The Saints Flee from Ohio to Missouri

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill

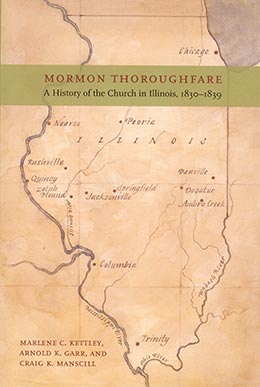

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill, “Zion’s Camp,” in Mormon Thoroughfare: A History of the Church in Illinois, 1830–39 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 79–94.

Marlene C. Kettley was a researcher and historian, Arnold K. Garr was chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

The year 1837 was a time of tragedy for the Church in Kirtland. “The spirit of speculation in lands and property of all kinds, which was so prevalent throughout the whole nation, was taking deep root in the Church,” wrote Joseph Smith. “As the fruits of this spirit, evil surmisings, fault-finding, disunion, dissension, and apostasy followed in quick succession, and it seemed as though all the powers of earth and hell were combining their influence in an especial manner to overthrow the Church at once, and make a final end.” [1]

One sorrowful result of this disunity was that many members left the Church at this time. Some of them even joined forces with Mormon-haters to harass the faithful Saints. The apostates were so mean-spirited that they forced the steadfast members of the Church in Ohio to flee to Missouri in order to escape persecution. This chapter will discuss the events that led to this apostasy. It will also give an account of the members’ mass exodus to Missouri, with special emphasis on their travels along the Mormon thoroughfare of Illinois.

The Road to Apostasy

The historic background to the “Great Apostasy” in Ohio began soon after the Saints completed construction of the Kirtland Temple in the spring of 1836. At that time, many members turned their attention to improving their own homes and increasing their property holdings. During this same period, members from other areas were moving to Kirtland to join with the Saints and live near the temple. At least 250 new members moved to Kirtland in 1836, and approximately 500 more migrated to the community in 1837. [2] As they poured into the city, the demand for homes, jobs, goods, and services increased. “Joseph Smith and other Church leaders had participated in this expansion by purchasing land and merchandise and by extending credit to members who had migrated to Kirtland.” [3] By 1837, a rapidly escalating inflationary economy engulfed the town.

During this time, the Church’s greatest asset was real estate. Latter-day Saint leaders believed that if they could establish a bank they would be able to convert the Church’s “long-term assets (land) into liquid assets (bank notes).” [4] A bank would also “keep money in the town” and “make credit available to the mercantile establishments and shops in the community.” [5]

Unfortunately, the state of Ohio refused to grant a bank charter to the Mormons or anybody else in 1836 and 1837. Undaunted, Church leaders decided to form a joint-stock company on January 2, 1837. They named their financial institution the “Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company,” with Joseph Smith as treasurer and Sidney Rigdon as secretary. It issued anti-banking notes as a medium of exchange.

Almost immediately the safety society ran into trouble. “Heavy demand for redemption in specie (coined money) depleted the bank’s small reserve.” [6] As a result, within a few weeks after the institution had opened its doors, it was forced to suspend specie payments. This caused customers and other financial institutions to quickly lose faith in the safety society. Matters only became worse in May when the National Panic of 1837 caused hundreds of banks to close throughout the United States. The Kirtland Safety Society went out of business in November 1837.

Many people blamed Joseph Smith for the failure of the institution. At least seventeen people filed lawsuits against the Prophet, and many apostatized, including some Church leaders. [7] “A spirit of speculation had crept into the hearts of some of the Twelve, and nearly, if not every quorum was more or less infected,” observed Eliza R. Snow. “As the Saints drank in the love and spirit of the world, the Spirit of the Lord withdrew from their hearts, and they were filled with pride and hatred toward those who maintained their integrity.” [8]

