G

Roberta Flake Clayton, Ruth Goodman Tilton, Catherine Ellen Camp Greer, and Emma McClendon Martineau, "G," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 203-227.

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Rozilpha Stratton[1]

Birth: June 24, 1854; Cedar City, Iron Co., Utah

Parents: Anthony Johnson Stratton[2] and Martha Jane Lane[3]

Marriage: George Abel Gardner;[4] July 24, 1872

Children: Anthony Layne (1873), Martha Elizabeth (1874), Harriet Rosabell (1875), Mary Emaline (1878), Charles Abel (1879), George Franklin (1882), William Edgar (1884), Albert Riley (1886), Rozilpha (1888), Betsey (Betty) (1890), Martha Jane (1893), Penelope (1895), Joseph Victor (1897), Lucinda (1901)

Death: November 30, 1929; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner was born June 24, 1854, at Cedar City, Utah. The house in which she was born was a log one. There was a severe storm on the night of her birth, and her father had to spread a wagon cover over her bed to keep it dry. She was the fifth child of Anthony Johnson Stratton. Her mother was Martha Jane Lane.

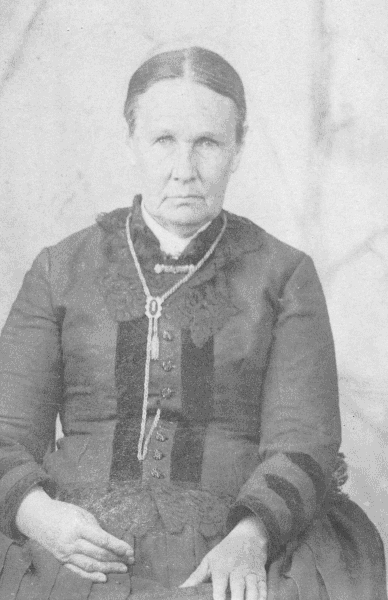

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

The first move of the family after Rozilpha’s birth was from Toquerville to Virgin City, Utah. She remembers her father farming with an ox team. He always had a good farm and took special pride in keeping it in good condition. Their principal crop was fruit which they took to northern markets to trade for household necessities. At first, grain did not grow successfully in this district, but later the farmers procured a more hardy variety and raised the wheat for their bread. They did their threshing with flails or with horses by the tramping method. They raised cane and made their own molasses. When the molasses season was ending, they would cut up their fruit, put it in the vats where the molasses was made, and make their preserves. Oftentimes all the women in town would join on these occasions, and thus the preserving season was made into a holiday. Much fruit was dried and sold to the nearby mining camps. Large, luscious melons were produced in great abundance. Cotton was raised, picked, carded, spun, and woven into cloth. It was dyed with roots and barks of trees and herbs. Peach tree leaves made a very satisfactory yellow. For years, they had a homemade loom, but later on got a patented one.

They raised gourds which were used in the kitchen as receptacles for holding their cereals. Wheat straw was gathered and made into hats. Oftentimes the girls of the family would have to go to bed while their one dress each was being washed and made ready for Sunday, or for a dance. Rozilpha was fourteen years old before she had her first pair of shoes. Early in life she learned to knit her own stockings and became so proficient at it that she could widen, narrow, and finish toe and heel without having to look at her work.

Her schooling was very limited. They only had one slate, [for] spelling and arithmetic, which was used by all the family. They would get soft rocks from the mountain and use for slate pencils. The first book she ever had was made by the teacher and was a shingle with ABCs on one side and figures on the other. This had to be carefully preserved to be handed down to the next member of the family. To them writing paper was unknown. Rozilpha was a grown girl before she ever saw colored paper.

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Rozilpha Stratton Gardner. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Their church-house was a bowery, and they used it for several years before it had a floor in it. On account of the Indians they lived in a fort for years. The men took their turns standing guard against the Indians. She remembers seeing two white women and two men brought in murdered by the Indians. The people of this little community had many good times and did not worry about their financial conditions. They would throw off their worries of the day and meet often together in the evenings for parties and entertainments. There was neither rank nor distinction; everyone was treated as an equal. It was at a peach-cutting bee that Rozilpha Stratton met her future husband, George Abel Gardner. To him, she was just a little different from the other girls. He asked her name. They told him, “Rose.” Immediately, he thought of her as a flower and how nature was helping each petal to unfold into womanhood. To make a long story short, he walked home with her that evening. They often went to dances together, taking vegetables to pay for their tickets, and danced barefooted on the floor. At a pioneer celebration on the 24th of July, these young lovers surprised the audience by staging a wedding, the occasion being a double ceremony as their two friends were married at the same time; Charlie Brewer and Suzanna “Susie” Dalton (also Arizona pioneers), became bride and groom.

After the ceremony they moved to Mountain Dell and began housekeeping in an unpretentious way.[5] Their home was an adobe house, but being a gardener by nature as well as by name, George soon had a good farm and orchard. Their surplus fruit was hauled to the surrounding towns and traded for whatever they might be able to use.

They lost their first two children, who died in infancy. But three others came to bless their home while they were still living in Mountain Dell.

They received a call from Brigham Young to come to Arizona to locate and build new town sites. A call to Arizona necessitated immediate preparation and a great sacrifice. They arrived at Snowflake December 18, 1881.

By hard work, economy, and thrift, they were able to sustain themselves and their family of nine children. Her husband met with an accident which necessitated the amputation of his leg, and for more than a year he was unable to work. They often referred to the kindness of friends and neighbors during this time and were deeply grateful for all of the help given them. In due time, health and comfort were given them to carry their responsibilities.

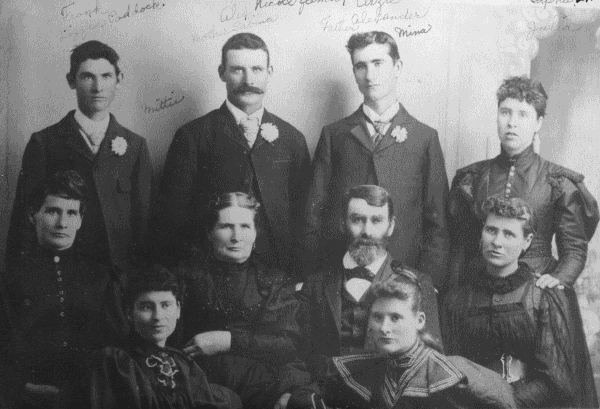

Family of George Abel and Rozilpha Stratton gardner; front row (left to right), Betty and Zilpha; middle row, Riley and Edgar; back row, Frank, Charles, Mary, and Harriet. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Family of George Abel and Rozilpha Stratton gardner; front row (left to right), Betty and Zilpha; middle row, Riley and Edgar; back row, Frank, Charles, Mary, and Harriet. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Because of Rozilpha’s cheerfulness and love of service, she was many times called out to help with the sick. She early found that there were nearly always those in need of help, and it was characteristic of her to sing “There’s a Good Time Coming.”[6] She would never allow her children to speak disrespectfully of anyone. She taught them, by example, principles of uprightness and morality. For many years she was a sufferer of tic douloureux, or facial neuralgia and spent hundreds of sleepless nights. All this she bore without complaint. Perhaps the most strenuous ordeal through which she was ever called to pass was during the seven months before the amputation of her husband’s leg. During this time, she never removed her clothes for a night’s rest. On July 28, 1895, she gave birth to a daughter [Penelope] and her husband’s leg was amputated the next day.

It was during one of her sieges of excruciating pain that Rozilpha met with an accident that resulted in her death, November 30, 1929.[7] A beautiful funeral service was held in her memory. Many of her old friends and neighbors paid loving tribute to her unselfishness, devotion to duty, and loyalty to every good cause and to her family.

Ellis and Boone:

Arizona’s pioneer women, as do women of all ages, passed through times this author called “strenuous ordeals.” The story of the amputation of George Gardner’s leg began with a three-story fall from scaffolding when he was working on a house for James M. Flake (who built the only three-story house in Snowflake). After weeks of suffering, Dr. Joseph Woolford amputated the leg and then began the long period of recuperation.[8] Gardner became so weak that his spirit left his body; he saw deceased friends and family but was told “that his mission on earth was not complete.” Nellie Merrell wrote:

Kind friends were many and did everything they could to relieve his family, who were having a hard struggle. The older son, Charles, was not yet old enough to take the responsibility of the farm.

