the soldiers from Fort Apache, and had taken to Mother Hancock’s home in Taylor where she nursed the Indian until he was well and able to travel. Then she divided what food she had with him and he left. As soon as the Indian recognized Lyman, he began talking very fast to the others and they all went out of the house and the leader took two deer from the saddle and gave them to us.

Another time, after Mrs. Hancock had been away for some time, upon her return to Pinedale, an educated Apache named John Williams came to see her, and in gratitude told her she was all the same as his mother because she had fed him when he was a little boy and told her he would never forget her for her kindness.

Mrs. Hancock is dividing her time among her children, where she is always an appreciated and welcome guest.[42] She passed away October 29, 1944, and was buried in Mesa by the side of her daughter. Her husband, Lyman, had requested that he be buried by the side of his father. His request was granted.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch details many interactions with Native Americans, some of which are different from the usual fears.[43] Even before Church members moved to the Rocky Mountains, missionaries were sent to Native Americans.[44] Brigham Young’s approach in the West, as stated by Latter-day Saint historian Leonard Arrington, “was to be friendly, promote peace, trade fairly, avoid extreme reactions or retaliation, and maintain distance.”[45] Missionaries to Arizona were not only sent to build communities but were also given the task of teaching Native Americans. However, as David Flake wrote, “Soon after the creation of the Snowflake and St. Johns stakes in 1887 all missionary work among the local Lamanites was suspended, mainly because of opposition of the government Indian agents. This suspension lasted almost fifty years.”[46]

Most of the women in these sketches brought their fears of Native Americans with them to Arizona. Mormon towns in Arizona were settled after reservations were established, and by 1886, Geronimo and other renegade Apaches were in Florida and Oklahoma. As Widtsoe Shumway wrote in his book about Alpine, “The Apache were especially feared. A mixture of fact or fable grew up around their fierce and no-holds-barred warriors. The Alma, New Mexico massacre, and the burning of Quemado by Victorio in 1880, and the killing of approximately 1,000 whites in southern Arizona and Mexico during Geronimo’s rampage, and other hit and run tactics made deep impressions on whites throughout early Arizona.”[47] Shumway then discussed Native American and Mormon relations in Bush Valley and concluded, “By 1886, the Indian ceased to be a real threat . . . but people had heard and told so many stories that for a long time they continued to be [intimidated] and were constantly on guard and suspicious.”[48]

Lyman Hancock, and probably to some extent Marium, learned to coexist in peace with the Apaches.

Emma Swenson Hansen

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Emma Swenson

Birth: March 3, 1863; Spanish Fork, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: August Swenson and Bertha Olsson[49]

Marriage: Joseph Christian Hansen; March 24, 1881

Children: James August (1883), Nellie Jane (1885), Edna Bertha (1888), Pearl Catherine (1890), Clara Almina (1893), Joseph Delbert (1896), John Harvey (1899), Minnie Adele (1901), Emma May (1904), Fern Lucile (1907)

Death: March 20, 1945; Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Joseph City, Arizona, is a little hamlet so small that the pulsing, throbbing population of the earth will know nothing of its human-like character and how life, for more than sixty years, has evolved from the pioneer stage to that of a modern-day village which boasts of possessing most all the conveniences which the age has produced. Joseph City is a unique community because it was founded by a group of young people who were sent as colonizers to the bleak Arizona desert by the powerful Mormon leader, Brigham Young.

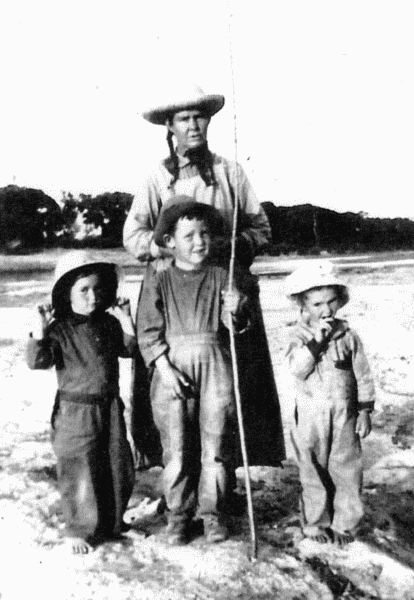

Joseph Christian and Emma Hansen with their children, about 1890 (from left): Nellie, Mary (daughter of Sophia), Edna, James, and Pearl. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Joseph Christian and Emma Hansen with their children, about 1890 (from left): Nellie, Mary (daughter of Sophia), Edna, James, and Pearl. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

The settlers, for the most part, were couples in their first years of wedded life, who answered the call of a mighty leader, remained true to their trust, established homes, and built up a community for their children to possess. These sturdy pioneers lived harmoniously together, and because of unity among their small numbers, their efforts in building up a new country stand as a monument which time can scarcely erase.[50]

Today only a few of these pioneers remain, but should those four or five gray-haired souls suddenly become known to the world, they would be loved and honored because of those moral graces of integrity and thrift which they so outstandingly possess and which humanity everywhere respects and reveres.

