C

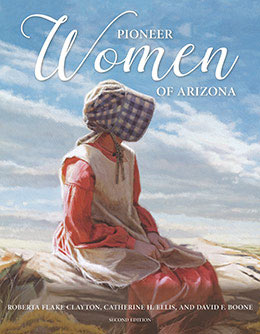

Albert Chlarson, Olive Kimball Mitchell, and Roberta Flake Clayton, "C," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 97-128.

Medora White Call

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Medora White

Birth: April 9, 1855; Farmington, Davis Co., Utah

Parents: John Stout White Sr. and Ann Eliza Adelaide Everett

Marriage: Israel Call;[1] December 21, 1874

Children: Israel Bowen (1875), John Anson (1876), Medora Adelaide (1878), Vasco (1880), Schuyler (1882), Chester Monroe (1884), Hettie Jane (1886), Ambrose (1888), Chloe Irene (1891), Vinson Oro (1893), Willard White (1895), Eldred Odell (1899)

Death: April 20, 1926; Bountiful, Davis Co., Utah

Burial: Bountiful, Davis Co., Utah

Medora White Call was the second daughter of John Stout White and Eliza Adelade Everett and was born April 9, 1855, at Farmington, Davis County, Utah.

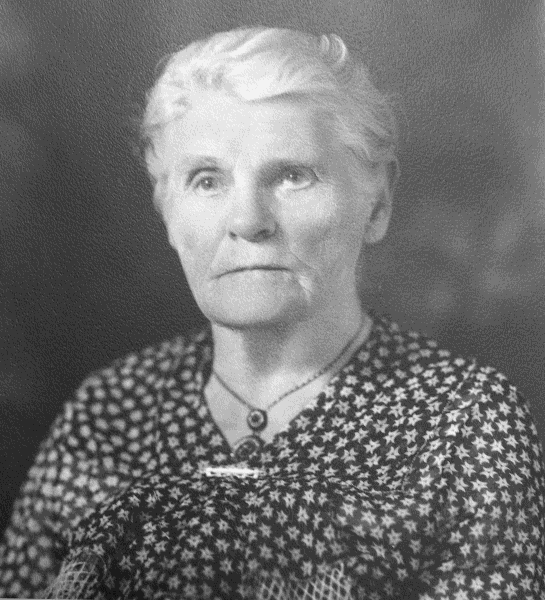

Medora White Call. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Medora White Call. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Her parents were very poor as far as material possessions were concerned, but were rich in devotion, honesty, and love. Medora was taught from early childhood to be thrifty, and she learned how to labor with her hands. When she was only a small child she had to herd the sheep and cows, help cut and thresh the grain, feed and milk the cows, hoe and cultivate the garden, haul hay, and she learned how to keep a clean house and was known for her good cooking.

Medora’s schooling was very limited. She graduated from school when she was in the third reader, but she always loved to read and study. She was known as the life of the party and was very popular with the younger set. She had a very sweet voice, and she learned to step dance and she continued that art throughout her life.[2]

Israel Call rode a mule the seven miles from Farmington to Bountiful while he courted Medora, and they were married December 21, 1874, in the old Endowment House, in Salt Lake City, Utah.

In the Spring of 1876, Israel Call and several other families from Bountiful were called by Brigham Young to colonize Sunset, Apache County, Arizona. All their earthly possessions were placed in the covered wagon. They arrived in Sunset in September 1876, after many hardships including crossing over Lee’s Ferry on the Colorado River where wagons had to be dismantled. This was an experience never to be forgotten because Medora’s baby was six months old, and her second son was to come, so the bumping, lurching wagon could have meant nothing but discomfort to her on that hard journey.

Thirty families lived the United Order during the ten years that they lived at Sunset. The Church owned everything they made, and they were given supplies according to their needs. They all ate at the same table. The women took turns cooking. They used open fireplaces to cook on. They appointed men to look after the sheep; some to look after the cattle.

They made a square fort which had two openings. The dining and kitchen space stood in the center of the fort, and the living quarters of the various families formed the walls of the fort. The garden and animal quarters were on the outside.

While at Sunset, five more children were born. The Saints had to have water, so they tried to build a dam. They hauled about fifteen tons of rock, but it wouldn’t hold because there was so much quicksand. Time and again the dams broke. When their son was born, there was no floor or window or door in the log cabin. They used a wagon cover for doors and windows.

In 1885, the Church authorities decided to locate other places for the Saints to live, and they sent Lot Smith and Israel Call to Mexico to find a place. This was the beginning of colonization in Mexico.[3] While he was gone his family suffered severe privations.

In September 1885, Israel Call, his wife, and six children left Sunset for Bountiful, Utah. During their stay in Arizona, Medora had become blind. Apostle George Teasdale came to Sunset at one time and promised Medora that if she would move back to Bountiful that she would regain her eye sight, which she did.[4]

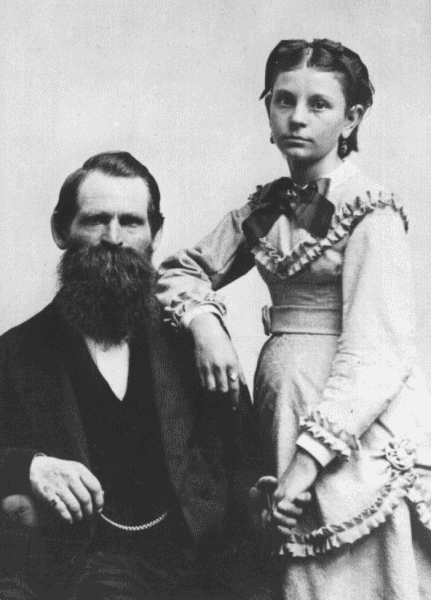

Israel and Medora White Call (left) in Utah with Samantha Evoline Call Mann and Willard Call, half siblings of Israel Call. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Israel and Medora White Call (left) in Utah with Samantha Evoline Call Mann and Willard Call, half siblings of Israel Call. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Medora was the mother of twelve children. Even with the hard life as a frontierswoman, she was happy and always had a smile on her face. Her house was filled with young people and her Sunday dinner was a must for young and old.

Medora passed away April 20, 1926, and was buried at Bountiful, Utah.[5] In writing about Mormon pioneer women, it must be remembered that for the most part they raised large families, and they did it while their husbands were away on Church assignments. This was true of the Israel Call family.

Vasco, the fourth child in the family, records some interesting items about his mother:

Mother was five feet tall and weighed around 230 pounds. Naturally she suffered with the heat especially when she was pregnant with her twelve children. They were raised in a one room cabin while they lived at Sunset, Arizona, and in two rooms at Bountiful. Their clothes were homespun and their food was homemade, so there was plenty for the women folks to do day by day. While she was blind at Sunset, the children would lead her around when she fed the animals and milked the cow. While at Sunset, Israel brought home a pretty widow with seven children as his second wife and they moved in next door. She would send the children to Winslow four miles away with butter and eggs to exchange for salt and sugar. The shade trees at Bountiful were mulberries and as the mulberries combined with dirt and were brought into the house with many bare feet that too would create a problem.

Israel was an ordinance worker in the Salt Lake Temple for thirty-five years where he was gone every day but Sunday. Someone had to keep the home fires burning and Medora was that one. Surely this mother has received her crown of glory in the celestial world after having lived as she did in the Second Estate.

Ellis and Boone:

The “pretty widow” mentioned by Vasco Call was Jane Lucinda Judd Knight, widow of Joseph Knight. The Knight and Judd families lived at Sunset, under the leadership of Lot Smith, and at Old Taylor. After an illness of six weeks, Joseph Knight, age thirty-eight, died on June 27, 1878, leaving a wife and seven children, ranging in age from twelve years to six months.

On June 11, 1880, Israel married Jane Knight as a plural wife. Israel Call and his two families moved from Sunset to Wilford (Heber) and later to St. Joseph. Israel and Jane had three children born between 1881 and 1885.[6]

Israel and Medora Call left Arizona in 1885 so Medora could receive medical treatment for her eyesight; Jane remained in Arizona. Israel returned to Arizona in January 1886, moved Jane to Taylor, and then returned to Utah in October 1886. As descendent Jackie Solomon wrote in her book about Joseph and Jane Knight, “Whether he [Israel Call] planned to return or told her he would not be back is a part of history we do not know. We do know that she was left with a great responsibility and without a companion.”[7] This return to Utah became a permanent move for Medora. Vasco was apparently the only one of her children who returned to Arizona to live.

