E

Lenora Owens Skillman and Roberta Flake Clayton, "E," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 159-170.

Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar

Lenora Owens Skillman

Full Maiden Name: Lucy Jane DeWitt

Birth: March 28, 1861; Big Cottonwood, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Parents: Abel Alexander DeWitt[1] and Margaret Miller Watson[2]

Marriage: Joel Sixtus Eagar;[3] February 14, 1879 (div)

Children: Lucy Lenora (1880), Joel Sixtus (1881), Sara Huldah (1883), Sariah (1885), John Elmer (1886), Lovinia (1888), Leo (1890)

Death: July 16, 1922; Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Burial: Wasatch Lawn Cemetery, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

My memories of my grandmother, Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, do not center around Woodruff, Arizona, where she lived when I was young, but around the times she would visit us at the Gentry Ranger Station where we lived during the summer. Grandma wasn’t too well in those days, but well enough to take walks with us, and these walks almost always led to a beautiful aspen grove not too far from the house. A clear little stream ran past the grove, and we loved to go there. We would find a log to sit on, and Grandma would tell us stories and teach us the songs in the hymn book, and I still remember the words to many of them. Also we learned the story of Joseph Smith’s prayer in the Sacred Grove, as well as many other beautiful gospel truths in these Sunday Schools with Grandma.

Lucy Eagar with her parents and sisters; seated, Margaret Millar Watson and Abel Alexander DeWitt; standing, left to right: Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, Sarah Huldah DeWitt Christofferson, and Elizabeth Catherine DeWitt Russell, before 1904. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Lucy Eagar with her parents and sisters; seated, Margaret Millar Watson and Abel Alexander DeWitt; standing, left to right: Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, Sarah Huldah DeWitt Christofferson, and Elizabeth Catherine DeWitt Russell, before 1904. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

I remember the trips when we would go to Woodruff to get Grandma. The distance isn’t far today, but then it would take us nearly all day. We would start out at three o’clock in the morning, when the sky was still filled with stars, and would lie on the bed Mother made in the bottom of the spring wagon, and watch the stars fade and the morning come. We would usually stay in Woodruff a day or two while Dad went to Holbrook for supplies, then we would go home.

Grandma loved to sing, and Dad also had a good voice and liked to sing, so they sang together as we traveled along, and, of course, we sang with them most of the time, and the trip was fun.

My Grandma Eagar was Lucy Jane DeWitt, the oldest child of Abel Alexander DeWitt and Margaret Miller Watson. She was born March 28, 1861, in Big Cottonwood, Utah. Great-grandmother DeWitt (Margaret Miller Watson) was a sweet little Scotch woman, less than five feet tall, who learned of the gospel in Scotland and came across the ocean on a slow sailing vessel when she was only sixteen years old. She worked in Holyoke, Massachusetts, for two years to earn money for the trip to Utah. In Salt Lake City, she met and married Abel Alexander DeWitt when she was nineteen years old. The DeWitt family was a large one—twelve children—and Grandma Eagar was the oldest one. When she was twelve or thirteen years old, the family moved to Kanab, Utah.

Grandma Eagar’s childhood was a happy one, and the teen years spent in Kanab were also very happy years. Her beautiful singing voice brought her much joy and made her very popular with her associates. She formed many lasting friendships during these years, but in her great desire to be one of the crowd and do what they did, she made the mistake of her life by marrying a man she did not love. Some of her friends were going to be married in St. George, Utah. They were going as a group by team and wagon to be married in the temple there. It was quite a long trip from Kanab to St. George in those days, but it sounded thrilling, so she listened to the young man she had gone with several times, and to the others who were going, and joined the group and was married to Joel Sixtus Eagar in the St. George Temple on February 14, 1879. The trip was fun, but after she returned and began to think, she realized she had made a mistake. However, she was a brave and lovely person and decided not to let the world know any more than necessary about her troubles.

About a year after they were married, Great-grandfather DeWitt, his family, and others were called to go to Arizona to help settle that state. Grandpa and Grandma Eagar moved with them. Grandma Eagar was expecting her first child, and this child, my mother Lucy Lenora Eagar, was born in a covered wagon at Brigham City, near what is now Winslow, Arizona. After the child was born, the family continued to Round Valley and finally settled in what is now known as Eagar, Arizona, so named after my grandfather and his two brothers.

Because Grandma and Grandpa Eagar were such different people, there was much unhappiness in their home. Aunt Sara Eagar Brinkerhoff says Grandpa loved Grandma but thought she should always be at home with the children. He didn’t like to do the things that meant so much to her. He loved to hunt and fish while she liked to sing in the Church choir and every other place where there was an opportunity to sing. She loved to participate in and direct plays and other types of amusements. She also loved to dance. In fact, she loved to be with people, especially the young people, and for many years she worked with them in the Mutual Improvement Association, and this brought her much happiness.