A few nights after the amputation, kind neighbors gathered both food and clothing and left it on the door step. They brought their guitars and serenaded them in the good old-fashioned way. I have often heard them say that never before had music sounded so heavenly, it was like the singing of angels and tears of happiness came to the eyes of the family in thankfulness to the kind hands that had brought kindness and relief.[9]

George Gardner lived with a wooden leg more than thirty years; he died November 4, 1927.

Anella Stanton Lytle Gibbons

Unknown Family Member

Maiden Name: Anella Stanton Lytle

Birth: November 25, 1888; Eagar, Apache Co., Arizona

Parents: William Perry Lytle and Lucy Atchison

Marriage: Lee Roy Gibbons;[10] April 1, 1921

Children: Rendol Lytle (1922), John Elwood (1925), Lee Stanton (1927), Wanda N. (1928), Donna Jean (1930)

Death: August 3, 1951; Highway 66, Coconino Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Anella Stanton Lytle was born November 25, 1888, at Eagar, Arizona. She was the youngest of twelve children born to Lucy Clarinda Atchison and William Perry Lytle. Despite protests of some of the family who thought she shouldn’t marry a man fifteen years her senior, Anella and L. R. Gibbons were married on April 1, 1921, in the Salt Lake Temple.[11] From this union five children were born: Rendol Lytle, John Elwood, Donna Jean, and two who preceded her in death.

Anella was called “Aunt Nell” by everyone who knew her. The fineness of her character and the sincerity of her life appealed to all.

Anella Lytle Gibbons, Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Anella Lytle Gibbons, Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

She entered into every phase of community life, be it political, social, or religious. She considered her franchise a thing of great value and served her county both as recorder and treasurer. During World War I, she served as secretary to the local draft board. She was a teacher in the schools. Of all the interests that claimed her attention, none received such wholehearted support as her church. Aunt Nell was deeply religious. Hers was the kind of religion that was translated into deeds of mercy and kindness. In every phase of church work, she rendered valiant service. Trudging through the dark with her flashlight, she would be the first one to choir practice and usually the first to Sunday School, Relief Society, church [sacrament meeting], and Mutual. For eight years, she was Relief Society president of the St. Johns Ward. She served as secretary of the Sunday School and as a worker in the YWMIA. At the time of her death, she was president of the Stake Relief Society.

Aunt Nell was gifted in singing, having a very true alto voice. She did lovely painting on chinaware. Her poems were written to give tribute or to bring comfort to people.

While living in Eagar, Aunt Nell and her brothers and sisters walked two and a half miles to church and to school. Most of her people were not very well off financially, many of them quite poor. She really loved them and was loyal to the people of Eagar. The children used to tease her about her home town and say, “Oh, those people up at Eagar are just a bunch of Communists.” All excited she’d answer, “Listen, you could learn a lot from those people.”

She detested anyone “putting on airs” or thinking they were better than someone less fortunate. She had compassion for anyone less fortunate and was always helping someone. It was to her you ran for help when you thought the baby was choking to death with the croup or the older boy was burning up with a stubborn fever. People came to her with their problems because of her understanding and sympathy. Many times she has said, “It isn’t where you are but what you are that counts.” The kind of house she lived in and material things in life were unimportant to her compared to living the gospel.

Anella Lytle Gibbons, Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Anella Lytle Gibbons, Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

She loved people but she especially loved little children, and because of her love for them they responded to her. She had a box behind her bedroom door full of odds and ends (empty spools, boxes, etc.) that delighted them.

Her devotion to duty and the Church were outstanding. She instilled dependability in the hearts of her children and taught them the importance of service to others and loyalty to the Church authorities.

Never a day passes that she is not sorely missed. Her memory will be cherished throughout the years. As a family, we honor the example she set before us. Friends and neighbors pay tribute to her. They remember her attending all social events, at the dances, sitting by the piano tapping her foot to the music. She never met a stranger; her greeting made each one feel important.

Her home had a warm welcome atmosphere at all times. And along with her loving counsel and advice, the memories will live on forever.

Ellis and Boone:

Annella Lytle, “a prominent lady from Eagar,” was thirty-two years old when she married Lee Roy Gibbons as his second wife. They lived together for twenty-one years, raising his children and their three and participating in all aspects of the St. Johns community. In 1933, Lee Roy was elected as Apache County treasurer and served four years. Then, he was in an automobile accident eleven miles northwest of Concho and died on August 25, 1942, of his injuries. Still a relatively young woman in her fifties and with her youngest daughter only twelve years old, Annella considered her options. In 1944, she ran for Apache County treasurer, won, and served in that capacity for many years. On August 3, 1951, Annella herself died in a two-vehicle automobile accident fifteen miles west of Winslow; she was buried in St. Johns.[12]

Armitta Nicoll Gibbons

Unidentified Offspring

Maiden Name: Armitta Nicoll

Birth: September 8, 1871; Washington, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: Alexander Nicoll and Sabina Ann Adams

Marriage: Lee Roy Gibbons;[13] March 16, 1893

Children: stillborn son (1894), Pauline (1895), Sabina (1897), Rizpah Genevieve (1900), LeRoy (1902), Armina (1906), Armitta (c. 1908), twins Leona and daughter (1913), stillborn son (1917)

Death: November 20, 1918; St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

The Nicoll twins, Armitta and Armina, were born September 8, 1871 in Washington, Utah. They were the eighth and ninth children of Sabina Ann Adams and Alexander Nicoll. In 1879 the Nicoll family was called to settle in the new Eastern Arizona Stake. They moved to Woodruff, Salem (one mile north of St. Johns), and finally to St. Johns, Arizona.

Mother said, “We never went to bed until the dishes were done. We could entertain our friends as much as we liked but had to leave the dishes and kitchen clean. No matter how late we were up to a party or dance, we had to be up at the usual early hour to do our part of the work.” Armitta and her brothers and sisters were taught to do their share and to do it well.

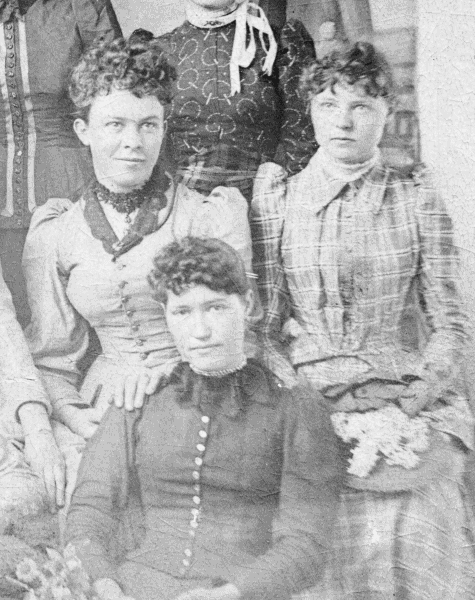

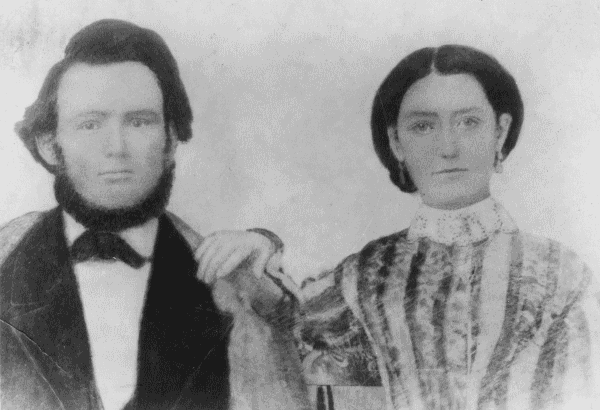

Armitta Nicoll and Lee Roy Gibbons, 1893. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Armitta Nicoll and Lee Roy Gibbons, 1893. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Alexander and Sabina Nicoll loved music. An organ was brought from [bought by] their father for the twins’ birthday. The twins paid for their music lessons by doing housework. Armitta played the organ for church and later for the dances. It was said that “Mittie didn’t miss a beat and the organ sounded sweeter when she played it.”

The family was broken hearted when Armina ran away and got married. To help Armitta forget her longing for Armina, Alexander brought her a pure white lamb which she loved and cared for. Another time he brought a beautiful doll with light brown hair and blue eyes. Sewing for this doll and loving it was also a comfort to Armitta.[14]

March 16, 1893, Armitta and Lee Roy Gibbons were married by civil authorities. Their mothers accompanied them to the Logan Temple where they were married for time and all eternity.

