The Temple Site

Richard O. Cowan and Robert G. Larson, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 17–40.

1918 End of World War I brings decade of growth in California

1927 First Northern California stake organized at San Francisco (July 10)

1928 George Albert Smith attends Boy Scout meeting in San Francisco (April)

1933 California members make excursion to Salt Lake Temple (June)

California members make excursion to Arizona Temple (December)

1934 David O. McKay visits future Oakland Temple site (January 21)

Oakland Stake organized (December 9)

1942 Construction restricted because of World War II (March)

First Presidency authorizes purchase of Oakland Temple site (November 16)

1947 Key parcel purchased giving access to temple site (August)

The end of World War I brought to the United States a mood of celebration and optimism that lasted a decade. During these years, record numbers of Americans—including Latter-day Saints—sought to fulfill their dreams in the Golden State.

Church Growth and the Creation of Stakes

Following the end of the war, Church membership in California began to grow. Many Latter-day Saints left Utah and surrounding areas in quest of better economic opportunities, additional education, or just a warmer climate in the Golden State. The number of California Latter-day Saints increased more than fivefold, from 3,967 in 1920 to 20,599 in 1930. In fact, Latter-day Saint growth was greater than that of the population as a whole; the Mormon share rose from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 250.

Church growth in California occurred in a logical sequence. In areas where membership was sparse, small Sunday Schools were established—often meeting in members’ homes. As these Sunday Schools grew, they eventually became units called “branches,” typically with a few dozen members. When branches within a given district reached about 200 members and had adequate leadership, they could become “wards” and be grouped into a “stake of Zion.” The term stake came from Isaiah’s analogy of the Lord’s people being accommodated in a large tent whose stakes, or surrounding tent posts, were sources of strength and stability (see Isaiah 54:2). Church growth was faster in Southern California, so the first modern stake in California was organized in Los Angeles in 1923.

