Salvation by Grace, Rewards of Degree by Works

The Soteriology of Doctrine and Covenants 76

Shon D. Hopkin

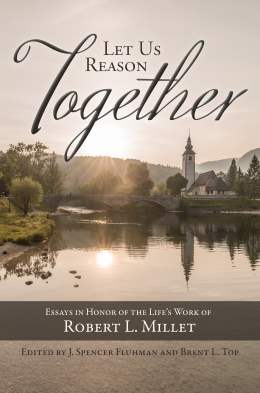

Shon D. Hopkin, “Salvation by Grace, Rewards of Degree by Works: The Soteriology of Doctrine and Covenants 76,” in Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millet, ed. J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: 2016), 329–56.

Shon D. Hopkin was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University, with research and publications focused on the Hebrew Bible, medieval Judaism, the Book of Mormon, and interfaith understanding when this was written.

In a volume dedicated to the work of Latter-day Saint scholar Robert Millet, it seems appropriate to take a closer look at Joseph Smith’s understanding of grace, faith, works, and salvation, and, moreover, to do so with sensitivity to Protestant language and concerns. As that interreligious lens is employed, a clearer view of Smith’s early soteriology, as found in key scriptural texts, emerges for both Latter-day Saints and those of other faiths, one featuring more similarities between the two traditions than some may expect but also one highlighting important and fundamental differences. I will focus primarily on a close reading of Doctrine and Covenants 76, with a brief overview of Book of Mormon passages, to argue that the soteriology of this text is one in which humankind is saved only by the grace or power of Christ through faith in him but one in which heavenly rewards are a product of works that are themselves made possible through Christ’s grace.

Many voices over the preceding two centuries have engaged the topics of grace, faith, and works for Latter-day Saints, and no study can account for the variety of approaches. Much work has already been done by Millet and others to demonstrate that the Latter-day Saint view of salvation is centered on Christ’s merits and that salvation is only possible in and through him.[1] This chapter will not attempt to address a full or complete view of Mormon soteriology, nor will it attempt to provide a full discussion of Joseph Smith’s soteriology. Rather, this close reading will show that D&C 76 provides a richly Christ-centered foundation for some of the Saints’ distinctive beliefs. The primary contributions of this paper include a demonstration that: (1) the rhetorical mechanics of D&C 76 are themselves biblical, (2) grace is the foundation in D&C 76 behind the broad distinction between saved and damned, and (3) in its broad strokes, D&C 76 not so much obliterates the classical heaven/

Grace-based Protestant Soteriology and Protestant Views of Latter-day Saint Soteriology

One of the significant concerns expressed in Protestant discussions of Mormon theology is that Latter-day Saints have a distinctly works-based soteriology. As will be seen, that concern often points most prevalently to the Latter-day Saint concept of “degrees of glory” that first found expression in D&C 76. The problem is not with the focus on Christ; both Latter-day Saints and other Christians see the work of the incarnate Son of God as the center of their faith. According to Helmut Gollwitzer, “In the center of the Christian faith, and consequently the center also of theological reflection, there stand the event of Jesus Christ and the extraordinary statements that the New Testament have made about his universal significance.”[2] Joseph Smith’s statement, frequently referred to among Latter-day Saints, reads similarly, though written one hundred and fifty years earlier, “The fundamental principles of our religion [are] the testimony of the Apostles and Prophets, concerning Jesus Christ, that He died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended up into heaven; and all other things are only appendages to these, which pertain to our religion.”[3] Rather, the difference that looms large in many interfaith discussions is the perceived role of grace, faith, and works in salvation for Latter-day Saints. Discussions of the importance of works in Protestant churches are regularly qualified by the reminder that salvation is by grace through faith in the sovereign will of God alone (rather than by works). One review of evangelical theology puts it this way: “For most contemporary evangelicals, ‘justification by grace through faith alone’ is ‘the soul of the Christian gospel.’ This is understood to be the heart of the Protestant Reformation. . . . Martin Luther’s reading of Paul’s letter to the Romans is the foundation of the doctrine of justification by faith alone, but Protestants claim Paul warrants this doctrine, not Luther. . . . The problem is that the law of God must be fulfilled, not merely externally but internally as well. The answer is that only faith in Christ fulfills it.”[4]

Those holding to this view are often suspicious of religious language that appears to unduly elevate the importance of Christian works, since that type of language may betray Paul’s teachings that “all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God; being justified freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus. . . . Where is boasting then? It is excluded. By what law? of works? Nay: but by the law of faith. Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith without the deeds of the law” (Romans 3:23–24, 27–28).[5] The danger is not only of boasting in one’s own righteousness and trusting in one’s own deeds but even more of putting man at the center of salvation rather than God. In the same passage, Paul emphasized that he was speaking in order “to declare at this time his [Jesus’] righteousness: that he [Jesus] might be just, and the justifier of him [the Christian] which believeth in Jesus” (Romans 3:26). Anglican theologian N. T. Wright describes the problem in this way: “We are not the centre of the universe. God is not circling around us. We are circling around him. It may look, from our point of view, as though ‘me and my salvation’ are the be-all and end-all of Christianity. Sadly, many people—many devout Christians!—have preached that way and lived that way. This problem is not peculiar to the churches of the Reformation. It goes back to the high Middle Ages in the western church, and infects Catholic and Protestant, liberal and conservative, high and low church alike.”[6]

Wright’s theological concerns are part of the larger dialogue of traditional Protestantism, growing in part out of perceived historical excesses and distortions in the Christian church beginning in the “high Middle Ages.” Viewing Latter-day Saint teachings through that historically developed lens reveals language that appears suspiciously works-centered to many Christians. Statements like the following by former Church President Harold B. Lee seem to some to indicate a soteriology based on works, emphasizing the righteousness of man:

Any member of the Church who is learning to live perfectly each of the laws that are in the kingdom is learning the way to become perfect. There is no member of this Church who cannot live the law, every law of the gospel perfectly. All of us can learn to talk with God in prayer. All of us can learn to live the Word of Wisdom perfectly. All of us can learn to keep the Sabbath day holy, perfectly. All of you can learn how to keep the law of fasting perfectly. We know how to keep the law of chastity perfectly. Now as we learn to keep one of these laws perfectly we ourselves are on the road to perfection.[7]

