The Temple of Herod

David Rolph Seely

David Rolph Seely, "The Temple of Herod," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 53-70.

David Rolph Seely is professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University (Provo).

The First Temple/

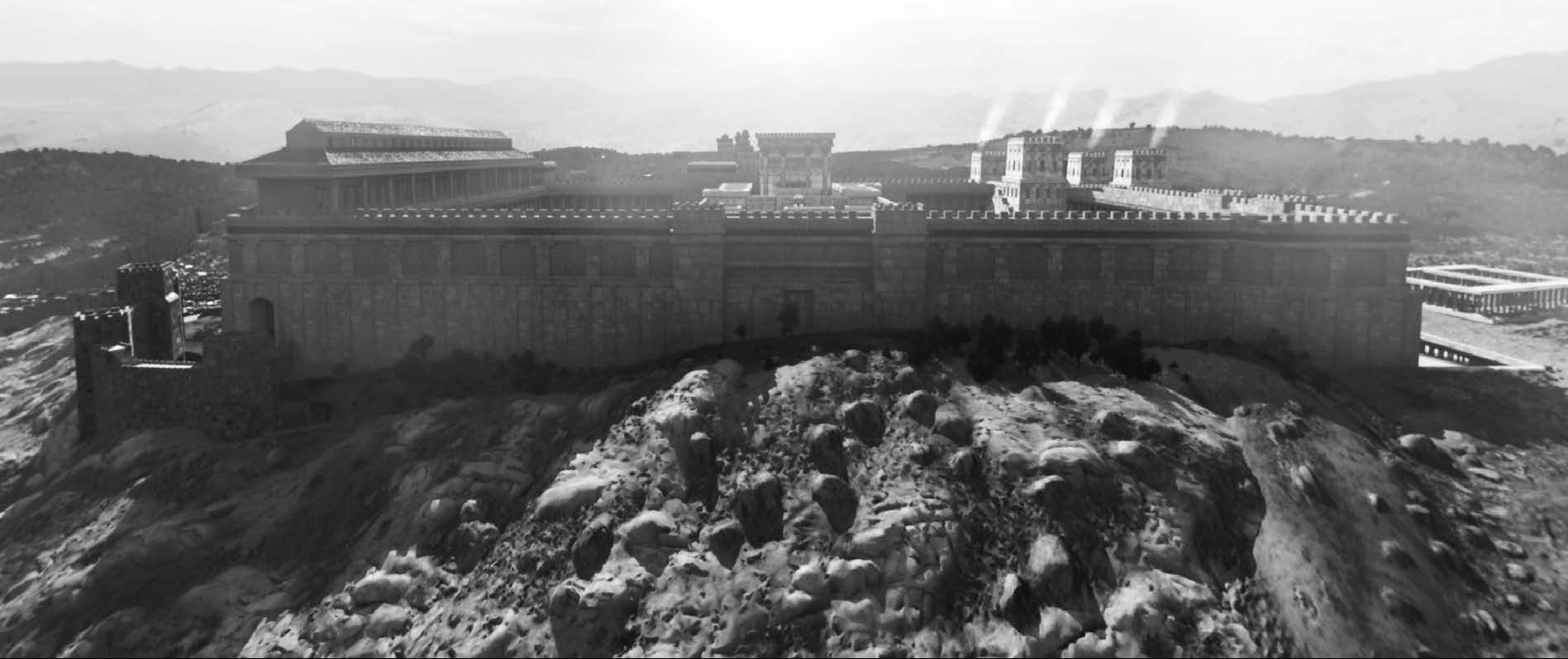

Looking Northwest to the Temple of Herod.

Looking Northwest to the Temple of Herod.

After King David conquered Jerusalem, Solomon built his splendid temple in ca. 966 BC (1 Kings 5–9 and 2 Chronicles 2–4) on the top of a hill that was was traditionally considered to be the site of Mount Moriah, where Abraham nearly sacrificed his son Isaac (2 Chronicles 3:1; Genesis 22:2). When Solomon dedicated his temple he declared, “I have surely built thee an house to dwell in” (1 Kings 8:13). In Hebrew the temple is referred to as the beth Yahweh “house of the Lord,” har habayit “mountain of the house [of the Lord],” or hekhal “palace,” indicating that the primary function and symbolism of the ancient Israelite temple was to represent where God dwelt in the midst of his people. The ark of the covenant in the Holy of Holies represented the throne of the Lord who was described as dwelling “between the cherubim” (1 Samuel 4:4; 2 Samuel 6:2). In addition to representing the presence of God, the temple represented the covenant that bound the Lord to his people (Leviticus 26:11–12), since the ark of the covenant contained the Ten Commandments written on stone tablets (Exodus 25:16).[1] According to Deuteronomy 12, after the temple was built all sacrifices were to be done only at the Jerusalem temple. Thus, the temple was a central religious, political, social, cultural, and economic institution in ancient Israel, and beginning in the days of Hezekiah and Josiah it was the only place where the ancient Israelites, under the authorization of the priests and Levites, worshipped the Lord God through sacrifices and offerings and for pilgrimage. It was also a central place for fasting, prayer, and singing hymns. The sacrifices, offerings, and furnishing of the Israelite temples such as altars, basins, veils, candlesticks, incense altars, tables for shewbread offerings, and the priestly clothing were familiar to the gentile cultures surrounding Israel.[2] The Israelite temples were unique in that they had no image of their deity.