Sadly, some Church leaders even chose to deny Joseph Smith as a prophet and determined to choose a new leader to take his place. “On a certain occasion several of the Twelve, the witnesses to the Book of Mormon, and others of the Authorities of the Church, held a council in the upper room of the Temple,” declared Brigham Young. “The question before them was to ascertain how the Prophet Joseph could be deposed, and David Whitmer appointed President of the Church.” Brigham continued: “I rose up, and in a plain and forcible manner told them that Joseph was a Prophet, and I knew it, and that they might rail and slander him as much as they pleased, they could not destroy the appointment of the Prophet of God, they could only destroy their own authority, cut the thread that bound them to the Prophet and to God and sink themselves to hell.” Obviously, many of the apostates were upset with Brigham. A man named Jacob Bump, a boxer, “was so exasperated that he could not be still.” He ranted, “‘How can I keep my hands off that man?’” Brigham then calmly told Bump that “if he thought it would give him any relief he might lay them on.” The meeting finally broke up “without the apostates being able to unite on any decided measures of opposition.” [9]

Eliza R. Snow wrote about another shameful episode that took place in the temple during this period. This time Warren Parrish was the ringleader of a group of apostates that caused the incident. On a Sunday morning, Parrish and his followers, “armed with pistols and bowie-knives,” went to a meeting in the temple. When they interrupted the meeting, Joseph Smith Sr., the presiding authority, told the dissidents that they would be allowed to speak as long as they wanted, but they must wait their turn. Then “a fearful scene ensued—the apostate speaker becoming so clamorous, that Father Smith called for the police to take that man out of the [temple].” Surprisingly, “Parrish, John Boynton, and others, drew their pistols and bowie-knives, and rushed down from the stand into the congregation; J. Boynton saying he would blow out the brains of the first man who dared to lay hands on him.” As a result, “many in the congregation, especially women and children, were terribly frightened—some tried to escape from the confusion by jumping out of the windows.” Fortunately, no one was injured and eventually the police were able to restore order. Nevertheless, it was a “terrible scene to be enacted in a Temple of God.” [10]

In the fall of 1837, while Joseph Smith was on a mission in Missouri, the spirit of apostasy spread through Kirtland like a plague. “Warren Parrish, John F. Boynton, Luke S. Johnson, Joseph Coe, and some others united together for the overthrow of the Church,” wrote Joseph Smith. “Soon after my return this dissenting band openly and publicly renounced the Church of Christ of Latter-day Saints and claimed themselves to be the old standard, calling themselves the Church of Christ excluding the word Saints, and set me at naught, and the whole Church, denouncing us as heretics.” [11]

As a result of this dissension, “between November 1837 and June 1838, possibly two or three hundred Kirtland Saints withdrew from the Church, representing from 10 to 15 percent of the membership there.” [12] Unfortunately, many of the apostates were leaders in the Church. Although formal Church action was not taken against some of these leaders “until after they had moved to Missouri, the roots of their apostasy” extended back to their activities in Kirtland. “During a nine-month period, almost one-third of the General Authorities were excommunicated, disfellowshipped, or removed from their Church callings. Among those who left the Church during this stormy period were the three witnesses to the Book of Mormon (Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris), four apostles (John F. Boynton, Lyman E. Johnson, Luke S. Johnson, and William E. McLellin), . . . and one member of the First Presidency (Frederick G. Williams) was released from his calling.” [13] It is little wonder that scholars sometimes refer to this period in modern Church history as “the first great apostasy.” [14]

Church Leaders Begin the Exodus to Missouri

The dissidents were so cruel to the steadfast members of the Church that they actually feared for their lives. Brigham Young was forced to flee Kirtland on the morning of December 22, 1837, because the apostates threatened to kill him for proclaiming “publicly and privately” that he knew “by the power of the Holy Ghost, that Joseph Smith was a Prophet of the Most High God.” [15] Brigham traveled as fast as he could to Dublin, Indiana. There he found his brother Lorenzo and several friendly families who had decided to stay there for the winter. Brigham remained in Dublin until other Church leaders arrived. Brigham’s departure from Kirtland in December marked the beginning of a mass exodus of Latter-day Saints from Ohio to Missouri. “Between the end of December 1837 and the middle of July 1838, probably more than sixteen hundred members of the Kirtland branch migrated west, abandoning their homes and beginning a new colonizing adventure in the wilderness of western America.” [16]