In 2013, a former Latter-day Saint expressed her own views that she had been trained by the Church to trust in her own works. Although most Latter-day Saints would likely view her message as a gross mischaracterization of their beliefs, her statements reflect some evangelical concerns with Latter-day Saint theology so closely that they were published in the evangelical magazine Christianity Today. In her description, she attacks numerous concepts, including the emphasis on obedience and on ordinances (the Latter-day Saint word for sacraments), as well as the view that salvation may include the ability to become a “god.” Each of these beliefs is discussed in D&C 76, as will be seen, although her mention of some unique practices, such as the health code known as the Word of Wisdom or the temple practice known as baptism for the dead, would not be taught by Smith until later. She wrote:

[As a Latter-day Saint] I looked down on Christians who followed the Bible. They had part of the gospel, but I had the fullness of it. I kept the laws and ordinances of Mormonism. When I took the sacrament of leavened bread and water each week at our Sunday meeting house, I was letting the sin janitor sweep away all iniquity. I believed the Mormon Church secured my eternal life. . . . Serving untold hours in church callings, reading Mormon scripture, tithing, attending meetings, keeping a health code, and doing genealogy so we could redeem the dead in the temple—these were a few of our offerings to the Mormon God. . . . Like Heavenly Father and Jesus before him—like Smith himself—Michael [my husband] was working to become a god. This is one reason we attended the temple regularly.[8]

Her statement stands in tension with consistent statements regarding the insufficiency of human works, like the following by Brigham Young, who could hardly be accused of diplomatically softening his views: “The Latter-day Saints believe . . . that Jesus is the Savior of the world; they believe that all who attain to any glory whatever, in any kingdom, will do so because Jesus has purchased it by his atonement.”[9] Notwithstanding these and similar teachings and now-decades-old work by leaders and scholars such as Millet, these works-righteousness accusations continue, as seen in the following statement from a theological journal. Notice again the inclusion of concepts first presented in D&C 76 such as entering the celestial kingdom (the concept of “degrees of glory”) and becoming gods, along with later teachings and practices like baptisms for the dead.

At least some of what Millet says has the appearance of actually misleading the reader. For instance, when he discusses that Jesus and Jesus alone “saves,” and nothing else, he fails totally in elucidating the point that, in fact, salvation or “immortality” in Mormon thought is provided for all in either the terrestrial or telestial kingdoms except for apostates from the LDS church, the devil and his angels. An evangelical might think that Millet is speaking of salvation as an evangelical does—that a Christian receives the “fullness” of salvation through, by, and because of the work of Christ alone. Not so. It is only through the “ordinances and rituals” of the “fullness” of the gospel provided by latter-day revelation and the “latter-day,” i.e., Mormon, restoration that all of salvation is possible. In other words, apart from proxy baptism once dead, only “Temple-worthy” Mormons will enter the celestial kingdom and become gods. They will be the only ones to experience the fullness of salvation. It is omissions like these that make Millet’s book [A Different Jesus? The Christ of the Latter-day Saints] so potentially misleading in the supposed rapprochement of evangelical-Mormon relations.[10]

Salvation by the Merits of Christ through Faith Alone

As seen, the Latter-day Saint notion of “degrees of glory” provides an oft-repeated basis for the accusation of works-based salvation. Salvation in the celestial kingdom is (mis)understood by non-Mormon observers (and by some Latter-day Saints, as well) as the only true salvation, a salvation that can only be “earned” by faithfully fulfilling Latter-day Saint ordinances and commandments to the best of one’s ability. According to one interpretation, this type of “real” salvation is available to Latter-day Saints through the grace of Christ, but that grace is only available to those who have “earned it” through a rigorous obedience. According to this view, a view that Wilder states she learned during her time as a Latter-day Saint, Mormons are constantly relying on their own efforts rather than on the merits of Christ, full of anxiety and depressed by their inadequacies as they try to earn a prize that will always rest just beyond their reach, and that is only accessible to perfect Mormons who have their lives fully in order. A closer look at Joseph Smith’s scriptural teachings regarding salvation in the oft-mentioned “degrees of glory” may help determine whether this viewpoint, held by some outsiders and apparently also held by some within the Latter-day Saint faith, is actually justified and whether it is a true source of distinction.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that Joseph Smith rarely used the technical language of Protestant theology to describe salvation, at least not with the nuance that might be expected from a scholar. He did not know or use the word “soteriology.” Although Smith would have understood the ordinary language of Protestantism (see, for example, the concepts of “justification through grace” and “sanctification through grace” in D&C 20:30–31), his training would not have prepared him to frame the discussion in ways that consistently relied on the theological terms of the Reformers. His teachings can nevertheless be viewed and assessed through that lens, particularly if the assessment is attuned to the differences in language and approach that could be attributed to a distinct historical context. In other words, although Mormon teachings can be viewed through a Protestant lens, those teachings should not be expected to sound exactly like they would coming from the mouth of a Protestant Christian.

Although not part of the central thrust of this article, a close reading of D&C 76, Book of Mormon descriptions of salvation provide the earliest point of reference for Joseph Smith’s soteriology. Living centuries after Jesus’ incarnation, death, resurrection, and subsequent visit to Book of Mormon peoples in the Americas, the last Book of Mormon prophet Moroni provides several statements that appear to fit well within the framework of salvation by faith in the grace of Christ, using language that often mirrors Paul’s teachings. “[Those baptized] were numbered among the people of the church of Christ. . . relying alone upon the merits of Christ, who was the author and finisher of their faith” (Moroni 6:4). He concludes the book with the call to “come unto Christ, and be perfected in him, . . . that by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ; and if by the grace of God ye are perfect in Christ, ye can in nowise deny the power of God” (Moroni 10:32). The phrase elided in the statement above emphasizes the efforts of the Christian to deny ungodliness and to love God completely, which will be discussed below, but the role of Christ as the one in whom perfection can be found corresponds well with Protestant views, as does the emphasis that an ability to acknowledge the power of God springs from his perfecting grace. Nearer the beginning of the Book of Mormon narrative, a similar statement by Nephi appears: “And we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ, and we write according to our prophecies, that our children may know to what source they may look for a remission of their sins” (2 Nephi 25:26). A few verses earlier, an oft-quoted teaching of Nephi begins in very grace-based tones but ends—depending on the interpretation—with what is to some a suspicious emphasis on human effort, “For we labor diligently to . . . persuade our children . . . to believe in Christ, and to be reconciled to God; for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23).