Susette Stale Cardon

Unidentified Granddaughter[8]

Maiden Name: Susette Stale/

Birth: February 12, 1837; Angrogna, Torino, Italy

Parents: Jean Pierre Stale or John Peter Staley and Jeanne Marie Gaudin (Gaudin-Moise)

Marriage: Louis Philip Cardon; July 10, 1857

Children: Joseph Samuel (1858), Emanuel Philip (1859), Mary Catherine (1861), Louis Paul (1868), Isabelle Susette (1871)

Death: July 18, 1923;[9] Tucson, Pima Co., Arizona

Burial: Binghampton Cemetery, Tucson, Pima Co., Arizona

The Stale and Cardon families lived in the Piedmont Valleys in Prarostino, Torino, Italy. They were descended from the Vaudois or Waldenses [people] who broke away from the Catholic Church and from the twelfth century on were the object of persecution. This group finally settled in these high alpine valleys, where they were subject to many indignities, unjust taxation, kidnappings (especially the children), homes burned, and others, even as late as 1848, when they were permitted to enjoy civil rights and also political, but not religious, freedom.

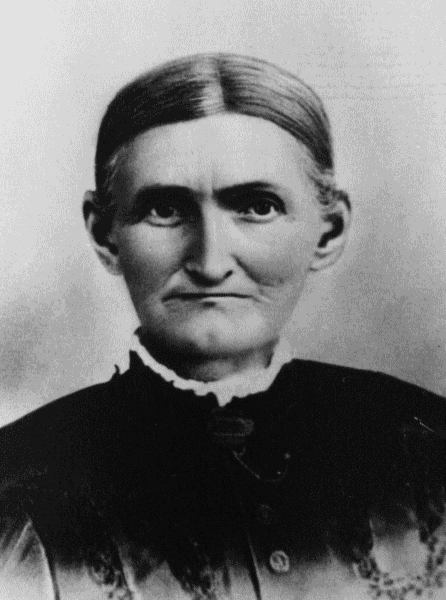

Susette Stale Cardon. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Susette Stale Cardon. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

It is significant that one year after toleration began in these valleys, Lorenzo Snow[10] and others were called at the October Conference in 1849 as missionaries to Italy, and Elders Thomas B. H. Stenhouse[11] and Joseph Toronto[12] were sent where Grandmother and her people lived. When they reached the valleys, there were about twenty-one thousand Protestants and five thousand Catholics.[13]

Jean Pierre Stale, and his wife, Jeanne Marie Gaudin, parents of Susette Stale, were both representatives of old Vaudois families. He, being unusually thrifty and prosperous, was considered well to do and had two homes, one on the sunny southern slope of a beautiful alpine valley where they cultivated grapes, figs, and other fruits, and the other almost straight up in the mountain vastness where they brought their sheep and goats in the summertime. Susette being the oldest child, took the responsibility of one place while her father did the other, thus learning at an early age to be reliable as well as active and efficient.

She was born February 12, 1837, at Angrogna, Torino, Italy, followed by her brother and sisters, Barthelmi Daniel, June 2, 1838, born in Angrogna; and Marie, August 15, 1845; and Marguerite, October 28, 1850 in Prarostino. The home life was thrifty, as they lived almost solely upon their own products—milk, cheese, fruits, grains, and all were utilized. Their bread was much sweeter than ours and was baked by her father, in huge ovens, two or three times a year. Her pets were her cows, which she cared for very carefully.

Susette had a long way to go to church, but she learned her catechism well and could quote long passages from it in her old age. Sunday School was the only school, the Bible was the text, and she was well versed.

When the missionaries came to the Valleys, she would go wherever a meeting was being held, regardless of distance or opposition. They were persecuted for joining the Church, property being destroyed, and the elders mistreated. One night she was at a meeting six miles from home, when a mob came, and she and her companions stood between them and the elders until they could slip away, being threatened by the mob. The family was baptized in 1852–54. Later in 1855, Franklin D. Richards and two companions, missionaries, were hiding from the mob in the high passes of the mountains and had been without food for three days.[14] They came to the Stale home and asked for something to eat. Susette ran out and milked the goats so they could have milk, while her mother prepared food and took care of other wants.

Brother Richards told them the family should go to Zion, but at first it was planned for Susette and her cousin, Madelaine Gaudin, to go first. There was so much bitterness that the father could not dispose of his property. Susette left for Liverpool, but Brother Richards, who realized it would perhaps be the last opportunity for any of the Saints to leave Italy, held the company, until the family “of the Girl who milked the goats” could get ready. Daniel was in the army, and it took some work to get him out to leave. They sailed on the ship John J. Boyd, from Liverpool, December 12, 1855, with about 500 Saints from several countries.[15] Immediately afterward the Italian Mission was closed. From New York they went to Winter Quarters, and then made preparations, and were in the first handcart company.[16]

We all have read of the trials and tribulations of this company. She and her brother Daniel pulled one handcart. She told many times that as it was so heavy, they would wear one set of new clothes until they became dirty, then throw them away. Others picked them up, and she saw a number of her dresses in Salt Lake City. It was a little more difficult, since they did not speak English, and it was hard to understand and be understood.

The father, Jean Pierre Stale, strove to help his family in all ways, even depriving himself of food so that they should eat more. He became ill and died August 17, 1856. The notation in the diary of the first handcart company outlined their day’s travels over sandy roads and several creeks, then “Camp at 4 P.M. on the side of the Platte, opposite Ash Grove. Brother Peter Stale died today. He was from Italy.” He was buried on the plains. Thus another unmarked grave was added to those who gave their all that we might be heirs to the greatest of all life’s blessings, the Priesthood.

The forlorn family traveled on to Zion. Grandmother said she heard people say those who came with the handcart companies spent evenings dancing around the campfires. She seemed to feel that they were tired from the weary miles, although she said they did sing and teach the gospel, reminisce and pray.

They stayed in Salt Lake City only a few days, then accompanied the Cardon family to Ogden, where they made a “dug-out” to live in. The floor was covered with fresh straw every Saturday when they could get it. They made beds and chairs from forked sticks put in the walls and floors, then wove rushes between. Several moves were made as they strove to make a living for the family as it grew up.

Her father had told her before he died that the day would come when they would have plenty, and as she got work, and her mother and brother also, things eased. They later moved to Logan, where Jean Marie Gaudin Stale married Philippe Cardon. Her daughter Marie married Elihu Warren, and Marguerite married Henry Barker.

Susette became accustomed to the strange life and customs in the new world, and her trials and troubles only made her faith and religion dearer. The 24th of July was sacred to her, and took precedence over every other anniversary. In 1857, she married Louis Philip Cardon, who had come to Utah four years earlier, from Prarostino, Torino, Italy. Their first two children, Joseph Samuel, and Emanuel Philip were born in Ogden, Utah. They later moved to Oxford, Oneida, Idaho, where my father, Louis Paul Cardon, was born, March 17, 1868, [and] also a daughter, Isabella Susette, who died when about two years of age.

Again came a call from the Church to move to Arizona and help colonize there. In Arizona the company stopped on the Little Colorado, at Lake’s Camp, called Obed, a few miles south of Allen’s Camp, now called Joseph City. They cleared land and planted crops. Grandfather was a stone mason and bricklayer for the company.

A stone wall was built around the town, and nice buildings were erected. This was about 1875, that the call came from President Brigham Young. Grandfather Cardon had married in plural marriage and persecution was very bitter.

It was another trek after religious peace and into an unknown wilderness. The provisions they took and farm machinery were a great help. Part of the family had married and went with him, although a return trip was made to get the families of their son Joseph. They went to Arizona with the George Lake Company from Salt Lake City, crossing at Lee’s Ferry, and landing in Obed as noted. By the time all were together, Grandfather had decided it was too swampy, so arrangements were made to move to Woodruff. At Obed and Woodruff they lived in the United Order. It called for faith and sacrifices from the Cardons, as they had taken supplies for two years, and had many cattle, but they were willing to share with those less blessed who would have suffered without help.