Grandma had a family of seven children. Two of these children died while young, in Eagar, Arizona. Because of the many differences, this marriage ended in divorce. Because Grandma Eagar’s parents lived in Woodruff, Arizona, when the separation came, Grandpa Eagar took Grandma and the children to Woodruff. He bought her a house and a few acres of land so she would have a place to keep a cow and plant a garden. He gave her all he had, but it was not much, and she really struggled to feed her family and supply the necessities of life.

Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar with her mother, daughter, and granddaughter: left to right, Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt (144), Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, Sara Hulda Eagar Brinkerhoff, and Belle Brinkerhoff Shumway. Photo courtesy of Mina S. Evans.

Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar with her mother, daughter, and granddaughter: left to right, Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt (144), Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, Sara Hulda Eagar Brinkerhoff, and Belle Brinkerhoff Shumway. Photo courtesy of Mina S. Evans.

There were few ways a woman could earn money in a small town in those days. Grandma took in washings, and her two oldest daughters helped with this. Many days Grandma and her daughters would stand all day over tub and washboard to earn fifty to seventy-five cents. Also her oldest daughter would help in homes where there was sickness or where they needed her help. She would work from early morning until after dark at night, washing, cleaning, scrubbing floors on her hands and knees, and earn thirty-five or forty cents, or maybe they would give her a piece of worn clothing. These were days of heartache and struggle. Later her second daughter would also go out to work, and made about a dollar and a half a week.

Another thing that later brought in a little money was taking care of the horses that pulled the mail “buckboard.” The mail from the “upper country” was due in Woodruff at four o’clock in the morning, and they changed horses there. The horses had to be fed, watered, and ready to go when the mail arrived. She would always have a warm fire in the fireplace and something warm for the drivers to eat when they arrived, as during the winter they would be almost frozen many times when they arrived. She was poorly paid for this work, but it helped. Still later, she became postmistress in Woodruff, and this helped a little more.

It wasn’t all work. There were plays, dances, parties, Mutuals, and other entertainments in which the family took an active part. Grandma’s passion was music, and she longed to give her children an opportunity to learn something besides work. She saved and schemed and went without until she had saved enough to buy guitars for her two oldest daughters. Aunt Sara says: “No one will ever know the proud joy she took in the girls learning to play those guitars.” She still had a great desire to have an organ in her home. One day Grandpa visited his children and gave her an old note worth forty dollars that a man had owed him for years. He told her if she could collect this money, she could have it. She did collect it and used it to send to Sears Roebuck for a small organ. She had to work and save to get money enough to pay the freight when it arrived, but finally the organ was in her home and uncrated. Aunt Sara says: “She patted it and looked at it with tears running down her face. She could play one chord on it, and before we went to bed she had sung about every song she knew. She never went to bed at all that night.” Her home had always been a place where all of the young people of the town loved to come, and with the new organ, it really became the center of things.

Her oldest son, Sixtus, had inflammatory rheumatism and heart trouble from the time he was eight years old. He died May 8, 1899, when he was seventeen years old. This was a great sorrow to her and to the rest of the family.

Her oldest daughter, Lenora (Nonie), married Franklin H. Owens July 4, 1901, and the second daughter, Sara, married James Brinkerhoff October 5, 1905. This left Lovinia and Leo at home. Grandma was anxious to have them get an education, so she arranged for Lovinia to go to Salt Lake City to study nursing. Then a little later she sold her home and everything she had in Woodruff and moved to Salt Lake City so that her son Leo could go to school. In 1910 she returned to Woodruff. Lovinia also returned and continued to practice her nursing even after she married Eugene Gardner November 11, 1911. Lovinia delivered most of the babies born in Woodruff for many years.

Grandma’s health was very poor, but with help she managed to have a garden, take care of a cow and some chickens, and so managed to get along in this small town. She was not able to get medical attention in Woodruff, so in 1922 her son Leo, who lived in Salt Lake City, came for her and took her to Salt Lake City for treatment. She did not survive an operation to remove a tumor and died July 16, 1922. She was buried in the Wasatch Lawn Cemetery, Salt Lake City, near the place where she was born.

