Appendix E: Architectural Features of the Oakland Temple

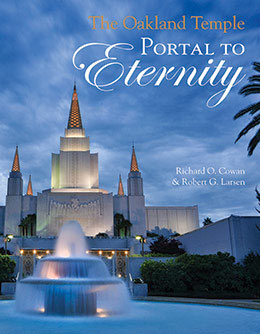

Richard O. Cowan and Robert G. Larson, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 235–245.

Harold W. Burton

Several weeks ago Bishop Manks asked me to give to the members of the Ensign 5th Ward a talk on the architectural features of the Oakland Temple. At this time I was busily engaged with the Temple’s completion, spending a great part of my time in Oakland, in order to get the Temple ready for Dedication. This Temple has now been dedicated, the Dedication having taken place on November 17th, 18th & 19th. It is therefore timely for me, as the Architect of this edifice, to describe to you the salient features of the plan and design of this building, both on the interior and on the exterior.

In describing the Temple, I hope that I will be able to give those of you that have not yet had the opportunity to view the Temple, an adequate word picture of the Temple, its setting and the approach to it.

The site is most impressive, commanding and spectacular, surely a challenge to any architect. It sets high upon the hills east of the City of Oakland. On a clear day the Temple is easily visible from almost the entire Bay area, San Francisco, Sausalito, San Rafael, and as far south as San Mateo, from the West Bay Area, from Richmond, Berkeley to the north to below San Leandro on the south from the East Bay Area. As you pass over the Bay Bridge from San Francisco to Oakland the Temple is plainly visible. After passing the Interchange on the Freeway, you travel on Highway #50 for almost two miles with the Temple setting squarely in the center of the Freeway. We can take no credit for this, as the site was chosen by President George Albert Smith in 1924 and acquired in 1938, long before the Freeway was designed and located.

From an immediate approach to the Temple site from any direction, one sees the Temple silhouetted high against the sky, with only the sky as its backing, nothing to compete with the simple outline of the Temple spires, which reflect the sun’s rays by their gold and blue coverings.

The question often asked me is “what style is the Oakland Temple?” I suppose that this is a natural question. Many people like classification. The Temple cannot be classified as belonging to any of the historical periods. Let us say that the design is contemporary or modern, with all of the clichés of this era carefully eliminated. I did not want the design classified as 1962 modern, but by its simplicity have a chance of living.

It has always been my desire to design a building without windows puncturing the facade. This was my first opportunity. Modern air conditioning apparatus and modern illuminating devices make it possible to provide a building with better air and better illumination, artificially, than by natural means.

It was my desire, prayerfully considered, to design a building unquestionably a Temple, monumental, and worthy of its sacred purpose. How well I have succeeded only time will tell.

Our Church is liberal, not requiring architects to slavishly follow any of the period styles. It allows a rather free rein in the design of its many purpose buildings.

The Oakland Temple is the fifteenth erected by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in this dispensation, fourteen of which are still standing, only the Nauvoo Temple having been destroyed.

The exterior design of the Oakland Temple is a true expression of its plan. The plan is a functional one, designed to serve the sacred purpose of the Temple. No attempt has been made to make “The Grand Plan.” Therefore, the exterior form of the Temple follows its function. The desire was to make it as simple in outline as possible, with a minimum amount of ornamentation. To some it may appear stark. Simplicity is a difficult thing to achieve. The notable architectural monuments, both ancient and modern, are simple in form, with form following function.

It has been my privilege to have been associated with the design of four of our Temples, namely, the Alberta Temple, the Hawaiian Temple, the Oakland Temple and the remodeling and additions to the Salt Lake Temple, now nearing completion.

The highlight in my career as an architect, and the most dramatic, came on New Year’s Day morning, 1912. The telephone rang. It was the Deseret News calling, trying to ascertain who the authors of the selected design were for The Canadian Temple. The First Presidency had invited eight firms of architects to submit designs for the then proposed Temple to be erected in Alberta, Canada, the first Temple to be built outside of the confines of the United States. The competitors were each given instructions regarding the size and requirement of the Temple, and were requested to make their submissions without identification marks of any kind. You will readily see the wisdom of this request. The design selected was the one submitted by my firm. I was then the junior partner in the firm of Pope & Burton.

This was surely an exciting episode to come into the lives of two young men. My wife can describe this, the highlight of our lives, much, much more dramatically than I.

My second opportunity to design a Temple came three years later, when my firm was commissioned by the First Presidency to prepare plans for and supervise the erection of, a Temple in Hawaii. This Temple, which many of you are familiar with, is a very small one. It is situated on a commanding site, set among the lush greenery of Hawaii, overlooking the blue Pacific, on the windward side of the Island of Oahu, at Laie, the first Mormon settlement in Hawaii.

The third opportunity to design a Temple came as the Supervising Church Architect and as a member of the Church Building Committee, the Oakland Temple.

The site for the Oakland Temple had been prepared prior to the erection of the Inter-Stake Center in 1955. This building is on the Temple site, immediately to the left of the approach court to the Temple. The site contains 17.5 acres, located at the head of Lincoln Avenue, near Mountain Boulevard.

The principal approach to the Temple is through a landscaped court, 105 feet wide and 600 feet long, commencing at the main entrance gates at Lincoln Avenue, extending up to the entrance to the Temple forecourt. These courts are on the main axis of the Temple 2.5° off and to the west of true north. The approach court is bounded by an evergreen hedge, and is lined with 32 palms—16 on each side of the court, paralleling a cascade of rippling water, 15 feet wide and 375 feet long. There are three arched pedestrian bridges crossing the cascade, provided with ornamental wrought metal railings. There are two companion fountains in this court, one at the entrance and one at the head of the court. Each of these fountains are set in the center of a circular basin 38 feet in diameter and bounded by a stone exedra.

Upon leaving the approach court, you come to the Temple forecourt, which is ahead of the Temple portals. The forecourt is 80 feet wide and 115 feet in depth, in the center of which is a reflecting pool 32 feet wide and 96 feet long. This pool is fed from a waterfall extending from the top of the stylobate, (the main base upon which the Temple proper sets), into a basin at the head of the reflecting pool.

Reflection pools used by ancient temple builders to enhance their sacred buildings and to increase their apparent size, have been utilized, in both the Hawaiian and Oakland Temples. These pools add to the beauty and the grandeur of these edifices.

The exterior walls of the Temple and stylobate, from the ground level up to the base of the central spire, are faced with Sierra White granite, quarried at Raymond, California, approximately 175 miles from the Temple site. This granite is one of the finest granites quarried in America. It is of even texture and color, practically free from blemishes found in most granites.

The Temple proper sets on the stylobate 210 feet from east to west, 190 feet from north to south and 21 feet high from the finished grade at the base of the stylobate up to the top of its coping. The areas between this wall and the Temple proper are beautifully landscaped with lawns, many varieties of palms, olive trees and flowering shrubs. The approach to this area is by wide granite stairways from each side of the Temple forecourt. A breathtaking panoramic view of the greater part of San Francisco Bay is afforded from this area.

The principal walls of the Temple rise 54 feet above the finished grade at the base of the stylobate walls. The central tower rises 170 feet from ground level to the tip of the spires’ finial. There are four lesser towers, each mounted with a spire reaching heavenward 96 feet. All five of the Temple’s spires are perforated, which gives them a lacelike appearance. These spires are covered with gold leaf and blue glass mosaic, and are illuminated from their interiors, transmitting rays of golden light streaming through the perforations, presenting a striking effect at night.

Exterior walls of the Temple on all faces are floodlighted at night with a golden glow. The Temple is visible at night from airplanes approaching the San Francisco International Airport, and from ships entering the Golden Gate, truly the fulfillment of President George Albert Smith’s prophetic vision in 1924 of a “White Temple of the Lord high upon the Oakland hills, an ensign to all world travellers” entering this area.

A feature of the exterior of the Temple are two sculptured panels 35 feet wide and 13 feet high, one on the north facade and one of the south facade of the building. The panel on the approach or north face of the Temple depicts Jesus of Nazareth in Palestine, scriptural references from Matthew 5:8 “Blessed are the Pure in Heart for they shall see God,” and Matthew 6:33 “Seek Ye First the Kingdom of God and His Righteousness.” The panel on the south face of the building depicts Jesus the Christ appearing to the Nephites in the Land Bountiful, scriptural reference, from 3 Nephi 11:8–10 “Behold they saw a man descending out of Heaven, and He was clothed in a white robe. Behold I am Jesus Christ whom the Prophets testified shall come into the world.” These sculptures have the appearance of being an integral part of the Temple walls, growing out of the face of the building, and not, as in many cases, appearing as being applied or “tacked on” after the building’s completion. The figures in these sculptures are heroic in size, four times life, carved from the same granite with which the Temple is faced.

The plan arrangement for the Oakland Temple was made over 11 years ago. It is quite different from the four Utah Temples, Alberta, Idaho Falls, Arizona, Los Angeles and Hawaii. It was in 1952 that Howard McKean, then the Chairman of The Church Building Committee, asked me to come to Salt Lake from my office, then in Los Angeles, to discuss with him a matter of importance. Brother McKean reported that President McKay had asked him if it were possible to plan a Temple that would be less costly to build than the current plan that was being used. It would be better to build more less expensive Temples, taking the Temple to the Saints, rather than having the Saints make long and expensive journeys to the Temple. Could I think of such a plan? Buildings, all things equal, cost by their size. It was therefore necessary to make a plan less in size, but without reducing its functional capacity if costs were to be reduced. This was a real challenge.

Shortly before this I had left the motion picture industry, where I was engaged during the World War. This industry was considered essential during the War. I was familiar with the techniques of motion picture projection. It was my opinion that if the first four Temple Ordinance Rooms could be combined, and with picture projection substituted for mural paintings to create a proper setting pertaining to the Creation, the Garden, and the World, a very substantial reduction in the size of the Temple could be effected. Proceeding with this conception, sketches were prepared and submitted. I later learned that this was thought to be too revolutionary an idea, so nothing came of it then. I later learned that the Swiss Temple was to be designed, incorporating this idea. Sometime later, the New Zealand and London Temples adopted this concept in their plans.

The Oakland Temple has two such combination ordinance rooms, with the Celestial Room serving for both, exactly the same as in the original conception. This not only reduces the plan area of the Temple very considerably, thus reducing the cost of construction. Staggering the ceremonies in these rooms effects an economy in the Temple’s operation. The same workers officiate in both rooms. It also reduces the time necessary for the ceremony, as the time required for changing from one room to the next is eliminated. The Swiss, New Zealand and London Temples have only one such combined ordinance room, which is adjacent to the Celestial Rooms in these Temples.

These two ordinance rooms in the Oakland Temple each has a seating capacity of 200. The seats are arranged in the continental fashion, having the seats spaced 3'–6" back to back instead of the usual 2'–6". You will readily see the advantage of this provision. 2400 people a day will be able to go through the ceremony in this Temple without taxing its facilities. These two ordinance rooms, owing to their size, extend through two stories. Each of these rooms is provided with a “Big Screen” 51 feet wide and 16'–6" high. The screens are curved, giving a stereopticon or third dimensional effect toward the sides of the screens.

In the exact center of the Temple, directly under the central tower and midway between the two ordinance rooms, is the Celestial Room. This room is 40 feet square and has a ceiling 35 feet in height. The eight marble encased pilasters, two on each side of this room, are the structural supports for the center tower and spire. The marble casing on these pilasters is Giallo Sienna, a beautiful golden toned marble imported from Italy. The balance of the walls in this room are lined with a light toned golden hued hardwood known as Prima Vera, which harmonizes perfectly with the marble. The floor of this room is carpeted with a deep pile velvet carpet in gold tones harmonizing with both the marble and hardwood paneling.

Directly beneath the Celestial Room is the Baptistry, which is supposed to be in the lowest portion of the Temple, according to scripture, beneath “Where the living are wont to assemble.” The floor of the Baptistry is of marble terrazzo. The sixteen supporting columns, four on each side of this room, are structural, carrying the entire weight of the center tower and spire and the weight of the Celestial Room. These columns are directly under the eight pilasters in the Celestial Room. They are cased with a travertine marble quarried in Millard County, Utah. It is of crystalline formation, with onyx and other crystals in a rich bronze-like tone. There is a marble mosaic wainscot 8 feet in height, around the entire perimeter of the Baptistry.

The Font is supported on the backs of 12 life size sculpture oxen, covered in goldleaf glazed with a transparent green glaze which gives the oxen a brass-like appearance, simulating the brass oxen described in Holy Writ of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7: 23–25; 2 Chronicles 4: 2–5; Jeremiah 52:20). The 12 oxen, three facing east, three facing south, three facing west and three facing north, are supposedly symbolic of the 12 tribes of Israel. The oxen have the appearance of emerging from reeded foliage polychromed in natural colors. These oxen are typical of those used by the early Mormon Pioneers. The Font, including the oxen upon which it rests, is an exact reproduction of the Font in the Alberta Temple, installed in this Temple in the early nineteen twenties. This Font was sculptured by Torleif Knaphus, after the design of the Architects.

There are 10 Sealing Rooms in the Temple, two of which have a seating capacity of 50 each, four seating 22 each and four seating 16 each. The walls of these rooms are paneled in silk, rare hardwoods, and with mirror panels on the sides and end walls. The mirrors give the symbolic effect of eternity, owing to the repeated reflections. The altars in these rooms are of Mexican onyx with cast bronze trim. These altars emit a warm glow of light transmitted through the translucent onyx, from electric bulbs placed inside the die of the altars.

The ground floor of the Temple is devoted to the initiatory ceremonies, the Administrative offices, including the Temple President’s office, the Temple Chapel in the east wing of the ground floor paralleling the forecourt. The west wing is devoted to the Bureau of Information and a Reception Room for Temple Patrons. There is no direct communication between the Bureau and the Temple proper. The walls of the Initiatory Rooms are covered with a satin glazed light grey tile which harmonizes with the grey Cherokee marble dressing booths and the stainless steel lockers, which will not oxidize in the salt laden atmosphere of the Bay region.

A word concerning the structural design of the Temple is in order. The entire structural elements of the Temple, including its foundations, walls, floors, roofs, columns, towers and spires, are of reinforced concrete to which the granite facings are secured with stainless steel anchors. The granite facing slabs average 70 square feet in area, and are provided with eight of these anchors around the perimeter of the slabs and with a cinch anchor in the center of each slab.

The site of the Temple is near the San Andreas earth fault. Particular care has been exercised in the Temple’s structural design, in order to withstand lateral stresses caused by seismic disturbances. Careful tests were made on the quality of the concrete, which was specified, as to the cement and aggregates, in detail. These tests were made all during the construction period by a licensed and qualified testing laboratory.

The finest materials that this world affords have gone into the building of this Temple: granite, foreign and domestic marbles, bronze, cast and extruded aluminum, rare hardwoods from all over the world, African Mahogany and Cherrywood, Asian Teak and Bengle, South American Prima Vera, American Walnut and Rift Oak: all finished in their natural colors.

The furniture throughout the principal rooms was specially designed to be in proper scale and with the architectural design of the interiors throughout. The furniture in the Celestial Room, Ordinance Rooms, Brides Rooms and the Temple President’s office, was manufactured in Salt Lake by the Granite Mill and Fixture Company, from designs and details produced by the Architect. The carpets and draperies, with few exceptions, were woven from the Architect’s design by the manufacturers of these materials. The various chairs, tables and sofas throughout, were manufactured from special designs by several Coast manufacturers and were less expensive than stock furniture of equal quality.

In closing, I would be remiss if I didn’t give credit to all who have given understanding and able assistance. To Wendall B. Mendenhall, Chairman of the Church Building Committee, who by his sympathetic assistance has given me support on many occasions during the progress of the work, and to whom I am deeply grateful. To Arthur Price, serving as Resident Architect during the construction period; to the personnel of The Church’s Architectural Department, who rendered faithful assistance during the preparation of the working drawings and specifications, to Wilford Newland, Maxwell Hess, George Nelson, Electrical, Mechanical and Structural Engineers, that assisted in the engineering designs for the Temple, to the General Contractors, Leon M. Wheatley, Inc. and Jacobsen Brothers, especially to Jack R. Wheatley and the Contractors’ foreman, Robert Loder, whose duty was the assembling of material of which the Temple was constructed and seeing that it was properly installed, and to Rudy C. Coffing, who has been most helpful in assembling of the furnishings and placing of the furniture and draperies, and supervising their production; to Marc F. Lauper, who furnished and installed the carpets throughout.

We have had fine cooperation from all who have worked on the Temple, subcontractors, artisans, craftsmen and mechanics. They seemed to feel that this building was something special, different to the regular work to which they were accustomed.

In conclusion, that which started out to be a discourse on “The Architectural Features of the Oakland Temple,” developed into relating some of the historical background and the reciting of episodes in my life which are pertinent and which finally led to the designing of this Temple. I will always cherish it as a highlight, a climax in my career as an Architect. I shall ever be grateful for this opportunity which has come to but few men in the history of this earth.

Harold W. Burton

October 18, 1964

(Harold W. Burton, “Architectural Features of the Oakland Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” manuscript MS 4235, folder 1, 1–2, Church History Library; compare Harold W. Burton and W. Aird Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” Improvement Era, May 1964, 382–86)