On January 13, 1838, three weeks after Brigham Young left Kirtland, Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon also fled “the deadly influence” of the city. The Prophet began his journal for the year 1838 by describing the circumstances that led to their exodus: “A new year dawned upon the Church in Kirtland in all the bitterness of the spirit of apostate mobocracy; which continued to rage and grow hotter and hotter, until Elder Rigdon and myself were obliged to flee . . . , as did the Apostles and Prophets of old, and as Jesus said, ‘when they persecute you in one city, flee to another.’” [17] Eliza R. Snow also declared that Joseph and Sidney had to run “for their lives.” [18]

They left on horseback at about ten o’clock in the evening “to escape mob violence.” They rode through the night for about sixty miles until they came to Norton Township in Medina County, Ohio. There they stayed with friends for about thirty-six hours, waiting for their families to catch up with them. From Norton Township, they traveled with their families in covered wagons for the remainder of the trip. This difficult trek took place in the middle of winter, when it was “extremely cold.” In addition, the mob, “armed with pistols and guns,” followed them for over two hundred miles after they left Kirtland. On one occasion, the enemy actually stayed at the same house in which the Prophet and his party stayed. The partition that separated them was so thin that Joseph could hear the mobbers boasting and bragging about what they would do to the Mormons if they were to catch them. Later in the journey, their antagonists passed them on the street, and even though they “gazed upon” the Saints, they failed to recognize them. [19]

On about January 16, 1838, the Prophet reached Dublin, Ohio, where he met up with his loyal friend Brigham Young. By this time, Joseph Smith had run out of money. He had hired out to cut cord wood but was still not able to earn enough money to pursue his journey to Missouri. So he went to Brigham and said: “As you are one of the Twelve Apostles who hold the keys of the kingdom in all the world, I believe I shall throw myself upon you, and look to you for counsel in this case.” At first Brigham did not believe the Prophet was being serious. However, once he understood that Joseph was in earnest, Brigham told the Prophet to rest himself, and he assured him that he would have “plenty of money to pursue [his] journey.” At that time, a member named Tomlinson lived in Dublin who had previously asked advice of Brother Young about selling his tavern. Brigham had told him that if he would “do right and obey counsel, he should have opportunity to sell soon.” A few days later, Tomlinson received a good offer. Brigham told Tomlinson it “was the hand of the Lord to deliver President Joseph Smith from his present necessity.” [20] Tomlinson sold his tavern and gave the Prophet three hundred dollars, which allowed him to continue his travels.

Joseph, his family, and the rest of his party temporarily left Brigham Young in Dublin and made their way across Indiana and Illinois. Brigham caught up with the Prophet about “four miles west of Jacksonville, Illinois, where there was a Branch of the Church.” They rested in Jacksonville for a few days and then proceeded to Quincy, Illinois. Here they chose to cross the Mississippi River into Missouri. The river was frozen, but the ice was “broken up” and thicker in some places than in others. After Joseph and Brigham examined the ice, they devised a rather unique but precarious strategy for crossing the river. First, they drove their wagons across a flat boat situated on the shore of the river. Then they placed some planks that extended from the flat boat to the heavy ice. They then drove their wagons over the planks and finally on “solid ice” to the other side of the river. Evidently, the ice was not all that solid in some places. Brigham Young said that “the last horse which was led on to the ice was Joseph’s favorite, Charlie. He broke the ice at every step for several rods.” [21]

After the river crossing, Brigham and Joseph continued their journey through Missouri together. When they were about 120 miles from Far West, they met some brethren from that city who had brought wagons and money to assist them on the final leg of their trip. Then when they were about eight miles from Far West, Thomas Marsh and others came to escort them into the city. They arrived in Far West on March 14, 1838, where their friends welcomed them with “open arms.” [22]

Kirtland Camp

Even after Joseph Smith left Kirtland, persecution against the Saints continued to rage in that city. Therefore, most of the faithful members were determined to follow their Prophet to Far West, Missouri, as soon as possible. Over the next several months, there was a steady flow of Saints evacuating their beloved Kirtland. Some traveled by water, while others made the trip by land. Most members migrated to Missouri in groups of fifty or less. However, one important company of over five hundred people made the journey in the summer and fall of 1838. This group became known as Kirtland Camp.

