Quincy, Illinois: A Temporary Refuge

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill

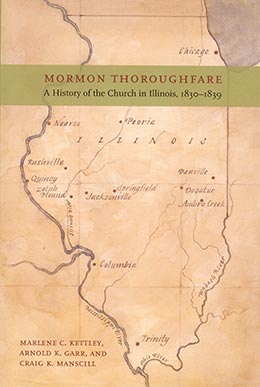

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill, “Zion’s Camp,” in Mormon Thoroughfare: A History of the Church in Illinois, 1830–39 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 95–112.

Marlene C. Kettley was a researcher and historian, Arnold K. Garr was chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

“The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state,” proclaimed Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs on October 27, 1838. “Their outrages are beyond all description." [1] This shameful “extermination order” is perhaps the most infamous statement in the history of the Latter-day Saints. [2] The governor issued this decree after apostates and Mormon haters had given him distorted and exaggerated reports that accused the Latter-day Saints of insurrection. Ignoring any information he received concerning the Mormon point of view, Boggs was led to believe that the Latter-day Saints were making “open war upon the people” of Missouri. [3] The governor then commissioned the state militia to carry out the extermination order. Within the next three days, approximately 2,500 troops had converged on the Latter-day Saint community of Far West, calling for the Mormons to surrender. By October 31, 1838, the Saints submitted to the demands of the militia and agreed to leave Missouri. [4] As a result, approximately ten thousand Saints were forced to evacuate the state during the winter and spring of 1838–39. [5] The greatest number of those exiled Saints—perhaps as many as five thousand—sought temporary refuge in Adams County, Illinois, primarily in the city of Quincy. [6] The purpose of this chapter is to tell the short-lived but vitally important story of the Saints in Quincy, Illinois.

The Road to Quincy

On the evening of October 31, 1838, General Samuel D. Lucas, commander of the Missouri State Militia at Far West, Missouri, arrested Joseph Smith and several leaders of the Church, including Sidney Rigdon, Parley P. Pratt, Lyman Wight, and George W. Robinson. The following day Lucas also took Hyrum Smith and Amasa Lyman into custody. The officers of the militia then held a court-martial, which ruled that the Mormon leaders should be executed. [7] General Lucas issued an order to General Alexander Doniphan that decreed, “‘Sir:—You will take Joseph Smith and other prisoners into the public square of Far West, and shoot them at 9 o’clock to-morrow morning.’” [8] However, when Doniphan received the order, he was outraged by the unfairness and cruelty of the proceedings. He immediately sent a scathing reply to his superior officer, which stated: “‘It is cold-blooded murder. I will not obey your order. My brigade shall march for Liberty tomorrow morning at 8 o’clock; and if you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God.’” [9] Doniphan’s fearless response to Lucas saved the lives of the Prophet and his fellow prisoners.

Frustrated by Doniphan’s defiant reply, General Lucas decided to take Joseph Smith and the other captured Church leaders to Independence, Missouri, in Jackson County, where he paraded them in front of their old enemies. [10] The soldiers then took the prisoners to Richmond, where they appeared before Judge Austin A. King in a corrupt judicial hearing November 12–28. At the conclusion of this arraignment, Judge King determined that Parley P. Pratt and four others should stay in Richmond to be tried later by a circuit court. The judge then ruled that Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, Lyman Wight, Caleb Baldwin, and Alexander McRae be sent to Liberty, Clay County, “to stand . . . trial for treason and murder.” [11] Leaving on November 30, the prisoners were incarcerated in the Liberty Jail by December 1. Rigdon was released in February due to illness, but the others remained in prison, primarily at Liberty, for the next four and a half months. [12]

In the meantime, the Latter-day Saints at Far West were forced to flee Missouri without the help of the Prophet. On November 4, General John B. Clark and 1,600 troops arrived at Far West two days after General Lucas had left to take Joseph Smith and his associates to Independence. [13] General Clark immediately assumed command of the state militia at Far West and was determined to carry out the extermination order.

Prior to Clark’s arrival, General Lucas had imposed four demands upon the Saints in order for them to save their lives: first, that their leaders be given up to be tried; second, that they surrender their arms; third, that they sign over their property to defray the cost of war; and fourth, that they leave the state. [14] The first three terms had already been accomplished before Clark arrived. It was then General Clark’s responsibility to make sure that the Saints left the state.

