Nurturing Father

Mark D. Ogletree, “Nurturing Father,” in No Other Success: The Parenting Practices of David O. McKay, ed. Douglas D. Alder (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 47-60.

“You are not going to bring back erring youth unless you first let them know that you are interested in them. Let them feel your heart touch. Only the warm heart can kindle warmth in another. . . . The kind hand or the loving arm removes suspicion and awakens confidence.”

—David O. McKay[1]

To be a nurturing father is to be a father who cares about his children, who is involved in their lives, and who encourages their development and growth. Nurturing fathers must have a positive, healthy relationship with each of their children. Without such a relationship, fathers will have little influence on their children.[2]

Elder Robert D. Hales stated, “In many ways earthly parents represent their Heavenly Father in the process of nurturing, loving, caring [for], and teaching children. Children naturally look to their parents to learn of the characteristics of their Heavenly Father. After they come to love, respect, and have confidence in their earthly parents, they often unknowingly develop the same feelings towards their Heavenly Father.”[3] It was Brigham Young who encouraged fathers to treat their families “as an angel would treat them.”[4]

As fathers strive to be Christlike, they will hopefully desire to treat their children in a manner that the Savior would treat them. Nurturing fathers should not only demonstrate care and concern for their children but also should attempt to recognize the needs of their children and then attempt to meet those needs. Strong fathers should provide for their children what they need at the time they most need it.[5] Nurturing fathers continually strive to be actively involved in their children’s lives. Simply put, these men are involved with their kids. Such men are not afraid to show affection towards their children. David O. McKay was this kind of father. He demonstrated care and concern as he waited upon his children and showed them affection. And, for a busy man, he was involved in their lives.

Tuned In

President David O. McKay taught, “Parents cannot with impunity shirk the responsibility to protect childhood and youth.”[6] Even though David was gone much of the time, his family was constantly on his mind. For example, on Wednesday, 31 July 1907, he wrote in his diary from Denver: “I am worried as I write this because I feel that all is not well at home. . . . Sent a telegram to Ray inquiring about the children.”[7] It seemed that throughout his travels, the Spirit prompted him to know when his children were sick or otherwise afflicted.

Much of David O. McKay’s care, concern, and desire to protect are evident in the letters he wrote to his family while he was away on Church business. For example, shortly after his call to the Quorum of the Twelve, he wrote Emma Ray from Cedar City, Utah:

Had a pleasant rest last night, and feel well this morning. I dreamed, however, that Lawrence nearly got run over by an automobile. The little hero kept his head and schemed to escape. It seemed so real, I feel a little worried. Don’t stay alone nights. Get Annie and Tom to occupy the little room. I wish I could give you a Birthday kiss, but I must keep it and give it with interest when we meet. Kiss baby and Lawrence. Accept my truest love, and believe me.

Your own, Dade[8]

From this letter, it is easy to detect that Emma Ray and the children occupied his mind constantly. Here he was, on a stake conference assignment, worried about Lawrence and dreaming of a potential accident. This dream prompted David to ask Emma Ray not to stay alone at night.

Sickness, Loss, and Grief

One of the challenges that both David and Emma Ray had to contend with was dealing with sick children. Like other parents in the early 1900s, the McKays had children that were stricken with coughs, colds, pneumonia, measles, flu, and a host of other illnesses. It was difficult for Emma Ray to shoulder the load of tending to her sick children while balancing her many other responsibilities. At the same time, it broke David’s heart to leave his worn-out wife and sick children behind as he traveled the world as an Apostle. The most acute anxiety he faced was worrying for his wife and sick children. For example, on Friday, 2 August 1907, he was relieved because he had just returned from a stake conference assignment, and the children were sick. He wrote in his diary that when he arrived home, the baby “was very sick, she had been for two weeks. Lawrence was better; Llewelyn, ailing. . . . Spent a happy day with Ray and our babies.”[9]

On Tuesday, 13 August, David reported that he arrived home at 6:45 a.m. to find their baby still very sick: “Lawrence with a severe cold in addition to his cough, and Ray quite worn out.”[10] During the month of October 1907, sickness continued in the McKay home. David recorded that on Friday, 25 October 1907, his little daughter had contracted pneumonia, “and today we are anxious about her condition. Her fever is high . . . spent a night of anxiety.”[11] On Sunday, 27 October 1907, David wrote that his daughter was still sick but that her health was improving. However, he stayed home for the entire next week helping Emma Ray and the babies.[12]

