D

Rita Curtis Lee, "D," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 129-158.

Adeline Grover Daley

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Adeline Grover

Birth: February 17, 1835; Freedom, Cattaraugus Co., New York

Parents: Thomas Grover and Caroline Whiting

Marriage: Phineas Marion Daley; January 27, 1853

Children: Phineas Marion (1853), Adeline E. (1857), Seretta Ann (1859),[1] Eugene (1861), Ornetus Alonzo (1863), Emma (1873)

Death: April 19, 1919;[2] Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Adeline Grover was the fourth daughter of Thomas Grover and Caroline Whiting. She was born in Freedom, Cattaraugus County, New York, February 17, 1835. The following list of children blessed the union of Thomas and Caroline: Jane, Emeline, Mary Elizabeth, Adeline, Caroline, Eliza Ann, and Emma Grover.

Adeline Grover Daley. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Adeline Grover Daley. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Thomas and Caroline Grover were known to have resided in Freedom until after they had received the restored gospel and joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and decided to join with the Saints that had settled Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois.[3] Before they were forced to vacate this beautiful city, Caroline became seriously ill and passed away. She is buried in Nauvoo, their city of refuge.

Thomas Grover was ordained a member of the High Council, serving with honor and distinction. He loved his friend and prophet, Joseph Smith, and to the extent that he could, he was willing to do anything that was required of him to further the establishment of the Church and kingdom of God here in the earth. Thomas was among a group of Saints who had gathered near the jail in Carthage, Illinois on that fateful day when Joseph and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were murdered. It was Thomas Grover who daringly stepped forward and in a loud voice proclaimed, “I am not afraid to claim our prophet’s body.” He quickly strode to where Joseph had fallen from the window when he was shot and was lying propped against the side of a well. Thomas tenderly gathered the shattered and lifeless form into his strong arms and carried it to a wagon where he placed it upon a bed of clean straw. Others had held back, fearing to be shot by the howling mob that had them greatly outnumbered.[4] Thomas Grover passed away February 20, 1886, in Farmington, Utah after living a long, useful life.

Adeline Grover was of this same strong, sturdy stock. She too, braved hardships for the sake of the gospel and her family. She was only twelve years of age when her father, his families, and others fled Nauvoo and walked with the handcart company across the plains, arriving in Salt Lake City in the fall of 1847.[5] Only the brave and the strong could survive the bitter cold, thawing ground, and spring rains. Many died of exposure, thirst, and weariness. It was a glorious occasion for those who lived to greet friends and relatives in their “promised land.”

Note: While researching the original edition, we found that much of the information about Adelaide’s time in San Bernardino, California, was incorrect. Therefore, we deleted two paragraphs and substituted the following information in brackets.

Adeline Grover Daley (right) with her sister, Mary Elizabeth Grover Robinson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Adeline Grover Daley (right) with her sister, Mary Elizabeth Grover Robinson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

[When Thomas Grover brought his families to Utah, Adeline’s older sister Emeline had already married Charles C. Rich as his fifth wife. In 1851, Rich led a company of Utah pioneers to settle at San Bernardino, California, and took three of his wives, including Emeline. It may be that Adeline accompanied her sister. In California, Adeline met Phineas Daley, son of Moses Daley and Almira Barber, and married him in 1853.

In 1857, President Brigham Young called for the Saints in far away places to sell their land and move nearer to Church headquarters. Not all members in San Bernardino chose to move. George Warren Sirrine and Charles Crismon immediately returned to Utah, but Phineas and Adeline Daley continued to live in San Bernardino until after the 1870 census. Adeline’s last child, Emma, was born in Idaho in 1873.

In January 1877, Adeline’s daughter, Seretta, married Warren LeRoy Sirrine (see 649), and that fall the Sirrine and Crismon families were on their way to Arizona. The Daley family did not go south until later. In 1880, Phineas was living with his second wife in Payson, Utah, and Adeline was living with her children in Paris, Idaho. When the Daleys decided to moved to Arizona, Phineas’s second wife chose to get a divorce and stay in Utah, but all of Phineas and Adeline’s children moved south. Mesa became the permanent home for all but Eugene.]

Fairy Queen's Float, Pioneer Jubilee parade, Salt Lake City, Utah July 1987; B. L. Singley, photographer, Keystone View Company. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Fairy Queen's Float, Pioneer Jubilee parade, Salt Lake City, Utah July 1987; B. L. Singley, photographer, Keystone View Company. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Adeline Daley was strong in her faith—persevering in all things and not easily discouraged. She willingly shared with others less fortunate and was known to be a good neighbor. Phineas and Adeline had reared a fine family who were respected in the community. Their sons and daughters are the following: Phineas Marion, Adeline, Serretta Ann, Eugene, Orneitus Alonzo, and Emma Daley. They, in turn, have had fairly large families resulting in a large posterity. Grandmother [Adeline] Daley was an immaculate housekeeper; she was very neat in her personal appearance although rather large of stature. She was independent and self-sustaining, managing well without her husband who chose in their later years to live with their son Eugene and his family residing in New Mexico. Adeline loved to share her small but neat home located on the northwest corner of East First Street and North Sirrine, across the street from her daughter Seretta Sirrine and family. The Sirrine granddaughters, Maude, Esther Ann, and Ethel, were thrilled to take turns spending the night with their beloved grandmother. Esther proudly recalls many trips to the store when she took butter and eggs to be exchanged for groceries and being rewarded with some special goody for her effort.

Adeline Grover Daley was invited to attend the 50th Pioneer Jubilee held in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1897.[6] Her daughter Addie and husband, George Passey, owners of a local clothing store outfitted Mother Daley in the finest attire to make the trip. Adeline was awarded a beautiful brooch commemorating this occasion, which she proudly wore throughout the remainder of her life.[7] She passed away in her home in April 1919 at the ripe old age of eighty-five years and is buried beside her husband in the Mesa Cemetery. She was truly one of our NOBLE PIONEERS!

Ellis and Boone:

Adeline Grover Daley lived in New York, Illinois, Utah, California, and Idaho before coming to Arizona. In 1897, Utah’s Semi-Centennial Commission put together a spectacular celebration to honor the 1847 entrance of pioneer companies into Utah. Only one year after Utah was admitted as a state, this four-day celebration overshadowed all previous events in Utah. The pioneers used flags, eagles, seagulls, and beehives as symbols important to Utah citizens. The Deseret Evening News announced, “Salt Lake City has perhaps never before been so packed with enthusiastic sightseers. The streets cease to be streets about the time when parade begins—they are rivers of humanity in which the people surge to and fro, here moving rapidly for a stretch in ripples of anticipation toward some happening a block or two away, there forming a whirlpool which moves round and round some striking object of interest.”[8] As illustrated by Adeline Daley’s trip, Mormon pioneers from throughout the Mountain West came to celebrate.

Ann Casbourne Williams Dalton

Author Unknown, FWP

Maiden Name: Ann Casbourne

Birth: December 27, 1832; Southery, Norfolk, England

Parents: Abraham Casbourne and Susanna Ward[9]

Marriage 1: Charles David Williams;[10] February 14, 1855

Children: Ann Susanna (1855)

Marriage 2: John Dalton Jr.; August 23, 1856

Children: Margaret (1857), Mary Ann (1859), Jemima (1861), Marium[11] (1864), David (1868) Ellen Letitia (1872)

Death: August 25, 1925; Chandler, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Probably the tiniest of Arizona’s pioneer women was “Little Grandma Dalton,” whose height was four feet six inches and who never weighed more than eighty pounds, while at the close of her almost ninety-four years of life her weight dwindled to half that amount.

Born in Southery, Norfolk, England, December 27, 1832, Ann was the daughter of Abraham and Susannah Ward Casbourne. At the age of ten [eighteen] she came to America with her parents. While at sea they encountered a terrific storm that lasted twenty-four hours, during which their vessel, the Hibarnium, was rammed and a large hole made in her side by a merchant ship.[12] The vessel was badly disabled but through the courageous effort of the noble captain and brave crew, the Hibarnium, with all her passengers, was saved, while the other ship went down with all on board. After landing safely in New York harbor, the Casbourne family continued their journey to St. Louis where Ann’s two eldest brothers had gone several years previously and had sent to England sufficient funds to emigrate the remainder of the family.

