B

Roberta Flake Clayton, Jessie Ballard Smith, Fred Shill Biggs with George and Wright Shill, and Hyrum Hendrickson, "B," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 43-96.

Margaret Henrietta Camp Brantley Baird

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Margaret Henrietta Camp

Birth: November 8, 1848; Nodaway Creek, Andrew Co., Missouri

Parents: Williams Washington Camp and Diannah Greer

Marriage 1: Thomas Burgess Brantley; July 18, 1866

Children: Thomas Richard (1867)

Marriage 2: Richard Alexander Baird; October 3, 1870

Children: James Alexander (1871), Samuel Williams (1873), Margaret May (1875), Joseph Francis (1876), Louis Graham (1878), Laura Gertrude (1880), Diannah Blanche (1882)[1]

Death: January 9, 1941; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

In all the world, it would be hard to find such a wonderful person, or one who has done, and is still doing, so much for humanity. Truly she lives “in the house by the side of the road,” and that house is in every sense a home and is a haven to storm tossed souls, who know that day and night SHE will be there to bid them welcome, and by her very example of cheerfulness help them to adjust themselves to circumstances and try to emulate her example of bravery.[2]

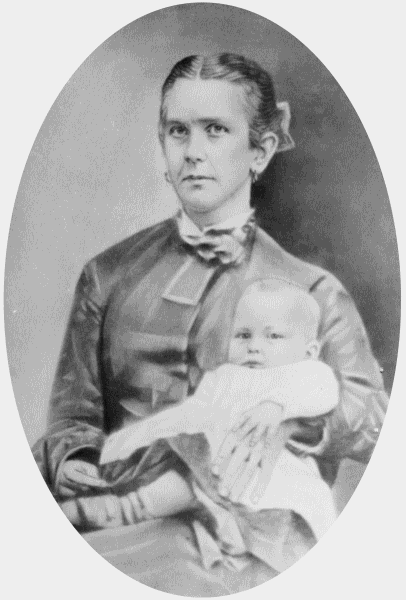

Margaret Henrietta Camp Brantley Baird with unidentified child, probably son Thomas. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Margaret Henrietta Camp Brantley Baird with unidentified child, probably son Thomas. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Margaret Baird was born on the Nodaway River, in the state of Missouri, where her family was camped en route from their Southern home to unite with the Mormon emigrants on their way to Utah. She arrived on the night of November 8, 1848, the fifteenth child in the family. It was a cold, inclement night, and for a while it was feared that neither mother nor babe would live.

From a long line of Southern aristocracy came the gentle mother of this family, who owned her own plantation and the slaves necessary to care for it, given to her as a dowry by her father at the time of her marriage. She was a devout Baptist and her husband, Williams Camp, a Campbellite minister, but when they were visited by two Mormon missionaries, Mr. Camp joined The Church of Jesus Christ and at once began making preparations to join the Saints in Illinois. Although his wife, Diannah Greer Camp, had not joined this church, her love for her husband caused her to leave her beautiful home and go with him.

The Camp family decided to remain in Missouri the remainder of the winter before continuing their westward journey. This was a swampy location, and toward spring the mosquitos were terrible. From the bites of these pests, little Margaret was afflicted with a running sore on her right leg that ate out the large leader above the knee and made her a cripple for life, necessitating always a crutch and cane to enable her to walk. Possibly because of her affliction, she never grew very large physically, but what she lacked in stature was more than made up to her in grit, and her mental qualifications were above normal.

After the family reached Salt Lake, Mr. Camp decided to take his wife and two youngest children back to their homeland to try to sell their plantation and possessions.[3] Of course the trip was made by team, as that was the only mode of travel. When they reached there they found it very difficult to sell anything, but finally Mr. Camp traded part of their property for merchandise, and teams. It took twelve wagons to convey the things to Utah. One of the most prized possessions was a beautiful piano, so large that it took one wagon to haul it. This wagon was the second in the train, and the team was driven by their most trustworthy “[mixed-race] girl. Mrs. Camp’s conveyance, a magnificent carriage with glass doors, led the procession of teams, following her husband who went ahead on his fine saddle horse, to find the best route and test the streams to see if they were safe. The other teams were driven by servants of the family, with the exception of those that were brought by three families to whom Mr. Camp furnished transportation in exchange for their services.

When Salt Lake was reached Mr. Camp established the second mercantile establishment there. In 1850 he returned again to the South and traded their remaining property for more goods. Here they remained for two years before returning to the West. Little Margaret made all of these overland trips, so she was a traveler at a very early age. On this trip the wagon train was attacked by Indians, but Mr. Camp satisfied them by giving them a beef and they were not further molested.

Because Margaret was not as strong and robust as were the other children of the family, her education was looked after possibly more than theirs; at any rate, she studied under that dean of all teachers, Dr. Karl G. Maeser.[4] She tells of one time in the spelling class: She was at the head when somehow she slipped and fell causing a disturbance. Dr. Maeser sent her to the foot of the class. After just four words were given out she was at the head of the class again. “There now,” she said triumphantly, but perhaps with a little too much emphasis. Anyway she was promptly sent to the foot again. Again she soon regained her place, but this time she said nothing. But it did not keep her from “thinking a whole lot,” she said. Because she could not walk to school, she was carried by her brother Dick, and when the snow was on the ground, she was taken on a sled.

Knowing that she was not old enough to be baptized, her father tried to put her off about it. She begged for baptism. She said she would never be able to walk unless she was. They finally broke the ice and baptized her, and her faith made her whole because she could walk for the first time in her life.[5]

When she was a small child, she showed an aptitude for music and so a teacher was employed and she was given lessons. When she was fourteen years of age, a very fine French instructor came to Salt Lake City, and she studied with him. She gave her first music lessons when she was fifteen years old and kept it up for more than fifty years.

Before she was seventeen, she was married to her first real lover, Thomas Brantley. He, too, was a Southerner, a Virginian by birth, and their happiness knew no bounds. But it was too precious to last, for he sickened and died suddenly, just a year and twenty-one days after the wedding, leaving his little wife and a six-week-old son, Thomas Junior, to mourn his loss.[6] Bravely she carried on for four years, when she married again, this time to Richard A. Baird.[7] By this man she had seven children, four boys and three girls. She continued giving music lessons and carrying more than her portion of responsibility.

For years, her husband was a night policeman in Salt Lake City and then decided to move to Sacramento, California, where work was more plentiful. He was a mason by trade. The damp climate here was very hard on her [Margaret’s] health, so he moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he could continue with his contracting and building.

While in St. Louis their seventh child was born, and here also their little boy, Louis Graham Baird, born in Sacramento, died on August 30, 1879. Neighbors had found out that the Bairds were “Mormons” and the prejudice was so strong against her people that no assistance was offered, and the poor mother had to prepare the body and the husband had to obtain the casket. Because of the unfriendliness of the people, a metal casket was procured, in which the baby was placed and hermetically sealed, and they kept the little body in the house for the remaining two years they stayed in St. Louis. At the end of that time they moved to Salina, Kansas, where a brother-in-law lived. Here the people were much kinder, and so here the baby was finally buried. The keeping of her child’s body was a great trial to her, and she says she so often dreamed of it that it was a constant sorrow.[8]

The two men worked together for more than a year in the contracting business. One night, Mr. Baird was awakened from his sleep by the growling of a dog. He got up to see what was the matter, when the dog sprang at his throat. He succeeded in knocking it off; this was repeated, and the third time the dog fastened its teeth in his shoulder and neck. This resulted in his death nine weeks later [probably due to rabies], on April 20, 1882, after the most excruciating suffering. He was a Mason, in good standing, and his Lodge looked after his widow and paid the funeral expenses.

Just ten days after her husband died, a baby girl was born to her. As soon as the baby was old enough and Margaret was able to endure the trip, the Masons chartered an emigrant car to take her household belongings and hired a nurse to accompany her and her family to Utah. Never has Margaret ceased to express her gratitude for this help in the greatest trial of her life.[9]

Margaret was too independent to remain long with her people, and so decided to go to northern Arizona where she had a sister, Catherine Ellen Camp Greer, who thought Margaret might be able to support herself and family out here by giving music lessons.[10] Therefore, she bought two yoke of big oxen and five milk cows and started for her new home, bringing all of her possessions except the treasured piano. This was left with her brother for a year, then shipped around by San Francisco thence to Holbrook, Arizona, on the train.

She left, with two other families, for a four-month trip which ended in the Little Colorado River section at the Greer Ranch, the home of her sister Ellen. This was in the month of November, 1882. She remained with her sister that winter, teaching the daughters of the family and the neighboring children. In the spring she moved into the home of her nephew, Nat Greer. She stayed here two years. While here the greatest sorrow of her life came to her. Her eldest son, Thomas Brantley, her strength and her support, was killed by a desperado [on November 20, 1883], and his lifeless body shipped home to her, from Bluewater, New Mexico, where he was working. This was almost more than she could stand. For months she seemed stunned but at last came to the realization that she must look after her remaining six children, the eldest of which was only thirteen.

In the fall she would move to St. Johns to put her children in school. The schools were better there, and there was greater opportunity to teach music.

Each summer was spent on the ranch where she and the children milked cows loaned to them by the cattlemen, who also bought cheese and butter that she made. The cowboys gave her their discarded clothing which she made over to fit her children. They made it a point to stop at her home, where they were always welcome. She never charged them for their meals or bed, but often she would find some money under their plates after they left, and whenever they killed a beef near her they always saw that she got a generous piece.