At the time the people of Woodruff dedicated their new church, they collected stories of the people who had lived in Woodruff, and in this book called Our Town and People, a Brief History of Woodruff, Ariz., they had this to say about Grandma Eagar:

Lucy Eagar was a spiritual woman, and a good mixer. She loved to work with people, particularly young people. Many were the plays, parties, and old fashioned socials she sponsored. She had a beautiful singing voice and sang for years in the Woodruff [Ward] choir. Among the many church positions to which she was called was that of president of the Young Women’s Mutual Improvement Association. She gave dignity and honor to that calling for many years. . . . Memories of Lucy Eagar, her beautiful voice, her spirituality, and her enthusiastic leadership remain with those who knew her in life.[4]

Ellis and Boone:

Joel Sixtus Eagar moved back to southern Utah after the divorce and married a widow with four children. They lived in Utah for a few years and then moved to Mexico where he married a third woman and lived in polygamy. His third wife died after giving birth to four children, and his second wife moved back to Utah sometime after the Mormon exodus of 1912 during the Mexican Revolution. In 1920, Joel was living in Cane Beds, Mohave County, Arizona, raising his four children by his third wife.[5] A history of Woodruff lists Joel as one of the early settlers of Woodruff and states, “His children by all three wives numbered nineteen. His children were always a great source of pride and enjoyment to him.”[6]

Lucy Eagar, however, became a permanent resident of Woodruff; she and her daughters became part of the fabric of the town and of the Snowflake Stake. Lucy married Franklin Owens, Sara married James Brinkerhoff, and Lovina married Eugene Gardner. In fact, one of the compilers of the booklet Our Town and People: A Brief History of Woodruff, Ariz. was Lucy’s daughter Sara.

Effie Nan Berry Ellsworth

Unidentified Aunt

Maiden Name: Effie Nan Berry

Birth: November 3, 1906; St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Parents: Herbert Alonzo Berry and Anna May Whiting

Marriage: Ray William Ellsworth; August 11, 1934

Children: Lynn Erwin (1936), Gary William (1941), Elaine Maree (1943), Van LaMar (1946), Evelyn Nan (1947)[7]

Death: January 2, 1948; Alhambra, Los Angeles Co., California

Burial: Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier, Los Angeles Co., California

Effie Berry, the eldest child of Herbert A. Berry and Anna May Whiting, was born November 3, 1906, in St. Johns, Apache County, Arizona. Her grandparents on the Berry side of the family had answered a call by Church authorities to settle St. Johns where they came about the middle of January 1882.[8] When she was a small child, I went to visit them at the Meadows several times, she being my niece. Her other grandparents, Edwin Marion Whiting and Maria Isaacson Whiting, had been called by Church authorities to settle the Meadows, when the “United Order” broke up at Sunset, Arizona. Effie’s parents lived here a short while. I remember what a beautiful child Effie was, the first grandchild on either side of the family. She was a model child and most of her young life they lived in St. Johns.

After finishing high school, she went to college three years and taught school in the Salt River Valley for several years. She also taught in the Los Angeles schools, but then her health interfered. She later took a business course. She served as a clerk in the Arizona Senate, and within a few weeks of being there she seemed to have things in hand and was one of the leaders. After that, she took up radio work, and it looked as if she were going to the top—she wrote scripts and was an announcer. It seemed that she had the gift. Again her health interfered.

Mrs. Isabella Greenway went to Washington, D.C., as congresswoman from the state of Arizona, serving from 1933 through 1936.[9] Effie was her office manager and helped her through a successful campaign. Effie went with her to Washington, D. C., and worked with her the two years Mrs. Greenway was in office. She then took a job with her brother Lee Berry and wife for awhile. She came back to Arizona with a bad case of T.B. (tuberculosis) after serving as secretary to the secretary of the Home Owner’s Loan Association in Washington.

During most of the time when she was accomplishing these things, she was sick; she never had good health. She had been continually told by doctors she would never be able to bear children because her body had failed in some of the functions of motherhood. For this reason she had thought it would not be right to promise marriage to anyone, although she had faith she would have children.

During this time she had serious heart trouble, then came down with T.B. The doctors said her lung would have to be collapsed and she would have to stay in bed a year. It was not much of a success.[10] She told her parents she would like to go to the temple and as they stood in a prayer circle she was healed. She went with a temperature of 103 degrees and she came out without any. They took her back to the doctor and he said, “Well I don’t understand it, but there isn’t any use to treat her; she just doesn’t have it.”

In the meantime, Effie met and married Ray William Ellsworth on the 11th of August 1934. She had three major operations—serious ones—and she had three cesarean operations. Each time the doctors told her she couldn’t live, that it was no use. All through this time, she lived on citrus fruit juices and a little pineapple juice and things of that kind.