They did not profess any religion, and although good honest people, they were not what is called a religious family. During the latter part of the summer, after their arrival at St. Louis, the father became very ill from working in a brick yard in the excessive heat. He finally became so ill that he asked for one of the men that he had been working with, a Mr. Jones, to come and pray for him. He understood that Mr. Jones was a religious man although he did not know to what sect Mr. Jones belonged. Mr. Jones came and when the prayer was ended the sick man turned to his daughter Ann and said, “This man believes in the true church of Christ. Live an honest upright life, for there is a great work for you to do.” This greatly impressed the young girl and was an inspiration to her all her life. She diligently tried to live up to the counsel of her dying father. He departed this life in the month of August 1850. This was a great trial to the family as they were almost strangers in a strange land and without a home.

They soon moved to the outskirts of the city, where they rented some rooms of a lady whom they soon discovered was of the same faith as Mr. Jones, namely, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They soon became acquainted with quite a number of persons that belonged to this denomination. One Sabbath, Ann, with her mother, attended one of their meetings and listened to a discourse delivered by Elder Orson Pratt on the principles of the gospel. Ann was converted to the new faith and was baptized the next day.[13] She was a faithful member of the Church and active to the last, a strong advocate of the gospel of Jesus Christ. She was the only one of her father’s family to join the Church.

Ann Casbourne Dalton. Photo courtesy of Dixie Krauss; Krauss, Perry and Lora, 182.

Ann Casbourne Dalton. Photo courtesy of Dixie Krauss; Krauss, Perry and Lora, 182.

For two years after her father’s death, Ann worked very hard to help support her family. She then had a desire to get to Zion. Her mother consented to her daughter joining the Church if she felt disposed, but could hardly endure the thought of her leaving her home and going so far away to live among a strange and unpopular people.

But in April 1854, she left all who were so dear to her and came to Utah in the company of Captain William Empey. While crossing the plains, she cooked and washed for the Church teamsters to pay her way out. Among the teamsters was a praiseworthy young man by the name of David Williams, who sought and won her promise of marriage when they should reach their destination.[14]

They arrived in Salt Lake City, October 24, 1854, after having a pleasant journey of so many hundred miles. Ann made her home with Brother Empey until February 14, 1855, when she was married to David Williams. For seven short months, they enjoyed perfect happiness. Then her husband went to work in a saw mill in Big Cottonwood for a Mr. Davis. David Williams acted as sawyer, and in some unaccountable way he was thrown across the saw and killed in September 1855. On November 19, 1855 Ann gave birth to a baby girl, Ann Susanna Williams.

In time, Ann went to work in the family of Brother John Dalton at the Church farm in Sugarhouse Ward. While there she had many manifestations of the power of the Lord. During the grasshopper raid when food was extremely scarce, President Young told Bro. Dalton never to turn anyone away hungry and he would never want for flour. This promise was literally fulfilled many times. When Ann would go to the flour bin, she would take every bit of flour wondering where the next was coming from. She would bake it into bread, dividing with any who came their way. When this was gone, she again went to the bin and there was still a little flour. Again she scraped the bin clean, but every time she needed to make bread there would be sufficient flour in the bin. This continued for some time, until flour was more plentiful and they were able to purchase some.

Ann was married to John Dalton August 23, 1856, entering the law of plural marriage where she continued to help all she could in the family. Ann took part in the great move when Johnston’s army was sent to exterminate the Mormons.

After this, her husband was called to settle Southern Dixie. After moving south she suffered many trials and privations. For a while they lived in Virgin, and then moved to Rockville. While at the latter place, Ann had a numb palsy stroke and for three months she was perfectly helpless. By her request, she was carried to ward conference and there had the power of the priesthood exercised in her behalf, and she was instantly healed. She then went to the St. George Temple and did work for her dead ancestors. When she returned home, she was able to do her work, although her fingers and toes were drawn and doubled up from want of proper care and attention during the time she was helpless. This prevented her from doing many kinds of work, but she kept on working, doing every thing her poor crooked hands could do, because she had to earn a living for herself and her children, with what help her children could give her.

In 1880, Ann moved to Arizona in company with Jacob and Charles Brewer and their families.[15] Charles Brewer was her son-in-law, having married the little girl, Ann Susanna, that was born so soon after her father’s death. For a number of years, Grandma Dalton lived in Taylor, Arizona, and then moved to Pinedale. At both places she was active in Relief Society, Sunday School, and Primary. She was also postmistress at Pinedale for some years, running a little store in connection with it.

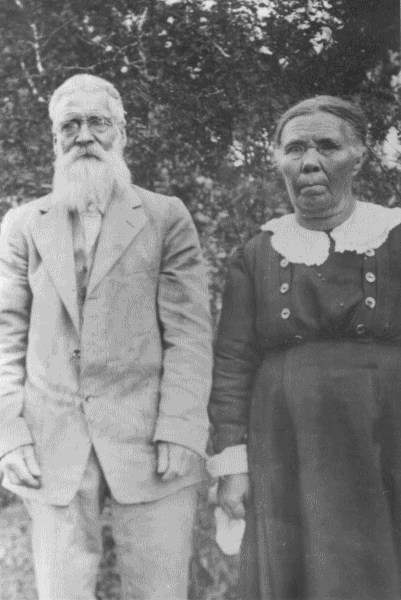

Ann Casbourne Dalton with children; front (left to right), Mary Ann, Ann Casbourne, Jemima; back, Marium, David, and Ellen Dalton. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 183.

Ann Casbourne Dalton with children; front (left to right), Mary Ann, Ann Casbourne, Jemima; back, Marium, David, and Ellen Dalton. Photo courtesy of Krauss, Perry and Lora, 183.

During the later years of Ann’s life, her summers were spent in the mountains of Navajo County, but when the cold weather arrived, she sought the warmer clime and stayed with her children in the Salt River Valley.

“Grandma Dalton,” as she was lovingly called by all who knew her, had a large circle of friends, especially among the children to all of whom she had something pleasant to say. She was the mother of six daughters and one son, and at the time of her death she had over 300 living descendants.

Ann Casbourne Dalton died August 25, 1925, at the home of her daughter Mrs. Mary Ann Smith, on the Huber Ranch in Chandler. Four daughters and one son were living at the time of her death. She was buried August 28, 1925, in Mesa, Arizona. Although small in stature, Ann Casbourne Dalton was a giant in courage, cheerfulness and endurance.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch was originally submitted to the FWP in 1936, and then it was reworked for PWA. Without knowing why changes were made (if they were typographical errors, changed at the request of a descendant, or changed through the whim of RFC or her typist), further research is warranted. For example, the FWP sketch states that Ann Casbourne came to the United States at age eighteen and PWA lists this age as ten; both of these ages are written in numerals so a typographical error is possible.

Nevertheless, it seems obvious that at least the substantial changes were included on purpose and probably came from a descendant. These additions were mainly information associated with membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For example, PWA gives the story of her conversion rather than just the fact, the faith-promoting story about the flour bin is added, and mention is made that her marriage to Dalton was a plural marriage and that they temporarily moved south because of Johnston’s army. Two other items were apparently corrections. The FWP sketch calls her a widow of John Dalton when she came to Arizona, but he was still alive when she left Utah. Also in the FWP sketch, the story about the palsy was placed before her marriage to Dalton, but PWA places this later while they were living at Virgin and adds the information about the St. George Temple.

Finally, these two paragraphs were not transferred from the FWP sketch to PWA. They are added here because they provide a bit of color to the life of Ann Casbourne Williams Dalton.

“Always cheerful and happy in spite of affliction, she attended many of the pioneer picnics in the Salt River Valley and was crowned ‘queen’ on four different occasions. At a celebration July 4, 1908, she creditably rendered a part and even step danced, much to the delight of all though she was past 76 years of age.[16]

“Active until within six months of her death she was given a beautiful funeral service and interred in the Mesa Cemetery, six of her grand-daughters serving as pall bearers.”[17]

Susanna Hammond Deans

Rita Curtis Lee[18]

Maiden Name: Susanna Hammond

Birth: January 10, 1850; Little Cottonwood, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Parents: Joseph Hammond and Elizabeth Egbert

Marriage: James Deans; May 16, 1868

Children: James Hammond (1869), Helen Lovisa (1871), Elizabeth Emily (1874), Joseph Hammond (1876), David Woodruff (1879), Susanna Euphamie (1881), Robert Alexander (1884), Archibald Haswell (1887) and Isabelle Irene (1889)

Death: May 19, 1936; St. George, Washington Co., Utah

Burial: St. George, Washington Co., Utah

James Deans was born February 14, 1844, at West Houses, Edinburgh, Scotland, the first child of David Deans who was born in Scotland and Helen Haswell, who was born March 25, 1825, also in Scotland. Both Helen and David were, in their native country, good hard-working, honest people.