The first child was a boy and stillborn. Pauline was born December 25, 1895, Sabina was born December 17, 1897, and resembled her parents. A third girl, Rizpah Genevieve was born May 31, 1900. The long looked for boy, LeRoy Jr., was born June 10, 1902. When she failed to have twins, Armitta named her fourth girl Armina, and the fifth girl Armitta. Then in 1913, the twin girls were born, only Leona lived and the other little girl was dead at birth. A beautiful ten-pound boy was born dead one year before Mother died.

Armitta had a great capacity for love. She grew up in a home surrounded by love. She loved her parents and twin sister very dearly. She was devoted to her own children and husband. All the love and effort that could be put into a home was put into hers. Her every thought was for the care of her family. She loved her neighbors and continually cooked tasty food for lonely ones. She shared her bounties with others.

She was an artist in many fields, and a perfectionist in everything she did. As a young woman, she had played the organ and sang in the choir. After her children came she gave this up but did play in the mandolin and guitar club. Her guitar was a gift from LeRoy. She played at home daily for the children. We all spent happy hours singing about the piano. When we were very young, we had a song or two each morning and then stepping happily to a little march we went to our work.

Natal family of Armitta Nicoll Gibbons. Front row (left to right): Armitta Nicoll Gibbons, Armina Nicoll Eaton; second row: Elizabeth Ann Nicoll Paddock, Sabina Ann (mother), Alexander (father), Julia Nicoll Greer; third row: Frank, Alexander Jr., Arza, Orpha Nicoll Greer; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Natal family of Armitta Nicoll Gibbons. Front row (left to right): Armitta Nicoll Gibbons, Armina Nicoll Eaton; second row: Elizabeth Ann Nicoll Paddock, Sabina Ann (mother), Alexander (father), Julia Nicoll Greer; third row: Frank, Alexander Jr., Arza, Orpha Nicoll Greer; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Armitta was not a regular church goer. She went when she was not too weary, but we children were always tastefully dressed and were sent to Sunday School each Sabbath day. On coming home, we were fed and our Sunday clothes carefully put away, but we could not play. She taught us to love God and to honor his Sabbath Day completely.

One time while we children were playing in bed with Leona, six months old, Mother said as tears rolled down her cheeks, “I will never live to raise these children. It just doesn’t seem right.”

When the Armistice was signed November 11, 1918, Armitta went in the family Model A to the big bonfire celebration. A week later she said, “I feel a little better. I’ll eat with the family today.” She suffered a stroke while at the dinner, which paralyzed her lower limbs. She was carried to her room. After two days of unconsciousness, she died November 21, 1918.[15]

Armitta’s spirit was highly developed. After her passing, her children came to realize that her world had always been more spiritual than material. She understood so many things never perceived by others

Ellis and Boone:

Armitta Gibbons was one of the women who helped music flourish in St. Johns. LeRoy and Mabel Wilhelm wrote, “Armitta, one of the Nicoll twins, and Alice Platt were seen playing the piano many times for dances as well as for Church. They were pupils of Anna L. Anderson, a talented musician and teacher who gave St. Johns a reputation of knowing and playing the best in music.”[16]

These same musical talents were passed down to her son, LeRoy Gibbons Jr., who taught music in Holbrook for many years. His philosophy reportedly was, “Teach a boy to blow a horn, and he’ll never blow a safe,” undoubtedly a response to those who turned to crime during the Great Depression. His award-winning marching bands helped many teenagers through these years. One of his students, Zena Beadle Hunt, wrote, “If it weren’t for Mr. Gibbons, Holbrook would have been a pretty dull place. No library, no park, no organized ball games, no bowling alley. But the school music program gave us all something to do.”[17]

Christianna Glass Gilchrist

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview

Maiden Name: Christianna Glass Gilchrist

Birth: January 20, 1862; Boggstown, Shelby Co., Indiana

Parents: John Gilchrist and Sophia Christianna Monfort

Marriage: none

Death: December 19, 1945; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Las Vegas, San Miguel Co., New Mexico

In a cozy little home near the capitol grounds in Phoenix, Arizona, lived a pioneer woman of unusual ambitions and achievements. She was Miss Christianna Glass Gilchrist, the daughter of Reverend John Gilchrist and his wife Sophia Christianna Monfort. She was born January 20, 1862, in Boggstown, Shelby County, Indiana. “It is only a wide place in the road,” says Miss Gilchrist.

Her father came from Scotland with his parents when only seven years of age. Through her mother, she is of Holland, Dutch, and French descent. When a young man, Mr. Gilchrist’s thoughts turned to the ministry, and he was a pastor in the Presbyterian church for many years prior to his death, which occurred when Christianna was only fifteen months old, leaving his wife to rear and educate their five children. Only by the strictest economy and most careful management was this accomplished.

The family owned their own home. Never in the stress of providing for their physical wants did the little mother neglect the spiritual and educational ones. Of her three brothers, who all became Presbyterian ministers, Miss Gilchrist says her mother never had a moment’s anxiety.[18] Each of the children was given a college education.

Christianna Glass Gilchrist. Photo courtesy of Arizona Historical Society, Tucson.

Christianna Glass Gilchrist. Photo courtesy of Arizona Historical Society, Tucson.

The school house still stands in Greenfield, Indiana, where little Christianna began and finished her grade school education. James Whitcomb Riley and his older brother John were schoolmates of hers, and John was a great friend of her brothers; he was at their home as though it were his own.[19] Because of the harum-scarum irresponsible ways of young James he did not find such a warm welcome at the Gilchrists’.

Christianna laughingly says, “There never was but one person homelier than Jim Riley and that was his brother John.” John, too, used to write poetry, so, also did Miss Gilchrist until she was fifteen; then she decided there was enough of that kind of stuff being written, and at seventy-seven she thought that was pretty wise reasoning for a girl of that age.[20]

Her happy school days passed in the beautiful land of Indiana. Though she was unable to live there, she has never ceased to love it with an undying emotion. Especially does she recall the beauty of the surroundings of Hanover College, from which she graduated.[21] Located on high bluffs overlooking the Ohio River, it commanded a view of the rolling hills and valleys below that remains a picture in her memory. The teacher from whom she probably gained the most inspiration was Lee O. Harris, an educator of high standards, who used to write with James Riley.

Her college days were spent in hard work. Natural science was the study she specialized in—teaching was to become, of necessity, her profession. Consequently upon her graduation at the age of twenty-three she accepted a position in an academy in the San Luis Valley in Colorado. Here she taught for eight years. Her family had moved west; also, her two eldest brothers became missionaries under the Presbyterian Board of Missions. Christianna spent much time assisting them with their work.

Due to the strenuousness of her work, together with the malaria in her system from the swamps and marshes of her homeland and the high altitude of Colorado, her health broke. At the school, she had taught in any of the grades and wherever she was needed, using up her strength, “burning the candle at both ends.” Then came a few years in search of the priceless boon of health. This took her to northern New Mexico, then to California for a year and a half, then back to New Mexico. None of these places satisfied Miss Gilchrist, nor was there a great improvement in her health. Through the Presbyterian minister, Rev. Preston McKinney, who was a great friend of her brothers, she was induced to try the climate in Arizona. This was in 1900.[22] First she stayed in Prescott, at that time a lively, bustling little town of about 8000 inhabitants. Mines were being worked nearby and the “mile high city” was very prosperous.

With cold weather, Miss Gilchrist came to Phoenix. Of it she says, “It was a lovely little town.” Neat comfortable homes, flowers everywhere, clean streets, water in the ditches which were canopied by magnificent fig trees. The Capitol building was being built, the street car lines extended as far west as they do now. Most of the homes were in the vicinity of the capitol. The Mexican population lived picturesquely in their adobe houses or under the trees along the banks of the ditches. She didn’t mind the summer heat, and greatly enjoyed the mild winters, such a contrast to the ones she was accustomed to.

Many trips have been made by Miss Gilchrist, both to the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards, and to her old home, but she always came back to Arizona. Finally, she bought the home in which she lived until she died, December 18, 1945. Different members of her family have visited her. One of her brothers spent three winters with her before his death.[23] Her sister, who passed away in 1936, lived here with her for fifteen years.[24]

When asked why she had never married, her eyes twinkled as she answered, “Never could be serious long enough, was too busy having a good time to be tied down.” “You must have had plenty of admirers,” was ventured, to which she replied, “Oh, there were some who thought they loved me well enough to take the responsibility of my board and keep, but I laughed them out of it.” Life continues to be an amusing experience to her.