Clark arrested fifty-six men and paraded them through the streets of the city. He told them that if the Saints had not complied with the first three demands of General Lucas that their “families would have been destroyed” and their houses would have been “in ashes.” Clark then said that the governor had given him discretionary power that he would exercise it in favor of the Saints “for a season.” He explained that they would not have to leave immediately but could remain in the state until spring. “As for your leaders,” he taunted, “do not once think—do not imagine for a moment—do not let it enter your mind that they will be delivered, or that you will see their faces again, for their fate is fixed—their die is cast—their doom is sealed.” Clark then warned the Saints against gathering together in a large body at a central place: “I would advise you to scatter abroad, and never again organize yourselves with Bishops, Presidents, etc., lest you excite the jealousies of the people and subject yourselves to the same calamities that have now come upon you.” [15]

Even though General Clark said the Saints did not have to evacuate the state until spring, the disgraceful behavior of the militia created an environment in which it was almost unbearable for the Saints to live. The troops plundered the Saints’ “bedding, clothing, money, wearing apparel, and every thing of value they could lay their hands upon,” wrote Brigham Young. The militiamen also attempted “to violate the chastity of the women in sight of their husbands and friends, under the pretense of hunting for prisoners and arms. The soldiers shot down our oxen, cows, hogs and fowls, at our own doors, taking part away and leaving the rest to rot in the streets.” [16]

Under these deplorable circumstances, many Saints who had the means and ability fled the state individually as soon as possible. “Those who did not or could not leave Missouri in November and December crowded together in Far West and nearby cluster settlements, sharing roofs, yards, outbuildings, clothing, and food. Hundreds of refugees stood in need of help.” [17]

During this time, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball stepped forward in Joseph Smith’s absence and exhibited remarkable leadership ability. By January 1839 Thomas B. Marsh, the original President of the Quorum the Twelve Apostles, had apostatized. David W. Patten, the next in seniority, had been killed at the battle of Crooked River in October. That meant that Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball were now the senior Apostles. On January 16, 1839, Joseph Smith and his two counselors, Sidney Rigdon and Hyrum Smith, wrote from Liberty Jail to Elders Young and Kimball and told them that “the management of the affairs of the church devolves on you.” [18]

Brigham Young’s immediate concern was to help the poor and needy leave the state. On Saturday, January 26, the Church leaders at Far West called a meeting to devise a plan to comply with the demand to leave the state. Those in attendance appointed a committee of seven men “to ascertain the number of families who are actually destitute of means for their removal.” The members of the committee were Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, John Taylor, John Smith, Don C. Smith, Theodore Turley, and Alanson Ripley. The participants in the meeting also agreed “that it is the duty of those who have, to assist those who have not.” [19]

On January 29, the Saints met again. On this occasion, Brigham Young made the motion “that we this day enter into a covenant to stand by and assist each other to the utmost of our abilities in removing from this state, and that we will never desert the poor who are worthy, till they shall be out of the reach of the exterminating order of General Clark, acting for and in the name of the state.” [20] Those who were at the meeting created a seven-man committee on removal, which had the responsibility of supervising the exodus of “the poor from the state of Missouri.” The chair of the committee was William Huntington, and the other six members were Charles Bird, Alanson Ripley, Theodore Turley, Daniel Shearer, Shadrach Roundy, and Jonathan Hale. [21] They then drew up a formal covenant, which asked the subscribers to commit all of their “available property, to be disposed of by a committee . . . for the purpose of providing means for the removing from this state of the poor and destitute who shall be considered worthy, till there shall not be one left who desires to remove from the state.” [22] Remarkably, over the next two days, Brigham Young was able to persuade at least 380 people to sign the compassionate document. On February 1, four more people were added to the removal committee: Elias Smith, Erastus Bingham, Stephen Markham, and James Newberry. [23]