Notwithstanding its significant emphasis on Christ’s role in salvation, the Book of Mormon contains no overt discussion of heaven and hell in terms of “degrees of glory.” As important as it is, therefore, in understanding early Latter-day Saint understandings of faith and grace, it is D&C 76 that must be analyzed for Smith’s teachings regarding salvation and heavenly degrees of glory. These concepts are based on a heavenly vision given to Smith and Sidney Rigdon on February 16, 1832 (about twenty-two months after the organization of the Church).[11] The entire discussion is framed in the context of Christ’s mission and power. D&C 76:22–24 is memorized by Mormon youth as part of their religious training during their high school years:

And now, after the many testimonies which have been given of him, this is the testimony, last of all, which we give of him: That he lives!

For we saw him, even on the right hand of God; and we heard the voice bearing record that he is the Only Begotten of the Father—

That by him, and through him, and of him, the worlds are and were created, and the inhabitants thereof are begotten sons and daughters unto God.

The rest of D&C 76 describes salvation as starkly divided between the “sons of perdition,” for whom there “is no forgiveness in this world or in the world to come” (76:32, 34), and all others, for whom Christ was crucified, “that through him all might be saved whom the Father had put into his power” (D&C 76:42). In order to understand the biblical underpinnings of “degrees of glory” as described in D&C 76, it is crucial to first look closely at a passage that describes the division between the saved and the damned. First, describing the damned:

Thus saith the Lord concerning all those who know my power, and have been made partakers thereof, and suffered themselves through the power of the devil to be overcome, and to deny the truth and defy my power—

They are they who are the sons of perdition; . . .

For they are vessels of wrath, doomed to suffer the wrath of God, with the devil and his angels in eternity;

Concerning whom I have said there is no forgiveness in this world nor in the world to come—

Having denied the Holy Spirit after having received it, and having denied the Only Begotten Son of the Father, having crucified him unto themselves and put him to an open shame.

These are they who shall go away into the lake of fire and brimstone, with the devil and his angels—

And the only ones on whom the second death shall have any power;

Yea, verily, the only ones who shall not be redeemed in the due time of the Lord. (D&C 76:31–38)

After pausing to describe inheritors of heavenly glory, as will be discussed, the passage continues to discuss the damned, saying, “They shall go away into everlasting punishment, which is endless punishment, which is eternal punishment, to reign with the devil and his angels in eternity, where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched, which is their torment” (D&C 76:44).

The condition of the sons of perdition appears roughly equivalent with the traditional Christian view of those in hell. The language invokes King James Version phrasing to convey its message, depicting the damned as “vessels of wrath” (Romans 9:22), doomed to suffer “the wrath of God” (John 3:36; Romans 1:18; Revelation 14:10), with “the devil and his angels” (Matthew 25:41) in eternity. These are they who “shall go away into everlasting punishment” (Matthew 25:46) and be “cast into the lake of fire,” which “is the second death” (Revelation 20:14), “where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched” (Mark 9:48).

The thrust of the passage, however, bears closest resemblance to the description provided in Hebrews 6:4–6: “For it is impossible for those who were once enlightened, and have tasted of the heavenly gift, and were made partakers of the Holy Ghost, and have tasted the good word of God, and the powers of the world to come, if they shall fall away, to renew them again unto repentance; seeing they crucify to themselves the Son of God afresh, and put him to an open shame.”

On the other hand, the condition of those who are not sons of perdition sounds roughly similar to the traditional Christian view of heaven:

For all the rest shall be brought forth by the resurrection of the dead, through the triumph and the glory of the Lamb, who was slain, who was in the bosom of the Father before the worlds were made.

And this is the gospel, the glad tidings, which the voice out of the heavens bore record unto us—

That he came into the world, even Jesus, to be crucified for the world, and to bear the sins of the world, and to sanctify the world, and to cleanse it from all unrighteousness;

That through him all might be saved whom the Father had put into his power. (D&C 76:39–42)

These passages set the background context for the rest of the discussion in D&C 76 on degrees of glory. The text thus describes the unsaved and the saved before going on to describe various conditions of the saved in more detail. These details also offer a good opportunity to understand Joseph Smith’s soteriology and how his view of the difference between heaven and hell (although not using those precise terms) is presented in stark contrast. Smith, rather than being a purveyor of works-only salvation, seems in these passages to have hewn perhaps uncomfortably close to what Protestants then and now might recognize as Christian Universalism.

In the parts of D&C 76 discussed above, there is only one condition set between the unsaved and the saved. The unsaved purposefully and determinedly reject the salvation available to them through Christ, and the saved accept Christ and the salvation he offers them. This view is confirmed by one of the concluding verses of the vision, that may either describe all of the saved or may possibly refer pointedly to those saved in heaven with the lowest (telestial) degree of reward: “These all shall bow the knee, and every tongue shall confess to him who sits upon the throne forever and ever” (D&C 76:110). The message is clear: salvation is available only through Christ’s power, and belief in that power or acceptance of Christ is the only separating feature between the two sides. Put in Protestant terms, salvation is by grace through faith in God alone—rather than by works. Some may argue that Mormon teachings regarding salvation clearly require “works,” but this view—at least with regards to D&C 76—comes from conflating the view of what is required for salvation in heaven as presented in D&C 76:31–44 with the view of how rewards or degrees of glory within heaven are provided, as described in the remainder of the section and as frequently emphasized by Latter-day Saints. According to D&C 76, salvation in heaven is due solely to God’s power through Christ and the individual’s choice to accept Christ rather than purposefully deny him.

