Tyler J. Griffin, "Jerusalem, the Holy City: A Virtual Tour of the City in the New Testament Period," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 35-52.

Tyler J. Griffin is associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University (Provo).

“He who has not seen the Temple of Herod has never seen a beautiful building”[1]

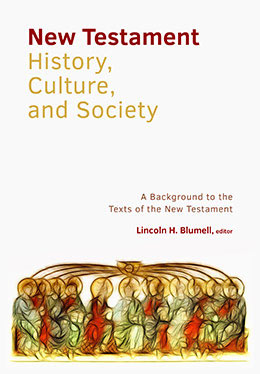

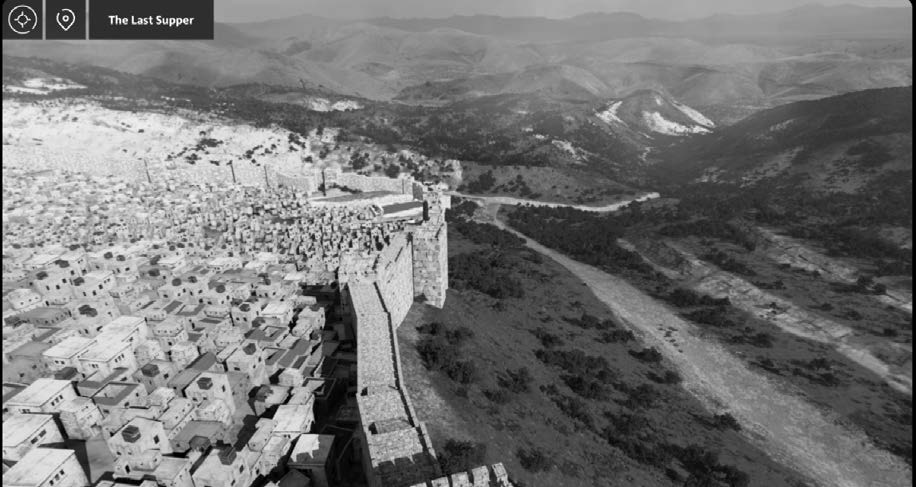

Figure 1. View of Temple Mount in Virtual New Testament App

Figure 1. View of Temple Mount in Virtual New Testament App

(facing west-southwest).

Few cities have attracted more attention, from more people, for a longer period of time than Jerusalem.[2] For Jews and Muslims, this city is esteemed as a promised land, filled with holy sites integrally important to their religions and identities as a people. On the same rock where Jewish tradition holds that Abraham nearly sacrificed his son, Isaac (the rock inside the Holy of Holies, where the ark of the covenant rested [Genesis 22]), Muhammad is believed to have ascended into heaven (al-Sakhra). For Christians, the central importance of Jerusalem is manifested by Jesus’s personal presence in the city. It was in and around Jerusalem that Jesus was presented in the temple as an infant, taught the learned men as a twelve-year-old, cleansed the temple, taught the people, healed the sick, suffered in Gethsemane, was condemned, suffered and died on the cross, then became the first to rise from the dead. Though two thousand years have passed since these events occurred, Christians continue to visit the city so they can walk in his footsteps. By combining the latest archeological and historical research with modern technology, we are now able to create a virtual reconstruction of the city and its environs as they possibly appeared at the time of Christ. This chapter offers readers a “virtual tour” of sorts as it attempts to peel away nearly two thousand years of geographic and structural changes now visible in the present city.