Her parents had a letter from the First Presidency stating and telling her what to do. The doctors said she would have to have an abortion and it was agreed that she should have it. But she said first she would like to write the First Presidency of the Church. Their letter said, “Don’t do it, we will get together in the temple on Thursday and offer a special prayer for this girl, by her letter we can see that she is a girl of remarkable faith.” They did that and her child is alive today, as are four others.

Effie Nan Berry. Photo courtesy of Elaine Ward.

Effie Nan Berry. Photo courtesy of Elaine Ward.

Ray William Ellsworth. Photo courtesy of Elaine Ward.

Ray William Ellsworth. Photo courtesy of Elaine Ward.

She had a patriarchal blessing that has guided her through her life. She would read her blessing and say, “No, it cannot be; my blessing says that I will have sons and daughters.” Apostle Spencer Kimball said he believed she had the greatest faith that he had ever known. And our own Patriarch William David Rencher, who to us in our stake is the man we really look up to as being the closest to the Lord, has told me on at least two different occasions, “Of all the people I have ever known, I believe she comes the nearest to having the kind of faith coming closest to the Lord; I believe it is near perfect.”[11]

She had a dream before she was married. A little child took her by the hand and said, “Hello Mama, I’m your little girl.” She had always thought whenever she saw that little girl she would know her. First came the two boys and then a little girl. She said that it was not the one. The doctors said she couldn’t have any more children, but when the last one was born she said to her aunt, “Well this is the one; I know her.” She filled what she thought was the most important part of her mission as she judged life. She probably came just as near as possible to spending each day of her life in the way that would bring her the most [joy, good?].

Her life has been an inspiration to many. She carried the load she had and never complained. She could always see the good side of things and always tried to help others.

Shortly after Effie’s last daughter was born, she did not seem to come back as she usually did but seemed to get weaker and weaker. Her brother Dr. Lee Berry looked after her and spent many nights with her at the last. She passed away January 2, 1948, at Barstow, California. The doctors said in the post mortem that her organs were completely worn out. After such a self-sacrificing life I am sure she will earn a great reward in the hereafter.

A good part of this information was taken from talks given at her funeral.

Ellis and Boone:

A daughter of Effie Berry Ellsworth recently wrote, “Effie (my mother) was not a pioneer. Her grandmother (my great grandmother) Anna Maria Isaacson Whiting was.” Of course, this daughter is correct, but there are interesting pieces of information in this sketch that tell about Arizona in the twentieth century, for example, the time that Effie Berry spent in Washington, D.C., and California. Effie Berry Ellsworth’s life provides a bridge between the pioneer and modern eras.

Isabella Greenway was a long-time friend with Eleanor Roosevelt and campaigned around the state of Arizona for Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. Greenway first ran for Arizona’s sole congressional seat in 1933 when a special election was held as Congressman Lewis Douglas was made FDR’s budget director. Arizona had considered doing without a congressman for one year because of the Depression and expense of a special election but then decided to hold a primary election in August and general election on October 3. Isabella Greenway won both and immediately went to work, even though she was not sworn in until January 1934. She then ran again for the regular election of 1934 and served a little over three years in Congress.[12] From this sketch, it is not clear if Effie Berry worked for Greenway after marrying Ray Ellsworth in 1934.

Catherine Dorcas Overton Emmett

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[13]

Maiden Name: Catherine Dorcas Overton[14]

Birth: June 5, 1823; Martinsburg, Washington Co., Indiana

Parents: Dandridge Overton and Dorcas Wayman

Marriage: Moses Simpson Emmett;[15] August 1, 1844

Children: Emily Dorcas (1846), Eleanor Parthenia (1848), James Simpson (1850), Lovenia Susanne (1852), Thomas Carlos (1855), Caroline Cornelia (1857), Olive Catherine (1859), Moses Mosiah (1862)

Death: December 7, 1905; Fredonia, Coconino Co., Arizona

Burial: Fredonia, Coconino Co., Arizona

So closely connected are the lives of this pioneer woman and her husband, Moses Simpson Emmett, that it would be impossible to tell the story of one without the other.

Moses Simpson, or Simpson Emmett, as he was called, was the only living son of James and Phoebe Simpson Emmett. The parents were of English and Irish descent, and Simpson inherited sterling qualities from each of them. He was born in Kentucky, but it was in Nauvoo, Illinois, that he met and married Catherine D. Overton, of Indiana.

A recital of the hardships this couple and their two small children endured, in the exodus from Illinois and their journey to the West, is almost as miraculous as the famous one of the Israelites from Egypt. They left a comfortable home in Nauvoo, crossed the Mississippi River on the ice, and camped on the Iowa side at a small Indian village called Punkan, near Davenport.[16] The Indians were very friendly to them, vacating one of their wigwams for them, and also, at times, dividing their food with them.