Solomon’s temple is known as the First Temple, and it was the temple familiar to Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Lehi—prophets who warned the people that unless they repented and kept the covenant, the Lord would allow their enemies to destroy Jerusalem and scatter the people. After many generations of apostasy the Lord allowed the Assyrians to conquer and deport the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722. Judah, in spite of the reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah, also continued to disobey the covenant, and in ca. 586 BC the Lord allowed Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians to capture Jerusalem and destroy the temple and take many of the people into exile.[3]

The Second Temple/

In ca. 539 BC Cyrus the Persian conquered Babylon and granted permission to the Jews along with other exiled peoples living in Babylon to return to their homes. Cyrus granted the Jews permission to take back to Jerusalem the temple vessels that had been captured by the Babylonians and rebuild their temple (2 Chronicles 36:22; Ezra 1). Led by Zerubbabel, the Jews eventually rebuilt the temple (called Zerubbabel’s temple) and rededicated it in ca. 515 BC (Ezra 5–6); that temple would stand until ca. 20 BC when Herod dismantled it and built a new temple in its place. The phrase “Second Temple” is a designation used for both Zerubbabel’s and Herod’s temples.[4]

The people returning from exile sought to restore temple worship by erecting a replica of Solomon’s temple on the Temple Mount. However, because of poverty they were unable to adorn it with the wealth and splendor of the First Temple. The book of Ezra records that at the dedication of Zerubbabel’s temple, those who had seen the First Temple wept (Ezra 3:12). Nevertheless, the temple and the Temple Mount were enhanced by wealthy donations and by additional building projects through the Persian and Hellenistic periods.

Zerubbabel’s temple enjoyed a long period of relative tranquility from ca. 515 to 198 BC under the Persians and the Ptolemies based in Egypt. This period would end in 198 BC when the Seleucids, based in Syria, defeated the Ptolemies and took control of Yehud/

Herod’s Temple (ca. 20 BC–AD 70)

Herod (reigned from ca. 40–4 BC) was one of the great builders of antiquity; his goal in rebuilding the temple was to create one of the most magnificent buildings in his day and in the process to try to please his subjects, the Jews. Herod began to build his temple in ca. 20 BC—although the temple was not completed until ca. AD 63. According to Josephus, Herod believed that building the temple would be a task great enough “to assure his eternal remembrance” (Antiquities 15.380). Herod’s temple was one of the wonders of the ancient world—a beautiful building and a marvel of engineering. Josephus, who was an eyewitness of the temple, reported, “The exterior of the building lacked nothing that could astound either mind or eye. . . . To approaching strangers it appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not over laid with gold was of purest white” (Jewish War 5.222–23).

Ancient sources pertaining to Herod’s temple include the writings of Josephus (ca. AD 37–100)[6] and Philo (ca. 20 BC–AD 50)[7]—both eyewitnesses of the temple, and tractates in the Mishnah: Middoth (“measurements”), Tamid (“the permanent sacrifice”), Yoma (“the Day of Atonement”), and Shekalim (“the shekel dues”).[8] While there is no archaeological evidence of the temple proper, there are many architectural and archaeological evidences of the Temple Mount, including several important inscriptions.[9]

Looking West to the Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives.

Looking West to the Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives.

Josephus records that Herod, in the eighteenth year of his reign (20–19 BC), gave a speech to the people in which he proposed to rebuild Zerubbabel’s temple in gratitude for the fact that he had, “by the will of God, brought the Jewish nation to such a state of prosperity as it has never known before” (Antiquities 15.383). His envisioned rebuilding project was a delicate operation since it would involve the complete demolition of Zerubbabel’s temple and the expeditious building of the new temple.[10] In order to assuage the fears of the people that he would not build the new temple after demolishing the old one, in consultation with religious leaders Herod first prepared all the necessary materials for his temple. Next, he allegedly appointed ten thousand men to rebuild the temple and specifically trained a thousand priests as builders and stonemasons so they would be able to carry out the construction in the inner courts of the temple where nonpriests would not be allowed to enter (Antiquities 15.390–91). For the erection of the altar, Herod followed the biblical prescription (Exodus 20:22) and used stones quarried nearby not touched by iron (Jewish War 5.225). The temple proper was built in a year and a half and the surrounding porticos and courtyards in eight years (Antiquities 15.420–21). However, construction on the whole complex continued for more than eighty years from the time it was begun and was only completed in AD 63 (Antiquities 20.219; compare John 2:19).

From the descriptions preserved in Josephus and the Mishnah, correlated with the remains and the excavations around the Temple Mount, it is possible to reconstruct what the mount and the temple looked like with some degree of confidence.[11] The dimensions of Herod’s temple are given in cubits and/

Herod’s temple mount

Solomon’s temple and Zerubbabel’s temple, including the Hasmonean additions, were confined to the top of the hill called Mount Moriah, bounded on the east and south by the Kidron Valley and to the west by the Tyropoean Valley. The temple faced east toward the Mount of Olives. To the north of the mount was the Roman Antonia Fortress, and to the west and south was the city of Jerusalem. In order to enlarge the sacred platform, Herod expanded the area of the Temple Mount to the south and west by fill and erecting a series of arched vaults. He thus doubled the size of Solomon’s temple mount.[13] According to the Mishnah, Solomon’s temple mount was a square of 500 cubits on each side (861 feet/

Temple of Herod looking northwest from the Court of the Gentiles.

Temple of Herod looking northwest from the Court of the Gentiles.

Herod’s temple precinct was demarcated by fences and gates into concentric rings of successive holiness. The outer courtyard was called the Court of the Gentiles—here all nations were invited to come and worship the Lord. This space was open to Jews and Gentiles. Around the perimeter of the Court of the Gentiles was a portico where people could gather and teach or be taught. Along the south wall (some believe along the east wall) of this court was a long colonnaded porch forming a basilica-like room running east and west with rows of 162 beautiful columns with Corinthian capitals. Called the Royal Stoa, it is probably Solomon’s porch of the New Testament (John 10:23). The Court of the Gentiles was separated by a wall from the court where only Israelite men and women were permitted to go. Gentiles were forbidden from entering this inner court. Posted around this barrier were signs warning Gentiles not to pass on pain of death. Two of these signs have been found—one contained the entire inscription reading: “No Gentile shall enter inward of the partition and barrier around the Temple, and whoever is caught shall be responsible to himself for his subsequent death.”[16] Apparently temple officials were given the right to enforce this ban on foreigners in this sacred space. The seriousness of the offense of Gentiles crossing the barrier is dramatized by the story in Acts where Paul was falsely accused of bringing non-Jews past this enclosure and the mob attempted to kill him (Acts 21:27–32). The temple proper was approached from the east by passing through the Court of Women—where men and women could go to observe the sacrifices through the gate. A long narrow court stood between the Court of the Women and the altar called the Court of the Israelites; there only Jewish men could go. Beyond that court only the priests and Levites could serve in the area around the altar; only the priests could enter the temple, and only the high priest could enter the Holy of Holies once a year.