Quincy, Illinois, was the principal destination for the impoverished Mormons living in and around Far West. Quincy was a logical choice for many reasons. First, it was the closest major city to the Saints that was beyond the borders of Missouri. It was a thriving community with a population of about 1,600 people located on the east side of the Mississippi River. [24] The city was situated approximately two hundred miles east of Far West. [25] Second, it had excellent ferryboat facilities to help the exiles cross the Mississippi River and escape from Missouri. [26] Third, the Saints were familiar with the area. [27] Samuel H. Smith and Reynolds Cahoon visited Quincy in 1831 on their way to Missouri. According to Lucy Mack Smith, “they preached the first sermon that ever was delivered in that town.” [28] Thereafter, several missionaries served in the region during the 1830s with moderate but steady success. For example, in 1833 George M. Hinkel wrote from the Quincy area to the Evening and Morning Star: “Every few days there are some honest souls born into the kingdom of God. The work progresses slow in this region, but sure. The hearts of the people are hard, but when they do come, they are firm in the faith.” [29] Soon thereafter, in 1834, the division of Zion’s Camp that came from Michigan, under the direction of Hyrum Smith and Lyman Wight, passed through Quincy on June 5, and bought some lead. On that occasion, Elijah Fordham wrote favorably of the town, saying it was a place of “about 70 houses, 2 Inns, 9 Stores, [and] an Open Square in the Center . . . [which] looks well.” [30] Gradually the Latter-day Saint population in Quincy grew, and by 1838 some of the members living in the town included Mary Jane York, William A. Hickman, John P. Greene, and Wandle Mace. [31]

By early February, the committee on removal at Far West was doing all in its power to help the poverty-stricken Latter-day Saints get out of Missouri and over to the safe haven of Quincy. The members of the committee gave highest priority to helping the families of the First Presidency and the other members who were in jail. [32]

Committee member Stephen Markham escorted Emma Smith and her children on their passage to Quincy. They left Far West on February 6, and took part in an extremely arduous yet inspirational journey. [33] The night before they left, Ann Scott gave Emma Smith the manuscript of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible. The Prophet’s secretary had given the papers to Ann to care for, thinking that the mob might be less likely to search a woman than a man. Ann had sewn two cotton bags to carry the documents, which she hid under her dress during the day. Emma used these same bags to carry the valuable manuscript to Illinois. On February 15, Emma and her children arrived at the west bank of the Mississippi River, across from Quincy. On that day Stephen Markham returned to Far West, leaving the family to cross the frozen Mississippi without his help. Emma walked across the icy river, carrying two small children in her arms and the manuscript under her dress. The family soon found shelter near Quincy at the home of Judge John and Sarah Cleveland. They lived with the Clevelands until April, when the Prophet Joseph arrived in town after his four-month imprisonment in the Liberty Jail. [34]

Joseph Smith’s parents, Joseph Smith Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith, also fled to Quincy in February. In spite of all the persecution his family had endured in Far West, the Prophet’s father was still not willing to leave Missouri unless the move was approved of by God. So he wrote to his son “to know if it was the will of the Lord” that they should leave the state, “whereupon Joseph sent him a revelation which he had received while in prison, which satisfied [his father], and he was willing to remove to Illinois as soon as possible.” [35]

Soon thereafter the Prophet’s brother William Smith took his family to Quincy, then to Plymouth, where he eventually settled. He then sent his team of horses back to Far West to help his father and mother make the journey. Joseph Sr. and Lucy packed their goods into a wagon and were about to depart when a man came by and said it was needed for Sidney Rigdon’s family. So the Smiths promptly unpacked their supplies and deferred to the Rigdons. The Smiths then waited “a season longer” until William could send them the team again. The Smiths loaded their supplies on the wagon, only to unpack a second time so that their daughter-in-law Emma could use the outfit for her supplies. Finally, after waiting “a long time,” Joseph Sr. and Lucy were able to obtain a wagon that was large enough to carry provisions not only for themselves but also for the families of two of their daughters and their son: Catherine Smith Salisbury, Sophronia Smith McCleary, and Don Carlos Smith. [36]

Their first day of travel was somewhat uneventful and took them to Tenney’s Grove, where they stayed overnight in an old log house, “spending a rather uncomfortable time.” On the second day, Mother Smith was required to travel on foot half the time, and Father Smith became increasingly ill with a “severe cough.” That night they stayed with a member of the Church, Mr. Thomas. On the third day, it began to rain in the afternoon. They stopped at the home of a complete stranger and asked if they could stay the night. The resident showed them a poorly kept outbuilding “filthy enough to sicken the stomach, even to look at,” and told them they could stay there if they would clean the place up and haul their own wood. The Smiths agreed to the terms and stayed through the night in the building without a fire.