The Setting for the City

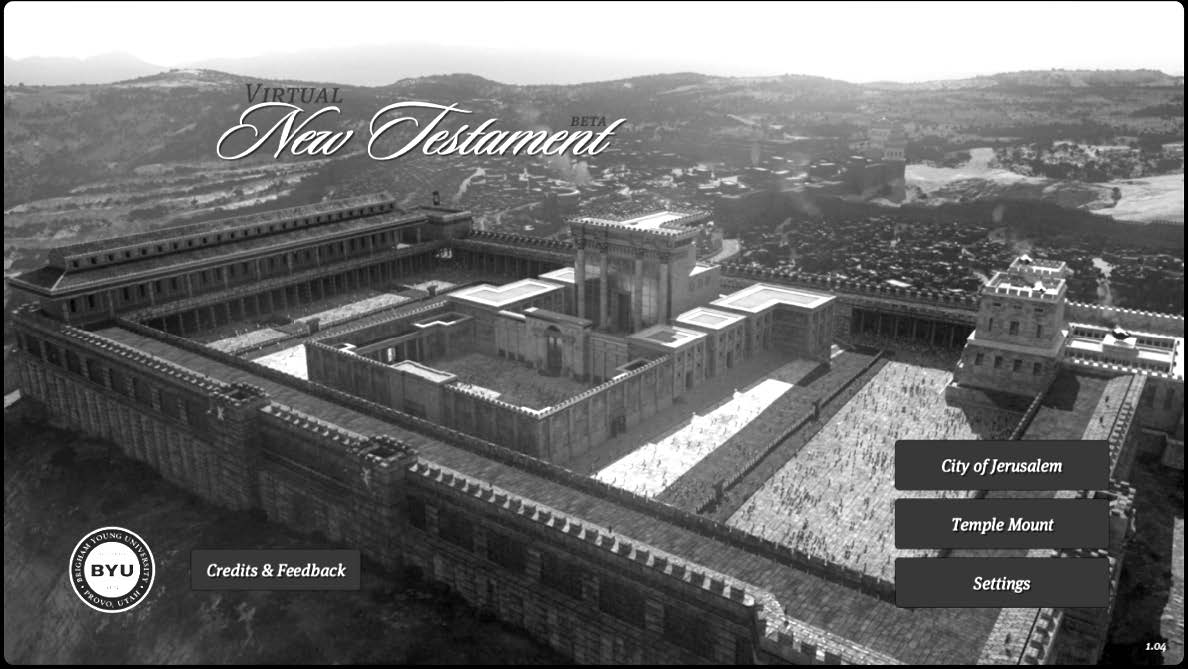

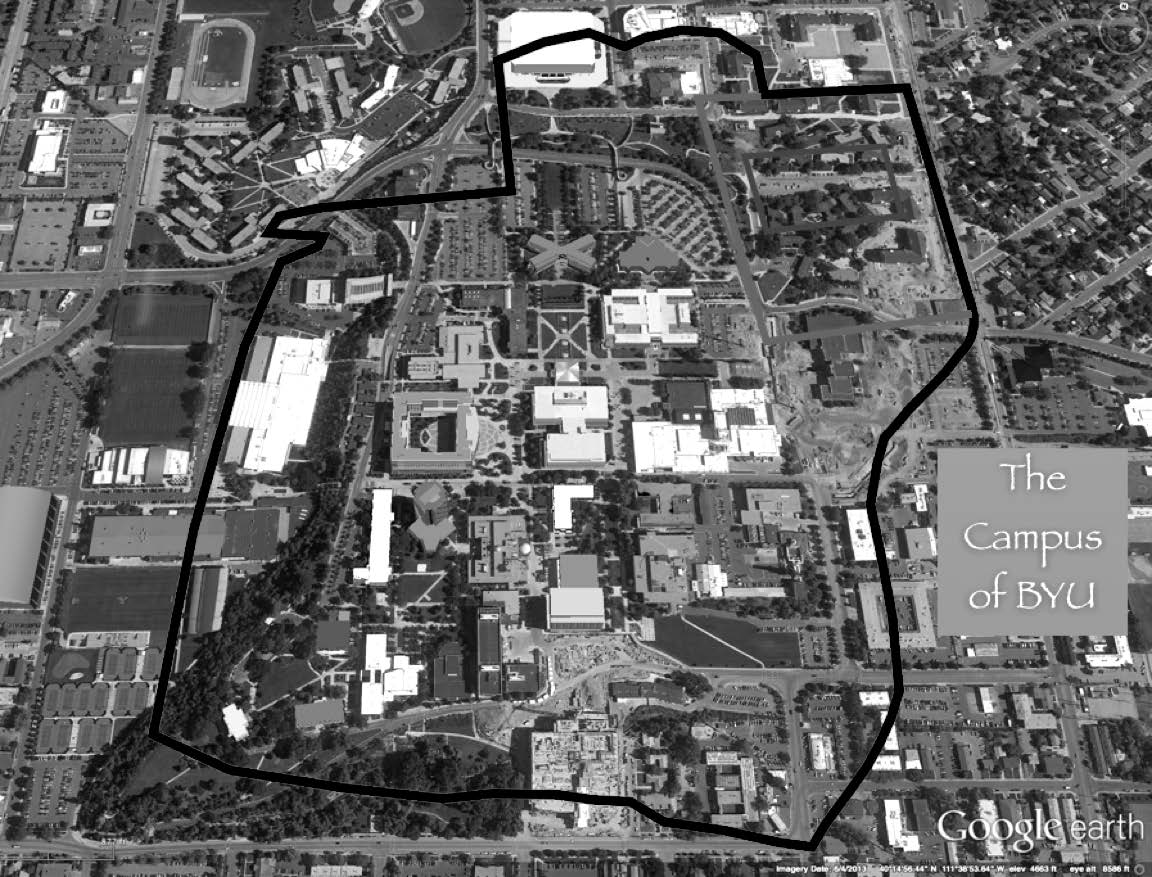

Figure 2. Elevations of the Holy Land.

Figure 2. Elevations of the Holy Land.

To begin, it is worthwhile to start with an overview of the geographical setting for Jerusalem and how that affected its inhabitants and visitors in the New Testament period. The city is located approximately 40 miles (65 km) east of the Mediterranean Sea and about 100 miles (160 km) south of the Sea of Galilee. In the New Testament, Jewish people traveled between Jerusalem and Galilee using one of two main routes, through Samaria or through the deep Jordan River valley.[3] The latter route took much longer and required a steep climb from Jericho (nearly 900 feet below sea level) through a dry and desolate wilderness, before arriving in Jerusalem (2,540 feet above sea level).

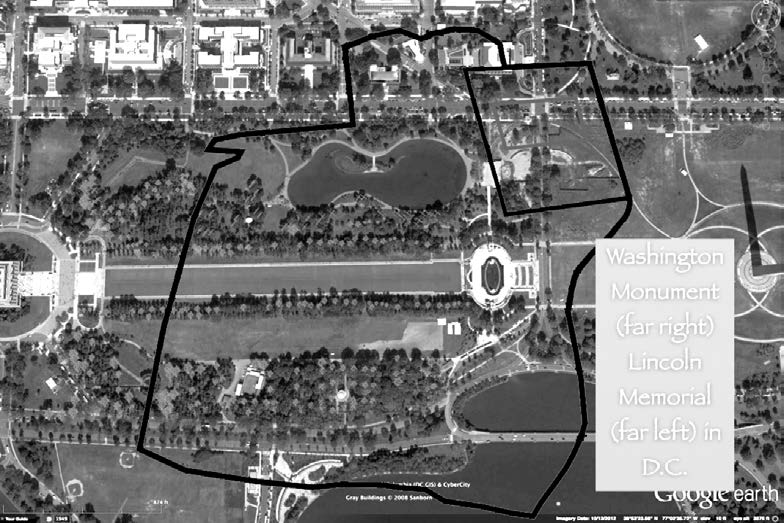

At the time of Jesus, the large city walls encircled an area just under one square mile in size. For perspective, compare the three Google Earth images above depicting a red outline of the old city walls superimposed over three locations of today, the campus of Brigham Young University (BYU), the area between the Lincoln and Washington Memorials in Washington D.C., and a portion of Central Park in New York City.

Figure 3. Comparison of relative size: ancient Jerusalem

Figure 3. Comparison of relative size: ancient Jerusalem

with three US locations today.