Perhaps one of the most tender and sacred experiences for David as a father occurred when their young son, Royle, became very sick. Initially, the baby seemed to have pain in his knee, accompanied by fever and lethargy. Royle was diagnosed with rheumatism. Meanwhile, it was the April general conference, and David had church responsibilities to tend to. He wrote in his diary: “Learning by telephone that baby is worse, I returned home at 11:45 p.m. Poor little Royle! He is suffering from an infected knee, probably caused by a fall. The doctors do not know what is the matter; but Dr. Morrell thinks the infection has been in his system since his recent illness. Baby seems a little better, but his fever is still around 104.”[13]

David must have gone back to the conference the next morning. He wrote in his diary that he was present at the Salt Lake Tabernacle at 10:00 a.m. Immediately after the morning session of the conference, the following occurred: “At noon, I learned by telegram that Royle will probably have to be taken to the hospital. [I] feel that I ought to miss the afternoon meeting and go home to my wife and baby boy, but finally concluded to remain until 4:00 p.m. . . . Up all night with our sick boy. Fever has been 106.”[14]

The following day, 7 April 1912, David wrote that at 3:30 a.m., Royle had two seizures within a two-hour time period. He further recorded:

The Doctors have concluded that his only hope is in having an operation, and this is extremely hazardous because of the congenital weakness in his heart.

The operation was performed under the direction of three doctors . . . Dr. Morrell supervising. Everything was successful. The diagnosis had been just right. At 10:35 a.m. all was over, and we felt encouraged.

He soon recovered from the effects of the anesthetic, and was less feverish and entirely conscious all day, but towards the night his breathing became short, and his fever began to rise.

He was evidently in great pain from some other cause besides his little afflicted leg. O what a night of suffering for our darling boy! Every breath he drew seemed agony to him!

The doctors examined him this morning and discovered that his pain was due to Pleurisy on both sides. At this, we almost lost hope, but later when Dr. Morrell told us that by an examination he knew what germ had caused the infection, and that he had the anti-toxin, we again took courage.

But Royle was too weak, and complications of diseases too many. He battled bravely all day, taking the little stimulant given him at intervals as willingly as a grown person would. About 9:30 p.m. Papa, Thomas E., and I again administered to him. Ray felt very hopeful, and lay down…. beside him for a little rest.

Soon his little pulse weakened, and we knew that our baby would soon leave us. “Mama” was the last word on his . . . lips. Just before the end came, he stretched out his little hands, and as I stooped to caress him, he encircled my neck, and gave me the last of many of the most loving caresses ever a father received from a darling child. It seemed he realized he was going, and wanted to say, “Good-bye papa,” but his little voice was already stilled by weakness and pain…. . . . Death had taken our baby boy.

The end came at 1:50 a.m. without even a twitch of a muscle. “He is not dead but sleepeth” was never more applicable to any soul, for he truly went to sleep—He did not die.[15]

To read this account is heart-wrenching. The days following Royle’s passing were somber in the McKay home. It took the family more than a short while to get their “legs under them again.” In the years that followed, Royle was often on the mind of David and Emma Ray. Each Memorial Day that followed his death, the family stopped by the Ogden Cemetery to pay tribute to Royle.[16]

Dealing with Homesickness

David O. McKay with Tongan Kids. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

David O. McKay with Tongan Kids. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

One of the most difficult journeys for David was the world tour of 1920–21. With traveling companion Hugh J. Cannon, David went from one end of the earth to the other. There were times of danger, and of course there were many spiritual experiences. The most difficult aspect of the entire experience for David was being away from his family for such an extended period of time. On this voyage, David’s letters to Emma Ray and the children were rich and deep.

For example, he wrote:

I’m really homesick this morning. This monotonous life in the month of June is beginning to tell on my nerves. Last night and this morning I’ve thought almost continuously about the folks at home. . . . I can even now see the kiddies playing on the lawn, Mama and Lou Jean on the summer porch, and Llewelyn on his way to the Dry Hollow farm. June 11th I imagined him coming home with feet soaked and trousers wet to the hips, but happy because he caught four fish. . . . If I were home, I should be in a better place, but Travelers must be content.[17]

On 5 May 1921, after being away from home a short five months (relative to the entire trip), he wrote his daughter Lou Jean, while aboard the SS Tofua:

My darling Lou Jean:

If you knew with what tenderness I have written “My darling Lou Jean,” this morning, you would have an absolute assurance that whatever else may come to you in life, you have a father who loves you dearly.