The role of free will in the Latter-day Saint view of salvation. Although the soteriology presented in D&C 76:31–44 is pointedly centered on Christ, it is not equivalent to a fully Calvinistic soteriology. As Joseph Smith provided prophetic interpretation of the Old and New Testaments in what Latter-day Saints today call the Joseph Smith Translation (JST), he consistently outlined an understanding of salvation that preserved space for mankind’s free choice.[12] The importance of the space or ability to choose what God provides for man is known in Mormon scripture as “agency” (D&C 93:31). Joseph Smith did not view God’s grace as “irresistible,”[13] because God allowed humankind the ability to accept or resist it. This view is shown in an early passage in the Doctrine and Covenants that employs the familiar Pauline terms of justification and sanctification:

And we know that justification through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is just and true;

And we know also, that sanctification through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is just and true, to all those who love and serve God with all their mights, minds, and strength.

But there is a possibility that man may fall from grace and depart from the living God;

Therefore let the church take heed and pray always, lest they fall into temptation;

Yea, and even let those who are sanctified take heed also. (D&C 20:30–34)

Joseph Smith taught the principles of justification and sanctification to the early Church, but he made a pointed, purposeful, and consistent move towards the importance of mankind’s agency that can be seen in the view of salvation presented in D&C 76:31–44. Although some Latter-day Saints have interpreted 2 Nephi 25:23 differently—conflating the state of salvation or damnation with the rewards available in heavenly degrees of glory—it is more likely through this lens of free will that the Book of Mormon passage could be read: “It is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23). If this verse is viewed in light of the soteriology of D&C 76, it could be understood as teaching that all must choose Christ in order to receive his saving power. With regards to our salvation, “all we can do” is accept Christ to the best of our ability, with all of our hearts, souls, and minds (see Matthew 22:37). An alternate view, at least as viewed through the lens of Doctrines and Covenants 76, might understand Nephi’s words as describing a heavenly salvation that enjoyed the greatest rewards available to the saved, made possible by grace and determined by a life full of good works.

Although the soteriology of Joseph Smith consistently defended the importance of free will, this view did not place man’s power at the center of salvation but rather taught clearly that free will, or “agency,” was only available through God’s power. “In the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency” (Moses 7:32). Robert L. Millet has frequently represented the Mormon view as coinciding with Wesleyan views of prevenient grace,[14] in which fallen mankind is only able to choose (or reject) Christ because God first provided the capacity to do so through his grace and power.[15] According to D&C and the Book of Mormon, Christ is both the “alpha” or the “author” of the faith of mankind and the “omega” or the “finisher” of that faith (see D&C 19:1; Moroni 6:4). In Joseph Smith’s soteriology, faith is necessary as a free-will choice, but faith appears to be possible only through God’s providing mankind with the ability to exercise it.

Rewards of Degree Based on Works

The remainder of Joseph Smith’s heavenly vision describes three degrees of heavenly glory, the “telestial,” “terrestrial,” and “celestial,” in ascending order of glory. One of the final verses of the vision explains why men are assigned to a particular degree of glory: “Every man shall receive according to his own works, his own dominion, in the mansions which are prepared” (D&C 76:111). The rewards are consistently depicted as only available due to the power of Christ, and the glory of degrees still centers on Christ rather than on humankind. Speaking of the highest, or celestial glory, D&C 76:59–61 states:

Wherefore, all things are theirs, whether life or death, or things present, or things to come, all are theirs and they are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s.

And they shall overcome all things.

Wherefore, let no man glory in man, but rather let him glory in God, who shall subdue all enemies under his feet.

Good works are viewed, even in this section of D&C 76, as possible only because of the power of God.

The reality pervading the entire section, however, is that the varying degrees of reward (available only through the power of God), are determined by one’s works. Inhabitants of the celestial glory are those who “were baptized after the manner of his burial, being buried in the water in his name, and this according to the commandment which he has given” (D&C 76:51). The terrestrial glory is occupied by “they who are honorable men of the earth, who were blinded by the craftiness of men” (D&C 76:75). Those of the telestial glory “are they who are liars, and sorcerers, and adulterers, and whoremongers, and whosoever loves and makes a lie” (D&C 76:103). Whether or not this last group can be said to belong in heaven or not, the point here is that they are assigned to a telestial glory in heaven because of their deeds that led them while on earth to be liars, adulterers, and whoremongers.

According to Hebrews 11:6, “He that cometh to God must believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of them that diligently seek him.” Although the view of degrees of reward determined by works does not coincide with a Calvinistic soteriology, it is a view of salvation that is—in certain respects—compatible with the views of some Protestant thinkers and a view that fits within the spectrum of evangelical thought concerning the “justice of God.”[16] Other differences remain to be discussed below that create a sharp divide between Latter-day Saint and Protestant understandings of heaven. The Mormon view is not the same as the Protestant view (nor does it seek to be), but a division of degrees according to works is not necessarily one of those significant divides.

Those rewards have been described by some as “degrees of glory.”[17] Evangelical writer Bruce Wilkinson, who received his theological training at Dallas Theological Seminary and Western Conservative Baptist Seminary, has written: “Although your eternal destination is based on your belief [in Jesus], how you spend eternity is based on your behavior while on earth.” “Your choices on earth have direct consequences on your life in eternity.” “There will be degrees of reward in heaven.”[18]

Among the most influential of all Christian theologians, (Augustine (354–430) taught: “But who can conceive, not to say describe, what degrees of honor and glory shall be awarded to the various degrees of merit? Yet it cannot be doubted that there shall be degrees. And in that blessed city there shall be this great blessing, that no inferior shall envy any superior, as now the archangels are not envied by the angels, because no one will wish to be what he has not received, though bound in strictest concord with him who has received; as in the body the finger does not seek to be the eye, though both members are harmoniously included in the complete structure of the body. And thus, along with this gift, greater or less, each shall receive this further gift of contentment to desire no more than he has.”[19] This should not be taken to mean, of course, that Augustine and Joseph Smith understood heaven in the same ways. Rather, this quote shows Augustine’s reasoning that some type of heavenly divisions must exist.

