A

Barbara Ann Phelps Allen, "A," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 33-42.

Barbara Ann Phelps Allen

Autobiography

Maiden Name: Barbara Ann Phelps

Birth: August 26, 1877; Montpelier, Bear Lake Co., Idaho

Parents: Hyrum Smith Phelps[1] and Mary Elizabeth Bingham[2]

Marriage: John Seymour Allen;[3] October 2, 1895

Children: Charles Ashael (1896), Blanche (1898), Hyrum Loren (1901), Barbara (1903), John R. (1905), Gove Liahona (1907), Mary (1910), Eldred Phelps (1912), Russell Hoopes (1914), Ben Rich (1916), Joseph Seymour (1917), Della (1920)[4]

Death: January 31, 1957; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

My parents were Hyrum Smith Phelps and Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. I was born August 26, 1877, at Montpelier, Bear Lake County, Idaho. I was sixteen months old when my family moved to Mesa. The first house that Father built was on the corner of Second Ave. and Hibbert.

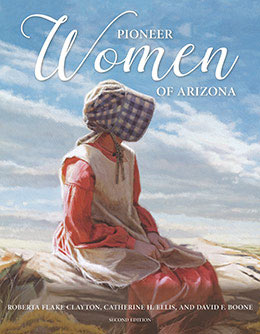

This is the photograph that Barbara Phelps Allen included for herself in her book, Ancestors of the Children of Hyrum Smith Phelps. Photo courtesy of Mesa Family History Library.

This is the photograph that Barbara Phelps Allen included for herself in her book, Ancestors of the Children of Hyrum Smith Phelps. Photo courtesy of Mesa Family History Library.

Among my first recollections of this place, Mesa, was the first Sunday School I attended. It was held in the schoolhouse, a one-room adobe. Hannah Peterson (Miller) was the teacher. We recited the alphabet from cards. We were seated on a low bench in the front of the room. I attended my first Primary with my sister Lucy.[5] We were very devoted to each other. Each week we anxiously waited while the secretary read the program for the following week, but we never got put on the program. I never went anywhere without Lucy.

When I was nine years old, the school put on a program and every child in the room was given a part but me. I felt disgraced and I never even told my mother. I always remembered the feeling I had, and in the sixteen years I presided over the Primary, I always favored the backward child and never slighted anyone to my knowledge.

Father built a long room on the back of the house to accommodate the growing family. Grandmother Bingham lived with us a while before moving to a house where the Sixth Ward now stands (on the corner of Mesa Drive and University). We children were staying with her after Father was taken to the Yuma penitentiary.[6]

When I was twelve years old, Mother gave me an accordion for Christmas. I soon learned to play it. A few years later, she and Lucy gave me a larger one, which I kept until after I was married.

One time Father went to Tempe and bought a bolt of cloth called zephyr gingham; it was a beautiful plaid. As I remember, five of us girls had a dress alike. Lucy and I always dressed alike. Most people thought we were twins.

The first MIA class I attended had only one class for everyone. Pres. Charles I. Robson told the story of Joseph Smith’s first prayer.[7] That was the first time I had heard it and I have never forgotten how it impressed me. Soon after this, Lucy and I were asked to sing at one of the meetings. We sang “Write Me a Letter from Home.” After that I think we were asked to sing at every public entertainment held in Mesa until after I was married. Lucy and Grandma Phelps bought us an organ which I learned to play by ear. Father and I played for the dances at Lehi a few times. I earned $2.50 over the Christmas holidays playing out there. I left my organ there during that time so I wouldn’t have to carry it back and forth.

Lucy and I joined the choir when I was sixteen, and I sang with them twenty years. I memorized 200 hymns besides the anthems we sang.

I well remember the first dress I made. It was a real pretty blue, and I wore a blue ribbon around my waist that Mother’s sister Anne LeSueur sent to me because they told her I looked so much like her.[8] In the summer of the year 1892, there was a conference held at Pine Top, and Mother and Aunt Clarinda, in company with quite a large group of Saints, attended; Brother Williams took them.[9] It took six weeks to make the round trip. Amy was four years old. While they were gone, I made Amy a dress. I made it a plain tight waist with a full skirt that came nearly to her ankles and so tight I could hardly fasten it. She had it on when Mother came, and when she saw her she began to cry. She said Amy looked like we had starved her.

