Introduction: A Fathering Crisis

Mark D. Ogletree, “Introduction: A Fathering Crisis,” in No Other Success: The Parenting Practices of David O. McKay, ed. Douglas D. Alder (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), ix-xvi.

“No other success can compensate for failure in the home.”[1]

—J. E. McCullough

There is a fathering crisis in our nation, and American families must wake up and face reality. The fatherhood debacle that emerged in the 1990s has not disappeared as many have supposed. If anything, the problem has continued to gain momentum. In a 2006 survey, 91 percent of the respondents strongly or somewhat agree that there is a crisis of father absence in our country.[2] In May of 2011, in a front-page story featured in the Deseret News entitled “Fatherless America?,” Elizabeth Stuart reported that one-third of American children are growing up without their biological father in the home. According to the US Census Bureau, during the past fifty years, the percentage of children who live with two married parents has dropped twenty-two points. Meanwhile, the number of babies born to unwed mothers has jumped from 5 percent to 40 percent.[3]

Father absence is such a pressing social issue that every United States President since Bill Clinton has addressed the consequences of a fatherless society. Former President George W. Bush declared:

Over the past four decades, fatherlessness has emerged as one of our greatest social problems. We know that children who grow up with absent fathers can suffer lasting damage. They are more likely to end up in poverty or drop out of school, become addicted to drugs, have a child out of wedlock or end up in prison. Fatherlessness is not the only cause of these things, but our nation must recognize it as an important factor.[4]

According to a Gallup poll, seven in ten adults believe that a child needs both a mother and a father in the home to be happy.[5] However, there is often a significant gap between the ideal and the real. For example, in America, 24.35 million children (33.5 percent) live absent of their biological father,[6] and of students in grades 1–12, 39 percent live in fatherless homes.[7]

Father Irrelevance

Nonetheless, every child in America is not without a father. The good news is that most men in America live with their children; therefore, father absence is not a problem that the majority of American families contend with. Perhaps a more universal problem is father irrelevance. Too many fathers in our society are not necessarily absent from their homes, but they are certainly uninvolved in the lives of their children. These men are often disconnected emotionally, socially, and certainly spiritually.[8] Perhaps much of this trend is driven by the economic conditions of contemporary families. Fathers seem to be working longer hours to supply their children with material possessions and to pay down their own debts. Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Robert Coles further explained:

Parents are too busy spending their most precious capital—their time and their energy—struggling to keep up with MasterCard payments. . . . They work long hours to barely keep up, and when they get home at the end of the day they’re tired. And their kids are left with a Nintendo or a pair of Nikes or some other piece of [junk]. Big deal.[9]

In a Gallup opinion poll, 96 percent of the respondents said that their families were either extremely important or very important.[10] Once again, most of us seem to understand what matters most in life. There is a disconnect between how we live and the way we believe. Even though many American fathers value their family and make sacrifices for their children, it appears that too many are unwilling to spend time with their children on a regular basis. Unfortunately, many American fathers are spinning their wheels as they seek to bless their children with material possessions. First of all, most children do not express gratitude for their father’s hard work or for what he is providing. Second, deep down, most children would rather have time with their dad than a new trinket of some sort.

Moreover, the time famine causes fathers to feel guilty for not being home as much as they should. By the time a father answers to a boss, work demands, or the bill collector, there is very little time left for his children. Too many fathers today feel that purchasing material goods for their children is the primary method of showing love.[11] For them, materialism compensates for involvement.

The Time Famine

Today, 70 percent of fathers and mothers feel that they do not have enough time to spend with their children.[12] Consider that a child in a two-parent family will spend, on average, 1.2 hours each weekday and 3.3 hours on a weekend day directly interacting with his or her father. Overall, the average total time fathers are accessible to their children is 2.5 hours on weekdays and 6.3 hours on weekend days.[13] Economist Juliet Schor has argued that over the past two decades the average worker had added 164 hours—a month of work—to their work year.[14]