Archaeological evidence has determined that there were eight gates to Herod’s temple mount from the surrounding city: one in the east, two in the south, four in the west, and one in the north. Archaeological remains of ritual baths or mikvahs have been excavated near several of these gates, indicating that the Jews would ritually purify themselves before coming onto the Temple Mount. The most common entrance for pilgrims coming to the temple were the two splendid gates in the south, called the Double Gate and the Triple Gate, that were approached by a monumental stairway.

The temple and temple worship

Herod’s temple represented the house of the Lord and was the center of Israelite worship as legislated in the Old Testament and enhanced by centuries of Jewish tradition.[17] Temple worship consisted of a complex series of sacrifices and offerings that could only be offered at the temple. Additionally, the temple was the focal point of the Jewish festivals, including the three pilgrimage festivals that all Jews throughout the world were required to celebrate at the temple in Jerusalem.

Court of the Women looking West to the Nicanor Gate, Court of the Israelites, and Court of the Priests.

Court of the Women looking West to the Nicanor Gate, Court of the Israelites, and Court of the Priests.

The temple proper was situated near the middle of the inner courtyard, facing east, and surrounded by a wall. Jewish men and women could pass from the east through the Beautiful Gate (Acts 3:2) to enter a square courtyard in front of the temple called the Court of the Women, where, Josephus records, “[we] who were ritually clean used to pass with our wives” (Antiquities 15.418). Just inside this gate, chests were placed for the collection of monetary offerings where the widow offered her mite (Luke 21:1–4). Four large lampstands were erected in this court, each with four bowls, to light the temple—especially at the Feast of Tabernacles.

Men and women congregated in the Court of the Women to observe through the gate the priests offering the sacrifices at the altar and to receive the priestly benediction. Here Jewish men and women could participate in temple worship through prayer, fasting, and hymns. Proceeding to the west, Israelite men climbed fifteen curved stairs and entered into the narrow Court of the Israelites separated from the Court of the Priests by a line in the pavement. Standing in the Court of the Israelites, one could see the large stone altar 40 feet [12 meters] square and 15 feet [4.5 meters] high[18] upon which the priests offered the sacrifices. A ramp led to the top of the altar that had horns at the four corners. The priests offered regular daily offerings at the temple on behalf of all Israel and also assisted in the many offerings brought by individuals to the temple. Under the law of Moses there were five major sacrifices (Leviticus 1–7). The burnt offering was the sacrifice of an animal that was completely burned on the altar—the smoke symbolized the offering ascending into heaven. In addition to the burnt offering, the sin offering and trespass offering were connected with the offering of blood for atonement from sin and ritual impurity (Leviticus 17:11). The meal offering was offered for thanksgiving. The peace offering represented a communal meal—divided into three portions: one given to the Lord, one given to the priests, and one taken home and eaten by the offerer. To the north of the altar was the Place of Slaughtering where the sacrificial animals were butchered and skinned. Between the altar and the temple was a large bronze laver providing water for washing. Each of the priests ritually washed their hands and feet before and after officiating at the temple (Exodus 30:20–21).

Court of the Priests.

Court of the Priests.