One night at a dance, John S. Allen, known as Seymour, came into our lives. He rushed across the floor, came up to me and said, “Come on Caddie, let’s dance.” Then he saw his mistake and after an apology asked me to dance. From then on he never failed to dance with me and Lucy. Later on he began making regular visits to our home, but we did not know which one of us he was most interested in. We had a lot of good times together. One night he asked if he could take me home. Up to this time, he had never taken us any place. He had a lady friend and we were just side issues, but after this night we knew which were his favorites.

John S. [Allen] and I kept company for about nine months and were married October 2, 1895, in a quiet wedding in our home on the corner of Hibbert and East First Ave. Only close relatives were invited. The ceremony was performed by Bishop James Malen Horne.[10] We stood at the head of the table and guests were seated around it ready to partake as the ceremony ended. Mother and Lucy cooked a very fine dinner. When we went through the kitchen to be married, Mother and Lucy were standing by the stove. Mother was crying and Lucy was looking sad, but I couldn’t see anything to feel sad about. One week after we were married, we started to the St. George Temple in company with Eli and Medora Openshaw.[11] It took six weeks to make the round trip.

When we returned home, we started housekeeping in the two-roomed house built for Fannie and Warner.[12] It was here our first child, Ashael, was born July 31, 1896. At this time, fast meeting was held on Thursday afternoon and he was blessed by Grandpa Charles Hopkins Allen.

Blanche was born February 15, 1898. When she was four months old, John S. was called on a mission to the Southern States.[13] He left in June and I milked from eight to ten cows while he was gone, and my sister Esther stayed with me to help care for the babies. Mother was very good to me, and I wondered how I could get along without her. I did all of the sewing for her six daughters, Lucy, Hattie, Amy, Esther, Clara, and Gertrude. At this time, Lucy was working in Johnson’s store and did a lot to help the family.

I was blessed all the while John S. was gone, and we all enjoyed good health. When it was time for him to be released, I went to Utah in company with my parents and Father Allen and his wife Annie. Uncle Perry Bingham met us at Price, Utah, and took us to Vernal where I stayed until I heard from John S., and then I went to meet him in Cove three miles north of Richmond.

After we returned home, John S. and his brother Warner went in as partners and purchased eighty acres of land on Baseline Road. Hyrum Loren was born October 7, 1901, and Barbara was born October 5, 1903.

On July 26, 1907, Gove Liahona was born, and John S. went on another mission, this time to the Eastern States. I was left with more responsibilities and work, but Ashael was a big help, and one of my sisters stayed with me most of the time.

John S. came home in 1908 in June, and Mary was born September 1, 1910. On March 27, 1912, Eldred Phelps was born but only lived six weeks. This was the first real sorrow to come to us. On July 8, 1914, Russell Hoopes was born.

On December 2, 1915, Ashael left to go on a mission to the Southern States.[14] Ben Rich was born on June 5, 1916, and on November 5, 1917, Joseph Seymour was born while Ashael was still on his mission.[15]

When Joe was about eight months old, I took a little motherless baby Robert Southern (four months) to raise. I kept him nine months, and his aunt Mrs. Ellinbou wanted him so bad that J. S. told me I should not be selfish and keep him, so I let her have him.[16]

After several years, the depression came on, and we decided Seymour’s half brother Benjamin should live with us for a couple of years.[17] J. S. sent him on a mission. Also Charley, Seymour’s oldest brother, lived with us quite a bit.

Della, our youngest, was born November 11, 1920, four days after Loren had left for a mission in Louisiana. We struggled along for several years in the depression and decided to rent our ranch as the boys wanted to go to school and it was too much for Seymour to run it alone. We bought a home at 48 West Second Street in Mesa and lived there for more than a year.

John S. and his brother Jim took a job building a fence along the railroad. It was at this time when the next great sorrow came when Della died, November 21, 1925.

We sent Gove on a mission to the Eastern States, and in 1935 we sent Russell to the Samoan Islands to fill his mission. Before he returned home, we sent Ben to Argentina for a mission.

All our family members have very fine companions and have been sealed in the temple.[18] In all our family gatherings, they are with us 100 percent. We are very proud of our family and their families and always pray for their success in righteousness.

We had our Golden Wedding Anniversary, October 20, 1945, the first time all of our family had been together for a long time. For the celebration, Ashael came from a Spanish American mission, his wife Ida from Los Angeles, Russell from Kirtland, New Mexico, and Mary from Vallejo, California. We had a dinner at the ranch with our ten children, their companions, and twenty-seven grandchildren. It was a lovely time. After this celebration, Ida was called to labor with Ashael on his mission, and they took their son George with them.