After two years in Woodruff, the family moved to Taylor where they hoped to make a permanent home. Peace was not here for those of plural marriage, so in 1885, President Taylor advised Grandfather Cardon and his son Joseph, who had married into this order, to go to Old Mexico where the government had no objection to this practice. Now the family was divided. Grandfather and Grandmother Sarah, the son Joseph and his families, and Emanuel and his family went. Father and Grandmother Susette stayed in Taylor. In 1896, her son Louis, was called to Colonia Dublán, Chihuahua, Mexico, to teach in the Church school. Grandmother went with him, another move for her religion, and she joined her husband and the rest of the family there. They arrived there late in August 1897, and lived there until the exodus in 1912, when the Americans in the colonies were driven from their homes to El Paso, Texas. From there they went to Tucson, Arizona where she spent the remaining years of her life. She died July 18, 1923.[17]

Grandmother was very industrious and thrifty. Her family never wanted for food and clothing, although when small she did gather wool from thorns and bushes where sheep had gone through, dyed it, and spun it, then made their clothes. She used wild plants and indigo for coloring and the result was beautiful and durable. She also made blankets, and knitted some of these, as she did other articles of clothing. I remember her showing me her own dresses, up to fifty years old, that looked almost new. She wore these with an air of distinction, not looking old fashioned, but rather more like a Dresden china doll.

She was small, weighed not over a hundred pounds, not over five feet tall, with sparkling black eyes. In her youth her hair was brown. She was just a bundle of energy, with all this energy put into her work of the Church, which she held dear all her life, and also into the care of her family.

Susette Stale Cardon. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Susette Stale Cardon. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

She always had meats, vegetables, and fruits preserved but the strawberry was her specialty. She made a great deal of money in Idaho during the berry season from her small patch, serving strawberries and cream to the public. Again in Arizona she had her berries, and many a basket was given to those who had not, though she admired thrift in taking care of what one had. She dried great quantities, and took them with her on her journeys. When she left Mexico, she took some with her that had been dried in Idaho forty years before. The Economics Department of the University of Arizona asked for a sample of them. They said they had never heard of dried strawberries, much less of them being preserved to that age in a moth-infested country like Arizona and Mexico. They were still edible, but required airing away from the mothballs. A special treat in my childhood was some of her strawberry jam on pancakes.

Grandfather Cardon died in Mexico April 9, 1911, and when we were driven out, she [Grandmother] had accumulated quite a bit of property and money invested in the Union Mercantile store, which she lost. However, she showed her faith, even in leaving, since she had so many things in her home, and they could not be taken with her. Father told her he would take them and bury them, so maybe the rebels would not find them. Many people did this for the things that would not rot, and asked her why she did not. She replied simply, “No. They will not touch my things.”

Our home, being a large one, was stripped of all valuables, but when the first war storm had passed over, Joseph Elmer Cardon, her nephew, went back to Mexico to see if anything could be salvaged. He returned with a wagon load of her trunks of clothing, bed and table linen, and quantities of dried and preserved fruit. Her house, although unlocked, looked as though it had never been entered.

She loved the scriptures, and the hymns of the Church. After she came to America, President John Taylor gave her a hymn book written in French, and she obtained a Book of Mormon in French. She prized these very highly. Of course she had her childhood Bible also in French, and she read these all her life. She said she could understand her Bible so much better after reading the Book of Mormon.

Trials, like the song says, made her faith grow stronger, and her life was an inspiration to all who knew her.[18] She died July 18, 1923, age eighty-six, and was buried in the Binghampton Cemetery, just out of Tucson, Pima Co., Arizona.

The day she died she walked the short distance from her little home to our place, and stayed laughing and joking with my sister Florence and I. She ate dinner with us when the family came in. After the others left she laughed at us and told us how differently girls acted in her day, and dressed, also danced, and demonstrated the difference by dramatization until she was out of breath. After she had rested a few moments she started for home. She was still laughing but swayed slightly and caught the door frame to steady herself. We helped her to the bed, and my sister went after Father, Louis Paul, as we could see it was serious when she began to talk French and couldn’t remember her English. In a few hours it was over, so her wish never to be a burden on her loved ones came true. She was praying in French, her childhood language, and when the shadows of life’s evening closed she prayed as she did at the close of day, every day of her life, aloud in French, before going to rest, to arise refreshed to meet the dawning of another glorious morning, only this next arising the shadows will be dispelled throughout eternity.

Ellis and Boone:

When William Mulder was writing about Scandinavian immigration to Zion, he devoted one chapter to spoken language. He wrote, “For the Mormon immigrant, the break with the Old World was a compound fracture, a break with the old church and with the old country. . . . The new church was an American church interested in unifying the brotherhood, not in perpetuating backward-glancing cultural differences. . . . It is not surprising that in Utah the mother tongue died out quickly. . . . Elsewhere in the United States, in communities of Scandinavian and German Lutherans, for example, the church as part of the old Establishment performed an exactly opposite function: it strengthened ties with the homeland; it was a flame keeping warm the old language, the old faith, and the old customs through religious services and newspapers and denominational schools in the mother tongue.”[19] In Utah, English became the uniting language, both in congregations and in marriages where the partners were sometimes from different countries.

But this did not mean that immigrants forgot their native languages. As was noted for Cardon, she treasured her French scriptures and usually read them rather than an English version. She loved her French hymnbook and said her prayers each night in French. Finally, in the last hours of her life, she was speaking exclusively in the language of her childhood. Susette Cardon brought a little of the French language to Arizona when she made it her home after leaving Mexico.

Hannah Christina Bjorkman Chlarson

Albert Chlarson

Maiden Name: Hannah Christina Bjorkman

Birth: October 22, 1850; Malmaland, Sweden

Parents: John Gabriel Bjorkman[20] and Anna Christine Hanson

Marriage: Hans Nadrian Chlarson (or Nilsson);[21] January 17, 1884

Children: Frank (1884), Albert (1886)

Death: December 7, 1932; Tempe, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

My mother, Hannah Christina Bjorkman, was born in Malmaland, Sweden, on October 22, 1850. She was raised in the Lutheran faith until she was twenty-six years old, at that time she met the Latter-day Saint missionaries and heard their message; she was converted and joined the Church. Her family, friends, and even her sweetheart turned against her; she was cast out and disowned.

In 1880 she emigrated to the United States and then came out to Utah. She met and married, Hans Nadrian Chlarson, in January 1884. Two children were born to this union, Frank on December 26, 1884, and Albert on October 29, 1886. They came to Arizona in 1886 where my father engaged in farming for a time, then he went into the saw mill business.

My mother remained faithful to her church throughout her life. At one time her bishop said of her that she was one of the most faithful tithe payers in the ward. She was a Relief Society teacher and attended Relief Society regularly. She never heard from her folks or friends. She passed away at my home on December 7, 1932, at the age of eighty-two. At that time we were living in Tempe, Arizona. We laid her to rest in Thatcher.

When I was a young man, we lived close to President Andrew Kimball, Spencer Kimball’s father.[22] My mother and I were coming home one evening just about dark. Spencer was milking the cows and singing at the top of his voice. My mother stopped dead still for a few seconds and then she said, “That boy will one day be an Apostle of the Lord.” We walked perhaps twenty feet farther, she stopped again, this time she seemed to be out of breath. She raised both her hands and looked up and said, “Yea! And he might even live to lead this Church.”

Ellis and Boone:

It is significant that Albert Chlarson chose to emphasize the story about Spencer W. Kimball when writing about his mother. The citizens of the Gila Valley, and indeed all of Arizona, were thrilled to have an Arizonan Apostle and later President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Evan Tye Peterson, when writing about the history of the Mesa Arizona Temple, said:

For many Arizona natives who are members of the Church President Kimball is one of their own, the first Arizonan to serve as President of the Church. Arizonans always claimed him and he always claimed them. However, more realistically, in his inspired perspective, he was a prophet for all regardless of their geographic allegiances. In point of fact, he was born in Salt Lake City and did not come to Thatcher, Arizona, until he was three years of age. When he was called to the apostleship, at the age of forty-eight, he moved to Utah. Yet he retained his love for Arizona. One General Authority, a person who was reared in Arizona, once asked him if it would be possible for him to fill his Church assignment and live in Arizona. President Kimball’s answer was, “If that were possible, I would be the first to go.”[23]

Hans Chlarson was a polygamist. His household in the 1880 census in Utah consisted of four wives and eleven children, but not all of his wives permanently located in Arizona. Christina was his fifth wife. By 1910, Hans and three of his wives lived in Thatcher. Each wife lived separately, and Christina lived only a few doors down from Spencer W. Kimball.