One of Margaret’s most thrilling experiences on the ranch was when the boys caught a new cow. She proved to be a terrible fighter. She bellowed and fought when they tried to rope her. Finally they caught her and tied her to the snubbing post in the center of the corral, thensnap went the rope, and the boys sought protection on the other side of the fence. Their mother deliberately made her way into the corral; the cow sniffed and came at her. She broke her cane over the cow’s head and stopped her, and she proved to be the best milk cow they had that summer.

Having been a sufferer all of her life, Margaret had great sympathy for those in distress and would endure any hardship herself to relieve others. Here is an example of her courage: A neighbor woman was about to be confined. She lived a mile and a half away, across the Little Colorado River, which at that particular time was not little as the melting snows had made a raging torrent of it, covering also the flat with its muddy waters. Margaret had her horse saddled and started on her mission of mercy, with her own baby, as there was no one on the ranch to leave the little one with. In some places the horse had to swim, but nothing daunted, the fearless rider reached the sickbed in time to save both the mother and babe.

There were no free schools when the Baird children went to school, and it cost her at the rate of $12.00 per month for their education.

After eight years of the most grueling struggle for sustenance, thru which she was not known to show the spirit of complaint of cowardice in any way, she received a legacy of $3000 from her mother’s estate. From this she bought her a farm and orchard in Concho, Arizona, and put the remainder in the Co-op Store, living from the dividend of this money, the proceeds of her farm and her music pupils.[11]

Hers was the first adobe house in Concho.[12] Her boys made the adobes. She and the two little girls hauled them from the adobe yard to the house. The children would carry them to her and she would place them in the wagon, then pile them where they were needed. She hauled every foot of lumber from the mill seventy-five miles away, thru the Apache Indian Reservation. Her helper was a boy of thirteen, and one of the little girls usually accompanied them.

On one trip the Indians were praying for rain. As is their custom they had set the timber on fire, believing that when the Great Spirit saw the smoke, He would send rain. Margaret and her children made the trip to the mill, got the lumber, and started home. When about twenty miles from the mill, they came to where a big tree had burned, causing it to fall directly across the road. It was on a rocky hillside and there was no way around it. In her cheerful way, she told the boy to stake the horses, and they would have supper. After supper she and the children unloaded the wagon, got it over the log and then by the light of the burning timber reloaded the lumber. It took into the early hours of morning to complete their task. Then they lay down to rest and sleep if they could. In the morning they had breakfast, and then came the difficulty of trying to bind the load. They tried to devise a plan to tighten up the chain to hold the load in place. The binding pole was placed under the chain, but all three were not heavy enough to pull the pole down to tighten it up, so they found a large malapai rock.[13] Little by little they got it up on the load, then they pushed it onto the binding pole and slid it toward the end, and the mother and little girl both got on with the rock, the pole came down and the load was bound, and they continued on their way.

Margaret Henrietta Camp Brantley Baird shortly before her death. Photo courtesy of the Albert J. Levine Collection, Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Margaret Henrietta Camp Brantley Baird shortly before her death. Photo courtesy of the Albert J. Levine Collection, Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

When about ten miles from their home, they met eight Indians all decked out in war paint. How frightened all three were. The Indians rode up to the wagon. Margaret could talk some Piute; this she tried on them. They forgot to be fierce, perhaps, when they saw the helplessness of this little crippled woman; anyway, they laughed at her attempt at conversation. She gave them some cookies from her “grub box” and they rode away. She motioned them that they were on the wrong road, and they went away laughing at her and swinging their arms. As soon as they were gone she said to the boy, “Now put on the whip and let’s get out of here as soon as we can.” Now was a chance to test the genuineness of their work as they went lickety-split down the mountain and the load did not loosen at all.

She always raised good gardens, crawling along on her hands and knees to weed it. On her farm she raised alfalfa, fruit, corn, and cane which was made into molasses, which she would take to the mountain country to trade for potatoes and articles of clothing.

In Concho, a very helpful spirit was felt; the women would go from house to house to spend the day and help each other with their sewing. At times they would have as many as six sewing machines going at once, while some of the ladies would cut out, baste, or finish off. Margaret was always the central figure on these occasions, as on the all-day workings during the fruit season. They would go from place to place, peeling, pickling, preserving, and drying. The children were called into service also and several hundred pounds of fruit would be taken care of a day. Margaret was considered the fastest peeler; that and her good nature and funny stories always won a welcome for her.

Because of the scarcity of pure drinking water, many cases of typhoid fever developed in the community. She was always ready to render assistance, and she never lost a case she was nursing.

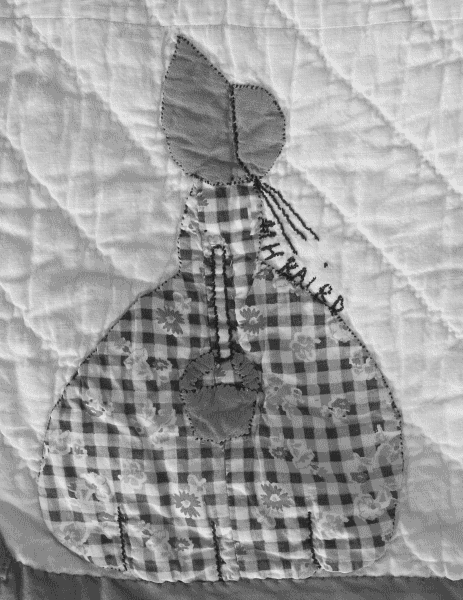

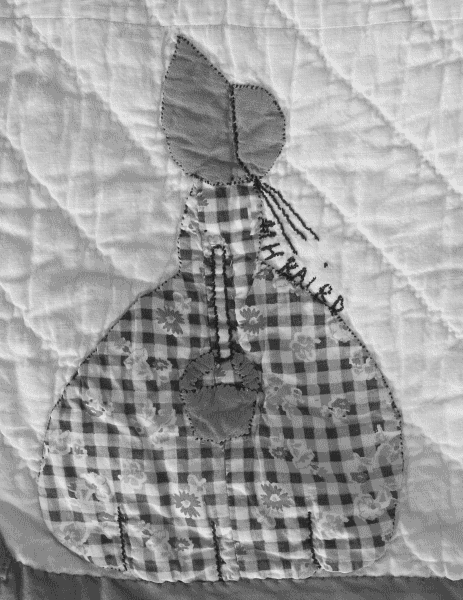

Margaret Baird's doll for the Moneta Fillerup quilt (left) and the doll her granddaughter Eloise Flake created; David H. Ellis, photographer. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Margaret Baird's doll for the Moneta Fillerup quilt (left) and the doll her granddaughter Eloise Flake created; David H. Ellis, photographer. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Whenever a boy wanted to go to school and had no money to pay board, he knew he could find a place at her home, as she was a firm advocate of education and saw that all of her own children passed the eighth grade and sent them thru high school, and the ones to college who cared to go. Her home was always open to boys and girls, whose joys and disappointments she seemed to understand.

For over thirty-five years she has lived in Snowflake, Arizona, where she also taught music, and some of the finest pianists in both Apache and Navajo Counties owe their success to the early training she gave them. Grandma Baird, as she is now lovingly called by young and old alike, is beloved by all who know her. Possessed with all of her faculties, and added to that a cheerful disposition, and an optimism that is infectious, she truly “Lives in a house by the side of the road, and is a friend to man.”

Grandma Baird died January 9, 1941 in Snowflake, Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

Margaret Baird was a beloved widow in Snowflake. The way she coped with her disabilities is illustrated in this account of a pioneer celebration held in Snowflake on July 24, 1895:

After dinner all joined in games and contests for two or more hours. A little cripple lady, who never weighed a hundred pounds in her life, took first place standing on her head. She would wind those long skirts around her legs just above her shoe tops, then close her legs jackknife fashion. In this way her skirts were held firmly in place. She would now put her hands out and in a second’s time her head was down between them and there she was upside down in mid air. She could stay thus longer than any other contestant. She also out did them all in climbing the walnut tree. After tying her skirts firmly with a heavy cord above her shoe tops, she would grasp the lower limb, draw herself up and catch a higher limb. Continuing in this way she was soon to the top of the tree, never using her legs or feet in doing so. There she sat among the top branches. After resting she lowered herself in the same fashion. She was voted the honor of being the real sport of the day.[14]

Nearly forty years later, sometime between May 1932 and November 1934, seventy-two women in Snowflake worked on a friendship quilt for Moneta Fillerup, who had been recently released as Relief Society president. These women ranged in age from twenty to eighty-four. Each of the nine-inch squares had an appliquéd doll that was a cross between a Sunbonnet Sue and a Colonial Lady. The names on the quilt were usually made to look like an extension of the ribbon from the bonnet. Each woman expressed her creativity in the flowers, basket, or purse the doll was carrying and/

Julia Johnson Smith Ballard

Jessie Ballard Smith[16]

Maiden Name: Julia Johnson Smith

Birth: October 20, 1875; Parowan, Iron Co., Utah

Parents: Jesse Nathaniel Smith[17] and Janet Mauretta Johnson[18]

Marriage: Charles Harvey Ballard;[19] November 2, 1892

Children: Jessie (1893), Annie (1896), Harvey (1897), Harold Smith (1900), Charlotte (c. 1902), Mauretta (1904), John H. (c. 1907), stillborn son (1911), Benjamin J. (1914), Frances (1916), Luella (1918), Phyllis (1921)[20]

Death: April 27, 1956; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

It was in Parowan, Utah, October 20, 1875 that a tiny baby girl came to bless the home of Jesse N. Smith and his wife Janet Mauretta Johnson, and they named her Julia. She was number seventeen in the large family of Jesse N. Smith and the fifth daughter of his wife Janet.