Despite all of this, most fathers would like to be home more often and spend more time with their children. A MasterCard survey found that almost 85 percent of fathers claimed that “the most priceless gift of all” was time spent with family.[15] Furthermore, 62 percent of fathers reported that they would be willing to sacrifice job opportunities and higher pay for more family time.[16] Contrary to popular belief, most men want to be good fathers.[17] In fact, the majority of men enter marriage dreaming about positive family relationships with their future children. For example, in one study, family researchers discovered that 74 percent of men would rather have a “daddy-track” job than a “fast-track” job.[18] Happiness does indeed come from family life, and most men understand that.[19] In one study, men who engaged with their families more than their work experienced a higher quality of life compared to those who spent most of their time focused on work.[20]

Families do matter, and most American fathers are committed to their families.[21] It is somewhat paradoxical, however, that although most fathers consider family life valuable and worthwhile, oftentimes their laptops receive more “hands-on” time than their children. Unfortunately, many contemporary fathers have found it too easy to neglect their families.

Not only do families matter, but research repeatedly documents that fathers also matter. In his landmark book Life without Father, author David Popenoe concluded, “I know of few other bodies of evidence whose weight leans so much in one direction as does the evidence about family structure: On the whole, two parents—a father and mother—are better for the child than one parent.”[22] Other experts have documented that a father’s involvement in a child’s life influences three key outcomes: economic security, educational attainment, and the avoidance of delinquency.[23] From a gospel perspective, Latter-day Saints understand that a loving, caring, involved father can affect his children physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually as well. The influence of a strong father in the lives of his children is unmeasurable.

Where Have the Heroes Gone?

Unfortunately, there is certainly a dearth of fatherhood role models in our country. Not long ago, men did not have to look very far for paternal examples. Role models could be found in the home, community, and media. It could be argued that since April of 1992, when The Cosby Show went off the air, television has not provided a nurturing father role model.

Since then, father bashing has been in season. Fathers have been depicted in media circles, special interest groups, and on prime-time television as unfit and inadequate at best. The most predominant way of thinking about fathering is that it is a social role which men usually perform awkwardly. For example, contemporary prime-time television portrays these “doofus dads” as troubled, deranged, pudgy, generally incompetent, and not terribly bright.[24]