The next day before they departed, the inconsiderate landlord charged the Smiths seventy-five cents for staying on his property overnight. The Smiths paid and then spent the rest of the day traveling in the rain. They asked for shelter several times during the day but were turned down every time until it started to get dark. Finally, they came upon a place to stay, but unfortunately the accommodations were “very much like where [they] had spent the night before.” Nevertheless, they stayed the night, once again without a fire.

During the fifth day of travel, Joseph Smith Sr. became so sick that his son Don Carlos determined to stop at the first place that looked “comfortable” and plead with the landlord to let them stay. They soon came to a “handsome, neat-looking farmhouse.” Don Carlos approached the landlord and earnestly implored: “I have with me an aged father, who is sick, besides my mother and a number of women with small children. We have now traveled two days and a half in the rain, and we shall die if we are compelled to go much further. If you will allow us to stay with you overnight, we will pay you any price for our accommodations.”

To their delight, the landlord turned out to be a compassionate, gracious host. He “helped each one of the family into the house and hung their cloaks and shawls up to dry, saying he never in his life saw a family so uncomfortable from the effects of rainy weather.” The landlord, “whose name was Esquire Mann, did all that he could do to assist us,” wrote Lucy. He “brought us milk for our children, hauled us water to wash with, furnished good beds to sleep in, and more. In short, he left nothing undone.” [37] Esquire Mann was a good Samaritan to the Smiths in the middle of an otherwise horrendous journey.

The next day, they left the hospitality of Esquire Mann and continued their travels in mud and rain until they “arrived within six miles of the Mississippi River.” Here the ground became so swampy that they were forced to walk in mud above their ankles “at every step.” To make matters worse, it became colder and began to snow and hail. In the midst of this miserable weather, they were forced to walk because it was too muddy for the horses to pull them. [38]

When they finally arrived at the Mississippi River, they could not cross or find suitable shelter because there was already a large group of Saints waiting “to go over into Quincy.” By this time, “the snow was six inches deep and still falling.” However, the Smiths were exhausted, so they made their “beds on the snow” and tried to get some sleep. When they awoke the next morning, their beds were “covered with snow.” It took a great deal of effort to fold up their bedding because much of it had frozen during the night. They tried unsuccessfully to light a fire, so they waited in the cold, wintry weather until it was their turn to cross the river. Finally, their son Samuel “came over from Quincy” and with the help of Seymour Brunson made arrangements with a ferryman to take the Smiths across the Mississippi. They arrived at dusk in Quincy, where Samuel had rented a house for them. There they stayed with five other families, waiting for the unforeseen future. [39]

At the same time the Smiths were fleeing Missouri, Brigham Young was also making his escape. From January 16 to February 14, Brigham had been directing the evacuation from Missouri. In this capacity, he had become the “‘most wanted’ Mormon” in the state. [40] Apostates and anti-Mormons were now actively seeking his life, and it was no longer safe for him to stay in Missouri. Brigham Young’s own account of his exodus states, “I left Missouri with my family, leaving my landed property and nearly all my household goods, and went to Illinois, to a little town called Atlas, Pike county, where I tarried a few weeks; then moved to Quincy.” [41] The Young family’s journey through Missouri was “dangerous and traumatic.” They had to deal with “frostbite, illness, and threats to their lives.” More than once, “Brigham left his family in camp or at the house of a friendly family” and took his team to help others who were fleeing. On one occasion, while he was gone, “their infant daughter was thrown from a wagon and run over,” but miraculously, she survived. [42]

A Compassionate Haven at Quincy

By the time Brigham Young arrived in Quincy, the people of that community had already opened their homes and provided relief for numerous exiled Latter-day Saints. Unlike the cruel militia in Far West, Missouri, which was only two hundred miles away, the citizens of Quincy distinguished themselves with innumerable acts of kindness and compassion. With scores of Saints pouring into Quincy almost daily, the townspeople decided to organize themselves in an effort to better assist the impoverished exiles. The Democratic Association of Quincy was especially helpful in this cause. On February 25, the organization met and passed a resolution that stated that the people called Latter-day Saints were “in a situation requiring the aid of the citizens of Quincy” and recommended that “measures be adopted for their relief.” The association appointed an eight-person committee, with J. W. Whitney as chairman. [43] The committee was to investigate the conditions of the Saints and make recommendations on how to assist them.