The idea for Kirtland Camp solidified during a series of meetings held by the Seventies in the Kirtland Temple between March 6 and 20, 1838. The presidents of the Seventy were concerned about the “extreme poverty” that existed among the Saints who remained in the Kirtland area. During a meeting on March 10, the Seventies discussed the idea of organizing the poor so they could travel together to Missouri. During this deliberation, “the Spirit of the Lord came down in mighty power, and some of the Elders began to prophesy that if the quorum would go up in a body together, and go according to the commandments and revelations of God, pitching their tents by the way, that they should not want for anything on the journey.” James Foster, one of the presidents of the Seventy, arose and “declared that he saw a vision in which was shown unto him a company (he should think of about five hundred) starting from Kirtland and going up to Zion. That he saw them moving in order, encamping in order by the way, and that he knew thereby that it was the will of God that the quorum should go up in that manner.” According to one account, “The Spirit bore record of the truth of [Foster’s vision] for it rested down on the assembly in power, insomuch that all present were satisfied that it was the will of God that the quorum should go up in a company together to the land of Zion.” [23]

The presidents of the Seventy assumed leadership of the enterprise. They were called the “Councilors of the camp.” However, two of the presidents—Daniel S. Miles and Levi Hancock—were already in the West. Therefore, the five presidents called two assistant councilors to fill the vacancies of Miles and Hancock during the trip. The two assistant councilors were Elias Smith (also the camp scribe) and Benjamin S. Wilber. These two men joined with presidents James Foster, Josiah Butterfield, Zerah Pulsipher, Joseph Young, and Henry Harriman to be the camp councilors. [24]

The Seventies thought it appropriate to submit their plan to Hyrum Smith, second counselor in the First Presidency, for his approval. They invited President Smith to their next meeting on March 13. Under Hyrum Smith’s supervision, they drew up the outlines of a “Constitution for the organization and government of the camp.” The document stated that there would be “one man appointed to preside over each tent,” and there would be approximately eighteen people assigned to a tent. Members of the camp were expected to live the Word of Wisdom—“no tobacco, tea, coffee, snuff or ardent spirits of any kind [were] to be taken internally.” Any faithful member of the Church was welcome to travel with the camp as long as he or she would abide by the rules and regulations. Any person who “behave[0] disorderly” and was not willing to conform to the rules would be “disfellowshiped by the camp and left by the wayside.” [25]

Hyrum Smith heartily approved of the project. He “declared that he knew by the Spirit of God” that the plans the Seventies were making were “according to the will of the Lord.” In addition, “he advised all who were calculating to go up to Zion . . . whose circumstances would admit, to join with the Seventies” in their journey. [26] Along with President Smith, there were many others who were excited about the undertaking. Perhaps the most enthusiastic endorsement came from Oliver Granger. He maintained that “it would be the greatest thing ever accomplished since the organization of the Church or even since the exodus of Israel from Egypt.” [27]

It took more than three months to prepare for the exodus, but finally, on July 5, 1838, the participants began gathering “about a quarter of a mile south of the temple” to prepare for the evacuation. That evening they “pitched their tents in the form of a hollow square.” There they spent the night anxiously awaiting their departure. By most accounts, the company was composed of about 515 pioneers traveling with 59 wagons and 27 tents. They also had “97 horses, 22 oxen, 69 cows and one bull.” [28] It must have been a strange sight the next day to watch that long procession of wagons methodically rumble away from the city of Kirtland.