Julia Smith Ballard. Photo courtesy of Marta Moore.

Julia Smith Ballard. Photo courtesy of Marta Moore.

Julia was three years old when her father was called to help settle Snowflake, Arizona, and to preside over the Eastern Arizona Stake of Zion.[21] The little company composed of Jesse N. Smith, his wife Janet, her five small children and several other families left Parowan December 3, 1878.

It was not easy for Janet to leave her home and start out in the dead of winter with five little girls suffering from whooping cough, but she did not complain. It took a homemaker with a courageous heart to make a wagon box into a home during six weeks of weary travel through inclement winter weather.

This little company, consisting of eleven wagons and thirty-two people, arrived in Snowflake January 16, 1879, and were welcomed by Brothers John Hunt and William J. Flake. Little Julia was a four-year-old Arizona pioneer, but she well remembered the first night spent in the town that was to be her home the rest of her life. The Smith family was invited to stay at the home of Bishop John Hunt and his wife Lois, and Julia’s mother gave her little girls a good bath, the first they had had since leaving Parowan.

Snowflake at this time consisted of about eight small log cabins with dirt roofs besides the Stinson house. The Smith family lived in their wagon box and a tent until their two-room log house was finished. It was the first house in Apache County to have a shingled roof.

Late in the fall of 1879, after the crop was harvested, Julia’s father returned to Utah to finish his term in the Utah Legislature. His wife, Janet, and her family remained in Snowflake. In the spring of 1880, he returned to Snowflake bringing the rest of his family to settle there. Julia was so happy to see her brothers and her sisters again; they were never considered half brothers and sisters in the Smith family. Aunt Emmie’s and Aunt Augusta’s families lived in wagon boxes and in tents until their houses were finished, but they ate at Julia’s mother’s table.[22]

In Julia’s words, this little experience taught her a lesson she learned early in life:

Sunday was always a big day in our lives. It was really a special occasion when there was no work to do and we could put on our best dresses and go to Sunday School. I will never forget the lesson that I learned one Sunday morning. Priscilla, Edie and I had hurriedly changed our dresses and rushed off to Sunday School, failing to hang up the dresses we had taken off. Lucy was just leaving for Sunday School when our mother discovered the dresses on the floor and sent her in haste to tell us to come home immediately. Three little girls were very upset and frightened. Something terrible must have happened to be called home from Sunday School; perhaps our mother had had another heart spell. We ran home as fast as we could go. Mother calmly greeted us at the door, told us to hang up our clothes, then sent us back to Sunday School. We never again went to Sunday School or anywhere else without first hanging up the clothes we had taken off.

Julia grew up in a thrifty pioneer home where there was very little leisure time. In spite of this fact, she enjoyed a very happy childhood. Mother was good at reminiscing and could keep one spellbound for hours telling of the games they used to play, such as run-sheep-run, steal sticks, hide and seek, blind man’s buff, hop scotch, and old nicklebones [knucklebones?], etc.; also of joy rides on hay racks, of husking bees, and candy pulls. May Day and Fourth of July festivities were of great importance.

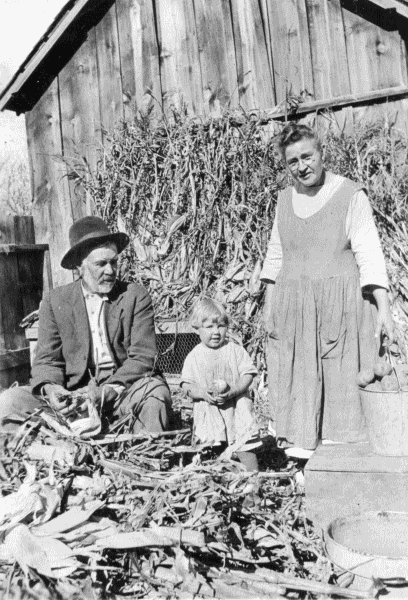

Julia Smith Ballard, with husband, Charles, and youngest daughter, Phyllis, shucking and shelling corn. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

Julia Smith Ballard, with husband, Charles, and youngest daughter, Phyllis, shucking and shelling corn. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

At a very early age Julia learned to do all the domestic tasks around the house, including sewing, knitting, weaving, and braiding straw. She loved to slip across the street and watch Grandma Larson at her loom, helping her to wind her shuttles and other simple tasks.[23] The knowledge she gained from Grandma Larson about weaving proved very beneficial in later life when she had to furnish her own home with carpets and rugs. Grandma Johnson taught her to knit.[24] When she was eight years old, she felt highly complimented one day when Aunt Emmie came to their home with some white yarn and requested Julia to knit a pair of garters for her. Grandma Janet made straw hats for both men and women. Julia helped her mother with the trade by braiding straw in several different patterns. By the time she was fourteen years old she was making all of her own clothes and helping with the family sewing. Before Leah was born, Grandma turned over the sewing to Julia, and she made all of Leah’s baby clothes.

An important occasion was required during the summer of 1892 to bring both Joseph F. Smith and George Q. Cannon, First and Second Counselors to President Wilford Woodruff, all the way from Salt Lake City to Arizona by team and wagon.[25] So much time was necessary to make the trip, due to the mode of transportation, that the Church Authorities called a district conference to include the four Arizona stakes—Maricopa, St. Joseph, St. Johns, and Snowflake. Since this conference was to be held in July, Pinetop was selected as a suitable gathering place. This conference was to serve a dual purpose. Aside from the visiting Church Authorities’ instructions and the general spiritual uplift expected, there was the added attraction of a few days camping among the pines. The latter had a special appeal to those coming from the Gila and Salt River Valleys. Wagon wheels turned over and over on the hot dusty stretches of Arizona roads as the caravans from four stakes wended their way to the White Mountains to attend the Pinetop Conference. The mode of transportation was no indication that the folks, both young and old, did not enjoy themselves.

A large lumber pavilion was built at Pinetop for this occasion. This served as a meeting place for the two days of conference on Saturday and Sunday, and for the celebration of the 4th of July on Monday. Each stake had its respective camp located around the pavilion according to its location in the state.

The quadrille was the popular dance of the day. The round dance had been discouraged by Church leaders but at the Pinetop conference 4th of July celebration several round dances were permitted because of the many requests from the young people. This was the first time the young people from the Snowflake Stake had been permitted to round dance with Church sanction.

Julia Smith attended the Pinetop Conference with her intended husband, Charles Harvey Ballard, who was full of fun and never happier than when he could play a prank on someone. It was rumored that they were to be married soon; consequently, they were subjected to a lot of teasing and fun from the young people.

Julia was very fond of pine gum. The morning they were to start home, she left camp with several others in search of a little more pine gum. As it took the men folks quite a while to tend their teams, pack their wagons, and get ready to leave, she felt that there was plenty of time to go a little farther from camp where she could select some choice pieces of gum. The farther she went the better the gum seemed to be. She became so engrossed she failed to notice that her companions had left one by one. She heard shouting, and, thinking they were perhaps getting ready to leave, started running, as she thought, towards camp. Presently she could hear wagons moving and she ran faster and faster, but no camp was in sight. When she became exhausted from running, she became frightened and began to realize that she must be lost. Although she was panic stricken, she had presence of mind enough to stop running and to try to get her bearings. She could no longer hear shouting or the moving of wagons. As she stood there scanning the country side, she saw in the distance what she thought to be a moving wagon, so she started running in that direction; if it were a wagon there surely must be a road which would help her to find her way. When she found the road, another wagon came along which directed her to camp. Although many busy years passed since that day, Julia never forgot the terrible feeling of being lost in the forest.

Julia’s first schoolteachers were Della Fish Smith and Annie Hunt Kartchner.[26] Edward M. Webb and Levi M. Savage were her instructors in the Academy.[27] She attended school until she was married and several months after. She often mentioned the yearning she felt to continue school and her mother saying to her, “You have now started in the greatest school of all, the great school of experience.” In this school she was a very apt pupil. Julia was married to Charles H. Ballard November 2, 1892, in the St. George Temple. The journey by team and wagon took two weeks both ways. As traveling companions, they enjoyed the company of Julia’s brother, John Walter Smith, and Lois Bushman, who were married the same day.[28] Although young in years [just seventeen years old], she brought skill and love for womanly tasks to her husband’s household. She cared for his five motherless children, the youngest being four years old. She was the mother of twelve children of her own, ten of whom reached maturity.

Six years after her marriage, with three children of her own added to the family, her husband was called on a mission to West Virginia. Although a small child, I can well remember how hard Mother worked to support the family while Father was away. Besides making all of the clothing except the shoes we wore, she sewed for other people, sitting up late at night and sewing by the light of a kerosene lamp. As pay for her work she received molasses, dried fruit, squash, and other vegetables.

In addition to her busy home life, she was always active in Church work, starting out as a Relief Society teacher soon after she was married. She served twenty consecutive years in the Primary, first as ward president and then as stake president. During her service in the Primary, new babies were added to the family about every two years, but few meetings were missed on that account. Not long after being released from the Primary, she was called to the responsible position of ward Relief Society president, serving in this capacity for ten years.

Her husband passed away December 17, 1923, leaving her with four small children to support and a son in the mission field. In spite of the dark days ahead, she continued on as Relief Society president for eight years after the death of her husband.

