The King James Translation of the New Testament

Lincoln H. Blumell and Jan J. Martin

Lincoln H. Blumell and Jan J. Martin, "The King James Translation of the New Testament," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 672-690.

Lincoln H. Blumell is an associate professor in the Department of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University.

Jan J. Martin is an assistant professor in the Department of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University.

The King James Version of the Bible (hereafter KJV) is arguably the most celebrated book in the English-speaking world. It has had an enormous impact on the English language and has done more to fix particular expressions in the minds of English speakers than any other book.[1] Though it was first published over four hundred years ago (1611), the KJV is still in print today and in spite of its archaic language and text-critical shortcomings, the KJV remains the Bible that more Americans choose to read than any other English translation.[2] The perpetual attraction of the KJV appears to be its language, which is at once ordinary and elevated, allowing it to ring in the ears and linger in the mind of its readers.

For English-speaking members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the KJV is a familiar friend. The Church has used the KJV since the days of Joseph Smith. However, it was not until the 1970s that a practical need for a Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV became apparent, and it wasn’t until 1979 that a Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV was published.[3] Surprisingly, even with the availability and use of the Latter-day Saint edition, it was not until May 1992 that the KJV was officially declared to be the Bible for English speakers.[4] The Handbook of Instructions (2010) now declares, “English-speaking members should use the Latter-day Saint edition of the King James Version of the Bible. . . . Although other versions of the Bible may be easier to read, in doctrinal matters, latter-day revelation supports the King James Version in preference to other English translations.”[5] This statement clearly explains the reason the Church continues to use the KJV when many other Christian churches have abandoned it for modern translations. It also frankly acknowledges that the King James Bible’s sixteenth-century language may present difficulties for the modern reader.

There are essentially two fundamental challenges with the English of the KJV: accessibility and accuracy. An accessible text uses language that its readers easily understand. Unfortunately, the sixteenth-century English of the KJV can make comprehension difficult in places. An accurate translation of a text uses a second language to carefully represent the original language as closely as possible. Since the publication of the KJV in 1611, there have been important advances in understanding biblical Hebrew and Greek and numerous discoveries of additional biblical manuscripts that have provided important textual variations and clarifications (see chapter 37). Unfortunately, the KJV text does not reflect these advances and in places it is simply an inaccurate translation.

This chapter, therefore, will address the accessibility and accuracy of the King James English, particularly in the New Testament. First, it will begin with a brief history of the translation of the KJV, illustrating the book’s textual ancestry. Second, it will demonstrate the composite nature of the KJV text by tracing the origins of each part of one New Testament passage. Third, it will illustrate why the KJV translators chose a heightened form of English by comparing a passage from the KJV New Testament with the same one taken from three other modern translations. Fourth, it will demonstrate challenges with accessibility using two examples of archaic words that are present in both the Old and New Testaments. Finally, the last part of this essay will include a section, in tabular form, of fifty passages in the KJV New Testament that are translated incorrectly and will provide a more accurate rendering of these passages so that readers of the KJV will be better able to navigate their way through its New Testament translation.

Translating the King James Bible

In January 1604, King James VI and I, king of Scotland, England, and Ireland, gathered religious leaders to Hampton Court in an attempt to establish religious uniformity throughout his kingdoms.[6] In the midst of the debates, James unexpectedly ordered the making of a new translation of the Bible. At the time of the conference, England was in the uncomfortable position of using two different Bibles: the Bishops’ Bible (1568) and the Geneva Bible (1560). The Bishops’ Bible, published by a group of English Bishops under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth I, was at the time the only one authorized for use in the church. Unfortunately, the bishops who produced the Bishops’ Bible were somewhat deficient in Hebrew and Greek scholarship and wrote in awkward, Latinate English. Consequently, the Bishops’ Bible never became popular, and lay people did not use it for study at home. The Geneva Bible, on the other hand, was published by a group of Protestant scholars living in exile during the reign of Mary I (1553–58). This translation had considerably more scholarly merit, and it also contained tables, marginalia, concordances, and a plethora of study aids for the benefit of the lay readership. It was an extremely successful English Bible and became the most popular version for private use, but King James refused to accept it as the Bible for the Church of England because he particularly disliked the antimonarchist sentiments in the book’s annotations.

King James’s solution to the religious divisions among his subjects was to make a uniform translation of the English Bible. Following a meeting at Hampton Court, where the king announced his intentions, efforts immediately turned to gathering a body of scholars who could provide the translation. By June 30, 1604, forty-seven of an intended fifty-four translators were appointed and were drawn from the ranks of England’s foremost scholars. They were divided into six committees called “companies”: two from Cambridge, two from Oxford, and two from Westminster, with each company assigned to translate a different section of the Bible. Under the direction of King James, fourteen rules were put in place to guide the companies as they carried out their translations. Because these guidelines were so central to the translation, they are listed here in their entirety:[7]

- The ordinary Bible read in the Church, commonly called the Bishops’ Bible, to be followed, and as little altered as the truth of the original will permit.

- The names of the prophets, and the holy writers, with the other names in the text, to be retained, as near as may be, accordingly as they are vulgarly used.

- The old ecclesiastical words to be kept, viz.: as the word “Church” not to be translated “Congregation” etc.

- When a word hath diverse significations, that to be kept which hath been most commonly used by the most of the Ancient Fathers, being agreeable to the propriety of the place, and the Analogy of Faith.

- The division of the chapters to be altered either not at all, or as little as may be, if necessity so require.

- No marginal notes at all to be affixed, but only for the explanation of the Hebrew or Greek words, which cannot without some circumlocution so briefly and fitly be expressed in the text.

- Such quotations of places to be marginally set down as shall serve for fit reference of one Scripture to another.

- Every particular man of each company to take the same chapter or chapters, and having translated or amended them severally by himself where he think good, all to meet together, confer what they have done, and agree for their parts what shall stand.

- As one company hath dispatched any one book in this manner, they shall send it to the rest to be considered of seriously and judiciously, for His Majesty is very careful for this point.

- If any company, upon the review of the book so sent, shall doubt or differ upon any place, to send them word thereof, note the place and withal send their reasons, to which if they consent not, the difference to be compounded at the general meeting, which is to be of the chief persons of each company, at the end of the work.

- When any place of especial obscurity is doubted of, letters to be directed by authority to send to any learned man in the land for his judgement of such a place.

- Letters to be sent from every Bishop to the rest of his clergy, admonishing them of this translation in hand, and to move and charge as many as being skilful in the tongues have taken pains in that kind, to send his particular observations to the company, either at Westminster, Cambridge or Oxford.

- The directors in each company to be the Deans of Westminster and Chester for that place, and the King’s Professors in the Hebrew and Greek in each University.