The camp generally followed the same trail that Joseph Smith’s division of Zion’s Camp had taken in 1834. [29] The daily regimen for Kirtland Camp was fairly structured. A horn awoke the camp every morning at four. Twenty minutes later, the families in each of the twenty-seven tents had prayer (there were three or four families per tent). According to camp regulations, the company was not to travel “more than fifteen miles in one day, unless circumstances . . . absolutely require[0] it.” [30]

Each Sunday the camp held outdoor public worship service and invited the people in the nearby communities to attend. Usually the visitors were cordial, “though there were some exceptions.” [31] On the first two Sundays of their journey, these services were so “thronged with visitors” that the Saints decided not to pass the sacrament. [32]

The first member of the camp to die during the migration was the six-month-old son of Brother and Sister Benjamin Wilbur. The little boy had been ill for two or three days, and he died on July 11, 1838, just six days into the journey. [33] Despite this tragedy and others, the camp also witnessed miraculous healings. One of these took place near Bellefontaine, Ohio, on July 23. A wagon wheel ran over a boy’s leg “on a hard road without any obstruction whatever.” Even though “the wheel made a deep cut in the limb,” the elders administered to the boy, and “he was able to walk considerable in the course of the afternoon.” Elias Smith observed, “This was one, but not the first, of the wonderful manifestations of God’s power unto us on the journey.” [34]

As the journey progressed, more people joined the camp. By July 23, there were 620 members of the camp, according to the company scribe. [35] If that figure is correct, it means that more than one hundred new members joined the company during the first seventeen days of the excursion. As time went on, it became increasingly more difficult to feed the members of the camp. This lack of food provided the backdrop for a miraculous proliferation of food supplies. The official camp record stated that between Marion and Hardin counties in Ohio “provisions were scarce and could not be obtained.” At that time, according to Elias Smith, the Saints experienced “another manifestation of the power of Jehovah, for seven and a half bushels of corn sufficed for the whole camp, consisting of six hundred and twenty souls, for the space of three days, and none lacked for food.” [36]

As one might imagine, the spectacle of over five hundred people traveling together attracted the attention of countless onlookers. Many people were kind to the Saints as they passed by, but others were discourteous and abusive. Some made disrespectful remarks concerning the Mormons and “Jo Smith.” On one occasion, Brother Dunham asked a farmer if the Saints could buy food from him to feed their teams. The farmer threatened to shoot Dunham if he did not get off his property immediately. One time when the Saints had set up camp, a stagecoach drove by and the passengers “behaved . . . more like the savages of the west than anything [they] had seen since the commencement of [their] exodus.” [37]

Kirtland Camp not only had to contend with unpleasant outsiders but also with rebellious members of the company. On several occasions, the presidents of the Seventy, acting as the camp council, exercised their right to expel recalcitrant members from the camp and leave them “by the wayside.” For example, on July 29 the council met to consider the case of Abram Bond, who was charged with “murmuring and not giving heed to the regulations of the camp.” The council voted unanimously that he should be “disfellowshiped by the camp and left to the care of himself.” Accordingly, Brother Bond “left the camp the next day.” [38] On another occasion, “Nathan Staker was requested to leave the camp in consequence of the determination of his wife, to all appearances, not to observe the rules and regulations of the camp. There had been contentions in the tent between herself and Andrew Lamereaux, overseer of the tent. . . . The Council had become weary of trying to settle these contentions between them. . . . The impossibility of Brother Staker to keep his family in order was apparent to all, and it was thought to be the best thing for him to take his family and leave the camp.” [39]

By July 28, the members of the camp had been traveling for about three weeks and had spent nearly all of their money already. They had traveled only 250 miles since they left Kirtland and were less than a third of the way to their ultimate destination of Far West, Missouri. [40] Therefore, they decided to stop traveling for a while so the men could go to work and earn enough money to sustain them for the rest of their journey. They established a semipermanent encampment in a beautiful grove near Dayton. While there, several of the men took jobs building a segment of a turnpike between Dayton and Springfield. Others worked at various jobs in the Dayton area. The turnpike project lasted nearly the entire month of August and paid them one thousand two hundred dollars. [41]