They were converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Edinburgh, Scotland. David and his wife had planned to come to America with their two small children, James and Isabelle. But on July 14, 1848, just a short while before they were to leave, David Deans was killed in a coal mine accident where he worked. The mother, broken hearted but determined, made the long trip across the ocean to America with her two small children, and in the company of her husband’s brother. Upon arrival, the brother stayed in St. Louis, and Helen Deans came on alone and made her home in St. George, Utah.

Hammond siblings, left to right: Robert Hammond, Susanna Hammond Deans, John Egbert Hammond. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Hammond siblings, left to right: Robert Hammond, Susanna Hammond Deans, John Egbert Hammond. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Some time after settling in St. George, Helen met and married a man by the name of Archibald McNeil. [Eight] children, [seven] boys, and one girl were born to them. Their names are David [born 1854], John [1856], Archibald [Haswell 1858], William [Haswell 1863], [Andrew 1860], Frank [Peter Francis 1865], George [1869], and [Helen] Euphamia [1866].[19] Some of these children later settled in Nevada, but no more information is available at this time on them. James and his sister Isabelle were reared in St. George along with their step-brothers and sister.[20]

Helen Haswell Deans [McNeil] passed away August 8, 1907, at St. George, Utah. David Deans’ great-granddaughter, Emily J. Manning, has a birth date for David Deans, it being March 1824 in Scotland.

Susanna Hammond was born January 10, 1850, at Little Cottonwood, Salt Lake City, Utah. She was the fourth child of Joseph Hammond, who was born June 14, 1822, at Moline, Franklin County, New York, and Elizabeth Egbert, who was born March 22, 1824, in Sullivan County, Indiana.

Her father and mother were staunch members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and her father was a body guard to the Prophet Joseph Smith during the early trials of the Church. When the Saints were driven out of the east, Joseph and Elizabeth, along with their three older children, came to Utah with the Brigham Young Company.[21]

Susanna’s father was called by the President of the Church to help settle St. George, in Washington County, Utah. And she, along with her parents, was with the first company of Saints to arrive in October 1861. The first winter there, they lived in their wagon and a willow wigwam. During her girlhood, she experienced the regular hard trials of the southern Utah pioneers. Her father, Joseph, died August 31, 1899, at St. George, Utah. (Note: Above dates taken from family records. Life sketch of Joseph Hammond states he died August 4, 1899.)

In the small community of St. George, everyone was acquainted, and in due course of time as their childhood dwindled and they became young adults, James Deans and Susanna Hammond fell in love and were married May 16, 1866 or 1867, in the old Endowment House in Salt Lake City, Utah. Susanna was seventeen years old and her husband was twenty-two.

Susanna gathered cotton from the fields, spun it into thread, and then wove it into cloth for her own wedding dress, sheets, and quilts. She was very adept with her hands, especially with sewing, and up until a short time before her death, she still saved bright scraps of cloth and made them into lovely quilts. When they were married, they had only two tin plates, two tin cups, and each had an iron-handled fork, knife, and spoon with which to start housekeeping.

Nine children were born of this union. They were James Hammond, born April 18, 1869; Helen Lovisa, born November 11, 1871; Elizabeth Emily, born January 14, 1874; Joseph Hammond, born October 22, 1876; David Woodruff, born February 25, 1879; Susanna Euphamie, born October 29, 1881; Robert Alexander, born October 28, 1884; Archibald Haswell, born May 28, 1887; and Isabelle Irene, born September 7, 1889. They all lived to adulthood but Archibald Haswell. He passed away when he was a child.[22]

In 1877 or 1878 James and Susanna, along with their first four children, James, Nellie, Bessie and Joseph, were called by President Brigham Young to help settle the country at Woodruff, Arizona; all the other children were born and raised here.

James was the first Justice of the Peace in Woodruff, Arizona, and was also clerk in the United Order under which the Saints were living at that time. One of his children, David Woodruff, was named after President Wilford Woodruff, as he was the second child born in the United Order. James and Susanna and their children lived in the old fort built in Woodruff for ten years before they moved into a house.

James was by trade a wonderful gardener. When there was enough water to use, he always had a very large garden, which contained several rows of flowers along with melons, popcorn, vegetables, and fruit. He would haul his vegetables and produce to Holbrook, which was twelve miles from Woodruff, and sell them for clothes and groceries, and always he remembered a little bit of candy for the children. James’s family never wanted for food, but clothing in those days was not so easy to come by. The children had to go barefooted in the summertime.

James Deans was also among those who built the dam across the Little Colorado River, which furnished the water for the farms and gardens. The dam was put in much the same way as a stop is put in a canal.[23] Many nights James, with other men of the community, walked the banks all night long watching to see if the dam would hold, but it did not and with it went the hopes of the people for crops for several years. They would have to haul water in, with the women and children helping to keep the watch in the daytime. There was plenty of fruit and vegetables, grain, corn, and etc. to live on.

The last time the dam went out was in 1891. James took his wife and three younger children, Isabelle, Robert, and Susanna, (the youngest son Archibald having passed away). They went to St. George to stock up on supplies to last them through the winter and until the dam could be put in again. They were there several weeks before they were ready to return to Woodruff. The family that came with them decided to stay in St. George all winter, but James had to return as he was overseer for the men who worked on the dam, and also the rest of the family left behind would soon be out of food.

One incident happened on the return trip, which was very frightening. They had to cross the desert, which was a long ways between water holes. One night James drove all night and every little while he would wake up the children and give them a swallow of water out of a canteen that he had. The next morning they finally reached water, for which they were extremely thankful, for if something had happened to their wagon or one of the horses, they would have surely perished on the desert.

Canning of fruits and vegetables was unknown at that time, so most of the food raised for storage was dried corn, beans, and peas. Also fruits were dried, such as peaches, apples, pears, and etc., for winter use.

On account of the Indians, the settlers built their homes close together in a small village and had their farms outside of town. Sometimes when the Apache Indians would get off their reservations, the soldiers would bring them back through the town; the women and children would run into their houses and not come out until the soldiers had gone through. It was a frightening experience, and the children would mostly hide under the beds.

After they had lived in Woodruff for many years, President Wilford Woodruff came down and released James and the others that had been called to settle there from their missions. President Woodruff placed his hands on James Deans’s head and blessed him as he told him that the Lord had many blessings in store for him and his descendants.

Not long after that they made plans to move back to Utah. They had hoped to take up a home on the Ute Reservation, which was being thrown open for white settlers, but because they didn’t draw a right number, they didn’t get a chance for any land, so they bought the little home they lived in. It was in a part of Fourth Ward, now known as Glines Ward.[24] It was owned by Al Wardle when they bought it. And is now owned by Mrs. Loraine Deans, wife of David W. Deans, son of James Deans.

Neither James nor Susanna had the advantage of regular schooling, but both were good readers and writers. James had a lovely singing voice, and he used to hold his children on his knee and sing Scottish songs to them; one of their favorites was “Annie Laurie.” He would read all the newspapers and books he could get hold of and also helped the children with their school lessons.

James helped to quarry the rock used in building the St. George Temple and Tabernacle. Susanna supplemented their meals by gathering sego lily bulbs and wild onions. She also ground corn in a coffee mill to make bread.

Christmas was a wonderful time at the Deanses’ home, and James liked to have it remembered as the holiday was celebrated in Scotland. The children hung their stockings on the fireplace, and there was always something left in each one to make that particular child happy.

Susanna was a person of few words and seldom let people know how she felt, but one of her unhappy experiences was the first Christmas they were in the Uintah Basin when they had nothing to put in their children’s stockings. Nor was there anything for Santa to leave by their beds either.

In the fall of 1897 while James Sr. and Susanna were living in Vernal, they, with their oldest son, James Hammond Deans, Robert, and Isabelle, went to St. George where their son Jim was to go through the temple for his health. He had been ill for several years, having had a stroke which left him partially paralyzed. They arrived in St. George in October and were only there a few days when James Jr. took ill and passed away on October 26, 1897, at the age of twenty-eight. He was buried in St. George without being able to go through the temple.