According to the Mishnah Herod’s temple was 100 cubits (172 feet/

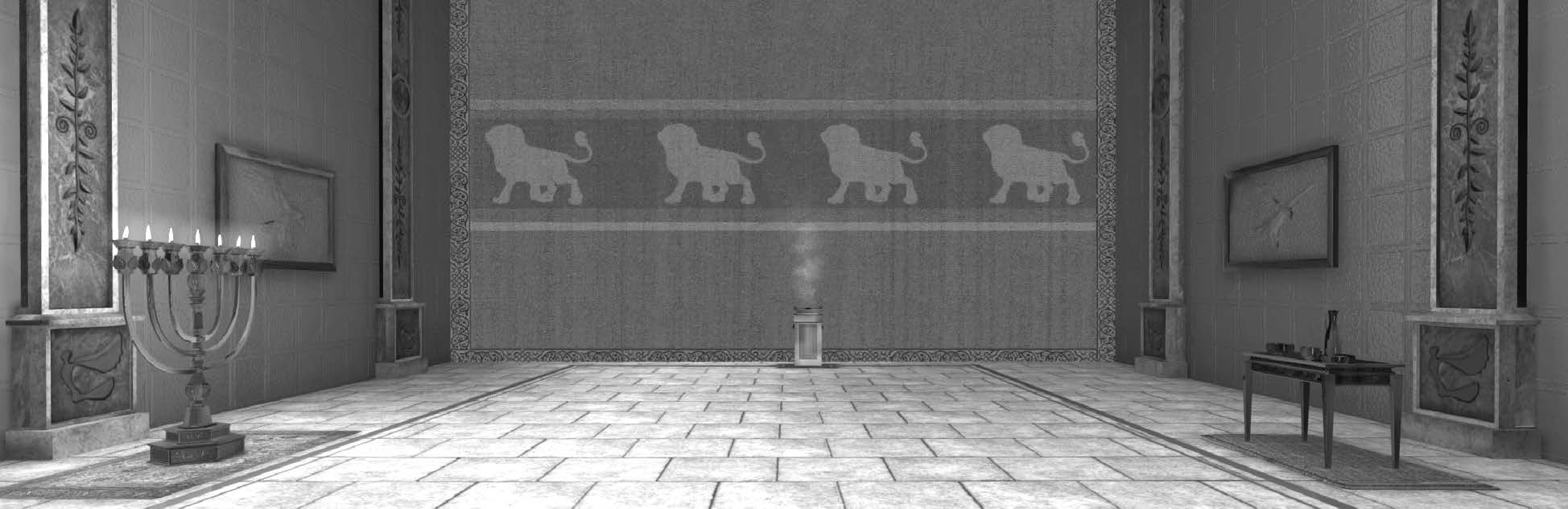

A large veil of several colors hung in front of the doors at the entrance to the Holy Place. Passing through the veil, one entered the Holy Place. The Holy Place and the Holy of Holies together comprised one large rectangular room completely covered with plates of gold separated only by the veil of the temple. In the Holy Place there were three furnishings: the table for the bread of the presence (shewbread), the seven-branched lampstand or menorah, and the incense altar. Each week the tribes of Israel offered twelve loaves of bread to the Lord on the table, and at the end of the week the priests ate them on the Sabbath. This symbolized a sacred meal shared by the offerer, the Lord, and the priest. The menorah is described as being shaped like a tree consisting of a central axis and three branches on each side, making seven branches in all. At the top of each branch was a cup filled with olive oil that functioned as a lamp. Because of its form, the menorah is often associated with the tree of life.[20] The lamp was the only source of light in the temple. Each day the priests entered the Holy Place to light and trim the lamps and to light the incense. The golden altar of incense stood next to the veil of the temple. Incense was expensive and was thus seen as a sacrifice, and the sweet odor helped to counteract the smells of sacrifice at the temple. It also effectively created an otherworldly environment suggesting the presence of God. In the scriptures the burning of incense symbolized prayer (Psalm 141:2; Revelation 5:8; 8:4). In the New Testament Zecharias was officiating at the incense altar, with a prayer in his heart, when Gabriel appeared to him to announce the birth of John the Baptist (Luke 1:5–23).

The Holy Place with Menorah (left), Altar of Incense (center), and Table for the Bread of Presence (right).

The Holy Place with Menorah (left), Altar of Incense (center), and Table for the Bread of Presence (right).

Separating the Holy Place from the Holy of Holies was another veil. The veil of the temple consisted of two curtains hung about 18 inches apart. The outer curtain was looped up on the south side, and the inner one on the north side provided a corridor for the high priest to walk through on the day that he entered the Holy of Holies so that no one else could see into the Holy of Holies. The Holy of Holies was a square-shaped room 20 cubits (34.4 feet, 10.50 meters) in width and length with a height of 40 cubits (69 feet, 21 meters) (Middot 4.7). The interior was covered with plates of beaten gold. In the tabernacle and Solomon’s temple the original focal point of the worship of Israel was the ark of the covenant covered by the mercy seat with two cherubim representing the throne of God and designating his presence. In the Second Temple the Holy of Holies was empty since the ark of the covenant and the cherubim had disappeared in the course of the destruction of Solomon’s temple in 586 BC.[21] Rabbinic tradition identified a stone on the floor of the Holy of Holies, rising to a height of three-finger breadths, as the “foundation stone” (eben shetiyyah)—the very stone with which the creation of the world began (Mishnah Yoma 5:1). On the Day of Atonement in Old Testament times, the high priest sprinkled the blood of the sacrifice on the mercy seat of the ark in order to make atonement. In Herod’s temple the high priest sprinkled the blood of the sacrifice on this stone. The Mishnaic tractate Middot relates that in the upper story of the Holy of Holies were openings through which they could let down workmen in boxes to assist in the maintenance of this space (Middot 4.5).

The festivals

The most important holy day in ancient Israel was the Sabbath (Saturday) and this day was celebrated by changing the twelve loaves of the bread of the presence, with the priests eating the week-old bread, and by offering a double sacrifice at the temple. According to biblical law (Exodus 23, 34, and Deuteronomy 16), three times a year all Jewish males were required to appear “before the Lord” (i.e., at the temple). The three festivals are Passover, Shavuot (Weeks/

Countless multitudes from countless cities come, some over land, others over sea, from east and west and north and south at every feast. They take the temple for their port as a general haven and safe refuge from the bustle of the great turmoil of life, and there they seek to find calm weather, and released from the cares whose yoke has been heavy upon them from their earliest years, to enjoy a brief breathing-space in scenes of genial cheerfulness.[22]

The temple had a function for each of these festivals. At Passover, which celebrated the exodus from Egypt, the Passover lambs were sacrificed at the temple and then taken to the homes, where the festival was celebrated by families. Fifty days later at the Festival of Weeks, or Pentecost (compare Acts 2), which celebrated the first harvest, individuals brought firstfruit offerings to the temple to be offered on the altar. The Feast of Tabernacles commemorated the wanderings in the wilderness, and the people were commanded to live for seven days in booths and to eat each day the bounty of the harvest with thanksgiving. In addition, a procession was held with the waving of palm branches, ethrog, and lulav. Based on descriptions in extrabiblical Jewish traditions (Mishnah, Sukkah “The Feast of Tabernacles” 4–5), an elaborate procession of water was held in conjunction with Tabernacles in which the priests drew water from the Siloam pool and brought it up in a happy procession to pour on the altar of the temple (compare John 7). At this festival the four great menorahs in the Court of the Women were lit, illuminating the whole of Jerusalem.

The most solemn yearly festival celebrated at the temple was the Day of Atonement described in Leviticus 16. This festival was held on the tenth day of the seventh month, which began with Rosh Hashanah initiating the fall new year, four days before the Feast of Tabernacles. On this day the high priest led Israel in a series of sacrifices that would atone for sin and ritual impurity through the ritual of the two goats. One goat would be sacrificed, and upon the head of the other goat the sins of the people would be pronounced. This goat, known as the “scapegoat,” would be sent into the wilderness. Then the high priest, as the climax of this ritual, was able to enter into the Holy of Holies to sprinkle the blood of the sacrifice on the floor, thus effecting the forgiveness of sin and ritual impurity and resulting in reconciliation or at-one-ment between God and humans.