They had taken one step toward the Rocky Mountains; they had been driven from their homes at the point of the bayonet in mid-winter by the hostile state of Illinois. They found friends on the Iowa side and as spring opened, they made all preparations possible and journeyed on westward. At Winter Quarters they were compelled to stop and rest and make some repairs for the onward march. Here they endured some of the most severe hardships that could be. In their crossing the plains, one time food became so scarce in their camp that they were compelled to take portions of a mule which had given out in its travel. No amount of cooking could make this meat tender, but it, and the broth, was eaten by these poor hungry travelers.[17]

One of the Emmett’s two little daughters was but a nursing babe, and during this scarcity of food, the mother had no nurse for her babe, and to add to the agony of her own hunger, she was forced to watch her starving baby grow weaker and weaker until one day, the courage of the camp seemed exhausted and it looked as if they must resign themselves to actual death from starvation out in the midst of a heartless desert where howling wolves would rejoice over their awful fate and glut their snarling selves upon the famished flesh of their hapless victims. At this trying time, their leader went from wagon to wagon for the purpose of comforting and encouraging them, but when he learned fully the sad condition, he shed tears and exclaimed, “How shall I comfort a starving people when I have no bread to give them?” In his heart he pled with the Lord for help; then the spirit of the Lord rested upon him and he prophesied that before they left that camp they should have food in plenty.[18]

In fulfillment of this prophesy the quails came in hundreds, lighting upon the ground among their wagons. All the people gathered quail; they dressed, cooked, and ate until all were satisfied. Even the starving babe ate of the broth, revived, and lived. They renewed their journey with joy and thanksgiving, often singing by the way, or one in jocular mood induced a rousing laugh. Music, dancing and games were often indulged in at night after supper. So on and on, after many weary, happy days, the Emmetts with the rest of their company arrived in Salt Lake Valley where they remained until they, with others, were called to help build up other settlements to the north and south of Salt Lake.

The Emmetts settled at North Ogden where they lived a number of years. The next move was to St. George in the southern part of Utah. Just naturally a frontiersman, Simpson lived in Pinto and then moved to Hamblin, a stock ranch, where his children grew up. There were five girls and three boys in the family.

Simpson Emmett was a born naturalist, a lover of the soil and its products, both plant and animal. His wife was a born nurse and no suffering creature escaped her notice. Together they spent the best part of their lives on the frontier, passing through the trials and hardships which naturally attend the frontier life, and in these experiences they developed great strength and character, believing that anything others had done they too could do. They became very resourceful and were capable of changing their occupation according to the needs in every change of circumstances. Thus instead of being master of but one trade, the Emmetts worked at many kinds of work, mastering several.

Catherine Dorcas Overton Emmett. Photo courtesy of the Church History Library.

Catherine Dorcas Overton Emmett. Photo courtesy of the Church History Library.

They built a comfortable home in Hamblin. This town was named after Jacob Hamblin, one of the very successful Indian missionaries.[19] He was well respected and set before his frontier neighbors an example of thrift and industry. The Emmetts were just simply humble people, reserved and unassuming. Their home in Hamblin was very attractive because of its neat, well-arranged surroundings of flowers, shrubs, and trees. He cultivated a small farm and large garden where might be found in abundance of all healthful fruits and vegetables. His orchard contained as great a variety as could be grown in the new home land, and they picked berry fruit from shrubbery he had transplanted from the native wild. From his blacksmith shop came the sound of honest labor, for Emmett’s shop was the best in the country. Not withstanding his labors as blacksmith and gardener from early morn until late evening, he always found time to help a neighbor who happened to be in need.

His leading characteristic was his love for his fellow men. He fed the hungry, helped the poor, soothed the brokenhearted, and set and bound the broken limb. He was a kind and loving father. He was a friend to man and beast. Men sought after and respected him; animals loved and followed him, and when he kept bees, he worked among them without glove and veil. Even the wild men were tame to him and gathered into his blacksmith shop to have him talk to them, and often their war-bent and wild inclinations were calmed by his gentle talk and persuasion. They found shelter from the storm within his premises and were fed by his hand before departing. They came to him to be named and were very proud when he explained the name he gave them.