Even though the turnpike superintendent asked the Saints to build another segment of the road, the camp council decided to continue the trek to Missouri. [42] On August 29, they renewed their journey, and two days later they entered Indiana. It took them only eight days to travel through that state. During this time, however, in spite of the fact that the weather was generally “cool and the roads good,” the camp experienced several deaths. E. P. Merriam died on September 2 and was buried in an orchard in Jones Township, Hancock County. The next day, Bathsheba Willey, who had been sick for nearly two months, finally passed away and was buried next to the Merriam child. On Wednesday, September 5, the child of Thomas Nickerson died during the night and was buried on a farm owned by Noal Fouts, which was located west of a small village called Putnamville. Then on Friday, September 7, two more children died: Otis Shumway’s daughter passed away during the night, and in the morning J. A. Clark’s child died. Both children were buried in a cemetery in Terre Haute, Indiana. [43]

Kirtland Camp in Illinois

The camp crossed the state line into Illinois on Saturday, September 8, 1838. It would take them thirteen days to journey across that state, during which time many families decided to separate themselves from the camp. This development was accelerated on September 9, when they had encamped for the night at Ambro Creek. There the council called a special meeting for the heads of families. At this gathering, the council suggested that some of them, “especially those that did not belong to the Seventies,” should consider staying in Illinois for the winter to earn enough money to pay for the rest of their journey to Far West (the camp had already spent most of the money earned building the turnpike). The council felt the Seventies were obliged to get to Missouri as soon as possible so they could continue their primary responsibility of missionary work. The others could work in Illinois during the winter and resume their journey to Missouri in the spring. According to the camp scribe, the recommendation initially “seemed to meet with the approval of a large majority of the heads of families in the camp.” [44]

However, this spirit of unity evidently did not last long because the next day the same recorder wrote: “Considerable anxiety seemed to be manifested by some concerning the advice of the Council, and some complained, like ancient Israel, and said that they did not thank the Council for bringing them so far, and had rather been left in Kirtland.” As a result, the council asked some malcontents to withdraw from the camp, while others simply voluntarily chose to “pursue their journey by themselves.” [45]

By September 14, the camp had reached Springfield, where they experienced a great deal of opposition. The local citizens often made “unrighteous remarks against Joseph Smith and the Church.” During this stage of the journey, the Saints suffered from lack of water: “The drought continues, the water in the wells is very low, and many springs are entirely dry. Many families found stopping places before arriving here.” [46]

That the leaders were not exaggerating when they announced that the camp was almost out of money for supplies is evidenced by this revealing account: “The camp is sometimes short of food, both for man and beast, and they know what it is to be hungry. Their living, for the last 100 miles, has been boiled corn and shaving pudding, which is made of new corn ears. . . . The cobs and remaining corn are given to the horses, so that nothing is lost; hence the proverb goes forth in the world, that the ‘Mormons’ would starve a host of enemies to death, for they will live where everybody else would die.” The account continues: “The camp numbers about 260. There were 515, but they have scattered to the four winds; and it is because of selfishness, covetousness, murmurings and complainings, and not having fulfilled their covenants, that they have been thus scattered.” [47]

While the Saints were in Springfield, several members of the camp were seriously ill. So the council asked Joel H. Johnson if he would stay there for the winter and take care of those who were sick. Consequently, Johnson rented a house in Springfield and attended to the needs of that small band of ailing Saints. However, when other members, who were traveling from the East, heard that Johnson was staying in Springfield, many of them also decided to stop there for the winter. Soon the group was large enough that Johnson organized them into a branch of the Church, over which he was called to preside. The branch soon had “about forty members in good standing.” Johnson remained in Springfield until January 8, 1839, when he moved to Carthage, Illinois. [48] He never made it to Missouri because by January 1839 the Mormons had already been expelled from that state.