Barbara Phelps Allen (center with accordion) and her Granny Band (left to right): Deborah Nelson, Julia Watkins, unidentified, Barbara Allen, unidentified, Lora Hancock, and Lizzie Rust. Photo courtesy of Barbara Nielsen.

Barbara Phelps Allen (center with accordion) and her Granny Band (left to right): Deborah Nelson, Julia Watkins, unidentified, Barbara Allen, unidentified, Lora Hancock, and Lizzie Rust. Photo courtesy of Barbara Nielsen.

Our mother was very strict about us attending our duties and being punctual. Because of this, the Sunday School superintendent called on me to be a substitute teacher while [I was] still quite young. When I was seventeen, I attended conference. At this time they reorganized the Stake YLMIA, and I was surprised when they sustained me as stake secretary. I served in this capacity for twelve years and under five presidents: Ann Eliza Leavitt, Jannett Johnson, Lula Macdonald, Fanny Dana and Mary Hibbert.[19] Soon after I was released, I was chosen as stake secretary for the Relief Society. I held that position for about six years and was released to be president of the Mesa First Ward Relief Society. I was in this position for about a year when we moved to Gilbert. There was no Gilbert Ward then, so we were in the Chandler Ward. After this I spent about sixteen years as president of the Primary in Chandler, Gilbert, and Mesa. I was president of the Primary at the same time I was superintendent of Religion Class in the Gilbert Ward. At this time, my son John was attending Gilbert High School, and he assisted me in Religion Class. We rented our ranch and bought a home in Mesa. At this time [about 1920], I was president of the Primary in Gilbert, and Bishop Haymore Sr. asked me to preside there until my daughter Barbara came.[20] This I did, and at this time I was made president of the Mesa First Ward Primary. I presided over both Primaries for about six weeks. I have been president of the Gilbert Ward Relief Society two different times, second counselor in the Mesa First Ward to Grace Nielson and second counselor to Adelaide Peterson in the stake Primary, and held several other positions.[21] Now at this time of 74, I am a Relief Society district teacher and a Guide teacher to four boys in the Primary of the Mesa Ninth Ward. I am very thankful for the many opportunities I have had to serve.

March 1942 was the Relief Society Centennial year, and the General Board requested that pioneer stories be brought before the public as much as possible. At that time, I was president of the Gilbert Ward Relief Society and read several good stories and decided to put them into a pageant. I had fine cooperation, and it turned out to be a success. We played it in six different wards. I also wrote an Easter and Aaronic Priesthood pageant which was very successful. In doing this work I received some of the greatest joy in my life. Another thing I enjoyed was putting on Primary programs with the children. There was a lot of work doing these things, but when it was over there was unspeakable joy that came to us seeing the happiness that came to the children.

The Lord has been good to me for which I am grateful. We have been relieved of pain through prayer and being administered to many times.[22] My first relief came to me when I was first married. I had an ulcerated tooth and thought I could stand it no longer. John S. administered to me and relief came instantly. Another time I was alone on the ranch with the little children. I became very sick; the pain in my head was so bad that part of the time I was not conscious. John was nine years old. He went off by himself and prayed for me. All at once a quivering feeling went through my body and with it the pain. I couldn’t account for it until he told me he had prayed for me. John had been instantly relieved twice when he had gathered ears.[23] One time when he had been helping the Chandler Ward pay off their debt on the piano by chopping maize and came home late, we found Loren crying with pain. As he drove the cows around the haystack, they loosened the derrick fork and it swung around before he knew it, striking him on the leg and puncturing his leg to the bone. The pain was so severe he could not stand to have us walk across the floor. He immediately called for his father to administer to him. The pain left as he took his hands from his head, and it never returned. For all of these and many more blessings too numerous to mention, I am grateful.

Barbara and Seymour filled an Indian mission at San Tan in the years 1948 and ’49.[24] They celebrated their Sixtieth Wedding Anniversary in 1955. She passed away January 31, 1957, in Mesa, Arizona.[25]

Ellis and Boone:

Barbara Allen not only began playing the accordion early in life, she was still playing it when a grandmother. She organized the Granny Band which performed at Relief Society and other civic functions. Daughter Blanche Allen Leavitt recalled that her mother “had a beautiful singing voice and a sharp ear for music and was always loyal to the ward choir. We could hear her calling us to come home, the oooos loud and clear, when we were over to the Plumbs’ [house] half a mile away. The ward parties were never complete without two gallons of Sister Allen’s super good ice cream. She was mindful of the poor and needy.”[26] Barbara Allen was also interested in her ancestors and compiled the book, Ancestors of the Children of Hyrum Smith Phelps.

Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen

Author Unknown, FWP

Maiden Name: Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes

Birth: September 9, 1847; Council Bluffs, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa

Parents: Warner Hoopes and Priscilla Gifford

Marriage: Charles Hopkins Allen;[27] June 15, 1864

Children: Charles Lewis (1865), Warner Hoopes (1866), Andrew Lee (1868), John Seymour (1870), Theodore Knapp (1872), Adelaide Cedilla (1874), Clarinda Knapp (1876), Elijah (1878), Priscilla (1879), Deborah (1881), Rebecca Hannah (1883), Julia (1885), James David (1887), Joseph (1889)

Death: November 13, 1889; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

The life of Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen, usually called Adelaide, is a series of faith-promoting incidents, which take their place alongside those of many other faithful pioneers who lived in the early days of the Church.

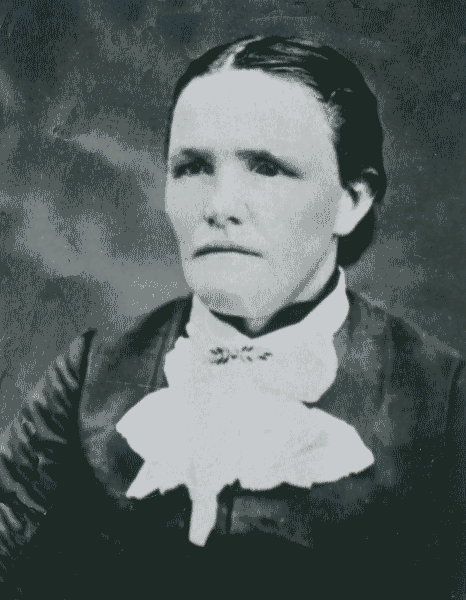

Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

She was the daughter of Warner Hoopes and Priscilla Gifford, and was born in Pottawattamie County, Iowa, September 9, 1847. If not the first, she was one of the first babies born in a humble pioneer wagon as her parents, in company with other Saints, were driven from their home in Nauvoo, Illinois.[28]

The early part of her life was spent amid the trials and tribulations experienced by thousands of other faithful Saints. Years afterward she related many of her interesting experiences to her children, one of which follows:

My father was a shoemaker by trade, and my mother was a woman of great faith and energy. At one time, about 1855, we moved into Buchanan County, Missouri, near St. Joseph, and worked at burning charcoal.[29] Here we became quite prosperous. My mother’s health was very poor, and they hoped that this change of climate would hasten her recovery.

Even in this part of the world, we found a strong sentiment against the Saints and their religion, and my father had an experience which taught him it was better to take counsel of those called of God. One night we entertained an Elder McGaw who had stopped at our place on his return trip from a mission to England. He told Father that he felt impressed that he, my father, should remove his family immediately to Florence, Nebraska, and there prepare to emigrate to Utah. He repeated the advice that night and again the next morning. After he had started away, he returned and advised him to go right away and leave his family to dispose of the property and follow after. But my father was loathe to leave this prosperous situation and heeded not the counsel. About a week later a non-Mormon family was burned in their house and the Mormons were accused of committing the deed. Four of the brethren were arrested but were proven innocent and released. However, the decisions of the court did not satisfy the hellish mob, which then made plans to kill them. The brethren were warned by a friend, but my father didn’t believe any harm would befall him. The sheriff of Buchanan County called for my father and offered him protection, and yet he refused to accept, for he “knew of no enemies,” he said. But after a few days when he had reconsidered, he began to feel a little uneasy, and one night he felt that he had better not be found at home. Consequently he left for the woods in back of the house, with the understanding that should friends come, my mother was to call him; if enemies should come she was to blow the dinner horn, signifying that he should hasten farther into the denseness.

Some time during the night my mother was awakened by some voices outside. She listened and recognized the voices of the mob making plans to take my father away. After they had stationed their guards at the doors and windows with the intention of “shooting him down” should he attempt to escape, she arose and taking the dinner horn, blew three loud blasts. The leader of the mob, thinking it a signal for him to return, entered and wrested the horn from her and blew it repeatedly. Finally my mother told him that the longer and louder he blew the horn, the farther and faster my father was going in the opposite direction. The mob grew more angry, but she told them that had they come like gentlemen, she would have called him and he would have returned. Furiously, they took to the woods where they hunted all night for Father and a Brother Lincoln but without avail. The next day they returned and tried to persuade my mother to “give up that terrible religion,” saying that if she would do so, she and her children would be well cared for. My mother’s answer was an inspiration to me. She said, “My husband and religion mean more to me than money, or anything money can buy.” They cursed her and used vile language as they took their departure. We children scattered hot coals in the yard in hopes that if they returned they would get burned.