The fall after his death, calamity struck again. The family barn, containing forty tons of hay and the year’s crop of beans, squash, and vegetables, was destroyed by fire. The granary, only a short distance from the barn, contained the wheat crop and was miraculously saved although the whole side was ablaze. The only available water was a bucket brigade. Kind neighbors came to her assistance and helped to build a new barn.

As a young girl before her marriage, Julia began to help with sewing for the dead. This she continued to do throughout her busy lifetime, making the majority of the temple and burial clothes for Snowflake and many of the surrounding towns as well.[29] No matter how pressing her own work, it was never so important that it could not be set aside while she sewed for the dead, many times working far into the night when a hurried burial was necessary, never receiving any remuneration for her service. At one time one of her young daughters had been promised a new dress for a special occasion. She rushed home from school full of anticipation only to find her mother sewing on burial clothes. Her disappointment was so great she burst into tears and said, “I wish folks would quit dying so us kids could have something to wear.”

Julia Smith Ballard. Photo courtesy of Joyce Webb Brimhall.

Julia Smith Ballard. Photo courtesy of Joyce Webb Brimhall.

A few years before her death one of her granddaughters asked her if she had ever kept track of the number of people for whom she had made burial clothes. Her life had been far too busy to make a note of this service, but now that she had more leisure the idea intrigued her. In her little notebook she began to jot down the names of those she could recall sewing for. That list grew into the hundreds, and no doubt there were many that she could not recall.

Her fingers were never idle. Even in her later years, whenever she sat down she either had her knitting or a temple apron to work on. She was ever mindful of the unfortunate, always ready to share whatever she had with them.

Julia passed away April 27, 1956, in Snowflake, Arizona. The eighty-one years of her life had been filled with service to others.

Ellis and Boone:

Julia Smith Ballard’s service in making burial clothing for people in Snowflake is legendary. Upon her death, her daughter Luella Ballard Webb assumed this same role for many in the community. But burial clothing was not the only service Julia Ballard provided, as noted in this story:

While Julia S. Ballard was serving as President of the Snowflake Ward Relief Society, the custom of “Sunday Eggs” was started. The Relief Society sisters donated the eggs that their hens laid on Sunday to the Relief Society for the purpose of getting a fund to erect a new building for the sisters. Her children have covered the town over many times taking their 10 lb. buckets every Monday and going from house to house to gather the eggs. These eggs were sold (many at no more than 10¢ a dozen) and the money was literally socked away by secretary Minnie Kartchner. There were many varied and interesting experiences with these “Sunday Eggs.” There was one good sister in town whose hens never did lay eggs on Sunday while others’ hens always seemed to lay several more that day than any other in the week. One day one of [Julia’s] daughters was on her way home with a full pail of eggs, when a big dog came running out of a yard she was passing and jumped on her, frightening her terribly as well as breaking all her eggs. When the first Chapel was built (the Chapel that was destroyed by fire) a fund of $3000 was put into that building by the Relief Society, the major portion of this money came from the Sunday Eggs.[30] Can you imagine how many eggs must have been gathered to accumulate this amount?[31]

Sarah Roundy Berry

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Sarah Roundy

Birth: September 17, 1861; Centerville, Davis Co., Utah

Parents: Lorenzo Wesley Roundy and Priscilla Parish

Marriage: James Thomas Berry; October 8, 1880

Children: Herbert Alonzo (1884), Effie (1886), Zella (1888), Elmer Leroy (1891), Etta (1894), Oron Waldo (1896), Euphemia “Famie” (1898), Roundy (1903)

Death: September 21, 1941;[32] Holbrook, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Sarah Roundy was born September 17, 1861, in Centerville, Utah. She was the second daughter of Lorenzo Wesley Roundy and Priscilla Parish Roundy.[33] As a young girl, her health was very delicate and many times she fainted away. Before her marriage her mother took her to the St. George Temple to have her endowments and receive a special blessing for her health. She gradually got better and was destined to withstand many hardships during the pioneer life that was to follow.

At the age of fifteen, her father was drowned in the Colorado River while on an exploration trip in behalf of the Church.[34] This made it necessary for Sarah and her elder sister, Fannie Jane, to work some in the fields, and to do the chores as there were five younger children to care for. Her mother wove cloth for themselves and others. In the early days they knit all their stockings and knitted for others and did everything they could to help the family to get along.

Lorenzo Wesley Roundy and his good wife Priscilla had been called by Church authorities to settle Centerville, Utah, where Sarah was born and from there to settle Kanarra, Iron County, Utah, where Lorenzo was called to be a bishop of the ward, which position he held for many years.[35] Many Church authorities, relatives, and friends stopped at the home of Bishop Roundy.

James Thomas Berry was born in Spanish Fork, Utah, March 22, 1861. The Berry family was also called by Church authorities to settle Long Valley and later Kanarra, Iron County, Utah. It was at Kanarra that Sarah met James Thomas Berry. They grew up together and were baptized the same day by the same man. Tom Berry fell madly in love with the attractive daughter of Lorenzo Roundy. They were married in the St. George Temple October 8, 1880.

One year after their marriage her parents were called by President John Taylor to settle St. Johns, Arizona.[36] At this time five of the Berry families, consisting of

three brothers and two sisters and their families, made the trip to Arizona.[37] A few years later two more sisters followed to help settle the country.[38]

This Berry family drove down from Long Valley three hundred head of Durham cattle and two hundred head of horses. The parents of this large family were John Williams Berry and Jane Elizabeth Thomas Berry. John Williams Berry and a younger son, Albert Berry, helped cross these cattle over the Colorado River and then returned to their home in Kanarra, Utah.

While Sarah’s husband was busy helping to drive the cattle and horses, Sarah Berry drove two span of horses pulling two wagons on the entire trip. At times it was a frightening experience that became a nightmare as they drove down “Lee’s Backbone” into the Colorado.[39] The steep, winding road had been hacked out of the rock and was scarcely wide enough for one wagon. One of the rear wagons tipped over on a curve. Some of the men righted the wagon and, with a lump in her throat, she [Sarah] set the brakes and drove on. It was a long, tiresome trip for her. She even cut her long, thick, beautiful hair short because she did not have time to take care of it; she had a switch made out of the hair.

After three months, the Berrys turned their weary livestock loose at Concho Springs and arrived in St. Johns about the middle of January 1882. They removed the covered wagon boxes from the running gears and placed them in a circle on the ground. They served as bedrooms, and the center place was made as comfortable as possible to cook and wash and do everything there was to do. A tarp was stretched overhead for protection from the storms and sun.

Each of the families took out for themselves and eventually had homes of their own to live in. Sarah raised six children to maturity: Herbert, Zella, Elmer, Etta, Oron and Euphemia. Effie, the oldest daughter, and Roundy, the youngest son, died young. Etta was born in a house built just across the street from Bill Berry’s fine brick house. Sarah’s sisters-in-law also lived nearby, so the cousins had a lot of fun together.

Sarah was a beautiful seamstress and taught her girls to sew neatly. She loved beautiful handiwork, and her children’s clothes were adorned with it. When the children were small she knit all the stockings for the family. Like all pioneer mothers, she did her own canning of vegetables and fruit, canning and curing of meat, and made her own soap. She never owned a washing machine until her children were married.

Sarah was president of the Relief Society around the early nineteen hundreds. The Relief Society always worked hard to have a nice place in which to meet. They worked hard having bazaars to help sustain the organization and keep up the building they then owned. It was a big job to be president in those days. They made the burial clothes for all who died in the community, both young and old. They selected the best sewers in the ward and purchased material by the yard, always selecting beautiful laces and trimmings for women’s and girls’ dresses; the shoes also were made by the Relief Society. They were very particular about everything being neat as could be. After the Salado dam broke in 1905, it took all the dams below it, including the Woodruff dam.[40] The people there were in more difficult circumstances than in St. Johns, so the St. Johns Ward Relief Society donated $125 for their relief while Sarah was Relief Society President.

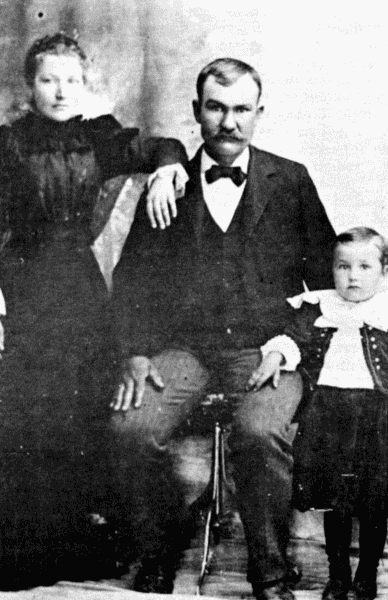

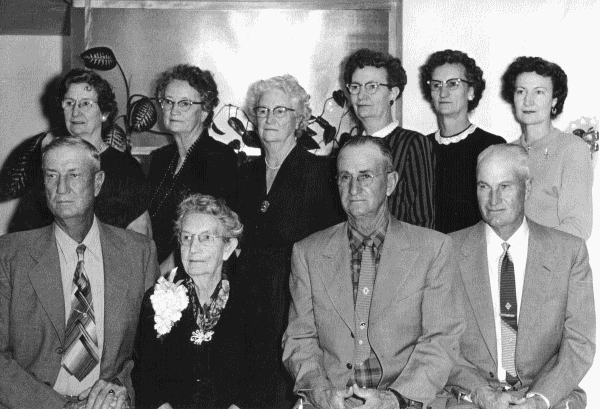

The family of Thomas and Sarah Roundy Berry: front row (left to right): Zella, J. Thomas, Sarah, Etta Berry Heap; back row (left to right): Euphamia Berry McCray, Elmer, Herbert, Oron. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

The family of Thomas and Sarah Roundy Berry: front row (left to right): Zella, J. Thomas, Sarah, Etta Berry Heap; back row (left to right): Euphamia Berry McCray, Elmer, Herbert, Oron. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

It was through her influence that the family held a Family Hour by lamplight each morning, where she read from the scriptures and they sang a song and had prayer before breakfast while the whole wheat cereal was cooking on the wood stove. Sarah was most faithful in attending to all of her church duties. She never missed a Sunday School unless there was sickness in the family. Through all the years of hardships, she was known for her stalwart character, her patience, kindness, and love for her family and her fellowmen. She was devoted to her church and served it well.