For five years after her graduation the members of her class kept in touch with each other. There were eighteen of them, one girl having died the first year, the other seventeen kept a round robin letter circulating between them until during the Russo-Japanese war one was lost on its way to a member who was a missionary in Korea.[25] The custom was not resumed until after the class reunion. She and her brother who graduated at the same time were not present because of ill health.

For eighteen years after coming to Phoenix, Christianna was very active in the Associated Charities, doing uplift and relief work. She went into homes of poverty and distress, trying to relieve the conditions. There were many transients who might have been self-sustaining and respected citizens in their own communities, but were handicapped here by ill health or lack of employment. “You can only do so much for people—the rest must come from themselves” is her philosophy.

Perhaps the most outstanding work of Miss Gilchrist was her interest in the Missionary Society of her church, which she organized and was for many years president of, and at the time of her death was the oldest surviving one in the Presbyterian church in the city.

When asked if she was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, she answered that she was not—that though her cousins on both sides of the family were, so she could qualify, she didn’t have time. She is a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Though poor health prevents her from attending church very often she was intensely interested in everything. She loves to study, and says if it were possible she would continue to study natural science, especially geology, under a competent instructor. Her cheerful little home with birds, flowers, a large library of volumes, and the air of refinement and culture was a fitting place for the little old lady that graced it.

Among her possessions were many valuable heirlooms. She had two blue and white hand-woven coverlets and another of handsome linen, elaborately embroidered in white employing twenty-seven different kinds of stitches. All three of these were more than 100 years old.

With tuberculosis being a leading cause of death in the United States, Christmas seals were introduced in 1907 as a way to raise money. These stamps have been issued by both national organizations (such as the American Lung Association) and local entities like these stamps from Phoenix. The design often did not change from year to year but the colors did; clockwise from top left: navy blue on silver foil, purple on silver foil, black on gold foil, and brown on mustard. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

With tuberculosis being a leading cause of death in the United States, Christmas seals were introduced in 1907 as a way to raise money. These stamps have been issued by both national organizations (such as the American Lung Association) and local entities like these stamps from Phoenix. The design often did not change from year to year but the colors did; clockwise from top left: navy blue on silver foil, purple on silver foil, black on gold foil, and brown on mustard. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Perhaps the article most valued by her is a wall panel woven by two old uncles of her father almost a century ago. The pattern consists of doves, fig leaves, pansies and geometrical designs in the border. The colors are blue and white and it is reversible.

Miss Gilchrist had hosts of friends especially among the younger people whose problems she seemed to understand. She carried on a large correspondence with absent ones, and spent her time in reading, visiting, and doing her own housework with the aid of a woman who came in once a week.

With a keen sense of humor as well as one of unselfish service, the sunset of her life found a woman who lived and gave of her life to help others to find a better way. She was truly a beautiful example of Christian womanhood. She died December 18, 1945.[26]

Ellis and Boone:

Christina Gilchrist moved to Phoenix in 1900, and in November 1904, local churches, lodges, and businesses formed the Associated Charities of Phoenix. The creation of this group was in direct response to the large number of indigent people with tuberculosis in the Salt River Valley. Tuberculosis was found in epidemic numbers throughout the U.S., and the only “cure” was moving to a dry, warm climate like that of the Southwest. Although many health seekers initially came to Arizona with enough money for their care, often their resources were soon exhausted. More affluent consumptives rented houses or stayed at resort hotels or sanatoria such as the Desert Inn Sanatorium or the Ingleside Club, but the poor ended up in tent camps at the edge of cities.[27] As Bradford Luckingham wrote, “For many of [these consumptives], the desert proved to be a death warrant rather than a cure. In short, the sick poor existed as best they could, often without food, clothing, or care.”[28] More Arizona deaths in the early twentieth century were from tuberculosis than from any other cause.

In the Associated Charities’ published health report from 1915, it stated that “during the year from April 1, 1913, to April 1, 1914, [they] received 690 applications for relief from indigent consumptives, expending on these about $4,000 (about 30 per cent of their total available funds). Railroad fare home took about one-fifth of this sum. The Phoenix authorities estimate the annual migration of consumptives to Phoenix is about 1,200, including all classes. Their experience led them to believe that most of the indigents did not become such until after six months’ stay.”[29] Christianna Gilchrist worked hard to solve the budget problems that she always found when caring for indigent tubercular visitors. Luckingham wrote, “Through example she inspired many Phoenix men and women to devote time and money to the problems of poor health seekers and others in need of assistance.”[30]

It seems likely that both Christina Gilchrist and her brother Frank suffered from tuberculosis, although he died as a young man and she lived to be eighty-three years old. Both are buried in the International Fellowship of Odd Fellows Cemetery at Las Vegas, New Mexico.

Annie Maria McRae Goodman

Ruth Goodman Tilton

Maiden Name: Annie Maria McRae

Birth: February 3, 1873; Charleston, Wasatch Co., Utah

Parents: Joseph McRae and Maria Taylor[31]

Marriage: Joseph Thomas Goodman; June 12, 1893

Children: Ruth (1894), Alma Donald (1895), Joseph Edwin (1897), Howard Arthur (1899), Alexander (1900), Annie Alice (1902), Morten McRae (1904), son (1907), Glen George (1908), Mabel Theresa (1910), Frank Kenneth (1913), Basil Harry (1915), Orson Taylor (1917)

Death: April 21, 1948; St. David, Cochise Co., Arizona

Burial: St. David, Cochise Co., Arizona

Annie Maria McRae, eldest daughter of Joseph McRae and Maria Taylor McRae, was born February 3, 1873, at Charleston, Wasatch County, Utah. The weather was very cold; snow had drifted against the house above the height of the windows. Her father had to go to a neighbor’s to borrow a team of large horses in order to bring a midwife who assisted at the birth. Her grandmother, Ann Wicks Taylor, had been with her mother since before Christmas and had stayed for some weeks to help in caring for the baby. Her parents were very pleased that the baby was a girl as they had three sons and their eldest girl, Eunice Ann, named for both grandmothers, had died when less than two weeks of age.

Annie Maria was named “Annie” after Annie Wells Cannon, whom the mother had cared for as a baby when she lived in the home of Emmeline B. Wells, and “Maria” after her mother.[32] Her younger sister, Mary Jane, was also born in Charleston, which their parents often referred to as “Provo Valley.”

At the October Conference in 1876 held in Salt Lake City, Joseph McRae and family, and a number of other families from Utah and Idaho, were called on a mission to Arizona by President Brigham Young to help locate in and settle Arizona. She, her parents and three brothers, Joseph Alexander, John Kenneth, and George Edwin, and baby sister, Mary Jane, left Charleston with two wagons and teams. They loaded the wagon with groceries and necessities to last until they reached their destination. It was hard for the mother to leave her home as it was the first they had been able to own since going to Charleston. Their first child, Eunice Ann, died as a babe. She and the boys were all born in Salt Lake City.

Annie remembered a few small incidents that happened on the journey to Arizona. When they reached Corn Creek and camped for the night, her father pitched the tent and put up a small cook stove, which he did each night.[33] He placed her near the stove in her little chair, but as the fire got hot, the teakettle boiled over into her lap, scalding her very severely on the legs. She did not remember what they did for the burns, but they continued [traveled on] after some delay.

When they reached the Salt River, the whole company camped, and the men went to work building ditches and trying to raise some food. The climate was very hot so they put a brush shed over each tent. The women and children would go to the river to swim and get out of the terrible heat. One day a large Gila monster came and frightened them all very much. Annie almost drowned, but a lady came and pulled her out.

The family, with part of the company, left the Salt River and moved south. When they reached Tucson, they heard of some work in the Santa Rita Mountains where they went. They lived there until fall. The children played with some Mexican children. Later they moved to the west side of the San Pedro River where they stayed and spent Christmas living in tents. She remembered the doll old Santa brought her, a rag doll with a red dress made out of material like her own. They each got an apple tart and some raisins, but she does not remember what articles the others received.

There was a man who lived near who had a lot of goats. He seemed cruel as he would throw the goats from one pen to another. They had goat meat to eat, and when her sister was old enough to be weaned, all the milk they gave her was goat’s milk, which she did not relish.