Whitney and his coworkers promptly interviewed several Latter-day Saints, including Elias Higbee, John Greene, and Sidney Rigdon, and asked them to prepare a written statement explaining their situation. Summarizing the plight of the Saints, Higbee wrote: “We have been robbed of our corn, wheat, horses, cattle, cows, hogs, wearing apparel, houses and homes, and, indeed, of all that renders life tolerable.” He also recorded that approximately twenty of the refugees were widows. As for help from the citizens of Quincy, Higbee simply requested: “Give us employment, rent us farms, and allow us the protection and privileges of other citizens.” He felt that this would raise the Saints “from a state of dependence” and liberate them “from the iron grasp of poverty.” [44]

On February 27, the Democratic Association met again. Mr. Whitney reported the findings of his committee and submitted Elias Higbee’s statement to the organization. Near the end of the meeting, they invited Sidney Rigdon to address the association and discuss the abuses that the Mormons had suffered. The Quincy Whig, the local newspaper, reported that Rigdon took the floor “and in a very eloquent and impressive manner related the trials, sufferings and persecutions which his people have met with at the hands of the people of Missouri. We saw the tears standing in the eyes of many of his people while he was recounting their history of woe and sorrow.” The article continued, “In fact, the gentleman himself was so agitated at different periods of his address that his feelings would hardly allow him to proceed.” [45]

The committee was obviously moved by the heart-wrenching accounts of abuse and suggested several resolutions. First, that the Latter-day Saints were to receive their “sympathy and kindest regard,” and they asked “the citizens of Quincy to extend all the kindness in their power to bestow on the persons who are in affliction.” Second, “that a numerous committee be raised” to help the impoverished Mormons, and if the committee members found Latter-day Saints that were destitute, sick, or homeless, they were to “appeal directly and promptly to the citizens of Quincy to furnish them with the means to relieve all such cases.” Third, that the members of the committee “use their utmost endeavors to obtain employment for all these people.” And finally, in all their dealings with the Mormons, that they “be particularly careful not to indulge in any conversation or expressions calculated to wound their feelings.” [46]

The Democratic Association had a third meeting on February 28. At this time they took the opportunity to denounce the disgraceful acts of the state of Missouri against the Latter-day Saints. They stated “that the inhabitants upon the western frontier of the state of Missouri . . . [had] violated the sacred rights of conscience, and every law of justice and humanity.” They also formally resolved “that the governor of Missouri . . . [had] brought a lasting disgrace upon the state over which he presides.” [47]

At about the same time the citizens of Quincy were organizing their efforts on behalf of the Saints, the exiled Saints were also holding meetings to decide to attempt, once again, to permanently settle at a specific gathering place. As of February 1839, Joseph Smith had not designated a precise gathering spot. Quincy was merely serving as a convenient, friendly, but unofficial, place of refuge.

In February, some of the Church leaders called a meeting in Quincy “to take into consideration the expediency of locating the Church in some place.” Specifically, a man by the name of Isaac Galland had offered to sell the Church “about twenty thousand acres, lying between the Mississippi and Des Moines rivers [in Lee County, Iowa], at two dollars per acre, to be paid in twenty annual installments, without interest.” At this time Joseph Smith was still in jail, and Brigham Young had not yet arrived in Quincy. Many of the men in the meeting freely gave their opinion about the proposed real estate deal. William Marks “observed that he was altogether in favor of making the purchase, providing that it was the will of the Lord that we should again gather together.” Wandle Mace “spoke in favor of an immediate gathering.” Elias Higbee “said that he had been very favorable to the proposition of purchasing the land and gathering upon it.” However, Bishop Edward Partridge stated that “it was not expedient under the present circumstances to collect together, but thought it was better to scatter into different parts and provide for the poor.” Partridge’s opinion prevailed, at least for that meeting, and those in attendance determined that it was not “advisable to locate on the lands for the present.” [48]