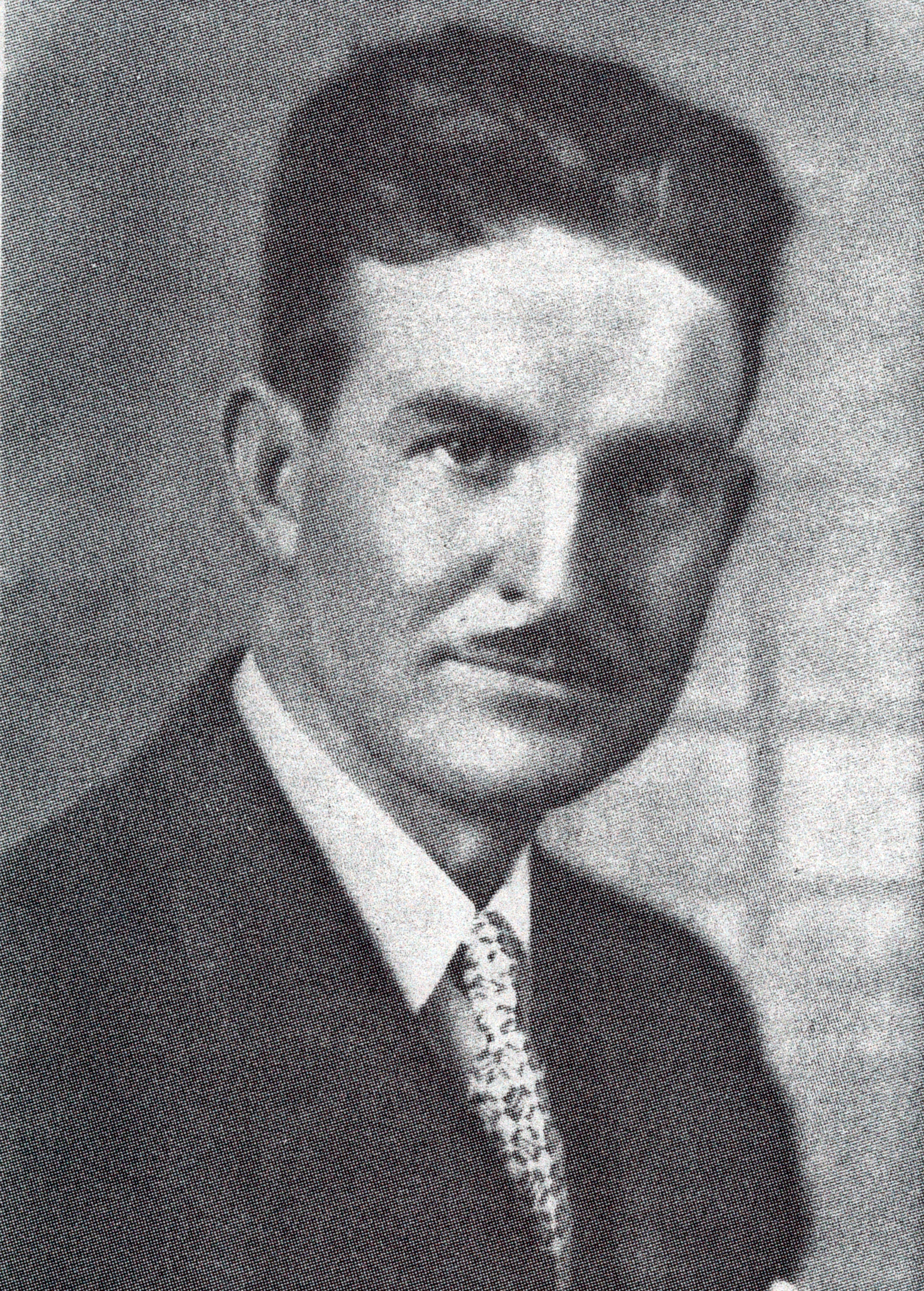

W. Aird Macdonald. Photo courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

W. Aird Macdonald. Photo courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

By 1926, there were 1,500 members in the Bay Area. At a conference on July 10, 1927, Apostles Rudger Clawson and George Albert Smith organized California’s second stake, the San Francisco Stake. W. Aird Macdonald, president of the Oakland Branch, was called to preside over the new unit. It had a membership of over 3,000 and consisted of the Berkeley, Daly City, Dimond, Elmhurst, Martinez, Mission, Oakland, Richmond, San Francisco, and Sunset Wards, plus a few smaller branches—all in the central Bay Area.

President Macdonald, a native of Arizona, had resided in the Bay Area since 1911, where he had been an artist, writer, and photographer for local newspapers—including the Oakland Tribune and San Francisco Chronicle. In later years, he became an insurance agent, a member of the California State Board of Equalization, and a member of the prestigious Commonwealth Club.

Elder George Albert Smith’s Vision

Ever since Brigham Young prophesied that “in process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord,” [1] California Saints had looked forward to having a temple in their area. While the early Church in the Golden State had not been strong enough to warrant the construction of one of these sacred structures, the many faithful Latter-day Saints now coming to California made the building of a temple more plausible.

In the early 1920s, there were six functioning Latter-day Saint temples—one in Hawaii, another in Alberta, and four in Utah. During the decade, another temple would be dedicated in Arizona. This meant that Latter-day Saints in the Bay Area had to travel over 900 miles on winding roads over the mountains and through the deserts to reach the nearest temple in Salt Lake City—a trip that would have required at least two long days. Church members in Northern California could only hope that sometime in the future a prophet would announce a temple for them. At this time, Heber J. Grant was President of the Church. He visited California regularly, so was well acquainted with conditions there.

Temples in the Western United States

Temples in the Western United States, created by Think Spatial BYU

Temples in the Western United States, created by Think Spatial BYU

Elder George Albert Smith was an avid Scouter. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc

Elder George Albert Smith was an avid Scouter. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc

In 1921, George Albert Smith, one of the Twelve Apostles, became superintendent of the Church’s Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association. The Church had been one of the first to adopt the program of the Boy Scouts of America, and this responsibility now fell within Elder Smith’s assignment. “He subscribed to the aims of Scouting to foster loyalty to God and country and to develop physical, mental, and moral strength. And he saw in the Scout goal of doing one good deed each day a strong incentive for Christian living.” His biographer noted that George Albert Smith was proud to wear his Scout leader’s uniform whenever he could. “To see George Albert decked out in full regalia left no uncertainty about his commitment to Scouting nor about his genuine enjoyment of the key role he played in it.” [2]

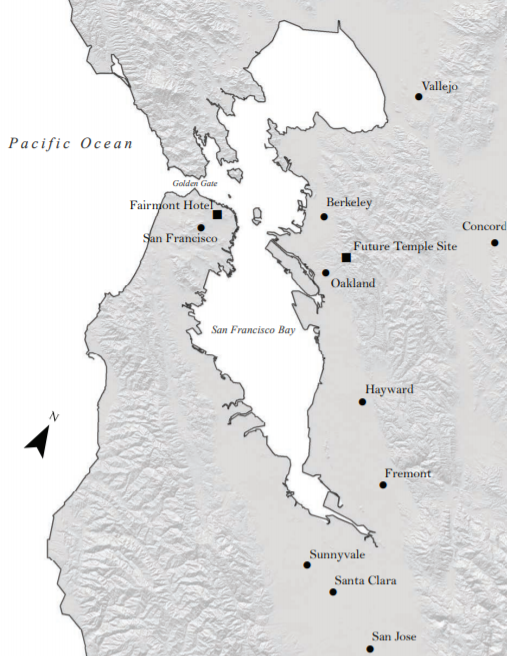

In April 1928, Elder Smith was in San Francisco attending the eighteenth annual meeting of the Boy Scouts of America’s national council. On that occasion he met with President Macdonald, whom he had installed as the new stake president just nine months earlier. They met at the Fairmont Hotel high atop San Francisco’s Nob Hill. Macdonald later reported his memory of the occasion:

From the Fairmont terrace we had a wonderful panorama of the great San Francisco Bay, nestling at our feet. The setting sun seemed to set the whole eastern shore afire, until the Oakland hills were ablaze with golden light. As we admired the beauty and majesty of the scene, President Smith suddenly grew silent, ceased talking, and for several minutes gazed intently toward the East Bay hills. “Brother Macdonald, I can almost see in vision a white temple of the Lord high upon those hills,” he exclaimed rapturously, “an ensign to all the world travelers as they sail through the Golden Gate into this wonderful harbor.” Then he studied the vista for a few moments as if to make sure of the scene before him. “Yes, sir, a great white temple of the Lord,” he confided with calm assurance, “will grace those hills, a glorious ensign to the nations, to welcome our Father’s children as they visit this great city.” [3]

Elder George Albert Smith was on the front row, third from the right. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder George Albert Smith was on the front row, third from the right. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

President Macdonald also recalled that “there was no preliminary discussion of temples. The incident came quite unexpectedly but it was very impressive. The [other] matters we were discussing were quite forgotten in the sudden vision that came to him.” [4] In coming years, reports of this vision were cited over and over by eager Bay Area Saints.

Setting of Elder George Albert Smith’s Vision, created by Think Spatial BYU.

Setting of Elder George Albert Smith’s Vision, created by Think Spatial BYU.

Salt Lake Temple, photo by LeRay Swainston. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2013.

Salt Lake Temple, photo by LeRay Swainston. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2013.

Saints’ Interest in Temple Service

Long before the Bay Area Saints would have a temple of their own, their interest in temple activity was strong. In June 1933, for example, eleven members of the San Francisco Stake traveled to the Salt Lake Temple, where four received their endowments. While there, the group performed 188 baptisms and 64 endowments for the dead, as well as sealings for 150 families. They reported that “a feeling of spiritual fellowship characterized the entire excursion,” and their accounts prompted others to participate in the next one. [5]

On the day after Christmas that same year, 124 Saints boarded a chartered train in Oakland for the trip to the Arizona Temple in Mesa. They thought of themselves as “pilgrims” on a spiritual journey. Upon arriving there, they were greeted by a brass band and by a “great crowd” of local Saints who would provide hospitality. This time 811 baptisms and about 500 endowments were performed. Two testimony meetings were conducted in the temple. The temple president acknowledged that this was the largest group that had come from the farthest distance to the temple in Mesa. The group was back in Oakland on the morning of January 2, 1934. “Afterwards many testified that the evil tendencies seemed to be purged from their natures, and nothing but good will and love for fellowmen and God remained.” [6]

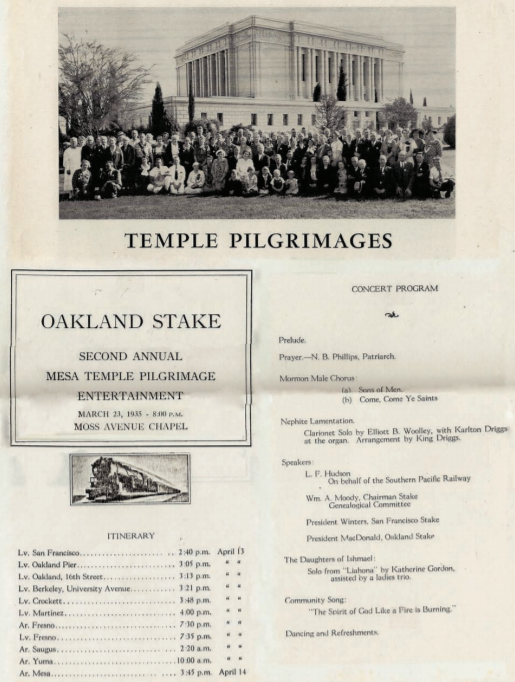

The second annual temple excursion to the Arizona Temple was scheduled for the week before Easter in 1935. An article in the Messenger, the Bay Area Mormon newspaper, indicated that one participant who had been in the original excursion regarded it as the “trip of trips.” The article announced that a “special train” would make various stops in the Bay Area to pick up passengers, and that the Sacramento and Gridley Stakes were also invited to participate. The group went and returned “on this train singing and rejoicing like Crusaders of old, but without sword or lance.” [7] A member of the Oakland Stake presidency affirmed, “The spiritual uplift that was manifest as a result of a Pilgrimage of last year is still in evidence in the Stake, and we, the Stake Presidency, feel that no better movement could be inaugurated to put spiritual life into our people than a continuance of these Temple Excursions.” [8] Committees provided detailed checklists and conducted a series of activities in preparation for these excursions. [9] A kickoff meeting held in Oakland on March 23 featured original musical numbers, remarks by Church leaders, greeting from a Southern Pacific Railroad official, and the singing of “The Spirit of God.” The evening concluded with dancing and refreshments. [10] Participants in these excursions recalled how “it was a joy on that train to walk from car to car and find in every seat well-known church members with but one thought—temple work we were to do in the lovely Mesa Temple.” [11]

Printed program at pre-excursion meeting. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

Printed program at pre-excursion meeting. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

In 1937, a group went to Mesa by a chartered Greyhound bus. “Every seat was filled with church members and happy hours of conversation passed the time rapidly,” one member recalled. “Several brethren brought musical instruments, such as guitars and mouth organs, which furnished accompaniments for group singing of old favorites.” [12] In later years, similar excursions were more regular, but still eagerly anticipated, events.