The men built a rock fort on the east side of the river, and they lived there for some time. Everyone had chills and fever and were very sick, especially the mother.

Next they moved to the Huachuca Mountains. Her brother Charles was born there. On her sixth birthday, her father gave her a small dresser that he had made and which was a novelty at that time. The mother taught the neighbors and her own children in a home school. They had very few books or paper. She taught them to memorize hymns from the LDS songbook. Some she especially remembered were “O My Father” and “O Stop and Tell Me Red Man.”[34] After they came back from the mountains, she and Sister Susan Curtis taught school in their home.[35] When Cochise County was formed, they had teachers from farther away: Miss Felter first, then Miss Vinotti, and then a Miss Buster.[36]

In 1882, they built a county school building of adobe which was quite large. They had two teachers. By this time there were many new families so dances, plays, etc. were held in the school building. They all took part and enjoyed life very much.

On April 30, 1882, they celebrated May Day as May 1st was on a Sunday. Annie was crowned Queen, which was quite an event in her life as all the girls hoped to be the one chosen.

Annie’s parents gave her all the advantages possible at that time to gain an education, which she gladly accepted. Her brilliant mind quickly read anything, but the finest literature she enjoyed most. A lover of beauty was she and was ever on the alert to find it—in a flower garden, or picture in a magazine, or just anywhere that such could be found. How she longed for a lovely home. No one ever heard her complain at the lack of it, but she would always imagine the home she would someday have—bright colors where there should be bright and delicate, pale colors where they belonged—she could dream, couldn’t she? For all this was just a dream. In reality, she had very little of this, for the money earned was used to feed and clothe hungry, naked babies which came one by one.

Her ideals were of the highest. Nothing vulgar or low appealed to her fine nature. How she liked beautiful clothes, but precious few were hers. At no time was she unclean in her dress; always said she would rather have new underwear than a new dress. Also, if her clothes weren’t good, she stayed at home, for she must look her best when she went anywhere.

She was always true to her faith and took an active part in church and community affairs. Her parents had seen that she learned to play the organ, and she was the leader of the ward choir for years. Then in Sunday School and Primary and in YLMIA, she was secretary and teacher. For many years, at two different times, she was president of Mutual even after her family came to tie her at home.

As an amateur actress, she was the best; a fluent reader and memorizer—gifts she passed on to her posterity. Although she was thus gifted, she still disliked to speak in public unless it was memorized, and even then she trembled from fright. The gifts and talents with which she was blest, she preferred to use on her home for her family. The nice singing voice of hers was used most of the time to sing lullabies to the little ones she loved so dearly and there were many on which to practice.

As a girl she thought how she would like to be a public worker, but even though the desire for this did not leave her, she made the best of the life she lived and no one knew of those secret ambitions.

She managed her home and kitchen especially well. Everyone loved to go there. She could feed a multitude. She wasn’t a fancy cook, but exceptionally good with plain foods. She could cook hot cakes for a dozen and by the time you finished eating, she had all the dishes done and the kitchen in order. Her mincemeat pies were the best. Also she was a very neat seamstress; much was done by hand. Her quilting was beautiful. She would get up early in the mornings and put a quilt on before the others were out of bed; she was always anxious to make things, but they had to be done just so.

On July 12, 1893, in Los Angeles, California, she married Joseph Thomas Goodman. He came to Arizona, a pioneer like herself, in 1882 from Utah where he was born November 29, 1869.

Annie Maria McRae (top right) with friends Roxsana Reed (dark dress) and Florence Curtis, c. 1889. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Annie Maria McRae (top right) with friends Roxsana Reed (dark dress) and Florence Curtis, c. 1889. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

He, with his parents and brothers and sisters, came to St. David in hopes that their dear father, whom they loved so dearly, would regain his health which was failing rapidly in Minersville, Utah. But he only lived a few short years, and left his wife and nine children with no means of support.[37] But these children knew how to work and save, and they took their great responsibility as they did everything else, in their stride, and went to work.

Joseph, or Joe as he was always called, was the second son in his family, a lad of sixteen when his father passed away. He had a great desire to get a good education, but, due to circumstances of which he had no part, his desire was not fulfilled. However, with the gifts with which he came to earth, no one outside of close relatives and friends knew it.

Having an invalid father may have been a blessing in disguise, for they all knew how to assume responsibility and weren’t afraid to ask for a job. He always said: “Honest work hurts no one, so be proud to work.” His first job was with a friend of the family who agreed to board him and give him sixty acres of land if he would work for two years.[38] This looked good, but he got his younger brother George to go too, so they only had to work a year. Then when the final settlement came, the man had no title to the land, had just been claiming it, so it was not his to sell. The result was that the oldest brother, William, was twenty-one and could use his filing rights. This he did, and the 160 acres was divided among the four oldest boys, each got forty acres of his own, and did they all feel wealthy. Perhaps someone else would have complained, but not Joe. He put that down as experience for he had learned much in that year and to complain was beneath him.[39]

This forty acres, which he earned the hard way, and a team, wagon, cow, and a few chickens that were earned in the same manner were his sole possessions when these two married. But they had courage and a desire to get ahead, and best of all, they had each other!

Much could be told of the hardships they endured, the lack of necessities to say nothing of what they desired, the worry and hard work that went on from day to day. Yet much can also be told of their joy and their laughter, and the jokes they played on each other. They didn’t dwell on the sordid side of life. They had their ups and downs, and if there were more downs than ups, they accepted that too.

The little two-room house they built was lined with newspapers, no screens on doors or windows, and hand-woven rag rugs on the rough board floor. Straw or corn husks filled the coarse mattress on the homemade bed. A couple of plates, knives and forks and spoons were the number of eating utensils they owned. Two wooden boxes with curtains in front made a very good cupboard. The crude chairs and table were made from whatever material they could find. This was the furniture they had in their little house. Yet no mansion with its glitter of lights and cut glass and sterling silver, rich mahogany furniture and velvety carpets covering the floors ever had any more loving or understanding people dwelling inside than did this little two-room cottage in the sweltering Arizona summers and the bleak, windy, snowy winters.[40]

The year following the marriage of these two people, a family began to arrive. It may seem strange to those of today, who have such enormous doctor and hospital bills, to say nothing of food and care for children, how anyone with such a limited income could afford to have one baby, but these two people were the parents of thirteen—ten boys and three girls.

The first was a girl, sort of restless and maybe with too much ambition to explore. The neighbors still marvel that the parents survived. They called her Ruth. She was the mother of ten children and after her husband died, filled a stake mission.

The next four were boys—very obedient, and causing their parents little trouble. Alma Donald, the first one, was born on the second wedding anniversary of his parents. He was not too strong as a child but grew up to be as well as any of the others. He served in World War I, filled a mission to the Southern states, and farmed at St. David.

Joseph Edwin then came along. He was always very ambitious; served in World War I, filled a mission to the Southern states, served as postmaster of St. David for a number of years, as stake Sunday School superintendent, and as stake mission president.

Howard Arthur was next. He never stopped doing hard work until he became older and his back gave out on him. He was good natured and imposed on by all. He was a bishop and also counselor to the stake president.

Alexander was the fourth, a witty, cute little fellow who never lost that wit as long as life was in his body. He was afflicted with heart trouble most of his later life, but no one ever heard him complain. He was always one of the first to visit the sick. He attended barber school and practiced ’till health gave out, then was in the real estate business until his death July 5, 1952.

About the time Alex was a year old, Joe got a “call” to go on a mission for the Church. It never entered his mind to refuse, so in the fall of 1901, he left his loved ones in the care of the brothers of his wife and set out to fill a mission. These two brothers of his wife were Parley and Milton [McRae]. He was sent to Colorado in the winter time and perhaps the Arizona sunshine had been such a habit that the bleak, cold snow in Colorado was more than he could stand. He took rheumatic fever and had to be sent home on a stretcher. The nice healing sunshine worked wonders, and in less than a year he could work again. His disappointment at not fulfilling this mission was keen, and he vowed he would send all of his family on missions. This he did, but Ruth, who later filled a stake mission, and Harry filled a mission after his father’s death.

Alice, a frail little girl, came next. She was only permitted to stay sixteen short years on earth, but her sweet spirit remained.