- These translations to be used where they agree better with the text than the Bishops’ Bible, viz.: Tyndale’s, Matthew’s, Coverdale’s, Whitchurch’s [Great Bible], Geneva.

[15.] Besides the said directors before mentioned, three or four of the most ancient and grave divines, in either of the universities not employed in the translating, to be assigned by the Vice-Chancellors, upon conference with the rest of the heads, to be overseers of the translations as well Hebrew as Greek, for the better observation of the 4th rule above specified.[8]

To facilitate the translation process, and in accordance with instruction number 1, forty folio-sized unbound 1602 Bishops’ Bibles were distributed to the translators to work from. By design, the new Bible was a revision of previous Bibles rather than a new translation. The Bishops’ Bible was the core text. Working from it, the translators examined the other Bibles, particularly the Hebrew and Greek originals for the Old and New Testament respectively, and selected what they felt were the right words for every verse. Even though only a few of the translators’ papers have survived, they still provide invaluable insights into the process of translation.[9]

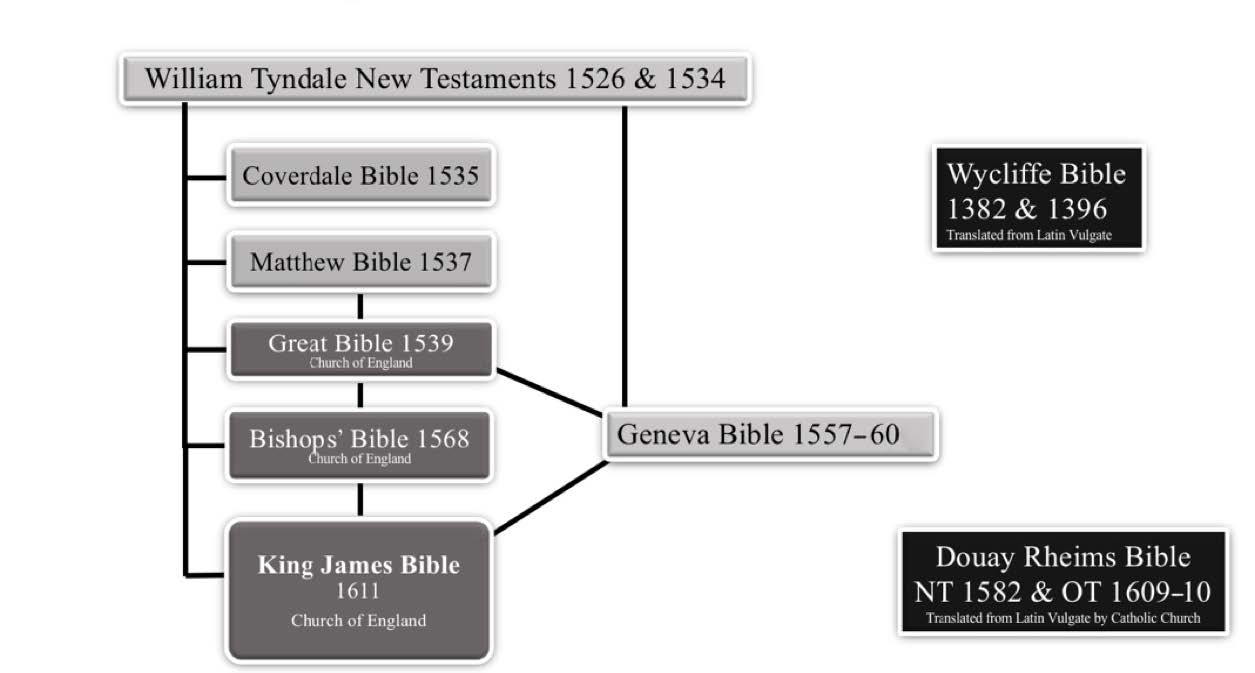

Table 1. King James Bible predecessors.

Table 1. King James Bible predecessors.

Today, this kind of approach to Bible translation is typical, but in the early 1600s, this scheme was incredibly innovative. Because the KJV is effectively a revision of the Bishops’ Bible, which is itself a revision of earlier English Bibles, the KJV is not the fixed and stable work of one collection of translators. Thus, its reputation as the hallmark of all English Bibles is misleading. As the KJV translators themselves explained, “wee never thought from the beginning, that we should neede to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one . . . but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principall good one.”[10] The “good one” that they were going to improve was the Bishops’ Bible of 1568. The “many good ones” were the Bibles made by a handful of predecessors. Thus, the KJV has a textual ancestry.

Even though the followers of the Oxford theologian John Wycliffe (1320–84) translated the Latin Vulgate Bible into an excessively literal Middle English in the late fourteenth century, William Tyndale (1494–1536) is the true father of the English Bible. Tyndale, an exiled, reform-minded English priest with an extraordinary gift for languages, was the first person to translate the New Testament into English from Greek source texts (1526). Likewise, he was also the first person to translate portions of the Old Testament into English from the Hebrew source text. He completed the Pentateuch in 1530 and Jonah in 1533. Joshua–2 Chronicles was published posthumously in 1537.[11] Because of his arrest in Antwerp on charges of heresy (May 1535) and his subsequent martyrdom (October 1536), Tyndale was unable to translate the complete Old Testament. Nevertheless, as the diagram shows, all English translations of the Bible produced between 1535 and 1611, including those authorized by the English Church (Great Bible, Bishops’ Bible, King James Bible), were substantially based upon Tyndale’s work. Even the Catholic translators of the Douay–Rheims Bible (1582) referred to Tyndale, though their base text was the Latin Vulgate Bible rather than Greek source text. Because Tyndale was a deeply thoughtful translator who sought to bring his work as close to the literal meaning of the Greek as he could, his translations top the list of the prescribed additional resources that the KJV translators were supposed to use.[12] Nevertheless, the KJV translators owe an immense debt to all of their English predecessors because they contributed heavily to the development of an English way of expressing biblical material.

One illustration, taken from Matthew 1:18–20 is sufficient to demonstrate the way the KJV translators combined portions of earlier English Bible translations to form the King James text.

Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.

Then Joseph her husband, being a just man, and not willing to make her a publick example, was minded to put her away privily.

But while he thought on these things, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost.

The large majority of this passage was taken directly from Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament. However, portions of it were borrowed from other translations. The two underlined words were copied from Myles Coverdale’s 1535 Bible. The italicized words were taken from the Geneva Bible. The bold words are all that remain of the base text, the Bishops’ Bible. The only word that may be original to the KJV translators is espoused.[13] This sample shows that Tyndale provided the basis of the King James text. However, it also demonstrates the amount of revision the KJV translators did and how carefully they selected from the other versions of the Bible that were available to them. This passage also indicates how much of the Bishops’ Bible had to be changed.

