F

Lester Burt Farnsworth, Roberta Flake Clayton, and Ida Flake Willis, "F," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 171-202.

Christianna Dorothy Bertelsen Farnsworth & Mary Ann Staker Farnsworth

Lester Burt Farnsworth[1]

Christianna Dorothy Bertelsen Farnsworth

Birth: January 9, 1852; Skraepperhuus, Hojslev, Viborg, Denmark

Parents: Niels Pedersen Bertelsen and Maren Larsen

Marriage: Alonzo Lafayette Farnsworth; March 9, 1874

Children: Raymond Alonzo (1876), Lester Burt (1879), Mary Ann (1881), Richard Kent (1883), Elmer David (1885), Franklin Lehi (1888), Annie Roine (1890), Alonzo Lafayette (1897)

Death: October 25, 1922; Colonia García, Chihuahua, Mexico

Burial: Colonia García, Chihuahua, Mexico

Mary Ann Staker Farnsworth

Birth: January 21, 1848; Pigeon Grove, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa

Parents: Nathan Staker and Jane Richmond

Marriage: Alonzo Lafayette Farnsworth; December 1, 1864

Children: none

Death: January 7, 1929; Colonia García, Chihuahua, Mexico

Burial: Colonia García, Chihuahua, Mexico

As I Remember My Two Mothers

Folks say I am growing old, because I have seen eighty-two birthdays, but I remember my mothers as if it were but a few years ago. The first I remember noticing that I was different was when I was about four years old. In what seemed to be my own home I had a mother whom I adored, but there were no brothers or sisters in my home. Just next door there lived a family and I was always taught to call the lady who lived there, Mother, and the boys and girls were brothers and sisters. Just why my brothers and sisters called my one mother Aunt Mamie was not very clear. When I was about six years old, I was told the very beautiful story of love and sacrifice that had been made by my first mother, and it is of her I wish to write at this time.

Christianna Dorothea Bertelsen Farnsworth. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Christianna Dorothea Bertelsen Farnsworth. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Christianna Dorothy Bertelsen was born January 9, 1852, in Denmark. She was the tenth and last child of Niels and Mary Bertelsen.[2] The family joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and like most of the early converts, they had a great desire to come to Zion and began making preparation to come to this choice land. It wasn’t long until Grandfather had enough money to bring Grandmother, himself, and little Anna as she was called by her family. So the other nine children were arranged for and would be sent for as soon as a home was established among the Saints. The other children all came over except the oldest daughter. She married in Denmark and chose to stay there.

Little Anna could come for half fare because she was only eleven years, and laughingly Grandfather said, “We will let little Anna sing her way across the ocean.” And this serious minded little girl did just that. Anna had a beautiful voice, and because of her willingness to sing and serve, she was constantly in demand, and the captain in return kept her and her parents in food. They were eight weeks crossing the Atlantic Ocean. The Lord was mindful of them and soon they were on their way to Utah. Anna had many admirers, but I have always believed she had a special sacrifice to make and was reserved for that time.[3]

Mary Ann Staker Farnsworth. Photos courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Mary Ann Staker Farnsworth. Photos courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

At the age of twenty-two, she married Alonzo Lafayette Farnsworth as his second wife. Anna and Mary Ann Staker, Father’s first wife, were very dear friends. Mary Ann, who was later known to my brothers and sisters as Aunt Mamie, was a very frail lady. She and Father had been married a number of years but had never been blessed with a child. So like Sarah of old, Mary gave Anna to Father as a wife.[4] In about two years, Anna had a son, and knowing her as I do, I believe it was always in her heart to share her family with Mary, but Raymond was a very fragile and delicate child and took a lot of care. So Anna said to Mary, “When my second son is born he will be yours,” and that is one of Mother’s virtues. What she said, she lived by. I was the second son, just two years younger than Raymond, and when she looked at me she said, “This is Mary’s boy. He is the image of his father.” Because doctors were few and far between there were no formulas, so mothers breast fed their young. So it was agreed I should stay with Mother until I was six months old, then she dressed me in my best, and carried me to Mary’s loving arms and, with pangs in her heart only a mother could know, she said, “Here is your son Mary, to love and raise as you wish and teach him to call you mother.”

There were no demonstrations or pleas for mercy or sympathy. She had made her sacrifice and only God understood and could ease the pain. I have been asked many times which mother I loved best, but I honestly could not say. Mother bore eight children; the last one only lived a few days. Seven of us grew to adulthood. Mother was always gracious and kind to all who knew her; she was a natural nurse. Always a member of the choir, she was called on to sing in church socials. She was an excellent seamstress, and her cooking was a special gift. I can almost see the beautiful hats she would fashion for the town ladies. In later years, the family would gather around the organ and sing the old familiar songs. In fact, most of my family were talented in voice and music.

After I married, my Mary mother always lived with us and about a year before Mother Anna passed away, she and Father sold their home and came to see us. How we appreciated and enjoyed having my two mothers and father with us. In October of 1922, my Anna Mother was taken home to the beautiful mansion which our Father in Heaven prepares for the faithful. A little later Mary Mother and then Father followed.[5] Now the three lie side by side in the little cemetery in Colonia García.

Ellis and Boone:

This act of one wife giving another wife a baby to raise as her own was not uncommon during polygamy. The Farnsworths were living in Colonia García at the same time as Edward Milo and Charlotte Maxwell Webb, and this may be the story that their daughter, Estelle Webb Thomas, told in her book Uncertain Sanctuary, although she changed the names, and a few minor details are different.[6] Variations of this same sacrifice are also found in the sketches for Happylona Sanford Hunt, 296 and Anna Benz Kleinman, 372.

In this sketch, Lester Farnsworth does not mention that Alonzo L. Farnsworth married a third woman as a plural wife. Alonzo and Ida Henrietta Tietjen were married April 8, 1875. Ida Henrietta Tietjen was born April 8, 1853, a daughter of Johann August Heinrich Tietjen and Ida (Eda) Dorothea Friedrika Krueger in Hingelstad, Saken, Sweden. Alonzo and Ida had ten children. Ida Farnsworth died May 1, 1906, in Santaquin, Utah, and is buried there.[7]

Juanita Gonzales Fellows

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview

Maiden Name: Juanita Gonzales

Birth: October 18, 1865; San Miguel, Sonora, Mexico

Parents: Jacob Gonzales and Eulalia

Marriage: William Wallace Fellows;[8] August 17, 1882

Children: Stella (1884), Alice B. (1885), William Jacob (1887), Benjamin Harrison (1889), George Washington (1890), Marinda Irene (Erinia) (1894), other children unknown[9]

Death: December 28, 1951; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Double Butte Cemetery, Tempe, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Three weeks is rather an early age to begin pioneering, but that is as old as little Juanita was when her parents Jacob and Eulalia Gonzales moved from San Miguel to Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico. The tiny daughter and only child of this couple was born October 18, 1865. Her father was part owner of a ranch and large herd of cattle. He bade his young wife goodbye one morning to go and look after his cattle interest. The next day word was brought to her that he had been murdered by renegade Apaches.

As was true in Northern Arizona, the bloodthirsty Apaches were also a constant menace to the people in Chihuahua and Sonora. To the Mexicans, the crow is almost a sacred bird, because crows would fly overhead and give warning before these Apache raids. That would give the people a chance to hide their valuables and secret themselves and their animals in the numerous caves with which those sierras are honeycombed.[10] To kill a crow brings a twenty-five dollar fine in those two states.

Juanita’s grandfather went and brought home the lifeless body and buried it. The young wife was inconsolable, and for a year lingered between life and death. Little Juanita was given all the love of her poor mother’s heart, as she so resembled her father.