Similarly, Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), often recognized as America's most influential theologian, stated, “There are many mansions in God’s house because heaven is intended for various degrees of honor and blessedness. Some are designed to sit in higher places there than others; some are designed to be advanced to higher degrees of honor and glory than others are.”[20] John Wesley, the father of Methodism, used similar language: “There is an inconceivable variety in the degrees of reward in the other world. . . . In worldly things men are ambitious to get as high as they can. Christians have a far more noble ambition. The difference between the very highest and the lowest state in the world is nothing to the smallest difference between the degrees of glory.”[21]

Doing one’s best to obediently live a Christian life, while helped and strengthened by the Spirit through the grace of Christ, can also be understood as sanctification:

Sanctification of believers in the New Testament is seen primarily as the work of God, of Christ, and especially of the Holy Spirit. . . . Beyond that, sanctification is even understood as a realm of human action. Therefore, hagiasmos (the Greek term meaning holiness just as much as sanctification) can denote a state in which believers find themselves and in which they must remain by living in correspondence to their given holiness, as well as to a state to which they must strive, which they must “pursue,” or “complete” in order to attain it. Believers are thus both passive and active in their sanctification.[22]

As can be seen, although not typically seen as synonymous, living the kind of life that will be rewarded in heaven is closely connected to sanctification in some Protestant thought.

A Closer Comparison: Similarities and Differences

Can the rewards of a “telestial” glory truly be described as heaven? In the preceding discussion, I have proposed that the soteriology of D&C 76 fits in broad strokes with a Protestant soteriological view that understands salvation as available only through the grace and power of Christ, with rewards of degree in heaven possible only through the power of Christ but determined by works. The remainder of this chapter will look more closely at some of the potential or actual conflicts with the comparison.

The existence within Smith’s soteriological view of a saved group designated for the telestial kingdom (see D&C 76:81–90, 98–112) provides the greatest areas of possible difference with a traditional Protestant view. First, can the rewards of the telestial kingdom appropriately be understood as part of the biblical heaven? The following limitation of reward in that degree of glory might indicate that the answer is no when viewed in the light of a traditional Christian understanding of heaven: “[The telestial] are they who receive not of his fullness in the eternal world, but of the Holy Spirit. . . . And also the telestial receive it of the administering of angels who are appointed to minister for them, or who are appointed to be ministering spirits for them. . . . And they shall be servants of the Most High; but where God and Christ dwell they cannot come, worlds without end” (D&C 76:86, 88, 112).

If inheritors of the telestial glory cannot go where God and Christ dwell, can their salvation truly be said to describe heaven? Protestant Christians are not accustomed to thinking of a variation of rewards in these terms but might be more comfortable with the idea of certain saved beings that are allowed a closer proximity to the throne of God, using imagery provided by Revelation 4:10–11.[23] A closer proximity to the throne of God, of course, indicates that another stands further away and is not allowed into the “presence of God” to the same degree. A reward that does not allow one to stand at the throne of God imposes a similar limitation to a telestial reward that states that where God and Christ “dwell,” the saved one can never go, whether this is viewed as a world, a throne, or some other type of location. The telestial glory, existing in the heavenly realm, is in one sense very much still “in the presence” of God; it is the sons of perdition who are described as being cast into the lake of fire and brimstone with the devil and his angels. In fact, whether viewed through a Mormon lens that understands the Holy Ghost as a member of the Godhead, or a Trinitarian lens that views the Holy Ghost as one of three Persons, inhabitants of the telestial glory do dwell in the presence of God—God the Spirit—as they enjoy the presence of the Holy Ghost. Although the wording makes its interpretation inconclusive, the thrust of the quoted passage above may be that the presence of the Holy Ghost is precisely the way in which those of the telestial glory are allowed to enjoy “the fullness” of God’s influence. The first phrase states that the telestial receive not of the fullness of the Father but of the Holy Ghost. The following phrase, however, indicates that they receive “it” of ministering angels, possibly referring to God’s fullness and modifying the way the first phrase should be read.

The New Testament not only suggests a variety of rewards connected to location but can also be interpreted as suggesting higher degrees of responsibility for some in heaven (as per Luke 19:17, 19) and varying degrees of glory (and power or authority), suggested by the image of a “crown of righteousness” mentioned in 2 Timothy 4:8. D&C 76:79 actually employs the image of the crown to describe a difference in glory, authority, and power between the celestial and terrestrial glories, indicating that those who inherit a terrestrial glory had not been fully valiant in the testimony of Jesus while in mortality, and therefore “they obtain not the crown over the kingdom of our God.” The section also describes the differing glories of the celestial, terrestrial, and telestial kingdoms in terms of the light of the sun, moon, and stars (see D&C 76:78, 81), using language that Joseph Smith connected with Paul’s discourse on the resurrection of the dead (see 1 Corinthians 15:40–42).

A point of great discomfort for many Protestants when discussing Mormon soteriology, as can be seen in the quotations at the beginning of the paper, is the difference of responsibility, power, and authority known as theosis or deification that in this passage is offered as a reward of the celestial glory. Joseph Smith’s soteriological connection with theosis was first articulated in this section of the D&C (though early Latter-day Saints may not have read the passage as modern Saints do, through the lens of Smith’s later teachings): “Wherefore, as it is written, they are gods, even the sons of God—wherefore, all things are theirs, whether life or death, or things present, or things to come, all are theirs and they are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s” (D&C 76:58–59). The difference in reward described in this passage indicates that Smith’s soteriology viewed potentially deified mankind as remaining in the same relationship with Christ and the Father as “sons of God” for all eternity. According to Joseph Smith, although theosis was a reward of the highest glory of heaven, with all things being given to the celestially saved, the Christocentric relationship is maintained: “they are Christ’s.”