They had to travel by team and wagon and were returning home by way of Orangeville, Utah, where a brother of James Sr. lived. He, James Sr., became ill with pneumonia and died December 23, 1897, and was buried there Christmas Eve.[25] So it was a very sad Christmas for the family that year. A son, Joseph Deans, and a son-in-law, Samuel Johnstun, took a team and wagon and went to Orangeville and brought Susanna and her two children back to Vernal. There’s where she remained and raised her family to adulthood.

In the fall of 1919 she and her youngest daughter, Isabelle, went to Mesa, Arizona, to spend the winter with another daughter, Bessie Johnstun, and family. When spring came, Susanna and Isabelle started back to Vernal and got as far as St. George. They stopped to visit relatives. When Isabelle met and married Vern Fullerton, there they made their home.

Susanna passed away in May 1936 and was buried there beside her oldest son, James Hammond Deans.[26]

Ellis and Boone:

Although Susanna Hammond Deans and her husband did not permanently remain in Arizona, they were particularly influential in the settlement of Woodruff. Charles S. Peterson wrote, “After the loss of dam number one in 1878, only three families remained—those of L. H. Hatch, James Dean[s], and Hans Guldbrandsen. Interestingly, these, along with the families of James C. Owens, who came in 1879, L. M. Savage, and one or two other latecomers, became the stable element in the town’s population. It became the role of these people to recruit others.”[27]

Achsah May Hatch Decker

Unidentified Offspring, FWP[28]

Maiden Name: Achsah May Hatch

Birth: August 29, 1875; Franklin, Franklin Co., Idaho

Parents: Lorenzo Hill Hatch[29] and Catherine Karren

Marriage: Louis Addison Decker; [30] October 8, 1897

Children: Louis Francis (1898), Catherine (1901), Lorenzo Bruyn (1903), Alma Virgil (1904), Don Zachariah (1906), Jesse Smith (c. 1908), Joy Wesley (1911), Carl Hatch (1913), Glenaveve (1915), Freda Seraphine (1916)

Death: September 3, 1964; Provo, Utah Co., Utah

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Achsah May Hatch was born August 29, 1875, at Franklin, Idaho, the daughter of Lorenzo Hill and Catherine Karren Hatch. She came of a long line of Vermont Hatches and at least one English Ratcliff who jumped out of a two-story building in order to marry the man she loved. Her parents were among the first Arizona pioneers. In fact, at the early age of three months, Achsah May found herself a completely initiated and active pioneer.

In the same year that she was born, December 1875, when Achsah May was about four months old, they emigrated to St. George for a year. But in those days, the homes of the pioneers were in many cases merely temporary places of abode, and in July 1876, Achsah May’s father was called to New Mexico on a mission to the Indians. He went willingly because he knew that he could only find true success in doing what he was told to do.

Louis and May Hatch Decker, c. 1948. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Louis and May Hatch Decker, c. 1948. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

While in New Mexico, Achsah May became the favorite of a handsome and rich caballero. Under his tutelage and with his valiant efforts, at the age of eighteen months, Achsah May began her career as a señorita and learned a scramble of the Spanish language.[31] She distinctly remembers calling for agua. Incidentally, agua is about the only Spanish word Achsah May speaks fluently today.

In March 1878, her father received a call to come to Arizona as a missionary and pioneer to help establish colonies, build the bridges, and kill the snakes, in general to subdue the country. His wife Catherine and her children came with him. They settled in Woodruff, where they lived in the United Order. Her mother took her turn in the “big kitchen” along with the rest of the women. While living in the order, Achsah May attained a good deal of notoriety, caused chiefly by her loud wailing for Joe Deans’s blue willow plate. Ever since this stage of her life, Achsah May has retained an aesthetic desire for beautiful china.

For the next seven years, the Hatches lived in Woodruff. Here Achsah May spent the usual gay hours of childhood. She made many very dear friends by a winning personality and a vivacious interest, not only in life itself, but in the artistic and beautiful things that make life more than merely a drab existence.

Then the family moved back to Franklin, Idaho, where Achsah May lived until 1892. Then they came back to Woodruff where Achsah May lived until 1897. But the emigration of her parents was not yet completed. In 1901 they again went back to Logan, Utah, where her parents resided until their deaths in 1910.

One Sunday when Achsah May was a young child and her brother Wilford was still younger, her father went to Lone Pine. He was so absorbed in conversation with a fellow traveler that he forgot to notice where he was driving and he calmly, or, it was decided, uncalmly, dumped his whole family in the Show Low River. When his wife came up, she was screaming voluminously with her baby clutched desperately under one arm, her other hand grasping a wagon wheel and both feet kicking about wildly in search for little Achsah May. “Aha,” said the fellow traveler suddenly and reached for a tiny bit of debris floating about. As he pulled, up came Achsah May. She had fallen with her head down so that she had fastened in the single trees of the wagon. A noble deed was done that day for my mother’s life was saved. But more important to the child was the beautiful pair of shoes she had on. The first thing she said after regaining consciousness was, “Are my white kid shoes spoiled?”

Just before moving back from Idaho to Woodruff when Achsah May was sixteen, she did a very daring thing—she cut and curled bangs all across her forehead. So at last Achsah May became a young lady. This cutting of bangs was something on the order of a coming out party.

While living in Woodruff, she kept house for her mother and went to school. At the same time she participated in various Church activities. In 1892 she became a counselor in the Young Ladies’ organization. In 1895 and 1896 she was secretary of the Primary organization and in 1896 and 1897 secretary of the Sunday School.

Woodruff, in and before the “Gay 90s,” was the business center through which all the mails and freight to Fort Apache passed.[32] Then also, the Woodruff dam was “in,” and Woodruff was a very prosperous farming community. Midst the gaiety and hilarity then so prevalent in the community, Achsah May was a prominent participant. In fact she turned out to be a second Pasteur in the little town, or at least, an advocate of sanitation.[33] She is noted as being the maker of the first screen door ever made in Woodruff. With stimulus, other screens were used, in doors and windows, and thus helped to abolish many contagious summer diseases.

Strange to say ‘twas written in the stars that Louis Addison Decker and Achsah May would someday meet and wed. Both of them had been saved from drowning when young children. When Achsah May first met Louis, he was singing at an annual MIA convention entertainment. She thought Louis was slightly off key and laughed at him, but a few months later when he sang, “I Love You Truly,” she thought he was definitely in tune. On October 1, 1897, they were married in the temple in Salt Lake City, Utah. In those good old days, the young people hitched up a horse or two, packed a bushel of oats, lassoed a chaperone, and trotted up to Utah to be married. Louis and Achsah May trotted along or jogged along for seventeen days. Then Achsah got herself a new bonnet and married Louis.[34]

Upon returning from Salt Lake and Parowan, where they visited with relatives and friends while spending their honeymoon, they settled in a snug and neat log cabin in Taylor. There the stork stopped by at intervals until he had left them ten children. With her responsibilities of wife and mother, she has rendered her greatest service.

In the Taylor Ward, she was active in Church affairs. She was Sunday School teacher of the First Intermediate department where she especially enjoyed her work. As a child she received a complete and beautifully bound volume of Shakespeare’s works for her remarkable work in Sunday School. This book has become a family heirloom and a priceless possession. From 1899 to 1904 she was secretary of the Taylor Relief Society and from 1901 to 1905 a counselor in the YWMIA.

When she moved out to Day Wash in 1916 to help her husband in his land and sheep projects, she was truly a pioneer but nevertheless one of spirit, of determination, and with an aesthetic love for beauty and art which has never diminished with the years.

The dearest memories of her children are the fascinating tales of love and devotion with which she lulled them to sleep. Her greatest assets have been her love for mankind, her deep understanding and a deeper quality of true character which has made her a friend to all. She has been a faithful wife, helping her husband teach their children what they have believed to be the only true path of a good and abundant life.

The sacrifices of her life have held within them a recompense. There have been many sorrows with the joys, but the joys have overshadowed the disappointments.