Conditions in Mexico at that time were in such turmoil that life and property were unsafe. Young Jacob’s partners robbed the widow of all that the Apaches left. The government was unstable. Law and order was unknown. After being robbed many times and being unable to obtain redress and having four of his sons conscripted into the army, Grandfather Gonzales disposed of his large land holdings in Sonora and came to Arizona.[11] He brought his family including his widowed daughter. Juanita was nine years old at that time. They located in Tempe, where Mr. Charles Hayden already had a large store and mills.[12]

Eulalia Gonzales was beautiful, with her olive skin, large dark eyes, and luxurious black hair. Her sorrow added a wistful pensiveness to her that enhanced her beauty. Many suitors came to woo her in her new home. Finally she married William Osborn.[13] She knew no English, but Mr. Osborn had previously been married to two Mexican girls and could speak Spanish fluently. By the first wife he had two children, but they and their mother died. By Eulalia he had one son; so now Juanita had someone to care for and play with.[14] As a stepfather, William Osborn was all that could be desired, always kind and generous to Juanita.[15]

Juanita’s grandfather had brought fruit trees from his orchards in Sonora and set out two large orchards here in the Valley. Most of the trees he brought grew and bore prolifically in this climate.

Mr. Osborn had about twenty acres of sugar cane each year and made molasses and even boiled it down to a sugar—piloncillo as it was called by the Mexicans.[16] He used to make preserves of peaches which were plentiful here in the early days and of a delicious quality. He also made sweet potato preserves in his large molasses vats.

Juanita went to the American schools, but she also had a Spanish instructor to teach her the language and legends of her people. When Juanita was seventeen, she married William Wallace Fellows.[17] “I suppose by his name you can guess his nationality,” Juanita ventures. The Scotch part was apparent, but I [RFC] had to be told that the surname was English. Mr. Fellows was an engineer at the Vulture Mine, and the next day after the festivities were over, August 17, 1882, he took his bride to the mine with him where he had a home all built and furnished for her.[18]

The parting between Juanita and her mother was a very sad one. They had been so much to each other. Juanita seemed the only tie between Eulalia and her people—not only in looks but her very actions reminding her mother of her murdered father.

Mr. Fellows could not speak a word of Spanish when they were married. Juanita could speak English, so they courted in that language. Juanita says love needs no spoken language, that it will find a way. A cousin of Juanita’s had married an American and was living at the Vulture, so she was not so lonesome.[19]

The eldest child, a daughter, was born at the mine, and then they moved to Tempe where the other nine were born, five girls and five boys.[20] Two of each died when they were small, but the other six are still alive and are active in civic and social affairs.

Juanita says she is a firm believer in large families. She very greatly enjoys hers and, now that she is a widow, takes much pleasure in visiting in their homes. She had one son who went overseas, in the great World War conflict. He was gassed, but is gradually recovering from the horrors of it all. His home is in Washington, D.C., and his mother is looking forward to a visit there with him this coming summer.[21]

Like most of her people, Juanita is an ardent lover of flowers. Every thing she plants seems to grow and reward her care. She is also fond of pets.

Though she has been a widow twenty-six years and has had many chances to marry again, her love for her children and memories of her husband have prevented her. “He was a handsome man,” she says, “with his black eyes and curly hair. I have never seen another who looked so good to me.”[22]

When asked what she was going to do now that she has so much time, she answers, “Grow flowers, and learn to paint them.” Always she has loved art, but in pioneering days while raising her family she had no time to devote to it. She thinks one is never too old to do the things they want to, and I have no doubt but what she will prove it.

Among her possession are many choice books both in English and Spanish, and she is fond of reading. Vivacious, independent, hospitable and quaintly old-fashioned, Juanita Gonzales Fellows is a very charming person.

Juanita Fellows died December 28, 1951, in Phoenix.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch has a different feel from the majority of the other sketches in PWA, mainly because it is the only sketch documenting early Spanish settlers in Arizona. Juanita Fellows seems to have never had any connection to Mormonism. Juanita’s story also illustrates the wealth that early Spanish settlers brought to Arizona.

In southern Arizona, most Hispanic settlers came directly from Mexico (as did Juanita), but in northeastern Arizona most Hispanics were from the Rio Grande valley of New Mexico. Although Juanita was a resident of Maricopa County, it was Apache County where Mormons had extensive interactions with early Spanish-speaking residents (but there were Hispanics living in all the areas that Mormons settled). Many Mormon men (and some women, namely RFC, Ida Hunt Udall) spoke at least some Spanish, but the difference in cultures, including religious differences, kept the two groups distinct. It could be assumed that, at least as a child, Juanita was Catholic.[23]

Before 1900, there were a large number of Anglo men, many from Europe, who came to Arizona seeking their fortune. Many of them married Hispanic women; some examples include Frederick Augustus Ronstadt whose family eventually settled in Tucson, merchant H. H. Scorse of Holbrook (844), and Solomon Barth of St. Johns.[24] A slightly different intermarriage, but more important to Mormon settlers in Navajo County, was Corydon E. Cooley’s marriage to two of the daughters of Pedro, chief of a local Apache group.[25] Cooley was usually friendly to the Mormons and should be credited with the mostly peaceful relations between Apaches and Mormons.[26]

During the territorial period, Arizona residents were generally accepting of intermarriages, usually Hispanic women with European men. By 1900, this had changed as historian Thomas E. Sheridan illustrates: from 1872−79, 22 percent of the Pima County marriages were intermarriages as compared to only 9 percent from 1900−10. Sheridan also thought that most of the children from these marriages (in Tucson) adopted the Mexican culture.[27] This generalization is not true for the rest of the state; some children adopted the Hispanic culture and others an Anglo culture. Phoenix historian Bradford Luckingham, in his discussion of the Mexican culture of Phoenix, did not even discuss intermarriages.[28] Juanita Fellows’ children were some who chose the Anglo culture; each of her children married Anglo spouses.[29]

Janetta Ann McBride Ferrin

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Janetta Ann McBride

Birth: December 24, 1839; Church Town, Lancaster, England

Parents: Robert McBride and Margaret Ann Howard

Marriage: Jacob Samuel Ferrin; March 29, 1857

Children: Olive Fidelia (1858), Samuel S. (1859), Susanna Jane (1861), Robert McBride (1864), Janetta Ann (1866), Margaret Alice (1869), Sarah Elizabeth (1871), Jacob (1873), Edgar Ebenezer (1875), William Howard (1879), Charles Ether (1881)

Death: December 29, 1924; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Janetta Ann McBride was born in Church Town, England, December 24, 1839. Her parents’ home was used as a meeting house, and it was also a home to the elders. She was blessed and named by Brigham Young. They moved to Isle of Butte, Scotland, when she was six years old. While there she attended the School of Industry and graduated at the age of eleven years. She was in poor health, so she moved to her grandmother’s place which was located near the sea. She went over to a neighbor’s place to do some crocheting. Upon her return (to home) she found her grandmother burned to death. Her dress had evidently caught on fire. Her other grandmother was burned to death, too.

Janetta Ann McBride Ferrin. Photo courtesy of the International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Janetta Ann McBride Ferrin. Photo courtesy of the International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

At the age of thirteen, she moved back to England and at the age of fourteen was an apprentice to a dressmaker for two years. Her folks had always wanted to come to America and to Utah. It was not until 1856 that they got to come to America and to Utah. Word came to them that they could go by the Perpetual Emigrating Fund if they would go with the handcart company. They left England at Liverpool for America in the spring of 1856 and landed May 30 at Boston, Mass.

They came over on the ship Horizon and had good weather all the way over, but ran into a fog which was so dense that the candles would not burn. They kept the fog horn blowing for three days. They went to Boston and on to Iowa City by rail.[30] When they passed through Buffalo, [New York] on the Fourth of July, the citizens were having a great celebration, while the poor emigrants were crowded into box cars. Everything was supposed to be ready for them to leave when they arrived, but through some misunderstanding, nothing was ready. They had to walk from the railroad to the company grounds which were two or three miles away. It was raining very hard, and the mud was deep. They had to stay there about two weeks before the handcarts were ready. Then they set out on a three-hundred-mile journey pulling their handcarts with them. They crossed the Missouri River on a ferry boat at Florence. They had to stay there to recruit and fix things before continuing their journey.

They left Florence on the 25th day of August on a thousand-mile journey to Utah.[31] Each cart had baggage for seven people, which weighed seventeen pounds. There were also 100 pounds of flour, tents, and poles, cooking utensils, and what scanty food supply they had. In Robert McBride’s family there was no tent, but they had three carts when they left Florence. Janetta Ann’s mother took sick as soon as they left Florence and was sick all the rest of the way. The hardships were so severe that as they neared the mountains many of them lost their lives. Indians visited their camp soon after they left Fort Laramie but made no trouble.