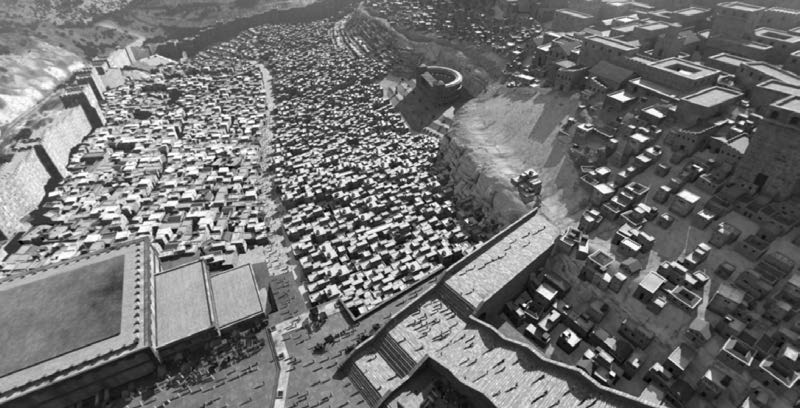

The city walls encircled two large hills, Mount Moriah (also known as Temple Mount) and Mount Zion, the higher hill to the southwest. These were separated by the Tyropoeon Valley (i.e., “valley of the cheesemakers”) running between them from north to south. Two steep valleys outside the walls, the Hinnom on the west and Kidron on the east, helped create a natural defense for the city. Jerusalem was nearly surrounded by taller hills and mountains around much of its perimeter, including the Mount of Olives directly to the east. The following image, taken from the BYU Jerusalem Center on Mt. Scopus (looking southwest) shows the golden Dome of the Rock situated on the summit of Mount Moriah.

Figure 4. View of the Dome of the Rock from Mt. Scopus.

Figure 4. View of the Dome of the Rock from Mt. Scopus.

Note how low the Dome of the Rock sits compared with the hills and mountains encircling most of the city. Psalm 125:2 describes this geographical setting for the Holy City, “As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about his people from henceforth even for ever.”

The main regions of the city mentioned in the New Testament are labeled and discussed as follows:

- Temple Mount

- Kidron Valley and the Mount of Olives

- The Lower City (City of David)

- The Upper City (Mount Zion)

- The northern quarries, gardens, and pools

The Temple Mount

Figure 5. Significant regions of Jerusalem.

Figure 5. Significant regions of Jerusalem.

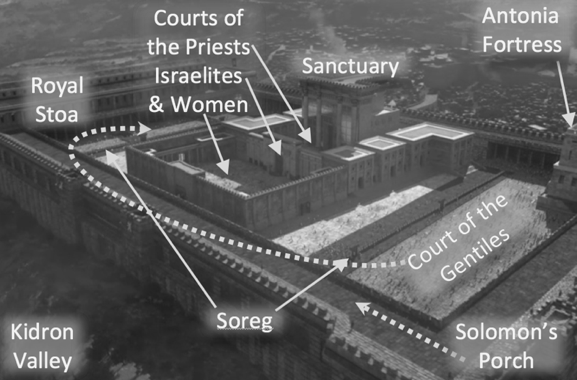

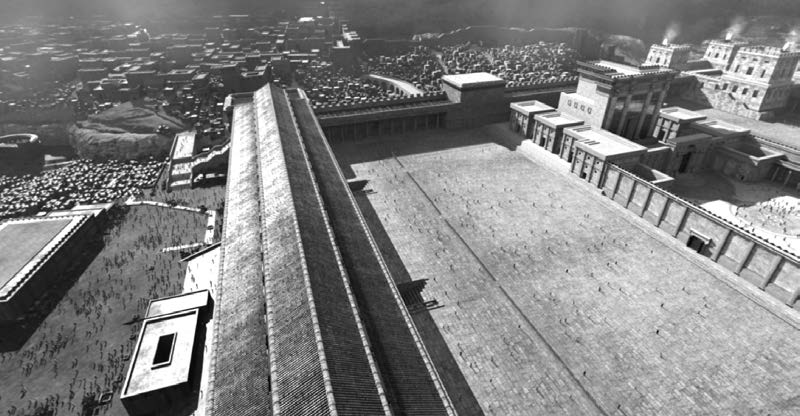

The temple dominated the city. Its trapezoid shape covered over 169,000 square yards (more than twenty-six American football fields).[4] The platform was covered by many structures and courtyards, including the sanctuary of the Holy Place and Holy of Holies, the Royal Stoa (a large portico structure covering the southern end of the platform), and the Antonia Fortress (in the northwest corner of the platform).

This image shows the southwest corner of the temple. The spacious plaza and monumental staircases leading up to the temple were big enough to accommodate the large numbers of pilgrims who would pour into the city during important festivals. The stair treads on the large staircases were built at inconsistent depths, perhaps to require visitors to the Temple Mount to ascend with greater care and reverence.[5] Geographically, this was the center of the city. Markets lined the plaza to the south and the busy street to the west of the temple. The Wailing Wall, or Western Wall, of the temple is located approximately 550 feet (165 meters) to the north of this southwest corner. Today, faithful Jewish worshippers congregate there to offer prayers because that is as close as they can get to the physical location of the ancient Holy of Holies.

Figure 6. View of Temple Mount, facing Southwest, with Mt. Zion in the background.

Figure 6. View of Temple Mount, facing Southwest, with Mt. Zion in the background.

People could enter the temple through various gates, including the double and triple gates on the south—Robinson’s Arch, Barclay’s Gate, Wilson’s Arch—and Warren’s Gate on the west. From atop the southwest pinnacle (upper-left corner of figure 7), a priest would sound a trumpet to signal important events such as the beginning and ending of the Sabbath, and daily sacrifices each morning and afternoon.[6] It was likely from that point or the southeast pinnacle (far right side of figure 7) where Jesus was tempted by Satan to cast himself down (Matthew 4:5–7).

Figure 7. Southern façade of the Temple with Large Plaza and

Figure 7. Southern façade of the Temple with Large Plaza and

Markets.

