David O. McKay in Historical Context

Mark D. Ogletree, “David O. McKay in Historical Context,” in No Other Success: The Parenting Practices of David O. McKay, ed. Douglas D. Alder (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 1-10.

“The father who, because of business or political

or social responsibilities, fails to share with his wife the

responsibilities of rearing his sons and daughters is

untrue to his marital obligation, is a negative element

in what might and should be a joyous home atmosphere,

and is a possible contributor to discord and delinquency.

David O. McKay”[1]

A brief examination of the history of fatherhood in America will provide better understanding and the context for David O. McKay as a father. In discussing the evolution of fatherhood, there appears to be three instrumental time periods worth examining: the colonial and puritanical period, the enlightened and industrialized period, and the “breadwinnerhood” versus fatherhood period. Incidentally, in reviewing these three periods, it becomes apparent that fatherhood has always been primarily driven by the nation’s economic situation, which will be shown hereafter.

The 1700s: Colonial and Puritan Fatherhood

During the 1700s, the role of the American father was distinct. He was the head of the household, the unquestioned ruler: stern, rigid, and authoritative.[2] Moreover, he was the preeminent teacher of religion, morals, and values in the home. In fact, “a man who neglected the educational and religious life of his children disqualified himself as a good father. Nor could a good father leave the discipline of children to his less trusted, more pliant and emotional wife.”[3] It appeared that the father ruled the roost while his wife assisted him as was needed or requested. Interestingly, during this time period, parenting books were directed toward the father because he was considered the primary parent—not the mother. Not only were men the chief educators in their homes, but they were also the prime public educators as well. The entire school system was taught and administered by men.

Furthermore, since the Puritan father was agrarian, he was a “stay-home” dad—making a living on the farm. The colonial father was a man who essentially worked from home. As such, this father spent a great deal of time with his children—interacting with them by reading, studying, working, and playing. Consequently, his influence was directly felt by his children as most of his day was spent in their presence.

The colonial father deeply valued his children and home life. Even so, colonial fathers were not characterized as having open or affectionate affiliations with their offspring.[4] In fact, the parent-child relationship of this period can certainly be characterized as a working one—the child worked next to his or her father most of the day.[5] The father was the stern boss, and his children were essentially his employees. Regarding parenting, the father was the key player while his wife served as his assistant.

The 1800s: Enlightened and Industrialized Father

The 1800s yielded a different father. Indeed, a metamorphosis occurred as fathers were encouraged to change their temperament from stern and harsh to more tenderhearted and empathetic. This time period also became known as the age of industrialization and urbanization. As families began to migrate from the country to the cities, the fathers’ prime responsibility was altered dramatically. Family scholar David Popenoe further explained: “As income-producing work left the home, so—during the weekday—did the men. Men increasingly withdrew from direct-care parenting and specialized in the provider or breadwinner role. The man’s prime responsibility was to take care of his families economic needs. . . . For the first time in history on a large scale, women filled the roles of mother and housewife full-time.”[6]

However, men were still viewed as the head of the home, but they were now becoming assistants to their wives instead of the other way around.[7] The roles of men and women were changing during this period of enlightenment and industrialization. Perhaps some of these changes were constructive and beneficial. After all, it seemed that men and women were becoming more complete as their assets and liabilities flowed together into a joint marriage account. Men were taking upon them some feminine qualities, and women were assuming a more masculine posture in the home. After all things were considered, this shift seemed like a good idea.

However, the experts contended that such changes were not healthy for the society. For example, Stephen M. Frank argued, “As some fathers began to spend more time at work and less time at home, and as family structure shifted away from patriarchal dominance and toward more companionate relationships, paternal requirements shrank.”[8] Simply put, relationships at home were certainly more affable, but the role of father was diminishing.[9] In fact, 1842 was the year a New England pastor warned that paternal neglect was causing “the ruin of many families.”[10] So, as men began to gradually slip out of their children’s lives, parenting books and child-rearing manuals began to focus on mothers; after all, they were the ones who were now raising the children.