Many times has death’s hand cast its shadow too near her, so near that only heavenly clemency has saved her life. In 1913, she was attacked by pneumonia. Her recovery was considered impossible by physicians, but in those circumstances, Achsah May has found that there “is a greater love than death”—the love of God.[35]

When a girl, she took a course in obstetrics, which has been invaluable, not only in the rearing of her own family but in helping out many women in a pioneer age, before medicine had advanced to its high stage. Never has she been unwilling to lend her hand when she was needed. Always a patient and kind nurse, she has at least aided in preserving health and life. And in this service to friends, to her family, and to her children, she has received the most happiness. In giving, she has found her greatest joy.

All her life has been spent in an earnest desire to find the beautiful things of life and to live soberly and well. We read in the Book of Mormon, “I perceive that thou art a sober child, earnest, prayerful, faithful.”[36] Achsah May was such a child. She has been faithful to the duties of home and church. She has been childishly sincere in her pursuit of right.

At Aripine, she served as president of the Primary for four years. In the Snowflake Ward she taught the Trailbuilder boys in Primary for two years. She was captain of the Snowflake camp of the Daughters of the Arizona Pioneers from 1930 to 1934 and is now serving as county chaplain for the same organization.[37]

Not yet sixty, her duties of life not finished, she smilingly challenges life, not with the daring of impetuous youth, nor with the surveillance of tottering old age, but calmly, serenely, trustfully. Surely, the years hold nothing but beauty for this good and faithful woman who has done good, not that good might be done to her, but that she might obey the edicts of a Supreme ruler.

Life—just the privilege of working, laughing, whistling (Achsah May’s favorite pastime even now), and loving have meant so much to her. Life has not been a farce to her but the greatest privilege she could desire. She has lived it well! May Hatch Decker passed away September 3, 1964.

Ellis and Boone:

Not mentioned in this sketch was May’s son Joy. When the Decker family lived at Aripine, they lived near Fred and Wilma Turley. Their daughter Wanda Turley Smith remembered that “one of the sons, Joy, had cerebral palsy but a very sharp mind. I remember my father would play a bidding domino game with him (sort of like a bidding card game). When my dad played with us children, we always had to have our minds on the game and play as quickly as we could. It amazed us the patience he had playing with Joy, whose every movement was such an effort. Joy was SO excited if he could beat my dad!”[38]

Two additional stories from a book prepared for the Taylor centennial also help illustrate the life of May Decker. Both of these stories tell of devotion, although the first was told with an emphasis on humor rather than spirituality: “While the Decker family [was] having their usual family prayer, which [was] always fervent and sometimes prolonged, little Alma Decker silently left the group and climbed up on the table and drank all the milk.” The family was then left “with only bread for supper,” although the common pioneer fare was normally bread and milk.[39]

Then in 1910, Louis Decker accepted a mission call to California and left May to take “care of the six little Deckers as best she could. They had chickens, pigs, and a good garden and orchard from which they lived nicely. The good men of Taylor hauled her wood. . . . Each fall the neighbors would come and kill the fat hog. When one was killed, salted down and cured, Uncle Jim Shumway always put a new little pig in the pen to take its place.”[40]

The help that Taylor men gave these missionary wives can also be seen in the following story, although it may or may not be about May Decker: “A man was called to go on a mission for the L.D.S. Church from Taylor and had no time to get ready financially, so he went to A. Z. Palmer [who owned a store] and asked him to see that his family had food and clothing while he was gone and he would pay him every cent when he returned home. Well this man was gone for two years, and when he came home he came immediately to my father and asked him how much he owed him. My father leafed through the books and told him he owed two hundred dollars. The man said, ‘Now Brother Palmer, you know it’s much more than that, come on now, tell me how much.’ My father said, ‘I can’t charge you for anything that is not on the books.’”[41]

Emma Seraphine Smith Decker

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Emma Seraphine Smith

Birth: August 12, 1853; Parowan, Iron Co., Utah

Parents: Jesse Nathaniel Smith[42] and Emma Seraphine West[43]

Marriage: Zechariah Bruin Decker;[44] October 4, 1869

Children: Mary (1871), Zechariah Nathaniel (1872), Louis Addison (1873), Emma Constance (1875), Inez Gertrude (1877), Jesse Moroni (1879), Nancy Clementine (1881), Daphne (1883), Claßrinda (1885), William Curtis (1887), James Alvin (1889), Silas Smith (1892)

Death: December 29, 1909; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Emma Seraphine Smith Decker was born August 12, 1853, at Parowan, Iron County, Utah. Her father, Jesse N. Smith, wrote about the event thus: “August 12, Friday. At 1:00 a.m., my oldest daughter was born. We named her Emma Seraphine.”[45]

A few letters that she and her mother and a sister wrote during the years that she was a young girl have been preserved and are prized possessions of her youngest child, Silas Decker. In one of these letters, dated November 12, 1868, when she was fifteen years of age, Emma Seraphine Smith asked her father, who was then on his second mission to Scandinavia, if he thought she had better teach school that winter. His answer was not saved, but she taught school the winter before she was sixteen.

Another letter (written by a boyfriend, Zechariah B. Decker) was dated April 17, 1869, and reached Jesse N. Smith May 21, as he wrote, “asking me for my oldest daughter for a wife; [I] replied that I had no objection if he would live where there would be protection for her against the insults of strangers.”[46]

Emma Seraphine Smith Decker. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Emma Seraphine Smith Decker. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

A letter from the mother of the girl in the story [was] written on the back of Z. B.’s letter, stating that, though the lad seemed a little green, she believed he was honest.

No one knows for sure whether this accompanying letter helped or hindered Jesse N. to make his decision, but anyhow the wedding took place October 4, 1869, in Salt Lake City Endowment House. A letter signed by Emma Seraphine Smith Decker written a few days later announced to her father that she had been endowed and sealed to Z. B. Decker on that date.

There were twelve children born to that couple. The first one died the day she was born. Another daughter died in 1883 at two years of age; then in the year 1887, between September 27 and October 6, four more of the children died.[47] The other six lived to maturity, and all but one raised children.

The way Mrs. Decker lived through the losing of so many in so short a time was an example of courage and common sense, which inspired courage in some of her sisters and friends who likewise lost some children.[48]

In other years and other experiences, she always made the best of what life gave her. She enjoyed many experiences among friends and relatives. She met unpleasant experiences that go with pioneer life. The fact that those were times when savage Indians made life rather uncertain and fearful or when white ruffians were a bad threat to peaceful living brought some unpleasant experiences.

The Deckers pioneered, and a lot of that pioneering was in frontier parts of the country away from the settlements. One of those frontiers was in San Juan Country after the episode of renown at the Hole-in-the-Rock. Perhaps Jesse N. Smith envisioned the rugged individualism of Mr. Decker when he gave a challenge along with his consent for the marriage of his young daughter to such a man.

Emma Seraphine Decker through all her life accepted responsibility with a will to perform readily. She loved to cook for and entertain company. She was never a shirker of responsibility as bishop’s wife, Primary or Sunday School teacher, ward Primary president, or stake Primary president. This latter office was held by her when her last terrible sickness and death occurred December 29, 1909.

Ellis and Boone:

Z. B. and Seraphine Decker, with their five children, were part of the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition of 1879, which sought to open a new and more direct route into the San Juan country of southeastern Utah.[49] Zechariah Bruin Decker Jr. was elected captain of the fifth ten.[50] As Hartley explained, “A ‘ten’ was a group of roughly ten wagons. This unit was the workhorse in the pioneer company organization. A captain of ten knew everyone in his group, and they camped together; the whole company did not camp as one. A group of ten dealt with problems such as breakdowns, illness, or death. A captain of fifty was an ‘executive director’ and kept track of how his five tens were doing.” It was during this trip, before the group reached the Colorado River, that Seraphine helped with the birth of Mons and Olivia Larson’s son John Rio. On February 21, 1880, Olivia gave birth during a terrible snowstorm while she “was lying on a spring seat and her husband was trying to pitch a tent so the mother could be made more comfortable. With the help of sister Seraphine Smith Decker and brother Jim Decker, she was placed in the tent and made as comfortable as circumstances would permit.” Three days later, Olivia Larson was ready to “move on [and] join the company which had gone ahead.”[51] It is presumed that the Deckers traveled to Arizona from Bluff to Moenkopi and then up the Little Colorado River; they were living at Bluff for the 1880 census.[52]

Four generation photograph of Jesse N. Smith (seated), Emma Seraphine Smith Decker, Zechariah N. Decker, and Edwin Zechariah Decker (baby) about 1897. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