As she became older, her health became better, until at the age of fifty-eight she broke her hip. Since the same leg had been broken once before, it became shorter than the other leg, making a cripple of her the rest of her life. She didn’t walk for almost a year after this happened, but she never complained.

Sarah and John Thomas Berry spent seven winters doing work in the Arizona Temple. They hired someone to do the research for names. In all, they did over a thousand names each. They also cared for their daughter Zella, who was a partial invalid. They were very happy in their temple work and labored among the most faithful people God has on earth, temple workers.

They went back to St. Johns a little earlier that spring to get out of the heat of the valley. Just a short while after going home Sarah had a stroke from which she never recovered. Her speech was paralyzed. She lived three months this way, and passed away September 19, 1941, just two days after her eightieth birthday. She was buried in St. Johns, Arizona, in the West Side Cemetery, among the people she loved so well.

Rachel Berry (right), with daughter Lavenia Elizabeth Berry Peterson (1880-1963), granddaughter Lamore Peterson Kennedy (1909-2006), and great-granddaughter Ann Kennedy; Margaret J. Owerson, photographer. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

Rachel Berry (right), with daughter Lavenia Elizabeth Berry Peterson (1880-1963), granddaughter Lamore Peterson Kennedy (1909-2006), and great-granddaughter Ann Kennedy; Margaret J. Owerson, photographer. Photo courtesy of St. Johns Family History Library.

At her funeral, Patriarch David William Rencher, who was a neighbor for years, was a speaker, and he said: “Sister Berry was one of the most Christlike spirits it has been my privilege to know.”[41] What a compliment by a man of sterling quality!

Ellis and Boone:

The two Berry women (Rachel married to Bill and Sarah married to Thomas) were both important to the settlement of St. Johns. After the two brothers brought their cattle to Apache County, “Uncle Bill Berry became a most successful man of the range, owning both sheep and cattle.”[42] He was the first Mormon sheriff in Arizona. His wife, Rachel, became Arizona’s first woman legislator, serving from 1915 to 1917. She had worked for women’s suffrage as the Arizona Constitution was being written in 1910, but the cause went down to defeat. After February 1912, when Arizona became a state, these same women worked to bring the issue to a vote via an initiative. They were successful, and in 1914 Rachel was elected to the Arizona House of Representatives. She served one term, working in particular for the welfare of women and children.[43] She was the first woman to serve in the Arizona legislature and is the only LDS woman in the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame today.

After arriving in Arizona, Tom Berry “turned to farming,” wrote LeRoy and Mabel Wilhelm, “and found it rather difficult to thus make a living for his large family.”[44] However, he was remembered as kind, honest, and faithful in church attendance. Likewise, his wife, Sarah, known familiarly as Sady, was described as humble, gentle, and a devoted wife and church worker. While they were serving in the Arizona Temple, their oldest son, Herbert, was in Snowflake serving as a home missionary with Martin D. Bushman, Virgil Flake, Jesse Decker, Eugene Flake, and Ammon Morris.[45]

Ella Deseret Shill Biggs

As told to Fred Shill Biggs and written by George and Wright Shill[46]

Maiden Name: Ella Deseret Shill

Birth: November 16, 1869; Croydon, Morgan Co., Utah

Parents: Charles Golding Shill and Harriet Stronach Paynter[47]

Marriage: Thomas Piercy Biggs; January 19, 1888

Children: Thomas Charles (1888), Jonathan George (1890), Wilford (1892), Frank Piercy (1894), Henry (1897), Fred Shill (1898), Ellis Darrell (1902)

Death: October 10, 1927; Lehi, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Ella Shill Biggs was born November 16, 1869, at Croydon, Morgan County, Utah. She is the first child and only daughter of Charles and Harriet Shill.

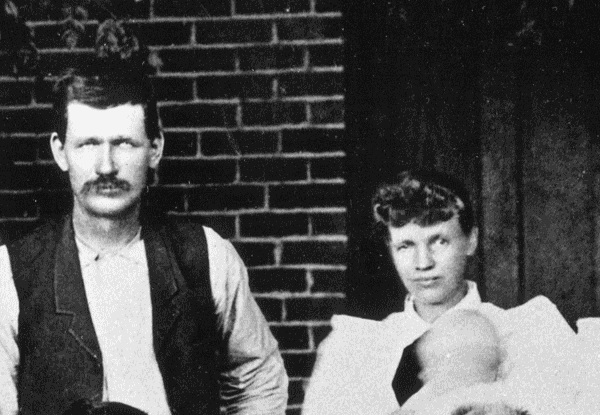

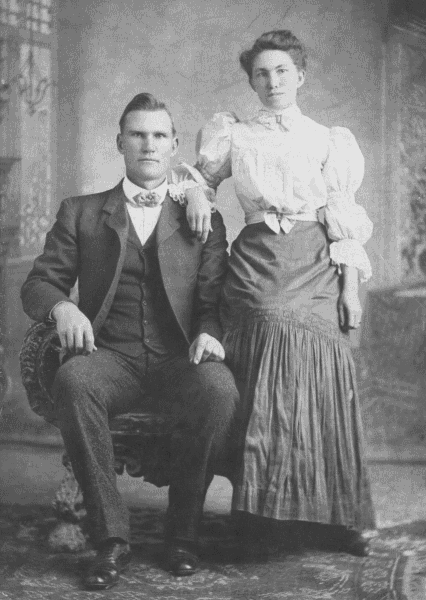

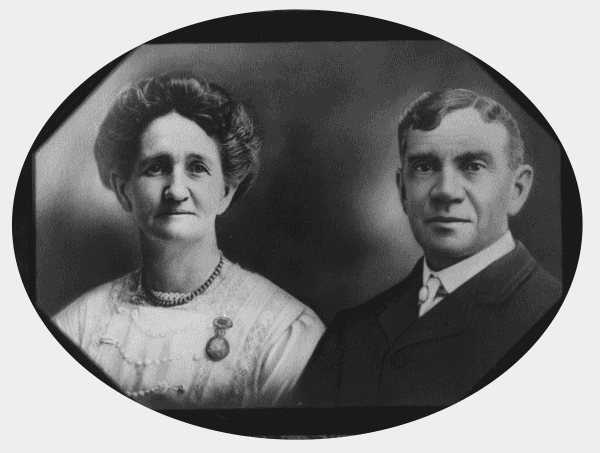

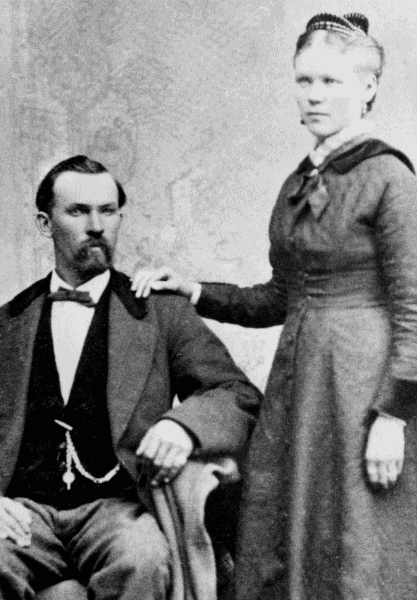

Ella Deseret Shill and Thomas Piercy Biggs with baby Henry, 1897. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Ella Deseret Shill and Thomas Piercy Biggs with baby Henry, 1897. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Ella grew to young girlhood at Croydon helping her mother tend five younger brothers and assisting her mother in every way possible. Her mother had several severe sick spells.

Early in November of 1880, after her mother had recovered from a long case of typhoid fever, the Shills loaded all their earthly belongings on the train and headed for Arizona. The trip was long and hard. There were few free moments for Ella, as there was an eight-month-old baby to tend and assist with meals for the family. After several days and many changes of cars they arrived in the town of Maricopa, a terminal point for Tempe and the rapidly growing Salt River Valley.[48]

While in Maricopa, they met a young freighter from the Lehi community by the name of Thomas Piercy Biggs. They made arrangements with him to haul the family and their belongings to Lehi. This was an exciting journey for the young boys riding atop the freight wagon.

When arriving in Lehi, the Shills settled on the land where the Otto S. Shill family is now located on North Mesa Drive. A vineyard and fruit trees were planted. Then Father Shill got a job as foreman on the George Crismon Ranch. The ranch is now known as the Sachs Ranch, located about midway between Lehi and Tempe on Alma School Road. Mr. Crismon came to the valley to raise pigs and make bacon and ham for the valley and the soldiers at Fort McDowell. The Shills lived on this ranch for two or three years.