If this world tour does nothing else, it will imprint upon my soul everlastingly how dearly I love your sweet mother and you children! I’ve often said to mama that I did not believe that “absence makes the heart grow fonder,” nor do I this morning. If that were true the world would die of grief for loved ones gone. I do believe, however, that a little absence does increase one’s fondness.[18]

While on the same ship, David received a telegram from Emma Ray, indicating that all was well at home, and that she missed him very much. David wrote back, “As this was the first line from home since I left March 26th,[19] you don’t blame me for shedding a tear or two. Everybody well, and hearts still warm! What else matters? Health and Love are after all the greatest blessings of life. With these as our assets, we shall one day be out of debt; and, in the meantime by happy as cooing doves.”[20]

Father Kind and Dear

David O. McKay taught in general conference, “Homes are made permanent through love. Oh, then, let love abound. If you feel that you have not the love of those little boys and girls, study to get it. Though you neglect some of the cattle, though you fail to produce good crops, even, study to hold your children’s love.”[21]

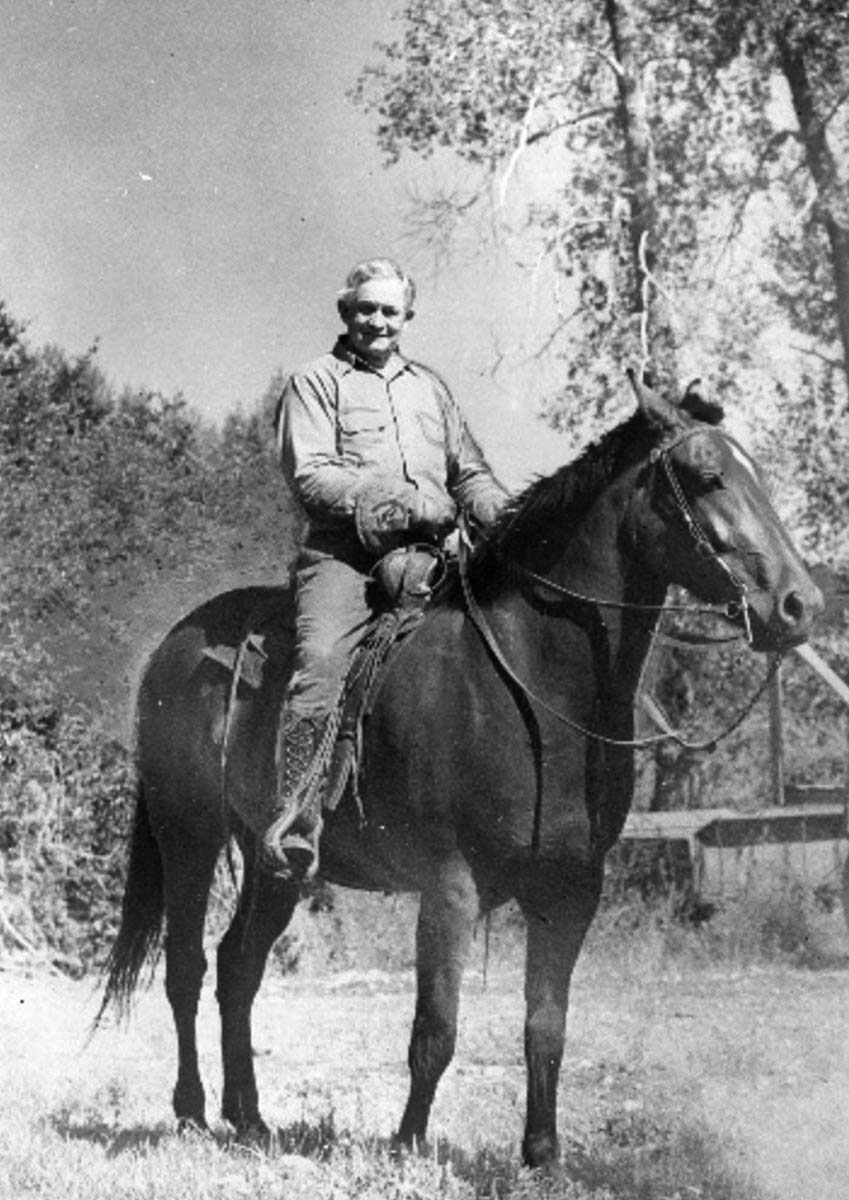

David O. McKay enjoyed riding.