Everything on the Temple Mount was designed to symbolize approaching the presence of God, which emanated from within the Holy of Holies (the highest place on the mount). All non-Jews (Gentiles) were allowed to ascend onto the platform but were not allowed to pass through a three-cubit high stone fence of latticework, called the “Soreg.” This 500-cubit square border separated the outer porticoes from the inner courts.

A portion of this Soreg can be seen as a faint line between the Royal Stoa and the temple in figure 9. Openings in the Soreg were clearly marked with inscriptions in Greek and Latin warning all Gentiles that they would be responsible for their own deaths if they entered the gates (compare Acts 21:28–30).[7]

Figure 8. View from atop the place of the trumpeter on the southwest pinnacle (facing south), and a view

Figure 8. View from atop the place of the trumpeter on the southwest pinnacle (facing south), and a view

from above the southeast corner of the temple (facing west).

Consider the depictions of Jesus cleansing the temple in the context of the monumental size of the Temple Mount and the number of pilgrims that frequented Jerusalem during festivals such as Passover. It is hard to know exactly how many money changers and sellers of sacrificial animals were involved or where they were located on the mount when Jesus confronted them and expelled them.

Unlike the Gentiles, all Jews could pass through the Soreg, cross the large stone courtyard, and enter the large square enclosure called the Court of the Women depicted on the right in figure 9 and seen from the ground level in figure 11.

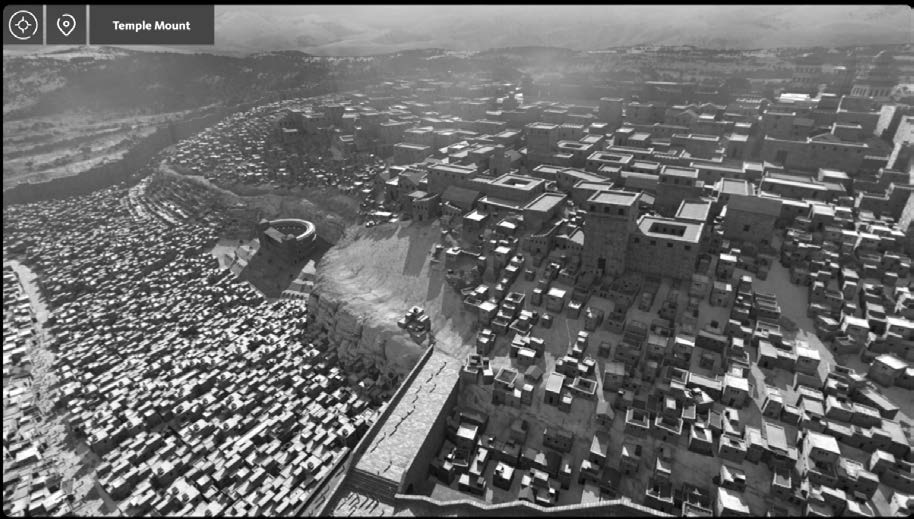

Figure 9. View of the Temple Mount from atop the

Figure 9. View of the Temple Mount from atop the

southeast end of the Royal Stoa (facing northwest).

Figure 11. Interior view of the Court of the Women

Figure 11. Interior view of the Court of the Women

(facing southwest).

Figure 10. The Soreg, or wall of partition, with inscriptions

Figure 10. The Soreg, or wall of partition, with inscriptions

warning the Gentiles not to pass through the

gates or they would be killed.

This court contained four large chambers in each of its corners, one for sorting wood to be used on the altar (northeast corner), one for those taking a Nazarite vow (southeast corner), one for oil and wine to be used in the temple (southwest corner), and one for lepers to wash themselves before being presented before the priests (northwest corner).[8] The Court of the Women also contained the treasury, which consisted of thirteen trumpet-shaped boxes for donations as depicted in the foreground of figure 11 (Mark 12:41–44).

The innermost part of this court contained fifteen semicircular steps leading up to the large Nicanor Gate.[9] Levites would stand on these steps, play their instruments, and sing psalms. The Nicanor Gate was located at the top of these steps. Only Jewish men were allowed to pass through the gate into the Court of the Israelites, but they were not allowed to proceed beyond the one-cubit-high step into the Court of the Priests.

Figure 12. Nicanor Gate and 15 semi-circular steps on the west end of the Court of the Women.

Figure 12. Nicanor Gate and 15 semi-circular steps on the west end of the Court of the Women.

Figure 13. The inner side of the Nicanor Gate with

Figure 13. The inner side of the Nicanor Gate with

the Court of the Israelites separated from the Court

of the Priests by a one-cubit-tall step.

Figure 14. The Court of the Priests (facing southwest)

Figure 14. The Court of the Priests (facing southwest)

with the altar on the left and the sacrificial

area on the right.

There were twenty-four distinct groups of priests who would officiate at the temple for one week at a time, thus assuring that the special occasions (e.g., Passover, Pentecost, Tabernacles, Hanukkah, etc.; see Luke 1:5–9) would systematically rotate through each of the groups from year to year.[10]

Sacrificial animals were killed in the area north of the altar (Leviticus 1:11). Because of the large number of animals slain in the temple, especially during one of the annual feasts, a steady supply of water was required for the priests to wash themselves and keep their courtyard clean. A continuous flow of fresh water was piped in from Solomon’s Pools, located south of Bethlehem.[11] The priestly courtyard was built in such a way that water could be flooded over the stones and then collected into an underground drainage system that channeled the sacrificial fluids and waste down into the Kidron Brook, which eventually emptied into the Dead Sea.