The translators began the actual work on the project sometime in the fall of 1604. They took three years to complete the preliminary phases of revision/

Bois notes discussions at 453 places in the Epistles. If his notes are complete, the general meeting deliberated each day over some thirty-two readings. We know from Bois that the members of the meeting engaged in arguments, which were sometimes violent, consulted dictionaries, pored over and discussed current and antique theologians, traced textual variations, studied classical authors to settle questions of diction, thought about style, composed in places original readings. We know from the tenth rule that the meeting deliberated over questions which were so difficult that the translators themselves had reached a deadlock over correct answers.[14]

The final outcome resulted in the KJV text familiar to us today. For example, the marginal annotations for Luke 1:57 demonstrate the stages of the translation process. The Bishops’ Bible reads, “Elizabeths time came that she should bee delivered, and she brought forth a sonne.” The first revision made the following change: “Now Elizabeths time was fulfilled that she should bee delivered, and she brought forth a sonne.” One last change made by the Stationers’ Hall group brings the text into the form familiar to King James Version readers: “Now Elizabeths full time came, that she should bee delivered, and shee brought forth a sonne.”[15] Hundreds, if not thousands, of similar such changes produce a text that echoes familiarity to many Bible readers of today.

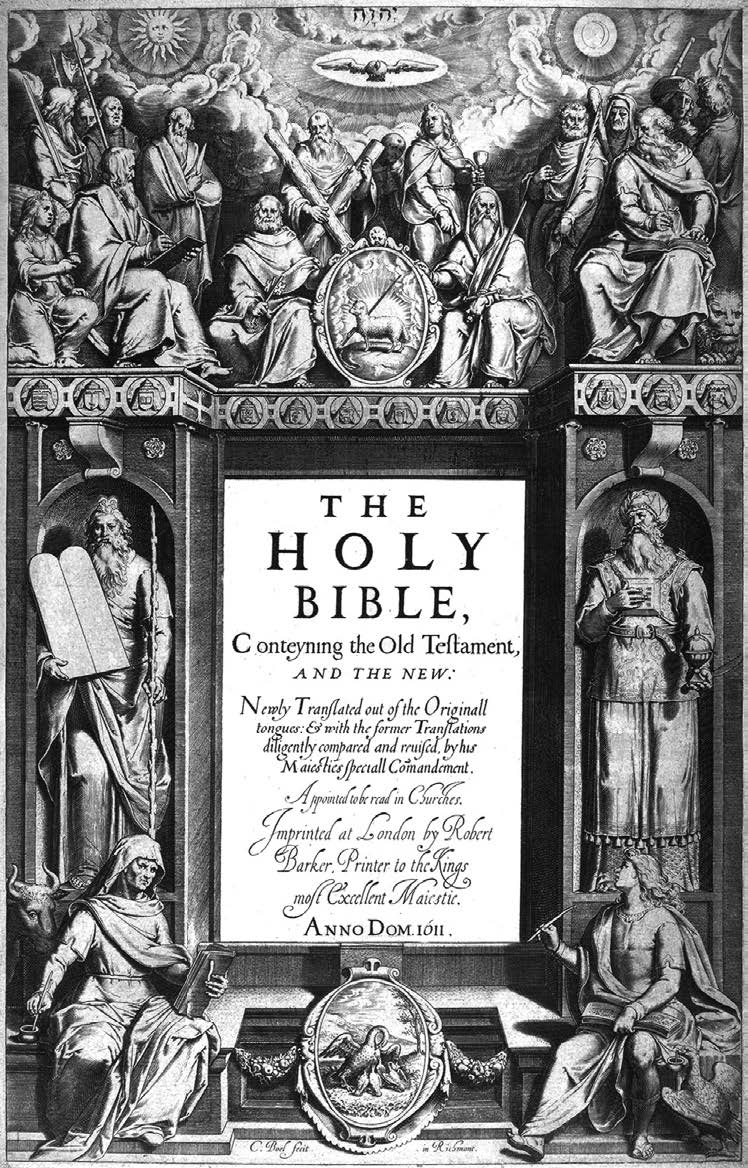

The first edition of the KJV came quietly and without fanfare from the press of Robert Barker, the king’s printer, in 1611.[16] INSERT IMAGE 2 The large, heavy volume, measuring approximately 11 by 16 inches, was designed to sit impressively on a church lectern where it could be read aloud to the congregation. The text was printed in two columns per page, with cross-references in the interior and exterior margins and brief chapter summaries placed before the first verse of each chapter. In addition to the actual biblical text, a decorative title page was affixed that contained the following inscription: “THE HOLY BIBLE, Conteyning the Old Testament, and the New. Newly translated out of the originall tongues: & with the former Translations diligently compared and revised, by his Maiesties speciall Comandement. Appointed to be read in Churches. Imprinted at London by Robert Barker, Printer to the Kings most Excellent Maiestie. Anno Dom. 1611.” Following the title page, there was a three-page dedication of the work to King James, “the Most High and Mightie Prince,” followed by the translators’ preface, calendars of church festivals, prayers and lessons with readings for various church services, a map of the Holy Land, a table of contents listing the books of the Bible and the number of chapters, and thirty-four pages of biblical genealogies. INSERT IMAGE 3

The Language of the King James Bible

While no record exists of King James’s opinion of the KJV, Hugh Broughton, a Puritan Hebrew scholar who had been excluded from the companies of translators, did not approve. He boldly and passionately declared that the translation “bred in me a sadness that will grieve me while I breath. It is so ill done. Tell his Maiest[y] that I had rather be rent in pieces with wild horses, then any such translation by my consent should be urged upon poor Churches. . . . The new edition crosseth me. I require it to be burnt [sic].”[17] One reason that Broughton was so dramatically opposed to the translation was because he felt that the English was out of date.[18] He was right. The English of the 1611 KJV was derived, at least in part, from English that was common sixty or seventy years earlier. However, the translators had a good reason for using a style of English that was not contemporary.