Emma Swenson Hansen is truly representative of those who early fought the elements to make the desert a fit and habitable place for white men to enjoy and be glad and proud to call home. She was the second child born to Swedish immigrant parents in Spanish Fork, Utah, March 3, 1863. Her childhood years were mostly spent in Spanish Fork except for a brief time when the Swensons accepted a call to help establish a Mormon colony on the Muddy River in the state of Nevada. The Swensons were always rated high as agriculturalists, and on the Muddy, crops grew surprisingly well. The summer squash that grew on the vine were counted and numbered 145. Other crops grew in like proportions, but due to government regulations concerning taxation, the colony was abandoned after a few seasons, and the Swensons returned to their home in Spanish Fork.

It was in this place that the golden-haired Emma received her education, for which her father paid in produce from his farm. Not all the children of her day were thus favored, for many families were not able to part with any of their produce to pay even for a meager education. The brilliant George H. Brimhall was one of Emma’s instructors, and during the later years of her life, the fine old teacher paid tribute to Emma’s marked ability in penmanship.[51] Emma ranked high with her class in arithmetic and still has in her possession a little book, A Voice of Warning, won as a prize for being the best in spelling.[52]

Not all the education she possessed was learned in the log schoolhouse where slab boards were made into crude seats and where writing was done on slates. Emma was a sturdy Swedish girl, and her parents taught her how to make soil bring forth its bounties. In her childhood she worked long hours hoeing weeds, digging potatoes, milking cows, and doing other tasks about the farm; but tasks like these in the great out-of-doors developed strength of body and taught her many lessons which her quick intellect could grasp and assimilate, to be used when hardships should be grim and difficult to bear.

Spanish Fork had always been her home, and never had she left the family circle for even a few days until she was eighteen years old. It was shortly after her eighteenth birthday, March 24, 1881, that this girl with a youthful round face, honest blue eyes, and golden wavy hair became the wife of Joseph C. Hansen. Joseph had also spent his life in Spanish Fork until he was chosen to help make a settlement on the Little Colorado River in Arizona. He had lived there for three years and had come back to Spanish Fork for a winter’s visit during 1880−1881. In the spring of 1881, he turned his face again southward, taking with him his wife Emma.

The trip back to Arizona was long and tedious, for the horses [had to] travel over weary stretches of desert, up steep mountains and down into the barren lowlands again, cross the Big Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry, [pass] over the desolate wastes [known as the Painted Desert badlands], and then stop in the vastness of these wastes at a mere fort, where a few brave souls were striving to maintain a colony. The Little Colorado River, which stealthily wound its way through the lonely forsaken valley, was lined here and there with a few unlovely, crooked cottonwoods. No other trees relieved the severe and grim aspect of the scene.

“Would you like to go back?” asked the gallant husband as they neared their desert home. The young bride, lonely for her kin and the flourishing town she had left behind, wept, and in her bitterness she answered a most yearning, “Yes.”

But to go back was impossible. Joseph C. Hansen was not a man to go back on his word. He would do his part to make the wilderness a home for succeeding generations; he would do his utmost to answer duty’s call.

Upon reaching the fort [at Allen’s Camp] where the colonists lived to insure protection, the Hansen’s were royally received, and like another member of a large united family, Emma, amid crushing heartache, entered into the duties of life at the fort.[53]

While Emma and her husband still lived at the fort, her first child (a son) was born. With the added burden, she assumed her proper role with other young mothers who took turns going up the river six miles to where the men were striving against all sorts of odds to put in a dam whereby water could be sent through a system of canals to their thirsty farming lands. Here the women cooked in a tent for their valiant heroes, amid flying dust and other discomforts, and did their best to prepare palatable food from the staples—beans and flour.