Bishop Partridge’s idea of scattering, however, did not last long. Soon after Brigham Young arrived in Quincy, he spoke boldly in favor of gathering. At a meeting held on March 17, he said it was wise “to unite together as much as possible.” [49] On the following day, he “met in council with several of the Twelve Apostles, and advised them all to locate their families in Quincy for the time being,” that they might “be together in council.” He then read a letter from Isaac Galland concerning the property that Galland hoped to sell to the Church. Brigham “advised the brethren to purchase land there,” for they would probably move northward. [50] Soon thereafter Joseph Smith wrote two letters to the Church in Quincy which advocated gathering. On March 20 he encouraged the Saints to “secure to themselves . . . the Land which is proposed to them by Mr Isaac Galland.” [51] Then on March 25 he counseled all those “who understand the spirit of the gathering” to “fall into the places and refuge of safety that God shall open unto them, between Kirtland and Far West.” [52] Although the Prophet did not officially designate an exact gathering spot, he did make it clear that the Saints should stay together and not go off on their own.

The Return of the Twelve to Far West

During this time, when the concept of gathering was crystallizing, the members of the Quorum of the Twelve were considering their position concerning a revelation Joseph Smith had received on July 8, 1838. The revelation stated that the Twelve should depart on April 26, 1839, from the “building spot” of the Far West Temple to go on a mission “over the great waters” to the British Isles. [53] Since that revelation had been given, Governor Boggs had issued the extermination order, and many felt that it was not safe for the Quorum of the Twelve to go back into Missouri for the official departure of their mission.

Brigham Young called a meeting in Quincy on March 18 to discuss the matter. While many believed that “the Lord would not require the Twelve to fulfil his words to the letter” because it was so dangerous, Brigham felt differently. In addition, all the members of the Twelve who were at the meeting “expressed their desires to fulfil the revelation.” “I told them the Lord God had spoken,” declared Brigham, “and it was our duty to obey and leave the event in his hands and he would protect us.” [54]

A month later, the time came for the Twelve to fulfill Joseph Smith’s prophecy. On April 18, Brigham Young, Orson Pratt, Wilford Woodruff, John Taylor, and George A. Smith, in company with Alpheus Cutler, departed the friendly confines of Quincy and headed back to the most perilous place in the world for Latter-day Saints—Far West, Missouri. They crossed the Mississippi River that night and then traveled about thirty miles each day. On April 21, when they were just west of Huntsville, Missouri, the party encountered a number of members of the Church headed the opposite direction. A compassionate Brigham Young observed: “The roads were full of the Saints, who were fleeing from Missouri to Illinois, having been driven from their houses and lands by the exterminating order of Governor Boggs.” One of those Saints was John E. Page, an Apostle who was taking his family to Quincy. Elder Page’s wagon had “turned bottom-side upwards,” and a “barrel of soft soap” had spilled. While Elder Page was “elbow deep in the soap, scooping it up with his hands,” President Young asked him to join with the other Apostles and go back to Far West. Elder Page stopped scooping his suds long enough to say “he did not see that he could, as he had his family to take to Quincy.” However, President Young declared that Elder Page’s “family would get along well enough” without him. When Page asked how much time he could have to get ready, President Young replied, “five minutes.” The Twelve helped Elder Page reload his wagon, and soon thereafter Elder Page and his fellow Apostles started for Far West. [55]

On April 23, the Apostles camped about six miles from Tenney’s Grove and about thirty miles from Far West. There they met Elias Smith, Theodore Turley, and Hyrum Clark, “who had been driven from Far West.” Smith and Turley were members of the committee on removal. Turley told the Apostles that on April 16 a mob came to Far West and gave him a paper containing Joseph Smith’s revelation, directing the Twelve to depart on their mission to the British Isles from Far West on April 26. The leader of the mob taunted Turley, saying this “was one of Joe Smith’s revelations which could not be fulfilled, as the Twelve and the Saints were scattered to the four winds.” [56] Hearing of this threat, however, only strengthened the resolve of the Apostles.