Clothing of the high priest

While serving in the temple, the priests wore special clothing consisting of pantaloons, a white robe, an embroidered belt, and a round hat. In addition, the high priest wore four additional vestments (Exodus 28:3–43). First, he wore a long blue robe with embroidered pomegranates and golden bells hanging from the bottom. Next, he wore an apron encircling the body called an ephod held in place by two shoulder straps, each bearing an onyx stone inscribed with the names of six tribes of Israel (Exodus 28:6–10). Connected to the ephod was a breastplate containing twelve stones representing the twelve tribes of Israel (Exodus 28:15–28). Thus, when the high priest officiated at the temple he did so bearing the tribes of Israel symbolically before the Lord. An embroidered flap of the breastplate folded behind forming a pouch wherein the high priest kept the divinatory instruments (the Urim and Thummim), representing the means of inquiring and receiving the will of the Lord. Finally, he wore a hat (called a turban) and a pure gold plate inscribed “Holiness to the Lord” (Exodus 28:36–38).

Symbolism of the temple

The biblical descriptions of the furnishings of the temple rarely specify the symbolic meaning of the temple or its furnishings. However, in the Hellenistic-Roman period Philo and Josephus set forth various interpretations giving cosmic significance to various aspects of the temple. Philo interpreted the high priestly clothing as representing the cosmos with the violet robe representing the air, the embroidered flowers the earth, and the pomegranates the water. Similarly, Josephus interpreted the seven lamps of the menorah as the seven planets, the twelve loaves of the bread of the presence as the circle of the year and the Zodiac, and the thirteen spices of the incense on the incense altar coming from the sea and the land as signifying “all things are of God and for God” (Jewish War 5.216–18). Likewise, Josephus ascribed cosmic significance to the veil at the entrance of the temple: “The scarlet seemed emblematical of fire, the fine linen of the earth, the blue of the air, and the purple of the sea; the comparison in two cases being suggested by their color, and in that of the fine linen and purple by their origin, as the one is produced by the earth and the other by the sea. On this tapestry was portrayed a panorama of the heavens, the signs of the Zodiac excepted” (Jewish War 5.213). And he described the Holy of Holies, “In this stood nothing whatever: unapproachable, inviolable, invisible to all” (Jewish War 5.219).

The New Testament and the Temple

The temple is a central feature in the Gospel narratives of the life and ministry of Jesus. The Gospel of Luke opens in the temple with the appearance of the angel Gabriel to the priest Zacharias as he was officiating at the incense altar in the Holy Place (Luke 1:5–24), and the Gospel of Luke ends with a note that the disciples of Jesus, after his ascension “were continually in the temple, praising and blessing God” (Luke 24:53). Forty days after the birth of Jesus, Mary and Joseph took him to the temple to offer the burnt and sin offerings as prescribed by the law of Moses (Leviticus 12:6–8), and there they met Anna and Simeon, who both proclaimed Jesus’s messiahship (Luke 2:28–38). The only story of the youth of Jesus in the Gospels recounts how as a twelve-year-old, after being left behind in Jerusalem following the Passover feast, he was found by his parents conversing with the elders at the temple (Luke 2:41–52). And as part of the temptations Jesus was transported by the Spirit (JST) to “a pinnacle of the temple” where Satan tempted him to throw himself off so that the angels would come and save him (Luke 4:9–11; Matthew 4:5). The Gospel of John records that Jesus cleansed the temple at the outset of his ministry as a symbol that he came in power and with authority, and Jesus used this occasion to teach of his eventual death and resurrection from the dead (John 2:13–25). Following this cleansing of the temple, the Jews asked Jesus for a sign of his authority. According to the Gospel of John: “Jesus answered and said unto them, Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up. Then said the Jews, Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days? But he spake of the temple of his body” (John 2:19–22).

Throughout his ministry Jesus came to Jerusalem each year to celebrate Passover. He regularly taught and healed at the temple (Matthew 21:14–15). In the temple precincts he observed the widow offering her alms and taught the lesson of the widow’s mite (Mark 12:41–44). During the Feast of Dedication (Hanukkah) John records that Jesus taught in the porch of Solomon (John 10:22). According to the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), Jesus cleansed the temple at the end of his ministry. During the passion week Jesus went to the temple, whose precincts were crowded with tens of thousands of pilgrims who had come to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover. There he made a whip and drove out those “that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the money-changers, and the seats of them that sold doves” (Matthew 21:12; Luke 19:45–47). Jesus explained his act by quoting Jeremiah 7:11: “My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves” (Matthew 20:13). More than six hundred years earlier, Jeremiah had come to the temple and had warned Israel that their unrepentant hypocrisy and sin would bring the destruction of the temple by the Babylonians. Jesus’s reference to Jeremiah was thus an ominous foreshadowing of the future destruction of the temple by the Romans if the people did not repent. And finally at the moment when Jesus died on the cross, the veil of the Holy of Holies in the temple was rent in two (Luke 23:45), symbolizing that through his atonement all would be able to enter into the presence of God.

The Gospel of John specifically portrays Jesus as a fulfillment of some of the symbols of the temple and its festivals. A passage at the beginning of John describes Jesus as the tabernacle when it says, “and the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). The English word dwelt is derived from the Greek verb skēnoō used in reference to the Old Testament tabernacle that literally means “he tabernacled” or “pitched his tent” among us. Thus, through Jesus, God came to dwell among his people just as God had made his presence known among his people anciently in the tabernacle, in which he could “dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8). When John the Baptist first saw Jesus he announced him as “the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world” (John 1:29), an allusion to the sacrifice of the lambs at the temple. And in the Gospel of John Jesus is crucified on the cross on the day of Passover when the paschal lambs were being sacrificed at the temple (John 19:31–37).[23] The Feast of Tabernacles included a ceremony of drawing water from the Siloam pool and pouring it on the altar of the temple and also of lighting the four great menorahs in the Court of the Women. Jesus may have been comparing himself to these symbols of water and light when in the context of this festival (John 7:2) he taught: “He that believeth on me, as the scripture hath said, out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water” (John 7:38), and also “I am the light of the world” (John 8:12).