Because the teams [had to] be fed and cared for during the Sabbath while the men worshipped at the settlement, cuts were drawn each Saturday night to see who must remain on the job over Sunday. It happened that Joseph Hansen drew the fated bean one windy Saturday eve. Sunday came howling in as only an Arizona dust storm can usher in a new day. To add to the disagreeableness of the storm, the horses broke away, thus forcing the husband to leave his wife and two children alone within the mere shelter of the camp tent while he went on foot in quest of the straying animals.[54] His search was long and vexing while the wind grew more fierce. During the prolonged absence, the camp tent was blown down, leaving the bewildered wife to seek the shelter of a wagon box. It was here, pitifully huddled together, that the husband found his family after his trying search for the lost horses. It seems that those dust storms in the uncivilized country presented one of the worst trials that early pioneers had to endure.

The elements were all wild and seemingly beyond the control of a handful of settlers, who had nothing but their physical abilities and splendid powers of endurance to cope against the furies of nature. Fifteen times their dam in the [Little] Colorado River was swept away by treacherous floods, but still the colonists persevered, learning from work and better experiences how to make the arid alkali lands yield them a comfortable living. The last big dam, a cement structure, has withstood the ravages of the worst floods known.[55] At last, when grey hairs announced the passing of many years, Joseph and Emma Hansen, with their staunch associates, beheld a permanent reward for the expenditure of many long and faithful efforts. Their accomplishments can rightly be rated among the noblest in the conquest of the great Southwest.

When the families at the fort separated to build homes, the Hansens made them[selves] a temporary little structure in the fields. From here they moved to a lot in the newly made townsite, where they built a two-roomed house. This served them for a few years until a big brick house of two stories was constructed. After more than forty years, it now stands as silent tribute to its worthy builders, who made of their house a home which was always decently furnished and kept in good repair. In its big front room, the children kept their musical instruments, for Emma and Joseph Hansen were both lovers of music. In her early days, Emma played the organ and the accordion. Her singing voice also helped to add cheer to the somewhat dreary and changeless life of the pioneers.

All of the eleven Hansen children were given musical training, and many of them proved to be musical leaders for the small community. Their tedious practice periods were never annoying to the parents, who were always proud and willing to have their children learn to enjoy and give to others of their musical talents. In other fields of education, the children were encouraged to develop the possibilities of mental endeavor and otherwise add to their usefulness. In times when scholastic training was to be had only through great cost and in distant places, these sons and daughters were spared from the busy life of the farm and earned for themselves places of honor and trust in pioneer institutions of learning. Three of the daughters became successful teachers, one son and two daughters fulfilled honorable missions for their church, and all of the eleven children have been worthy of respect and esteem because of their home training and privileges granted them by exceptional and upright parents.

Because of the spirit that prevailed in the home, because of the unselfish character of its occupants, [and because of] the big lawn, the vines, and shrubs which surrounded the Hansen home, it was always a logical gathering place for many social events. The big front room was not too good or too nice to be used in the early gatherings before the church house was built, and the Hansens opened up their home to give room to some of the Sunday School classes. Joseph and Emma Hansen were unitedly public spirited and their loyal support and generous giving for public enterprises was to them a joyous duty. With uncommon pride, the father justly boasted of his wife’s honesty in the payment of tithes and offerings, for it was she who always carefully and neatly kept the accounts of the family proceedings.

The busy mother filled positions in the ward, acting as treasurer of the Relief Society, serving in the first ward presidency of the Young Women’s organization, and for many years faithfully making her visits as a Relief Society visiting teacher.

Emma Hansen was always unassuming, unpretentious, and modest. She was never domineering, but her family was obedient and knew their work and place. They respected their mother, for she never displayed loss of self-control. Her dignity was not marred with nervous irritations or outward show of unlovely excitement. Though not a fast worker, she was most thorough in the many skills which she possessed and developed. Her head was used to save unnecessary steps, and she acquired unusual ability and powers in good home management. There are few women who could do so many things and do them so superbly well as this pioneer mother. It was a marvel to others of her own sex how she could go into the fields and work with her husband, who truthfully claimed that none could load hay as well as could “Emmy.”

Her gardens were always her pride, and well they might be, for her produce was in demand because of its quality, and her expert hands made a beautiful job of packing and bunching vegetables for market. In this affair the whole family assisted, and many times the late hours of the night had been spent in preparing vegetables for market. From the Hansen orchard, tons of fruit have been picked, crated, or stored. Always the efficient mother worked with her sons and daughters, teaching them by proper example unexcelled lessons in thrift and labor.