The following night my father and Brother Lincoln returned and were taken to prison by the sheriff for protection from the mob. They remained there for ten months and were then proven innocent and released. Thus the money my father had accumulated was spent for lawyer fees and we were reduced to a state of poverty, all of which might have been averted had Father seen fit to take the counsel of the servant of the Lord. However, Mother was energetic and made willow baskets for us children to sell to help sustain our lives. Our last cow was sold to pay our steamboat fare to Florence, Nebraska, where we waited some time for my father to join us.

Elizabeth Adelaide inherited a great deal of energy and, like her mother, was ever ready to do things to help. She was about nine years of age when they left Nebraska to start across the plains to Utah. They had secured means to emigrate from her Uncle Hyrum Hoopes in Florence. She helped to care for her mother’s children, and the baby was her special charge, for her father was ill throughout the exodus and her mother had to drive while the children drove the loose cattle. A Brother Bovier said to Mother one night, “Sister Hoopes, if you could tie the calf at night, you would have the milk for your children,” but he didn’t offer to assist with the chore, so little Elizabeth Adelaide, always up and doing, undertook the task. She succeeded in getting the rope around the calf’s neck, but when it began to run, her strength was insufficient to handle the job; the calf pulled through the slough and brush and rough road until she had to let go. But she did her best, although help was necessary before she succeeded in tying the calf.

They arrived in Salt Lake City in 1857 and located soon after in Bountiful, where they lived for a short time, then moved to Cache Valley to locate permanently.[30]

Although her mother bore nine children, only four lived to grow to maturity. She was one of the older ones and was assigned to be her father’s helper. She herded the sheep and cattle, helped with the outside work in general, and helped with shearing as well as spinning, weaving, and sewing.

At the age of seventeen, she met Charles Hopkins Allen, who so admired her winsome and energetic ways that he desired her for a helpmate. Although he was seventeen years her senior, she seemed to share his feeling, for she consented to become his wife and they were married June 15, 1864.[31]

Often the Indians would enter the settlement and take liberties and commit depredations which were unwarranted. On one occasion, while her husband was away getting their winter’s supply of wood from the canyon, two Indians strolled into their yard and through the door, ordering Elizabeth to give them something to eat. Her nature was not of a nervous type, and so, while some women under like circumstances might have been frightened, she displayed no timidity. She was preparing them a “handout” when she noticed one’s gaze riveted on her rifle which was hanging on the wall. As he took a step toward the gun, she discerned his intention and drew the gun herself. He immediately grabbed a hatchet out of the wall and raised it, as she gave him an unexpected shove. It was so forceful that it landed him outside the door onto a board with a nail in it where he parted with a bit of his gaudy colored blanket. As is the nature of the [Native American], his admiration for her bravery recompensed him for the humiliation he had received, and they took themselves off without giving her any more trouble.

After a few years of residence in Richmond, Utah, they moved three miles north into Cove where they made themselves a very beautiful home.[32] While living there, five other children were born to them—four girls and one boy.

Elizabeth Allen was of a very friendly disposition and her doors were always open to welcome her friends and relatives. The young people in the community felt free to mingle with her and her children and came and went as if it were their home. If the number of beds was insufficient to accommodate all the visitors, pallets were made on the floor and none seemed to find them uncomfortable.

She always found pleasure in having the elderly women in her home and sought to make them comfortable. She felt that she was repaid by the faith-promoting stories they told her children. She promoted the spirit of home entertainment to keep the children under the family roof. She possessed the spirit of home evening long before the Prophet of the Lord recommended the practice throughout the Church. “Playing Primary” was a delight for which the children anxiously and conscientiously prepared to make a success. Each member, from the oldest to the youngest, on such occasions, took his part and felt it a dignified opportunity to make others happy. Should it happen that Grandma Alverston or Grandma Brady or any other visitors were present, they were given a part on the program and felt it an honor to participate.