In addition to these organized excursions, individual Church members made hundreds of trips to Arizona and Utah to do temple work. During the Depression, however, the expense of long-distance travel kept the California Saints yearning for their own temples.

Two tragedies during these lengthy trips also underscored the desirability of having a temple closer. In 1934, a bus chartered by a Southern California ward overturned on its way back from Mesa, killing six. Another heart-rending tragedy occurred three days after Christmas in 1938: two little girls and a teenage boy were traveling with their family by car to take part in sacred family ordinances at the St. George Temple. All three children were killed in a car accident on the winding road through central California’s San Marcos Pass. [13] News of these tragedies undoubtedly spurred the efforts of local leaders to find a suitable temple site.

“Hill Watchers”

President Heber J. Grant (center) with counselors J. Reuben Clark Jr. (left) and David O. McKay. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

President Heber J. Grant (center) with counselors J. Reuben Clark Jr. (left) and David O. McKay. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

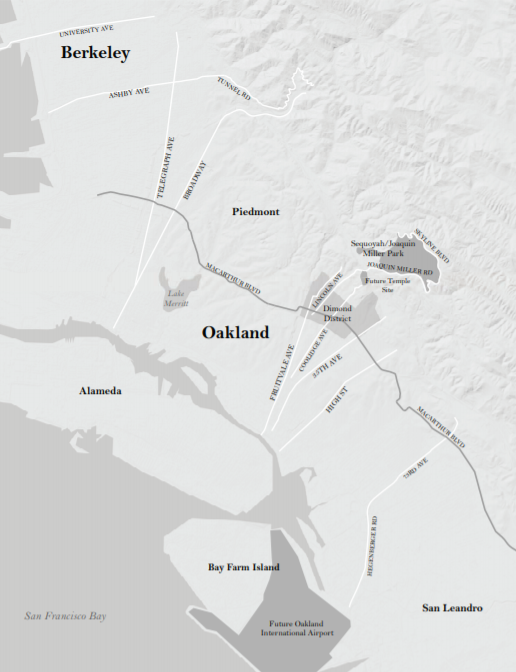

Meanwhile, the idea of a temple in Oakland undoubtedly remained very much on President Macdonald’s mind. On January 21, 1934, Elder David O. McKay of the Quorum of the Twelve presided at a conference of the San Francisco Stake, held in Oakland. [14] President Macdonald later recalled how the Apostle asked to see the area “where Brother Smith had envisioned a temple.” Macdonald accompanied him to the place where the Oakland Temple now stands “high above the Dimond district off Mountain Boulevard.” [15] Later that same year, a committee was formed to locate the temple site. It was headed by Eugene Hilton, an educator who served as Macdonald’s counselor in the stake presidency (and who would become stake president in 1937). Other members were Delbert F. Wright (who would become the temple’s first president thirty years later) and real-estate developer Ambrose B. Graham. [16] At the Church’s general conference in October of that same year, Elder McKay became the second counselor to Heber J. Grant in the First Presidency.

The Church continued to grow in the Bay Area, and by late 1934 the San Francisco Stake had 5,000 members. On December 9 of that year, the stake was divided under the personal direction of Church President Heber J. Grant, and W. Aird Macdonald became president of the new Oakland Stake. At the meeting, President Grant contrasted the current attitude toward Church members with what he had experienced on his first visit to California fifty years earlier: “The people on the train avoided us when they discovered we were ‘Mormons.’ [Today] it is a certificate of character . . . to be known as a Mormon because of the splendid tenets of our religion and the manner in which its members live up to them.” [17]

Postcard view of Lake Merritt, Oakland, ca. 1911. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

Postcard view of Lake Merritt, Oakland, ca. 1911. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

Early view from Temple Hill. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

Early view from Temple Hill. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

The Oakland Temple site committee pursued the task of locating and acquiring the site envisioned by Elder George Albert Smith years before. As they searched, they were enthusiastically aided by the local chamber of commerce and city officials. The committee looked over several possible sites. Even though the city of Oakland offered two locations free of charge, and while one “on the shores of Lake Merritt was seriously considered,” [18] a particular spot in the hills always impressed the committee as “the one.” [19] Unfortunately, it was not for sale. They also faced resistance from leaders in Salt Lake City after the purchase of the Los Angeles Temple site in March 1937, because the Church was reluctant to build two temples in California at the same time.