The 1910 Old Folks Party photograph, W. W. Pace Home; front row, left to right: Ann Pace, Celia Chlarson, Phebe Fife, Hannah Chlarson, Samuel Claridge, Rebecca Claridge, Lora Ann Brown, Harriet and Marion Montierth; back row: Mrs. H. H. Romney, Elizabeth Pace, Cynthia Layton, Mary Ann Hoopes, Erastus and Julia Carpenter, Ella Brinkerhoff, Emma B. Coleman, Maud Callison, Christina Chlarson, Isaac Robinson, Laura Barney, Katherine Pace, Louise Hamblin, Sarah Jane Lewis, Erastus and Maria Wakefield; child in front: Roy Pace. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

The 1910 Old Folks Party photograph, W. W. Pace Home; front row, left to right: Ann Pace, Celia Chlarson, Phebe Fife, Hannah Chlarson, Samuel Claridge, Rebecca Claridge, Lora Ann Brown, Harriet and Marion Montierth; back row: Mrs. H. H. Romney, Elizabeth Pace, Cynthia Layton, Mary Ann Hoopes, Erastus and Julia Carpenter, Ella Brinkerhoff, Emma B. Coleman, Maud Callison, Christina Chlarson, Isaac Robinson, Laura Barney, Katherine Pace, Louise Hamblin, Sarah Jane Lewis, Erastus and Maria Wakefield; child in front: Roy Pace. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

In the census records, Hans Chlarson gradually changed from listing his occupation as photographer (1870), to artist and farmer (1880), and sawmill owner (1900), with five of his sons working as loggers or in the mill.[24] In early Arizona history, the name Chlarson is synonymous with sawmilling. Hans’s son Hyrum first moved the Chlarson sawmill to Crooks Canyon, two times further up the mountain, and finally moved it to Show Low.[25]

To summarize Christina Chlarson’s life, however, this 1927 description of her comes via Ryder Ridgway. In 1977, he wrote a newspaper column which described a 1910 photograph from Thatcher: “From the goodness of their hearts and over a period of many years, Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Pace would invite Thatcher area pioneers into their home for heartwarming reunions. Over tables piled high with delicious foods the oldsters would reminisce about days of yore, sing songs of yesterday [and] among other things, have their likenesses recorded for posterity.” Earlier, in 1927, W. W. Pace had sent the 1910 photograph to the Arizona Republican and described each person. Of Christina Chlarson, he wrote, “Next, Christina Chlarson, who still lives and is as energetic as a woman of half her age. She really has made two blades of grass grow where none grew before, one of the most energetic, industrious women we have ever known.”[26]

Julia Ann Holladay Clark

Unidentified Descendant

Maiden Name: Julia Ann Holladay

Birth: January 4, 1862; Spring Lake, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: Thomas Wiley Middleton Holladay and Ann Horton Matthews[27]

Marriage: William Ashby Clark; January 21, 1878

Children: William Thomas (1879), George Wiley (1882), Minnie Ann (1883), Edward Watkins (1886), Maud Elizabeth (1889), Delbert Ashby (1893), Nevert Leroy (1894), Lois Julia (1896), Elora Phoebe (1900), Vernal Hollis (1902), Millie May (1905)

Death: August 1, 1926; Los Angeles, Los Angeles Co., California

Burial: Inglewood Park Cemetery, Inglewood, Los Angeles Co., California

Julia Ann Holladay was born January 4, 1862, the fourth child of Thomas Wiley Middleton Holladay, born September 2, 1836, in Marion County, Alabama, and Ann Horton Matthews born December 15, 1838, daughter of Joseph Lazarus Matthews and Rhoda Carroll.

Julia Ann’s father came into Salt Lake Valley a boy of eleven years, with his parents, John Holladay and Catherine Beasley Higgins, six sisters and three brothers. They settled on Cottonwood Creek, which became Holladay, Utah. He had the honor of bringing the first forty pounds of turkey hard wheat for seed from which all the mountain states have obtained their seed.[28] These people were converts from Alabama and arrived in Salt Lake Valley a few days after Brigham Young’s first company.

Julia Ann’s grandfather, Joseph Lazarus Matthews, was one of Brigham Young’s scouts who preceded him into Salt Lake Valley by two days. The company with Brigham Young arrived July 24, 1847. He [Joseph] left his wife, Rhoda Carroll, and three little girls at Winter Quarters with the Saints (Mormons). He, with others including Brigham Young, returned to Winter Quarters and brought their families [west] in 1848.[29] His name is on the “This is the Place” Monument, built to honor the first Pioneers of Utah.

Both of Julia Ann’s grandparents, John Holladay and Joseph Matthews, were called, with other Saints, by Brigham Young to settle San Bernardino, California, in 1851. This was known as the “Charles C. Rich and Amasa Lyman Company.”[30] Thomas Wiley Middleton Holladay and Ann Horton Matthews were young people and married in San Bernardino April 1, 1856, a year before the Saints were called from there back to Utah by Brigham Young due to troubles of the Mountain Meadow Massacre and other reasons.[31]

On returning from San Bernardino these families settled in Santaquin, Utah County, Utah. Julia Ann was born in Spring Lake near Santaquin. Here she grew up as a child, suffering the trials and hardships of pioneer life. Being a “good worker,” she learned to knit stockings when very young. At the age of ten she was invited to the grownup quilting bees “because she was a good little quilter.” Later in life she quilted at Relief Society and taught her daughters and others the art. She was a good cook, making the best mince pies, head cheese, biscuits, etc., and at church socials and picnic dinners her pies and homemade bread were always welcomed.[32]

Nursing was her second nature, and she was happy relieving others of their aches and pains. A dreadful thing happened when she was about twelve years old. Her little sister, Henrietta Caroline, started to build a fire in the kitchen stove with coal oil. It exploded and burned her severely. Her mother, who was in bed with a tiny baby, hurriedly rushed in with her bed clothing and smothered out the fire and saved the child. Julia Ann heard the screams and came running. Her mother’s hands were so badly burned that for weeks she had to assist her mother by taking out her breast for the baby to nurse. Henrietta’s hands and face were scarred and to protect her poor burned eyes she wore a bonnet always. She lived to be the mother of thirteen children and was a favorite of her loved ones.

One of the neighbors of the Holladay family in Santaquin was the Edward Watkins Clark family who came to the Valley in 1852. They were converts to the Latter-day Saint Church in England in 1847. He [Edward] was born June 6, 1820, in Pattingham, Staffordshire, son of James Clark and Phoebe Ransford. His wife, Lucy Ashby, was born December 14, 1818, in Millend Harts, England, daughter of William Ashby and Elizabeth Grimsdale. They, Edward Watkins and Lucy Ashby Clark, settled first in Provo where their son, William Ashby Clark, was born May 1, 1855. Their old home is still standing in Santaquin (1958) where Julia Ann and William Ashby had their courtship.

Julia Ann Holladay Clark. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Julia Ann Holladay Clark. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

She said he used to haul her around the streets in a little red wagon when she was a little tot. He was seven years older than she. He grew up and worked with the cattle up in Montana, later coming back home and falling in love with her. William’s parents are buried in Santaquin and Julia Ann’s parents are buried in Pima, Arizona, but her grandparents, John D. Holladay and Catherine Beasley Higgins, are buried out from Santaquin on their original acreage of 640 acres that they had for their farm and home.

William and Julia Ann’s first child, William Thomas, was born April 26, 1879, in Payson, Utah. They went to Salt Lake City and were sealed for time and eternity in the old Endowment House September 18, 1879. Soon after this, they joined the company that was called by the Church Authorities to settle in Gila Valley, Arizona. Her grandfather, Joseph Matthews’ family, her father and mother, and all her brothers and sisters, save one (George Holladay, who married Alveretta Jones and remained in Salt Lake City) went to Arizona.

These families were experienced pioneers, but with their oxen, horses, cattle, covered wagons, and supplies, they experienced many hardships traveling through southern Utah and northern Arizona. They had to carry water for themselves and cattle and horses. It took them three months to complete the journey. They had to ford the Colorado River. Even at this time, Indians were hostile, and fear of them was constantly on their minds, especially Julia Ann with her young baby. She always said she started to Arizona with her baby and an old iron stove in the wagon.

These families settled along the Gila River in Graham County, Arizona, first at Smithville, later called Pima, almost in the shadows of Mount Graham. The Matthews families and others settled down the valley a few miles and named the place Matthewsville, later changed to Glenbar. Anyone raised in the Gila Valley knows how high, wide, and handsome the mesquite trees grow. Here at Smithville the people all got their water from the town well in the midst of these mesquites. It was raw land indeed. Here everyone came for water for home use and to water their stock and to exchange news. They had what they called “lizard trails” from their camp to the well. The “lizard” being a green forked mesquite limb on which were fastened their water barrels with rawhide thongs. They pulled this limb with a horse. Julia Ann rode with her baby many times on the lizard to meet her neighbors at the well and obtain drinking water.