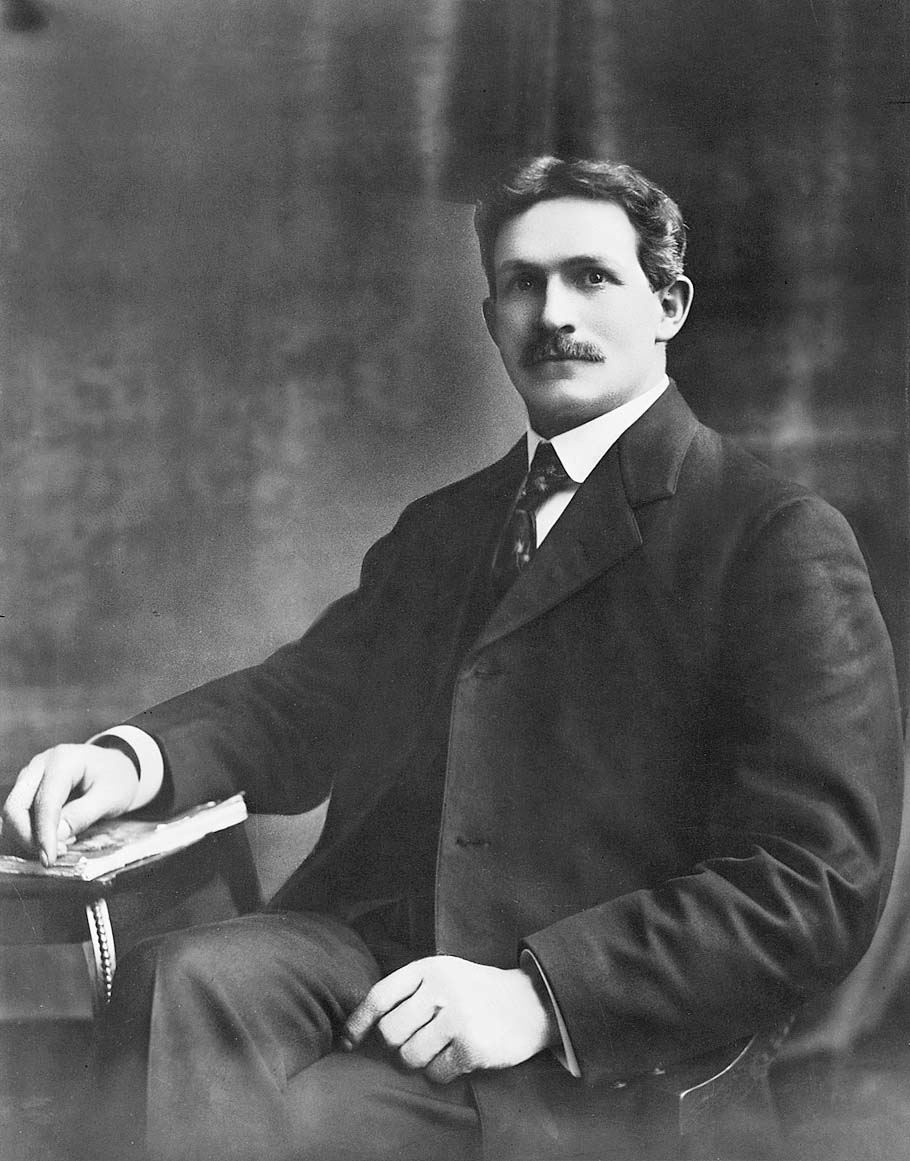

David O. McKay was in his early thirties when he was called to be an Apostle and hence had a young family to tend to. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

David O. McKay was in his early thirties when he was called to be an Apostle and hence had a young family to tend to. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

Where can men look for fatherhood role models? With such a shortage of fatherhood examples, men have fewer and fewer places to turn. In the Father Attitudes Survey, 74 percent of the respondents looked at other fathers or men as examples and resources to improve their fathering. Ironically, only 62 percent looked at their own fathers as examples.[25] President Spencer W. Kimball helped Latter-day Saint fathers know where to look for paternal examples. Besides their own fathers and perhaps other close relations, President Kimball explained, “We all need heroes to honor and admire; we need people after whom we can pattern our lives. For us Christ is the chiefest of these. . . . Christ is our pattern, our guide, our prototype, and our friend. We seek to be like him so that we can always be with him. In a lesser degree the apostles and prophets who have lived as Christ lived also become examples for us.”[26]

One such hero or role model was the man, father, and prophet—David Oman McKay. He was married to Emma Ray Riggs, and they had seven children. President McKay spoke more on marriage and family life than perhaps any other Church leader of his era. He believed actively and deeply in the family, and he lived his life in accordance with what he taught. During the 1950s and ’60s, most members of the Church looked to President and Sister McKay as role models for happiness in family living. Even today, President McKay still stands as a healthy example of fatherhood. If men want to be successful fathers, they might well study the life of President McKay.

Like contemporary fathers today who work long hours and travel extensively with their jobs, David O. McKay was busier than most men of his generation. How was David O. McKay able to balance his Church life and his professional career with his family? Unlike most men who are called into the Quorum of the Twelve in the twilight of their lives, David O. McKay had young children in the home during his service in the Quorum of the Twelve and the First Presidency. As an author and researcher, I have had the privilege of reading David O. McKay’s diaries and personal letters housed in the Special Collections at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library. I have discovered that he was a remarkable father, despite the fact that he traveled so extensively when his children were younger, and that so much Church responsibility was placed on his shoulders at a relatively young age. This book will attempt to demonstrate how David O. McKay connected with his children, nurtured them, loved them, and disciplined them.

We will first examine a brief history of fatherhood so that we can view David O. McKay in the proper context. It is never fair or appropriate to try to place historical figures into contemporary settings. To understand how David O. McKay operated as a father, we must look at him in the proper early twentieth-century context. For example, it was very unusual in the early 1900s for fathers to be in the delivery room when their wives gave birth to children. Today, contemporary husbands are helping deliver babies and cutting umbilical cords—a foreign practice to fathers in the McKay era. After a historical view of fatherhood, we will consider the following father strengths that David O. McKay possessed: commitment, creativity, ability to nurture and build relationships, flexibility, and discipline. Strong and effective fathers perform well in these areas, and we will demonstrate how successful David O. McKay was in each of these realms.