She knew how to spin and wove a piece of cloth for several dresses. In the barn, a carpet loom was kept, and all the worn out clothes were eventually turned into bright new carpets. Six of the eight Hansen girls were given new homemade carpets as a gift from Mother to embellish their own homes. Even today, in her seventy-fourth year, she crochets homemade rugs whose oval forms lovingly grace the floors in the homes of her sons and daughters. She is a true giver and considers not the cost of time or effort which is expended in the gift.

Her quilts were quickly made, yet with a precision that characterized them above the commonplace. Today as an old lady her hands shake and tremble, but she is still considered one of the village’s best quilters, and her original quilt designs always find favor.

Emma Swenson Hansen on her fiftieth birthday. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Emma Swenson Hansen on her fiftieth birthday. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

In the little log house, which once served as a home, stands a honey extractor and bee equipment. For years, this dear woman has assisted in caring for bees, extracting and storing honey. Her age makes no difference to her; she still helps to gather the bees’ golden store of sweetness. Until very recent years, she has milked cows, for the Hansens always kept well supplied with dairy stock, and the mother as well as her daughters were first class hands at milking cows. Each morning as soon as breakfast was eaten, whether the weather was warm or cold, blustery or calm, she went with pails of warm milk to feed the little calves and to care for her flock of chickens. She even gathered alfalfa, cutting it with a scythe to give the swine a goodly daily ration. She provided her table with eggs and generally had some to sell. She cured her own pork, hardly ever being without fine bacon, shoulders, or hams. For more than thirty years, her family was never without homemade butter. It was with a feeling of hurt pride that the mother had to submit to creamery butter after an unparalleled record of providing so nicely for her household use as well as selling many pounds of extra good butter to satisfied customers.

Her cellar has always been stocked with home-preserved food. The jellies were particularly fine, as well as the many fruits and vegetables. Many a modern cook might be envious of her ability to make delicious bread, pies, and doughnuts, while her roast chicken and Danish dumplings had a flavor of their own.

She did all the sewing for her family and even made the shirts for her grandsons, who proudly say, “They look just like the store-bought ones.” The family shoes were half-soled by her skillful hands; in fact, she was so frugal and gifted that one wonders if there is anything she could not do.

Because both parents were so diligent in teaching their children the joy of willing work, all contributed to the family income, resulting in a degree of independence. Diversified talents were developed and honest labor brought forth its fruitful harvest.

The pioneers of every time and place have had to endure physical suffering as best they could because of their remoteness from doctors and hospitals. They cared for each other in sickness or death, neighborly kindness and good will taking the place of scientific aid. The Hansen family suffered through the epidemics of measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, flu, and were even in quarantine for smallpox and diphtheria with no break in its members. The mother suffered greatly from toothache, and no dentist being available her teeth decayed in her mouth, leaving aching snags and roots. When the first dentist came to the little town, Emma availed herself of his skill and got herself some new teeth.

The death of her devoted husband on May 4, 1930, at the age of seventy-six, was a very great sorrow to her. For forty-seven years they had loved and toiled together. It seemed she could not go on alone. The marriage of her youngest child shortly after the death of her husband left her more lonely than ever. With her usual self-control, she bore her loss bravely, but soon her golden hair was streaked with gray and suppressed heartache wrote lines on her patient face.

Emma Hansen’s natural resourcefulness would not permit her to waste useful time in needless pining. Two of her winters were spent in Mesa in the Arizona Temple. In the summer of 1933, she took a trip to Chicago to attend the World’s Fair. From the ease with which she got around and her enthusiasm, no one would ever guess that she was past three score and ten.

After the children all married and had homes of their own, part of the old home she rented out, retaining enough for herself. This she made very pleasant and attractive.

Her chickens supplied her with spending money, continued with her garden, tended pigs and bees. Makes quilts, rugs, husks corn, and the rest of the time she reads and does innumerable kindly deeds for her friends and family. Earnings from her investments are loaned out to those in need.

At seventy-four she has a total posterity of sixty souls, ten children, and fifty grandchildren; of that number, only two infant grandchildren have died.

One of the cherished memories in the lives of her children is the homemade toys and goodies at Christmas time; even in the leanest years old Santa always came and brought cheer and happiness.