However, not all fathers at this juncture were deadbeats. There were some men, perhaps many, who were enjoying their fathering role during this time in our nation’s history. These fathers were making time for their children. Toys, books, games, children’s names, and even home structure reflected a newfound love for children and parenting.[11] Other evidence suggests that fathers enjoyed playing with their children, “lamented separation from them, frequently gave them gifts, worried about their health, celebrated their accomplishments, and looked after their academic preparation.”[12]

The 1900s: Breadwinners Versus Fathers

By the turn of the twentieth century, the role of the father changed again. A good father was now defined as one who helped his wife. Masculinity was redefined, and male toughness became a major theme. Traits such as competitiveness, assertiveness, and “virility” became desirable. Popenoe reported: “This shift in the definition of masculinity—away from family protector-provider towards expressive individualism—was damaging to fatherhood. A locker-room mentality among young males was growing. Male excitement and adventure were emphasized, and masculine humor grew disparaging of marriage and family responsibility. Children were increasingly left out of the male equation. More men were leaving their families.”[13]

Thus, men took a step from patriarchy to individualism. Most men were too arrogant to become “second fiddle” in domestic duties. Therefore, many fathers dropped out of the home-life picture altogether. Although David O. McKay lived during this time period, he appears to be the exception rather than the rule when it comes to involved fathers. Yes, President McKay was busy, but he was an involved father. Not only was he nurturing, but he made time for his children. He had a strong personal connection with each of his children; consequently, he had a strong influence in the lives of each of his children.

For example, in the April general conference of 1967, President McKay’s son Robert spoke in the priesthood meeting. During the late ’60s, President McKay had become too ill to speak in general conference; therefore, his sons would most often read his prepared messages to the general Church membership. However, this message was somewhat different because Robert actually shared a brief message before delivering his father’s remarks. He said:

Brethren, I think there isn’t a son among you here who would pass this opportunity in the presence of about 95,000 brethren to tell your father how much you loved him. The question comes to me frequently, as it does to my brothers, “How does it feel to be the son of a prophet?” How do you answer a question like that? You don’t explain it; you live it.

As my father, he has my love and devotion, and I echo the thoughts of my brothers and sisters. As the President of the Church, and as a prophet of our Heavenly Father, he has my obedience as a member of the priesthood, and my sustaining vote.

I can say this, and act as a personal witness, because in all of my years of close association in the home, on the farm, in business, in the Church, there has never been shown to me one action nor one word, even while training a self-willed horse, which would throw any doubt in my mind that he should be and finally did become the representative and prophet of our Heavenly Father. I leave you that personal witness, and I will close that in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.[14]

It is not hard to detect in this message Robert’s love, respect, and adoration for his father. The fact that he never witnessed his father act in any way that was not in harmony with the behavior of a prophet of God is a powerful statement. Because of David O. McKay’s great love for his children, he was able to have a strong impact on their lives. As an aged prophet, he reaped the dividends that came from an investment he made years earlier—spending time with his children.

1900 to the 1930s

This time period marks perfectly the fatherhood period of David O. McKay. Each of his seven children was born between 1900 and 1930. During this time, the role of the American father had become clear-cut: the man’s primary duty was to be the family breadwinner. Instead of being defined in terms of moral teaching and patriarchy, successful fathers became men who could “bring home the bacon.”[15] Consequently, the family lost its stability, structure, popularity, and power. The national birthrate dropped from 7 children per family in 1800 to 3.56 in 1900.[16]

America was in trouble, and many fingers began pointing toward fathers. An article appeared in the 7 July 1932 issue of Parents Magazine entitled “For Fathers Only,” which seemed to identify to the core of the crisis. The article labeled contemporary teenagers as “the generation of woman-raised youth” and concluded with this statement: “Perhaps the answer to the frequent question, ‘What’s wrong with modern youth?’ is simply, ‘It is fatherless.’”[17] The article might have been premature, but the point was well made: if fathers did not reassume their role and become more involved with their families, the nation would be in deep and serious trouble.