Following the death of Jesus, the book of Acts records that the apostles and followers of Jesus continued to teach and worship at the temple. A pivotal event occurred fifty days after the death of Jesus during the pilgrimage feast of Pentecost, in which many Jews had come to Jerusalem to offer up to God their firstfruit harvests at the temple. On that day the Holy Spirit descended on the apostles like a mighty wind and tongues of fire, causing them to speak in tongues. Three thousand people followed Peter’s invitation to repent and be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ—fulfilling the symbols of Pentecost as the firstfruit harvest of Christianity (Acts 2). Acts describes the early saints as “continuing daily with one accord in the temple” (Acts 2:46). Following Pentecost Peter and John healed the lame man at the temple (Acts 3) and continued to teach the good news of the resurrected Jesus at the temple, leading to their arrest and imprisonment (Acts 4:1–3).

The sanctity of the temple for the earliest Christians is further reflected in a number of stories recorded in Acts. Paul and the other apostles prayed and worshipped at the temple, performing the required purification rituals and offering sacrifice there (Acts 21:26). Paul insists that he never “offended” “against the temple,” implying he accepted its sanctity (Acts 25:8). Indeed, Paul’s second vision of Christ occurred at the temple (Acts 22:14–21), strongly suggesting the continued special sanctity of the temple where God still appeared to men.

The Epistle to the Hebrews explains the atonement of Jesus Christ in terms of the temple. Hebrews 8–9 portrays Jesus as the high priest and explains his act of reconciliation between God and humans in terms of the ritual of the Day of Atonement when the high priest would take the blood of the sacrifice into the Holy of Holies and sprinkle it on the mercy seat, thereby reconciling God and his children (Leviticus 16). In Hebrews this atonement occurred not in the temple on earth but in the heavenly temple made without hands: “For Christ is not entered into the holy places made with hands, which are the figures of the true; but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God for us” (Hebrews 9:24).

The book of Revelation contains John the Revelator’s vision of the new Jerusalem. In this vision John looked for the temple in this heavenly city and then said, “And I saw no temple therein: for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are the temple of it” (Revelation 21:22). In this vision the ultimate fulfillment of the temple was realized by the continuing presence of the Father and the Son in the heavenly city.

The Temple in First-Century Judaism and Christianity

The Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem in 63 BC, and Judea became a vassal state to Rome. Herod the Great ruled as a loyal subject to Rome, and yet the splendid temple he erected generally enjoyed a fiercely defended autonomy broken only by incidents where Roman rulers demanded the erection of images of themselves or their pagan gods requiring the Jews to worship them.[24] As a symbol of this balance of power under Roman rule, a daily sacrifice was offered for the welfare of the Roman emperor at the temple consisting of two lambs and an ox. The sacrifice was initiated and financed by Augustus but was defiantly abandoned at the beginning of the Jewish revolt in AD 66 (Philo, The Embassy to Gaius 157, 317–19).

The major sects of Judaism and early Christianity had their own distinctive relationships to the institution of the temple and its priesthood and rituals. The Sadducees were the aristocratic priestly families who controlled and administrated many aspects of the temple. When the temple was destroyed, the Sadducees lost the foundation of their livelihood and their base of power among the people. While priestly traditions survived for a time in the synagogue traditions, eventually the Sadducees without a temple were eclipsed by the Pharisees.

The Pharisees did not oppose participation in the temple in spite of their opposition to the control of the Sadducees. The Pharisees, however, owed their allegiance to oral law and thus found their relationship with the temple more flexible. Through oral law they would be able to forge religious practices that could survive without the temple. A Jewish legend records how Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai, who found himself trapped in Jerusalem during the Roman siege, realized the temple was going to be destroyed. He had himself hidden in a coffin in order to leave the city. He was taken before the military commander Vespasian, who eventually became a Roman emperor. The rabbi asked Vespasian to give him Yavneh, a city where he founded a rabbinical academy that preserved the Sanhedrin and the ongoing process of oral tradition that would result in the publication of the Mishnah (Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 56).

Eventually the sect of the Pharisees transitioned into rabbinic Judaism, which became mainstream Judaism to the present day. With time Pharisaic Judaism was able to promote institutions that continued worship in the absence of the sacrificial system of the temple. A well-known story in the Midrash tells of Rabbi ben Zakkai, who, when walking by the ruins of the temple, said to his disciple, “My son, do not be grieved, for we have another atonement that is just like it. And which is it? Acts of loving-kindness, as it is said, ‘For I desire loving-kindness, and not sacrifice’ [Hosea 6:6]” (Avot de-Rabbi Natan 4.21).[25] With time other rabbis noted that prayer, study, and acts of loving-kindness are pleasing to the Lord like sacrifice.[26]

The Samaritans claimed to be remnants of the northern ten tribes. They preserved an ancient tradition in their version of the Torah called the Samaritan Pentateuch that commanded the temple be built on Mount Gerizim. According to Josephus the Samaritans built their temple there sometime in the period of Alexander the Great (Antiquities 11.310–11), and it remained a center of their religious community and a competing temple to the Jerusalem temple until the Samaritan temple was destroyed by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in 129 BC (Antiquities 13.254–56).[27] The age-old conflict between the Jews and Samaritans was exacerbated by the Jewish refusal to allow the Samaritans to help with the rebuilding of Zerubbael’s temple in ca. 515 BC. The destruction of the Samaritan temple in 129 BC was another one of the defining incidents leading to the division and continued animosity between the Jews and Samaritans as reflected in the New Testament. This dispute over the temple provides the background of the conversation Jesus had with the Samaritan woman in John 4. To this day Samaritans continue to live near Mount Gerizim and offer the yearly Passover sacrifice in the vicinity of their temple site.