While the limited reward of the telestial glory might not sit comfortably with one trained to picture salvation in terms and imagery provided by traditional Christianity, a closer comparison reveals that labeling this teaching as outside the biblical spectrum may not be fully appropriate. Indeed, D&C 76:88 finishes the phrase above by restating that this should be understood as full salvation: “the telestial receive it [God’s fullness] of the administering of angels who are appointed to . . . be ministering spirits for them; for they shall be heirs of salvation” (D&C 76:88). According to Smith, he “saw, in the heavenly vision, the glory of the telestial, which surpasses all understanding. And no man knows it except him to whom God has revealed it” (D&C 76:89–90). This echoes Paul’s description of future heavenly glory: “But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him. But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God” (1 Corinthians 2:9–10).

Have those in the telestial kingdom truly accepted Christ? The Latter-day Saint inclusive view of salvation contrasted with Protestant “inclusivism.” The second challenge with understanding the telestial glory as reflecting heaven is the description in D&C 76 of the types of individuals who are saved there: “These are they who are liars, and sorcerers, and adulterers, and whoremongers, and whosoever loves and makes a lie. These are they who suffer the wrath of God on earth. These are they who suffer the vengeance of eternal fire. These are they who are cast down to hell and suffer the wrath of Almighty God” (D&C 76:103–6). This passage certainly does not describe anything a traditional Christian would expect to see in heaven. Any view of liars, adulterers, and “those thrust down to hell” as also living in a heavenly, saved condition appears to be a blatant contradiction of terms.

Upon closer reading, however, it becomes clear that the description represents decisions made on earth and prior to the resurrection and judgment. The passage goes on to state, “These are they who are cast down to hell . . . until the fullness of times, when Christ shall have subdued all enemies under his feet, and shall have perfected his work” (D&C 76:106). In other words, the destination of “hell” is not a permanent one but should instead be viewed in light of the Mormon concept of a “spirit prison,” where individuals destined for a telestial (or another) glory prepare to dwell there. Elsewhere, Joseph Smith indicated that the she’ol of the Hebrew Bible, often translated into English as “hell,” referred to the destination of the spirits of the deceased prior to their resurrection.[24] Although, as discussed above, the Doctrine and Covenants describes the future destiny of those who ultimately reject Christ (the sons of perdition) in terms similar to those used by other Christians for “hell,” Joseph Smith viewed she’ol (called “hell” in D&C 76:106) as distinct from this post-Judgment designation. Further confirmation of the difference between the condition of the figures in mortality and their state when in the telestial glory is found in their description as those who “received not the gospel, neither the testimony of Jesus” (D&C 76:101) in mortality, but in the end “all [of them] shall bow the knee, and every tongue shall confess to him who sits upon the throne forever and ever” (D&C 76:110). The Mormon view of a “spirit world” will be discussed further below.

The view that an individual could not receive the testimony of Jesus while in mortality but still end up in a saved condition might fit on the liberal end of the evangelical belief spectrum as a belief known as “inclusivism.” This view holds that Christ’s power is essential for salvation but that an epistemological awareness or active faith in Christ is not absolutely necessary to be saved. According to one of the view’s proponents,

The unevangelized are saved or lost on the basis of their commitment, or lack thereof, to the God who saves through the work of Jesus. [Inclusivists] believe that appropriation of salvific grace is mediated through general revelation and God’s providential workings in human history. Briefly, inclusivists affirm the particularity and finality of salvation only in Christ but deny that knowledge of his work is necessary for salvation. That is to say, they hold that the work of Jesus is ontologically necessary for salvation (no one would be saved without it) but not epistemologically necessary (one need not be aware of the work in to benefit from it).[25]

This view is not acceptable to Calvinists, most of whom would interpret the ignorant state of those who never learned of Christ as an evidence of their predestination to damnation according to God’s foreknowledge and sovereign will. Some other Protestants, however, find this view as rejecting the justice and mercy of God, and the inclusivist view helps them understand how a just and merciful God could deal with those who never knew of Jesus.

Christian apologist C. S. Lewis placed the inclusivist view in the mouth of the lion Aslan, who served in the Chronicles of Narnia as a metaphor for Christ. In this passage, Aslan is in conversation with Emesh, a pagan follower of the false god Tash:

Then I fell at his feet and thought, Surely this is the hour of death, for the Lion (who is worthy of all honour) will know that I have served Tash all my days and not him. . . .

But the Glorious One bent down his golden head and touched my forehead with his tongue and said, Son, thou art welcome.

But I said, Alas Lord, I am no son of thine but the servant of Tash.

He answered . . . I take to me the services which thou hast done to him. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him. Therefore if any man swear by Tash and keep his oath for the oath’s sake, it is by me that he has truly sworn, though he know it not, and it is I who reward him. And if any man do a cruelty in my name, then, though he says the name Aslan, it is Tash whom he serves and by Tash his deed is accepted. Dost thou understand, Child?

I said, Lord, though knowest how much I understand. But I said also (for the truth constrained me), Yet I have been seeking Tash all my days.

Beloved, said the Glorious One, unless thy desire had been for me thou wouldst not have sought so long and so truly. For all find what they truly seek.[26]

The Book of Mormon reflects a similar approach as that represented by Lewis, indicating that those who do good are always motivated to do so because they are serving Christ (whether or not they are aware of that reality):

A bitter fountain cannot bring forth good water; neither can a good fountain bring forth bitter water; wherefore, a man being a servant of the devil cannot follow Christ; and if he follow Christ he cannot be a servant of the devil.

Wherefore, all things which are good cometh of God. . . .

But behold, that which is of God inviteth and enticeth to do good continually; wherefore, everything which inviteth and enticeth to do good, and to love God, and to serve him, is inspired of God.

Wherefore, take heed, my beloved brethren, that ye do not judge that which is evil to be of God, or that which is good and of God to be of the devil. (Moroni 7:11–14)

Mormon goes on to explain in a uniquely Book of Mormon Christocentricity how it is possible that one who has not been taught of Christ could do good with true intent. He states that all humankind is provided with “the Spirit of Christ” (Moroni 7:16), that prompts each individual to do good and draws her or him, consciously or unconsciously, towards God. This is at least a partial explanation of Smith’s soteriological view that even those who did not know of Christ in mortality could accept him by following the Spirit of Christ.