It began to snow at the upper crossing of the Platte River. It was cold and stormy that night when Robert McBride went to the tent. During the night he died and was buried with twelve others who had died during the night.[32] All thirteen were buried in the same grave. The cause of the deaths was exposure and starvation.

They traveled in the snow from there to Devil’s Gate. At the upper crossing of the Platte, they had just one-quarter pound of flour a day and only provisions enough to last for three days. Janetta used to save her crusts and keep them in her pocket and give a few crumbs at a time to her younger brothers and sister who were walking, to coax them along.

One night, Peter McBride [Janetta’s six-year-old brother], who was not feeling well, was allowed to sleep. When the men started to take down the tent in the morning they found Peter lying on a quilt with his hair frozen to his quilt. They thought him dead, but he awoke and they had to thaw out his hair before continuing the journey. Several mornings Janetta’s hair was frozen to the ground.

When crossing the Sweetwater River, Janetta had to make several trips. First, she pulled her handcart across, then she went back and carried the children across, then she went back across, and this froze her clothes stiff and she could hardly walk.[33] The provisions were almost gone and the men were debating whether to turn back or keep going. At the upper crossing of Greasewood Springs, Joseph A. Young and two other men met the emigrants with words that teams of provisions were on their way from Salt Lake City.[34] They were told that if they could make the main Greasewood Springs there would be teams waiting there for them with provisions. They thought they could make it in two days, but they were five days, for the snow and mud was so bad they could not travel as fast as they first thought they could. When they arrived there, only three teams were there, and they had no supplies. As they moved forward, their movements became merely mechanical, and they pulled their carts forward from the force of habit with no hope for the future.

About one-fourth of those who had started with the company had been left on the trail [had died]. Those that [survived] were in a serious condition, for most of them had fingers and toes frozen. Some were very sick. They reached Devil’s Gate the first week in November. When they got there they discussed whether to go on or stay there in the mountains until the teams were rested and the snow was gone, but help came and they started on. They had to abandon their handcarts here, for they could not take them further.

As there were not enough teams to take all of them in wagons, some of them walked up the steep mountains. The snow was two or three feet deep and they were all bare footed. Janetta walked with those who had to walk.

They camped at Fort Bridger two or three days to rest up the teams that came to meet them. They reached Salt Lake City, November 20, 1856. Janetta, her mother, her sister, Maggie, brothers Heber, Ether, and Peter all reached Salt Lake City alive and, with the exception of her mother, all were alive when she gave this story to my aunt in the year of 1924.[35]

The family stayed in Salt Lake City one night, then went on to Ogden, where they made their home with Jacob Samuel Ferrin’s father. Jacob’s mother was dead, and he had a family of grown brothers. Janetta’s mother cooked and kept house for them. Janetta married Jacob Samuel Ferrin, March 29, 1857, at Ogden City, Utah. When Johnston’s Army came and tried to oust the Mormons, Janetta and her brother Heber took her six-weeks-old baby Olive Fidelia and with a team composed of two cows with calves, which caused a lot of trouble, and a horse in lead went to Provo with other families. Jacob Samuel Ferrin and some of the other men stayed in Ogden, so if the army came they intended to burn the house and destroy everything so that the army could not have it. They camped at Provo until July.

In the year of 1881, Jacob and Janetta started to move to Arizona. Janetta drove a team with a six-month-old baby in her arms. The baby was Charles Ether Ferrin of Thatcher. They had two wagons and some cows, which they sold at Beaver Head. They came through Flagstaff, which at the time was nothing more than a few canvas tents thrown up for protection. They passed through Phoenix, then to San Carlos to follow the Gila River up to Pima.[36]

Her husband was killed by the Indians on the San Carlos Indian Reservation, July 19, 1882, and left her a widow with eight unmarried children. Robert was the eldest, and he had to make a living for the rest of the children and his mother. They had a lot but not a house. The men of the town helped them build a one-room adobe house.

She was a teacher in the Relief Society for forty-nine years and was president of the Primary for about as many.[37] She was separated from three of her children, who were married in Utah. It was about fifteen years after his marriage before Samuel, her son, came in a covered wagon to visit her. She went back with him to Utah to visit with her other children up there. She was a good manager and a good housekeeper and always had something in the house to eat. She made very good pies and good mincemeat.

While she was in Utah, the boys bought a three-roomed frame house because the adobe house was cracked and was not safe. Because of her previous training, she was a very good seamstress. She was a very good singer and belonged to the choir for about thirty years. One of her virtues was to say nothing bad about any one.

She died on December 29, 1924, and her family and relatives honor her name.[38]

Ellis and Boone:

The story of Janetta Ann McBride Ferrin has recently been published in the second volume of Women of Faith in the Latter Days.[39] However, the part of Ferrin’s story, as related here, that could be expanded is the time in Utah immediately before coming to Arizona, their early experiences in Arizona, and the death of her husband. The Ryder Ridgway files note that the family lived in Huntsville, Eden, and then Pleasant View, Utah, before coming to Arizona. “Jacob Samuel Ferrin farmed, raised fruit and vegetables of many kinds. He also raised cattle, pigs and sheep. The sheep were sheared and the wool was carded into yarn by his wife, Janetta Ann, and then woven into material which was made into clothing for their family. Also tents were made for camping. Janetta was an excellent seamstress and an industrious woman.”[40]

When the family arrived in Arizona, Ridgway noted that “Jacob Ferrin found an empty log cabin and moved his family into it. At that time the streets were full of mesquite trees. There was no work in the town where a man could make a living for his family, so Jacob took up freighting, as his neighbors were doing. They went to Globe and filled their wagons with ore from the mines, then hauled it to Bowie and Wil[l]cox and traded the ore for what was needed in Globe and Smithville.”[41]

It was this practice of freighting through Apache territory that led to Jacob Ferrin’s death. McClintock wrote, “July 19, 1882, Jacob S. Ferrin of Pima was killed under circumstances of treachery. A freighting camp, of which he was a member, was entered by a number of Apaches, led by ‘Dutchy,’ escaped from custody at San Carlos. Pretending amity [friendly, peaceful relations], they seized the teamsters’ guns and fired upon their hosts. Ferrin was shot down, one man was wounded and the others escaped.”[42] And so, Janetta was left a widow only six months after coming to Arizona.

Settlers in the Gila Valley suffered much more from Native American aggression than did Mormon pioneers in other areas. The persistent memory of these incidents (including several times when settlers such as Jacob Ferrin were killed) is best illustrated with the furor which arose when a mural was to be painted in the new post office at Safford during the New Deal era. Competition for post office murals was nationwide and fifty-seven proposals were received for the Safford mural. The winning artist was Seymour Fogel of New York City whose proposal showed four Native American ceremonial dancers with desert mesas in the background. Although Fogel intended this to be a peaceful scene, Betsy Fahlman noted that Gila Valley residents “reacted to his design with intense hostility.”[43] By way of explanation, Senator Carl Hayden wrote, “The Safford Valley was the center of the most serious, bloody, and longest continued Indian depredations in the history of the United States,” and H. P. Watkins, secretary of the Graham County Chamber of Commerce, added, “In their early struggles so much trouble was encountered with the Indians . . . that any thought of depicting their chief enemy in their public building is distasteful to their generation.”[44] Eventually, Fogel scrapped his original plan and painted six panels which were more palatable to the community; he stated, “Much to my surprise the local townspeople are extremely enthusiastic and impressed,” so all were satisfied in the end.[45]

Adelaide Margaret Smith Fish

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Adelaide Margaret Smith

Birth: February 13, 1857; Parowan, Iron Co., Utah

Parents: Jesse Nathanial Smith[46] and Margaret Fletcher West

Marriage: Joseph Fish;[47] May 1, 1876 (div)

Children: Horace Nathaniel (1877), Silas Leavitt (1880), Joseph Smith (1882)

Death: October 29, 1927; Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Burial: Wasatch Lawn Memorial Park, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah[48]

Adelaide Margaret Smith, daughter of Jesse N. and Margaret Fletcher West Smith, was born in Parowan, Iron County, Utah, February 13, 1857. Having been born soon after Parowan, the pioneer town of southern Utah, was settled, her childhood was spent on the frontier, and the advantages of schooling were, of course, limited. However, she enjoyed Parowan and the social advantages that the town afforded.