The committee suspended its work, but President Hilton admonished, “Let us patiently wait our time and keep silent concerning this preferred site. Let us also watch and pray that we may yet obtain it.” [20] Concerning the hoped-for purchase, one Bay Area Saint reflected, “Always it has had that etherial [sic], mysterious quality which is the stuff of which dreams are made, enabling it to appear, disappear, reappear, and to seem ever just beyond reach, too good to become true.” [21]

At first, President Hilton and his counselors had seen their preferred site only from a distance, but finally they went right up onto it and looked it over. President Hilton then invited the bishops of the different wards to go with them to see it. Vinal Mauss, a member of the Oakland Ward bishopric, recalled, “I was invited to go. We went up Coolidge Avenue as far as Coolidge went at the time, and climbed over a fence, and climbed a hill. And we were all just so thrilled with that view and the site there that we all gave approval without any question. This would be the spot.” They recalled George Albert Smith had seen those hills and thought someday there should be a temple there. The group therefore concluded, “Well, that’s the spot. That’s where it’s going to be.” [22] However, when the owner of the property died, his heirs decided to maximize their profits, so they did not sell the hoped-for site to the Church, but rather to real-estate developer J. F. Patterson and his wife, Alice. [23]

Eugene Hilton. Photographer unknown. Originally in Triumph, published in 1959 by the Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, and Walnut Creek Stakes.

Eugene Hilton. Photographer unknown. Originally in Triumph, published in 1959 by the Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, and Walnut Creek Stakes.

Acquiring the Choice Site

The attack on Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7, 1941, once again propelled the United States into war. The coming of World War II disrupted many Church activities. One of the war’s few favorable impacts, however, was to finally facilitate the acquisition of that longed-for special hill.

Oakland Church leaders kept alive their hope for a temple despite wartime challenges. When he was in Utah during July 1942, stake president Eugene Hilton contacted J. Reuben Clark, First Counselor in the First Presidency, and found him to be “encouraging.” The following month, Elder John A. Widtsoe of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles visited with Hilton and was “enthusiastic about the whole Bay Area.” [24]

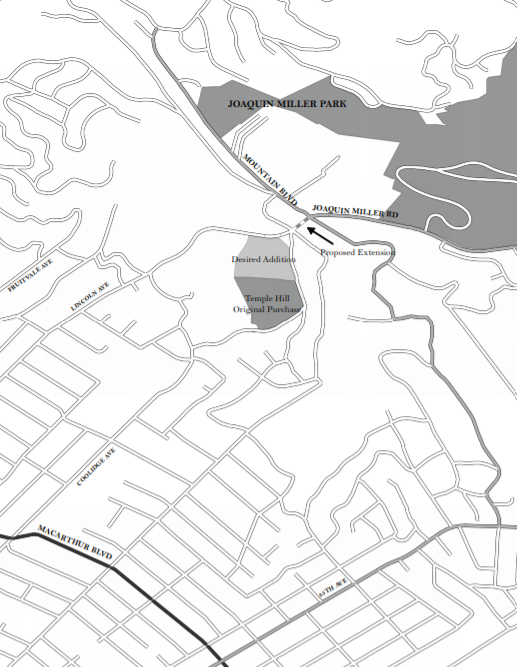

Temple Hill Neighborhood. Created by Think Spatial BYU.

Temple Hill Neighborhood. Created by Think Spatial BYU.

However, on January 16, 1942, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt had created the War Production Board to regulate the allocation of materials regarded as critical to the war effort. Starting in March, the use of most metals in nondefense construction was prohibited, and the building of new housing was allowed only to accommodate war workers. As a result, new construction during the first six months of 1942 was only one-third as much as during the same period in the previous year. [25]

It was in the climate of these increasing government restrictions that A. B. Graham, member of the original site-selection committee, went to President Hilton, who had chaired that same committee, with some good news: “It looks like our chance has come.” [26] Graham informed Hilton that because of the war, the frustrated owner of the choice hill—who had city, county, and even state approvals for his planned subdivision of luxury homes—could not proceed, as the needed construction materials had suddenly become unavailable. [27] He had therefore offered the entire 14.5 acres to Graham for $18,000 (about $250,000 in today’s money), which Oakland’s stake leaders regarded as “a most marvelous bargain.” [28]

Graham’s wife was affiliated with the Montclair Realty Company, which was described as the “Pioneer of the Piedmont Hills,” [29] so she may have played a key role in these negotiations. “That is wonderful news indeed,” the stake president responded. The offer may have represented a test of Brother Graham’s faith, because he was only partially involved in Church activity at that time and could have used the property for his own advantage. [30] President Hilton inquired, “Do you plan to buy it for your own use?” “I want the Church to have the first chance—but we will have to act fast,” Graham stated.

President Hilton concluded, “This is most important. It is an answer to our prayers. We won’t wait for the mails. I will go directly to Salt Lake tonight.” [31] In a letter to Church leaders dated September 15, 1942, he also urged purchase of the property.