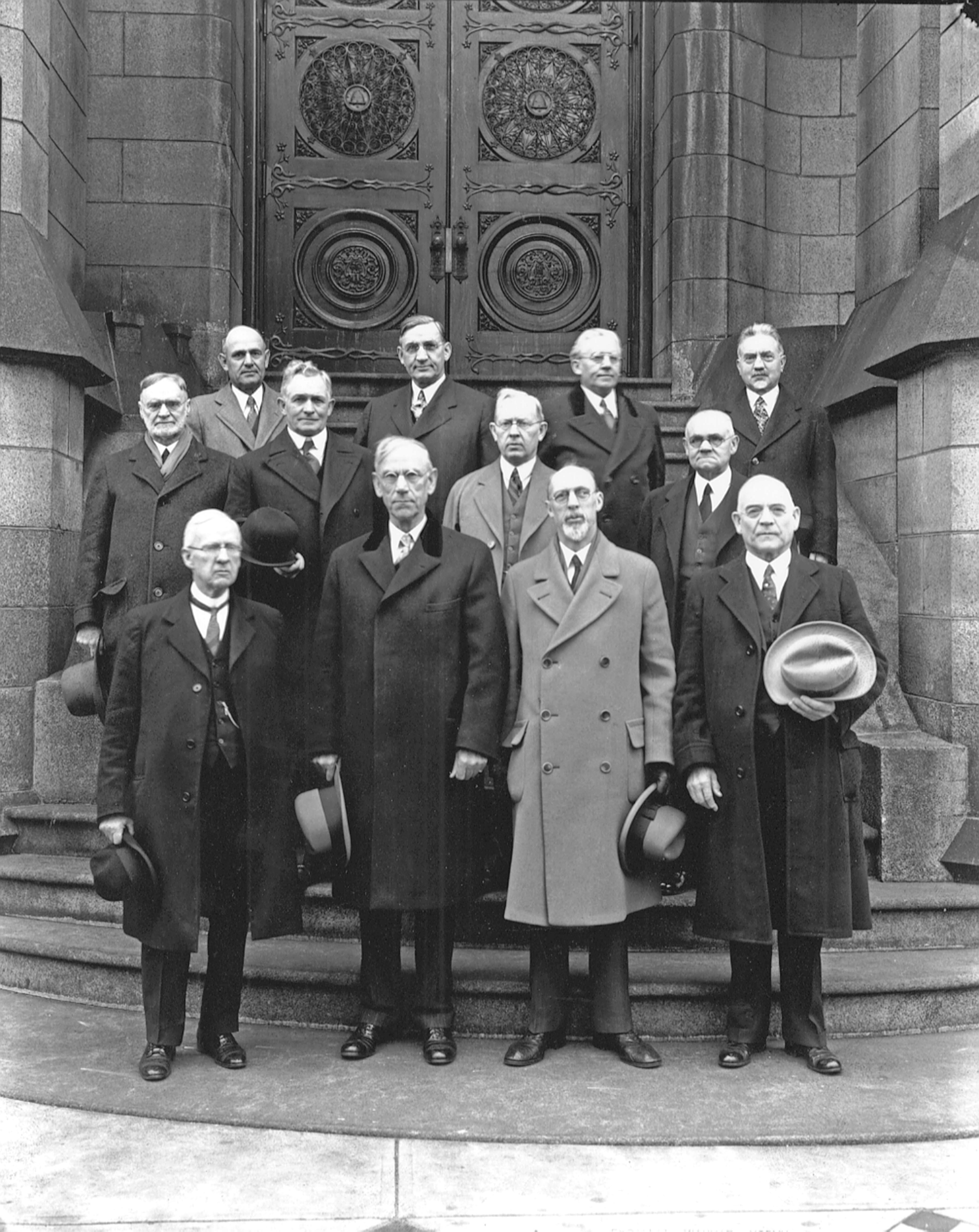

The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1931. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1931. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Men began to redefine their paternal role by the cohort they associated with on an everyday basis—their working peer group. Perhaps as men commenced to work in the factories, the role of father lost its salience. It appears that men interacted and bonded with other men and subsequently did not need their families, nor did they see themselves any longer as family men. David Blankenhorn made his mark in the 1990s by defending fatherhood and substantiating the need for men in families. He is the author of Fatherless America and The Future of Marriage. From his research on fathers, Blankenhorn substantiated his claim that during this time period, more and more men “looked outside the home for the meaning of their maleness. Masculinity became less domesticated, defined less by effective paternity and more by individual ambition and achievement. Fatherhood became a thinner social role. . . . Paternal authority declined as the fatherhood script came to be anchored in, and restricted to, two paternal tasks: head of the family and breadwinner.”[18]

Perhaps the ultimate blow to fatherhood was the Great Depression. By the 1930s, fatherhood meant breadwinning. The American perception was that income level determined paternal success. Therefore, the Depression shattered the identities of millions of men as fathers and breadwinners. Some men became depressed and suicidal because they could no longer provide for their families. Although some would argue that unemployment would bring a father closer to his children (since he would have more spare time), just the opposite proved to be true. The Great Depression actually forced family men to devote their attention to finding jobs and placed much strain on those who were already working. In many cases, fathers were forced to leave their homes and venture into distant cities to find work. Ultimately, children were dropped from their father’s calendar.

Home, then, became the scene of a man’s failure: “His children were a daily reminder that he had failed at the fundamental task of fatherhood, which left him consumed by guilt and a profound sense of inadequacy.”[19] So fathers stayed away from the very place they were needed the most—the home. As fathers neglected their families, they subsequently lost their identity while children and mothers suffered the consequences.[20]

David O. McKay viewed himself as more than a mere breadwinner. He was involved as a parent and took his paternal responsibility seriously. Even so, he still had to balance his roles as husband, father, provider, and church leader. He was an educator by trade; therefore, funds were often tight. Besides breadwinning, David also bore the heavy load of Church responsibilities. By the cultural standards during the early 1900s, David was not expected to be a nurturing father. As we explore his life, we will come to understand, however, that he was.