A series of steps led from this courtyard up to a porch on the eastern face of the Sanctuary. This porch contained a giant vine with grapes and leaves made out of pure gold. The wooden door into the Sanctuary was covered with a colorful outer veil that could be pulled aside. The Holy Place contained three sacred furnishings, the candelabra (or menorah), the altar of incense, and the table of shewbread (Hebrews 9:2). A large veil hung from floor to ceiling and wall to wall, separating the Holy Place from the Holy of Holies. Only the high priest could pass through the veil, one time each year, on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur; Hebrews 9:7). He would sprinkle blood on the rock escarpment where the ark of the covenant had been placed during Solomon’s time. At Jesus’s crucifixion, this veil was ripped from top to bottom (Mark 15:38; Matthew 27:5; Luke 23:45), symbolically signifying that he was the High Priest who would be going into the presence of God and opening the gate of heaven for all who would choose to enter as well (Hebrews 9–10).

Figure 15. View of the Antonia Fortress from the Court of

Figure 15. View of the Antonia Fortress from the Court of

the Gentiles (on the left) and view looking down into the

courtyards from the steps of the Antonia.

The Antonia Fortress was a large structure built in the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. It was built as a northern fortress for the city and Temple Mount. It also housed the Roman garrison in charge of keeping the peace in the temple. Roman soldiers pulled Paul away from an angry crowd in the Court of the Gentiles and brought him here, to the “castle” (Acts 21:30–37), where from the stairs he addressed the crowd below.

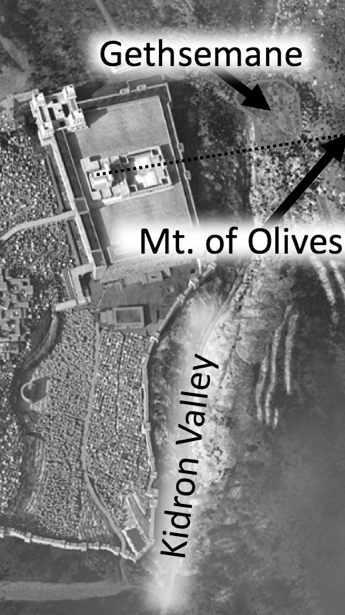

Kidron Valley and the Mount of Olives

Jesus’s triumphal entry began in the region of Bethany and Bethphage, just over the Mount of Olives to the east of Jerusalem. He ascended the mount and then descended into the steep Kidron Valley before riding triumphantly into Jerusalem (Matthew 21:6–11; Mark 11:7–11; Luke 19:35–38; John 12:12–18).

This mountain forms part of the border between the fruitful plains and hill country to the west and the desolate Judean wilderness that slopes sharply down toward Jericho, the Jordan River valley, and Dead Sea to the east. Jesus often resorted to the Mount of Olives (John 18:2; Luke 22:39).

Figure 16. East of Jerusalem.

Figure 16. East of Jerusalem.

The temple was aligned in such

a way that it formed a straight

line with the summit of the

Mount of Olives.

Figure 17. View of the southern portion of the Kidron Valley with tombs carved into the limestone face of the Mount of Olives, facing Southeast.

Figure 17. View of the southern portion of the Kidron Valley with tombs carved into the limestone face of the Mount of Olives, facing Southeast.

Figure 18. View of Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives (facing

Figure 18. View of Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives (facing

West), just before sunset.

From here, he delivered the famous Olivet Discourse to his disciples (Matthew 24 and Joseph Smith—Matthew), wherein he foretold of the complete destruction of the temple and revealed many things that would occur at the hands of the Romans (AD 70) and many signs that would be shown before his Second Coming. It was also from this mountain that Luke tells us that Jesus ascended to heaven following his forty-day, post-Resurrection ministry (Acts 1:1–11).

Figure 19. View of the temple’s eastern gate (the Golden Gate) from the Kidron, just outside Gethsemane

Figure 19. View of the temple’s eastern gate (the Golden Gate) from the Kidron, just outside Gethsemane

looking up the hill toward the west. The tip of the Dome of the Rock can be seen in the center of the photo.

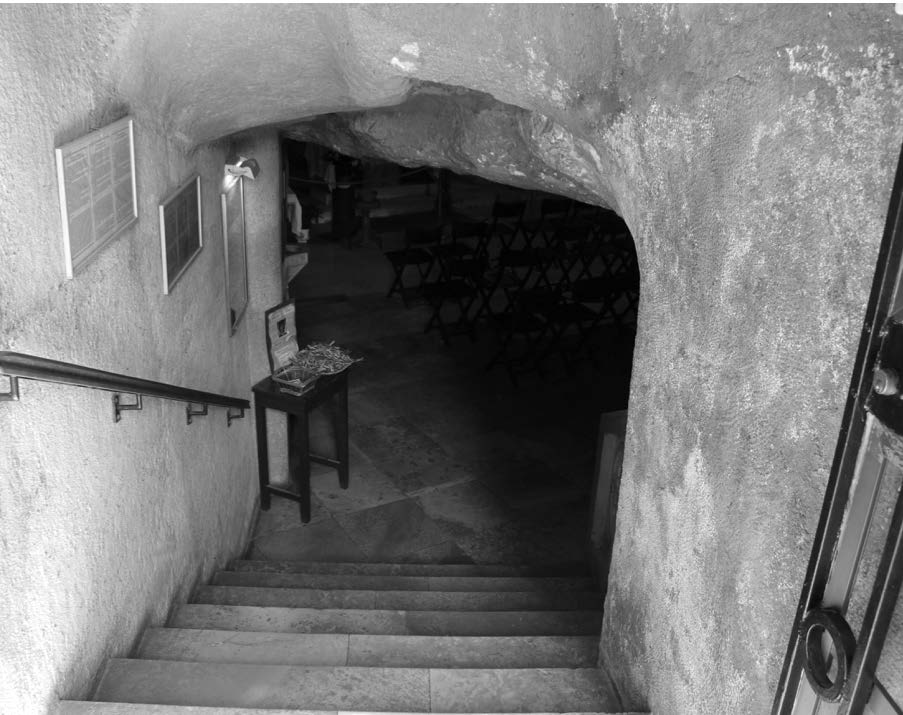

Near the northern end of the Kidron Valley, at the base of the Mount of Olives, was a grove of olive trees and a working olive press (called a gethsemane) located inside a cave. The night before Jesus’s crucifixion, after the Last Supper with his apostles, he invited them to leave the Upper Room with him (John 14:31). Jesus continued to teach them as they made their way up the Kidron Valley (John 15–16). Right before entering Gethsemane, he paused to offer his Intercessory Prayer (John 17).