Most scholars believe that the Qumran community reflected in the Dead Sea Scrolls were the Essenes (see chapter 7). According to ancient historians, as well as some of the documents from Qumran, the Essenes believed that the Jerusalem priesthood that administrated the temple was corrupt and that the sacrificial system and the calendar were also corrupt. Thus, while the Essenes passionately believed in the temple, they did not participate in its rituals in Jerusalem. Some scholars argue that they saw themselves as a community representing the temple.[28] While they may have rejected the Jerusalem temple in their time, they had a strong belief in and love for the institution of the temple. One of the significant finds in the Dead Sea Scrolls is the Temple Scroll, believed by the Qumran sect to be scripture that describes the plans and the legal requirements for a future eschatological temple.[29]

Christians initially continued worshipping at the Jerusalem temple and living the law of Moses, but eventually it became clear, following the Council of Jerusalem, that one did not have to become a Jew to become a Christian (Acts 15; compare Galatians 2); therefore most Christians began to distance themselves from the temple. Following the destruction of the temple in AD 70, Christianity generally adopted the point of view that the church was a temple. Based on passages of scripture in the writings of Paul like “Know ye not that ye are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you” (1 Corinthians 3:16), and “For we know that if our earthly house of this tabernacle were dissolved, we have a building of God, an house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens” (2 Corinthians 5:1). Christians came to view the individual believer and the church as a community of believers functioning as the new temple of God.[30]

Destruction of the Temple

In the final week of his ministry, speaking to the apostles on the Mount of Olives, Jesus prophesied the destruction of the temple: “Verily I say unto you, there shall not be left here, upon this temple, one stone upon another that shall not be thrown down” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:3; compare Matthew 24:1–2). In this prophecy Jesus also quoted the prophecy of Daniel of the “abomination of desolation” connected with the destruction of Jerusalem and the desecration of the temple, and he advised those who wished to be preserved to “stand in the holy place” and “flee into the mountains” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:12–13; compare Matthew 24:15–16). Eusebius recounted that the saints in Jerusalem were spared from the destruction of Jerusalem by fleeing across the Jordan River to Pella (Church History 3, 5, 3).

The temple became the focal point of the conflict between the governing Romans and the vassal Jews that lasted from AD 66 to 70 when Titus and the Roman armies besieged and destroyed Jerusalem and the temple. As Jesus had prophesied, the temple was burned and destroyed, leaving a pile of rubble. The historian Josephus recorded the Roman destruction following the burning of the temple: “Caesar ordered the whole city and the temple to be razed to the ground.” He further noted that the city “was so thoroughly laid even with the ground by those that dug it up to the foundation, that there was left nothing to make those that came thither believe it had ever been inhabited” (Jewish War 7.1.3). The Jews were eventually driven from Jerusalem and were left without a temple.

Many of the furnishings of the temple were destroyed, though several of the implements—the trumpets, the table of the bread of the presence, and the lampstand—were preserved and taken to Rome, where their images were captured in the relief on the Arch of Titus in Rome built to commemorate Titus’s triumph. Various implements from the temple, including the menorah and the shewbread table, were preserved for many years in Rome in Vespasian’s Temple of Peace.[31]

The final echo of the temple in the Roman period is found in the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Simon Bar Kokhba (“son of the star”) was a Jewish claimant to the title of messiah who led an unsuccessful revolt against the Romans in AD 132–135. He issued coins depicting the façade of the temple, suggesting that the rebuilding of the sacred building was an integral part of Bar Kokhba’s rebellion. Bar Kokhba was heralded as the Messiah by numerous prominent Jewish rabbis, including Akiba, and thus many Jews gathered to his rebellion. The devastating defeat of Bar Kokhba led to the banning of Jews from even living in Jerusalem.

The destruction of the temple was pivotal for Jews and Christians alike. For the Jews the temple of Herod was a tangible symbol of their religion that made it possible to fulfill the laws of sacrifice in the law of Moses. With its destruction came the loss of the center of their religion, and Judaism would have to develop ways of worship to replace or compensate for the rituals and ordinances—most notably sacrifice and the celebration of the festivals—that could formerly be done only at the temple. Christians would have to decide what their proper relationship was to the temple—whether they needed an actual earthly building or if Jesus had in some way done away with the need for a physical temple. However, both Jews and Christians would continue to read and study the canonical books of their religions, including the prophecies in the Old Testament about the future restoration and rebuilding of the temple. Amos prophesied, “In that day I will raise up the tabernacle of David that is fallen, . . . and I will build it as in the days of old” (Amos 9:11). Ezekiel has a vision of the future temple complete with the plans in Ezekiel 40–48. And Isaiah prophesied, “And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, . . . and many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob” (Isaiah 2:2–3).

Notes

[1] According to Deuteronomy 31:24–26, a scroll containing the law was also placed beside the ark of the covenant.

[2] Many aspects of temple worship were common in ancient Near Eastern cultures. For a typology of some of these features, see John M. Lundquist, “What Is a Temple: A Preliminary Typology,” in The Quest for the Kingdom of God: Studies in Honor of George E. Mendenhall, ed. H. B. Huffmon, F. A. Spina, and A. R. W. Green (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1983), 205–19.

[3] For a review of the history and theology of the Israelite temples, see Menahem Haran, Temples and Temple Service in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978); Margaret Barker, The Gate of Heaven: The History and Symbolism of the Temple in Jerusalem (London: SPCK, 1991); William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely, Solomon’s Temple in Myth and History (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007); and John M. Lundquist, The Temple of Jerusalem: Past, Present, and Future (Westport, CN: Praeger, 2008).