Emma Swenson Hansen’s life has been a model of excellence, and the sunset of her life is glorified through the vivid reflections of the past; its brilliance mingles with the softer shades of the present, intensifying the beauty of her old age. She has ever exemplified the beautiful ideals of never wasting time, energy, money, or natural resources and has used to good advantage all of her God-given graces. She passed away March 20, 1945.

Ellis and Boone:

Roberta Flake Clayton, who interviewed Emma Hansen, wrote this sketch for the FWP, and submitted it on January 23, 1937. Consequently, the end of the sketch is written in present tense, describing Emma Hansen at age seventy-four. Clayton added only the last sentence when transferring the sketch to PWA.

Because this information was originally written for the FWP, there is no mention that Emma Swenson was Joseph C. Hansen’s second (plural) wife. Daughter-in-law Alice S. Hansen wrote that Joseph “had brought his first wife, Sophia and their small daughter, Mary to spend the winter visiting in his home town of Spanish Fork. The Hansens had come from St. Joseph, Arizona where they had been called to help establish a colony. With the arrival of spring it was time to return to the new Arizona settlement and help put in crops for another year’s harvest. Feeling that he should live the law of ‘plural marriage’ Joseph wisely sought for the most capable girl he could find to take back to the lonely desert home.”[56] So, the wagon trip back to Arizona included Joseph, Sophia, Mary, and Emma.

This also explains the confusion about the number of Emma’s children. Alice Hansen wrote, “While living at the Fort the youthful Emma cared for Joseph’s first wife Sophia who succumbed to an intestinal disorder on August 4, 1883.[57] Emma then assumed the role of stepmother, rearing the motherless four year old Mary. Being a stepmother is sometimes a source of anxiety and frustration but Emma was unfailing in this task. She tried hard to be a real mother to the lonely little girl, accepting Mary as one of her very own. Sophia’s death occurred just one month before the birth of James August, Emma’s firstborn.”[58] In this sketch, Emma is first listed as having eleven children and later as only ten, although the second number may simply reflect Mary’s death in 1904.[59]

Finally, George S. Tanner and J. Morris Richards, later historians in Joseph City, added this about her Emma’s life: “Since the Hansen family was largely composed of girls, some of them worked in the fields along with the men. This was particularly true of the mother, Emma, who cultivated an extensive garden both for home use and for sale to peddlers. Her husband may not have been exaggerating when he called her the best gardener in the county.”[60]

Loretta Ellsworth Hansen

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview

Maiden Name: Loretta “Rettie” Ellsworth

Birth: April 12, 1868; West Weber, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: Edmund Lovell Ellsworth[61] and Mary Ann Bates

Marriage: Hans Hansen Jr.; October 1, 1885

Children: Fannie Gertrude (1887), Winnifred (1889), Mary (1891), Metta Katrina (1893), Georgianna (1895), Donald C. Edwards (1897)

Death: March 29, 1940; Lakeside, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Lakeside, Navajo Co., Arizona

Loretta, “Rettie,” the daughter of Edmund and Mary Ann Bates Ellsworth, was born on April 12, 1868, at West Weber, Utah. The home, at that time, consisted of two rooms, and there were twelve in the family. The boys slept in the barn.

At the early age of nine, Rettie began the duties of motherhood, assisted by two of her sisters. Twin girls were born in the home, and she took over the care of one of them while Nellie and Julia took the other.[62] The hardest part of this child-raising was when the babies had to be fed at night, and the little mothers would have to get up and heat the milk over a “coal oil” lamp. Their labors of love were rewarded, and Effie and Ellie grew up to be beautiful women.

When Rettie was eleven years old, there was a terrible outbreak of diphtheria in the little town, which took the lives of many children, among them a very dear little friend of Rettie’s. She and five other members of the Ellsworth children were stricken at the same time, and when Rettie heard of her little pal’s death, she wanted to go too. She would put her feet out from under the bed covers so she could catch cold, and when the medicine was left by her bed she would empty it out. But fate decreed it otherwise, for instead of Rettie going, two brothers and a sister were taken, all three within four weeks.[63]

In August of 1880, the Ellsworth family left Utah. Six wagons were loaded with the family and their belongings; then there were the cattle and horses to drive. Loretta, who was then twelve, and her eldest sister and two brothers took turns, day about [alternate days?], driving the stock. There were no saddles, so they had to ride bareback. Modesty and custom forbade the girls riding astride in those days, and it was sometimes hard for the girls to sit “sideways” when their horses went over high boulders or had to chase out after the herd.