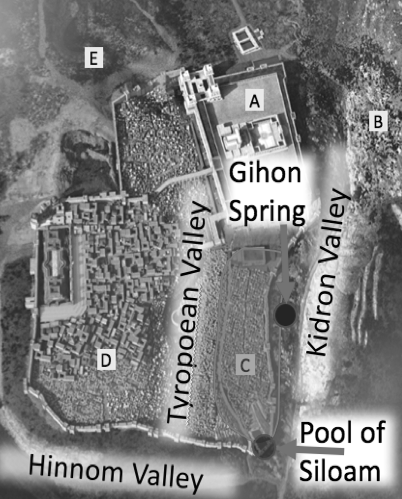

The Lower City (City of David)

In earlier Old Testament times, Jerusalem was limited to the region known as the Lower City (the region shaded in red in figure 22). As time passed, various kings and leaders kept expanding the reach of the city to the north and the west. The Gihon Spring was the only source of fresh water in the city during biblical times. In the time of Isaiah, Hezekiah built a tunnel through solid rock, connecting the fresh water from this spring to the Pool of Siloam, which sits at the lowest point of elevation in the city, near the main southern entrance into the city.

Figure 20. Olive trees in Gethsemane today.

Figure 20. Olive trees in Gethsemane today.

Right before his death, King David directed his son Solomon to be placed on David’s mule and taken to the Gihon Spring. There, he was anointed king of Israel before riding triumphantly into the city to sit upon his father’s throne (1 Kings 1:32–35). Centuries after this event, Jesus was seen riding into Jerusalem, on “the foal of an ass,” amid shouts of hosanna from the Kidron Valley, and the leaders of the Jews did not miss the significance of the symbolism (Mark 11:7–10; Matthew 21:9–11; John 12:12–19).[12] They demanded that Jesus stop the crowds from declaring him the son of David, heir to his throne (Matthew 21:15–16; Luke 19:39–40).

Another feature of the Kidron Valley was an extensive garbage dump dating to the first century.[13] The odors from this giant refuse pile, combined with the animal waste tainting the Kidron Brook (by-products of temple sacrifices) would have made this lower part of the Kidron Valley very unpleasant, especially at Passover when so many lambs were being killed and bled out in the temple.

Figure 21. Modern entrance into the cave that housed

Figure 21. Modern entrance into the cave that housed

the oil press (Gethsemane) in Jesus’s day.

Figure 22. The Lower City, or City of David.

Figure 22. The Lower City, or City of David.

Figure 23. The pool of Siloam, a large public pool for ritual washing (mikvah). Fresh water could also be

Figure 23. The pool of Siloam, a large public pool for ritual washing (mikvah). Fresh water could also be

gathered from a small feeder pool on the left.

Another story involving this part of the city took place in John 9. On that Sabbath day, Jesus left the temple and encountered a blind man. Jesus made spittle clay, anointed the man’s eyes, and commanded him to go wash in the Pool of Siloam. There were many other sources of water situated much closer to the temple, but Jesus required the blind man to walk a great distance, down a steep path with many steps, on the Sabbath day in order to reach Siloam and wash.

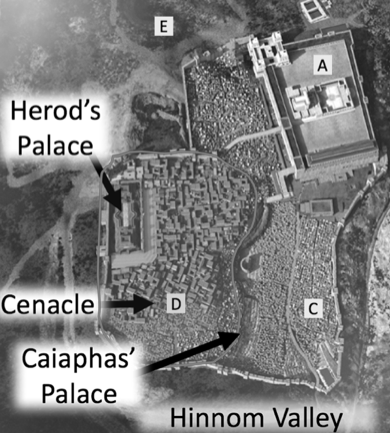

The Upper City (Mount Zion or the Western Hill)

Figure 24. View of the Upper City (facing west) from the pool of Siloam.

Figure 24. View of the Upper City (facing west) from the pool of Siloam.

The Upper City is so designated because of its higher elevation in relation to the other parts of the city. This was where Jerusalem’s elite built their homes, most of which were opulent in comparison with the poorer class of dwellings in the Lower City. Visitors to Jerusalem today can see a few homes and structures that date back to the time of Christ, including the Palatial Mansion and the Burnt House of the Katros family.[14]

Herod built a large palace on the highest point of the Western Hill, such that he could look down into the temple courtyards to the east. Within these fortified walls, he built two castle-like palaces, each with its own lavish accommodations for hundreds of guests. The walls also encompassed extensive water features, gardens, vineyards, extravagant furnishings, and a large barracks for soldiers assigned to protect the palace.[15]

Figure 25. The Upper City, Mount Zion, or the

Figure 25. The Upper City, Mount Zion, or the

Western Hill.

Figure 26. View from the southwest corner of the city looking north. Mount Zion is on the left with Herod’s Palace. Mount Moriah is on the right.

Figure 26. View from the southwest corner of the city looking north. Mount Zion is on the left with Herod’s Palace. Mount Moriah is on the right.

For added fortification, he built three towers on the northern end of the palace (these can be seen in figure 26 as the highest altitude features in the city). Herod named the towers Phasael (after his brother), Hippicus (after a friend), and Mariamne (after one of his wives).

The Cenacle, or traditional Upper Room site, would be located near the bottom left corner of figure 27. The current Cenacle was not constructed until the twelfth century, but it is possibly built over the ruins of the original site where Jesus shared his Last Supper with the apostles, washed their feet, and introduced the sacrament. Other possibilities for the location of the Upper Room include other parts of the Upper City, or any large, open room on a top floor of one of the many structures built in step-wise fashion into the steep hillside that separates the Lower City from the Upper City (as depicted running down the middle of figure 28). The traditional site, Akeldama, where Judas Iscariot was buried after hanging himself (Matthew 27:8; Acts 1:19), would be located in the far righthand side of figure 27 in the Hinnom Valley.