Four generation photograph of Jesse N. Smith (seated), Emma Seraphine Smith Decker, Zechariah N. Decker, and Edwin Zechariah Decker (baby) about 1897. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

This sketch for PWA is very brief. Descendant Jesse Smith Decker provided a few more personal details of Emma Seraphine’s life. He wrote, “She was the first child of Jesse N. and Emma Seraphine West Smith, and the oldest of forty-four children of her father and his five wives. [Therefore] from an early age, she was designated to help her father in the fields. She loved the soil and the outdoors and helped until the boys grew old enough to take her place. She did not have household training or cooking experience as the other girls, but was trained in schooling from that excellent teacher, her grandmother, Mary Aikens Smith, with whom she shared a bedroom while she was growing up.” He later added, “She had to learn to cook after she started housekeeping. She had to get help to cut up her first chicken but experience made her quite efficient. . . . But all her life she would rather read or teach than do housework. Her daughter-in-law, Mae Decker, [wife of Louis] tells of how [Seraphine] would always read the paper she was starting a fire with, even though the house was cold and they needed a fire in a hurry.”[53]

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt

Autobiography

Maiden Name: Margaret Miller Watson

Birth: January 10, 1841; Annit Hill, Lanarkshire, Scotland

Parents: John Watson and Jane Hosea/

Marriage: Abel Alexander DeWitt;[54] March 15, 1860

Children: Lucy Jane (1861), Sarah Hulda (1863), Abel Alexander (1865), Elijah Reeves (1868), Elizabeth Catherine (1870), Margaret Lenora (1872), Martha Ann (1874), John Daniel (1876), William Washington (1879), Rhoda Ellen (1881), Jesse Dillis (1883), Mary Eliza (1885)

Death: February 28, 1930;[55] Woodruff, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Woodruff, Navajo Co., Arizona

I was born in Glasgow, Scotland, Amet Hill, Mankland Parish, about eight miles from Glasgow proper, January 10, 1841. I was the youngest of a family of nine children. My father’s name was John Watson, and my mother’s was Jane Hosea Watson.

Among my earliest recollections of my father, who died when I was a small child, is my seeing him, wrapped in quilts and seated in a chair while I played. I played peek-a-boo with him through the glass in our door.

When I was about twelve years of age, my sister Jane, six years older than I, joined the Mormon Church and emigrated to America a year or so later.[56] The other members of the family felt that by doing so she had brought great disgrace to our family.

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

My mother died when I was twelve years old, and I lived with an elder sister, Belle, who sold the place and rented one little room for the two of us. During this time, my sister Jane wrote to me in care of a friend, Agnes McKay, urging me to attend the Mormon meetings and investigate their religion for myself. I did so secretly, going to their meetings when my sister Belle supposed I was attending night school.

I was able to attend several meetings conducted by the Mormon elders before my sister discovered my deception, which she finally learned from the factory girls where I worked. Thinking she was doing the proper thing, she gave me a severe whipping and warned me not to go near the elders again. However, this only served to strengthen my determination to find out for myself all about Mormons and Mormonism.

I still continued my secret correspondence with my sister Jane, who lived in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and she sent me money to pay my passage across the ocean. I remember going to the bank and getting the money which I concealed in the bosom of my dress in the daytime and in my shoe at night. Very soon after this I left my sister Belle’s home. We had eaten breakfast, and I left as if I were on my way to the factory. I saw the clothes spread on the green to bleach (she had washed the day before) and I picked up my night cap and slipped it into my pocket. This was all that I took with me except the clothes I stood up in.

I went directly to my friends, the McKays, who informed me that the next sailboat would not leave for two weeks. I couldn’t go back home to Belle, so my kind “Mormon” friends, the McKays, hid me up for two weeks in the home of a widow who boarded me: the McKays outfitted me with clothes for my journey.

Bills had been posted and rewards offered for my capture, so, fearing detection, I disguised myself when I went to the sailboat. Just before boarding the ship, I posted a letter to my sister Belle telling her not to continue her search for me as I was on my way to America. I crossed the gangplank and entered the ship. Then I went below into the steerage until the ship had started.

I then went up on the deck and took a last fond farewell of my native land. I was overcome with conflicting emotions as I saw it disappearing from my sight. For, though I was glad and eager to come to America, where I could learn more about “Mormonism” and join my sister Jane, yet I felt sad to leave forever my native land, my brothers and sisters, and friends. I extended my arms and cried, “Good-bye forever, old home;” and the ship, the Isaac Wright, bore me off.[57]

Soon after leaving I became violently seasick, and lay on the bare deck for relief. Having taken nothing with me except my clothing, I had nothing to lie on. A young woman came near me, saying, “How’s this? Haven’t you any folks to look after you? But no, I mustn’t talk; I must do something.”

She went to the cook room and made a little tea and toast. As I partook of it, my stomach became settled, so that I could get up and get around. Soon I became adjusted to life on board ship. From Liverpool to New York, we were on the sailing vessel six [five] weeks and three days.

When we landed at New York, the McKay girl’s folks met us there. A large crowd was present as we were getting off the ship. I kept saying aloud: “O have you seen my sister?” I hadn’t heard the popular song being sung, entitled, “O Have You Seen My Sister?” At once someone in that great throng caught up the words and sang it while the whole merry crowd began singing and laughing.

I took the train from New York to Springfield, Massachusetts, where my sister met me. Words cannot express the joy of our meeting. I went with her to her home in Holyoke. There I remained with her and a group of emigrant girls. We worked in a factory, earning the money to pay our way to Utah. Having had experience in working in the factories in Glasgow, where there were five hundred steam looms on one floor, I felt at home in the work. They started me out with two looms; when my sister saw that I could handle them easily and still have plenty of spare time, she said to the manager, “My sister is an ambitious little girl and I’m sure she can handle more looms when you can give them to her.”

They gave me four for a while, but soon increased it to six, the most ever given to any experienced girl in the factory. I made it a point always to be prompt; and the watchman would laugh as he held his lantern so that he could see my face as I sat at the big doors each morning waiting for him to open them and let me in. The minute the engine started I was at my loom. Some of the girls were always ten minutes or more late; when they remarked at my higher wages on pay day, it was pointed out to them that ten minutes each day will soon amount to dollars and cents.

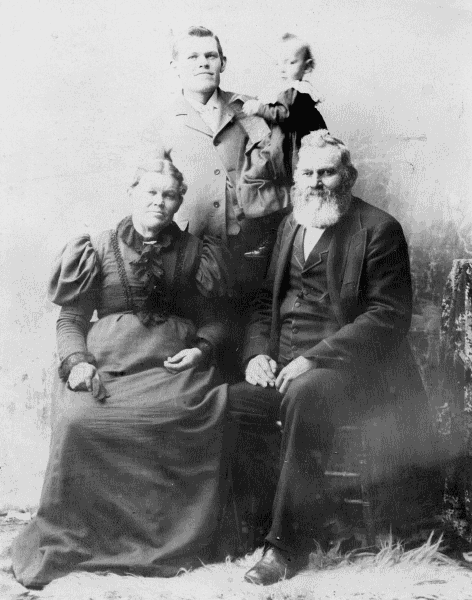

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt (seated) with husband Abel Alexander DeWitt, son Jesse and wife Maud Jarvis Dewitt (standing), baby unidentified; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt (seated) with husband Abel Alexander DeWitt, son Jesse and wife Maud Jarvis Dewitt (standing), baby unidentified; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

We received our pay in an office adjoining the factory. Here two men counted out the money, which was held in a big, seamless sack. The books were opened and the numbers of the looms were given. Then the girls were paid in cash. As I received my wages, I often heard the men whisper to one another, “Is that the one?” I was small for my age and my skill as a factory hand was talked about among the workers.

We worked in this factory for about two or three years. Our boarding house was managed by two old maid sisters who had rented a large house especially for factory girls. We paid them each month; and outside of our board, lodging and clothes, we saved EVERY CENT for our journey across the plains.

My sister left for Utah three weeks before I did, as there was not room for both of us in the first company.[58] I handed to the president of the branch sixty dollars in cash to pay my way to Utah.

Before leaving for Zion, however, I had been baptized and confirmed a member of the Church. My sister and I had attended regularly the LDS services in Holyoke. Each meeting strengthened my faith, though I had believed the gospel to be true from the first time I heard the elders preach it in Glasgow. On account of the bitter opposition manifest by the anti-Mormons there, my baptism was performed at night. When I was taken to the river the ice was broken, and there I was baptized.