As described in D&C 76, however, Smith’s soteriological view was both more liberal and more conservative than inclusivism. On the liberal side, it included even those who had acted in sinful ways during mortality the opportunity to suffer the wrath of God “in hell,” be cleansed, accept Christ, and be saved. The ability of the sinner to come unto Christ and be forgiven is not surprising to traditional Christians. The ability to do so after mortality but before resurrection and judgment, while in a spirit world, is more so, although the concept is not completely absent from traditional Christian thought.[27]

On the conservative side, Smith’s soteriology divides the saved from the unsaved not simply due to the power of Christ, but based on an actual, purposeful acceptance of Jesus. In D&C 76, it is not sufficient to unknowingly follow Christ. In the end, all will be given a full opportunity to accept or reject Christ. Those who accept him, exercising their faith in him, will be saved with a heavenly degree of glory. The sons of perdition purposefully reject him, turning their backs on Christ and his offer of salvation. This view is strictly Christ-centered both in terms of Christ’s power and the necessity of the choice to accept Christ’s proffered salvation. The Mormon view of a spirit world, where all who have not had the opportunity in mortality are given a full chance to learn of and accept Christ, is the soteriological teaching of Joseph Smith that allows Latter-day Saints to view God as perfectly just and perfectly merciful, just as inclusivism has fulfilled that function for some Protestants. The concept of the spirit world also helps explain the world view of Latter-day Saints, who are often prepared to appreciate the good in others (even in those who might be characterized as sinners, adulterers, or whoremongers), holding out hope that any good is evidence that the individual will someday be willing to fully accept Christ when some of the impediments of their mortal conditioning and fallen nature may be softened by death and by an interim existence in the spirit world.

Is the Latter-day Saint view of salvation broader than that found in the New Testament? If Joseph Smith’s view of salvation is indeed more similar to traditional Christian thought than has at times been understood, viewing it through that lens still reveals significant differences. First, as mentioned above, Joseph Smith’s soteriology appears to offer something much closer to a universal salvation than is typically understood in traditional Christian thought, in essence turning the view of the heaven/

Latter-day Saints, however, would interpret Jesus’ words differently, and a close analysis of D&C 76 again points toward that difference. Jesus indicated that there would be many who would find “destruction,” apōleian in the Greek, the same word used for “perdition” elsewhere in the New Testament. Apōleian can also refer to destruction or ruin, whether physical or spiritual.[29] Interestingly, Joseph Smith’s vision emphasizes that the wrath of God will be poured out upon those who will eventually be saved in the telestial world, devoting numerous verses to make that point:

These are they who suffer the wrath of God on earth.

These are they who suffer the vengeance of eternal fire.

These are they who are cast down to hell and suffer the wrath of Almighty God, until the fullness of times, when Christ shall have subdued all enemies under his feet, and shall have perfected his work. (D&C 76:104–6; see also D&C 76:84–85)

There is no way to know precisely how many inhabitants of the world will become sons of perdition using Joseph Smith’s revelatory lens, just as there is no way to know precisely how “many” will be damned using a traditional Christian lens. The similarity of the described quantity in Jesus’ words and the account regarding the telestial world, however, is striking.

A statement from a later revelation to Joseph Smith provides another hint regarding a Latter-day Saint interpretation of Jesus’ words. Speaking of a celestial salvation in the highest degree of glory, D&C 132:24 states, “This is eternal lives—to know the only wise and true God, and Jesus Christ, whom he hath sent.” Put together, these two verses seem to indicate that Latter-day Saints would view the large quantity headed to “destruction” as describing those who will experience God’s wrath before being saved with a telestial glory, and that Jesus’ statements about “eternal life” would be interpreted (at least in this later revelation) as referring to the rewards available in the celestial degree of salvation, referred to as “eternal lives.” Once again, D&C 76 relies on biblical wording and biblical framing but in this case uses that wording in ways that do not match how those verses have been read in Christian thought over the centuries.

Why do Latter-day Saints talk about works so much? If it is correct to say, as proposed in this article, that Joseph Smith’s soteriology in D&C 76 provides salvation or damnation based only on an acceptance or complete rejection of Christ’s role and power, and that the degrees of glory are offered in consequence of grace-enabled works, each degree of glory representing true salvation, then this understanding highlights another significant shift in focus between Protestant and Latter-day Saint discussions of salvation. Joseph Smith’s highly inclusive view of salvation maintains Christ’s role at the center and encourages or requires Latter-day Saints to exercise faith in him, but appears to represent a situation in which many or most will attain salvation, while the Protestant view consistently and fervently encourages Christians to rely solely on Christ because their salvation is highly at risk. The Mormon view—relying in part on the soteriology of D&C 76—instead focuses on encouraging a desire for all to obtain the highest degree of glory possible and constantly invites Latter-day Saints to give their all to the best of their ability in that pursuit.

The Latter-day Saint understanding of degrees of glory continues to emphasize that these rewards are only possible because of Christ, as in Brigham Young’s statement above, and that only as the individual exercises faith in Christ will she or he receive the strength to obey in more and more appropriate ways—referred to as sanctification by both Latter-day Saints and Protestants. In other words, even the Mormon view of degrees of glory awarded according to one’s works is centered on Christ’s power, and Latter-day Saints do not expect to truly “earn” their degree of glory in heaven. Rather as they choose to give themselves completely to Christ, Christ will soften their weaknesses and provide an opportunity for a celestial salvation. However, the distinction does highlight a different focus that would lead Latter-day Saints to do all they can to choose a godly life through the power of the Spirit. This focus on Christ-enabled good works, then, should not be understood as simply a product of the Mormon pioneer heritage, but rather as a function of their unique theology—a unique theology and soteriology that, again, has not been fully described in this reading of D&C 76. Although it is somewhat an oversimplification of all the issues at hand, it could be said that Latter-day Saint discourse tends to focus more on sanctification, whereas Protestant discourse may focus more on justification. Understanding this varying focus would be helpful for both outside observers and Latter-day Saints themselves.