Figure 27. View of the southern part of the Upper City in the

Figure 27. View of the southern part of the Upper City in the

foreground and the Lower City in the background with the

Hinnom Valley on the right.

Figure 28. View of the Upper City on the right with the priestly

Figure 28. View of the Upper City on the right with the priestly

mansions in the foreground and Herod’s Palace in the background.

The Lower City is shown on the left.

St. Peter in Gallicantu (i.e., “cock’s crow”) is the traditional site of Caiaphas’s Palace, where Jesus was taken following his arrest in Gethsemane to be judged of the leaders of the Jews: Caiaphas (the high priest), Annas (Caiaphas’s father-in-law), and the Sanhedrin (the authoritative body of Jewish leaders). This palace would have been located near the southern edge of the steep hill separating the Upper from the Lower City (near the middle of figure 27).

On Jesus’s final night he left the Upper Room, likely from one of the southern parts of the city, walked up the Kidron Valley, endured the agonies of Gethsemane, and was taken back down the valley, into the city, and up the hill to Caiaphas’s Palace. After being condemned by the Sanhedrin, he was taken to be judged by Pilate. Even though long-standing tradition places the judgment and scourging experiences in the Antonia Fortress, it would have been more likely for Pilate to have been staying in the more luxurious accommodations of Herod’s palace at the time. Pilate sent Jesus to be judged by Herod Antipas (Herod the Great’s son, the Roman-appointed ruler in Galilee and Perea who was in Jerusalem at the time; Luke 23:7–12). Herod sent him back to Pilate, where he was ultimately condemned, scourged, and sent away to be crucified.

The Northern Quarries, Gardens, and Pools

The Pool of Bethesda is the site of the miracle recorded in John 5. It is described as a pool near the sheep market with five porches. After many centuries of confusion over the meaning of this description, two large pools were discovered north of the Temple Mount in a region known as Bezetha.[16] The five porches refer to the covered porticoes surrounding the four sides of the pools, plus one dividing them down the middle. The northern pool was a large collecting pool for fresh water. The southern pool was a large mikvah (ritual bath) for Jewish purity rituals. A sluice gate could be opened between the two pools, and water would rush down into the southern pool from the fresh water supply of the higher northern pool.

This part of Jerusalem was known as a gathering place for many who were sick and infirm. During the time of Christ, or shortly thereafter, a Greco-Roman healing center was built in this same area. These ancient hospitals were called asclepeions, being named after the Greek god of healing and well-being, Asclepius. In the King James Version of the Bible, John 5:4 states that “an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water; whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had.” This verse, however, is absent from all early manuscripts of the New Testament. It was added much later, perhaps to explain the lame man’s frustration at having “no man, when the water is troubled, to put me into the pool” (John 5:7).

Figure 29. The northern regions of Jerusalem

Figure 29. The northern regions of Jerusalem

Figure 30. The dividing walkway between the

Figure 30. The dividing walkway between the

north and south pools.

Figure 31. View looking down at the first-century

Figure 31. View looking down at the first-century

mikvah.

Because of heavy public usage of a large mikvah (like this one and the Pool of Siloam), the water would likely have become extremely dirty and contaminated. When an infusion of fresh water was introduced into the pool through the sluice gate, the sick folk would rush to be the first one into the pool, believing they would be healed. Jesus bypassed all the traditions of the day and simply commanded the man to take up his bed and walk, even though it was the Sabbath day (John 5:8–9). This event led to Jesus’s first major confrontation in the Gospel of John with the leaders of the Jews in the temple later that day (John 5:10–47).

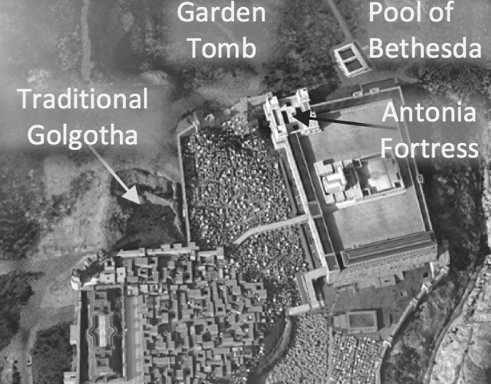

There has been much debate over the location of Calvary, or the “place of the skull,” where Jesus was crucified, buried, and then resurrected (Mark 15:22; Matthew 27:33; and John 19:17). The majority of the Christian world views the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the site for Golgotha. The traditions for this location date back many centuries. Helena, Emperor Constantine’s mother, paid for a church to be constructed over the site in the early fourth century.

Since 1867, however, many Protestants and other Christian groups believe that Gordon’s Calvary, or the Garden Tomb, is where these events took place. One argument advanced for this site is the skull-like rock near the actual tomb.

Figure 32. A skull-like image in the rock near the Garden

Figure 32. A skull-like image in the rock near the Garden

Tomb.

Interpretation of the “skull” passages could also simply mean a place where death occurred and not be dependent on a physical characteristic of the surrounding land. Both locations would have been outside the walls of the city in that day (John 19:20). Both would have been near a road into the city. Both locations also had gardens nearby: “Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden; and in the garden a new sepulcher, wherein was never man yet laid” (John 19:41; see also Matthew 27:60). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was an active quarry in the first century, whereas the Garden Tomb, based on its style and design, seems to have been carved hundreds of years before the time of Christ. There could have been other tombs in the vicinity of the Garden Tomb, however, that were newly carved by Joseph of Arimathea. The critical point is not exactly where these events happened, but that somewhere in this region, Jesus Christ was crucified on a cross, laid in a tomb, and rose triumphant over the grave three days later.