The ability to “do things,” displayed in her youth, did not desert her in later life. Situations often arose which gave her ample opportunity to use that ability. On one occasion when her husband and his brother were on a freighting trip leaving her and her sister-in-law to keep up the home, the women decided that they must have some meat to eat. Mary said she would knock the pig in the head if Elizabeth would cut its throat. They agreed, and when the water was hot and everything was ready, Mary took the ax and entered the pig pen. She raised the ax and let it fall upon the head of the pig, but her strength was not great and she had failed to extinguish the life of the animal, and it ran crazily around the pen squealing. Elizabeth saw Mary hurriedly climb from the pen and heard her screams, and then she came running to the rescue. Carrying with her a butcher knife, she heroically entered the pen and cut the pig’s throat, thus ending the animal’s life and stopping its suffering.

We women of our modern days cannot seem to understand just how our mothers and grandmothers played the part of manufacturer in addition to their everyday household duties and the rearing and caring for their large families. Elizabeth Allen was one of the women who were not strangers to the spinning wheel and the loom. Like many others in those days, the late hours of many a night found her seated at the spinning wheel or loom, busily engaged in preparing raiment for her children, her mate, and herself while the family was peacefully sleeping.

Often she would do two duties at the same time, or as we often say, “kill two birds with one stone.” If she found a few minutes to rest her weary limbs, her fingers were rapidly wielding the knitting needles, shaping the yarn into stockings for the winter’s use. So proficient and dexterous did she become that she made a stocking while en route to Relief Society and Thursday morning Fast Meetings.

Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen. Although undated, it appears that this photograph illustrates maternity fashion of the nineteenth century. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen. Although undated, it appears that this photograph illustrates maternity fashion of the nineteenth century. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

About the year of 1882, President Young had been calling Saints to dispose of their homes in the north and to emigrate to Arizona and other southern places to start new settlements so as to make room for the increasing population there. The spirit of going to the new country seemed to grip the minds of many, and because Brother Allen had been suffering with rheumatism, he persuaded his good wife that it would be to their advantage to go to Arizona, the land of sunshine. He had learned of many of the virtues of that sunny land from his brother Elijah who was a member of the Mormon Battalion and had passed through there in [1846].[33] Therefore, early in October 1882, with two wagons having four horses to each and a light hack with one team of nice fat horses, they left their home in Cove and began their travels to the land of Arizona. Although she loved her home very dearly, Elizabeth Allen entered into the project with a loyal acquiescence, for the health of her husband meant much to her and she knew that they could build again as they had done before. Her services were required to drive the team on the hack as the bigger boys and the father had to handle the other two outfits. During these six weeks of traveling, her knitting needles were ever busy, as she permitted her horses to follow along behind the wagons.

On November 13, 1882, they entered what is now Mesa, Arizona. The first friends to meet and welcome them were the Stewarts, Standages, and Pews, all of whom they had previously known in Utah. They camped for a few days but soon bargained with Henry J. Horne for a quarter section of land on which there was already built an adobe house with one room.[34]

The following summer, in July, another baby girl was born, and she was but a few weeks old when a plague of smallpox increased the trials of the faithful pioneers in Mesa. The Allens continued to exhibit their ever-ready faith and courage as they went out among the sick, he to administer by the power of the Holy Priesthood and she to help in the many ways a willing and practical nurse can help in times of sickness. Although they and three of their children were exposed, none took the dreaded disease. Often times when she could not be spared from her home, she took into her home duties which would relieve the suffering of responsibility. When the Stewarts were stricken with smallpox, she took their three small children and cared for them until the parents died.[35] That summer was a very sad one, for each week found the little colony decreased by two or more of its inhabitants. No doctors were available, and the Saints were forced to rely on the help of the Lord and their own experiences. These sad experiences and trials seemed to draw the people nearer together and to unite them in the faith.

The following few years brought three more children into the Allen home. When the last, which was the fourteenth, was born, November 13, 1889, Elizabeth Adelaide passed through the valley of the shadow of death into the Great Beyond to rest from the constant struggles of this earthly life, and to await the reward of the faithful. She had often expressed her desire to visit her old home in Utah, but for some good reason, no doubt, she was denied the realization of this.

Her entire life was devoted to the service of others. Like the Master Himself, she visited the weak and suffering, the poor and the needy, and the widows and the fatherless to administer to their needs. And in doing this, she never neglected her devoted husband and loving children.

She was active in church affairs. Being a natural-born teacher and disciplinarian, she was ever successful. She possessed unlimited faith, courage, and charity. She was companionable and cheerful, radiating her goodwill wherever she went. She gave up her life to give life to another. Surely it must be said of her that inasmuch as she did it unto the least of His, she did it unto Him. Her influence on her family lives on forever.