Theatrical entertainments were very common during her girlhood and early womanhood, and some of the members of the troupe became good actors. Adelaide participated in the drama and gave dramatic readings. Like her mother before her, she was gifted in this line.

Adelaide Margaret Smith Fish. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

Adelaide Margaret Smith Fish. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

She was married May 1, 1876, in Salt Lake City, Utah, to Joseph Fish. In 1878 they came to Arizona in Jesse N. Smith’s company, which was organized according to the wishes of President Brigham Young in his plan to carry the outposts of Zion farther into the wilderness. They arrived in Snowflake, January 16, 1879, six months after the purchase of the place by William J. Flake from Mr. Stinson. Those living today can hardly get the picture of the hardships experienced by the pioneers of that day. The winds were so fierce that they had to cover their faces with cloth for protection when out, and at times travelers could not see their way before them. There were times when there was actual suffering because of scarcity of food. There were Indian scares, thieving and murderous outlaws, religious persecutions, sickness with no skilled medical assistance, and all the hardships and privations common to a pioneer country. But hearts were strong, and morals were clean in those pioneer homes, even though comforts were few. Adelaide did her part in that pioneer period, both in the home and as a community worker.

The following instance is cited to illustrate conditions at that time. Nathan B. Robinson was killed by Apache Indians fourteen miles south of Snowflake on June 1, 1882, near the Reidhead Ranch, now Lone Pine Reservoir.[49] The Apaches were then on the war path. Just five days later Adelaide’s youngest son, Joseph, was born. Her husband was away at Forest Dale at the time with a posse of men who were protecting the rights of the settlers in the Indian warfare. Her baby was born in a little log house. All the neighbors and friends were away at the time and Adelaide was left alone. She had no doctor, no nurse, no help whatever at the time of the birth. When help finally arrived, mother and babe were found lying on the floor.[50] Through this one severe experience, Adelaide was an invalid the rest of her life. Neither did her health permit her to have any more children. She had three children, Horace, born in Parowan, Utah, and Silas and Joseph, born in Snowflake, Arizona.

She held many positions of honor and trust both as a church worker and in the government service. On November 7, 1891, she assumed the responsibility of the United States Military Telegraph Office at Snowflake. She was not the first operator. Her son Horace was the operator from November 7, 1891, to July 11, 1893. Her son Silas was operator from that date to October 2, 1899. Her son Joseph was next the operator to October 10, 1903. She then became the telegraph operator in name, having only assumed the responsibility before this date because of her sons being in their teens. She learned telegraphy from her sons and held the position for her boys as telegraph operator. When the government discontinued its military post at Fort Apache, she was honorably discharged with the commendation of the government for her long service.

For five and one half years she operated the telephone exchange at Snowflake, the first one installed there. She was “Central” from March 8, 1907, until September 28, 1912. For almost thirteen years she served as postmistress of Snowflake. She was appointed by President William McKinley May 22, 1901, but did not take charge of the office until July 1, 1901, when the transfer was made. She resigned this position because of ill health January 10, 1914, and received the rare tribute from the government of having made a perfect record in her work and her financial accounts. Ill health caused her to refuse an urgent request that she continue longer as postmistress.

She also held positions in the ward and stake Mutual and Relief Society organizations. She was always public spirited and interested in the welfare and progress of the community.

During the time that Silas was telegraph operator, she and Silas and Joseph were alone at home. Horace had gone with his father to Graham County (Arizona), and it was during this period that Adelaide was practically an invalid, having to spend much of her time in bed. Silas and Joseph were both going to school, and when there was a call on the telegraph line (the calls were only occasional because the line was short and the business was greatly limited) she would hang a cloth on the porch and since the schoolhouse was just across the street from her home Silas would watch the porch for the signal and sometimes he would miss the game of ball during the recess period by taking a telegraphic dispatch instead.

The two boys had to do most of the cooking, baking the bread, and washing the dishes during this period. The diet was generally mush and milk for breakfast, bread and gravy at noon (the boys hastily cooking the gravy as soon as they came home from school), and after school they would wash the dishes and then have bread and milk for supper.

No matter how much she needed the boys, she insisted that they attend school regularly and prepare their lessons each evening. She wanted her boys to go to college, and it was undoubtedly her ideal which resulted in her three boys all going off to school after completing the work given in the local school, and the two younger ones receiving degrees from universities. Her boys also claim that she was so insistent on moral ideals that even when they were away from home they always felt her presence and the influence of her ideals enabled them to resist many temptations.

She never had good health, but she succeeded in accomplishing a vast amount of work. Many times her condition was such that her life was despaired of, but she learned to take care of herself, to rest when fatigue overtook her, and to make the proper selection of foods.

Her ambitions to do something in spite of her illness led her to dig deep into many fields of endeavor. She learned to make wool flowers and later took up the making of wax flowers. She became so skilled in this art that her neighbors induced her to organize classes and give instruction in making wax flowers. Not only was she gifted in making artificial flowers, but she took a special interest in growing natural flowers, always having a flower garden in front of her house. She imported purebred Plymouth Rock chickens, and gave other citizens of the community a start. She took prizes at the county fairs on her cooking.

She never had very much of this world’s goods, and early learned the value of a dollar and made it do double duty.

Being of a serious and religious turn of mind she had a lifelong desire to work in the temple, but she almost despaired of ever achieving this ambition because of limited finances and her poor health. However, after the military telegraph office closed, she moved to Salt Lake City and realized the fulfillment of her heart’s desire, that of working in the temple. Here she lived for five and a half years, devoting her life to genealogical and temple work. She did extensive research in genealogy and made many friends among the temple workers and among the members of the Fourteenth Ward, where she was an active worker.

Her last years were happy because of the realization of a lifelong desire, and the satisfaction of doing original research work in genealogy, especially the Aikens-Whitcomb line. She did temple work herself for deceased relatives and succeeded in getting relatives and friends to act as proxy for many more.

She died October 29, 1927, from injuries suffered in a street car accident in Salt Lake City. It was a sad ending of a life acquainted with physical pain, with pinches of poverty, and with heartaches. She was a polygamous wife and this involved much self-denial, as only those pure-minded religious devotees can comprehend. These experiences, however, mellowed her soul and sweetened her disposition. It is possible that she did not suffer much pain in her passing, for she apparently never regained consciousness after the accident. Again her independent spirit would have suffered had she lived to become a helpless old woman.

So passed a soul as pure as the angels and devout in her belief in the efficacy of prayer and in the eternal life of man.

Ellis and Boone:

Adelaide Smith married Joseph Fish as his third wife and found it difficult to live polygamy. On March 13, 1905, she divorced Joseph, and, as with most other divorces, RFC fails to mention this one. It seems impossible to know Adelaide’s reasons for wanting the divorce and useless to speculate. This November 11, 1902, entry from Joseph Fish’s journal tells of the divorce but of course does not represent her thinking:

As I have stated my wife, Adelaide, had been disaffected for several years, she told me at this time that she wanted a divorce. I told her that it was not my wish, that I had always loved and respected her, and such a move was far from me, but that I would not stand in the way of her, having one, as I wanted all my family to be happy if they could, and I did not wish to stand in the way of their happiness. I was willing to live with her or that she should have a divorce if she wished. I asked her for what reason she wished a divorce and she said that I was too poor, and ought to have considered that before I married her. I fully realized that I was not wealthy but still we were about as well off as many of our neighbors. I had got the government Telegraph Company to put in an office in her house, one room of it, and had paid to have Horace learn to run it some years before, and the government paid a high rent on the room, and Silas and his mother both learned after, so that when Horace left one of the boys or their mother carried on the business of the office which of course was not much, but it was quite a source of revenue, as the government furnished lights and many other items besides the rent. Besides this I gave her $30 a month out of my $75, and I paid all the taxes, tithing, donations, etc. . . . She soon after got a divorce. . . . In her statement she said that there were faults on both sides, and I was willing to admit this and asked her if this was the case if there was not a chance for a reconciliation. She said no, that there was no chance, and she seemed happy in taking the step she had.[51]