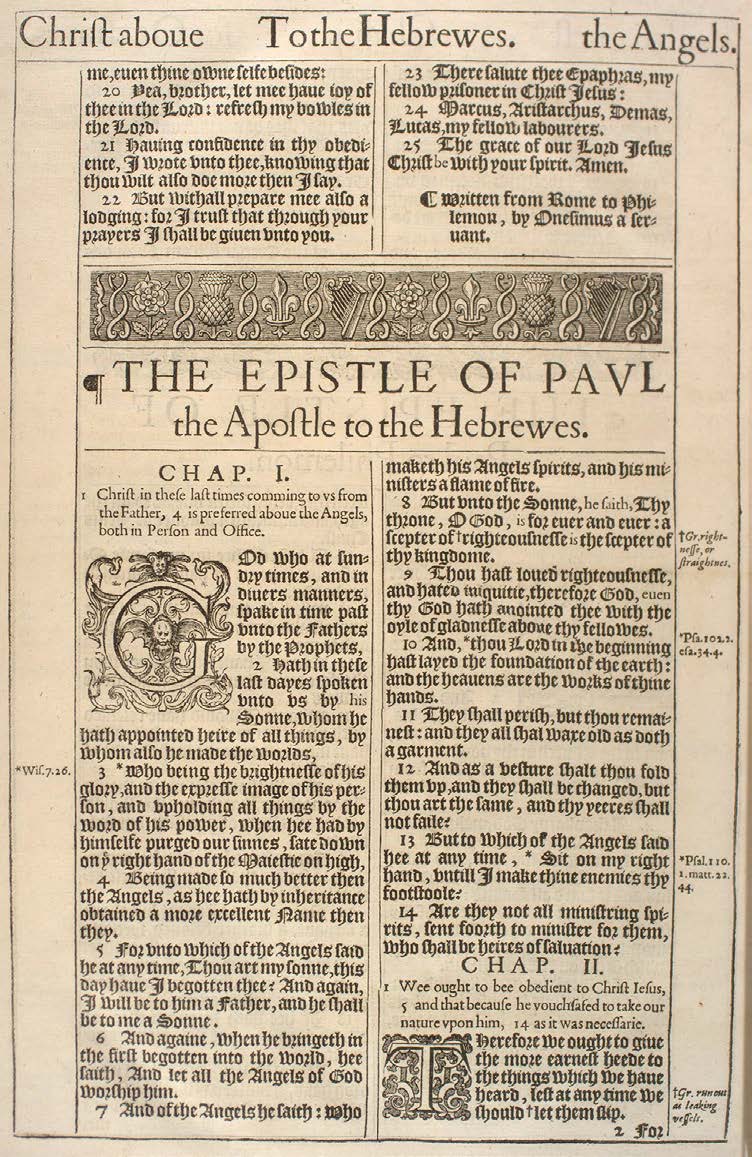

1611 King James Bible, opening of the Epistle to the Hebrews. Public domain

1611 King James Bible, opening of the Epistle to the Hebrews. Public domain

In the preliminaries to the 1611 KJV, Miles Smith, a member of the final revision committee, explained that a good translation opened “the window, to let in the light” and put “aside the curtain, that we may look into the most Holy place.”[19] In other words, the language of the Bible needed to be plain, dignified, and understandable to lay people. However, it should also be rich, resonant and appropriate for a holy place. The language needed to reach up to the sublimity of God while also reaching down to the vulgarity of man.[20] One modern author stated it this way, “Not everyone prefers a God who talks like a pal or a guidance counselor. Even some of us who are nonbelievers want a God who speaketh like––well, God.”[21]

One comparative illustration will demonstrate the difference in the KJV’s heightened language. James 1:5 is well known to the Latter-day Saints and much beloved because of its connection to the Prophet Joseph Smith and the First Vision. The chart below compares the KJV translation with three modern translations.

It is easy to see from this comparison what the KJV translators so thoroughly understood. The seventeenth-century phraseology feels richer and more capable of carrying complex and multiple meanings than most twentieth and twenty-first century translations do. Flattened language, language that is submissive to its audience, loses some, if not all, of its ability to move, challenge, chastise, and inspire.[22] It is true that the language of the KJV can be strange and difficult in places, but strange does not mean incomprehensible and difficult does not always mean detrimental.

Title page, 1611 King James Bible. Public domain.

Title page, 1611 King James Bible. Public domain.

The most noticeable and substantial archaic aspects of the King James language are the verb forms (hath, doeth, shalt, begat, etc.) and the pronouns (thee, thy, thou, thine, etc.). Fortunately, these are very manageable with careful attention and a little practice. However, two other types of words can significantly obscure the meaning of the text for a modern reader: (1) English words that are no longer in use today and (2) English words that have changed in meaning over time. The second type occurs much more often in the KJV than the first, but it is worth providing examples of both.

Obsolete English Words and English Words with Altered Meanings

Of the roughly 12,000 different words that make up the text of the KJV, less than one 1 percent are archaic, and even fewer than one percent are obsolete. Thus, the large majority of the language in the KJV is accessible to the modern English-speaker. However, the obsolete and archaic words should not be ignored, which is why the Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV sometimes provides clarifying footnotes. One example of an obsolete word is the word “assay.” Assay means “to try to do, attempt, or venture.”[23] It appears six times in the KJV, three times in the Old Testament and three times in the New Testament, but because assay is not currently in use in everyday speech, its meaning may be obscure to most modern readers. A student of the New Testament will encounter “assay” for the first time in Acts 9:26 when Saul comes to Jerusalem after his conversion to Christ: “And when Saul was come to Jerusalem, he assayed to join himself to the disciples: but they were all afraid of him, and believed not that he was a disciple.” Unfortunately, there is no explanatory footnote next to assay to aid the reader in understanding its meaning. The same is also true for the two other passages where it appears in the New Testament: Acts 16:7 and Hebrews 11:29. The only place in the Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV where it does have an explanatory footnote is in the Old Testament. In Deuteronomy 4:34, Moses exhorts the children of Israel to keep the commandments. He asks, “Or hath God assayed to go and take him a nation from the midst of another nation, by temptations, by signs, and by wonders, and by war, and by a mighty hand, and by a stretched out arm, and by great terrors, according to all that the Lord your God did for you in Egypt before your eyes?” A superscript a next to assayed correctly states in the footnote that the word means “attempted.” With this explanation, an inaccessible term suddenly becomes accessible. However, this is only true for those who study the Deuteronomy verse. Unfortunately for readers, no cross-references connect this helpful footnote to any of the later passages where “assay” appears in the Old or New Testaments.