“Early on the morning of the 26th of April, we . . . proceeded to the building spot of the Lord’s House” in Far West, wrote Brigham Young. The members of the Twelve in attendance were Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Pratt, John E. Page, and John Taylor. The Twelve ordained Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith as Apostles. (These two had previously been sustained, but not ordained, in Quincy.) “The Twelve then offered up vocal prayer” in order of seniority and sang the hymn “Adam-ondi-Ahman.” This historic meeting did not last long because it was held under such perilous conditions. Nevertheless, the Twelve took great satisfaction in what they had accomplished. Brigham Young put the episode into perspective with these words: “Thus was this revelation fulfilled, concerning which our enemies said, if all other revelations of Joseph Smith were fulfilled that one should not, as it had day and date to it.” [57]

The Apostles and those who were with them hurriedly left Far West and traveled thirty-two miles to Tenney’s Grove, where they spent the night. While they were encamped, they “learned that a mob had collected in different places, and on their arrival in Far West” had found that the Twelve had already been there and transacted their business. When Brigham Young discovered that enemies of the Church had gathered again to harass the Saints, he was determined to get the remaining members out of the state and beyond the reach of the mob. “We had entered into a covenant to see the poor Saints all moved out of Missouri to Illinois,” wrote Brigham, “that they might be delivered out of the hands of such vile persecutors, and we spared no pains to accomplish this object.” The next morning, on April 27, the Twelve left Tenney’s Grove and took “the last company of the poor with [them].” [58] They also took several members of the committee on removal, who had worked under hazardous conditions for three months to evacuate the poverty-stricken Saints from the state.

The Arrival of Joseph Smith in Quincy

When the Apostles returned to Illinois on May 2, they were excited to hear that their beloved Prophet, Joseph Smith, had escaped from prison and was staying at the home of Judge John Cleveland on the outskirts of Quincy. The following day, May 3, the Twelve rode out to the Cleveland residence to meet with the Prophet and his brother Hyrum. As one might imagine, their reunion was a memorable experience. “It was one of the most joyful scenes of my life,” declared Brigham Young, “to once more strike hands with the Prophets and behold them free from the hands of their enemies; Joseph conversed with us like a man who had just escaped from a thousand oppressions and was now free in the midst of his children.” [59]

Joseph Smith had escaped from jail on April 16 and arrived in Quincy on April 22 “amidst the congratulations” of his friends and the “embraces” of his family. [60] Since the Prophet’s arrival, he had been working feverishly to buy land for the Church and make preparations for a permanent gathering place. On April 24, Joseph Smith presided over a council meeting that decided to send him, Bishop Vinson Knight, and Alanson Ripley up the Mississippi River to find a place for the Church to permanently relocate. The council also advised as many Saints as were able to “move north to Commerce, [Illinois] as soon as they possibly” could. [61]

By May 1, the Prophet and his party had purchased for the Church at Commerce “a farm of Hugh White, consisting of one hundred and thirty-five acres, for the sum of five thousand dollars; also a farm of Dr. Isaac Galland, lying west of the White purchase, for the sum of nine thousand dollars.” [62] During the next few months, the Church purchased thousands of acres on both sides of the Mississippi River in Iowa and Illinois, but these original acquisitions in Commerce became the nucleus of a town soon to be renamed Nauvoo—the next great gathering place for the Saints.

Soon after Joseph Smith purchased the land in Commerce, he hurried back to Quincy so he could preside over an important conference. The first and only general conference of the Church held near Quincy, Illinois, occurred May 4–6 in the year 1839. This historic event took place at a Presbyterian camp ground just beyond the city limits.

The conference unanimously adopted several significant resolutions during the three days it met. It acknowledged Elder George A. Smith, who had been ordained in Far West, as an Apostle. It sanctioned the “mission intended for the Twelve” to go to the British Isles. It decided to send President Sidney Rigdon as a delegate to Washington DC to lay before the “General Government” the Church’s case of being expelled from the state of Missouri. It appointed Lyman Wight to gather affidavits that were to be sent to the nation’s capital. [63] In these affidavits, or petitions for redress, the Saints were formally to document their property lost and afflictions suffered during the Missouri persecutions.