Joseph Fish was prosecuted for living polygamy in Arizona in 1884, and he took one of his families to Mexico in 1885, although they did not stay there permanently.[52] After the Manifesto, the Arizona political establishment adopted a “live and let live” policy, thinking that with no new polygamous marriages the practice was dying out. However, in 1905, Senator Fred Dubois from Idaho, wellknown for leading the opposition to seating Reed Smoot in the Senate and also for trying to disenfranchise the Mormons, traveled to Arizona and pushed for further prosecution of Latter-day Saint men living polygamy. Adelaide Smith Fish was one of the women to testify against her husband.[53] Ten men were arrested, and the case was heard on December 8, 1905, in Prescott. Joseph Fish wrote, “We were fined $100 each. . . . I sent my $100 and got a receipt. . . . We were now free again and felt as if we had got another trouble off our hands. This all was the work of Dubois. Our local officials did not care to bother with it but were forced to do so.”[54]

Carrie Lindsey Flake

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Carrie Lindsey

Birth: July 7, 1887; Greenbrier, Faulkner Co., Arkansas

Parents: Jacob Isaiah Lindsey and Mary Elizabeth Fair

Marriage: John Taylor Flake; October 5, 1910

Children: Burton Taylor (1911), Zona (1913), Melba (1917), William Lindsey (1920), stillborn daughter (1923), Cathleen (1927), Chad John (1929)[55]

Death: July 26, 1938; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Just a flash from life here to life over there, not a moment’s secession [cessation] of activity, with a smile on her lips and a flash in her eye, she crossed over the narrow margin between here and there. Always doing something for someone, it is only natural that her last thought and action was service, safeguarding someone else. A terrific storm had blown down a live electrical wire across the roadway. She had gone out to warn passersby and was electrocuted. Greater love hath no man than that he will give his life for a friend.[56] Someone was in danger; she must warn them, and she did at the cost of her own life; such is the closing story as far as active participation in this mortal existence of the beloved Carrie Lindsey Flake.

Carrie Lindsey was a daughter of the Old South, with all the fine qualities and traditions of that aristocratic race, born in Greenbrier, Arkansas, while her father and mother, Jacob Isaiah and Elizabeth Fair Lindsey, were there from their Mississippi home visiting relatives.

This was July 7, 1887. Her parents had heard and accepted the gospel of Jesus Christ. When Carrie was only four years old, they journeyed to the West to join the people of their choice. They landed at Snowflake, Arizona, on her mother’s birthday, December 3, 1891. They were only here two months and twelve days when her father died.[57]

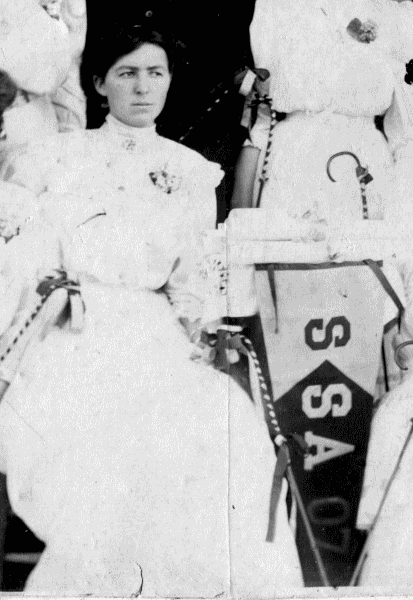

Carrie Lindsey Flake when she graduated from the Snowflake Stake Academy in 1907. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Museum.

Carrie Lindsey Flake when she graduated from the Snowflake Stake Academy in 1907. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Museum.

As soon as Carrie was old enough, she entered into the social life of the town; she sang in the choir and in a glee club, was chorister of the Young Ladies Association. She had such a fine sense of harmony that she could assist with any part in a chorus that needed strengthening. Her ability to portray any part on the stage made her invaluable in home dramatics.

Carrie was a most loving and dutiful daughter, assisting her widowed mother by early going out to work in homes, where she was a universal favorite because of her ability to make friends. A Sunday School and Primary teacher for many years, and later an assistant to her husband in the management of the dances and movies, she has won a place in the lives of the young people of the town that few ever have.

On October 5, 1910, in the Salt Lake Temple, Carrie became the wife, the pal, and the constant companion of John T. Flake, and the daughter in very deed of Lucy H. and William J. Flake. How she loved and exchanged banter with this father-in-law of hers, and something—was it the tie of southern blood—made them enjoy each other very much.

Other couples have been married longer but none more completely than John and “Dolly,” as he affectionately called her. Always together if it were possible, on trips with him where duty or pleasure called, a complete union and understanding. Six children have blessed this favored pair. Their home has always been one of love, peace, and congeniality.

Truly Carrie lived in a house by the side of the road, and has been a friend to all; rich and poor, high and low, Mormon, Gentile and Indian, and counted among her friends was Bah Hah, chief of the Apaches.[58]

Carrie was an untiring reader and her library contained some of the choicest gems of literature. She loved nature and the great outdoors. She was famous for her gardens of flowers and vegetables. Her life was spent in this little town, her efforts given to its advancement. As the wife of a bishop’s counselor and scoutmaster, and the other positions held by her husband, she was truly a helpmeet. No sacrifice was too great to give to her children the advantages of higher education and a mission.

No more beautiful passing could have been planned. From an abundance and ardent love of life Carrie has gone on, to a larger sphere of action.

Carrie Lindsey Flake died July 26, 1938. The funeral today, July 28, 1938, was perfect in every detail, as was in fact, her passing. I began a sketch of her life thus—just a flash from her life here to life over there—not a moment’s [cessation] of activity. With a smile on her lips and a light in her eyes she crossed over the narrow margin between here and there. Such is the closing chapter, as far as her active participation in this mortal existence of our beloved Carrie Lindsey Flake.

The decorations, the singing, the speaking, the prayers, the tributes from her old crowd, her Primary boys, and the high priests and their wives were all beautiful and touching. We go on from where we left off. Such is life, we pause briefly in the mad whirl long enough to bury our dead, and then on we go. We must not stop, if so we will lose our place in the procession that rushes on hither and thither. No one knows how or why.

Carrie Lindsey Flake

’Twas the evening of life when she went away.

Her day had been long and sweet—

So sweet that scarce had her hair turned grey,

Her gladness seemed quite complete.

Her smiles brought pleasure wherever she went

And her song, so filled with love,

Made one think the angels, all gladly content

Had come from the throne above.

That they’d brought a comforting word for all

And given to each one near

The strain was low, but ’twould gently fall

’Twas plain for all to hear.

The sweetest strains her glad voice trilled

Were the songs of Motherhood.

When that little log cabin with joy she filled

To quiet her restless brood.

There were other songs too, that she sang quite oft

’Twas the poor who heard them best

She would sing “Come, come” in a tone so soft

“Come to the old home nest. There’s a bite to eat for each needy one

Who has journeyed far today

There’s a wrap so warm for the tired son

Who has traveled along the way.”

In the busy life she lived down here

There was time for prayer each day,

And the authors she studied and knew so dear

Left little time for play.

She was busy right up to the hour she left

And served all who came her way,

’Tis a large and grateful throng she will meet

The morn of Judgment Day.