The expression of love and esteem which others held for her was manifest by the attendance at her funeral services. Henry Rogers said, “The sick, the needy, and those bowed down in sorrow will miss Sister Allen most.” Sixty carriages followed her body to the cemetery, which was the largest funeral procession up to that time.[36] Her last conscious request was that tithing be paid on the butter she had sold that she might feel that she was square with the Lord.

Ellis and Boone:

Adelaide’s home was a gathering place for the young folks who often spent the night bedded down on the floor. She enjoyed music, including popular ballads of the day such as “Polly Van,” “Joe Bowers,” “Captain Jinks,” and “Vacant Chair.” She also would put up five gallons of grape jelly, honey, and barrels of dried grapes.

She frequently drove, unescorted, in a buggy pulled by a span of little mules named Jack and Molly. The mules were purportedly frightened of Indians. Upon smelling one, the mules would prick up their ears, lift their noses, and then break into a dead run. Because Mesa was located near a reservation on the Salt River, encounters were frequent. During these episodes, Adelaide would simply brace her feet and push on the brake. Though she frequently had small children with her, she never experienced an accident because of such encounters.

Notes

[1] “Hyrum Smith Phelps,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:138–39; “Sketch of the Life of Hyrum Smith Phelps,” in Clayton, PMA, 387−92.

[2] Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps, 533.

[3] Although also known as Seymour, most of the references here call him “John S.” “Life History of John Seymour Allen,” in Clayton, PMA, 16−20.

[4] 1920 census, John S. Allen, Chandler, Maricopa Co., Arizona.

[5] Sunday School, both within and outside The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has always been for the instruction of children. Primary was instituted as a weekday class for Latter-day Saint children in 1878 (see n. 83 for Clara Gleason Rogers, 590). In 1980, Primary was moved to Sunday, replacing Junior Sunday School. Naomi B. Shumway, “Primary,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1146–50.

[6] Hyrum Smith Phelps, along with five other men, was accused of unlawful cohabitation in April 1885 and was given a lenient sentence of ninety days in the Yuma Penitentiary. He was released on July 12, 1885, and, as he continued to live with his two wives, he was advised to move to Mexico. He traveled to Colonia Juárez in 1887 but did not like conditions and returned home to Mesa where he died on April 23, 1926. Boone and Flake, “The Prison Diary of William Jordan Flake,” 145–170.

[7] Charles Innes Robson (1837–94) lived in Mesa and was married to Francelle Pomeroy (1845–94). He was president of the Maricopa Stake from 1886 to 1894. “Charles Innes Robson,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:558–59.

[8] Anne Bingham (1860–1910) was married to William F. LeSueur (1856–1941) and lived in the Eagar/

[9] The conference took place on July 4, 1892. Clarinda Bingham (1850–1927) was one of the wives of Hyrum Smith Phelps. McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 170.

[10] James Malen Horne (1866–1949) came to Arizona from Paris, Idaho. “James M. Horne,” in Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:142; AzDC.

[11] Eli Carlos Openshaw (1872–1957) was married to Medora Brimhall (1874–1957). He was a son of Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw, 502.

[12] Fannie Busby Peterson (1871–1929) was married to Warner Hoopes Allen (1866–1932), an older brother of John Seymore Allen. “Warner Hoopes Allen,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:142.

[13] John Seymore Allen was set apart on June 15, 1898, and arrived at Chattanooga, Tennessee, on June 25. He was released on August 20, 1900, and arrived home on August 26. “Southern States Manuscript History and Historical Report,” LR 8557 2, Reel 1, CHL.

[14] Charles Ashael Allen was called to the Southern States Mission on December 2, 1915, and arrived at Atlanta, Georgia, on December 12. He was released on July 18, 1918. “Southern States Manuscript History and Historical Report,” LR 8557 2, Reel 1, CHL.

[15] Naming a child after a mission president was not uncommon. Ben E. [Benjamin Erastus] Rich (1855–1913) was mission president from June 10, 1898, until one week before his death. His assignment was always the southeastern part of the United States, but the mission assignment went through several changes—from Southern States to Middle States to Southern States and finally Eastern States. David F. Boone, “Ben E. Rich,” in Garr, Cannon, and Cowan, Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1019; “Southern States Manuscript History and Historical Report,” LR 8557 2, Reel 1, CHL. When Charles A. Callis was president of the Southern States Mission, the humorous observation was made that the route of conferences could be seen in the names given to boys born shortly after the conferences were held. David F. Boone, “President Charles A. Callis in the Southern States Mission: The Watershed in the Success of the Latter-day Saints in the U.S.,” paper given at Mormon History Association Symposium, May 11, 1984.