David O. McKay enjoyed riding.

David deeply loved his children and expressed that love through his words and deeds. For example, he brought Lawrence with him on a Church trip to Kanab, Utah. While there, the weather took an extreme turn for the worse, and flash floods encompassed the area. David wrote to Emma the next day, “My anxiety for Lawrence was worse than the dreariness of the night. But we were blessed and protected. We passed through perilous places that day, and escaped without one serious mishap.”[22] It is easy to detect David’s deep feelings and concern for his son. It must have been a harrowing experience for him to even mention it.

Years later, Lawrence provided more details of this experience. He related that as soon as they got off the train in Marysvale, they were met by the stake president, Joseph Houston, and the weather was treacherous. They traveled the fifty miles to Panguitch in a buggy, getting drenched in the deluge. The next day, they traveled another thirty miles in their buggy to Cannonville to set apart a new bishop. David reported, “I remember watching the red mud coming up and falling off the wheels all day.” Eventually, the party came to a river that they decided to cross. The water was up to the horses’ bellies. They drove for a while along the side of the mountains, but there were big rocks coming down. They turned back, but by now, the river had risen, and the water was moving swiftly. They had no way to cross, and they were trapped.

Lawrence said, “I thought it was the end of the world and I started to cry. Father took me in his arms and held me all night, keeping me dry. Finally, I went to sleep. In the morning, the flood had subsided and two men came on horseback across what was left of it and guided us to Cannonville.”[23]

Lawrence concluded from that experience, “It’s hard to disobey a man who loves you and puts his arms around you.”[24] The love between father and son here is obvious. Here is a good example of a father, willing to sacrifice his own needs for the care and comfort of his son, and of a son, who loves and admires his father because he understands what his father has done for him.

Just before David Lawrence departed for his mission to Switzerland, he and his father spent the day working the farm in Huntsville. Lawrence stopped to gaze at the farm for one last long look. His father said to him, “You’re feeling it already, the loneliness.” Not long after Lawrence arrived in France, David wrote to him, “Now that you are gone, Huntsville hasn’t much attraction for either of us[25] [David and son Llewelyn].”[26]

Long-Distance Education

Because David was gone so often, letters were not simply a way to connect with his children and express his love and concern. Letters also became the medium through which David was an involved father and taught his children crucial principles that weighed on his mind. The following letter is an example of this long-distance teaching. The letter was written in May of 1909 from St. Johns, Arizona. Observe how David teaches Lawrence both academic and spiritual principles in the letter. At this time, Lawrence would have been eight years old:

My dear Lawrence:

When I came to St. Johns last Thursday, I found a sweet—loving letter from your mama waiting for me, and one from you, written so carefully and punctuated so correctly that I took pleasure in showing it to President Hart and others. I am so glad that you received all A’s on your report card. I hope you will always get A’s in everything you do, and especially in obeying Mama.

When we were coming into St. Johns, we saw a horned toad. Have you ever seen the picture of one?

Ask mama to show you a map of the United States, and then see if you can find St. Johns.

They haven’t had any rain here for several months, and they don’t expect any until July 15th. Everything is dry, except in the towns where a little water comes from the creeks. The people haul their water in barrels, and water tanks. They are building reservoirs to hold all the water. When they get these built, they will have plenty of water, and then this will be good country.

I am sending you and Llewelyn a nickel each. Please give Lou Jean and Mama a share of what you buy with the money, and tell Lou Jean that papa has bought for her something very pretty. I bought it from an Indian.

There are many Indians and Mexicans in Arizona. . . .

Kiss Mama, Lou Jean, and Morgan, and Grandpa for me, and don’t forget Josephine too.