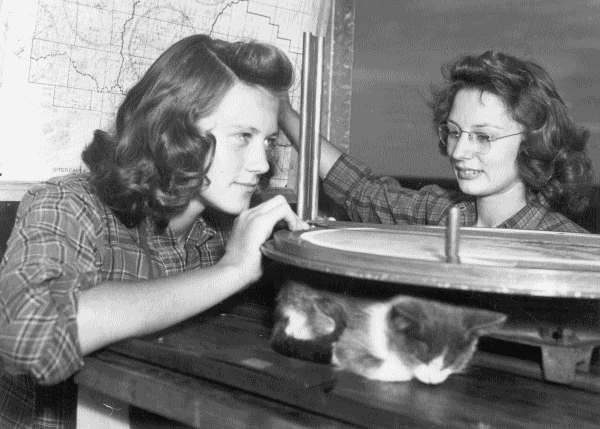

Another of the women who "manned" Forest Service lookouts in 1944 was Wanda Turley (right), shown here with her sister Marilyn (granddaughters of Mary Agnes Flake Turley, 727). Two lookouts, using an Azmuth Ring and maps, could pinpoint the exact location of smoke from a forest fire. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

Another of the women who "manned" Forest Service lookouts in 1944 was Wanda Turley (right), shown here with her sister Marilyn (granddaughters of Mary Agnes Flake Turley, 727). Two lookouts, using an Azmuth Ring and maps, could pinpoint the exact location of smoke from a forest fire. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

Ellis and Boone:

When the Lindsey family came to Snowflake, they were very poor, and William J. Flake helped by building them a home on the Kartchner lot. The family became an important part of the community. Not mentioned in this sketch was the fact that Carrie and John T. Flake’s courtship was interrupted by John T.’s Northern States Mission. John T.’s hospitality was well known. “When Stake Conference time came along, the people were expected to invite visitors from other communities home for dinner, John T. always waited until others made their choice, and then he would invite those neglected by others and take them home, treating them as though they were visiting authority.”[59] Although this was written about John T., it was Carrie who prepared the meal, entertained the guests, and helped them feel welcome.

Carrie Lindsey Flake. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Carrie Lindsey Flake. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Because Carrie Lindsey married RFC’s brother, John T. Flake, it was Clayton who wrote this sketch and the memorial poem for Carrie’s funeral. Clayton also included a sketch of the life of John T. Flake in PMA, and told of his second marriage to Sarah Annis Jackson of Pinedale. Annis, a daughter of Hannah Jackson, 313, was born in 1905 in Pinedale. She wanted an education and so came to Snowflake for high school, boarding with a couple who expected her to milk the cow morning and night. “At first she was deathly afraid of the beast,” wrote Jennifer Peterson when she interviewed Annis in 1984, “but then she got up enough nerve to go in the barn and sit down to her task. The minute she started, the animal kicked and snorted and Annis ran from the barn to her ‘aunt’ who gave her a white apron and told her as long as she wore it, the cow could be calm. The apron worked, and her troubles with the cow were over.” Annis told of being the only girl in the geometry class, and after graduation, she taught school in Snowflake for many years.[60] In 1944, the year before she married John T. Flake, Annis spent the summer as a forest lookout. The Holbrook Tribune-News noted that due to the shortage of men during World War II, “of the six forest fire lookouts on Sitgreaves National forest, three are ‘manned’ by women” and two of these women were teaching school during the previous winter.[61]

Christabell Hunt Flake

Ida Flake Willis

Maiden Name: Christabell Hunt

Birth: August 27, 1864; Beaver, Beaver Co., Utah

Parents: John Hunt[62] and Lois Barnes Pratt[63]

Marriage: Charles Love Flake;[64] September 16, 1885

Children: Marion Lyman (1886), Grace (1889), Ida (1890), Marshall Hunt (1891), Charles Love (1893)

Death: November 19, 1934; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

My mother, Christabell Hunt Flake, was born in Beaver, Utah, on August 27, 1864, and was the fourth daughter of John and Lois Pratt Hunt. The home she grew up in was one of love and refinement. Their mother taught them correct English and proper manners.

She was a very bashful little girl and depended on her older sisters to do all the talking and entertaining when company came. She had a beautiful singing voice and always enjoyed singing with the other members of the family.

While she was still a small girl, her family left Utah and moved to New Mexico to a small place called Savoia. During the winter, they were exposed to smallpox. The younger children had serious cases of it, but the older girls had been vaccinated in San Bernardino, California. An old Navajo Indian they had made friends with would bring them meat, in spite of the fact that Indians were in mortal terror of smallpox. He would ride up to the fence, wait until he saw someone, then drop the meat in the snow and ride away as fast as his horse could run. The meat was greatly appreciated.

Belle Hunt Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Belle Hunt Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

While still living there, Grandfather Hunt received a call to go to Snowflake, Arizona, to be the bishop of the newly formed ward there. He and Grandfather Flake had been close friends for many years in Beaver, so when Grandfather Flake bought the Stinson Ranch for a town site, he asked that John Hunt be made the bishop. In turn, Grandfather (William J. Flake) was made first counselor. They worked together for thirty years in the Snowflake bishopric with the help of several second counselors.

Mother’s first great sorrow came when her mother died on March 9, 1885. She had always depended on her so much that she felt completely lost without her sweet influence.[65]

That same year, on the 16th day of September, she married Charles Love Flake. He was a charming young man of many talents and was just what she needed to make life worthwhile. They traveled to St. George, Utah, by team and wagon to be married in the temple there, leaving Snowflake on her birthday. She always told us what a wonderful trip it was.

When they got back and had given a wedding dance for the town people, they were completely out of money but started housekeeping in a little log house across from her folks. For a while she cooked their meals over the fireplace. However, that didn’t last long as Father was a wonderful provider, and in a very few years they were well fixed financially.

Their little daughter, Grace, died in December 1890. Two years later in December 1892 Father was killed by an outlaw. He and his older brother, James M., had gone to arrest this desperado, who had robbed a bank in Grants [San Marcial], New Mexico. Father was Justice of the Peace and the only law officer in town. It was a terrible tragedy; Father was killed, and Uncle Jim barely escaped with his life. His face was all burned by the powder, and he lost the sight of one eye.[66]

Father was mourned by all who knew him. Even Chief Alchesay of the Apache Indian Tribe and several of his warriors came to the funeral.[67]

Mother was only twenty-eight years old and had three small children; Marion, myself, and Marshall. Our brother, Charles L., was born six months later on June 12, 1893. He was the joy of her heart. He was such a happy boy and could always see and appreciate the funny side of life.

In spite of sorrows, Mother had a busy, happy life. She loved the beauties of nature, the birds, flowers, streams, and animals. She was especially fond of horses and could handle a team as well as almost any man. She always had a good saddle horse, demanding and receiving respect from all who knew her.

Charles Love and Christabell Hunt Flake, c. 1885. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Charles Love and Christabell Hunt Flake, c. 1885. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

In World War I, she was called upon to make another sacrifice. Charles was killed in far-away Siberia. He was stationed with the U.S. forces there guarding some coal mines. The war was over in November of 1918, but these soldiers had not yet been released in June of 1919. They were fired on from ambush by a rebel gang.[68]

His release papers, also the telegram telling of the birth of his baby daughter, were found on his desk. It is strange that fate would decree that his father didn’t live to see him nor he live to see his daughter. Sometime we’ll understand.

Although his death was very hard for Mother to accept, she faced it, as she did everything else, with admirable courage and received solace in her devotion to his wife, Ruth, and their daughter, Marjorie.[69]

Mother never had to worry about finances due to the farsightedness of our father and the care Uncle James M. Flake took of her property. He and Father were business partners. They owned Flake Brothers General Merchandise Store, freight and mail contracts, cattle and horses, and farms. Her own brothers and sisters and Father’s family were always mindful of her comfort and did all they could to ease her loneliness.

Just after her seventieth birthday, she decided she was tired of living alone; she had been a widow for forty-two years. When she got a bad cold, which developed into pneumonia, she refused to be helped and in just one week she passed peacefully away November 19, 1934.

She is buried in the Snowflake cemetery by the side of her beloved husband and among so many of her friends and dear ones.

Ellis and Boone:

When John and Lois Hunt brought their family to Snowflake from New Mexico, their daughters were thrilled. In New Mexico they had lived in a relatively isolated area, and with the move to Snowflake each daughter now enjoyed the company of other young people.[70] Christabell, usually called “Belle,” and two of her sisters, Annie and May, soon found husbands. These three sisters then raised their own families in Snowflake and participated in the Snowflake Relief Society organization at every level. Also their younger sister, Nettie Hunt Rencher, eventually returned to live in Snowflake.