1930s to the 1950s

In some ways, World War II rescued many men who had failed as fathers. Primarily, the war provided men with an income. They could now support their families as the role of breadwinner was reestablished. Emotionally, the war also assisted in restoring pride and self-worth to fathers as they left their families and went overseas to “fight for their country.” During the war years, however, America became by force a “fatherless society” again. Women had to once again assume the role of mother and father. Needless to say, the war took an emotional toll on the women of America as they tried to hold their families together.

Soon after the 1940s, however, the tides appeared to change as men came home and assumed their patriarchal roles. For the most part, families were excited to have dad home. However, for many families, it was a “rough entry,” as the father had to find his way back into the family. After all, mothers had things running rather smoothly for the last few years. Even so, with some time and patience, fatherhood was rejuvenated as America moved into the next decade.

In the 1950s television personalities Ozzie Nelson and Ward Cleaver began to represent ideal fatherhood. Men’s priorities transformed due to the damaging effects of the war; they realized what they had been missing and were anxious to reestablish their roles as nurturing fathers. Subsequently, stability was restored to the American family. Only 11 percent of children born in the 1950s saw their parents’ divorce, and only 5 percent of the nation’s children were born out of wedlock.[21] Robert E. Griswold, noted historian and professor at the University of Oklahoma, commented, “Fathers who went begging for work in the 1930s now had a variety of high-paying jobs from which to choose, and with work men gained a new sense of manhood.”[22] Moreover, the healthy American family was what the war had been about, and almost every family scholar agreed that the traditional family, with a homebound mother and wage-earning father, would best maintain the familial stability needed to reestablish the traditional family in America. Hence, strong families could provide order and stability to the larger society, and a hearty society could provide an anchor to a war-torn world.

Children of the Depression became the fathers of the 1950s. These men wanted to make up for lost time. By doing so, they became involved and active in the lives of their children. Fathers began to assist their children with homework, coach little league, and occasionally make an appearance at a PTA meeting. It appeared that men were making recompense for their own deficits just a decade earlier and trying to redeem themselves from the “sins of their fathers.”