The extensive treatment of degrees of reward in heaven in D&C 76 also means that Latter-day Saints have much more to say about what many of those distinctions will be. It could be said that the Protestant focus provides a broad view of salvation as a whole, while the Mormon focus highlights the great varieties of heavenly situations that will be encountered in the next life in order to encourage themselves and others to seek after the highest rewards available through the grace of Christ. This focus means that most Latter-day Saints would not anticipate a feeling of perfect contentment in a telestial degree of salvation (in distinction to Augustine’s statement). Rather, they long for the blessings available only in the celestial glory of salvation.

Viewing the soteriology of D&C 76 through a Protestant lens highlights the fact that this text does not provide a works-based salvation. Rather it teaches that true salvation is available through the grace of Christ based solely on God’s power and our choice to accept the salvation he freely offers to all. Joseph Smith’s teachings about the degrees of glory should be understood as heavenly rewards based on works, with Christ still standing at the center. Notwithstanding the similarities that comparing these viewpoints reveals, it also highlights significant differences in biblical interpretation, approach, and focus. The goal of this study is not to explain away those differences, but rather to help the reader understand (1) that Latter-day Saints have more in common with other Christians than both traditional Christians and Latter-day Saint Christians might initially believe, and (2) that viewing Mormon theology through a traditional lens provides a clearer picture of what the differences actually are and why they exist. In the case of this discussion, those points can help Protestants understand why Mormon prophet Harold B. Lee and others would feel comfortable making some of the strongly works-oriented statements quoted above, and why Brigham Young could claim that Latter-day Saints “believe that all who attain to any glory whatever, in any kingdom, will do so because Jesus has purchased it by his Atonement.”

As a devoted Latter-day Saint, I find beauty in Protestant understandings of salvation centered on Christ but find great joy in the equally (I believe) Christ-centered soteriology of Joseph Smith. To my mind, that soteriology reveals the compassion, love, wisdom, and justice of God, and provides a nuanced view of God’s plan for humankind and of the great variety of human interaction I experience in my life. As a Latter-day Saint, I have been taught to believe that I can merit nothing without Christ and that both my salvation and my subsequent situation in heaven would be impossible without his substitutionary atoning sacrifice. I need Christ every step of the way to lift me from my weaknesses and provide the strength and hope necessary to continue onward. I also believe that God expects me to freely choose to give my whole self in pursuit of a godly life and to completely turn myself over to him to the best of my ability if I desire to gain the “prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:14), with all of its attendant blessings.

Notes

[1] See, for example, Robert L. Millet, By Grace Are We Saved (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989); Bruce C. Hafen, “Grace,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:560–62.

[2] Helmut Gollwitzer, An Introduction to Protestant Theology, trans. David Cairns (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1982), 62.

[3] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930), 3:30.

[4] D. Stephen Long, “Justification and Atonement,” in The Cambridge Companion to Evangelical Theology, ed. Timothy Larsen and Daniel J. Treier (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 79–80.

[5] All biblical quotes are from the King James Version as found in the official scriptures of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, published in 2013.

[6] N. T. Wright, Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision (Great Britain: Ashford Colour Press, 2009), 7.

[7] Teachings of Harold B. Lee (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2014), 331.

[8] Lynn Wilder, “Mormon No More,” Christianity Today, December 2013, 80.

[9] Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997), 30.

[10] R. Philip Roberts, “The SBJT Forum: Speaking the Truth in Love,” Southern Baptist Theological Journal 9 (2005): 74.

[11] See Matthew C. Godfrey, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833, vol. 2 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 179–92.

[12] See, for example, JST, Exodus 7:3 and Exodus 9:12 in the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible.

[13] See P. Toon, “Hyper-Calvinism,” in New Dictionary of Theology (Downer’s Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 324.

[14] See R. Kearsely, “Grace,” in New Dictionary of Theology, 280.

[15] Robert L. Millet and Gerald McDermott, Claiming Christ: A Mormon Evangelical Debate (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2007), 185. See also Brian Birch’s discussion of agency, grace, faith, and works in Latter-day Saint thought in “Are Mormons Pelagians? Autonomy, Grace, and Freedom,” in 2010 Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology (Utah Valley University, March 25, 2010).

[16] See H. G. Anderson, et al., eds., Justification by Faith (Minneapolis: Lutherans and Catholics in Dialogue VII, 1985); see also P. F. Jensen, “Merit,” in New Theological Dictionary, 422.

[17] My thanks to Robert Millet for directing me to the quotations found in this and the subsequent two paragraphs.

[18] Bruce Wilkinson, A Life God Rewards (Colorado Springs, CO: WaterBrook Multnomah Publishers, 2002), 23, 25, 98.

[19] St. Augustine, The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods (New York: Random House, 1978), 865.

[20] Edwards, as cited in Wilkinson, A Life God Rewards, 119.

[21] Wesley, as cited in Wilkinson, A Life God Rewards, 120–21.

[22] K. Bockmuehl, “Sanctification,” in New Dictionary of Theology, 613–14.

[23] This is certainly not a common interpretation in Christian thought, but the possibility does exist. See, for example, the discussion of Christ’s throne in James D. G. Dunn, The Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon: a Commentary on the Greek Text, in The New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), 204.

[24] The Words of Joseph Smith, ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1980), 211–12.

[25] John Sanders, No Other Name: An Investigation into the Destiny of the Unevangelized (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1992), 215. My thanks to Bryan Ready of Peoria, Illinois, who pointed me to this quotation, and who freely and knowledgably discussed many of the concepts mentioned in this paper from a Reformed perspective.

[26] C. S. Lewis, The Last Battle, in The Chronicles of Narnia (New York: HarperCollins, 1956, 1982), 756–57.

[27] For a review of Jewish and Christian thinking on a world of departed spirits that acts as a temporary abode between life and death, see David L. Paulsen et al., “The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies and Other Restoration Scripture 19, no. 1 (2010): 56–77; and David L. Paulsen and Brock M. Mason, “Baptism for the Dead in Early Christianity,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies and Other Restoration Scripture 19, no. 2 (2010): 22–49.

[28] R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew in New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 287.

[29] Oepke, “ἀπόλλυμι, ἀπώλεια, πολλύων,” Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. G. Hittel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964), 1:396.