The care that William J. Flake, and later his son James Madison, took of the widows of Snowflake was not just limited to Belle Flake. William J. and James M. Flake would butcher cattle and then deliver the meat to these women. In addition, Snowflake became known for the Widow’s Wood Dance, also called the Thanksgiving Wood Dance. When Julia Ballard (49) was Relief Society president, she became concerned about Sister Farley, a missionary “widow,” who had no wood for the winter. Ballard enlisted the men and boys of the town and the next week Sister Farley had seventeen loads of wood. This custom soon morphed into a Thanksgiving activity where the men and boys assembled early in the morning to cut and deliver wood earning a ticket to the dance. Women of the town made Thanksgiving dinner and baked pies, and all had a good time that evening at the dance.[71]

Lucy Hannah White Flake

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[72]

Maiden Name: Lucy Hannah White

Birth: August 23, 1842; Walnut Grove, Knox Co., Illinois

Parents: Samuel Dennis White and Mary Hannah Burton

Marriage: William Jordan Flake;[73] December 31, 1858

Children: James Madison (1859), William Melvin (1861), Charles Love (1862), Samuel Orson (1864), Mary Agnes (1866), Osmer Dennis (1868), Lucy Jane (1870), Wilford Jordan (1872), George Burton (1875), Roberta (1877), Joel White (1880), John Taylor (1882), Melissa (1886)

Death: January 27, 1900; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

So nigh to grandeur is our dust,

So near to God is man,

When Duty whispers low, “Thou must,”

The youth replies, “I can.”[74]

The above truism seems to apply to all of the Arizona Pioneer Women but particularly so to the life of this one, Lucy Hannah White Flake.

She was born in Knox County, Illinois, August 23, 1842. Her parents were Samuel Dennis and Mary Hannah Burton White. They had already accepted the gospel as taught by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, thus, Lucy was born a “Mormon.” Even her grandparents, the Whites and Burtons had joined the Church and left their Illinois homes for the gospel’s sake. Lucy remembered being held in the arms of her father and looking upon the faces of the murdered prophet, Joseph, and his beloved brother Hyrum, in Nauvoo.[75]

Lucy Hannah White Flake. Photo courtesy of Cleon Solomon.

Lucy Hannah White Flake. Photo courtesy of Cleon Solomon.

Brought up very properly by a schoolteacher mother, Lucy early learned the art of correct speech. She never permitted slang in her home if she could help it. She also learned the duties of the home, being the eldest of eight children. Many responsibilities were hers. It is no wonder, with such day-by-day training, Lucy was prepared to assume the duties of wife and mother at an early age. A little past sixteen she married.

Her parents endured the driving and mobbings the other Saints did, with the added sorrow of leaving Lucy’s precious little grandmother, Hannah Burton, in a wayside grave as they crossed the plains.[76]

Lucy was baptized in the Missouri River, where the ice had to be broken for the ordinance. She walked every step of the way, as did countless others who were driven forth from civilization by evil and wicked, designing men. The Whites arrived August 31, 1850, in what is now Salt Lake City.[77] They ate the last of their provisions on that day, which was her mother’s birthday. After visiting ten days with her mother’s people, the Burtons, who had come previously, John Griggs White and sons, Samuel Dennis and Joel, and son-in-law David Savage were called to settle Lehi which is forty miles south of Salt Lake City. John Griggs White had been sick all during the trip, and he died shortly after going to Lehi. Shortly after the death of Grandfather White, they were called again to move, this time to Cedar City. It was there that Lucy met her Prince Charming. The match-making Uncle Joel had it all arranged before the young folks had even met, so all they had to do was fall in love with each other.

Young William Jordan Flake was one of the young men helping to drive the loose horses from San Bernardino when that place was evacuated by the order of Pres. Brigham Young. Uncle Joel had gone to help bring the Saints back to Utah, along with Lucy’s father. When they returned they told Lucy of a very fine young man, William Flake, whom they had met. He was strong, manly, and had no bad habits. According to them he was a paragon of goodness. Young Mr. Flake was an orphan boy about nineteen years of age. His parents had owned a large plantation in the South and had many slaves. When his father, James Madison Flake, joined the Church in 1842, he gave the Negroes their freedom.[78]

William Jordan Flake, as they reported, was tall and well built. He was also well mannered and chivalrous as becomes a son of the South. This was quite an admission coming from a couple of Yankees.

Lucy had several suitors, but when she saw this southerner she fell victim to his charms, and they were married December 31, 1858, at the home of her parents in Cedar City. The marriage was performed by the Apostle Amasa M. Lyman whom William always looked upon as his second father after his own father’s death. Mr. Lyman’s home was in Beaver, so shortly after the ceremony Lucy and her husband went there to live near him.[79]

When these young people were married the word “obey” had not been omitted from the ceremony, so when her husband believed a thing was right and had to be, he usually found willing cooperation in his plans. Because William always had fine teams and conveyances, he was called by the Church to freight from California and also to assist in bringing emigrants from the East. Consequently, during the first years of their married life, he was at home very little. They had just begun to realize some of their dreams. They had a fine farm, good homes, and a good start in cattle and horses. When William went to the dedication of the St. George Temple, he received a call to go and settle Arizona. William already knew what Arizona was, having answered a call there in 1873 when one of their exploring party was drowned in the treacherous Colorado.[80] He knew the equally treacherous Indians were almost the sole inhabitants of this desert, cactus-covered, mountainous place called Arizona. Only his faith in the call of the Prophet Brigham Young would have made him consider the terrible sacrifice which he knew he would have to make.

When he and his second wife, Prudence, returned from the trip to St. George, they found Lucy slowly recovering from a terrible sickness.[81] There were times when her life was despaired of, but owing to her faith and the administration of the elders she was able to give birth to her tenth child, August 19, 1877, Roberta Flake, later Clayton.

Preparations were made in earnest to try to get away on their terrible journey before the snow fell. But it was October before they could start out. When their caravan was ready, the Flakes had six wagons loaded to capacity. These were drawn by nine yoke of oxen and seven span of horses. They had 200 head of cattle and forty head of horses. It took three months to make the journey.[82] Their first grandchild was born in an old covered wagon at Grand Falls on the Little Colorado River.[83] One of the most trying things of this terrible journey was when Lucy had to leave her fifteen-year-old boy in charge of the cattle that were too poor to travel. It was five months before they heard from him. Only through emigrants coming through did they receive any word of him. Great was the joy when spring opened up and the cattle were able to travel and her son Charles was restored to her arms.[84]

Their first camp was at Allen’s Camp on the Little Colorado.[85] Here the people were living in the “United Order.” The water in the river was so muddy that a barrel full of it left overnight would only produce about six inches of water clear enough to use for culinary purposes. Dam after dam was placed in the river. These were washed away by every little freshet that came down the river. The Flakes were so discouraged that one morning William saddled up his horse, bade Lucy goodbye, and told her there must be a better place in Arizona and if there was he would find it. Some of the people in the order called him an apostate because he would not submit to the conditions then existing. This and the absence of her husband were great trials to Lucy. The hardest thing that came to her was the sickness and death of her little three-year-old son, George, who passed away just an hour before his father returned.[86] A coffin was made for him from parts of one of the wagons, which with her own hands she painted and trimmed with one of her sheets. William’s grief at the loss of their son was equal to her own. There was only one ray of hope at this time, and that was that her husband had found a ranch that could be purchased if he could make the necessary payments. As usual, she stood by the side of her husband, urging him to buy the ranch, telling him they would pay for it someway, even offering to do the men’s washing to help.[87]

It didn’t take them long to put their wagon boxes back on the running gears and be off on their new venture. When they came to the clear waters of the Silver Creek, all who were able jumped out of the wagons, rushed to the stream, bathed their faces, and drank the first clear water they had seen since they left their home in Beaver.

Lucy made several trips back to her Utah home with her husband to get cattle and sheep on shares with which he paid the $12,000 debt on the ranch.[88]

On the first trip, they met Erastus Snow who was the Apostle to the outlying settlements. William told him what he had done and Elder Snow said, “I wish we had hundreds just like you.” He asked Lucy’s husband, William, whom he wanted to preside over the newly organized stake and if he, William, would make a good bishop. He answered, “No, but I know someone that will.” He then named John Hunt who became the bishop for thirty-five years with William as his first counselor. For president of the stake, William suggested two names, one of which, Jesse N. Smith, was selected as president of the Eastern Arizona Stake. Elder Snow told William that he had combined their two names, Snow and Flake, for the new settlement and wanted to know if that was agreeable. It was, and Snowflake it has always been.[89]

There was a large four-room adobe house and half a dozen smaller ones on the place. The Flakes lived in the large house known as the “White House.” It served as the first courthouse in Yavapai County. Yavapai was divided, Apache County was formed, and then it was divided and Navajo County was made. “The White House” was the first courthouse, the first post office, and the first meeting house in the new settlement. School was held in one of the smaller houses. Snowflake was the first all-night stop between Holbrook and Fort Apache, and all of the travel stopped at the Flake home.