Conclusion

While it is not essential for a disciple of Christ to physically travel to the Holy Land to gain a testimony of the divinity of his life and mission, a better understanding of the setting where those events unfolded adds a richness and new dimension to one’s faith in Christ. Since travel to Israel is not feasible for most Christians in the world today, digital reconstructions of the city allow everyone to visually and virtually immerse themselves in the world of Jesus and his disciples. These experiences allow a student of the scriptures to better understand what they are reading as they gain a perspective in scope and scale of the places where these events took place.

Further Reading

Bahat, Dan. The Carta Jerusalem Atlas. Jerusalem: Carta, 2011.

Galbraith, David, D. Kelly Ogden, and Andrew C. Skinner. Jerusalem: The Eternal City. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996.

Ogden, D. Kelly. Biblical and Modern Geography of the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, 1985.

Richman, Chaim. The Holy Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Temple Institute, 1997.

Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, The Lamb Foundation, 2006.

Ritmeyer, Leen, and Kathleen Kitmeter. The Ritual of the Temple in the Time of Christ. Jerusalem: Carta, 2002.

Ritmeyer, Leen, and Kathleen Ritmeter. Secrets of Jerusalem's Temple Mount. Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1998.

Shanks, Hershel. Jerusalem's Temple Mount: From Solomon to the Golden Dome. New York: Continuum, 2007.

Notes

[1] Babylonian Talmud, Baba Bathra 4a.

[2] For a brief discussion of the significance of Jerusalem, and more importantly, the Temple Mount, see Hershel Shanks, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount: From Solomon to the Golden Dome (New York: Continuum International, 2007), 1–7.

[3] There is a long-standing tradition that Jews would rarely or never pass through Samaria. More recent scholarship calls that tradition into question. Jesus himself passed through Samaria in John 4, Luke 9:51–56, and 17:11. Other Jews in the New Testament also pass through Samaria in Acts 8:5, 14–15, 25, 26; and 15:3. Additionally, Josephus, the ancient Jewish historian clearly stated, “It was the custom of the Galileans, when they came to the holy city [Jerusalem] at the time of the festivals, to take their journeys through the country of the Samaritans” (Antiquities 20.118, emphasis added).

[4] See quick statistics on the Herodian Temple Mount Walls in Leen Ritmeyer, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 20. The surface area of the Temple Mount is 1,520,638.2 square feet, or 168,959.8 square yards. For comparison, a US football field is 360 feet long (including the endzones) and 160 feet wide for a total of 6,400 square yards. On the ancient Temple Mount, 26.4 football fields could fit (168,959.8 / 6,400).

[5] See Shanks, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, 79, “The alternating depths of the stair treads forced pilgrims to slow their pace while approaching the holy area.” See also Leen Ritmeyer, The Quest, 65, “The thirty steps, partly cut into the rock and partly built of large stones, were laid alternately as steps and landings, thus conforming to the slope of the mountain and assuring a reverent ascent.”

[6] For more details on the trumpeting stone, see Ritmeyer, Quest, 57–60.

[7] See Ritmeyer, Quest, 346–47.

[8] See Ritmeyer, Quest, 352–54.

[9] See Ritmeyer, Quest, 354–56.

[10] See Chaim Richman, The Holy Temple of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: The Temple Institute and Carta, 1997), 20.

[11] See Ritmeyer, Quest, 62.

[12] The triumphal entry was a common event in Jewish (and Roman) culture when a king returned from battle to show that he was victorious over the enemy. See Joshua 6; 1 Samuel 18:6–7; 2 Samuel 6:1–5, 12–17; 1 Kings 1:32–40; 8:1–61; Nehemiah 12:31–43; Esther 6:7–12; Psalm 68:24–27; Zechariah 9:9. See also Josephus, Jewish War 7.123–57; Plutarch, Aemilius 33–35; Dio Cassius 63.4.1–5.2. See further T. E. Schmidt, “Mark 15.16–32: The Crucifixion Narrative and the Roman Triumphal Procession,” New Testament Studies 41, no. 1 (January 1995): 1–18; and H. S. Versnel, Triumphus (Leiden: Brill, 1970).

[13] See the discussion regarding the recent findings of the ancient garbage dump in the Kidron Valley here. https://

[14] See https://

[15] Josephus’s description of Herod’s Palace: “[The King’s palace] was completely enclosed within a wall 30 cubits high, broken at equal distances by ornamental towers, and contained immense banqueting-halls and bedchambers for a hundred guests. The interior fittings are indescribable—the variety of the stones (for species rare in every other country were here collected in abundance), ceilings wonderful both for the length of the beams and the splendor of their surface decoration, the host of apartments with their infinite varieties of design, all amply furnished, while most of the objects in each of them were of silver or gold. All around were many circular cloisters, leading one into another, the columns in each being different, and their open courts all of a greensward; there were groves of various trees intersected by long walks, which were bordered by deep canals, and ponds everywhere studded with bronze figures through which the water was discharged and around the streams were numerous cots for tame pigeons” (Jewish War 5.176–81 Loeb).

[16] See https://

All of the 3D images included in this chapter are screenshots from an app called Virtual New Testament. Visit virtualscriptures.org to download the app for Mac or PC. Search for “Virtual New Testament” in the Apple or Google Play stores to download the app to your smart phone or smart device (Android devices and iPhones/

Further Readings

If you are interested in studying more about the ancient city of Jerusalem, see the following books:

Bahat, Dan. The Carta Jerusalem Atlas. Jerusalem: Carta, 2011.

Galbraith, David, D. Kelly Ogden, and Andrew Skinner. Jerusalem: The Eternal City. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996.

Ogden, D. Kelly. Biblical and Modern Geography of the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Center for Near Easter Studies, 1985.

Richman, Chaim. The Holy Temple of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Temple Institute, 1997.

Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, The Lamb Foundation, 2006.

Ritmeyer, Leen, and Kathleen. The Ritual of the Temple in the Time of Christ. Jerusalem: Carta, 2002.

Ritmeyer, Leen, and Kathleen. Secrets of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1998.

Shanks, Hershel. Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, From Solomon to the Golden Dome. New York: Continuum, 2007.