A similar problem occurs with words whose meanings have changed over time. For example, the word “reins” appears fifteen times in the KJV, fourteen in the Old Testament and once in the New Testament. When first encountering this word, a modern reader will likely assume that reins is the plural of “rein,” which means “a long narrow strap attached to the bridle or bit of a horse or other animal.”[24] However, applying the “long narrow strap” definition to any verse where “reins” appears results in a completely different meaning from what was intended. “Reins” is actually an archaic word that refers to “the region of the kidneys” and represents the “seat of the feelings or affections.”[25] This use of “reins” is no longer part of everyday speech. This time, the only helpful footnote for “reins” is in the New Testament. Thus, readers who encounter “reins” for the first time in the Old Testament will struggle to make sense of it because there are no cross-references linking the Old Testament passages to the explanatory footnote in the New Testament. “Reins” appears in Revelation 2:23 during a recitation of what will happen to a seductress named Jezebel. The verse states, “And I will kill her children with death; and all the churches shall know that I am he which searcheth the reins and hearts: and I will give unto every one of you according to your works.” A superscript b next to “reins” explains that it represents a Greek word meaning “desires and thoughts.” Though it is certainly helpful to know what the underlying Greek meaning is, the footnote does relatively little to assist the reader in understanding the English meaning of “reins.” The footnote also fails to explain why this form of “reins” is an appropriate English equivalent for the Greek word. Thus, even with the helpful insight about the Greek term, “reins” could remain an unfamiliar and difficult English word for many readers. It is evident from these two examples, that some words in the KJV are inaccessible to a modern reader unless explanatory help is given. Though the Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV does supply needed assistance, improvements could be made to the frequency of the clarification and to the type of clarification provided.

KJV Translation and the New Testament

When the KJV was first printed in 1611, it contained a translators’ preface near the beginning that was written by Miles Smith, a member of the final revision committee. In that eleven-page introduction, “The Translators to the Reader,” he stated, “So hard a thing it is to please all, even when we please God best, and do seek to approve ourselves to every one’s conscience.”[26] The preface set forth the reasoning behind the making of the new translation: the translators believed that the Bible was God’s word and that it should be available in the language of the people. Even in translation, Smith wrote, the words of scripture are of great worth: “If we be ignorant, they will instruct us; if out of the way, they will bring us home; if out of order, they will reform us; if in heaviness, comfort us; if dull, quicken us; if cold, inflame us. . . . Love the Scriptures, and wisdom will love thee.” To help allay concerns about the accuracy and value of the translation Smith added the following:

We affirm and avow, that the very meanest [most humble] translation of the Bible in English, set forth by men of our profession . . . containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God. As the King’s speech which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the King’s speech, though it be not interpreted by every translator with the like grace.… No cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it.[27]

As evinced by “The Translators to the Reader,” the translators of the KJV were aware that there were “some imperfections and blemishes” in their new Bible. Even though many of them were excellent scholars in their own right and relied on some of the best scholarly tools available in their day, the translation sometimes falls short of accurately conveying the sense of the underlying Greek as it is easy to miss every idiom, subtilty, and nuance.[28] This is especially the case with the Greek text of the New Testament. By the time of the KJV translation, the Greek language in the New Testament source texts had not been spoken for over a millennium. While the translation appearing in the New Testament of the KJV is mostly accurate, perhaps at times even exemplary, there are nonetheless places where the translation either misses the original meaning of the text or where the rendering is almost unintelligible––at least by twenty-first century standards. Therefore, to help the reader of the KJV New Testament better understand the actual text and what the first-century authors were trying to convey we have provided below a list of fifty instances, presented in canonical order, where the translation needs to be either corrected or revised. We have by no means offered an exhaustive list of New Testament corrections nor have we treated any passages where text-critical factors are at play but have only focused on the actual translation of the underlying Greek text. Our only purpose here is to help the reader better understand the original meaning of the text in places where the KJV has translation problems or errors.

|

Passage |

KJV Translation |

Explanation and Better Translation |

|

|

1. |

Matthew 5:15; Mark 4:21; Luke 8:16; 11:33, 36; Revelation 18:23; 22:5 |

“candle” |

In these passages the Greek word is λύχνος (luchnos), which has the literal meaning of “lamp.” Here Jesus is not talking about candles, which would be anachronistic, but about oil lamps. |

|

2. |

Matthew 6:25, 31, 34 |

“take no thought” |

The Greek verb used here is μεριμνάω (merimnaō), which means “be anxious, or unduly concerned.” Thus, the counsel given by Jesus in this section of the Sermon of the Mount is to “not be anxious” or “unduly concerned” about worldly things when the apostles were on the Lord’s errands. |

|

3. |

Matthew 10:4 |

“Simon the Canaanite, and Judas Iscariot, who also betrayed him.” |

The Greek term for the KJV “Canannite” is κανανίτης (kananitēs; or more probably καναναῖος), and it is simply a Greek rendering of the Hebrew קנאה (qn’h), which has the meaning “zeal.” Thus, it should read “Simon the Zealot” (see also Luke 6:15 and Acts 1:3). |

|

4. |

Matthew 13:21; compare Mark 6:25; Luke 17:7; 21:9 |

“Yet hath he not root in himself, but dureth for a while: for when tribulation or persecution ariseth because of the word, by and by he is offended.” |

The phrase “by and by” is a translation of the Greek adverb εὐθέως (eutheōs), which means “immediately” or “at once.” Thus, “immediately he is offended.” Compare Mark 4:17. |

|

5. |

Matthew 17:24 |

“And when they were come to Capernaum, they that received tribute money came to Peter, and said, Doth not your master pay tribute?” |

The Greek word used here is δίδραχμον (didraxmon) and literally means “double drachma.” In the Greek rendering of the Old Testament (LXX) this term is used in Exodus 30:11–16 to signify the “half shekel” temple tax that was to be paid annually by all males twenty years and older. In this verse the same meaning applies: “Does your master pay the temple tax?” The KJV rendering “tribute” misses the point. |

|

6. |

Matthew 22:17 (compare Matthew 22:19; Mark 12:14; Luke 20:22) |

“Tell us therefore, What thinkest thou? Is it lawful to give tribute unto Caesar, or not?” |

In these verses the Greek word is κῆνσος (knēsos), from which our English word “census” is derived. The meaning is not “tribute” but rather a certain kind of “tax,” namely the “poll tax” or “capitation tax” that all non-Roman citizens were obliged to pay. Thus, the question being asked Jesus was whether it was lawful to pay “taxes.” This was a loaded question because openly declaring that Roman taxes should not be paid was a punishable offense under Roman law. |

|

7. |

Matthew 23:24 |

“Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel.” |

The Greek verb is διϋλίζω (diulizw) and means “filter out” or “strain out.” Thus, a better rendering is “strain out a gnat.” |

|

8. |

Matthew 27:34 (compare Matthew 27:48; Mark 15:36; Luke 23:36; John 19:29–30) |

“They gave him vinegar to drink mingled with gall: and when he had tasted thereof, he would not drink.” |