Lucy served her church as counselor to the ward Relief Society for many years. She was also a teacher in Primary, Sunday School, and the Religion Class and was stake president of the Primary at the time of her death which occurred January 27, 1900.

She was the mother of thirteen children, five of whom died in infancy or early childhood. Among the most terrible trials that came into the life of this wonderful woman was when her husband was incarcerated in the Yuma Penitentiary for his belief and practice of plural marriage and because he would not desert either of his wives and families.[90]

Lucy always had implicit faith in prayer and in the promise of the priesthood, yet when her son Charles was shot down by a desperado, she could not reconcile herself, because he had been promised he would be the means of bringing thousands into the Church. He had already been the first missionary from the little town of Snowflake, had endured abuse and mobbing in Mississippi, even to having a bucket of tar poured over him. His labors in Mississippi had, in a way, been successful, but it was a trial to his mother when he was shot down in cold blood.[91]

Early relief Society workers in Snowflake; front (left to right), Mary Jane Minnerly, May Hunt Larson (394); back, Frances Reeves Willis (800), Mary Jane Robinson West (771), Lucy Hannah White Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Early relief Society workers in Snowflake; front (left to right), Mary Jane Minnerly, May Hunt Larson (394); back, Frances Reeves Willis (800), Mary Jane Robinson West (771), Lucy Hannah White Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

At the time of the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple, William and Lucy made the trip to Salt Lake City hoping she would recover from the terrible shock of her son’s tragedy.[92] On reaching Salt Lake they were met by their lifelong friend Francis M. Lyman who arranged that the first work done in the newly dedicated temple was the sealing of her first children, who had not been born under the covenant. William told his foster brother how the death of Charles had affected Lucy. Brother Lyman put his arms around her and told her how impossible that would be to have that prophecy fulfilled in this world, that he had been taken in his early manhood and was busy on the other side carrying out the work he was promised he would do by the patriarch. She returned home comforted to magnify the many duties that were hers. At her death at the age of fifty-eight, she was mourned by all who knew her. She had been promised by Eliza R. Snow that she would never grow old. This promise was fulfilled. On the beautiful day of her funeral, a sunshiny day in January, children from all over the stake came and marched to the cemetery to show their respect and love for their beloved leader.[93]

Ellis and Boone:

Two articles provide a more researched account of Lucy’s life, including quotes from her journals: Chad Flake’s chapter in Supporting Saints which discusses her trials with living polygamy and David F. Boone’s article in the Journal of Mormon History.[94] Boone wrote, “Early in 1894, Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jenson traveled through the settlements of Arizona in an ongoing quest to preserve the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His message to the Saints in Snowflake was, in part, an admonition to keep a personal journal. One who heard and heeded the invitation was Lucy Hannah White Flake. She noted: ‘The last of February [1894] Brother Andrew Jenson Chirch Historian came here to snowflake for church history[.] he incouraged every one to write a jurnal[.] I had wished a great meny times in the last twelve years that I had comenced to write in a jurnal[.] he incouraged it so strong that I have made this feeble effort.’ With this entry Lucy Flake, age fifty-two, embarked on an intellectual odyssey—making a record of her life.”[95]

Lucy Flake’s journal has been donated to the L. Tom Perry Special Collections and Manuscripts in the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University. In 1973, Chad Flake and Hyrum F. Boone made a typescript with some annotations. Lucy first wrote retrospectively of her life up to 1894 and then made daily entries. From these entries, it becomes easy to understand that Clayton’s To the Last Frontier, although subtitled Autobiography of Lucy Hanna White Flake, is simply a fictionalized biography.[96]

Prudence Jane Kartchner Flake

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Prudence Jane Kartchner

Birth: March 15, 1850; Cottonwood, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Parents: William Decatur Kartchner[97] and Margaret Jane Casteel[98]

Marriage: William Jordan Flake;[99] October 10, 1868

Children: Sarah Emma (1879), Lydia Pearl (1881), Joseph Franklin (1884), twins Augustus Mark and Jane Margaret (1886), Wilmirth East (1887), Annabelle (1893)

Death: February 8, 1896; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

In Utah, just south of Salt Lake lies a little vale that in the early settlement of that land was called “Little Cottonwood.” Here was born to William D. Kartchner and Margaret Jane Casteel Kartchner on March 15, 1850, a little baby girl.[100] She was the second daughter and third child to bless their home. Her father was of sturdy Pennsylvania Dutch stock, and her mother’s descent is from the royal families of Flanders, with known ancestors back to 1410.

When but a few weeks old, owing to unfavorable living conditions, baby Prudence took a severe cold which settled in her lungs, weakening them so that all her life when she took cold she had difficulty in breathing. This, however, did not seem to hinder her development and she grew into a very beautiful girl.

Prudence Kartchner Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Prudence Kartchner Flake. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Her girlhood was a very happy one, not that her family had much of this world’s goods. They were pioneers in very deed, reaching Salt Lake City only a few days after the company of Brigham Young.[101] They had spent some months in Pueblo, Colorado, where a sister had been born having the distinction of being the first white child born in Colorado.[102] Then they came on to the Salt Lake Valley. From there they went to “The Muddy” in Nevada, among the first settlers to that country. The taxes in Nevada at that time were exorbitant, so the settlements there were abandoned. The other places they helped to colonize were San Bernardino, California; Panguitch and Beaver, Utah; and later Old Taylor and Snowflake, Arizona.

There was a large family and each had to do his or her part in helping feed and clothe themselves. The father, William, was a blacksmith, the mother an excellent manager, but poor health early forced the girls to learn the homey arts of cooking, washing, candle and soap making, milking, making cheese and butter, carding, spinning, and weaving the cloth for their own and their brothers’ clothes. With all these tasks to do, one wonders how her girlhood could be very happy, and yet it was. All worked so congenially together. The girls were all good singers and sang as they worked. One would keep time with her cards—not chords—and Prudence danced back and forth as she spun the yarn. She was a fine step dancer, doing all the steps that were known at that time.[103]

The Kartchner brothers played the fiddle and guitar as did the girls, and one of them played the accordion. All whistled and sang, and the house was never dull. Wherever their home was, it was the gathering place of all the young people when their days’ tasks were done.

Because of her glad, joyous nature, Prudence was a great favorite. She loved to dance and sing and often sang in public. She made her family quite proud of her one night at a dance when she sang a song that went like this:

When I was a wee little slip of a girl,

Too artless and young for a prude,

The men as I passed would exclaim “Pretty Dear”

Which I must say I thought rather rude.

Yea, I did, so I did,

Which I must say I thought rather rude.

That brought a response from one of the young men in the dance, and then she came back with another song, and thus the evening went on in dance and song. There were stump speeches and comic ones, while the dancers caught their breath from the strenuousness of the quadrille and reels.

Prudence’s school days were spent in various places. Often she would only get three months schooling during the winter term. She always made the best of her opportunities. She was full of life and energy, and at school it taxed the most fleet of foot to catch her when at recess they played “Steal Sticks,” “Pomp-pomp-pull-away,” or “Town Ball.” At one time, one of the swiftest boys tried to catch her and, in attempting to dodge him, she slipped and sprained her wrist.

Her girlhood was spent in wholesome work and fun. She often called the changes for the quadrilles when her many partners would give her time off from dancing. A girl so popular was sure to have plenty of chances to marry, and Prudence was no exception. When she decided at the age of eighteen to marry, she accepted the offer of William J. Flake. It was a very romantic affair. He asked her to become his wife and to accompany him on the trip he was taking. Her family was moving to a new home, and she told him she would decide that night. That night was a momentous one for her.[104] When they came to the forks of the road the next day she got out of her parents’ wagon and her family went on without her. When her Prince Charming came along the road, she was waiting at the trysting place, and they went to the city of Salt Lake and were married. From there they went to his home in Beaver on their honeymoon.