[16] This was Robert Iver Ellingboe, born February 8, 1918, at Gilbert, Maricopa Co., Arizona; his parents were Iver I. Ellingboe and Mary Lee Southers. AzBC.

[17] Arizona’s economy, particularly the farming and ranching communities, struggled during the early 1920s. Both ranchers and cotton farmers suffered from a severe drought from 1918 to 1921. By 1928, both the mining and agriculture sectors were starting to prosper again. Then the stock market crash of October 24, 1929, erased all gains, and the Great Depression began. Sheridan, Arizona, 253.

[18] To Latter-day Saints, a temple sealing refers to the uniting of a man and woman in marriage with the relationship between them and their children lasting forever. Paul V. Hyer, “Temple Sealings,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1289–90.

[19] Ann Eliza Hakes Leavitt, 406; Jannetta Isabella Hawley (1864–1934), wife of Brigham Moroni Johnson (moved to San Diego, California); Lula Jane Cluff (1869/

[20] Arthur Samuel Haymore (1878–1967) was born in Utah but went with his family to Mexico where he married Abby Jane Scott in 1898. The family left Mexico permanently about 1914 and settled in Mesa. 1920 census, Arthur L. [sic] Haymore, Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona; “Arthur Samuel Haymore,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:524.

[21] Emma Grace Rogers (1891–1973), wife of Hyrum Nielson; Adelaide Cedilla Allen (1874–1963), wife of Charles Peterson.

[22] The ordinance of blessing the sick is generally performed by two Melchizedek Priesthood bearers and often (although not mentioned here) consecrated olive oil is used. Nephi K. Kezerian, “Blessing the Sick,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1308–9.

[23] Although this may merely mean ear infections, it seems likely that she was talking about infections so bad that the eardrum breaks and drains. She is probably using “gather” to mean to fester and come to a head, as a boil does.

[24] The sketch for John Seymour Allen lists two missions (each two years long) at San Tan beginning in 1943. Clayton, PMA, 19.

[25] This is the sketch that Allen wrote about herself for her book. RFC or one of Barbara’s descendants added the last paragraph when it was included in PWA. Allen, Ancestors of the Children of Hyrum Smith Phelps, 65−69.

[26] Personal communication, D. L. Turner.

[27] “Charles Hopkins Allen,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:140–41; Turner and Ellis, Latter-day Saints in Mesa, 23.

[28] This statement seems to be confusing the birth date with the exodus of the poor from Nauvoo in September 1846.

[29] Charcoal was produced by heating wood (or other carbon-based materials) in the absence of air, usually in a pit. The resulting charcoal burned hotter and with less smoke than wood. The Hoopes family worked for several years in Missouri, accumulating funds to travel further west. When I. E. Solomon came to Arizona, his plan for financial success was to begin with producing charcoal from the mesquite trees in the Gila Valley and sell it to the mine at Clifton. Ramenofsky, From Charcoal to Banking, 50–51; 1850 census, Warner Hoope, Preston, Platte Co., Missouri.

[30] MPOT, however, lists the Hoopes family as coming to Utah in 1859 with the Redfield and Smith Freight Train.

[31] They were married in Richmond and sealed in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

[32] Charles Hopkins Allen served as president of the Cove Branch.

[33] Elijah Allen (1826–66) was a member of Company B in the Mormon Battalion and after discharge chose to remain in California. He was in Salt Lake City by 1853. Ricketts, Mormon Battalion, 169, 283; “Elijah Allen,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:581–82; 1860 census, Elijah Allen, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah.

[34] Henry James Horne (1838–1927) was married to Mary Ann Crismon (1842/

[35] These children may be those of Eliza Barnett Stewart, the second wife of Alvin F. Stewart. In 1883, she had five children living (ages one to fifteen). The oldest, Estrella, died of smallpox, and four children survived their mother’s death. It may be that Dora (age sixteen) was quarantined, sick with smallpox, and the three children mentioned here were Ray (age eight), Alva (age six), and Edward (age one). However, their father did not die until 1905. For information about deaths during the smallpox epidemic, see comments by Ellis and Boone in Julia Christina Hobson Stewart, 699.

[36] Additions from Elizabeth Adalaide Hoopes Allen, FWP, ASLAPR. Henry Clay Rogers was the husband of Emma Higbee Rogers, 599.