With love to my boy, and best wishes for him always, I am

Your affectionate father

David O. McKay[27]

Years later, yet with the same sensitivity, David O. McKay apparently approached the subject of a girlfriend Lawrence must have had while serving as a missionary. He wrote his son the following letter:

One reference in your letter emphasizes the fact that you are just at a very impressionable age. I mention the fact simply to remind you that a young man’s affections are very much like a young colt that is just being trained—He’s alright as long as the trainer has a firm hold on the lines, and can keep him in the road. He wobbles around a good deal, but as long as he keeps going straight ahead, there’s no need for worry. More than one pretty girl will make your heart go pit-a-pat; but keep your mind’s eye on your missionary road.

You have some sweet brothers and sisters, and an ideal Mama, and they are all proud of their missionary brother and son. Such a family, I think makes life worth living. The success of parenthood may be rightly measured by the nobility of its sons and daughters! . . .

Please let us know about how much money you will need each month. A good way to ascertain this is to keep an accurate account of your daily expenditures. This is as good a training as keeping a diary.[28]

David O. McKay’s letters to his children reveal that he was the consummate teacher. He often found ways to breach sensitive topics with his children, but his approach was with love, concern, and kindness. In the previous letter, we see his versatile ability to address topics from male-female relationships to basic accounting. From being away for so long, David learned to teach and influence his children through letters.

Father to All

A good measure of a father’s spiritual progress is his care and concern for those around him. A successful father is not merely concerned with his own children, but he is concerned for the well-being of all children. President David O. McKay’s son Edward shared the following experience to illustrate this point. He related that President McKay’s car had been stolen.

The police apprehended the thief, and it turned out to be a young boy of about twelve or thirteen. President McKay was asked if he wanted to prosecute the boy. He replied, “No, I will take care of it.” He then interviewed the boy and asked him why he had stolen the car. The boy answered that he just wanted to try to drive a car. President McKay told him to come over to his house, and he would let him drive his car. He did that once a week for a long time. The young boy later became a police officer so that he could help others as David O. McKay had helped him.[29]

David O. McKay’s care and concern blessed the lives of many children, not just his own. Because of the tender way he handled situations in and outside of his family, lives were changed and improved. For instance, instead of this young boy growing up to continually break the law, he chose to enforce it as his career. Moreover, when fathers care about their offspring, that love is most often reciprocated.[30] David O. McKay is an example to modern fathers on how to demonstrate care and concern. Another prophet, Joseph F. Smith, taught fathers how to demonstrate Christlike love to their children. He said:

If you wish your children to be taught in the principles of the gospel, if you wish them to love the truth and understand it, if you wish them to be obedient to and united with you, love them! And prove to them that you do love them by your every word or act to them. . . . When you speak or talk to them, do it not in anger, do it not harshly, in a condemning spirit. Speak to them kindly; get them down and weep with them if necessary and get them to shed tears with you if possible. Soften their hearts; get them to feel tenderly toward you. Use no lash and no violence . . . approach them with reason . . . with persuasion and love unfeigned. With these means, if you cannot gain your boys and your girls . . . there will be no means left in the world by which you can win them to yourselves. But, get them to love the gospel as you love it, to love one another as you love them; to love their parents as the parents love the children. You can’t do it any other way. You can’t do it by unkindness; you cannot do it by driving; our children are like we are; we couldn’t be driven; we can’t be driven now. . . . You can’t force your boys, nor your girls into heaven. You may force them to hell, by using harsh means in the efforts to make them good, when you yourselves are not as good as you should be. . . .You can only correct your children by love, in kindness, by love unfeigned, by persuasion, and reason.[31]

David O. McKay believed these doctrines as taught by Joseph F. Smith. He modeled his life after these teachings, as his children have now passed them on to the next generation. This was a man who connected with his children by doing this with them; he demonstrated his love both verbally and physically and left no doubt in his children’s minds that he loved them. When he corrected or disciplined his children, love ultimately prevailed. He taught his children the gospel of Jesus Christ by word and deed, and perhaps most importantly, he did all of these things with a loving and loyal wife at his side. Emma Ray helped David to temper his passions and to value relationships more than anything else.

Notes

[1] David O. McKay, Gospel Ideals, 404.

[2] President Ezra Taft Benson taught, “I am convinced that before a child can be influenced for good by his or her parents, there must be a demonstration of respect and love.” Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, April 1981, 46.

[3] Robert D. Hales, “How Will Our Children Remember Us?” Ensign, November 1993, 8–9.

[4] Brigham Young, Discourses of Brigham Young, comp. John A. Widtsoe (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954) 197–98.