Schooling for Ella was very meager. She reached the fifth grade when she was forced to quit school to help care for the family. As a young lady she moved to Pinal, Arizona, to work for Ben and Rebecca Blackburn.[49] She worked for them as long as the Silver King mine was in operation.

After moving back to Lehi she fell in love and married Thomas P. Biggs in the Logan Temple in 1888. To this marriage seven sons were born, two of them dying in infancy.

In April of 1902 a great sorrow came to this young family when death took the husband and father. It was a hard struggle for this young mother, as her youngest son was born late in June of 1902. Hard work and bad luck was no deterrent to her. Many times there was hardly enough food in the home for her family, but through her knowledge of the weeds that grew along the ditches and fence rows, she gathered greens for this family.

Ella Deseret Shill Biggs. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Ella Deseret Shill Biggs. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Ella had a growing testimony of the gospel—even in her darkest hour she never doubted or complained. She instilled this testimony and the love of the gospel in her sons and to always respect those in authority. Two of her sons, though hard times were pressing, filled honorable missions.

Ella was a faithful worker in the Sunday School and the MIA. For several years she was the president of the YWMIA. She also acted as secretary of the Relief Society under three or four presidents.

Among other activities she carried on was keeping the Lehi store, [working as] postmistress of the Lehi Post Office, and sewing for the Indians, for whom she had a great love. Also, if there was any sick in the community, Sister Biggs was the first one called.

After living a very full life she passed away in her home October 10, 1927, leaving a large and respected posterity.[50]

Ellis and Boone:

It is well known that Ella’s brothers, Milo and Frank, along with Frank Biggs and Lawrence Ellsworth went prospecting, although they did not find the gold they sought.[51] Many of the Mormon men in southern Arizona worked for the mines, usually hauling ore, sometimes hauling produce, and occasionally in the mine itself. Less well known are the women that worked at the mines.[52]

In 1875, four local farmers located an ore body on the Stoneman Grade between Florence and Globe, near Picket Post Butte. They filed notice and called this the Silver King Mine. For the first shipment, they carefully packed poor grade ore and discarded the good. They lost $12,000 and could not sell their site to pay a small debt. Two years later, some real miners from Nevada noticed the rich ore in the dump and contracted to split the profits. This shipment netted a profit of $50,000. Immediately, the Silver King Mine became an important source of silver from Arizona, and within nine years it had produced more than $6,000,000.[53]

At this same time, the town of Pinal, also called Picket Post or Pinal City, was established to support the hundreds of prospectors and miners who flocked to the area hoping to become rich. Stamp mills were erected and ores were smelted. All these men needed board and room. Ella’s cousins, Ben and Rebecca Blackburn, probably ran a boarding house with Ella helping to provide the meals. As with most mining operations, this was a boom-and-bust location; the Silver King Mine had closed by 1888, and the town soon vanished. This area today is the site of the Boyce Thompson Arboretum.[54]

Frieda Zeigler Bourn

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview

Maiden Name: Frieda Zeigler

Birth: April 10, 1862; Markgrolningen, Stuttgart, Germany

Parents: John Siezel (Ziglear) and Friericka R. Kaufman

Marriage: James W. Bourn; c. 1885 (div?)

Children: Ralph E. (1886)

Death: October 31, 1946; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Greenwood Crematory, Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Some people spend so much of their lives trying to find their niche that there was no time left for accomplishment, but not so with Frieda Ziegler Bourn, whose first thought is of service to others.

In the year 1881 after a slow, tortuous trip of several weeks, because of delays owing to floods and lack of transportation facilities, Mrs. Bourn came to Denver from New York. Nothing ever escaped her notice and her inquiring mind went back to the cause of floods and their control instead of complaining at conditions as most of her fellow travelers were. Her interest in flood control led to their prevention through reforestation. Because of her work along these lines and her efforts to have forestry taught in the schools of the state, she became acquainted with and a good friend of Gifford Pinchot, appointed by President “Teddy” Roosevelt to look after lands under public domain.[55]

Fitted by nature as a teacher and being able to speak three foreign languages (German, French, and Swedish) her services were much sought after in settlement work. She was instrumental in organizing and conducting free kindergartens in localities where the people were too poor to afford to pay. Her knowledge of German helped her to assist many German Jews in Denver to adjust themselves to new surroundings and to each other.

Mrs. Bourn’s husband was an invalid for many years before his death, which placed upon her the necessity of providing for herself and her one child, Ralph, made permanently deaf by a severe illness.[56]

They acquired a ranch in Colorado and went into the cattle business.[57] Mrs. Bourn had to drive several miles to the post office in the winter time through banks of snow. Then, she saw again the necessity for planting trees when she would pass half a dozen, or more, carcasses of cattle which had died through lack of shelter and protection that trees might have offered.

During a trip to Washington en route to Philadelphia to put her son in school there, she appeared before the committee on Land Affairs to obtain title to her land, and while there was instrumental in helping to pass laws beneficial to the stockmen of Colorado.

Her interest and intelligent research in forestry, soil erosion and conservation, and the articles written by her, brought much favorable comment and may we say in a way, was responsible for these subjects being taught in the schools in Colorado. In some of the states, it resulted in large, burned-out areas being replanted with seed imported into this country from Europe, principally the Norway pine.[58]

Through her indefatigable efforts along all these and many other lines, Mrs. Bourn’s health failed, and she sought the salubrious climate of Arizona, where she found not only health but a vast field of pioneering along the lines in which she had been so successful in her former home.[59]

Having an “underprivileged” child of her own, and knowing the handicap placed upon those unfortunates, Mrs. Bourn immediately set about finding a remedy, and her home in Gilbert was turned into a training school for this group.

Soon she outgrew the small town of Gilbert. She taught in a vocational school held in the basement of the Monroe School in Phoenix. Not only did she teach sewing, cooking, care of children, and health subjects to the hundreds of women and girls who came to her school, but she interspersed citizenship and kindred subjects to the men who gathered in at the noon hour and after school closed at night. She taught them how to sign checks, conduct their business, to speak and write English, and show loyalty to their adopted country.

Instead of a nine till four o’clock school, hers extended to nine at night. She was never too tired to give ear to their troubles and unlike many who merely “sympathize,” Mrs. Bourn went to work doing something about it, and she had enough influence among those who had the power to establish centers where her work could be carried on. For years at a time, she has kept one or more afflicted children in her home.

Though advancing years have whitened her hair and left their imprint on her face, her soul is enriched by her experiences, and her desire and determination to carry on for the alleviation of suffering and to find place for the misfits of society is uppermost in her mind.

She had a small acreage near one of the rural schools where she hopes, in some way, to have cottages where these unfortunates can be scientifically fed and trained to fill their places in the world’s activities, instead of the insane asylums, delinquent homes, and jails as they do now.

Her efforts are untiring to interest the legislature in setting aside an appropriation for this purpose, and she says, with a twinkle in her kindly blue eyes, “If they will, I’ll never ask for a pension.”

For the good of all, may her hopes be realized and thus will honor and joy come to Arizona’s foremost vocational teacher and pioneer along these lines.

Frieda Bourn died October 31, 1946. She was eighty-four years old.

Ellis and Boone:

Some of Frieda Bourn’s moves can be traced in the U.S. census records, but not all. In 1900, Frieda was living with her husband, James W. Bourn, and son, Ralph, age thirteen, in Delta County, Colorado.[60] James W. Bourn was born January 30, 1852, in Missouri, and their son, Ralph, was born July 31, 1886, in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

By 1910, Frieda had left her husband and was living with a friend in Denver.[61] She was one of the women who came to Arizona as a health seeker. As Frances E. Quebbeman wrote, “The population of Arizona more than doubled in the decade of the 1880s and a considerable portion of this increase could be ascribed to the vigorous advertising of the territory as a health resort.”[62] The dry air of Arizona was considered desirable for kidney disease, rheumatism, and most importantly, tuberculosis, which was epidemic throughout the United States. After the turn of the century, pneumonia became the leading cause of death for lung disease rather than tuberculosis, and post-pneumonia patients also came to recuperate, a process that often lasted years.

Eventually, all three members of the Bourn family relocated to Arizona. By 1930, Frieda was living at Osborn, and her son, Ralph, with a wife and three children, was living in Creighton. Both are towns in Maricopa County. Then by 1940, James W. Bourn, age eighty-eight, was also living in Phoenix. All three were living in separate households.[63] It should be noted that Frieda’s son, Ralph, was deaf, and although there may have been other disabilities that are not reported in the census records, today this would not be a reason for placing a person in an “insane asylum, delinquent home, or jail” as implied in Frieda’s work to train the disabled.

Margaret Ellen Cheney Brewer

Hyrum Hendrickson[64]

Maiden Name: Margaret Ellen Cheney

Birth: October 28, 1876; Fairview, Sanpete Co., Utah

Parents: Elam Cheney and Harriet Edgehill

Marriage: Joseph Lewis Brewer; October 16, 1892

Children: Wilford Woodruff (1895), Violet (1909)

Death: September 22, 1968; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Show Low, Navajo Co., Arizona

Everyone loves a happy personality. Take equal parts of cheerfulness, thoughtfulness, order, and tact, and season well with contentment and self-forgetfulness. Then mix thoroughly all these ingredients with the milk of human kindness, and add enough common sense to hold all together, and serve on crisp leaves of sense of humor. This recipe for happiness has been tested the world over and has never been found wanting. Anyone fortunate enough to share a few minutes with Mrs. Margaret Brewer comes away convinced that here is a person that cooks daily from the recipe for happiness.