Their destination when they started was Mexico, but when, after six weeks of travel, they reached Show Low, Arizona, and Mr. Ellsworth saw the beautiful scenery, the tall pines, the clear streams, and good soil, he decided to locate there and [he] bought the Cluff Ranch.

The ranch was near the reservation, and the family lived in constant fear of the Apaches. There were frequent uprisings, fighting even among themselves; one of the worst was enacted during a “Tulapai party” when Chief Petone and two other Indians were killed and two seriously wounded.[64] Rettie’s father and mother were standing outside their home and a shot lodged in the wall behind them. Mr. Ellsworth took the two wounded Indians to his home and nursed them back to life. One of them was Alchesay, who became Chief in Petone’s stead. By this act of kindness, Rettie’s father and family were looked upon with gratitude by the Indians, and they and their belongings were safe from renegade bands. The most dreaded of these were Geronimo’s, the very mention of whose name caused terror in the hearts of women and children and filled even the bravest man with fear and anxiety.

One of these raids was in 1881. A fort was built and all of the ranchers and people living in nearby communities gathered in. Rettie says, “None were injured, but I will never forget the nights of terror I spent, thinking every sound was Indians coming to murder us. I never told of my fear, but I am sure the others were as frightened as I was. We would hear of ranchers and travelers being horribly murdered and didn’t know but what we might be next. I remember I would make light of my mother’s fears while at the same time I would be terrified. With the capture of Geronimo, the Indian trouble quieted down.”

The Ellsworth home was the gathering place for the young people for miles around. Rettie and her half-dozen grown brothers and sisters were a jolly group, and her parents made her friends welcome. Singing, reading, music, dancing, and [playing] games occupied the evenings. Good schools were provided, and the home influence was of culture and refinement and produced a family of excellent men and women.

In those days, possibly because of the responsibility placed upon them, childhood was short, and at the age of fourteen and sixteen, girls and boys were grown up, and around seventeen and nineteen assumed the duties of married life. When she was seventeen, Rettie promised to become the wife of Hans Hansen Jr., a fine young man she had known since coming to Arizona.

Loretta "Retta" Ellsworth Hansen. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Loretta "Retta" Ellsworth Hansen. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

On September 29, 1885, they and her brother Frank and his betrothed, Edna Merrell, started on their wedding journey to St. George, Utah. It took them six weeks to make the round trip. This is one of the breathtaking incidents Rettie relates of that trip: “One morning, way out on the desert, the boys were greasing the rear wagon, we girls, at the other washing dishes, found ourselves completely surrounded by large prairie wolves. We lost no time climbing into our wagon and the boys killed wolves as long as their ammunition lasted. It was a thrilling sight to see about fifty large wolves lined up like soldiers. At the sound of the gun they would jump back a few paces still facing us, then would step forward again. The howling of the wounded, and the firing of the guns finally frightened them away.”[65]

Upon the return of Hans and Rettie to Arizona, they lived in a small lumber room near the home of Hans’s father for the first year. During this time the Ellsworths moved to Mesa, Arizona. This almost broke Rettie’s heart, as the family was a very affectionate one. Especially did she miss her half of the twins, who were now nine years old and whom she had always loved and mothered.

In the fall of 1886, Hans and Rettie moved to another house. There they were very happy and especially so when their first child, a little daughter, was born on June 30, 1887. Here they continued to reside until near the close of 1888, when Hans received word of the death of his brother-in-law, Sanford Jaques, in Tempe, leaving a wife and four small children.

Hans took his family and went to the assistance of his sister Annie. They left behind all they had accumulated, including five cows and calves. These they never saw nor heard of again. Rettie was glad to be with her family again, and the Hansens remained in Mesa for two years. The latter part of 1890, they returned to Show Low and began life over again.

They both worked with a will and were very comfortably fixed with a nice log house and the necessities of life, when, in the Autumn of 1892, while the family was visiting friends about a mile away, their home, with all they owned in the world, was burned to the ground. They always believed it was set afire by Indians.

The one-roomed house they lived in the first year of their married life now offered them shelter again, but now instead of two, the family consisted of five, for three darling baby girls had been born to them.

They were alone at this place all that winter as Father Hans Hansen Sr. moved his family ten miles south of Show Low to a place they called Woodland. In the spring, Hans and Rettie joined them there. They built a small room with a dirt floor to live in until they could do better. Here their fourth daughter was born.