The town Smithville, later Pima, after the Pima Indians, was patterned after Salt Lake City—wide streets, big blocks, and large lots for each family. The men drew their lots for their home place. The fields were out by the river where they could obtain irrigation water.

The hardships of these dear Pioneers were many, hewing down mesquites, clearing the sagebrush, making dams in the old Gila River, and digging long canals to carry the precious water to their small farms. About the time they got a good dam built, with water coming and growing crops, the river would go on a rampage from hard rains in the mountains and wash out the dam, change its course, and leave some poor farmers with acreless land which became worthless river bottom.

Shortly after their son George Wiley was born February 18, 1882, in Pima, Julia Ann and William Ashby sold their home in Pima and moved with their family to a homestead on the north side of the river across from Matthewsville. Their first home was a one-room adobe house, the roof being built of limbs and dirt. An additional room was constructed of willows and mud, built Indian style with dirt floor. Julia Ann prided herself in keeping these dirt floors hard with water and swept them daily. Here she lived and gave birth to Minnie Ann, born November 8, 1883; Edward Watkins, born March 10, 1886; Maud Elizabeth, born January 5, 1889; two boys, Nevert Leroy and Delbert Ashby, who died in infancy; and Lois Julia, born November 28, 1896, also born in this pioneer home.

During this time on the farm in Eden, Arizona, they raised many cattle, hogs, and grain crops—wheat, corn, sorghum cane, and vegetables. In the winter time, William worked with his teams and wagon, freighting from the end of the railroad in Bowie to the copper mines in Globe, Arizona. This was very dangerous, due to the hostility of the Indians. It was a constant worry to Julia Ann when William was away. Many Indians were killed by these freighters in these days.[33] Once they got a wagon full of ladies’ hats and scattered them all over the desert.

All the people who lived in Eden had to haul their drinking water from a clear cool spring some five miles out in the hills. They used the river or canal water for other purposes and to clear it, stirred it up with long sticks and put a beaten egg in it. Julia Ann also made her lye for soap from wood ashes. She colored flour sacks for children’s clothing and quilt linings with chaparral or sour dock roots. The children would gather wild sour dock in the spring for “rhubarb pies.” She was very proud of her bed ticks which she stuffed with the finest of corn shucks, saved while the family shucked corn for the hogs. She made beautiful white pillow shams and bed spreads embroidered in red thread.

Before 1900, William built them a lovely new brick home on the homestead. Julia Ann busied herself in making new homemade carpets from the children’s old clothes. Here her family enjoyed candy pulling parties, pets like a young fawn, and a black dog named Rover. Here two more children came to bless her home: Elora Phoebe, born February 14, 1900, and Vernal Hollis, born June 10, 1902. Her daughter Minnie Ann attended the Gila Academy, being one of the first students to attend after it was built in Thatcher, Arizona. While living here, her daughter Minnie was married and gave her two lovely grandchildren—a boy and a girl. The girl died, bringing grief to all.[34]

About 1903 William had begun prospecting. His land was all washed away by the river and the brick house was about three hundred feet from the river bed. He decided to move his family onto a rented farm in Fort Thomas. Here he did a lot of good farming. Here their last baby girl, Millie May, and their eleventh child was born April 29, 1905. She proved to be a great comfort to her mother in later years. While living here, their daughter Minnie died of typhoid and pneumonia in Pima, leaving her son to be raised by his father. He was buried in the river bank in a cave in—his neck was broken and when they found him he was dead.[35]

From Fort Thomas they moved to Eden again, but the river washed within a few feet of the house. At this time William sold one of his mining properties, the “Cobra Grande,” for enough money to buy a new house and farm in Pima. The entire family was joyous to make the move. They gave the Eden brick house to the Church and a tithing office was constructed of the brick. Julia Ann was especially happy because her mother and sisters were there. She always entertained the folks from across the river like they were her own when they were caught on her side of the high river. Here her family lived and were happy. Her daughter Maud married and after two children were born, came home to have her third while she worked. Her mother cared for the little ones, and they were like sisters and brothers to Julia Ann’s younger children.

World War I came and at that time Julia Ann had many problems of nursing whole families with the flu during the epidemic. Her own family all took a turn, and she kept going day and night. Her children were taught prayer by her. She seemed to breathe a prayer. She had a firm testimony of the gospel of Jesus Christ and always went to Church with her family and taught them to walk uprightly before the Lord. She was honored and loved dearly by her husband and children. She saved Sunday eggs for the building of the Arizona Temple[36], lived to see it built, but was very disappointed in not being able to attend the dedication.[37]

Her girls at home all attended the Gila Academy and received religious training there. Her daughter Julia married and moved to California. Elora finished school and taught many years in the Gila Valley and in Tucson. After Elora married, Millie went to Tucson to live with her. Julia Ann and William were homesick for their children so they sold the old home in Pima and moved to Los Angeles, California about 1923. They built themselves a nice house there within a few blocks of their daughter Julia. Her husband and Vernal and Millie helped them. They worked faithfully in the Church in Belvedere Gardens. They were all active in the Church and helped build the first church house of Belvedere Ward. This was the first ward in all of the mission of California.[38]

They enjoyed their lovely garden of vegetables and flowers. She [Julia Ann] had always wanted beautiful flowers. She enjoyed her grandchildren there and also visits from Elora and her baby from Tucson. Her sister Nora and other relatives lived there, and she was so in love with life. She got ill, and after a year’s time of serious illness, she grieved because she knew she had to leave us. Her baby girl, Millie, was not married at this time. Her son Vernal was the last to talk to her at midnight. She died August 1, 1926, and was buried among the beautiful flowers, at her request, in Inglewood Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.

Ellis and Boone:

William and Julia Clark’s move to California in 1923 was typical of many Arizonans. Although a few Latter-day Saints lived in California earlier, growth of the Church in California did not really begin until Joseph E. Robinson became president of the California Mission in 1901. After the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the mission home was changed from San Francisco to Los Angeles, where there were more members and a direct rail service to Utah.[39] Those portions of Arizona that were not part of a stake became part of the California Mission, meaning Tucson and sometimes St. David. President Robinson traveled to Arizona and organized the Binghampton Branch on May 22, 1910, and the branch at Pomerene on March 9, 1911; when Robinson came to Arizona, he would play the piano, sing, and speak. Originally, residents of Pomerene wanted their town named “Robinson,” but this was rejected by the post office.[40] While Robinson was mission president, the Adams Branch in Los Angeles was organized and the Adams Branch chapel (next to the mission home) was dedicated on May 4, 1913.

After eighteen years of service, Joseph Robinson was released, and Joseph W. McMurrin became president of the California Mission. As a young man, McMurrin had lived for a time in the Little Colorado River communities, so he was known to many in Arizona. He immediately began working toward having wards and stakes in California, and on January 21, 1923, the Los Angeles Stake was created and the Adams Ward organized on March 11. Within a year, twelve other wards were created in southern California, including the Belvedere Ward. Four years later, the stake’s membership had doubled and a second stake was created.[41]

Richard Cowan and William Homer wrote that “consistent with the Church’s progressive attitude [during the early part of the twentieth century], leaders continued to send clear signals that settlement in California would not only be condoned but encouraged.” Arizona pioneers moved to California a few at a time as it became obvious that many of the Mormon farming communities simply could not support the natural growth of large families.[42] In addition, after World War I Arizona’s farming and ranching economy struggled with drought and little market for cotton.[43] Cowan and Homer thought that Church members in general came to California for “advanced education, a mild climate, an interesting and stimulating culture, and the comparatively favorable salaries and working conditions.”[44] As demonstrated by the fact that some of William and Julia Clark’s children move to California first and then William and Julia followed in 1923, often family members simply wanted to be with loved ones. Many of Arizona’s pioneers eventually became modern pioneers to California.

Harriet Ann Bean Cluff

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Harriett Ann Bean

Birth: May 31, 1855; Provo, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: James Addison Bean and Harriet Catherine Fausett

Marriage: Orson Cluff; December 30, 1872

Children: Orson Leroy (1873), Abbie Nina (1875), Harvey Milton (1877), William Fairington (1879), James Addison (1882), Margaret Hilda (1885), George Leo (1887), Hattie Mae (1890), twins Vera and Vella (1894), Eva Irene (1895)

Death: April 16, 1931; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

James Addison Bean and his wife, Harriet Catherine Fausett, had been in their new home, the town of Provo, Utah, for a short while and were working hard to get the farm and orchard developed. In the spring of 1855 a new daughter, Harriet Ann made her appearance on May 31. She spent her childhood in the shadow of the beloved Timpanogos mountain, growing in body, mind, and spirit, next oldest to five sisters and six brothers.