On September 18, a small group of Kirtland Camp participants made a decision in Illinois that had dreadful consequences for some. On that day, nine families withdrew from the camp to make their way to Missouri on their own. [49] Some of them ultimately chose to settle in a small Mormon settlement in northern Missouri called Haun’s Mill. On October 30, a group of Missouri mobbers viciously attacked that little village and killed seventeen Latter-day Saint men and boys, leaving dozens of helpless widows and children to fend for themselves. This, of course, was the Haun’s Mill Massacre, one of the most tragic events in Church history. We are indebted to Amanda Smith for recording the heart-wrenching details of that event which were published in the History of the Church. [50] Unfortunately, Amanda’s husband, Warren Smith, was one of the seventeen people killed at Haun’s Mill. [51] Amanda and Warren Smith were part of that group of nine families that had left Kirtland Camp on September 18.

Kirtland Camp in Missouri

The camp left Illinois on September 20. On that date, they crossed the Mississippi River on a steamboat called Rescue. They then camped about a mile outside of a little town called Louisiana in Pike County, Missouri. [52] As soon as the members of Kirtland Camp entered Missouri, ruffians began to threaten them with severe violence. Samuel D. Tyler recorded a threat made on his life. When he was out on the prairie searching for a stray cow, he encountered a couple of men who had crossed the Mississippi River on Rescue with the Mormons. One of the men asked Tyler if he belonged to the “‘gang of Mormons.’” The following dialogue ensued: “‘Are you a Mormon?’ ‘Yes I am.’ ‘Well, stop.’ ‘I am in too much hurry to be stopped, and you have not power to stop me.’ ‘Are you such a fool as to let those people lead you right into danger?’ ‘What danger?’ ‘Why don’t you know the Missourians are raising armies to cut you all to pieces?’ ‘We don’t fear armies.’ ‘G—d d—n you, don’t you fear me?’ said he, at the same time making an attempt to take his arms from his side, for he was armed with a brace of pistols and a dirk. ‘No, I don’t fear you any more than I do any other man.’” Then the harassment became even more intense. “‘Well, G—d d—n ye, what do you fear?’ ‘We fear nothing but God Almighty.’ ‘Well, stop! stop!! damn ye stop!!! or I’ll shoot you down.’ ‘Well, shoot, if you like,’ said I, and passed along, while he kept swearing he would shoot me, ‘and’ said he, ‘you will all get killed before you get up the bluff.’” [53] In spite of these threats, the camp kept moving without being harmed.

Four days later, on September 24, tension increased even more when the camp was traveling through Monroe County. There the local citizens warned the Saints that Governor Lilburn Boggs had organized a militia and was waiting to attack the camp somewhere east of Far West. Once again the camp continued its travels, trusting that the Lord would protect His Saints. [54]

James Foster, one of the presidents of the Seventies, had heard so many rumors of threats that on September 26 he suggested that Kirtland Camp be dissolved. He believed it would be more difficult for the enemy to identify them as Latter-day Saints if the families traveled the rest of the way on their own. However, the other presidents objected to the proposal. While they were discussing the issue, a gentleman named Samuel Bend, who was traveling from Far West to the East, stopped his carriage and came into the camp. He told them that there was “no trouble in Far West and Adam-ondi-Ahman” and that the camp could “go right along without danger.” The council then asked the camp to vote on whether they should continue their journey together, “and instantly all hands were raised toward heaven.” [55]

The Kirtland Camp finally rolled into Far West on October 2, 1838, almost three months after it left Kirtland. During that time, the camp had traveled approximately 870 miles, often under extremely stressful circumstances. [56] Five miles before they entered Far West, the First Presidency of the Church—Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Hyrum Smith—came out to meet them. These leaders, and a few other brethren, received the members of the camp with open arms and “escorted them into the city.” There they camped for the night “on the public square, directly south and close by” a site chosen for a temple. Isaac Morley contributed some beef, and Sidney Rigdon prepared a good meal for many travelers who had eaten very little for several days. [57]

The next day, on October 3, members of the camp continued their journey a final twenty-two miles to Adam-ondi-Ahman, where they would settle for a short time. Upon their arrival at that city on October 4, one enthusiastic brother from the area proclaimed: “Brethren, your long and tedious journey is now ended; you are now on the public square of Adam-ondi-Ahman. This is the place where Adam blessed his posterity, when they rose up and called him Michael, the Prince, the Archangel, and he being full of the Holy Ghost predicted what should befall his posterity to the latest generation.” [58]

Unfortunately, Adam-ondi-Ahman would not be their final destination, and their long, arduous trek would not bring an end to their trials. Within a few weeks, Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs would issue a decree that would force the entire Mormon population to leave the state.