The First Presidency agreed to send someone to look at the proposed site. However, one delay after another—including major responsibility for the October general conference—kept David O. McKay from coming for nearly two months. The staunch “hill watchers passed many anxious hours,” as the owner was on the verge of selling the property to others who were offering him more money. [32] Fortunately, Graham’s diplomacy and friendship with the owner were rewarded, as the owner delayed selling the property and it was still available when President McKay finally arrived. “Looking back, it may seem strange that a successful business man would not optimize his profit and accept the highest offer,” one local Saint, Arthur Coombs, reflected. “But to the faithful, it is obvious that the hand of the Lord was directing these matters.” [33]

Top: Temple Hill at the time it was purchased. Photo by Wendell Jackson, in Wright History. Courtesy of Robert Larsen. Bottom: View of Oakland from Temple Hill. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

Top: Temple Hill at the time it was purchased. Photo by Wendell Jackson, in Wright History. Courtesy of Robert Larsen. Bottom: View of Oakland from Temple Hill. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

President McKay was “enraptured at what he saw” and promised to recommend its purchase. From that time on, the Saints confidently referred to the site as “Temple Hill.” [34]

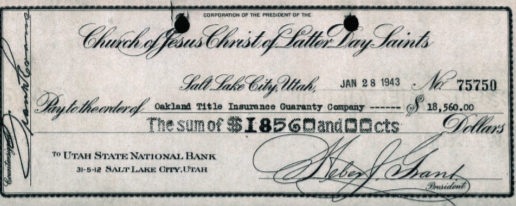

On November 16, Presidents Grant and McKay wrote to Brother Graham, who was handling the negotiations: “We have concluded to purchase the fifteen acres.” They sent a check of $100 “for assurance of good faith.” The balance of the $18,560 purchase price was sent, and the “indenture,” or agreement, was drawn up on December 15, 1942; signed January 28, 1943; and officially recorded February 2. [35] “The transaction was speedily concluded,” exulted President Hilton, “and the temple site was ours!” [36]

President Heber J. Grant announced the purchase a few weeks later at the April general conference: “I am happy to tell you that we have purchased in the Oakland area another temple site. The negotiations have been finally concluded and the title has passed. The site is located on the lower foothills of East Oakland on a rounded hill overlooking San Francisco Bay. We shall in due course build there a splendid temple.” [37]

On Easter Sunday three weeks later, a “goodly number from the wards throughout the stake” gathered on Temple Hill at 2:30 in the afternoon. After the group sang “The Spirit of God,” they heard remarks from President Hilton and his counselors, Glen Harmon and Delbert Wright. They encouraged their listeners to prepare spiritually and financially for the time when the temple would be built there, and to get their family history records in order. Concluding his account of this gathering, William Evans paraphrased Isaiah 52:7 saying, “How glorious upon the hill top is the name of Him who publisheth peace and prepares mankind for eternal salvation.” [38]

Original check paying for Temple Hill, signed by Heber J. Grant, January 28, 1943. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

Original check paying for Temple Hill, signed by Heber J. Grant, January 28, 1943. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen

Surprisingly, following the announcement there was some questioning by Church members who believed the temple should be closer to downtown Oakland. They were concerned about its being situated “way up on the hill where there was no access.” Time, however, would solve the access problems. Furthermore, plans to construct a freeway through the Lake Merritt site, the other option, would make it impossible to use. [39]

W. Glenn Harmon. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

W. Glenn Harmon. Courtesy of Oakland Stake Archives; provided by Robert Larsen.

Nevertheless, shortly after the announcement, the Saints in the Bay Area held a “rejoicing meeting” on the temple site to express their appreciation for the promise of a temple. In coming months, Church members often visited the site “in contemplation of the event which [would] one day transpire there and to enjoy the beautiful view of the bay area and the nearby hills.” The Oakland hills were “studded with evergreens” and were “the [location] of many lovely homes.” The site was overlooked by the beautiful Sequoia (now Joaquin Miller) Park and was adjacent to Joaquin Miller’s “abbey,” or cottage, “where he wrote ‘Columbus’ and other well known poems.” [40]

“The temple site is almost perfect for our needs,” wrote President Hilton in 1947. “The fact that the site is on a hill will insure [sic] quiet and privacy and will always lend itself to beauty of view from the entire bay area. It is also admirably located for ease of access to the people of Northern California, and is in a locality which will never be other than choice and desirable.” [41]

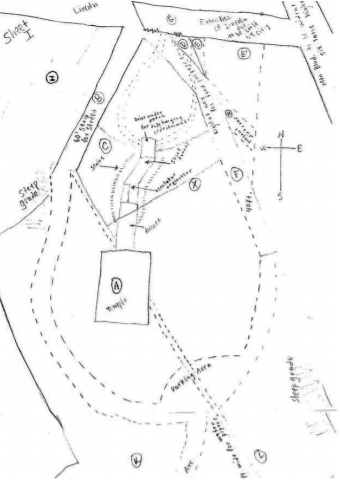

The site was evaluated for access. The approach from Coolidge Avenue to the south would be too steep. Lincoln Avenue came up the hill from the west and ended just north of the temple site. In 1947 the city of Oakland was planning to widen Mountain Boulevard, just east of Temple Hill, into a north-south highway, and then extend Lincoln Avenue to meet it. President Hilton believed that most people would come to the temple by one of these latter roads and that a two-acre parcel just north of the original purchase was “absolutely necessary to provide the proper entrance to the tract itself.” [42] Then followed the even more difficult effort to acquire this additional property.

Temple Hill before Freeways. See chapter 6 for a map of Temple Hill after the freeways were constructed. Created by Think Spatial BYU.

Temple Hill before Freeways. See chapter 6 for a map of Temple Hill after the freeways were constructed. Created by Think Spatial BYU.