[5] David C. Dollahite, Alan J. Hawkins, and Sean E. Brotherson, “Narrative Accounts, Generative Fathering, and Family Life Education,” Marriage and Family Review 24, nos. 3–4 (1996): 349–68.

[6] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1935, 112–13.

[7] Diaries of David O. McKay, April 1906 to June 1907, MS 668, box 4, folder 2, Marriott Library, 35.

[8] David O. McKay to Emma Ray Riggs, 23 June 1906, David O. McKay Family Papers, 1897–1954, MS 21606, box 1, folder 1, CHL.

[9] Diaries of David O. McKay, April 1906 to June 1907, MS 668, box 4, folder 2, Marriott Library, 36.

[10] Ibid., 43.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Diaries of David O. McKay, February to December 1912, MS 668, box 5, folder 2, Marriott Library.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] David recorded in his diary on 30 May 1932 that “Mama Ray, Ned, Bobby, and I visited the S.L. Cemetery, and placed flowers on Grandma Riggs and others graves. . . . We stopped at Royle’s grave in the Ogden Cemetery, then continued on to Huntsville.” This was twenty years after Royle’s death. See Diaries of David O. McKay, January to November 1932, MS 668, box 7, folder 11, Marriott Library.

[17] Llewelyn McKay, Home Memories of President David O. McKay, 75.

[18] David O. McKay to Lou Jean McKay, 5 May 1921, David O. McKay Papers, MS 668, box 1, folder 5, Marriott Library.

[19] He had been gone since early December of 1920.

[20] David O. McKay to Emma Ray McKay, 4 July 1921, David O. McKay Papers, MS 668, box 1, folder 5, Marriott Library; underline and capitalization in original.

[21] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, October 1917, 58.

[22] David O. McKay to Emma Ray Riggs, 4 September 1909, David O. McKay Family Papers, 1897–1954, MS 21606, box 1, folder 1, CHL.

[23] David Lawrence McKay, interview by Gordon Irving, James Moyle Oral History Program, Salt Lake City, January–May 1984, 22–23.

[24] John Stewart, Remembering the McKays, 30.

[25] It appears that once Lawrence arrived into the mission field, his family didn’t hear from him for some time. One can speculate which of his parents would have been more worried. The letter reads: “My Dear Son, David L: We have been wondering, almost every waking minute since you left, how you fared as a traveler. . . . Emma Ray was the first in the family to write you a letter. You will find it enclosed herewith. The love she expresses comes from her dear little heart; and that is love, my dear boy, that we all have for you. We are proud of your manliness, and grateful for your high ideals and keen sense of honor. Our confidence in you is absolute, and we feel sure that you will do your best to prove worthy of the Priesthood and to magnify every Calling you may receive as a true servant of the Lord. May Heaven’s choicest blessings be yours during your entire mission!” McKay, My Father, David O. McKay, 109–10.

[26] David O. McKay to David L. McKay, 29 October 1920, David O. McKay Papers, MS 668, box 2, folder 1, Marriott Library.

[27] David O. McKay to David L. McKay, 22 May 1909, David O. McKay Family Papers, 1897–1954, MS 21606, box 1, folder 1, CHL.

[28] David O. McKay to David L. McKay, 29 October 1920, David O. McKay Papers, MS 668, box 2, folder 1, Marriott Library.

[29] Edward McKay, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, 30 June 1995.

[30] David was in a serious car accident in Ogden Canyon while serving as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Someone had fastened a rope across the highway so drivers would not drive across the bridge because the river was so dangerous. David could not see the rope until it was too late. The rope smashed the car window and caught David under the chin, severing his lip, lacerating his face, knocking out his teeth, and breaking his jaw. On Sunday, Emma Ray gathered Lawrence, Llewelyn, and Lou Jean together to close their fast for their father and eat some breakfast before church. Llewelyn, who was ten at the time would have nothing to do with eating. Instead, he ran to the hospital to see his father. Before entering, he picked some bluebell and buttercup flowers for him. He then asked the nurse if he could see his father. The nurse then showed Llewelyn into the hospital room, where he placed the flowers in David’s hand. Both the nurse and Llewelyn were crying. See Lou Jean McKay Blood, interview with Mary Jane Woodger, 8 August 1995.

[31] Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1939), 316–17.