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 2:487.

[2] Milton V. Backman Jr., The Heavens Resound: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Ohio, 1830–1838 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 140.

[3] L. Dwight Israelsen, “Kirtland Safety Society,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 621–22.

[4] Israelsen, “Kirtland Safety Society,” 622.

[5] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1958), 13.

[6] Israelsen, “Kirtland Safety Society,” 622.

[7] Backman, The Heavens Resound, 323.

[8] Eliza R. Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1884), 20.

[9] Brigham Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1801–1844, ed. Elden Jay Watson, (Salt Lake City: Smith Secretarial Service), 15–16.

[10] Eliza R. Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, 20–21.

[11] Smith, History of the Church, 2:528.

[12] Backman, The Heavens Resound, 328.

[13] Backman, The Heavens Resound, 328.

[14] For example, see Karl Ricks Anderson, Joseph Smith’s Kirtland (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 213; Backman, The Heavens Resound, 327; and Church History in the Fulness of Times (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2000), 176.

[15] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 24.

[16] Backman, The Heavens Resound, 342.

[17] Smith, History of the Church, 3:1.

[18] Eliza R. Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, 22.

[19] Smith, History of the Church, 3:1–3.

[20] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 24–25; Smith, History of the Church, 3:2.

[21] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 25–26.

[22] Smith, History of the Church, 3:8–9.

[23] Smith, History of the Church, 3:88–89.

[24] Smith, History of the Church, 3:90–91, 93.

[25] Smith, History of the Church, 3:89–91.

[26] Smith, History of the Church, 3:94.

[27] Smith, History of the Church, 3:96.

[28] Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941), 403. Estimates of the number of people in the company vary slightly. For example, History of the Church says “there were in the camp 529 souls present—a few necessarily absent” (3:100).

[29] Backman, The Heavens Resound, 344, 358.

[30] Smith, History of the Church, 3:102–3.

[31] Smith, History of the Church, 3:101.

[32] Smith, History of the Church, 3:112.

[33] Gordon Orville Hill, “A History of Kirtland Camp: Its Initial Purpose and Notable Accomplishements” (master’s thesis: Brigham Young University, 1975), 33; Smith, History of the Church, 3:104.

[34] Smith, History of the Church, 3:113.

[35] Smith, History of the Church, 3:114.

[36] Smith, History of the Church, 3:114.

[37] Smith, History of the Church, 3:116.

[38] Smith, History of the Church, 3:117, 128.

[39] Smith, History of the Church, 3:128–29.

[40] Smith, History of the Church, 3:116.

[41] Hill, “History of Kirtland Camp,” 61–62; Smith, History of the Church, 3:119–20.

[42] Hill, “History of Kirtland Camp,” 91.

[43] Smith, History of the Church, 3:132–36.

[44] Smith, History of the Church, 3:137; Hill, “History of Kirtland Camp,” 102.

[45] Smith, History of the Church, 3:137–38.

[46] Historical Record, 7:599.

[47] Historical Record, 7:599–600.

[48] Times and Seasons, March 1840, 77.

[49] Hill, “History of Kirtland Camp,” 113–14; Smith, History of the Church, 3:140–41.

[50] Smith, History of the Church, 3:323–25.

[51] Alexander L. Baugh, “Haun’s Mill Massacre,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 473–74.

[52] Smith, History of the Church, 3:141.

[53] Historical Record, 7:600.

[54] Smith, History of the Church, 3:143; Historical Record, 7:601.

[55] Historical Record, 7:601–2; Smith, History of the Church, 3:144.

[56] Smith, History of the Church, 3:147; Historical Record says they traveled 866 miles (7:603).

[57] Historical Record, 7: 602–3; Smith, History of the Church, 3:147.

[58] Smith, History of the Church, 3:148.