Notes

[1] J. E. McCullough, Home: The Savior of Civilization, (1924), 42.

[2] Norval Glenn and David Popenoe, Pop’s Culture: A National Survey of Dad’s Attitudes on Fathering (National Fatherhood Initiative, 2006), 7.

[3] Elizabeth Stuart, “Fatherless America?,” Deseret News, 22 May 2011, A1.

[4] George W. Bush, in Father Facts, 5th ed. (National Fatherhood Initiative, 2007), 20.

[5] George Gallup, “Report on the Status of Fatherhood in the United States,” Emerging Trends 20 (September 1998), 3–5.

[6] See table 1 in R. M. Krieder and J. Fields, “Living Arrangements of Children, 2001,” Household Economic Studies, July 2005, 70–104.

[7] See table 1 in C. W. Nord and J. West, Father’s and Mother’s Involvement in their Children’s Schools by Family Type and Resident Status (Washington, DC: US Department of Education; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2001).

[8] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland declared, “Of even greater concern than the physical absenteeism of some fathers is the spiritually or emotionally absent father. These are fatherly sins of omission that are probably more destructive than sins of commission.” Jeffrey R. Holland, in Conference Report, April 1999, 17.

[9] Robert T. Coles, Father Facts, 5th ed. (National Fatherhood Initiative, 2007), 114.

[10] D. W. Moore, “Family, Health Most Important Aspects of Life,” 3 January 2003, http://

[11] In one study, half of the parents surveyed equated buying things for their children to caring for them. In the same study, 35 percent of parents thought that fathers who act like their careers are more important than their families are very common, while only 22 percent of parents believe that fathers who are loving and affectionate toward their children are very common. See S. Farkas et al., Kids These Days: What Americans Really Think about the Next Generation (Public Agenda, 1997).

[12] J. T. Bond et al., The 1997 National Study of the Changing Workforce (New York: Families and Work Institute, 1998).

[13] W. J. Yeung et al., “Children’s Time with Fathers in Intact Families,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 63 (February 2000): 136–54.

[14] In the 1980s alone, vacations were shortened by 14 percent. Economist Victor Fuchs has claimed that between 1960 and 1986, “parental time available to children per week fell ten hours in white households and twelve hours in black households.” See Arlie Russell Hochschild, The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work (New York: Henry Holt Company, 1997), 6.

[15] J. Harper, “Americans Celebrate Dad Today in All of His Different Disguises,” Washington Times, 18 June 2000, C1.

[16] Darryl Haralson and Suzy Parker, “Dads Want More Time with Family,” USA Today, 15 June 2005, D1.

[17] John Snarey, How Fathers Care for the Next Generation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[18] Another research project documented that 48 percent of fathers have reduced their working hours so that they could spend more time at home, and 23 percent of the men surveyed had declined promotions so they could spend more time with their families. Such statistics reflect that most men value family life and want to be successful at it.

[19] According to Pop’s Culture: A National Survey of Dad’s Attitudes on Fathering, 76 percent of the respondents felt that they are better fathers than their own fathers were to them.

[20] J. H. Greenhaus, Karen M. Collins, and Jason D. Shaw, “The Relation Between Work-Family Balance and Quality of Life,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 63 (December 2003): 510–31.

[21] J. D. Schvaneveldt and Margaret H. Young, “Strengthening Families: New Horizons in Family Life Education,” Family Relations 41 (October 1992): 385–89.

[22] David Popenoe, Life without Father: Compelling Evidence That Fatherhood and Marriage Are Indispensable for the Good of Children and Society [Insert from p. 22 n. 2] (New York: Free Press, 1996), 8.

[23] K. M. Harris, F. F. Furstenberg Jr., and J. K. Marmer, “Paternal Involvement with Adolescents in Intact Families: The Influence of Fathers over the Life Course,” Demography 35 (May 1998): 201–16.

[24] J. Warren, “Media and the State of Fatherhood,” in Father Facts, 11.

[25] Glenn and Popenoe, Pop’s Culture, 24.

[26] Spencer W. Kimball, “Preparing for Service in the Church,” Ensign, May 1979, 47.