I traveled across the plains with Thomas Lyons, his invalid wife, and five children.[59] They had two hired teamsters, each driving a large wagonload of goods. I took care of their five children and cooked every bite that was eaten by our outfit of ten, from the time we left Florence, Nebraska, until we reached Salt Lake City. I walked all the way across the plains, carrying the baby much of the time. Sister Lyons had to be lifted in and out of the wagon, and had a special chair to sit on.

As soon as the men would pitch tents each night, I would prepare supper over an open campfire, then get the children to bed. Often I did not get much sleep, the mosquitoes being very troublesome, and causing the children to cry and fuss a great deal. I had never cooked over a campfire; when I needed information I counseled with some of the older sisters, who were very kind to me. I learned to bake light bread in a bake oven. From each baking, we saved a piece of dough for our next batch of bread.[60]

There was one death in our company—an invalid man who could not stand the trip. His body was wrapped in canvas and buried in a grave, by which a service was held. All along our way we saw graves which the coyotes had dug into. I remember a marriage on the plains. After the ceremony, we danced most of the night to the music of a fiddle. When we were about half way across the plains, I had to leave my new trunk because we were too heavily loaded. My clothes I put into sacks.

We were three months crossing the plains, under the captaincy of Edward Stevenson. My sister heard of the company through the “pony express” and was ready to meet me. She had arranged for a place for me to work—for a Sister Howard, who lived eight miles south of Salt Lake City at Big Cottonwood. My sister had a place in Salt Lake City, and we often visited.

With the first money I earned in Salt Lake City, I purchased a new chest for my clothes. This was made by a Brother Thomas Ellerbeck, an excellent carpenter.[61] I still have this chest and it’s as good as new.

The date of our arrival was September 16, 1859, with 350 souls and 150 wagons. That evening in the Howard home as I stood by the sink washing dishes, I noticed a young man come into the room—a tall, straight, handsome fellow. I nudged Sister Howard’s daughter, who was wiping dishes, and asked, “Who is that?”

“Don’t get your heart set on him, because I already have my cap set for him,” she answered. I replied that I did not want to fall in love with anyone. About six months later, however, when I was nineteen years old, this same young man became my husband. I had no parents to go to for advice; so when he proposed marriage, I went to Bishop [David] Brinton and asked him to advise me. His answer was, “You’ll make no mistake, Margaret, if you marry Alec DeWitt.”

Sister Howard had been like a mother to me; at the time of my marriage she dressed me completely in the very best of clothes. My wedding dress was a beautiful white, tucked all around the full skirt and with lace and white ribbon. Sister Howard engaged Eliza R. Snow and Sister Woodmansee to come to her home a week and sew on my wedding dress, sheets, pillow cases, quilts, and everything preparatory for my marriage.[62] I felt like a princess to be so honored.

The bishop, who was to marry us, was working on the jury that day; but he walked eight miles to our ward that afternoon in order to perform the ceremony that night.

I had been afflicted with a sick headache during the afternoon, and Sister Howard had sent me to bed. While I was there, she and her daughters had fixed up our little two-roomed cottage, which Brother DeWitt had rented for our future home. I was dressed in my wedding finery as we walked to the bishop’s home where we were married. Then we went to our little home.

I noticed that it was all lighted up; and we entered, we beheld a table laden with a feast—roasted chicken and everything that goes with it. My bed was all made up with new sheets and pillow cases and the beautiful quilt that Eliza R. Snow and Sister Woodmansee had made. We spent a happy evening with the Howard family and the bishop’s family. Mrs. Howard was an excellent cook, and the banquet she and her girls had prepared was delicious.

Brother DeWitt had brought a load of furniture from Salt Lake City; it had been unpacked and put in place. The new dishes were in a cupboard he had made. All this was a surprise to me.

Prior to our marriage, my husband had been investigating “Mormonism” and was really converted to it, but postponed being baptized because he did not want it said of him that he joined the Church to get the girl he wanted. He was baptized about two weeks later.

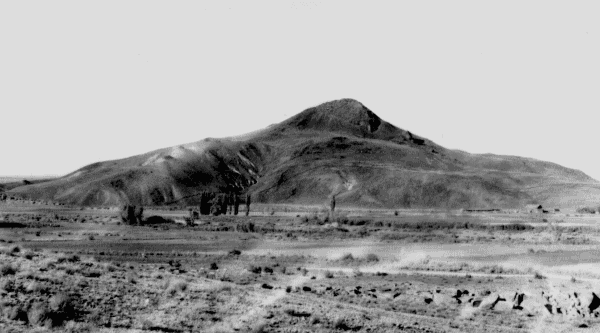

An old volcano known as the Woodruff Butte is the most prominent landmark between Snowflake and Holbrook. The town is located to the south and at the base of the butte. This arid landscape receives only 8 to 10 inches of rain per year, which means all crops depend upon irrigation - and makes one wonder why Margaret DeWitt moved from Springerville to Woodruff in 1891; Max R. Hunt, photographer, ca. 1950. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

An old volcano known as the Woodruff Butte is the most prominent landmark between Snowflake and Holbrook. The town is located to the south and at the base of the butte. This arid landscape receives only 8 to 10 inches of rain per year, which means all crops depend upon irrigation - and makes one wonder why Margaret DeWitt moved from Springerville to Woodruff in 1891; Max R. Hunt, photographer, ca. 1950. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

My husband, Abel Alexander DeWitt, was born October 6, 1826, in Perry County, Indiana. He had traveled extensively—had been in South America—and was on his way to California to seek his fortune. Although he had heard about the Mormons in Salt Lake City, he really feared stopping there for fear they would kill him; he finally found a job and stopped at Howard’s. There he investigated “Mormonism” and embraced it. He died at Woodruff, Arizona, September 16, 1913.

While living at Cottonwood, we were blessed with six children; Lucy Jane was born March 28, 1861, and died at Salt Lake City July 16, 1923.[63] Sarah Huldah was born March 26, 1863, and died November 18, 1904, at Lehi. Alexander was born October 1, 1865, and is still living. Elijah Reeves, born February 18, 1867, still lives. Elizabeth Catherine, born June 5, 1870, died April 29, 1904, at Thatcher, Arizona. Margaret Lenore was born July 20, 1872, and died August 13, 1873, at Big Cottonwood.

We moved to Kanab, Utah, where our next three children were born: Martha Ann born October 8, 1874, died December 29, 1879, at Kanab. John Daniel, born November 5, 1876, is still living. William Washington was born January 10, 1879, and died December 1, 1907, at Woodruff, Arizona.

We were called by Church authorities to cross the Colorado and help settle Arizona, so we moved to Springerville, where our last three children were born: Rhoda Ellen, born March 27, 1881, died October 24, 1888. Jesse Dillis was born April 23, 1883 and is still living. Mary Eliza was born July 24, 1885, and died on the same day.

When Jesse was about eight years old, we left Springerville and came to Woodruff, where I am still living.

When my last child was born, I was at death’s door, but through the faith of the elders I was spared. Word went out: Sister DeWitt is dying. The elders left a 24th of July celebration they were attending; they came and prayed for me, and I rallied.

I was set apart as Relief Society teacher after my first child was born. I have served as an active teacher in that organization ever since—a period of sixty-seven years. I am still an active teacher in the Woodruff Ward. I used to go teaching in Big Cottonwood, carrying my baby on my arm. The bishop’s wife, Sister Brinton, used to say, “Be sure to stop last at my house.” She would always have a delicious supper prepared, saying to us, “The servant is worthy of his hire.”

Though I am now eighty-eight years of age, I still enjoy working in the capacity of a Relief Society teacher—a calling that I consider one of the greatest.

Margaret died February 18, 1930, at age eighty-nine.

Ellis and Boone:

Margaret Miller Watson DeWitt’s autobiography was first published in the Relief Society Magazine in 1929.[64] Her account of crossing the ocean has more detail than many sketches and has recently been republished with other crossing the ocean stories.[65] LeRoy and Mabel Wilhelm tell a little more about the DeWitt’s move from Utah to Arizona:

A.A. DeWitt . . . came into Arizona in 1873 as a leading member of Captain Haight’s Company, which came under the direction of Brigham Young.[66] Fearing that the Petrified Forest regions were unsafe for colonization, the party hurriedly left, but DeWitt insisted on carrying out the president’s orders and explored further. Lack of provisions also forced him to turn back. With his family he spent the winter of 1879 in Brigham City. En route to this settlement, they met the Richey company on its way to Salem [one mile north of present-day St. Johns], and spent several evenings singing and dancing with this happy group.