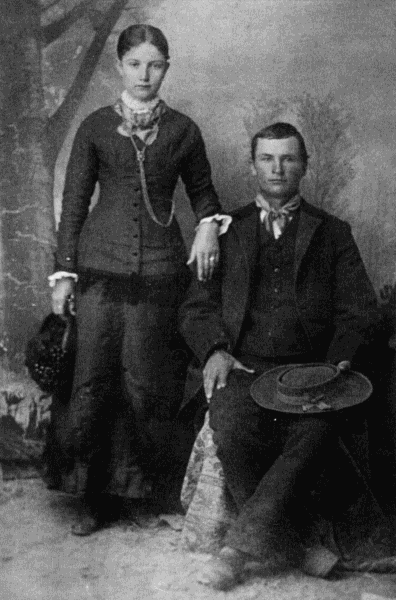

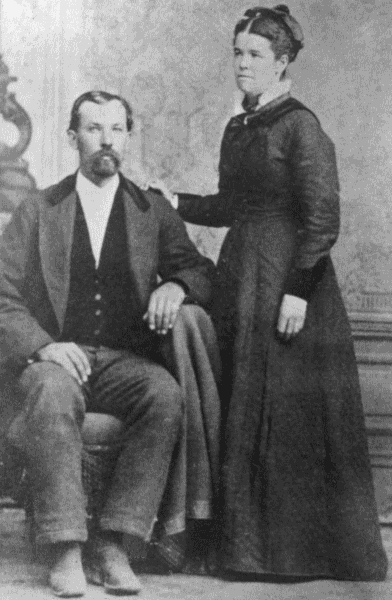

Margaret Cheney Brew with husband Joseph Lewis Brewer and son Wilford, c. 1896. Descendants of Lewis Brewer, 35.

Margaret Cheney Brew with husband Joseph Lewis Brewer and son Wilford, c. 1896. Descendants of Lewis Brewer, 35.

She has a vivid memory of an incident that occurred seventy-seven years ago, in the community of Fairview, Utah. Though only four years old, she and her cousin were asked to sing a duet at a church conference. As they stood on a table where they could be seen, they harmonized very well. After the performance, little Miss Margaret remembers Eliza R. Snow, noted LDS Church worker, standing up and talking to the people assembled.[65] She was telling the congregation about Joseph Smith, organizer of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She held up a watch and chain and said, “This is the watch and chain worn by the prophet.” The words and scene made an impression on young Margaret Cheney, that has lasted on down through the years.

Our personality’s grandfather was Aaron Cheney, who was born in New York. Her father was Elam Cheney, born May 16, 1825, at Freedom, New York. The Cheney family was moving to Kirtland, Ohio, [when] sickness interfered with their trip, and they stopped at a place called Decatur, Ohio, to recuperate. While they were convalescing there, a young man named Joseph Smith stopped in their community on his way to Washington, to seek an audience with officials. The young man spoke of his religious convictions, and young Elam Cheney was so impressed that he later affiliated with the LDS Church. Mr. Cheney later followed the migrations of the Church from Kirtland, Ohio, to Missouri, then to Nauvoo. Prior to leaving Nauvoo, he married his first wife, Hannah Kempton, in the temple there. When the Saints were driven west from Illinois, he traveled with the company that arrived in the great Salt Lake Valley, October 5, 1847.

The same day he arrived in the barren valley of Utah, his wife to be, namely, Harriet Edgehill, was born in England. Little did the twenty-two-year-old Elam Cheney realize that sixteen years later, he would marry this young girl from England. Because of bitter persecution, the Edgehill family was baptized at night. The missionary performing the ordinance had to cut a hole in the ice. They left England in 1863 and, with team and wagon, crossed the Great Plains into Utah. Mr. Edgehill was a mason, and moved with his family to Nephi where he could work at his trade. It was here that Harriet Edgehill and Elam Cheney met and were married. Fifteen children blessed this marriage; however, the grim reaper took a heavy toll, and only six of the fifteen grew to maturity.

The fifth child was Margaret Ellen Cheney, our personality. She was born in Fairview, Sanpete County, Utah, October 28, 1876. Her father was a polygamist. Margaret’s mother was the fifth wife of Elam Cheney. Mr. Cheney operated a grist mill at Fairview. He had three homes in this community, for three of his wives, another home in Springville for another wife, and a fifth residence in Idaho, for the fifth wife. Mr. Cheney carved his mill stones out of native granite rock for his gristmill. When federal authorities began taking polygamists in to stand trial, many of the men went into hiding. Elam Cheney sent his wife, Harriet, and his first wife to Payson, Utah, to live. Miss Margaret was only five at the time. The family stayed in Payson for two years when a decision was made for Elam Cheney and the two wives at Payson to leave for Old Mexico to avoid persecution. They traveled by rail to Yuma, Arizona. Mr. Cheney was in poor health and decided to interrupt his move to Mexico and visit his two daughters living in the Tonto Basin.[66] While visiting with his relations his health began to improve rapidly, and he decided to remain in Arizona. The family settled in Pinedale in 1884. They purchased a three-room log house where the Elijah Thomas brick house now stands.

As a young girl, Margaret was told so many hair-raising stories about the dangerous Indians that, when friends told her a red sunset meant the Indians were coming to massacre them, she readily believed them. Her school days were all spent in Pinedale. Joseph W. Smith was her first teacher, then Willard Mortensen, Della Fish Smith, Homer Bushman, and William Reed.[67] The favorite game played was baseball, and Miss Margaret held her own with boys or girls, playing first base.

Three Brewer brothers had settled in Pinedale: Jacob, Charles, and Joseph. Jacob had a son, Joseph Lewis Brewer, who cast a romantic eye at Margaret Cheney. After a courtship of approximately two years, they were married in Pinedale by Bishop Peterson, and early next morning, this couple, in company with Adam Brewer and Jesse Kay and Jesse Kay’s wife, left by team and wagon for the St. George Temple.[68] It took three weeks to make the trip because the Jesse Kay team kept wandering back toward home each night they camped out.[69]

When Joseph Brewer and his wife, Margaret, returned to Pinedale, they began farming and sawmilling. March 11, 1895, their first child, Wilford Woodruff Brewer, was born. A cataract began developing in Mr. Brewer’s eyes that impaired his vision. By 1899 he had completely lost his sight.[70] The wonderful person Margaret is was demonstrated at this time. She had the eyes, and her husband had the strength. They began hauling freight from Holbrook to Fort Apache. She would lead her husband about, telling and showing him what had to be moved and loaded, then the two of them with their four-year-old son would make the long trip by wagon from Holbrook to Whiteriver with Mrs. Brewer driving.[71] On one occasion when they had camped for the night, their young son, Wilford, led his father out where the horses were grazing, and Mr. Brewer hobbled the front feet of the first horse. The boy’s attention was distracted, and he didn’t notice that his father by mistake put another hobble on the hind legs of a young fractious horse. Mrs. Brewer has always felt that an over-ruling providence protected her husband from a serious injury or possible death. Another time, they camped between Indian Pine and Whiteriver for the night. During the night, a band of drunk Indians stopped nearby, and a big pow wow was held. The Brewers worried all night, fearing they would be discovered, but the night passed peacefully.[72] As soon as they accumulated enough money to send Joseph Brewer to the hospital, Margaret put him on the train at Holbrook and he traveled to Denver where he had an eye operation. It was two months before he could return home and a year before his sight returned. This was a very difficult time for the family, and they were taxed to the limit to keep going, but they never asked for any outside help.

Their second child, Violet Brewer, was born October 13, 1909. The family moved to Show Low in 1913 where they lived since. When World War I involved the United States, Wilford Woodruff Brewer, their only son, was drafted in, and by June of 1918 was fighting in the front trenches in the Argonne Forest. Just a few days before the November 11th armistice, the shrapnel from an explosion shattered his knees and the mustard gas burned his lungs and feet. His company lost him, and in January 1919 sent a cablegram to the family, that their son was lost in action. In the meantime, someone had picked him up and taken him to a hospital. As soon as he was able, he wrote his parents about his condition and where he was. It was several months before he was able to return to the states. He was never able to work much, and on January 12, 1921, he passed away from damaging effects of his war injury. Three years later tragedy struck again, leaving them with no children. Their daughter, Violet, was attending the Snowflake Academy when she contracted typhoid fever, and after a five-month illness, passed away, February 20, 1924.

When Mr. and Mrs. Brewer moved to Show Low, they were awarded a contract to haul the mail from Show Low to Standard and Clay Springs. Viola Hunt Whipple recalls what a cheerful and welcome sight it was to see Joseph and Margaret Brewer coming with the mail, riding on their small wagon. Said Mrs. Whipple, “They always enjoyed one another, and had such a keen sense of humor.” They were always able to entertain themselves. Following the mail contract, Mr. Brewer made shingles by hand. He had a one-hand knife for cutting the shingle and another knife about fourteen inches long to shave one end of the shingle. He was an expert with the knife. The old Ellsworth home in Show Low was originally covered with Mr. Brewer’s shingles, and several of the old homes in Snowflake and Taylor were roofed over with his handmade bunches of shingles. Along with his shingle making, he also farmed forty acres south of Show Low and irrigated a small plot of ground across the creek.