The Greek word is ὄξος (oxos) and instead of “vinegar,” which is a lexical possibility, the best rendering is “sour wine” or “ordinary wine.” Thus, “They gave him sour wine to drink.” This type of wine was considered of a lower quality than ordinary “wine” (οἶνος; oinos) because it had moved along in the fermentation process and was considerably more bitter, nevertheless, it had not yet fermented to the extent that it had become “vinegar”—from an alcohol to an acetic acid. Anciently people did not drink vinegar because it was not palatable. This kind of “sour wine” was known to have been commonly imbibed by Roman soldiers. |

|

9. |

Mark 5:30 (compare Luke 6:19; 8:46) |

“And Jesus, immediately knowing in himself that virtue had gone out of him, turned him about in the press, and said, Who touched my clothes?” |

The Greek word is “power” (δύναμις; dunamis). The present usage of “virture” may have come from Latin influence of virtus that has the meaning of “power.” |

|

10. |

Mark 6:20 |

“For Herod feared John, knowing that he was a just man and an holy, and observed him; and when he heard him, he did many things, and heard him gladly.” |

The Greek verb is συντηρέω (suntērew) and properly means “preserve together” or “keep safe from damage or loss.” In this verse the point is being made that Herod Antipas initially “protected” John or “kept him safe” from the threats of Herodias who desired to have John killed (compare Mark 6:17–19). |

|

11. |

Luke 2:1 |

“And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.” |

The Greek verb used here is ἀπογράφω (apographō) and has the principal meaning of “to register” or “to enroll.” Thus, the “decree” of Augustus was “that all the world should be registered.” Here it is referring to a census registration that would serve as the basis for which taxation would be later based. |

|

12. |

Luke 4:13 |

“And when the devil had ended all the temptation, he departed from him for a season.” |

The Greek phrase is ἄχρι καιροῦ (arxi kairou) and has the more accurate meaning of “until an opportune time.” The Greek καιρός has the meaning of “right time” or “right moment.” Thus, Luke is stating that after the devil withdrew from Jesus during the temptations that he would return at an opportune time—when the devil thought Jesus might be vulnerable to temptation. |

|

13. |

Luke 22:32 |

“But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not: and when thou art converted, strengthen thy brethren.” |

The Greek verb is ἐπιστρέφω (epistrephw), and though it can have the meaning of “conversion” it literally means “to be turned” or “returned.” Thus, Peter is to strengthen the brethren after he has “returned.” |

|

14. |

John 5:39 |

“Search the scriptures; for in them ye think ye have eternal life: and they are they which testify of me.” |

The Greek verb is ἐραυνάω (ernaunaw), and though it does mean “search” or “examine,” as implied in the KJV translation, it is to be taken in another mood. Whereas the KJV translators took it in the imperative mood: “search,” the Greek mood is the indicative, which is not a command but a statement of fact: “You are searching the scriptures.” Thus, the meaning of the verse is not that Jesus is commanding his Jewish interlocutors to “search the scriptures” but rather, “You are searching the scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that are testifying of me.” |

|

15. |

John 14:18 |

“I will not leave you comfortless: I will come to you.” |

The Greek word is ὀρφανός (orphanos), literally “orphan.” Therefore, “I will not leave you as orphans.” |

|

16. |

John 20:17 |

“Jesus saith unto her, Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God.” |

The Greek verb is ἅπτω (haptō) and means “to touch” or “to hold.” Here it appears in the imperative mood with the middle voice, meaning that the action is already occurring. Thus, instead of “Touch me not,” a better rendering would be “Stop holding on to me.” This is actually a very tender moment in John where upon recognizing the risen Christ Mary takes hold of him (compare Matthew 28:7). |

|

17. |

Acts 1:20 |

“For it is written in the book of Psalms, Let his habitation be desolate, and let no man dwell therein: and his bishoprick let another take.” |

This verse quotes from Psalm 69:25 (LXX 68:26) and 109:8 (LXX 108:8). The term “bishoprick” (from LXX Ps 108:8) comes from the Greek ἐπισκοπή (episkopē) that just means “office” or “leadership.” Thus, “and his office let another take.” When this Psalm is translated in the KJV it is rendered as follows: “Let his days be few; and let another take his office.” |

|

18. |

Acts 1:22 |

“Beginning from the baptism of John, unto that same day that he was taken up from us, must one be ordained to be a witness with us of his resurrection.” |

This word does not appear in the Greek; the KJV supplies the word ordained from the Tyndale translation, but the Greek only says that it was necessary for one of these “to become a witness of his resurrection with us.” The focus here was on providing scriptural authority for taking Judas’s office away as well as installing his replacement, who was already known to the Lord. |

|

19. |

Acts 5:30 |

“The God of our fathers raised up Jesus, whom ye slew and hanged on a tree.” |

This phrase does not have the conjunction “and” in Greek; the verb for “hanged” is κρεμάννυμι (kremannumi) and is a participle with the interpretive force being “whom you slew by hanging him on a tree.” |

|

20. |

Acts 7:45 |

“Which also our fathers that came after brought in with Jesus into the possession of the Gentiles, whom God drave out before the face of our fathers, unto the days of David;” |

While the Greek proper name is Ἰησοῦς (iēsous), or Jesus, the actual person being meant here is “Joshua”––the successor of Moses. As Jesus and Joshua share the same name, although it is rendered differently in English, Joshua is meant here (compare Hebrews 4:8). |

|

21. |

Acts 12:4 |

“And when he had apprehended him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four quaternions of soldiers to keep him; intending after Easter to bring him forth to the people.” |

The Greek word here is πάσχα (pascha), which means “Passover.” This is an anachronism in the KJV translation where “Easter” is rendered instead “Passover.” |

|

22. |

Acts 14:12 |

“And they called Barnabas, Jupiter; and Paul, Mercurius, because he was the chief speaker.” |

Here the Greek actually reads “Zeus” (Ζεύς; zeus) and “Hermes” (Ἑρμῆς; hermēs) respectively. “Jupiter” and “Mercury” are the Roman equivalents of “Zeus” and “Hermes.” It is unclear what motivated the translators to render them in the way they did. |

|

23. |

Acts 17:22 |

“Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars’ hill, and said, Ye men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious.” |

The Greek adjective is δεισιδαίμων (deisidaimōn) and in a pejorative sense means “superstitious.” In this instance, Paul is not trying to criticize the Athenians but rather commend them for their religiosity so as to present his message. Thus, a better rendering of the term here is “very devout” or perhaps “very religious” and is being used in a complimentary way. |

|

24. |

Acts 19:24, 27–28, 34–35 |

“Diana” |

Here the Greek reads “Artemis” (Ἄρτεμις; artemis). “Diana” is the Roman equivalent; see Acts 14:12 above. |

|

25. |

Acts 19:37 |

“For ye have brought hither these men, which are neither robbers of churches, nor yet blasphemers of your goddess.” |