Then Morten—a mischievous little boy who liked to run away from home as soon as he could walk, and spent most of his first two years tied to a porch-rail. He got loose long enough to get kicked in the head by a mule; the scar still remains. He did a lot of work on road jobs. He filled a mission to Germany; and while bishop of the Papago Ward, sent his first full-time Indian missionary out.[41]

A little premature boy was next; he only lived two hours, not named.

Then Glen—a serious little fellow. He was always a clean, good boy—the first of the family to become a bishop. He filled a Mexican mission and was postmaster of St. David; the St. David Chapel was built while he was bishop. He had lots of fun even though he was serious.

Mabel was the third and last girl in the family. A span of eight years lapsed between the three girls. Petted and spoiled perhaps by her brothers, she was good-natured, always ready to give a helping hand. She always held positions in the Church and filled a mission to the Southern states. Her husband was bishop for a number of years in Mesa.

Frank, a much too practical child, was next. He didn’t believe in Santa Claus even when a small lad. He was very thoughtful but just lived to be twelve.

Harry was the one who made an even dozen. His grandmother Goodman said before he was born that he would be the joy of his mother’s life, and in a way he was because Frank, before him, had died and the last one, Orson, only lived two weeks; so Harry got all the love that these two would have received. He was the first of the family to graduate from college and filled a mission to the North Central states. His mother did the janitor work at the church-house to help keep him out.

Thirteen children came to this home. The little two-room cottage was gradually replaced with a bigger and better home. The horse and wagon soon became outdated and a car was used to take the family around.

With such responsibility you might wonder how they went anywhere, but Sunday School and church meetings were attended by all. The father was Sunday School superintendent for years and president of the YMMIA.[42] They went on trips quite often, which proved to be educational as well as entertaining. It was in 1905 that this couple went to Salt Lake City to be married in the temple. They were sealed to each other some years previous by Apostles in the Church who had been sent to Arizona to perform this work.

They raised to manhood and womanhood ten of their thirteen children. Eight filled regular missions for the Church in the United States and in foreign countries, spending from two to three years each. At one time, two of the boys were in the mission field at the same time. Joe often said he received blessings unmeasured when he had a child on a mission, and at the time there were two, the blessings were doubled. All of their children have married in the temple, and have all been active in the Church. They have been law-abiding citizens always. Their fellowmen have been treated fairly by them. The teachings of such wonderful parents will always remain with them.

After completing a full mission on earth, Joe was called “Home,” June 7, 1935. Annie was permitted to remain thirteen years longer. She spent this time in the service of her friends and loved ones, attending sessions at the temple for those of her departed ones, which was a joy to her. She made many trips to the homes of her children in other cities, as well as visiting with her sister Mamie. At one time, these two sisters journeyed to Carthage to see their brother Alexander and his wife who were caretakers of Church property there.[43]

Her many friends of her community rejoiced at Annie’s return after she had been away for a few days as she was such a comfort and joy to all who knew her. She spent long hours clerking in the store as well as helping in the post office with never an idle moment. “Better to wear out than to rust out,” she would say. She never failed to have a book handy that she might read when an opportunity availed itself. She was ever eager to learn.

She was seriously ill for two months before her passing on April 21, 1948. She was buried in St. David, Arizona, alongside her husband and three children.

Ellis and Boone:

At the death of Joe Goodman’s father, his mother, Margaret, was left with nine children to support. As later family members wrote, “She took the family’s only cow to pay the funeral expenses. Then with five dollars, she bought a few bars of soap and other small articles and sold them in one of her rooms. This venture finally grew into a small store.”[44] The store eventually included the post office and later telephone office. It became the St. David Store, which Margaret Goodman, and other family members after her death, operated until the 1940s. Annie Goodman apparently helped at the store when she was also a widow.

When Annie’s oldest daughter, Ruth Goodman Tilton, wrote this sketch, she also included the Edgar A. Guest poem, “Mother’s Way.” The first two lines are: “Tender, gentle, brave and true, / Loving us whate’er we do.” One sentence that Clayton left out of the PWA sketch echoed the same sentiment. Tilton wrote, “Are not children blessed by coming to such parents as these?”[45]

Elizabeth Amy Barton Greenhaw

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[46]

Maiden Name: Elizabeth Amy Barton

Birth: December 1849;[47] Williamson Co., Texas

Parents: John Barton and Melissa Amy Ray

Marriage: Hosea George Greenhaw; July 10, 1878

Children: Hosea (1879), Joseph B.? (1880),[48] Miriam (1881),[49] Paul (1884), Harmon? (1887), May? (1889), Mary (1890), Leslie (1893)

Death: August 31, 1926; San Diego, San Diego Co., California

Burial: Greenwood Cemetery, Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

From Williamson County, Texas, to Phoenix, Arizona is not very far as the crow flies and could easily be made in a couple of days in an automobile or in that many hours by plane. These are the modes of travel nowadays, but back in 1850, these things were not even dreamed of. It was in that year when John Barton and his wife, Amy Ray, decided to find a new home in the Golden West. Their journey was made by water, through the Isthmus of Panama to San Francisco, California.

John Barton was born in Indiana. He met and married Miss Amy Ray in Texas, and there little Elizabeth Amy was born in 1849. Things were plenty exciting in those days in the western state of California, and Mr. Barton stayed there until 1875.

Poor Mrs. Barton did not long remain with her family, but passed away leaving a grief stricken husband and four children, two boys and two girls. Elizabeth was the eldest and early learned to assume responsibility and care for her little two-year-old sister and the other members of the family. In spite of the home duties, Elizabeth attended school and graduated from the Washington College near San Francisco in 1874.

She had no trouble getting a school, teaching in Ventura in the Santa Paula District. She kept her little sister, Rena with her all the time, and became her first schoolteacher. Elizabeth was a favorite with her pupils and the patrons of the school and before the term closed in May, she had signed up for another year.

School was barely over when one day a fine new Bain wagon drawn by four high-stepping horses stopped at the boarding house where Elizabeth and her sister were staying. In it was her father and the two boys, Arizona bound; it was like a thunder bolt from a clear sky.

Elizabeth did not want to go. Her plans were made for another year and her promise given. All of her friends were here; why had her father taken such a notion in his head? Arizona of which she had never heard anything enticing. Land of deserts, cacti and noted outlaws and hostile Indians. Truly her early training of obedience to parents and the need her father and the boys had of her were the only things that brought her. “What about her school?” asked the trustees. Oh, she would be back next fall to teach it.

They started from Anaheim, California, on June 24, 1875. Mr. Barton had 2500 head of sheep to bring along; those with five burros, two sheep dogs, a puppy, and the four children completed the company.

It took all hands to drive the sheep. As they had to graze en route, Mr. Barton sought out unfrequented trails where the grass and forage were better. He was one of those hardy pioneers who had spent most of his life in the open. He was a woodsman on the order of Daniel Boone. He could have been a scout of the highest order for his experience in woodcraft, habits of animals, and being able to get a living from Mother Nature were highly developed. There were no Indian encounters, but cattlemen made their trip unpleasant whenever their route led across the ranges claimed by them.

One ideal camp was made up among the hills on public domain, and here the family with their sheep remained some time. One day Mr. Barton saw some bees gathered around the water hole. Now he was a natural bee-man. He knew there must be some hollow trees not far away where they stored their honey. He fixed up some sugar and water into a syrup and put the plate containing it where they would find it—then with a handful of flour, he waited. Soon the bees found the syrup and he managed to sprinkle them with the flour then watch which way they went. It was not long before he located three or four trees filled with honey.

There was the honey all right but what could he store it in? Deer were plentiful, so he killed one, took the skin off whole by cutting it around the neck and just above the hoofs of the four feet. The skin stretches very readily when it is wet so he peeled it off, washed and dried it thoroughly, then made a bag of it by tying the leg openings with buckskin and using the neck through which to pour the honey. It served as an excellent storage receptacle, the honey keeping fresh and pure therein as long as it lasted.

The venison was cut in strips and dried as “jerky” and was very choice eating. After the buckskin had served its purpose as a bag, it was cut up and used as moccasins for the boys and Mr. Barton to wear.

Whenever the travelers came to a good place where there was water, they would remain for some time for the sheep to fill up and rest. Crossing the deserts they suffered greatly for the want of feed and water—then feed had to be purchased and packed on the burro. There was a great loss anyway, and the family reached Phoenix, April 3, 1876, after almost a year on the way. The few people who were here were very kind and hospitable, and the Bartons’ four young people were quite an addition to the society of the place.