In her youth she learned the art of spinning, weaving, and knitting, and used these arts in helping her mother make clothing for the younger children. She also learned to make candles and to make soap from the scraps of fat not used for food. She was a good cook and learned to make delicious dishes from the materials they had. One winter before the sugar factories were brought into that valley, sugar and honey were scarce, but they had had a bounteous harvest of squash. Freezing the squash turned the liquid very sweet, so she and her mother cut squashes and put them out on the snow to freeze. Then they put them in pans in the house to thaw. The juice which drained from them was boiled down to a syrup, and this was used to sweeten their pies, to make pumpkin butter which was used as a spread for their bread, and to make other desserts.

Harriet Ann Bean Cluff. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Harriet Ann Bean Cluff. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Her father later raised delicious fruits and Hattie, as she was lovingly called, learned methods of preserving a supply for use through the long cold winters. Apples and peaches were dried; hams and bacon were smoked and hung in the smoke house. Beef and venison were scalded and dried into jerky (strips of flavorful dried meats which kept through warm or cold weather).

President Young had seen to it that Provo had schools established, and Hattie attended whenever she was free from home duties. She loved to recite poetry and give readings. This was an art often used for public entertainment in those days when people had to provide all of the pastime activities and social performances.

Dancing parties and candy pulls were popular among the young folks. Among her acquaintances was a young man who also delighted in giving dramatic readings, and who excelled in dramatics and took part in all the plays. He was a neighbor, Orson Cluff. These two found enjoyment in their mutual interest and soon fell in love. They were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City on December 30, 1872.

Hattie kept busy for months before her wedding working on her trousseau. She spun the thread and wove the cloth for her linens and house dresses, and made quilts from the scraps. The cloth for her wedding dress and temple clothes was purchased from the store in the city.

After their marriage the young couple moved to Coleville where Orson found employment. The house that they moved into was infested with bedbugs, and they could hardly sleep. Since there were no known poisons for pests in those days Orson stretched a sheet above the bed. As the bugs came out of hiding they fell onto the sheet, and by this means he was able to do away with many of the miserable pests. So they were able to get a little sleep. The next day Hattie went over the house and filled in all the holes that she could find, and lighted a caustic stick which she let burn all day. That got rid of the bedbugs for the remainder of the time that they lived in that house.[45]

They moved back to Provo soon after their first born, Orson Leroy, was born. While here two more children came to bless their home, Abbie Nina and Harvey Milton. There was a call from President Young for young couples to help settle the wild new Arizona territory. Orson moved his little family to a small community of Forestdale which was a few miles west of Show Low camp. There were many wild animals, deer, porcupines, skunks, etc., which ate on their crops. Wild [mountain] lions and panthers sometimes frightened their cattle and horses. And the Apache Indians were not friendly. They were near the reservation line. The Indians pestered them a lot hoping to drive them to move out of the area.

The house had no windows in the openings, and Hattie was frightened of Indians since there had been wagon trains burned by these marauders. One day the horses wandered off. Orson went out to follow their tracks, which led to Show Low camp.

He asked a neighbor boy to go over to stay with Hattie until he returned. But the boy did not come so Hattie hung quilts up to the openings and pulled the cupboard in front of the door and stacked trunks and boxes filled with goods against the openings, then walked the floor all night listening to the prowlers outside with fear of being molested any minute.

After dark came upon Orson, he was quite certain that his team had gone back to the Show Low ranch, where they had been accustomed to being, so he continued to walk along the trail through the thick timber over the hills. As he walked he could hear the pat of steps behind him. When he became very nervous he stopped, turned, and lighted a match and the light reflected into two large yellow eyes. Having no gun or knife with him he was forced to travel on. The animal continued to follow him right up to the door of his relatives who lived at the ranch. The next day they saw many very large cat tracks in the door yard.

Cluff family about 1923; (adults form left) Harriet Ann Bean Cluff, Merintha Loveridge Cluff (second wife), Orson Cluf, Mary E. W. Cluff Haymore (widow of Harriet's son, Orson LeRoy), Orson LeRoy Cluff Jr., and his wife Helen Loving Cluff; (children from left) Ellen Haymore (youngest daughter of Mary Wilson Cluff Haymore), Rose, Ivan, and baby Harold (children of LeRoy and Helen). Photo courtesy of Ron Haymore.

Cluff family about 1923; (adults form left) Harriet Ann Bean Cluff, Merintha Loveridge Cluff (second wife), Orson Cluf, Mary E. W. Cluff Haymore (widow of Harriet's son, Orson LeRoy), Orson LeRoy Cluff Jr., and his wife Helen Loving Cluff; (children from left) Ellen Haymore (youngest daughter of Mary Wilson Cluff Haymore), Rose, Ivan, and baby Harold (children of LeRoy and Helen). Photo courtesy of Ron Haymore.

When the government moved the reservation lines out, which included Forestdale in the Indian reserve, the Cluffs and their neighbors, the Wests, Adams, Lundquists, Farleys, Frisbys and Nuttalls, were forced to go elsewhere to make their homes.[46] Most of them decided to go into the Gila Valley. They were followed for the first few days by a band of Apache braves. Under these trying circumstances, they felt very humble and solicited the Lord’s protection on their travels. After making camp and settling the children in their beds, the men built a big bonfire. They sang and told stories, and before retiring one of the men was asked to pray; he stood beside the fire, raised his arms to the heavens (as preachers used to do), and asked the Lord to protect them from the Apache molestations. The Indians slinked off into the night and the travelers went in peace.

About thirty years later one of the men, who knew of this incident, related it to an old Indian friend. The old man told him that he was one of the young braves who was following the Mormons, and when they saw the man talk to the Great Spirit, they left not wanting to interfere.

As her family married and began to have families of their own, Hattie’s heart was made sad by the early death of her oldest son Leroy, whose first child was but three years old.[47] A few short years later her oldest daughter, Nina, passed away with pneumonia leaving five young children.[48]

Harriet Ann Bean and Orson Cluff in her garden (note trellis for beans) at "Grandma Cluff's house" in Pima. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Harriet Ann Bean and Orson Cluff in her garden (note trellis for beans) at "Grandma Cluff's house" in Pima. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Hattie took the younger boy, Hartley, who was three years old, and with her daughter Eva went back to Utah to care for her aged father in his last days.[49] Through all her trials and sorrow, Hattie remained faithful and true to her faith.

After her father passed away she and Eva went to Pima, Arizona, and made their home. Eva married Wallace Taylor of that town, and they built a home next to her mother so Hattie enjoyed this family of grandchildren; though the others lived some distance away, she visited them periodically.

Loved by all her neighbors and friends, she [Hattie] passed away April 16, 1931, at Pima.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch for Harriet Ann Bean Cluff includes very little information about her life after coming to Arizona, which also included living in Mexico. Orson Cluff married a second wife, Merintha Altheria Loveridge, in 1890 at Colonia Juárez, Mexico. She was twenty years younger than Harriet, and both Harriet and Merintha had children born in Mexico. The Cluff family also lived at Colonia Garcia.

After leaving Mexico during the revolutionary unrest of 1912, the Cluff family lived for some time in Utah; the last child of Orson and Merintha was born in November 1912 in Salt Lake City, and Harriet’s mother died in Provo that same month. By 1920, Harriet was living in Pima with her son James Addison and his family; Orson and Merintha cannot be located and so are assumed to be living in Mexico at that time. By 1930, Orson and Merintha were living at Alma, Maricopa County, and Harriet was living alone in Pima. In 1931, Harriet died and was buried in Pima; on her death certificate she is listed as a widow. Orson died two years later and was buried in the Mesa Cemetery. Merintha lived another twenty years and is also buried in Mesa.

With Harriet living in Pima (Graham County) and Merintha living in Alma (Maricopa County), the Orson Cluff family illustrates one of the choices polygamists made to live separately after coming out of Mexico. It was common for a woman to report herself a widow in federal censuses (even though her husband was still alive) if they were not living together. Nevertheless, these two informal photographs from the 1920s illustrate that Harriet and Orson Cluff maintained some contact during this period.

Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross

Author Unknown[50]

Maiden Name: Louisa Gulbrandsen[51]

Birth: November 27, 1850; Asser Precinct, Christiana, Norway

Parents: Hans Gulbrandsen and Ellen Poulsen

Marriage: David Eugene Cross; February 28, 1870

Children: William Benjamin (1870), Mary Ellen (1873), Florence Pearl (1875), Cora Louise (1877)

Death: March 24, 1936; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Louisa was born November 27, 1850, in Asker, Norway, the daughter of Hans Gulbrandsen and Ellen Poulsen. She had two sisters and one brother: Paulina Augusta, Mathia, and Bernhard, but only Paulina (Lena) Coombs lived to adulthood.