The Greek word is ἱερόσυλος (hierosulos) and literally means “a temple robber.” |

|

26. |

Acts 20:28 |

“Take heed therefore unto yourselves, and to all the flock, over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers, to feed the church of God, which he hath purchased with his own blood.” |

The Greek term here is ἐπίσκοπος (episkopos), which can have as one of its principal meanings “overseer,” but also means “bishop.” Every other time the term is found in the NT the KJV renders it bishop: Philippians 1:1, 1 Timothy 3:2, Titus 1:7, 1 Peter 2:25. Thus, a more consistent translation here would be “bishops.” |

|

27. |

Acts 27:17 |

“Which when they had taken up, they used helps, undergirding the ship; and, fearing lest they should fall into the quicksands, strake sail, and so were driven.” |

The word Greek word translated as “quicksands” is Σύρτις (surtis) and is actually the name of two shallow gulfs in the Mediterranean Sea. According to the Greek geographer Strabo (2.5.20), there was the “Greater Syrtis,” the modern Gulf of Sirte off the coast of Libya, and the “Lessor Syrtis,” the modern Gulf of Gabes off the coast of Tunisia. Here the “Greater Syrtis” is being referenced. Thus, a more accurate translation would be: “fearing they would run aground on the sand-bars of Syrtis.” |

|

28. |

Acts 28:11 |

“And after three months we departed in a ship of Alexandria, which had wintered in the isle, whose sign was Castor and Pollux.” |

The Greek word is διόσκουροι (dioskouri) and literally means “sons of Zeus.” These were the twin brothers “Castor” and “Pollux.” A rendering closer to the Greek would be something like “with the Twin Brothers as its figurehead.” |

|

29. |

Acts 28:13 |

“And from thence we fetched a compass, and came to Rhegium: and after one day the south wind blew, and we came the next day to Puteoli:” |

The Greek verb is περιέρχομαι (perierxomai) and means “to go around or about.” In a nautical context, it means “to sail around or about”; thus, “From there we sailed about and came to Rhegium.” |

|

30. |

Romans 11:32 |

“For God hath concluded them all in unbelief, that he might have mercy upon all.” |

The Greek verb rendered “concluded” is συγκλείω (sygkleiō), which has the principal meaning of “shutting in,” “to confine,” or “to imprison.” Thus, God “confined” all in disobedience. |

|

31. |

1 Corinthians 1:18 |

“For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God.” |

In Greek these are participial phrases, so a better rendering is “For the preaching of the cross is to them who are perishing foolishness; but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” |

|

32. |

1 Corinthians 4:4 |

“For I know nothing by myself; yet am I not hereby justified: but he that judgeth me is the Lord.” |

The entire sense of this phrase is distorted in the KJV translation. The verb σύνοιδα (sunoida) can mean “to know,” but a more precise meaning is “to be conscious of.” The reflexive “by myself” is better rendered “against myself.” Thus, “For I am consciousness of nothing against myself.” |

|

33. |

1 Corinthians 13:12 |

“For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” |

The Greek word is ἔσοπτρον (esoptron) and the principal meaning is “mirror”: “For now we see in a mirror dimly.” Ancient mirrors were made from flat pieces of metal that were polished and capable of a dim reflection. |

|

34. |

1 Corinthians 15:19 |

“If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men most miserable.” |

The rendering of this passage is somewhat confusing in the KJV. In this part of 1 Corinthians 15, Paul is making the point that the Corinthians’ “faith” is not in vain regarding the Resurrection and here seems to be subordinating mere “hope” in Christ to genuine “faith” in Christ. Thus, “If in this this life we have only hoped in Christ, we are more miserable than all other people.” |

|

35. |

1 Corinthians 16:22 |

“If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha.” |

The phrase “Anathema Maranatha” (ἀνάθεμα μαράνα θά; anathema marana tha) is a Greek phonetic rendering of an Aramaic phrase, like the ones that sometimes appear in the Gospels: Matthew 27:46, Mark 5:41, 7:34. But in this case no translation is given. The approximate meaning of the phrase “Anathema Maranatha” is “accursed, our Lord, come!” With the addition of the third person Greek imperative command “let him be” (ἤτω; ētō), the meaing of this Greek/ |

|

36. |

Galatians 5:12 |

“I would they were even cut off which trouble you.” |

The Greek verb is ἀποκόπτω (apokoptō) and has the meaning of “cutting or hewing off.” Whenever this verb is used elsewhere in the New Testament is always refers to a literal “cutting off” (Mark 9:43, 45; John 18:10, 26; Acts 27:32). In this verse it appears in the middle voice, which has a reflexive sense, so that it means “to oneself off.” Used is this way it often means “to castrate oneself” or “make oneself a eunuch.” Thus, in this verse Paul is chiding his opponents who are clamoring for circumcision and hyperbolically asserts that they should carry this to its logical conclusion: “I would that those who are troubling you would even emasculate/ |

|

37. |

Galatians 6:11 |

“Ye see how large a letter I have written unto you with mine own hand.” |

The Greek word here is γράμμα (gramma) that has the principal meaning of “writing” or an “alphabet letter.” In this verse Paul is not trying to point out how large a letter he has written, i.e. in terms of length (compare Romans, 1 Corinthians and 2 Corinthians), but rather the size or font in which individual letters have been written. Thus, the verse should be rendered: “You see how large letters I am writing to you with my own hand.” As this comes near the very end of the letter Paul is simply pointing out that he is now personally writing the letter (subscribing) and explaining the sudden change in font size. The implication is that Galatians 1:1–6:10 was written by a scribe or amanuensis and that Paul is now adding a personal touch by writing himself (compare Romans 16:22). |

|

38. |

Philippians 2:7 |

“But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men:” |

The Greek verb is κενόω (kenoō) and principally means “to empty” or “to pour out.” Thus, the rending should be “But [Jesus] emptied himself, and took upon him the form of a servant.” Here Paul is discussing the condescension of Christ and asserting that as part of this process he “emptied himself” of his premortal glory and became mortal. |

|

39. |

Philippians 3:20 |

“For our conversation is in heaven; from whence also we look for the Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ:” |

The Greek word is πολίτευμα (politeuma) and means “citizenship”; thus, “For our citizenship is in heaven.” |

|

40. |

Philippians 3:21 |

“Who shall change our vile body, that it may be fashioned like unto his glorious body, according to the working whereby he is able even to subdue all things unto himself.” |

The Greek word is ταπείνωσις (tapeinōsis) and means “humble” or “low estate.” Thus, a better translation would be something like “Who shall change our humble body, that it may be fashioned like his glorious body.” The point being made is that our present mortal bodies are much lower than Christ’s resurrected body. |

|

41. |

1 Thessalonians 5:3 |

“For when they shall say, Peace and safety; then sudden destruction cometh upon them, as travail upon a woman with child; and they shall not escape.” |