Elizabeth found that there were already two aspirants for the school, so decided to return to California and teach there. An amusing incident is told of how the schoolteacher in Phoenix was selected. All were great friends and wanted to remain so, so they went to Governor Safford at Tucson for a decision.[50] One of the ladies was a widow. Solomon could not have decided more briefly nor wisely. He said, “Give the school to the widow this year. She will get married. Next year give it to the old maid.”

Elizabeth obtained a position in the college she graduated from and decided to take her sister back with her to finish her school. Now the problem arose as to how to get to California. A newcomer Mr. Linville was going to bring back a load of fruit trees and the young ladies might go with him. His wagon and trailer were loaded with barley to feed his four mules; sacks of it were left at different places along the way so he would have it to feed on the return trip.

The journey was begun in November 1876 and was a very pleasant one. The girls were happy to be returning to their friends. However, Elizabeth had left her heart in Arizona with a young musician, Hosea Greenhaw. He soon followed her to California, and they were married.

The wedding was a fitting one, and the couple began their journey through life by returning to Phoenix. The Southern Pacific Railroad ran as far as Yuma so they came that far by train and the remainder of the way in a light wagon. Their furniture was freighted from Yuma.[51]

It wasn’t so hard for Elizabeth to come to Arizona now, and she was determined to be a true wife and helpmeet no matter where her lot was cast. Her home, though humble at first, was one of refinement and hospitality. Her husband was a fine musician, was endowed with a marvelously rich voice, and besides was a good provider. Young and old alike gathered at Elizabeth’s home where they knew there would be a warm welcome and entertainment. Eight children came to bless this happy union, five of whom grew to maturity.[52]

Mr. Greenhaw became an extensive land owner through purchase and homestead, and Elizabeth had several homes. He was fond of good horses and always had plenty of saddle horses for his family and his neighbor’s young people who were not so well supplied.

The Greenhaws have the distinction of owning the second, if not the very first piano in Phoenix. It had been shipped around by Cape Horn to San Francisco, then on the train to Yuma and from there in a freight wagon. Elizabeth never had to sing her babies to sleep—her husband did that or lulled them with the soothing tones of his violin.

Good fortune and caution prevented accident in her little brood with the exception of a broken arm suffered when a horse fell on one of the boys. In the possession of Dr. Gunn’s Doctor Book, Elizabeth had a priceless treasure, in those days when doctors were so scarce.[53] It contained all the symptoms of every disease and the simple home remedies and treatments of them. Those books were very scarce, so when anyone was ailing she was sought out, and from her large store of medicinal herbs, roots, and barks she would select the ones prescribed by Dr. Gunn, and with her cheery, helpful manner go into the homes of the afflicted and bring healing and comfort.

Mr. Greenhaw tired of the hot, dry summers in the Salt River Valley, so he took his family to the state of Washington. They did not like it there so after only seven months absence, they returned to their home in Arizona.

Later they bought a home in San Diego, California, but portions of each year were spent in their home in Phoenix. Here in 1911 her husband passed away. Although part of her very life seemed gone, Elizabeth was not a person to parade her grief. Too much of her life had been spent in service to others to permit her to spend much time thinking of her loss, so until death came to her in San Diego in 1926 she was busy bringing sunshine into the hearts of all who knew her. With her passing went a true pioneer of both California and Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

When Mormon pioneers began attending the Heard Reunions in Phoenix, they were often honored as having lived in Arizona the longest because Mormons had been living and ranching in the Arizona Strip many years before Brigham Young directed that settlements be established along the Little Colorado River or at Mesa.[54] James Pearce was so honored at the first Heard reunion in 1921, as was William J. Flake in 1931. Roberta wrote that at the reunion, “Father had the distinction of being the first person there to touch Arizona soil, having come here first in 1851 [meaning traveling from Utah to San Bernardino, California], then pioneering in 1877, [and] exploring in 1873. He wasn’t the oldest man as there was one 104 years old. They called upon [Father] to speak, and I heard several say that his [speech] was the best one, and that he didn’t need any microphone. Every honor was shown him, and I was so proud of him.”[55]

Nevertheless, the pioneering experiences of the Bugbee, Greenhaw, Murray, and Osborn families are different from the Mormon pioneers. In particular, each of these families had close ties to California—either living in California for some periods of time or sending their children there for education. As noted here, John Barton came to California early, traveling by ship instead of using an overland trail. So, Elizabeth Barton grew up in California and when she came to Arizona, it was from California and not from the East.

Catherien Ellen Camp Greer

Roberta Flake Clayton/

Maiden Name: Catherine Ellen Camp

Birth: October 17, 1837; Dresden, Weakley Co., Tennessee

Parents: Williams Washington Camp and Diannah Greer

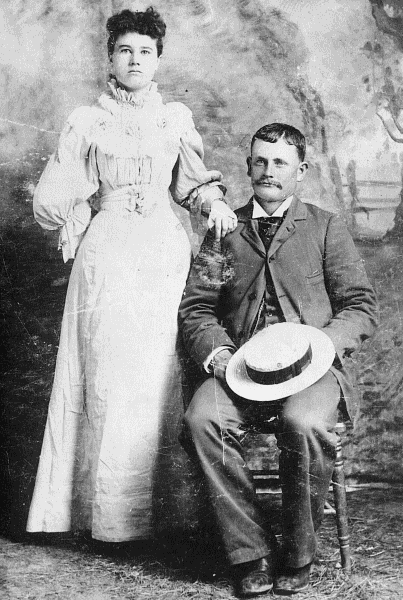

Marriage: Thomas Lacy Greer; November 25, 1855

Children: Nathaniel William (1856), Thomas Riley (1858), Gilbert Dunlap (1860), Deseret Diannah (1861), Richard Decatur (1864), John Harris (1866), Oasis Ann (1867), James William (1870), Lacy (1872), Harriet May (1875), Ann Terry (1877), girl (1878), Margaret Ellen (1879)

Death: November 15, 1929; Holbrook, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

One of the most widely known of Arizona’s Pioneer Women was “Aunt Ellen Greer,” beloved by all who knew her.

On October 17, 1837, over one hundred years ago, she was born in Dresden, Weakley Co., Tennessee. Her parents were Williams Washington and Diannah Greer Camp, and she was the tenth child of the family. The Camps owned a large plantation and slaves to do all the required labor, so Ellen’s girlhood was spent in a home of plenty, and she was allowed to enjoy to the fullest those carefree days.

Ellen’s father was a member of the Campbellite faith, and her mother a Baptist until they heard some missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Then the father joined that church, and disposed of his plantation and part of the servants [slaves], and prepared to go to Illinois where the Saints were then located. Mrs. Camp did not become a member until after they reached Nauvoo.

In 1850, the family crossed the plains and immigrated to Utah.[56] During this journey a very tragic incident happened that cost the life of one of the Camp girls and almost that of another. Ellen and her sister Emma were walking helping the Negro girl, Charlotte, drive some cows when they discovered the dead body of the doctor they had had in Missouri. He had died of cholera and been placed in a shallow grave, from which wolves, possibly, had dragged him. The girls hastily pushed the corpse back into the grave and threw some rocks on it as a sort of protection. They had scarcely completed this when Ellen became unconscious, and then Emma contracted the dread disease, from which she never recovered and had to be left in a wayside grave. This was a great shock to Ellen, and a lasting sorrow, so close had the girls always been together. The casket was made of lumber that had been one of the wagon boxes. Years later the father took a white marble marker to place on the grave of his daughter.

Many things of a beneficial nature were taught the Camp children by Charlotte, their colored servant, such as honesty, cleanliness and neatness. She was greatly missed when she died two years after the family reached Utah.[57]

Ellen’s schooling began in Nauvoo, and her first teacher was a Mrs. Fiddler. This only lasted a short time as the move westward began. In Salt Lake she had several instructors, among them sewing and dancing teachers. She proved a very apt pupil, was a graceful dancer, and as for her sewing lessons, they proved very beneficial when she had a family of her own to sew for. She early learned also to spin, weave and knit, and all her life was fond of piecing quilts, and later, when facilities for doing fancy work were easier, spent much time in embroidering. She entered her handiwork in fairs in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas and won many prizes.