Mrs. Brewer has lived on the same acre of land since moving to Show Low in 1913. They built a lovely home on the corner, and the maintenance and beautification of this home and the grounds surrounding it has been the pride and joy of Mrs. Brewer. The shade trees in her yard are majestic in arrangement and structure. Her smooth green lawn is the pride of the community of Show Low. The flowers and shrubs are so arranged to add a feeling of peace and harmony as you enter through her front gate. Her home both inside and out is painted with blending colors that please the eye. An Army inspector with his white gloves would have a hard time finding a speck of dust in her comfortable home: cheery rugs on shiny floors, sturdy and comfortable chairs and sofa, pictures of loved ones on the piano, beautifully designed coverings on tables and chair arms, a variety of potted plants at the south window, the pleasant aroma of homemade chili sauce, and the appetizing odor of freshly picked apples from her own orchard. Truly it is “Home, Sweet Sweet Home.”[73]

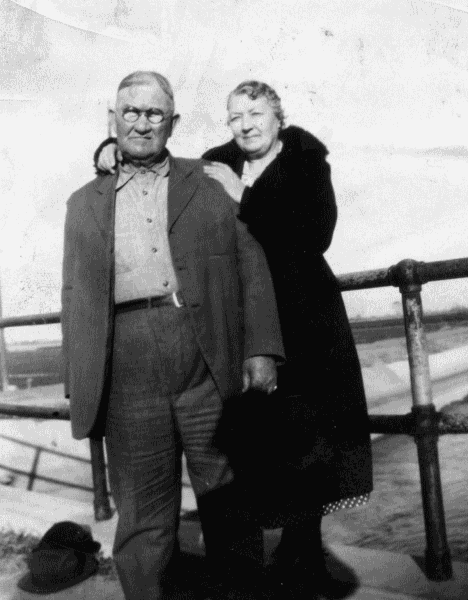

Joseph and Margaret Cheney Brewer on a bridge crossing a Mesa canal. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

Joseph and Margaret Cheney Brewer on a bridge crossing a Mesa canal. Photo courtesy of Lucille Brewer Kempton.

During 1938, Mr. Brewer’s health began to fail: first rheumatism, then arthritis. By 1941, he was confined to a wheelchair. Though he was a large man, his wife took good care of him, helping to move him around and in and out of the wheelchair. She showered on him all the love and affection and care a devoted wife could give. He passed away January 12, 1942.

Many people enjoy the blessing of a numerous posterity to help share their sorrows. Margaret has not been as fortunate. Today her brother, Hyrum, living in Florida, is the only member of her own family left. A granddaughter, by her son’s marriage, a short time before he died, represents the family posterity.[74] Yet, she has never felt to complain or seek sympathy from anyone. Through the years, she has been a faithful church worker. She served as a Primary president in Show Low for thirteen years and has been a teacher in one or more of the Sunday School, MIA, and Relief Society organizations continuously for over six decades. Since moving to Show Low in 1913, she has bound almost every quilt the Relief Society has made. A few years back, the Relief Society organization made ninety-six quilts in one summer session. Margaret bound most of them. She has quietly gone about doing good for so many neighbors and friends. Idleness has no place in her life. If she listens to the radio, she keeps her hands busy with the crochet hook or embroider needle. Her great desire is to be able to keep up her home and her beautiful yard. Said Mrs. Brewer, “I hope I will never have to be waited on—but can keep going to the end.”

She has found time to travel extensively. When she takes a trip down to Florida to see her brother, Hyrum, she makes a circuit of many states while traveling. In fact she has been in every state in the Union. Her love for children is unexcelled. She loves to teach them and enjoys having them come to visit with her. Never a person to pray in public to be heard of men, rather she has chosen to do her charities and kindnesses in secret, and the Lord has blessed her with a recipe for happiness that modern psychologists could do well to follow. Said one of her neighbors, “She is growing old so graciously.” What a nice compliment!

Today, as you approach your eighty-first birthday, we join in wishing you a most pleasant anniversary. We hope you have the kind of day that really is a happy one, in every single way. In the year ahead may you continue to partake of the recipe for happiness. It is a real pleasure to feature you as our personality of the week.

Ellis and Boone:

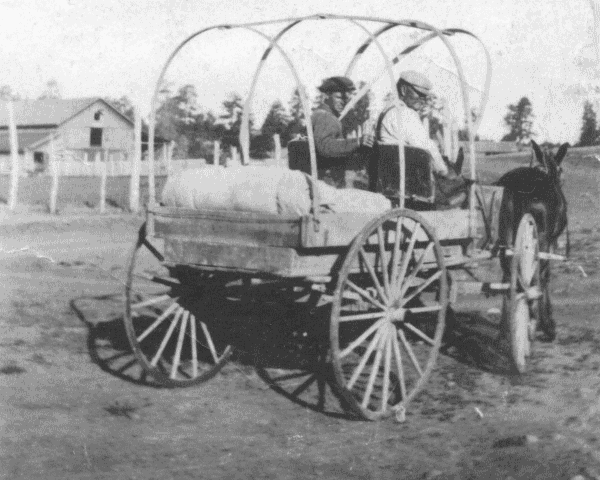

Although Margaret Brewer usually accompanied her husband as he traveled with the mail, here William Henry Lewis (left) is catching a ride with Joseph Brewer as he takes the mail from Show Low to Pinedale. Photo courtesy of Sheila McCleve Stewart.

Although Margaret Brewer usually accompanied her husband as he traveled with the mail, here William Henry Lewis (left) is catching a ride with Joseph Brewer as he takes the mail from Show Low to Pinedale. Photo courtesy of Sheila McCleve Stewart.

In 1936, RFC was submitting field reports (i.e., rough drafts) to the FWP for towns in Navajo County. E. J. Webster was then given the assignment to rewrite many of these. They wrote that Pinedale received its name from the location, “a small dale or valley among the pines,” although the name had earlier been Mortensen (after the original settlers) and Percheron for the fine horses raised there. Pinedale was twenty miles southwest of Snowflake. They included the following history, which helps understand Joseph and Margaret Brewer’s early married life farming and sawmilling in this area:

Neils Mortensen, his sons James and Willard, and son-in-law Neils Peterson, Mrs. Sop[h]ia Johnson and sons Louis an[d] Ant[h]on were the first settlers arriving in Jan. 1879.[75] Their farms were a little to the east of the present location. In 1880 a small saw mill was built at what is now the Pinedale Ranger Station, by Tom Willis, Tom Jessup and Simon Murphy. In 1882 William J. Flake brought in the large saw mill that he had purchased from the Mormon Church and [was] known as the original Mt. Trumbull mill. This location was called Snowflake Camp. For several years this mill was in operation, furnishing employment for the men and lumber and shingles for their houses. Portions of this old mill serve as a landmark to Pinedale and are much prized by them as such.

In 1882 the townsite was roughly surveyed by James Huff and Jacob and Charles Brewer. The first school was taught during the winter of 1883–84 with John Wilson as teacher. His salary was paid in produce. The following summer a schoolhouse was built in time for school that fall. All of the settlers had come from Utah and had brought with them cattle, horses or sheep. Because of its mountainous location in the tall timbers[,] it furnished an ideal rendezvous for desperados [and] horse and cattle thieves, and the settlers suffered much loss and humiliation at the hands of some of these outlaws.[76]

RFC and Webster described Pinedale as a small town supported by the industries of stock-raising, dry-farming, and lumbering. Then in 1922, another sawmill was built two miles south of Pinedale; it was owned by the Standard or Cady Lumber Company, and by 1936 James McNary had purchased it.[77] But before the town of Standard was established, Joseph and Margaret Brewer had moved to Show Low. There they continued to find support from the forest industries with Joseph Brewer making and selling wood shingles.

Margaret Brewer lived another eleven years after Hendrickson wrote this sketch. She died September 22, 1968, in Mesa but was buried in Show Low.

Sabra Ann Follett Brewer

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Sabra Ann Follett

Birth: September 15, 1847; Painted Post, Steuben Co., New York

Parents: Joseph Follett and Cynthia Stiles

Marriage: Jacob Brewer; May 24, 1864

Children: Jacob Albert (1865), Joseph Lewis (1867), Charles Frederick (1869), Harriett Louisa (1872), Adam Rufus (1874), George Franklin (1876), John Hyrum (1878), Emma Ann (1880), William Henry (1882), Cynthia Jane (1883), Alice May (1886)

Death: September 18, 1908; Safford, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Safford, Graham Co., Arizona

“But Ann is too young,” answered her mother to the young couple. “She is only sixteen and not of an age to know her own mind.”—Sad words to the ears of Jacob Brewer and his young sweetheart, Sabra Ann Follett.

Sabra Ann Follett Brewer. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Sabra Ann Follett Brewer. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Since their introduction by her cousin, Adam Campbell, their shy friendship had grown into a warm love for each other.[78] They had found that their lives held a great deal in common. Both had been born in New York State (Jacob in Sullivan County on June 21, 1833, and Sabra Ann in Steuben County on September 15, 1847). Both came from families who had been converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by early missionaries. Both families had joined the Saints in crossing the plains to Utah.[79] Both young people loved the Lord and his restored gospel.

Their young dreams were not to be easily thwarted, however. If they could not win Ann’s mother’s approval now, perhaps they could better win it as man and wife. So they planned for a secret marriage and eloped on May 24, 1864.

This was the beginning of a long and very happy life together. Although they were called upon to bear many sorrows and trials to test their great love, they met life triumphantly. Through the years Jacob and Ann were not to be blessed with many of the material things, but they were ever blessed with rich spiritual blessings. They rejoiced in the great blessing of parenthood and took great joy and satisfaction in the knowledge that all of the members of their family were cooperative, clean, and virtuous. Because they loved the Lord, they were willing to make the many sacrifices necessary to serve Him.