Such a paradigm shift is useful in explaining why a 1957 study found that 63 percent of 850 fathers had a positive attitude toward parenting. As men began to reconstruct their lives, fathering provided meaning and positive interactions with their children, who reinforced the paternal role. Consequently, fathers were finding fulfillment through family life. Soon, men began to read books, listen to radio programs, and attend workshops on parenting and family life.

During this time period, David O. McKay was in the First Presidency of the Church and had children as well as grandchildren at home. He embraced a new fatherhood where men were more nurturing and involved in their children’s lives. He seemed to be ahead of the curve, however, because this more kind, gentle, and involved father approach is how President McKay always did it.

David O. McKay seems to have more in common with the fathers in the ’40s and ’50s who were more nurturing and involved. Although it was a challenge for him to spend significant amounts of time with his children, when he was with them, he made the time count. He used the time he had with his children to teach them, to influence them, to laugh with them, and to make memories with them.

Notes

[1] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1965, 7.

[2] David Popenoe, Life without Father, 87.

[3] Robert L. Griswold, “Generative Fathering: A Historical Perspective,” in Generative Fathering: Beyond Deficit Perspectives, ed. Alan J. Hawkins and David C. Dollahite (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1997), 71–86.

[4] Griswold, “Generative Fathering,” in Generative Fathering, 72–73.

[5] Two other fascinating details have been noted by researcher David Blankenhorn. He explained that “in almost all cases of divorce, it was established practice to award the custody of children to fathers. [Also] throughout this period, fathers, not mothers, were the chief correspondents with children who lived away from home.” Blankenhorn, Fatherless America: Confronting Our Most Urgent Social Problem (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 13.

[6] Popenoe, Life without Father, 93.

[7] Furthermore, historians have documented that during this period of “enlightenment,” the building blocks for a marriage were no longer economically centered, but now focused on intimacy and romance. That is to say, during the 1700s (colonial or Puritan fatherhood), mate selection was based on assets and potential for economic production; thus, the marriage relationship was often considered cold and distant. However, during the 1800s, the situation changed and marital relations were built on love, trust, and even sexuality. Robert L. Griswold, Fatherhood in America: A History (New York: Basic Books, 1993).

[8] Blankenhorn, Fatherless America, 14.

[9] J. H. Pleck, “American Fathering in Historical Perspective,” in Changing Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity, ed. Michael S. Kimmel (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, 1987), 86.

[10] Blankenhorn, Fatherless America, 14.

[11] For example, Isaac Avery’s pride in his son, just four months old, was manifest in a letter to a friend: “Thomas Lenoir Avery, a young gentlemen . . . can sit alone, laugh out loud and cut other smart capers for a fellow of his age and is the handsomest of all [our] . . . children.” See Griswold, Fatherhood in America, 18.

[12] Griswold, “Generative Fathering,” in Generative Fathering, 73–74.

[13] Popenoe, Life without Father, 112.

[14] Robert R. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1967, 84.

[15] Michael E. Lamb, “The History of Research on Father Involvement: An Overview,” Marriage and Family Review 29, no. 2–3 (2000): 23–42.

[16] President Theodore Roosevelt immediately warned the country about “race suicide.” Equally alarming was the divorce rate: from 1900 to 1920 it increased 100 percent. See Popenoe, Life without Father, 115.

[17] Griswold, Fatherhood in America, 95.

[18] Blankenhorn, Fatherless America, 15.

[19] Griswold, Fatherhood in America, 44.

[20] The “fatherless” generation of the 1930s produced a generation of deficient men and delinquent children—many fathers left their “homes in disgrace while their delinquent children gathered on street corners looking for trouble.” See Griswold, Fatherhood in America, 146.

[21] Barbara Defoe Whitehead, “Dan Quayle Was Right,” Atlantic Monthly, April 1993, 47–84.

[22] Griswold, Fatherhood in America, 162.