In the spring of 1880, the DeWitts came on to Salem, purchased a lot, and then went on to Amity [Eagar].[67]

In 1891, the DeWitt family made Woodruff their permanent home. Margaret’s contribution to the family income is seen in this note from a history of Woodruff: “A store was established in 1895 by Margaret DeWitt, with a total capital of one dollar. She built it up to a fine, flourishing business. Seventeen years later she sold the store to James Brinkerhoff for two thousand dollars.”[68]

Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt

Author Unknown, Interview

Maiden Name: Sarah Wilmirth Greer

Birth: March 30, 1872; Kopperl, Bosque, Texas

Parents: Americus Vespucius Greer[69] and Polly Ann Lane

Marriage: Elijah Reeves DeWitt;[70] December 31, 1890

Children: Elijah Greer (1892), Gilbert Irvin (1896), James Vance (1901), Helen (1904), Wallace Barnett (1906), John Paul (1913), Americus Alexander (1916)

Death: July 4, 1957;[71] St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Wilmirth Greer DeWitt was born in Kopperl, Bosque County, Texas, on March 30, 1872, the daughter of Americus Vespucius Greer and Polly Ann Lane Greer.[72] When she was five years old her parents joined the Mormon Church and came to Utah, staying there only a few months, then moving to Arizona. Thus they started one of the most interesting and inspiring stories of an Arizona Pioneer family among all the wonderful stories and experiences recorded by these wonderful pioneers.

Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Her father became one of the best known and most respected of the early settlers of Northern Arizona. He settled the little town of Amity (meaning friendship) about three miles southwest of Springerville, where he helped to build the first schoolhouse and was its first teacher. The hardships of pioneer life were too severe for the frail, delicate mother and three years after their arrival in Arizona, she passed away, leaving her husband with a family of six children to raise alone, the eldest was a daughter of fifteen and the youngest a baby boy of two years.[73]

Wilmirth, who was then ten years old, went to live with her aunt on the famous Greer ranch between St. Johns and Holbrook. When she was thirteen her two older sisters were married, and she went home and assumed the responsibilities of caring for her father and three younger brothers. They lived in a two-room log cabin, where she did all of the cooking over a large fireplace with a black pot hanging from an iron rod over the fire. On Monday mornings, they would heat a large tub of water over a fire, and she would put out the week’s washing for the family by hand before going to school.

When Wilmirth went to school, she would prepare the beans or other vegetables, the stew or the meat, whatever the bill of fare for that particular day might be, and the father would keep it cooking until the children came home and the meal would be all ready.

The winters were very severe, the snow often drifting from four to six feet, and on a level it would measure two feet deep. There was always plenty of wood and often times plenty of company, as “Uncle H” was a true son of the South and his hospitality was known far and near. Wilmirth soon learned to be a gracious hostess, and her father never hesitated to bring friends home because he knew if there was anything in the house to eat, his daughter would have it fixed in a most appetizing manner. Mr. Greer got his supplies from Albuquerque, New Mexico, and it would take a month to make the trip.

Wilmirth said: “We used to get out of foodstuffs and many times I have made cornbread from corn I had grated on a homemade grater. It was real good, too. We used to grate our potatoes and wash the starch out of the pulp to starch our dresses. These are only a few of the inconveniences we had, but in spite of all we were very happy, and had ample time to enjoy ourselves in the good old fashioned dance and other amusements. We used to be greatly alarmed on account of the Indians, as this was when Geronimo, the great Apache warrior was on the warpath. The men would have to take turns standing guard at night to protect their homes and belongings. Large bands of Indians would pass through the valley but they never bothered us. Our greatest trouble was with outlaw white men who would steal our horses and cattle and cause trouble in many ways, but as civilization advanced, our troubles grew less and we were contented and happy.”[74]

When she was eighteen she met and started keeping company with Elijah Reeves DeWitt. He would come to take her to the dances or other amusements in his wagon or on a horse, and she would ride behind him on the horse. They were married on December 31, 1890, in the St. George Temple, driving all the way from Springerville to St. George in a covered wagon. Two other couples were in the party. The trip was uneventful until on the return they had the misfortune to have two of their horses killed by a train, one horse out of each team. They put the remaining two horses on one wagon and left the other one, Mr. DeWitt going back later to get it.

Of life immediately following their marriage she stated: “We continued to live with my father for the first two years as I could not bear the thought of leaving them alone. At the end of that time my eldest brother married and shortly after that my father died, and then we moved to ourselves.” Their first child, a son named Elijah Greer, was born a year after their marriage. Her husband homesteaded a ranch in “Lee Valley,” now called Greer, in honor of her father. A description of their first home, written by Wilmirth herself follows: “The cabin was 14 x 18 feet with one window and a door; we put the stove in the west end, the table in the northeast corner, our bed in the southwest corner and I nailed a box on the wall in the northwest corner. I put a curtain around the box and a mirror on the wall above it and this was my dresser. The walls were papered with newspapers, and we were very happy.”

Upon moving to the new home in Lee Valley, Wilmirth helped her husband to build their cabin and fence the farm. She would go into the woods with him, laying the baby on a blanket under a tree while she would take the horse and “snake out” poles which her husband would cut. When enough were cut to load the wagon, they would load up and haul them to where they were fencing their farm. They lived here about eight years. Each summer Wilmirth would milk cows and make butter or cheese, which she would take into the Becker Mercantile Company in Springerville, making the trip over the rocky roads in a wagon.[75] Their second son, Irvin, was born here, and when he was about three years old, Elijah received a call to go on a mission for the Mormon Church. As is customary, he accepted the call and sold the ranch and moved his family into Eagar where he built for them a three-room house. The Lee Valley homestead is the property now known as Reeds Lodge.

While Elijah was on his mission, their second son died, and she had to suffer the loss alone. During the two years her husband was gone she had no money, but enough to eat, and was happy to have him serving the Church. She tells of going out in back of the house and finding a venison, ham, or other part of a deer. Whenever it seems that they needed some meat, this would happen, and she would know that Jacob Hamblin had been there, leaving the meat without ever waiting to be thanked.[76] Such was the spirit of help and cooperation among the pioneers. At one time she sold a calf, the only one they had, for six dollars to get some money to send to her husband, that he might buy some material needed for his missionary work.

Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt (right) with her sister Susan Greer Hamblin; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Familiy History Library.

Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt (right) with her sister Susan Greer Hamblin; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Familiy History Library.

When Elijah returned from his mission, they took up their life in Eagar, where they were both very active in the affairs of the Church, a practice which she continued as long as she lived. She was president of the MIA, and Elijah was a counselor in the bishopric. Both were talented and many were the plays, musicals, and other cultural pursuits they were responsible for.

In 1910 they sold out and moved to Chandler, Arizona, Wilmirth driving a team all the way before any of the modern roads were built. She afterwards said that driving a wagon over the Fish Creek Hill road was what turned her hair gray.[77] In Chandler she helped her husband clear and plant a farm, located at what is now Nortons Corner, four miles south of the town. They sold this place two years later and moved to St. Johns, where they lived for the next ten years, and where their children grew up, and where their first son, Elijah Greer died in 1918, a victim of World War I. They also lost their youngest son, Alex, in 1921. Aunt Wilmirth, as she was known to all the young folks in town, was one of the most loved persons in St. Johns. Her home was always open to them for candy pulls, tamale parties, or anything they desired. She was always faithful to her church duties.

In 1924 they moved to Tempe to help their children go to college, and the last three children, Helen, Wallace, and John Paul, all graduated from the college. They moved to Chandler again in 1928 where they engaged in the dairy business with their son Jim. While there, Wilmirth served as president of the Relief Society.

In 1933 they returned to St. Johns, where they remained until their deaths. Wilmirth died July 4, 1957, having lived just long enough to take care of her beloved husband as long as he needed her. He was seriously injured when hit by an auto and for the last years of his life was unable to care for himself.[78] Her love and devotion to him was an inspiration to all who knew her. About a year after his death she made the remark that “Life is not sweet anymore, with Papa gone. I wish I could go to be with him.” She died that night.