A two-room lumber house was built on their present location, which they homesteaded. Their fifth daughter was born in this house. No two of their children were born in the same house. The next move was into a three-room house nearby and here the five lovely daughters grew to womanhood.

In 1902, Hans Hansen Jr., who was born on August 24, 1862, in the southern town of Washington, Utah, was called on a mission for his church to Denmark, the birthplace of his parents, Hans Nielsen Hansen and Metta Katrina Adsersen. These “calls” are never compulsory, and though, at times, it is a trial of faith and always a great sacrifice to all concerned, they are seldom refused. With a love for the gospel that had done so much for his father’s family, Hans left his home, his five children, and the brave loving wife who bade him “God speed” with a smile on her lips and tears in her eyes and was gone for twenty-seven months.

The following is the story of his mission told from his lips:

In 1900 I attended conference in Snowflake where Apostle Francis M. Lyman was in attendance.[66] In this talk, he requested all men who had been on a mission to stand. When they sat down, he asked all of those who would like to go on a mission to arise. I was in the group that stood. While we were still on our feet, he made this solemn statement, “I promise you, in the name of Israel’s God, that He will open the way for every one of you to go on a mission if you sincerely want to go.”

I sat there with these thoughts flying through my mind: that big mound of debts that I had not been able to pay, leaving my wife and five girls alone on the ranch with no one to help run it, and the small wage that I always received when I worked away from home. I wanted to go on a mission, but it seemed like an utter impossibility. I told my wife, when I got back to the home where we were staying, all that had been said and done, and she said, “Then you are going on a mission.” I asked, “How, with all of the debts that I owe, could I ever pay them and make enough to keep me on a mission?” She said, “But Daddy, you heard Brother Lyman’s promise.”

When we got back to the ranch, I began to think seriously of the promise made at conference; I could not get it out of my mind for long.

One day I was up in the woods beyond my field. I found a secluded little spot, and there I got on my knees to pour out my soul to my Heavenly Father, explaining my dilemma, my indebtedness, and my inability to make any money, and if he wanted me to go on a mission, I needed help badly. I begged that the way would be opened for me to go on a mission.

That very spring I was sent for to come to the Scott ranch. Robert was my brother-in-law, and he and his brother George wanted me to use my team to make them some reservoirs. They contracted with me for this work on my own terms. I worked all summer making more money than I had ever made before. I was through before winter and had enough money to pay all my debts and to allow for some badly needed clothes.

Next spring, Mr. [Bill] Morgan and Mr. [Jim] Porter wanted me to make some reservoirs for them which I gladly did.[67] At the end of the summer I had enough money to pay for a twenty-seven month mission in Denmark.

I had to leave my family on the ranch alone without funds. My wife felt that they could take care of themselves. I finally arranged with a young Danish boy to stay and run the ranch. But the most severe drought the country had ever known dried up the spring that watered my place and not a thing could be grown for the two years I was gone. The girls had to haul water from a creek a mile from the ranch.

I left for Denmark on the 5th of December 1902 and returned on the 16th of March 1905.

My first companion was an old man that was extremely hard to live with. No one else could tolerate him, so I was given the task of living with him or having him sent home, so I stuck it out with him until his release came.

I was studying hard to learn the language and needed help, but the old fellow refused to answer my questions or help me in any way. He refused to go tracting with me so I was left to work it out alone.

I was out tracting one day and unknowingly entered a saloon where men were standing at a bar. I hurriedly passed out some tracts and left without a word. When I got outside I said, “Father in Heaven, surely I can do better than that.”

The next place I entered was the home of a minister. He had an open Bible before him, and he was arguing with his daughter and a friend. I had not been there long until they started asking me questions. I was answering all of their questions, and they seemed satisfied. Finally, the daughter said, “Well, you are a minister and are you going to let that man get the best of you like that?” The father said, “You are a minister’s daughter, can you do any better?”

When I had been in Denmark about a year and a half, I was having a great deal of trouble with a hernia that eventually put me to bed. My companions had to leave me there alone, and I lay there wondering what I was going to do. I didn’t have the money for an operation, so I took my troubles to my Heavenly Father and told him I needed help.

The President of the Mission heard of it and offered me an honorable release which I refused and sent word back that I was finishing my mission.