Jacob Hamblin, the Indian missionary, was nursed and cared for through eight weeks of severe sickness in the Emmett home, and later, Simpson Emmett was the means of saving Jacob Hamblin’s eldest son, Lyman, from a terrible death.[20] Young Hamblin was riding a wild horse. As he came tearing up the road, the horse threw him. His foot was caught in the stirrup and he was dragged half a mile. As they were nearing a deep rocky gulch a short distance from the house, Simpson Emmett stepped out, raised his hand, and, in the name of the Lord, commanded the horse to stop, which it did. Then father and son went quickly to the horse where he stood trembling; they released the foot, tied the horse to an oak tree near by, then carried the young man across the gulch and into the house where he was nursed back to health. After four days of unconscious stupor, he revived, and in due time became well and strong.

Catherine Emmett was a very capable and dutiful helpmate to her husband and, like him, varied circumstances had made her very resourceful. Her charitable nursing among the sick in those frontier homes was much appreciated among the poor people.

At times when there were no available schools, their children, as well as those of their neighbors, were taught by them in their home. The mother also taught music to her own as well as others. Home amusements were encouraged, the father taking the lead. The older daughters were mostly self-educated, as being on the frontier they did not have the advantage of college. They bought books and studied at home, and when they had finished they took a short course at high school, passed the examinations, received their diplomas, and became successful teachers.

As Southern Utah was great for stock raising, the Emmetts added this and dairying to their industries and, as result of the united efforts of the family in industry and economy, they became prosperous, having a nice home with pleasant surroundings and plenty of all the necessities of life. Simpson Emmett was one who not only looked well after the present but was able to look into the future.

During the prosperity of the Emmett family, the parents continued to teach their children industry and economy. The girls were taught by their mother to mend and care well for all that came into their hands. The mother often said, “My children, we now have plenty, but when you are older, you don’t know what circumstances you may meet but if you care well for all that comes to you, you will be able to meet whatever conditions may come to you. Whatever you have, God gives and it is up to you to make the best of it.” Thus they were taught to nurse the sick, card wool, spin yarn, weave cloth, sew, and knit, and to value the life of all domestic animals; also to enjoy the existence of all plant life, as all these add to the comfort and joy of one’s existence.

Even in their later life, surrounded as they were by every comfort, there were still new frontiers to subdue, and Simpson Emmett’s last move was to Fredonia, Arizona, where with characteristic energy, he made another home, and here he and his faithful helpmate spent the sunset of their long and useful lives and were buried side by side in the land of Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

Catherine Overton Emmett was born in Indiana and followed her husband from Nauvoo, Illinois, to Ogden, Utah, and then to southern Utah and northern Arizona. Although it may not be possible to reconcile all Nauvoo-to-Utah information in this sketch, the general events are impressive. After the death of Joseph Smith in 1844, Brigham Young soon came to realize that the Saints would be moving to avoid further persecution. He began to amass information and make preparations. Leonard Arrington states that James Emmett, Catherine’s father-in-law, was “appointed to explore Oregon and California,” but “without the sanction of the Twelve, [he] left Nauvoo in September 1844 with about one hundred people.”[21] Arrington then noted that this expedition ended in disarray, and Emmett was disfellowshipped. P. T. Reilly suggests that James Emmett started for California in 1849 with his seventeen-year-old daughter, Lucinda, after a family disagreement.[22] Either way (both scenarios may be correct), Moses Simpson Emmett assumed the responsibility of helping his mother and younger sisters as they crossed the plains.

If the information about crossing the Mississippi River on ice is correct, the Emmetts would have left Nauvoo the end of February 1846.[23] It seems unlikely that they then traveled north and east about eighty miles to an Indian village near Davenport, Iowa. Perhaps this instead should be Ponca, Nebraska, where their first daughter, Emily, was born on November 4, 1846. This area is about ninety miles north of Council Bluffs, Iowa, and probably illustrates men traveling both north and south looking for work to support their families. Wallace Stegner mentions Bishop George Miller as spending this first winter with the Poncas near the mouth of the Niobrara River.[24] This seems a likely place and time for living in a wigwam among Native Americans as recorded in the sketch.

Two years later the Emmett family was in Council Bluffs, where their second child, a daughter they named Eleanor, was born on December 17, 1848. This would be the winter of extreme starvation mentioned here with the quail story which is similar to the quails descending on the poor who had fled Nauvoo in September 1846.