Her mother died in 1858, and then her father married Anna Marie Andersen.[52] The family embraced the gospel in 1860, and in May of 1863, they set sail for America in the ship Excellent No. 12 arriving in New York, the latter part of June. They were about six weeks on the water.

She [Louisa] was terribly seasick and, in trying to get to the railing one day, a man stepped in front of her and she spewed down the front of his fancy white shirt. They crossed the Plains with ox carts in Captain Nebeker’s Company, arriving in American Fork, Utah, in October 1863.

On February 28, 1869, she was married to David Eugene Cross in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City by Daniel H. Wells.[53] She would not marry anyone outside the Church, so he joined it to get her. They moved to Fountain Green, Utah, where three children were born to them; William Benjamin, Mary Ellen (Nellie) and Florence Pearl.

In 1875 they moved to Freeport, Illinois where another little girl, Cora, was born. David became conductor on the C[hicago,] M[ilwaukee], and St. Paul Railroad. They had a lovely home with imported carpets, oil paintings, marble topped furniture, a black walnut piano, etc. Everything was the very best, but he forced her and the children to leave their church and join his—the Lutheran Church.[54]

One morning in March 1885, he left home on his regular run on the railroad but failed to return. He completely disappeared. She advertised in the papers and wrote to old friends every where but could find no trace of him, and meanwhile, his brother Charles was helping to support the family. [55] She finally sold her home and furnishings, all but a few choice paintings and the piano, and went west to Woodruff, Arizona where her father and step-mother lived.

She settled her little family in one room of the old adobe fort with her father to keep an eye on them and went to Holbrook to find work to support them. The fort leaked so badly their clothes, bedding, and piano were nearly ruined, and the citizens of Woodruff refused to associate with the new “gentile” family from the city.

Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross with her children just before leaving Freeport, Illinois in 1886. Children standing: Mary Ellen (Nellie) and Bill; seated: Pearl (left) and Cora. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross with her children just before leaving Freeport, Illinois in 1886. Children standing: Mary Ellen (Nellie) and Bill; seated: Pearl (left) and Cora. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Conditions got so bad for her children that Louisa went back there and moved them into a “rock” house she rented. She then went back to Holbrook where she worked in hotels or took in washing—anything to make an honest living. The Woodruff people still mistreated the youngsters, so they were all re-baptized into the Church. A few months later, they decided they needed a new church building; instead of going to the hills for the rock, the townspeople put the Cross children out of their house and tore it down.

The mail driver took the news to Louisa so she returned in the night on the buckboard to see for herself. She went to the bishop and told him what she thought of him and predicted the building would never be finished. As late as 1909, the foundation still lay unfinished.

She took her family away from Woodruff at that time and boarded them with other LDS families. Will went to Holbrook and Pinetop to work; Nellie lived with and worked for the Albert Minnerlys in Snowflake; Pearl lived with Mr. and Mrs. Joe Bargeman in Holbrook and then with a school teacher named Webb; and Cora with Bishop James Owens of Woodruff and later his son Clark Owens, until the children all married one by one.[56]

Louisa continued to work in Holbrook in the winter time, but in the summer she would go from one daughter’s home to the other and sew carpet rags, piece quilts, and make soap.

In spite of working hard, she enjoyed life. She had a jolly, sunny disposition and was always ready to laugh or to dance. Most of the cowboys in the country would tell you that she taught them how to dance.

When the Clarks gave up the Hotel where Louisa worked, they insisted she make her home with them, which she did, until Mrs. Clark passed away. Louisa then lived with Nellie’s family in Snowflake until long after Nellie’s death in 1927, when she moved to Joseph City and lived with Cora.

When Pearl returned to Snowflake from Oregon, she took care of her mother until she [Louisa] passed away March 24, 1936. She would have been eighty-six years old had she lived until November of that year.

Ellis and Boone:

Information in this sketch may be more problematic than any other sketch in PWA, but the errors did not come from Clayton. She received this sketch from Louisa’s granddaughter, Hattie Miller, after most of the book was typed.[57] Therefore, it is found at the end of the book rather than in alphabetical order.

This story of Louisa’s life is a sanitized version written for grandchildren and the general public.[58] Adults in the family often discussed other versions among themselves. During his lifetime, David Cross sometimes lied about his age and used several different aliases. When he and Louisa were married in the Endowment House, he was using the name of Bradley Wellington Wilson because he had deserted from the army in Utah.[59] After moving his family back to Illinois, he deserted them and assumed the name of David Robert White.[60]

Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross, about 1920, at the home of her daughter Nellie Hunt in Snowflake. Photo courtesy of Ruby Gibson Collection, Catherine H. Ellis.

Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross, about 1920, at the home of her daughter Nellie Hunt in Snowflake. Photo courtesy of Ruby Gibson Collection, Catherine H. Ellis.

This sketch illustrates many of the problems common in historical and genealogical research. Misinformation about the immigrant trip to Utah may have arisen from Norwegian-English language problems. Hans Gulbrandsen was a watchmaker and borrowed $376 from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund to finance the trip. The family may have traveled from Oslo to Liverpool on a Swedish steamship, the Excellencen Toll, but they crossed the Atlantic Ocean on the packet ship Antarctic arriving at Castle Garden, New York, on July 10, 1863. Then they traveled by train from New York City to Florence, Nebraska, and became part of the Peter Nebeker wagon company. This was the Fourth Church Train in 1863; the company left Nebraska on July 25 and arrived in Salt Lake City on September 24.[61]

Eventually, Louisa, believing she was a widow, applied for a pension based on David’s military service (Civil War and service in Utah). She first applied in 1908, was rejected because she could not prove David’s death, and then reapplied in 1923 after the pension laws were liberalized. Many of the unsavory aspects of David’s life surfaced during the application process, but papers in the file (covering fifteen years) show that Louisa was held in high esteem by people from Arizona, Utah, Nebraska, and Illinois. Even the pension examiners considered her deserving, although at first they questioned whether or not she was telling the truth. In 1923, the special examiner wrote, “I am satisfied that she did not intentionally conceal the fact that [the] soldier was financially involved at the time he left Freeport, Ill. in 1885.” In conclusion, he also said, “The claimant is well known and enjoys a splendid reputation at Snowflake, Ariz. where she has lived for more than 30 years. Every one of whom inquiry was made spoke of her in the highest terms.”[62]

Sarah Diantha Gardner Curtis

Olive Kimball Mitchell[63]

Maiden Name: Sarah Diantha Gardner

Birth: September 9, 1852; Payson, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: Elias Gardner and Diantha Hanchett

Marriage: Joseph Nahum Curtis; January 17, 1870

Children: Sarah Diantha (1871), Charlotte Iris (1873), Lillie (1874), Florence (1876), Chloe (1879), Joseph Naham (1881), Milton (1884), Erastus (1886), Elsie Luella (1887), Clara Edna (1890), Nora Visalia (1892), William Warren Elias (1894)

Death: April 5, 1942; Tucson, Pima Co., Arizona

Burial: St. David, Cochise Co., Arizona

Sarah Diantha Gardner was born September 9, 1852, in Payson, Utah. Her parents were Elias Gardner and Diantha Hanchett Gardner. She was a strong, healthy child and very industrious. She loved whatever work she had to do. Sarah, or Sadie as she so often was called, attended school in Payson until about the age of thirteen, then her father moved to Richfield where he had a store and a sawmill. She helped in the store and at many little jobs. At nursing and baby-tending, she was kind and capable. As a young lady, she was one of the first teachers in Payson and Salem, Utah.

The family was in Richfield when the Black Hawk War broke out in that area. She met Joseph Nahum Curtis, who fought in this war. Sadie helped her mother make crackers and helped her father dry meat for these soldiers. She saw many scenes of torture and savagery.

Joseph Nahum Curtis of Salem, Utah was nicknamed “Dode” by many friends and relatives. He fell in love with Sarah Diantha; they had a short courtship and were married in the old Endowment House in Salt Lake City, January 17, 1870. After the wedding, they returned to Salem where they built their home and where their first five children were born. They were very active in Church affairs. On November 20, 1870, at a general meeting of town folks, Eliza R. Snow proceeded with the organization of a Primary Association, and after her preliminary remarks she paused, and pointing down into the audience, she said, “There is the president of our organization.” Then she said, “Please stand up.” Sarah Diantha Curtis was the woman chosen as the first Primary president of this new ward. Sister Snow had been given the power to select the person whom God thought would make this Primary organization a success.[64]

President Brigham Young had foreseen the rapid influx of converts to the Church, and many people, among them Joseph Nahum Curtis, were called by President Young to go to Arizona and to investigate the opportunities to settle in this new land.