Shortly after reaching Salt Lake City, her father established a general merchandise store and was instrumental in assisting in the development of that part of the country.

When Thomas Lacy Greer saw beautiful, accomplished Ellen Camp, it was love at first sight with him, and he declared that she was to be his wife; accordingly he made a call at the family home that same evening. He was a distant relative of the mother and was welcomed and presented to the family. The courtship progressed with surprising rapidity, since one of the interested parties had already made up his mind. With Ellen it was different. She was quite a belle and had many beaux to choose from, but finally the Southerner won, and they were married just after Ellen had passed her eighteenth birthday, on November 25, 1855.

The first unexpected episode in their lives was in June 1856 when her husband was called on a mission for their church to go to Hill County, Texas. They put their belongings in one wagon, and with a yoke of oxen to pull it, and the two elderly slaves that had been given Ellen by her parents to drive them and look after the work, they started out. Ellen preferred to ride her favorite pony, and took great joy in the trip.

Their missionary labors were successful, and they made many friends and converts, Ellen doing her part by demonstrating in her life and the teaching she gave her children the example of the Lowly Nazarene.

Politically the country was in a state of unrest. Texas had thrown off the yoke of Mexico. The slavery question was being agitated, and the Greers were in Texas all during the Civil War. Now for the first time, Ellen was faced with the necessity of economizing. The price of the staple provisions was so high and these articles were so scarce that she found herself helping to grind the grain on a handmill and having to put the children to bed while she washed their clothes.

Her beautiful clothes were cut up to make dresses for her little girls. She was the mother of twelve children, ten of whom were born in Texas. Her husband had been a soldier in the war with Mexico and had received wounds from which he suffered as long as he lived. He was successful in getting a large herd of cattle and as soon as the sons were old enough to sit in a saddle they were put with the cowboys to ride after the cattle. It was while riding with the herd that her second son, Riley, was thrown from his horse and was injured inside. This was on June 22, 1873. He suffered intense pain for a month and twelve days before death came to relieve him. Who can tell what the loving mother suffered during those terrible days?

In 1876 the Greer family left Texas for Arizona.[58] With their cattle and horses they came up through Indian Territory, into Arkansas, then spent the winter near Wichita, Kansas. Here the boys of the family had many exciting experiences with thieves who tried to drive off some of their cattle. When the grass got started sufficiently in the spring, they again started out on the trail, passing through Colorado and New Mexico, finally reaching the Little Colorado River where they established a ranch at a place now called Greer’s Ranch in Apache County. Here again the Greer boys had no end of trouble, this time with Mexican sheep herders as well as cattle rustlers. These boys inherited from both father and mother a rare degree of courage, and lawbreakers soon learned to give them a wide berth. They had one faithful old black man. . . .[59] All that was black about him was his skin, and those who knew him soon forgot that. He was the first one of his kind in this part of the country, and the Mexicans thought he was “charmed” and let him have his own way.

On July 30, 1881, at the age of fifty-five years, her husband passed away. The Greer home had a reputation far and near for its true Southern hospitality and this still continued. Any and everyone who came that way were welcome guests. There was a houseful of boys and girls, and a brave, cheerful mother there to receive and entertain. For forty-six years after her husband’s death, she continued to face life courageously, hopefully and resourcefully. Her trials were never so much those of poverty, as confronted other pioneers, except during the war when she was in Texas, but in her early days in Illinois there was the constant dread of the mobs, then the Indians on the Plains, the Mexicans in Texas, and the Mexicans and the outlaws in Arizona.

She was a strict adherent to the tenets of her faith, and family prayer was strictly observed whether she and her family were alone or company was present, and many a cowboy who had not knelt in prayer since childhood days at his own mother’s knee, joined “Aunt Ellen” and her little ones in their devotions.

Thomas Lacy and Catherine Ellen Camp Greer. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

Thomas Lacy and Catherine Ellen Camp Greer. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

Although while the children were small they lived on the ranch, their education was not neglected. Governesses were employed, and all were given the advantages of an education in music. Their mother’s sister, Margaret Baird, was the capable instructor. When they were older she took them to Provo, Utah, where the youngest four attended several terms under the best teachers. She spent two winters at Tempe while her daughters attended the Tempe Normal.

Death, in tragic form, seemed to walk beside her. Aside from the death of her son Riley, as already noted, her daughter Deseret died from injuries received when thrown from a buggy by a runaway team. This was July 28, 1898. She left four boys. Thanksgiving Day 1904, her youngest son, Lacy, was killed at the stock yards in Holbrook by an 800 pound gate falling on him, leaving a wife and seven children. In May 1911, her son-in-law Wallace Riggs was accidently shot when the loaded gun he had across his lap was thrown against the dashboard of the wagon by the team he was driving. Her son Gilbert had died January 22, 1895, leaving six children. On November 1, 1907, her daughter May passed away and her not knowing of her illness until she was buried. These deaths together with that of her daughter-in-law Hannah Kempe Greer were some of the things which proved the pure gold of which she was made. In every case she did all she could for the bereaved.

“Aunt Ellen” was always actively engaged in social and religious duties. Even when she lived on the Ranch, she was president of the Relief Society at Erastus (Concho) and would drive the nine miles twice each week there and back to attend to her duties. Finally, she moved to St. Johns where it was easier for her to do those things. The latter years of her life were spent in Holbrook where her sons Nat and Richard, and her daughter Anne, resided.

Up until six months of her death, she took an active interest in everything about her. At that time, she fell and hurt herself very seriously and a stroke was the result. She grew old gracefully and beautifully, and retained her youthful spirit to the age of ninety-two years and one month. Fortunate, indeed, were those who knew her and were counted among her friends, for from that friendship they learned the true significance of the word.

She fell and hurt herself, after her ninety-first year; this brought on a stroke about six months before her death. She lived to the ripe old age of ninety-two and was to the last day of her life a comfort and blessing to all who knew her. She passed on to that great immortal world November 15, 1929, and wore in death as in life a peaceful, pleasant, and comforting countenance.

The above is the story as given to the author by Ellen Camp Greer. We [meaning RFC and her typist] are including reminiscences of her childhood as she wrote them herself, and also, some faith-promoting incidents which she wrote in the extensive history of her life.

Anecdotes and Reminiscences of Her Life as Related by Ellen C. Greer[60]

I can remember when I was only five years old, when my father joined the Church. I recollect being taken to school. We had what we called the “Female Academy” at Dresden, Tennessee, where I was born. I had two brothers that were going to school in the country and they took me. I was the oldest girl living of my mother’s children. I talked in school. Of course, I did not know there was any rules, and me and another little girl were sitting on a little platform, and the teacher called us up and gave us a lick or two with a ruler. My father was one of the trustees. He hit us a lick and then made us stand up until we would recite a rhyme. Well, I made up a rhyme alright: “The Lord is a mighty whacker, He used the Devil for his cracker.” The teacher was nearly turned out of school for that. The teacher’s name was Juson [sic] Camp.

My mother had fifteen children, and I was the tenth one. I did not go to school any more until I went to Nauvoo. But just before my father went to Nauvoo, he was fixing his wagon, that was after he joined the Church and everybody went against him. He was a blacksmith by trade and had a black man to help him. He was setting a little board in shape, and there came a mob of fifteen men, and I saw the men and they came to give my father some tar and feathers. They were all painted, and Father was hammering, and the old black man was frightened, and Father threw a hammer across the floor and knocked down at least two of the men, and then he gathered up irons in every direction and went after them, and the black man and I went behind the bellows and hid. When my father came back, he asked Ike who was the [black] man, “Ike, you black rascal, why didn’t you help fight those men?” and Ike didn’t look up but said, “Well, Massa Williams, I thought you was enough for them few men.” My father laughed but said no more to him. “Yes sir, he just gathered up those irons and fought his way through,” as Brother Brigham always told Father. Father said he did not want a religion if he could not fight for it. If it wasn’t worth fighting for, he did not want it.

As soon as they got the wagons fixed, we went down to Nauvoo to spend the summer. We spent two summers there. The first school I went to in Nauvoo was to an old lady by the name of Fiddler, she was a Mormon woman and taught the little children; she was a widow lady and had a family. There was a clay pile that potters use for making stoneware or earthenware and it was right in the center of town and they used so much of that clay, and me and a neighbor girl used to slip out and make vessels out of this clay. We had pots and everything that we could cook with. We made cats and dogs after a fashion.