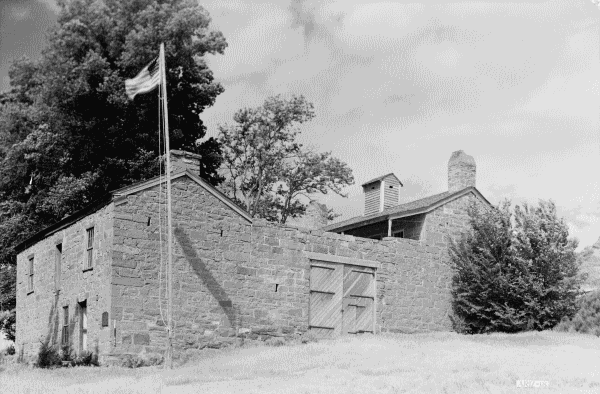

Many members of the Emmett family ran cattle on Arizona Strip land, including the Pipe Springs Ranch. This facility also served as a fort, providing protection to settlers. Pioneers could spend long periods of time here because even the spring was enclosed within the walls. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Many members of the Emmett family ran cattle on Arizona Strip land, including the Pipe Springs Ranch. This facility also served as a fort, providing protection to settlers. Pioneers could spend long periods of time here because even the spring was enclosed within the walls. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

The next event known for the Emmett family is their trek across the plains in 1850 with the Wilford Woodruff Company. This company left Council Bluffs on June 16 with Moses Simpson Emmett; his wife, Catherine; his two little daughters; his mother Phoebe, age 44; and two younger sisters, ages five and one. A little over one month after the journey began, Catherine’s third child, a son named James, was born “on the plains” on July 28. The company reached Utah on October 14, 1850.[25] As noted earlier, the circumstances surrounding the births of Catherine Emmett’s first three children is an impressive example of pioneer fortitude.

After arriving in Utah, the Emmett family first lived in North Ogden and then moved to southern Utah and northern Arizona. In 1870, Moses Emmett married a second wife, Electa Jane Westover, who was then only eighteen years old. They had no children. Historian P. T. Reilly was critical of Electa’s status in the family, but a granddaughter, Gladys Emmett, had a kinder interpretation.[26] She wrote, “As Cathern Dorcas grew older, Electa cared for her faithfully until she passed away. With the same dutiful tenderness she cared for Moses Simpson until his passing a year following his first wife’s death.”[27] Electa Emmett then moved to St. George where she worked in the temple. She died in St. George in 1925.

This is the only sketch that Clayton collected from extreme northwestern Arizona, or the Arizona Strip as it is generally called, and this sketch was not included in PWA. If this was a conscious decision, it may have been because Catherine lived only in Fredonia. Also, Clayton may have recognized that much of this information was really about Simpson Emmett rather than Catherine. However, with the exception of some of the sketches written by DUP members, this emphasis on the man and not the woman is the norm for pioneer histories in Arizona.[28] At a DUP convention on May 16, 1949, Clayton advised the women against writing joint histories of parents or grandparents. She wanted DUP ladies to “give mother her just dues—tell her history—all of it,” and then said that “unless we tell all the things she did we just can’t do her justice.”[29]

Pioneer Deaths: Emma (left) and Lillian Hall. Many pioneer women buried children as babies or as teenagers. One of these was Emma Matilda Rogers Hall (daughter of Eliza Snow Smith Rogers, 595). Emma married William Hall (son of Henrietta Pearce Hall Steers Minnerly, 469) in 1898, and Lillian was born the next year. The family lived in Mexico for ten years (1901-11), and when they returned, they spent the summers at Los Burros (east of Lakeside) in Apache County, where William worked for the Forest Service. In 1918, three local young men came to take the oldest daughters to a dance in Pinetop. They planned to dance through the night and then have breakfast before returning home. At 3 a.m., when everyone stopped to rest and get a drink, Lillian fainted. The young men took her to a nearby home and sent a message to the family, but she died the next day without ever regaining consciousness. William Hall lamented that he would not be able to hear her beautiful voice again. Photo courtesy of Ralph Lancaster.

Pioneer Deaths: Emma (left) and Lillian Hall. Many pioneer women buried children as babies or as teenagers. One of these was Emma Matilda Rogers Hall (daughter of Eliza Snow Smith Rogers, 595). Emma married William Hall (son of Henrietta Pearce Hall Steers Minnerly, 469) in 1898, and Lillian was born the next year. The family lived in Mexico for ten years (1901-11), and when they returned, they spent the summers at Los Burros (east of Lakeside) in Apache County, where William worked for the Forest Service. In 1918, three local young men came to take the oldest daughters to a dance in Pinetop. They planned to dance through the night and then have breakfast before returning home. At 3 a.m., when everyone stopped to rest and get a drink, Lillian fainted. The young men took her to a nearby home and sent a message to the family, but she died the next day without ever regaining consciousness. William Hall lamented that he would not be able to hear her beautiful voice again. Photo courtesy of Ralph Lancaster.

Notes

[1] A. A. DeWitt, “Abel Alexander DeWitt, Sr.,” in Clayton, PMA, 121−24.