Before leaving for Arizona, Joseph N. Curtis married his plural wife, Marilla Gardner, a sister to Sarah, on March 24, 1881. This was a happy marriage as all were united together.

It was April 18, 1881, when they left their comfortable little home in Salem, Utah. Dode’s brother, William Curtis, and other families traveled along with them. They took three months to make the trip. When they reached the Colorado River at [the] place that is called Lee’s Ferry, a short distance south of the Utah border [but] in Arizona, they found the river raging with flood [waters] and badly swollen. A delay of some ten days was incurred. They had to take the wagons apart and take them over in small boats and swim all their livestock, which was a treacherous undertaking, but successfully done. When the families and their possessions were across, they re-shod the mules, horses, cows, and oxen.[65] They did baking, washing, and mending and all repairs and finally got on their way, still bearing south over a dreary desert for miles without much grass or trees and only an occasional water hole.

Sarah Diantha Gardner Curtis. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Sarah Diantha Gardner Curtis. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Due to the rocky road and dead ax wagons, Sadie had to ride a mule most of the way over the Buckskin Mountains and Lee’s Backbone mountain in order that she might protect her unborn child.[66] This was her sixth child. The trip was long and painful for her. The going was rough, the cows and horses had to be shod several times as their feet and legs were sore and bleeding from the sharp rocks along this mountain road. It is hard to understand how such people could leave their comfortable homes and a way to provide for their loved ones, to go through so much difficulty in order to reach a place they knew nothing about, all because their Church Authorities had told them to do so, and they wished to obey. They didn’t think of turning back; they simply plodded on and made the best of their troubles. As they wandered, they passed through small settlements and outposts along the way, such as Joseph City, Flagstaff, Concho, Fort Apache, and on down to the Gila River, Rice, San Carlos and finally reaching a small colony of Mormons at Pima, Arizona where they rested a few days, then on south they went, past the Graham Mountains, near Fort Grant, in the Sulphur Spring Valley, over Dragoon Pass, then down to the San Pedro River, at St. David, where they arrived June 16, 1881.[67] They took refuge in the shade of a huge mesquite tree and stretched a tent for a house. While living under this tent and tree, Sadie’s first son was born. His name was Joseph N. Curtis Jr., commonly called Jody. He was born August 5, 1881, about two months after their arrival.

The Apache Kid, an Indian, was on the warpath and sometimes raided the flocks and herds of the people. So at night they would sleep in a rock fort built by the settlers for protection. This was the time of the great Indian trouble with Chief Cochise and Geronimo.

The following September 12, the ladies of the colony met in the house of Philemon Merrill, who was presiding over this colony, and organized the YLMIA. Sarah Curtis was chosen as president, with Emma Merrill first counselor, Lucy Ann Merrill second counselor, and Hulda Hubbard secretary.[68]

In April 1882, Joseph had built a small adobe house for better shelter. On May 1, 1882, Marilla gave birth to her first child, whom they named Marilla May. Marilla was not long with this family. She had five little girls and with the fifth one she was called to the other side and so Sarah raised the five girls as her own.[69]

On February 25, 1883, when the General Authorities had chosen Christopher Layton, who also came from Utah, to be president of the stake, which was then called St. Joseph Stake with headquarters in St. David, quoting Sarah, “I was released from Ward YLMIA and chosen to be president of stake YLMIA by President Christopher Layton. Laura Nuttall was first counselor, Rhoda Foster second counselor and Sarah Burns as secretary.”[70]

After a period of time, President Layton moved to Thatcher and the headquarters of the stake was moved there which made 120 miles for Sarah Curtis to travel by team and buggy to her board meetings and conferences, always taking two or three little children along. On March 22, 1888, Sarah resigned her position because of the hostile Indians and dangerous conditions and Laura Nuttall took her place as president.

It was in 1883 that Joseph (Dode) filed on a homestead of 160 acres, about six miles south of present St. David. Joseph was asked to leave the St. David country to go to Thatcher to live, but he could see that, in this fast growing part of St. David, he could do better by his family, so they lived there on this once beautiful homestead until their deaths.[71]

On August 18, 1889, the YLMIA was organized under Bishop Peter A. Lofgreen[72] of the St. David Ward. Sarah was again put in as president. On February 10, 1898, she was released from MIA and sustained as first counselor to Margaret Goodman in the Relief Society.[73] In January 1899, the St. David Ward was divided and Sarah was sustained president of Relief Society in the new San Pedro Branch of the St. David Ward of the California Mission. She remained in this position until the ward disintegrated. The people of the San Pedro Ward, commonly called Curtis Ranch, moved away on account of scarcity of water. Joseph Nahum Curtis was the bishop of the San Pedro Ward.

The gospel was a priceless possession to these two wonderful pioneers who labored hard under trying difficulties. Sarah had twelve children of her own and the five girls that her sister Marilla left her to raise, also a grandson whose mother had died. She raised them and loved them as her own.

The striking of artesian water on this ranch was an exciting experience. Large streams of water poured from the pipes.[74] Sarah had been seen many times taking large pieces of hot bread and homemade butter out to these men while they were drilling for water. During 1898 and 1899 the Curtis family drilled fifteen wells on this ranch. Many ponds or reservoirs were made to conserve the water for the fields. Huge cottonwood and willow trees were planted around the ponds.

It was a beautiful ranch; Sarah and Dode were friends to all that called, and many travelers stopped to rest under the beautiful trees. When the house was full, they would invite the weary travelers to sleep in the barn on the clean, fresh hay. Great mulberry and black walnut trees shaded the rambling house. It had a huge kitchen, with its pungent smelling pantry and large dining table. The parlor was Sarah’s choice room, for guests could sit quietly and thumb through the red velvet picture album of her family and many relatives and friends or they had a stereoscope which you held to your eyes and passed beautiful pictures through. Sarah and Joseph both loved music, and they had a piano and a lovely tread [pump] organ which all the girls played. There were many bedrooms with the floral spreads on the beds and a large earthen pitcher with bowl on the wash stand. Last, but not least, the beautiful flowered chamber pot sat primly under the bed.

Sarah Diantha always worked right along with the girls. If it was extracting the honey she would save all the cappings from the slats of combed honey to place in another jar or tub to make vinegar from. At a certain stage this fermented honey with water made a delicious drink, it was called tizawing or mathigalong (Indian names). Some of the stands of bees were down under the plum trees where the privy stood and sometimes it became a little dangerous there while leafing through the Sears Roebuck catalog. It was a beautiful walk down there in daylight or moonlight.

Sarah Diantha’s most important work on the ranch was raising chickens and turkeys. Making butter and cheese was also important. She had ready sale for them in Tombstone, the place that was too tough to die. She had her buggy and “Old Babe” and would always take from one to four little girls along. She was so proud of these girls as she was very insistent on them keeping fair and beautiful. She would tie their bonnets on their hair and make them wear long stockings on their arms so they wouldn’t get sunburned or have coarse skin.

Sadie was a beautiful woman. She always felt presentable for company with a clean, fresh apron on, preferably a white one; this always helped to hide “my large stomach.” This very remarkable woman loved her grandchildren, and they loved their grandmother. There would always be ice cream to make and candy to pull and if they needed their shoes shined she would use the soot off the cooking stove lids to polish them up. I hear her calling: “Which one of you girls would like to bring me a pan of chips? I will stir up a nice Johnnie cake for supper. My! It will taste so good with little green onions out of the garden.” “Olive, will you go with Grandma to help push the turkeys out of the trees? If you’ll go down under the south end of the haystack and look carefully, you may find a new nest.” “Olive, will you sit under the shade of the trees and do the churning? See how quick you can make the butter ‘come.’” Olive would be tired when night came, but it was a nice bed at Grandmother’s, for she had corn shuck mattresses to sleep on.

The beautiful Lady Banksia rose bush, which was a cutting from the largest rose tree in existence, was taken from the Lady Banksia of Tombstone, Arizona.[75] This rose bush furnished a large area of shade for the Curtis family reunions for many years; it covered the entire front of the house.

Sarah Diantha Gardner Curtis. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Sarah Diantha Gardner Curtis. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.