[4] A collection of the extrabiblical sources for the Second Temple can be found in C. T. R. Hayward, The Jewish Temple: A Non-Biblical Sourcebook (New York: Routledge, 1996).

[5] Quotations of Josephus’s works throughout are taken from Josephus, Loeb Classical Library edition, trans. H. St. J. Thackery, Ralph Marcus, Allen Wikgren, L.H. Feldman (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1926–64).

[6] Josephus was from a priestly family and therefore claimed to have intimate knowledge of Herod’s temple. He wrote two lengthy and sometimes parallel descriptions of the temple and the Temple Mount in Antiquities 15.380–425 and Jewish War 5.184–247.

[7] Philo’s references to the temple are found scattered throughout his writings. A convenient collection can be found in Hayward, Jewish Temple, 108–41.

[8] A reputable English translation of the Mishnah can be found in Herbert Danby, The Mishnah (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933).

[9] Descriptions and analysis of the textual and archaeological data relating to the Temple Mount can be found in Benjamin Mazar, The Mountain of the Lord (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1975); Lee I. Levine, Jerusalem: Portrait of the City in the Second Temple Period (538 B.C.E–70 C.E) (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2002): Leen Ritmeyer, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006); Eilat Mazar, The Complete Guide to the Temple Mount Excavations (Jerusalem: Shoham Academic Research and Publication, 2012). An excellent description of the history of the Temple Mount is Oleg Grabar and Benjamin Z. Kedar, eds., Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Jerusalem’s Sacred Esplanade (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010).

[10] An historical review of Herod’s rebuilding the Second Temple can be found in Ehud Netzer, The Architecture of Herod the Great Builder (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006), 137–78; reprinted in paperback by Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2006.

[11] In Josephus and elsewhere in ancient sources, the Greek word temenos is used to describe the sacred precinct containing a temple. The King James Version of the New Testament uses the English term temple to translate two different Greek words: naos, which means “house” and refers to the temple proper, and hieron, which means “sanctuary” and refers to the whole temple complex. Usually the reader can tell from the context which meaning is intended.

[12] The descriptions in Josephus and the Mishnah occasionally show discrepancies. For a discussion and possible solutions to these discrepancies see Ritmeyer, The Quest, 139–45.

[13] Ritmeyer, Quest, 168, 233.

[14] Mazar, Mountain of the Lord, 119.

[15] Lundquist, Temple of Jerusalem, 103–4.

[16] Elias J. Bickerman, “Warning Inscription of Herod's Temple,” Jewish Quarterly Review 37 (1946/

[17] For an overview of the temple and temple worship at the time of Jesus, see Alfred Edersheim, The Temple: Its Ministry and Services as They Were at the Time of Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1997) and Randall Price, Rose Guide to the Temple (Torrance, CA: Rose Publishing, 2012); and Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer, The Ritual of the Temple in the Time of Jesus (Jerusalem: Carta, 2002).

[18] Jewish War 5.225 and Middot 3.1.

[19] There are some discrepancies in the ancient sources about the dimensions of Herod’s temple. See Ritmeyer, Quest, 77–400, for a complete description of the temple according to the Mishnah.

[20] Leon Yarden, The Tree of Light (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971), 35.

[21] The last mention of the ark is from the time of Josiah (2 Chronicles 35:1). Because no mention is made of the ark of the covenant in the list of furnishings taken by the Babylonians to Babylon following the destruction in 586 BC (2 Kings 25:13–17; Jeremiah 52:17–23), most scholars presume the ark was destroyed by the Babylonians when they destroyed the temple. Scholars and others have suggested many speculative theories about the ark being lost, hidden, or taken away before its destruction. For example, an apocryphal book says that Jeremiah hid the ark in Mount Nebo (2 Maccabees 2:4–8). For a scholarly review of these theories, see John Day, “Whatever Happened to the Ark of the Covenant?,” in Temple and Worship in Biblical Israel, ed. John Day (New York: T&T Clark), 250–70.

[22] Philo, On the Special Laws 1.69. Quotations of Philo are taken from Philo, Loeb Classical Library, translated by F. H. Colson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1937–62).

[23] In the Synoptic Gospels the Last Supper is a Passover meal (Matthew 26:17; Mark 14:12; Luke 22:1–15); however, in John the Last Supper took place before Passover (13:1), and therefore Jesus may have been crucified on the day of Passover.

[24] For example, the emperor Caligula (AD 37–41) demanded his statue be erected and worshipped in the temple courtyards resulting in a widespread Jewish revolt. See the accounts in Philo, Embassy to Gaius 188, 198–348; Josephus, Antiquities 18.261–309; Jewish War 2.184–203).

[25] As quoted in Jonathan Klawans, Purity, Sacrifice, and the Temple: Symbolism and Supersessionism in the Study of Ancient Judaism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 205.

[26] For a complete discussion of the relationship between prayer, study, and acts of loving-kindness and temple sacrifice, see Klawans, Purity, Sacrifice, and the Temple, 203–11.

[27] For a report of the excavations of the alleged temple site on Mount Gerizim see Yitzhak Magen, “Bells, Pendants, Snakes and Stones,” Biblical Archaeology Review 36/

[28] Bertil Gärtner, The Temple and the Community in Qumran and the New Testament: A Comparative Study in the Temple Symbolism of the Qumran Texts and the New Testament, Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[29] Yigael Yadin, The Temple Scroll: The Hidden Law of the Dead Sea Sect (New York: Random House, 1985); Johann Maier, The Temple Scroll: An Introduction, Translation, and Commentary (London: Bloomsbury, 2009); Adolfo Roitman, Envisioning the Temple (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2003).

[30] For a comprehensive discussion of how Christians interpreted scripture in regard to the temple, see G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. New Studies in Biblical Theology (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004).

[31] Steven Fine, The Menorah from the Bible to Modern Israel (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 4.