For an extended period, President Hilton visited the owner, an eighty-year-old retired army colonel named Leibler, almost weekly. He and his family were not interested in selling, because this was “their country home and the place where they kept their precious horses,” and Leibler “had no interest in fulfilling a ‘Mormon prophecy.’” [43] A few years later, and after “many carefully planned and complicated efforts and delays,” the Leiblers did finally agree to sell the property for $18,000, but Church leaders in Salt Lake had authorized only $12,000. Fearing that further delay might result in losing the strategic piece and lead to the entire project’s undoing, “local stake authorities counseled together and concluded to buy the two acres on their own responsibility, knowing that time would justify their actions. They proposed to raise the extra $6,000 (nearly $60,000 today) among themselves, if necessary, rather than risk losing the natural ‘key’ to the entire project.” Thus this additional 2 acres would be purchased for almost the same amount as the original 14.5 acres. The property was finally purchased in August 1947, after which the First Presidency informed the Oakland leaders, “We have concluded that you acted wisely and will accordingly advance the entire purchase price.” [44] Significantly, this additional property is where the Interstake Center would be constructed over a decade later.

Sketch of Temple Hill by Eugene Hilton showing property needed for access. Courtesy of Church History Library

Sketch of Temple Hill by Eugene Hilton showing property needed for access. Courtesy of Church History Library

Subsequent smaller purchases brought the site’s total size to 18.3 acres. For example, W. Glenn Harmon, president of the Berkeley Stake and partner in the law firm of Johnson and Harmon, located two elderly ladies in New York who owned a piece of property on the north side of Lincoln Avenue that would connect the mission home, the temple president’s residence, Beehive Clothing, and a large parking lot to the Temple Hill site across the street. They negotiated with the two women to sell their piece of property to the Church. [45]

Eugene Hilton, who had chaired the site committee, reflected, “The hill stands apart from the noise of the city and yet is ideally located among the millions it will serve.” In later decades, a major freeway (Interstate 580) connecting the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge with California’s Central Valley would pass only about a mile below the temple. Plans for this route were not known when the property was purchased. Mountain Boulevard along the east edge of Temple Hill would eventually become Freeway 13, providing even more direct access to the temple (see the map in Chapter 6). President Hilton concluded, “The view from afar as the predicted ‘ensign’ on the hills to the east of San Francisco can never be obstructed.” [46] Church members increasingly described this site as a fulfillment of the prophecy of George Albert Smith, who by this time had become President of the Church. [47]

Even several years after the Church obtained the temple property, the local school board considered seizing it through their power of eminent domain to be the location for a proposed elementary school. O. Leslie Stone, who became the first president of the Oakland-Berkeley Stake in 1956, telephoned Stephen L. Richards—who had become First Counselor to the new Church President David O. McKay in 1951—to report this disturbing development. After a long pause, President Richards replied, “Brethren, don’t worry about it; the Lord wants that for a temple site.” Within forty-eight hours, the school board changed its plans without giving any explanation. [48] The faithful Saints regarded this as yet another evidence of “the hand of providence.” [49]

O. Leslie Stone. Courtesy of Thomas R. Stone.

O. Leslie Stone. Courtesy of Thomas R. Stone.

Stone would play a key role in the building of the Oakland Temple. Born in eastern Idaho on May 28, 1903, he came to Oakland in 1932. After filling an executive role with Safeway, he became a partner with M. B. Skaggs in a wholesale merchandise venture. Following this business career, he would become a General Authority of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1972, serving as an Assistant to the Twelve and then as a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy until his death in 1986.

Concerning what had been accomplished in Oakland, Eugene Hilton later reflected, “One of the most important and satisfying services I have ever rendered for the Church consisted in locating and recommending the purchase of ‘Temple Hill’ in east Oakland. . . . I was truly inspired and impelled to persist in this project until it was completed. I never before or since felt such strong and repeated urging by the Holy Spirit. . . . It all seemed to miraculously happen at the right time so that we could get this ‘destined’ site on which the Temple now stands!” [50] Oakland leaders anticipated that this would be regarded as the “most impressive and inspiring location” of any temple site worldwide. [51] Still, Bay Area Saints would need to wait for a decade and a half before their eagerly anticipated temple would become a reality.

Notes

[1] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, August 7, 1847, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[2] Francis M. Gibbons, George Albert Smith: Kind and Caring Christian, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 112–14.

[3] Harold W. Burton and W. Aird Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” Improvement Era, May 1964, 380; Macdonald dates this experience as the summer of 1924, but there is no evidence in George Albert Smith’s diary of a trip to California at that time. Furthermore, the annual meeting of the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America was held in St. Louis in 1924. There is, on the other hand, a record of his attending a Boy Scout meeting at the Fairmont Hotel in April 1928. A meeting between the Apostle and Macdonald would make more sense at this time, since it would have been just a few months after Elder Smith had installed him as a new stake president. Macdonald’s account was written nearly forty years after the event, and his account includes other errors in dating.

[4] W. Aird Macdonald to Spencer J. Palmer, copy in possession of Victory Nichols, Pleasant Hill, California; the letter is undated but was written in response to an inquiry dated March 14, 1951.

[5] “Report of First Stake Temple Pilgrimage,” Messenger of the San Francisco and Oakland Stakes of Zion, September 1933, 2 (title of the periodical varied throughout the years; hereafter cited as Messenger).

[6] “Pilgrimage Goes to Mesa Temple,” Messenger, January 1934, 1; see also “Temple Migration December 26,” November 1933, 1; and “Stake Pilgrimage to Arizona Temple,” Messenger, December 1933, 1.

[7] “That Extra Special Train,” an Extra of the Messenger, Winter 1935, 1.

[8] “Statement of President Johnson of Oakland Stake Presidency,” an Extra of the Messenger, Winter 1935, 1.

[9] “That Extra Special Train,” an Extra of the Messenger, Winter 1935.

[10] “Oakland Stake Second Annual Mesa Temple Pilgrimage Entertainment,” Winter 1935, flier.

[11] “Temple Excursion Highlights Recalled,” Messenger, January 1956, 2.

[12] “Highlights Recalled,” Messenger, January 1956, 2.

[13] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:469–72.

[14] “Stake Conference Draws Big Crowd,” Messenger, February 1934, 1.

[15] Burton and Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” 380.

[16] Eugene Hilton, “Temple Hill,” in David W. Cummings, Triumph: Commemorating the Opening of the East Bay Interstake Center (Oakland: Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, and Walnut Creek Stakes, 1958), 10.

[17] Evelyn Candland, An Ensign to the Nations: History of the Oakland Stake (Oakland: Oakland California Stake, 1992), 26.

[18] Arthur F. Coombs Jr., “A Sacred History of the Oakland Temple,” September 1997, 2.

[19] Eugene Hilton, as cited in Cummings, Triumph, 10.

[20] Coombs, “Sacred History of the Oakland Temple,” 3; Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10.

[21] W. Glenn Harmon, “A Dream Comes True,” in Cummings, Triumph, 11.

[22] Vinal Grant Mauss, oral history, interviewed by Matthew K. Heiss, 1989, Walnut Creek, CA, typescript, The James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[23] Mr. Patterson’s name, as well as that of his wife, Alice E. Patterson, appears on many deeds from this period of time, confirming his active involvement in real estate. See also Coombs, “Sacred History,” 3.

[24] William H. Evans, “Pilgrimage to the Temple Site,” April 1943, an undated reminiscence of Easter service, with notations by Eugene Hilton, Church History Library, MS 13944, folder 8.

[25] “Production Board Order,” New York Times, January 17, 1942; “Housing Materials Further Restricted,” New York Times, March 8, 1942; “Housing in Wartime,” New York Times, April 23, 1942; “Building Work Here Cut Sharply in 1942,” New York Times, July 18, 1942.

[26] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10.

[27] Burton and Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” 380–81; Macdonald associates this event with the Korean War, which is obviously an error because the site had been purchased years before that conflict. See also Hilton, My Second Estate: The Life of a Mormon (Oakland, CA: Hilton Family, 1968), 111.

[28] Hilton, Second Estate, 111.

[29] Oakland California City Directory 1941 (San Francisco: R. L. Polk, 1941), 388, 1116.

[30] Coombs, “Sacred History,” 3.

[31] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10.

[32] David W. Cummings, Triumph: Commemorating the Opening of the East Bay Interstake Center on Temple Hill, Oakland, January 1958 (Oakland: Oakland Area Stakes, 1959), 10.

[33] Coombs, “Sacred History,” 3.

[34] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10.

[35] Deed in Alameda County Recorder’s Office, Book 4324, 308–9. See also Burton and Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” 381; Coombs, “Sacred History,” 3.

[36] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10.

[37] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1943, 6.

[38] William H. Evans, “Pilgrimage to the Temple Site Held Sunday April 1943,” manuscript, Church History Library.

[39] Thomas R. Stone, interview by Richard Cowan, November 12, 2010, in possession of the interviewer.

[40] “Pictures of Oakland Temple Site,” Church News, March 11, 1944, 6.

[41] Hilton to First Presidency, May 3, 1947, MS 13944, folder 11, Church History Library.

[42] Hilton to First Presidency, May 3, 1947.

[43] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 10, 19; Coombs, “Sacred History,” 3–4.

[44] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 19. Coombs, “Sacred History,” states that the above authorized purchased price was $9,000. We have chosen to use Hilton’s figure of $6,000 because he was involved in the negotiations and wrote his statement forty years earlier.

[45] Beryl Harmon, in telephone conversation with the author, March 8, 2012.

[46] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 19.

[47] See, for example, Spencer J. Palmer to W. Aird Macdonald, March 14, 1951.

[48] O. Leslie Stone, “The Oakland Temple in the Making,” Improvement Era, February 1965, 109 (remarks at temple’s dedication in November 1964).

[49] Coombs, “Sacred History,” 4.

[50] Hilton, Second Estate, 111–12.

[51] Hilton, “Temple Hill,” 19.