[2] Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt, 144.

[3] “History of Joel Sixtus Eagar,” in Clayton, PMA, 125−27. His middle name is spelled both “Sixtus” and “Sextus.”

[4] Brinkerhoff and Brewer, Our Town and People, 39.

[5] Census records: Nancy Eagar, Hurricane, Washington Co., Utah (1920 and 1940); Joel Eagar, Cane Beds, Mohave Co., Arizona (1920), Holbrook, Navajo Co., Arizona (1930), and Navajo Co., Arizona (1940). Joel Sixtus Eagar died in Hurricane, Utah, in 1947.

[6] Brinkerhoff and Brewer, Our Town and People, 33.

[7] 1940 census, Ray W. Ellsworth, Los Angeles, Los Angeles Co., California.

[8] See Sarah Roundy Berry, 53.

[9] See comments from Ellis and Boone.

[10] Collapsing one lung (to give it rest) was a standard treatment for tuberculosis—and seldom had good success.

[11] William David Rencher (1863–1958) was born in Utah, married Georgeanna Bathsheba Smith, a daughter of Jesse N. Smith and Augusta Outzen (657), and died in St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona. “William David Rencher,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:597.

[12] Miller, Isabella Greenway, 185–233.

[13] If RFC had the sketch for Moses Emmett (as published in PMA) as early as the 1930s, she may have used it as the basis for this sketch. The authorship for that sketch is listed as: “Compiled by Gladys Emmett, granddaughter; Compiled from the writings of Olive Catherine Moffett, daughter, and Florence O. Allred Emmett, daughter-in-law of Moses Simpson Emmett.” Catherine Overton Emmett had been dead nearly thirty years when RFC wrote and submitted this sketch to the FWP. Clayton, PMA, 128.

[14] Clayton spelled the name, Cathern; today it is generally, but not always, spelled Catherine. Also, the last name is sometimes spelled with only one t but usually two; Clayton used both in the FWP sketch. Catherine’s son, James S. Emett, operated Lee’s Ferry for a number of years and, in contrast to his parents, generally spelled his name with one m. For more on the Emmett family, especially James, see Reilly, Lee’s Ferry, 145−79, 204, passim.

[15] Gladys Emmett, “Life Sketch of Moses Simpson Emmett,” Clayton, PMA, 128−32.

[16] This location may be incorrect as Davenport is about 80 miles northeast of Nauvoo. See comments by Ellis and Boone.

[17] The Emmett family traveled to Utah with the Wilford Woodruff Company of 1850. MPOT.

[18] Generally, the “miracle of the quails” is associated with the “poor camp” before they reached Winter Quarters. Allen and Leonard wrote, “Approximately 640 destitute Latter-day Saints were forced to cross the river in September [1846]. They crowded into makeshift tents on the river bottoms, where many contracted chills and fever in the cold September rains. Word of the condition of the ‘poor camp’ reached the Twelve, and a relief company was sent with provisions, tents, and wagons. On October 9, still practically destitute, the ‘poor camp’ organized for the journey west. On that day flocks of quail, exhausted from a long flight, settled for forty miles along the bottom lands. The hungry Saints easily and gratefully caught them with their hands. Food had been provided when it was badly needed.” Allen and Leonard, Story of the Latter-day Saints, 222.

[19] Jacob Vernon Hamblin (1819–86) was an LDS missionary to the Navajos and early explorer and settler of northern Arizona. He died at Pleasanton, New Mexico, but is buried at Alpine, Arizona. “Jacob Hamblin,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:100–1. For a history of one of his wives, see Louisa Bonelli Hamblin, 234.

[20] Lyman Hamblin (1847–1923) was the oldest surviving son of Jacob and Lucinda Taylor Hamblin. Lyman was an early settler of Apache County and died at Eagar. AzDC.

[21] Arrington, Brigham Young, 121–22.

[22] Reilly, Lee’s Ferry, 145.

[23] Arrington states, “On February 24, the temperature dropped to twelve degrees below zero, freezing over the Mississippi and permitting great caravans to cross on the ice.” Arrington, Brigham Young, 127.

[24] Stegner, Gathering of Zion, 45.

[25] Spending four years in Iowa getting ready to cross the plains was not uncommon. MPOT.

[26] Reilly, Lee’s Ferry, 145.

[27] Moses Simpson Emmett died April 5, 1907. Gladys Emmett, “Life Sketch of Moses Simpson Emmett,” Clayton, PMA, 131.

[28] For another example, see Susanna Hammond Deans, 135.

[29] County Convention, DUP minutes, May 16, 1949, Mesa Historical Museum.