The Greek word rendered “travail” is ὠδίν (ōdin), and though it has the general meaning of “anguish” or “pain,” it is specifically used in the context of “birth pangs” or “labor pains” when a woman is about to give birth. The imagery being invoked here is that the “sudden/ |

|

42. |

Hebrews 4:8 |

“For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day.” |

This should read “Joshua” and not “Jesus.” See note to Acts 7:45 above. |

|

43. |

Hebrews 9:7 |

“But into the second went the high priest alone once every year, not without blood, which he offered for himself, and for the errors of the people:” |

The Greek term is ἀγνόημα (agnoēma) or “a sin of ignorance”; thus, “which he offered for him and for the sins of the people committed in ignorance.” |

|

44. |

Hebrews 10:23 |

“Let us hold fast the profession of our faith without wavering; (for he is faithful that promised;)” |

The Greek word here is ἐλπίς (elpis) and means “hope”; thus, “Let us hold fast to the profession of our hope without wavering.” |

|

45. |

1 Timothy 5:8 |

“But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel.” |

Rather simply “an unbeliever” (ἄπιστος; apistos). |

|

46. |

1 Timothy 6:20 |

“O Timothy, keep that which is committed to thy trust, avoiding profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of science falsely so called:” |

The Greek word is γνῶσις (gnōsis) and means “knowledge.” Thus, “and oppositions of what is falsely called ‘knowledge.’” Here the passages is seemingly referring to the teaching of “Gnosticism.” |

|

47. |

James 3:2 |

“For in many things we offend all. If any man offend not in word, the same is a perfect man, and able also to bridle the whole body.” |

The Greek verb is πταίω (ptaiō) and means “to stumble” or “to fail.” Thus, it should read “For in many things we completely stumble.” |

|

48. |

1 Peter 2:9 |

“But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light.” |

The phrase “a peculiar people” is based on the Greek phrase λαὸς εἰς περιποίησιν (laos eis peripoiēsin) that literally means “a people for [God’s] possession.” It does not mean that God’s people are weird or strange but that they are God’s very own people or possession. The English word “peculiar” is derived from the Latin peculiaris that means “of one’s own property” or “private property.” First Peter 2:9 is quoting Exodus 19:5. |

|

49. |

Revelation 17:6 |

“And I saw the woman drunken with the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus: and when I saw her, I wondered with great admiration.” |

The Greek word is θαῦμα (thauma) and means “wonder or amazement.” John was not in “admiration” of the “great whore” (Revelation 17:1) but rather in “wonder” or “amazement” when he saw this vision of her; thus, “I wondered with great amazement.” |

|

50. |

Revelation 19:17 |

“And I saw an angel standing in the sun; and he cried with a loud voice, saying to all the fowls that fly in the midst of heaven, Come and gather yourselves together unto the supper of the great God;” |

In this phrase the adjective “great” (μέγα; mega) does not modify “God” but rather “supper” so that it should instead read “the great supper of God.” |

Further Reading

Blumell, Lincoln H. "A Text-Critical Comparison of the King James New Testament with Certain Modern Translations." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 67-127.

Bray, Gerald. Translating the Bible: From William Tyndale to King James. Oxford: Latimer Trust, 2010.

Burke, David G., John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner, eds. The King James Version at 400. Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence. Atlanta, SBL, 2013.

Campbell, Gordon. Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611-2011. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Jackson, Kent P., ed. The King James Bible and the Restoration. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011.

Norton, David. The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Notes

[1] Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611–2011 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 1; David Crystal, The King James Bible and the English Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 7.

[2] Philip Goff, Arthur E. Farnsley II, Peter J. Thuesen, “The Bible in American Life,” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 10.

[3] Fred E. Woods, “The Latter-day Saint Edition of the King James Bible” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 260–76.

[4] “First Presidency Statement on the King James Version of the Bible,” Ensign, August 1992, 80.

[5] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Handbook 2: Administering the Church (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2010), 180.

[6] James ruled in Scotland as James VI from July 24, 1567, and then in England and Ireland as James I from 24 March 1603 until his death.

[7] This list is taken from Norton, The King James Bible, 86–89; see also Alfred W. Pollard, ed., Records of the English Bible: The Documents Relating to the Translation and Publication of the Bible in English, 1525–1611 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1911), 53–55.

[8] It appears that guideline 15 was added at a later time.

[9] See Ward Allen, ed., Translating the New Testament Epistles, 1604–1611: A Manuscript from King James’s Westminster Company (Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International for Vanderbilt University Press, 1977), xxviii; see also Norton, King James Bible, 94–106.

[10] King James Version Original Preface [1611], www.kjvbibles.com/

[11] David Norton, The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 7.

[12] In the prologue to his 1525 New Testament translation, Tyndale asked others who were learned in languages to send him suggestions if they “perceive in eny places that I have not attained the very sence of the tonge or meanynge of the scripture or have not geven the right englysshe worde.” In William Tyndale, The New Testament (Cologne: Peter Quentell, 1525), sig. Aiir.

[13] Norton, The King James Bible, 36, 40; Norton notes that “espoused” is also used in Richard Taverner’s Bible (1539), and this may have been where the KJV translators got it from, though it is also possible that the KJV translators thought of it themselves.

[14] Allen, Translating the New Testament Epistles, xxiv.

[15] Quoted in Allen, Translating the New Testament Epistles, xxix.

[16] Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 86, 108.

[17] Hugh Broughton, A censure of the late translation for our churches sent unto a right worshipfull knight, attendant upon the king (Middleburg: R. Schilders, 1611) STC (2nd ed.) / 3847, Early English Books Online, www.eebo.com, sig air.

[18] Broughton, A censure, sig. aivv.

[19] King James Version Original Preface.

[20] Adam Nicholson, God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 227–33.

[21] Charles McGrath, “Why the King James Bible Endures,” New York Times, 23 April 2011, www.nytimes.com/

[22] Nicholson, God’s Secretaries, 153, 236.

[23] Oxford English Dictionary Online, www.oed.com, s.v. “assay.”

[24] Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “rein.”

[25] Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “reins.”

[26] “The Translators to the Reader,” vii. Spelling and capitalization are modernized in this quotation and in those that follow. A good reproduction is found in Erroll F. Rhodes and Liana Lupas, eds., The Translators to the Reader: The Original Preface of the King James Version of 1611 Revisited (New York: American Bible Society, 1997), 27.

[27] “The Translators to the Reader,” xii.

[28] To put it another way, reading the Greek New Testament in translation is like watching a movie in black and white, whereas reading it in the original is like watching the same movie in high definition.