Later in the day, while I was lying there alone, the door opened, and my father, Hans Nielsen Hansen, who had died in 1901, walked into the room, bent over my bed and pushed my clothes apart and put his short, chubby hands over the hernia and pushed very hard. I said, “Oh Daddy, you are hurting me.” There was no answer, but a constant pressure until I felt something slip back into place. He straightened up and said, “Now you will be all right in a few days,” and walked out of the room. They were the only words he had spoken.

In a few days, according to his promise, I was back to work again, well and strong to finish my mission. I returned home on the 16th of March 1905, with twenty-five cents in my pocket.

During this time, Rettie and the girls (the eldest, Gertrude, was fifteen when her father went away) managed the affairs at home so well that he returned free from debt. Rettie had taken in washing and sewing, boarded school teachers in the winter, and taken the responsibility and work of providing for the six of them, each happy to assist when not in school—but their education [could] not be neglected.

It was a joyous occasion when the family was again reunited. Life took on the usual routine when in June 1911, fire again robbed them of all their earthly possessions. Hans was away on business, and Rettie, who was now the only midwife and nurse in those parts, was called out by sickness when the fire was discovered, but too late to do anything.

“Friends and neighbors from far and near donated toward our clothing and to start a fund for another house,” recalls Rettie with grateful remembrance.

A one-room lumber house was built for a storeroom and also for a bedroom for their adopted son. In it was all of his clothing, household supplies, windows, doors, and hardware for the new house, two saddles, and various other things, when fire, for the third time, took its toll. The frame building and all its contents were in ashes in a few minutes. They managed to save the tents in which the remainder of the family was camping. These continued to be their only dwelling places until the much coveted home was completed, six years later.

Gertrude went to Weber Academy, in Ogden, Utah, while David O. McKay was President; she attended school for two years, 1906 and 1907.[68] While she was there, Rettie had to go to Ogden to undergo a very serious operation. She was gone for two months, returning much improved in health.

The winter of 1908 and 1909 was spent in Snowflake where the girls attended high school. This was a very happy time for Rettie as she had so many friends there and all of her children were with her.

In 1910, two of her daughters married and moved to the Salt River Valley. In 1912 and 1915, two more were married and left home, leaving only the baby girl, Georgia. Her desire was to become a school teacher. Her first school was in Vernon, Apache County, in 1922. She taught there two years. She was teaching in Taylor in 1924 when one of the children in her room came to school with diphtheria. Georgia contracted it and went home. In a week, [on] October 17, she died. Her friends were numbered by her acquaintances who joined her parents in their grief at her untimely death, which her mother never entirely recovered from.

“For many years in our first married life” Rettie says, “we had a hard time to keep the wolf from the door. The last fifteen have been much better.” They have a beautiful country home with every modern convenience. An air of comfort, culture, and refinement permeates the place. Choice pictures adorn the walls, easy chairs, a bookcase filled with the best books, a radio, birds, and flowers make the place a veritable paradise. It has not come without work and patience. Hans has always been a hard, conscientious worker—this lovely home is entirely the work of his own hands. He has a rule that he strictly adhered to—never to buy anything until it can be paid for.

For thirty-five years [meaning this was written in 1937], Rettie has been a nurse. She says, “I have taken care of all kinds of sickness and have assisted over three hundred babies into the world. Have gone in all kinds of weather, walked two miles to a car, taken off my shoes and stockings and waded streams of water, and since my rheumatism is so bad I have gone when I had to have a man on each side of me to help me into the car. Never have I refused to go if I were able. Have done this without pay in the majority of cases, but have always been glad and thankful to be of some service in the world.”

She and her husband have grown old gracefully and beautifully together. They were beloved by all who knew them. It is such as they that make earth a Heaven and give all a desire to strive for the same love, peace, and contentment.

Ellis and Boone:

Although this biographical sketch was based on an FWP interview, Loretta Hansen herself was committed to personal and pioneer histories. She began a diary on March 19, 1918, and wrote an autobiography while in Lavern, California, December of 1925.[69] Clayton did not update this sketch for PWA except by adding the long quote from Hans’s mission. Loretta Ellsworth Hansen died on March 29, 1940, and Hans Hansen died on October 7, 1953; both are buried at Lakeside, the town they worked so hard to build.

For her birthday in 1925, Rettie Hansen received a birthday poem from Roberta Clayton. Part of this poem tells about people from outlying communities coming to Snowflake for quarterly conferences that were not only a time for church services but also were a time for renewing friendships: