Announcement and Planning

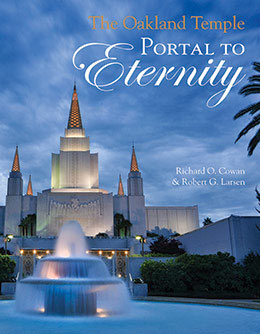

Richard O. Cowan and Robert G. Larson, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 67–86.

1955 Harold W. Burton becomes Church architect

Swiss Temple first to use films in presenting endowment

1960 Interstake Center dedicated (September 25)

1961 Plans to build temple announced (Monday, January 23)

1962 67 percent of pledged amount collected; construction begins (by May)

During the years following World War II, to maintain interest in temple activity, the Bay Area stakes continued to sponsor excursions to distant temples hundreds of miles away. Six stakes went by bus to the Mesa Arizona Temple in the mid-1950s. Bus fares at the time cost $10.00 to $12.50 per person. Other organized trips were made by car caravan. Many who went on these excursions bore testimony of the value of these trips in their lives. [1]

Many Bay Area members sensed that their temple was falling behind and that others were being constructed instead of the Oakland Temple. The Idaho Falls Temple was dedicated in 1945, Los Angeles in 1956, and three international temples—Switzerland, New Zealand, and London—by 1958. The Los Angeles Temple was particularly significant, since many thought that the Church was not ready for two temples in California and The Church began to discuss a temple in Washington, DC. Oakland became part of the Los Angeles Temple district. Oakland Stake presidents Delbert F. Wright and O. Leslie Stone both pointedly questioned Church President David O. McKay about the matter. Wright asked when the Saints in Northern California could anticipate a date for the construction of the Oakland Temple. President McKay simply replied that Oakland would likely be the next temple erected in the United States. In spite of the ambiguity of this statement, Wright seemed satisfied with the response. [2]

The Long-Awaited Announcement

On Sunday, September 25, 1960, President O. Leslie Stone of the Oakland-Berkeley Stake picked up Church President David O. McKay at the San Francisco Airport for the dedication of the East Bay Interstake Center. “I couldn’t resist asking President McKay if he could give us some indication of that day when we might expect a temple to be built,” President Stone later recalled. “I think he was ready for that question because he didn’t answer; he just smiled, chuckled a little bit, and that was all that was said at that time. I didn’t have the courage to bring it up again until after the services.” [3]

Later that evening on the way back to the airport, President Stone cautiously broached the subject of a temple once again. “President McKay, did you realize that we have 75,000 members of the Church in what would be the Oakland Temple District?” Apparently this was a new thought for the prophet: “No, President Stone, I didn’t realize that. I had thought that there was one other place we should build a temple before Oakland, but now this matter must be reconsidered.” [4] Perhaps it was this conversation that prompted Church leaders “to give priority to the building of the Oakland Temple over other temple sites which [were] under consideration.” [5]

The official decision to build the Oakland Temple came only twelve weeks later. President Stone recalled, “I shall never forget December 19, 1960, when President David O. McKay called me on the phone and said, ‘President Stone, I have just come from a meeting of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve where it was decided to proceed with construction of the Oakland Temple and I wanted you to be the first to know.’” [6] President Stone later reflected, “That was the finest Christmas I think we’ve ever had.” [7]

On Monday morning, January 23, 1961, President David O. McKay flew back to the Bay Area. At the Hilton Inn adjacent to the San Francisco Airport, he held a noon meeting with presidencies from nineteen Northern California stakes. President McKay prefaced his announcement by referring to Brigham Young’s 1847 prophecy that “in the process of time, the shores of the Pacific may yet be overlooked from the Temple of the Lord,” and to Elder George Albert Smith’s 1920s vision that a temple on the East Bay hills would be a beacon to the whole area. The President then declared, “So we feel that the time has come when these prophecies should be fulfilled.” He also acknowledged the fact that Latter-day Saints in this area had to travel a long distance to the nearest temple (in Los Angeles) to participate in this sacred work. He therefore announced that the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve had approved a temple for Oakland and that construction would begin as soon as plans could be completed. He also disclosed that Harold W. Burton, supervising architect of the Church Building Committee, had been designated architect. The Oakland Temple would be the fifteenth temple in this dispensation (including Kirtland and Nauvoo). The prophet then displayed a rendering of the proposed temple, which the architect had produced quickly and secretly in order to maintain the element of surprise in President McKay’s announcement. The description given in the Church News of this preliminary design made an obvious reference to Elder George Albert Smith’s vision: “The design calls for a powerful beacon to mount the top of the 180-foot spire of the central tower. This beacon will shoot a powerful beam of light skyward, and will be a veritable beacon to ships coming into the Golden Gate.” [8] (The concept of a single bright light on the central spire was subsequently replaced by the illumination of all five towers from within.) Of course, the assembled stake presidents “were overjoyed with these announcements.” [9]

Under President McKay’s direction, the Oakland Temple district was organized with a planning committee “for the purpose of collecting funds and working with the Church Building Committee on problems of construction.” The temple district took in nineteen stakes, a much larger area than the three stakes involved with the Interstake Center. It extended from Klamath Stake across the Oregon state line in the north; to Reno, Nevada, on the east; and to Fresno in the Central Valley on the south; it also included the Northern California Mission. President Stone became chairman of the planning committee, with David B. Haight (president of Palo Alto Stake) as vice chairman; Carroll William Smith (president of Klamath Stake) as an executive member; and Dallas A. Tueller (president of Fresno Stake) as an executive member. Paul E. Warnick of the Oakland-Berkeley high council was appointed executive secretary, and Nell Smith was called to handle publicity. Subsequently, J. Price Ronnow, president of the Reno Stake, replaced President Smith when he was called to preside over the Western Canadian Mission. Similarly, Delbert F. Wright, who was later called to be the Oakland Temple’s first president, replaced David B. Haight, who had become a mission president in Scotland.

As President McKay’s party flew back to Salt Lake City later that afternoon, he marveled, “This has been just an eight-hour day. We left Salt Lake at 10:30 this morning and are returning now at 6:25 p.m. In that eight hours we have made the round trip to the Bay area and had a scheduled three-hour meeting with the stake presidents. It hardly seems possible. It has been a remarkable day and a memorable, historic accomplishment.” [10]

Stakes in the Proposed Oakland Temple District

San Francisco

Gridley

Sacramento

Reno

Palo Alto

San Joaquin

Santa Rosa

Fresno

San Jose

Klamath

North Sacramento

Oakland-Berkeley

Hayward

Walnut Creek

San Mateo

Monterey Bay

American River

Napa

Redding

Branches of the Northern California Mission were also included

The Temple Architect

Harold W. Burton, the Church architect, received the assignment to design the new Oakland Temple. This was a fitting choice, since he had already designed the adjacent Interstake Center. Born October 23, 1887, in Salt Lake City, Utah, Burton’s interest in designing and building came early. When he was about ten years old, he was playing with the son of Bishop Harrison Sperry of the Salt Lake Fourth Ward. “They were in the old barn, and when Bishop Sperry came in to see what the youngsters were doing, he found his son and young Burton playing with sticks and with blocks. He went over to Harold and he put his hand on Harold’s head, and he said, ‘Someday you will be a builder of temples.’ Well young Burton was so impressed with that, he went home and told his mother. Many years later, his mother reminded him of that blessing.” [11] In addition to designing three temples, he would also be the architect for dozens of chapels and other church buildings. At age fifteen, Burton became an architectural apprentice in Salt Lake City. Then he became draftsman for the architectural firm of Ware and Targanza. [12]

Burton’s first experience in designing temples came during the early twentieth century. In 1910, he became the junior partner of Hyrum Pope in a new architectural firm. Pope felt that a Latter-day Saint temple should not be just a copy of a Gothic cathedral or classic temple, but “an edifice which should express in its architecture all the boldness and all the truth for which the Gospel stands” and “express all the power which we associate with God.” [13] One of their most important early projects was the temple in Cardston, Alberta, Canada. The First Presidency decided that the new generation of twentieth-century temples would depart from traditional designs in at least two important respects: they would not be adorned with towers, and they would be smaller, not having a large upper assembly room. Pope and Burton incorporated elements of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Prairie School” architecture into their “daringly modern design” for the new temple. [14] Because the temple did not include the large rectangular assembly room on the top floor, the architects were free to design the temple in a different form. The four endowment lecture rooms were placed in wings projecting outward from the celestial room, which was located in an elevated position at the center of the temple. The baptistry was located at the exact center of the temple, directly under the celestial room.

Because Church leaders were pleased with the general arrangement of the Alberta Temple, they directed Burton and Pope to prepare a slightly smaller but similar design for the Hawaii Temple. The resulting plan took the form of a Grecian cross with a flat roof at its center. Some Hawaiian members, however, were concerned that this design did not look like the Latter-day Saint temples with which they were familiar. Seeking inspiration to answer these concerns, mission president Samuel Woolley opened a book at random and found President Brigham Young’s 1853 prophecy of the time when temples would have one central tower and greenery and fishponds on the roof. Woolley was impressed that the Hawaiian temple, with provisions for flower boxes and ponds on top of the building, fulfilled President Young’s description. The architects indicated that “they knew nothing of President Young’s prophecy until several years after they had planned the Canadian and Hawaiian temples.” [15]

Recognizing the possibilities of the cement surface, the architects adorned the upper portion of the Hawaii Temple with sculptures. The resulting friezes on the temple’s four sides depicted God’s dealings with man in four great dispensations from the time of Adam to the present. [16] Thus some elements in the design of the Alberta and Hawaii Temples would also be seen in the Oakland Temple nearly a half century later.

For health reasons, in 1927 Harold Burton moved to Los Angeles, where he continued his work as an architect. Among his most important projects during this time were his two landmark stake centers in Los Angeles and Honolulu, both featuring beautiful depictions of the Savior. This feature would also be reflected in the Oakland Temple.

Then, during World War II, Burton gained unusual experience as he worked for MGM Motion Picture Studios in Hollywood. He designed and constructed sets for training films commissioned by the government as part of the war effort.

Harold W. Burton was appointed as supervising Church architect in 1955. The crowning achievement of his architectural career was his appointment to design the Oakland Temple. He would be released as Church architect in 1965, the year following the temple’s dedication. He would continue to live in Southern California, where he died four years later on September 30, 1969. [17]

Burton described the Oakland Temple’s site as “most impressive, commanding and spectacular, surely a challenge to any architect.” He noted that “on a clear day the Temple is easily visible from almost the entire Bay area.” After passing through the interchange at the Oakland end of the Bay Bridge, one travels about two miles “with the Temple setting squarely in the center of the Freeway.” But “We can take no credit for this,” Burton acknowledged, “as the site was chosen by President George Albert Smith . . . long before the Freeway was designed and located.” When approaching the temple from any direction, its elevated position means that “one sees the Temple silhouetted high against the sky, with only the sky as its backing, nothing to compete with the simple outline of the Temple spires, which reflect the sun’s rays by their gold and blue coverings.” [18]

Architect Burton reflected, “It was my desire, prayerfully considered, to design a building unquestionably a Temple, monumental, and worthy of its sacred purpose.” He further indicated that “it has always been my desire to design a building without windows puncturing the facade.” He believed that “modern air conditioning apparatus and modern illuminating devices make it possible to provide a building with better air and better illumination, artificially, than by natural means.” [19]

Burton’s architectural rendering of the Oakland Temple, first shown at the San Francisco meeting in January 1961, was refined during the next year as preparations were made to begin construction. The Church News described the temple as having a “pleasing design,” which was “modern with an Oriental flavor.” [20] The Asian architectural influences reflected and would be easily recognized by the large numbers of people from the Pacific Rim who had settled in the Bay Area.

According to Burton’s design, the upper part of the temple sits on a “stylobate,” or ground floor, measuring 210 feet east to west and 190 feet north to south. The architect explained that “the exterior form of the Temple follows its function. The desire was to make it as simple in outline as possible, with a minimum amount of ornamentation.” [21] Two wings 80 feet apart, each measuring 30 feet by 149 feet, extend north from the temple and enclose a forecourt. This area features a reflecting pool and is planted with citrus trees typical of California. Burton explained that “reflection pools were used by ancient temple builders to enhance their sacred buildings and to increase their apparent size,” and he believed that “these pools add to the beauty and the grandeur of these edifices.” [22]

The central tower rises to a height of 170 feet, while the four corner towers are 96 feet tall. “The towers are perforated and are covered in a blue glass mosaic and gold leaf,” Architect Burton explained. “They present a very striking effect in the sun light and at night will be illuminated from the interior of the spires, transmitting rays of lacy light which stream through the perforations.” [23] The architect specifically regarded this as a fulfillment of Elder George Albert Smith’s prophecy about the temple being a beacon. [24] Later, at the temple’s dedication, Elder Spencer W. Kimball would refer to Brigham Young’s 1853 prophecy that temples would have a central tower and would feature plantings and reflecting pools in their design; he would suggest that the Oakland Temple was one fulfillment of this prophecy. [25]

Because the temple is situated near the infamous San Andreas earthquake fault, the architect’s design specifically assured the temple’s strength and stability. The cement in the temple’s reinforced concrete structure needed to meet high standards. The granite facing panels, which averaged an area of seventy square feet, were attached firmly to the structure by means of eight stainless steel anchors around the perimeter and a cinch anchor at each panel’s center. Particular attention was given in the temple’s design to the need for withstanding the lateral stresses caused by earthquakes. [26]

A New Way of Presenting the Temple Endowment

In his oft-quoted book The House of the Lord, Elder James E. Talmage affirmed that “the ordinances of the endowment embody certain obligations on the part of the individual,” including a “covenant and promise to observe the law of strict virtue and chastity, to be charitable, benevolent, tolerant and pure; to devote both talent and material means to the spread of truth and the uplifting of the [human] race; to maintain devotion to the cause of truth; and to seek in every way to contribute to the great preparation that the earth may be made ready to receive her King—the Lord Jesus Christ.” [27]

Elder Talmage’s description of the endowment as a course of instruction setting forth the high standards enabling us to return to the presence of God was echoed by Elder John A. Widtsoe: “The temple endowment relates the story of man’s eternal journey, sets forth the conditions upon which progress in the eternal journey depends, requires covenants or agreements of those participating to accept and use the laws of progress, gives tests by which our willingness and fitness for righteousness may be known, and finally points out the ultimate destiny of those who love truth and live by it.” [28]

“To endow is to enrich,” taught Elder Boyd K. Packer, also of the Quorum of the Twelve, “to give to another something long lasting and of much worth.” He explained that temple ordinances endow one with divine power, with eternally significant knowledge, and with marvelous promises and challenges. [29]

In early temples, these instructions, occupying about an hour and a half, were presented in a series of rooms with murals on the walls beginning with the creation of this earth and depicting successive stages in our quest to return to God’s presence.

In 1953, when the Church’s international membership was growing at an unprecedented rate, President David O. McKay announced plans for the first “overseas temple,” which would be built in Switzerland. He indicated that “the Church could bring temples to these people by building smaller edifices for this purpose and more of them.” [30] Harold Burton recalled how in 1952, Howard McKean—then chairman of the Church Building Committee—wanted to discuss with him President McKay’s challenge to find a less costly way to build temples. This was three years before Burton became Church architect. He realized that it would be necessary to reduce the size of temples without diminishing their “functional capacity.” His experience in the motion picture industry led him to a possible solution: “It was my opinion that if the first four Temple Ordinance Rooms could be combined, and with picture projection substituted for mural paintings to create a proper setting pertaining to the Creation, the Garden [of Eden], and the World, very substantial reduction in the size of the Temple could be effected.” Although some felt this idea was “too revolutionary,” Church leaders nevertheless adopted it for the temple in Switzerland. [31]

Using this motion picture technology made it possible to present the endowment in a single ordinance room, in more than one language, and with far fewer than the usual number of temple workers. Gordon B. Hinckley, secretary of the missionary committee, had the prime responsibility of creating the film. “It was a charge of enormous significance,” his biographer declared. “The ramifications of this project were enormous, as they would extend far beyond the temple in Switzerland.” [32] In the fifth-floor room of the Salt Lake Temple where James E. Talmage had completed his monumental book Jesus the Christ, Brother Hinckley spent many evenings, Saturdays, and some Sunday mornings outlining ideas. Although other members of the committee were helpful, Hinckley soon found himself working personally with President McKay. Together they spent considerable time reviewing the temple ceremonies and praying for divine guidance. President McKay later remarked, “There is no other man in the church who has done so much in assisting to carry this new temple plan to the Saints of the world as has Brother Hinckley.” [33]

The Swiss Temple set the pattern followed for temples in New Zealand and London. Originally, each of these newer temples had only one presentation room, meaning that a new session or endowment presentation could begin only every two hours. According to Architect Burton’s design, however, the Oakland Temple would have two endowment rooms, each seating 200 patrons. This would enable a new session to begin every one and a quarter hours. Each theater had a wide screen, nearly the full width of the room, and was sixteen feet and six inches high. The screen was slightly curved, giving a “steroptican or third dimensional effect.” [34] Elder Harold B. Lee insisted that “there was no difference” between the endowment instruction given formerly “and that which was later given in temples except as to the method.” He believed that the use of films to present the “teachings of the holy endowment” had come “under inspiration to our President.” [35]

According to Burton’s design of the Oakland Temple, the celestial room is located between the two ordinance rooms, directly beneath the temple’s central spire. It is 38 feet square and has a 35-foot-high ceiling. “The walls are covered in giallo sienna,” the architect explained, “a beautiful golden-toned marble imported from Italy. The wall panels are of light-colored South American wood, known as Prima Vera [“spring” in Spanish]. This Prima Vera wood has a golden glaze which harmonizes perfectly with the beautiful Italian marble. The floor will be carpeted with a deep pile velvet carpet in a golden hue that harmonizes with the marble and wood paneling.” [36]

Directly beneath the celestial room, in the central and lowest part of the temple, is the baptistry. Its floor is marble. Sixteen columns support the weight of the celestial room and central tower above. These columns are covered with travertine marble that was quarried in Utah; their “crystalline formation with onyx and other crystals . . . gives it a rich bronze-like effect.” In the center of the room, the baptismal font rests “on the backs of twelve life-sized oxen covered with pure gold leaf.” They “have the appearance of emerging from reeded foliage, which will be polychromed in natural foliage colors. The oxen are typical of those used by the early Mormon pioneers in crossing the plains.” Fonts in Latter-day Saint temples typically follow the pattern of Solomon’s temple, where the font was on the back of twelve oxen symbolizing the tribes of Israel. The font and the oxen at Oakland are an exact replica of those in the Alberta Temple, which Burton helped to design nearly a half century earlier. [37]

Originally the temple had ten sealing rooms; two had a seating capacity of sixty, and the others were smaller. “All four walls are paneled with silk-covered panels and mirrors. These mirrors give the symbolic effect of eternity because of the repeated reflections on all sides of the rooms.” [38]

Fund-Raising

When President David O. McKay announced plans to construct the Oakland Temple in January 1961, the assembled stake presidents discussed the matter of fund-raising. “We asked President McKay that day what he thought we should raise as our local share of the cost of the temple,” President Stone remembered. “After thinking about it he said, ‘I think maybe you should raise whatever you feel is right.’ We thought perhaps that wasn’t quite definite enough, so we pressed him, ‘Could you name a figure, President McKay?’” [39] When the amount of $400,000 was suggested, they responded that “they could do a little better than that, and suggested a figure of $500,000 which seemed to please President McKay.” Under President Stone’s direction, each stake was given an allotment based on membership and distance to the temple. All willingly accepted their allotments. [40]

The experience in the San Jose Stake was unique. The stake presidency set a goal of raising the stake’s entire allotment of $32,000 in a single day. On the appointed day, priesthood members visited each home to receive the family’s cash contribution. A few weeks later, a “victory party” was held, at which the stake presented to Paul Warnick (the executive secretary and treasurer for the Oakland Temple district) a check for $32,000. San Jose was the first stake to meet its assessment, and it met its goal of doing so in a single day. Stake president Horace J. Ritchie was convinced that “it was the finest single achievement accomplished since the organization of the stake, in that it provided the spirit of cooperation, a feeling of goodness, and a real sense of accomplishment.”

In San Jose Stake’s college ward, six-year-old Kathy, daughter of institute director Paul Searle, wondered if she should contribute her share to the temple. Wisely, her father indicated that it was entirely her choice. The following Sunday she contributed to the bishop the $1.87 she had saved for a pair of new roller skates. The next morning’s mail brought her a pair of roller skates, sent by her grandparents in Utah, who knew nothing about her temple fund sacrifice. [41]

In the Hayward Third Ward, leaders acknowledged that wealthy Church members were so eager “to have a temple that they could easily pay for the whole thing.” However, emphasis was placed on having everyone participate so that they might share in the privilege and blessings of contributing to the temple fund. If everyone would donate the “per capita amount” of $5.65, the goal would be met. Even children in the Primary were encouraged to make their individual contribution. Ten-year-old Jay Pimentel took on extra chores around the house for which he was paid a dime, or a quarter “for the bigger ones.” Even though his family encouraged him to put away a comparable amount for his college fund, Jay succeeded in earning his per capita allotment. For his faithful effort, he received a certificate bearing the image of the temple and signatures of the bishopric. “It was a very memorable experience,” he later reflected. [42]

By May 1962, the original nineteen stakes in the Oakland Temple district had grown to twenty-two, absorbing all the units formerly part of the Northern California Mission. In that month, President Stone reported that 67 percent of the $500,000 pledged had been collected. In April of the following year, he reported that members in the stakes had contributed 102 percent of the amount pledged. President Stone indicated that the little Gridley Stake in the Sacramento Valley was the first to exceed their allotment. He indicated that contributions would still be accepted so that newcomers to the area and others could have “the blessings that come to those who assist in the building of the House of the Lord.” [43] President Stone anticipated that by the time of the temple’s dedication, contributions would far exceed the quota. Ultimately, over $750,000, one and a half times the pledge amount, would be raised and turned over to the Church. [44]

As funds were being collected, other preparations for building the new temple were completed. Actual construction would begin in 1962.

Notes

[1] Messenger, January 1956, 2.

[2] Delbert F. Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 1979, draft booklet, Oakland Stake Archives, 15, copy of the manuscript in possession of the authors. On Sunday, May 6, 1979, Wright met with President Spencer W. Kimball; Elder Boyd K. Packer; Arthur Haycock, private secretary to the Church President; and President Richard Sonne of the Oakland Temple. Kimball requested that an account of building the temple be prepared so that it would be available in the official record of the Church. Wright complied with this request.

[3] O. Leslie Stone, “The Oakland Temple in the Making,” Improvement Era, February 1965, 109.

[4] Stone, “Oakland Temple in the Making,” 109.

[5] Arthur F. Coombs Jr., “A Sacred History of the Oakland Temple,” September 1997, 4–5; Henry A. Smith, “As We See It . . . from the Church Editor’s Desk,” Church News, January 28, 1961, 5. A precise figure of the temple district population is not known. The population in Northern California and the northwestern states was increasing rapidly, the exact boundaries of the temple district had not been set, and mission figures were occasionally included in the count.

[6] “President Stone Tells History of Temple,” Messenger, December 1964, 1.

[7] Coombs, “Sacred History,” 5.

[8] Smith, “As We See It,” 5.

[9] Henry A. Smith, “Pres. McKay Tells of Decision to Build New Oakland Temple,” Church News, January 28, 1961, 3; Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 18.

[10] Smith, “As We See It,” 5.

[11] Romania H. Woolley (remarks, Hawaiian Temple Jubilee Celebration, November 17, 1969), copy of recording in possession of Richard Cowan.

[12] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 335.

[13] Hyrum Pope remarks, “Dedication Proceedings of the Alberta Temple, August 26–29, 1923,” 228–29, Church History Library.

[14] Paul L. Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” Ensign, July 1977, 7.

[15] “Was Brigham Young a Prophet?,” Improvement Era, November 1947, 741, 786; see also John A. Widtsoe, “The Temple in Hawaii: A Remarkable Fulfillment of Prophecy,” Improvement Era, September 1916, 955–58.

[16] J. Leo Fairbanks, “The Sculpture of the Hawaii Temple,” Juvenile Instructor, November 1921, 575–83.

[17] “H. W. Burton Dies on Coast,” Deseret News, October 4, 1969, 2B.

[18] Harold W. Burton, “Architectural Features of the Oakland Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” MS 4235, folder 1, 1–2, Church History Library. For the entire text of this article, see appendix E.

[19] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 2.

[20] “A Temple of Pleasing Design,” Church News, November 21, 1964, 12.

[21] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 2–3.

[22] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 4.

[23] Harold W. Burton and W. Aird Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” Improvement Era, May 1964, 383, 386.

[24] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 5.

[25] Spencer W. Kimball, “Accept, O Lord, Our Offering of This House,” Improvement Era, February 1965, 135.

[26] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 9.

[27] James E. Talmage, The House of the Lord (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962), 100.

[28] Widtsoe, Program of the Church (Salt Lake City: Church Department of Education, 1937), 178; Talmage, House of the Lord, 99–100.

[29] Boyd K Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 153.

[30] “Pres. M'Kay Approves Berne Temple Plans,” Church News, April 11, 1953, 7; “Temple Site Secured in Switzerland,” Church News, July 23, 1952, 2.

[31] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 6.

[32] Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 176–77.

[33] David O. McKay, Dedication Proceedings, New Zealand Temple, April 20–23, 1958, MS, Church History Library.

[34] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 7.

[35] Harold B. Lee, “Preparing to Meet the Lord,” Improvement Era, February 1965, 122.

[36] Burton and Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” 382; see also “Golden Hues Dominate Temple Interior,” Church News, November 21, 1964, 15.

[37] Burton, “Architectural Features,” 8.

[38] Burton and Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” 383.

[39] Stone, “Oakland Temple in the Making,” 109–10.

[40] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 20.

[41] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 20–21.

[42] Jay Pimentel, e-mail to Richard Cowan, May 2, 2014; Trent Toone, “‘Visible as a Beacon’: Oakland Temple Celebrates 50th Year of Service,” Deseret News, May 1, 2014.

[43] O. Leslie Stone, Memorandum 64-14 to stake presidents, August 4, 1964, copy in possession of Richard O. Cowan.

[44] “District Expected to Over-Subscribe Allotment,” Church News, May 26, 1962, 3; “22 Coast Stakes Now Over the Top on Temple Pledge,” Church News, April 27, 1963, 7; Stone, “Oakland Temple in the Making,” 110.