The conference also made several important decisions that essentially established Commerce (later renamed Nauvoo) as the next permanent gathering place for the Church. It “entirely” sanctioned the land purchases recently made in behalf of the Church. It appointed William Marks “to preside over the Church at Commerce.” It called Bishop Newel K. Whitney to “go to Commerce, and there act in unison with the other Bishops of the Church.” Finally it resolved that “the next general conference be held on the first Saturday in October . . . , at Commerce.” [64]

On May 9, three days after the general conference at Quincy adjourned, the Prophet Joseph Smith and his family moved to Commerce. They arrived the following day and established residence “in a small log house on the bank” of the Mississippi River. [65] This marked the beginning of the end for Quincy as a refuge. The Church maintained a presence in the region for several years, but thousands of Saints migrated from Quincy to Commerce and the surrounding area over the next several months.

During this mass exodus to Commerce, some notable events took place in Quincy. A future Apostle named Ezra T. Benson converted to the Church in Quincy on July 19, 1840. [66] Then two months later, on September 24, the Church organized a short-lived stake in the city, with Daniel Stanton as president. However, the stake was “reduced to an ordinary branch of the Church in 1841, which in February, 1843, had a membership” of only seventy-seven people. [67]

The story of the Latter-day Saints in Quincy, therefore, is a brief but vitally important episode in the history of the Church. Quincy served as a compassionate, temporary refuge during the Saints’ darkest hour. From the time Governor Boggs expelled them from Missouri, in October 1838, until Commerce became a permanent gathering place for the Church in May of 1839, Quincy was a haven. That was where Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve distinguished themselves as exceptional leaders in managing the affairs of the Church while Joseph Smith was in prison. Specifically, they were responsible for organizing the effort to assist the poverty-stricken Saints in their exodus from Missouri. Quincy was also where the leaders of the Church made the decision to gather in Commerce.

This period was perhaps the finest hour for the citizens of Quincy as they demonstrated extraordinary benevolence in their dealings with the Mormons. On February 3, 1841, Joseph Smith presented to the Nauvoo City Council the following resolutions which paid a fitting tribute to the residents of Quincy: “Resolved . . . that the citizens of Quincy be held in everlasting remembrance, for their unparalleled liberality and marked kindness to our people, when in their greatest state of suffering and want.” [68]

When the Church designated Commerce as the new official gathering place for the Saints, it was an important turning point in Latter-day Saint history. It marked the end of an era when Illinois played the role as a thoroughfare between two gathering spots outside of the state. Illinois then took center stage in Church history. The Church’s golden age—the Nauvoo era—began.

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1964), 3:175.

[2] The “extermination order” was rescinded in 1976 (see Conference Report, October 1976, 4–5).

[3] Smith, History of the Church, 3:175.

[4] Alexander L. Baugh, “Extermination Order,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 351.

[5] Estimates of the number of Mormons living in Missouri in 1838–39 vary from 15,000 down to 5,500. Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Elias Higbee wrote of 15,000 (see Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions [Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992], 116). B. H. Roberts used a figure of 12,000–15,000 (see A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, [Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965], 1:511). James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard also used 12,000–15,000 (see The Story of the Latter-day Saints, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976], 134). Hyrum Smith claimed there were 12,000–14,000 (see Smith, History of the Church, 3:424). Andrew Jenson wrote of 12,000 in Caldwell and Davies County (see Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, [Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941], 107). Parley P. Pratt said there were “10 or 11 thousand souls” (Johnson, Mormon Redress Petitions, 95). William G. Hartley used a figure of 10,000 to 12,000 citizens (see “Missouri’s 1838 Extermination Order and the Mormons Forced Removal to Illinois,” in A City of Refuge: Quincy, Illinois, ed. Susan Easton Black and Richard E. Bennett, 6). Church History in the Fulness of Times uses 8,000–10,000 (see page 215). Glen M. Leonard said at least 8,000 (see Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002], 31). Alexander L. Baugh estimates from 5,500 to 8,000 (see “Mormon Population Figures in Northern Missouri in 1839,” 3; an unpublished paper in the possession of the authors; used by permission).

[6] The figure of approximately 5,000 Mormons in Quincy is used by at least three authors. Susan Easton Black uses the figure 5,600 (see “Quincy—A City of Refuge” in Black and Bennett, A City of Refuge, 76). Quincy mayor Charles W. Scholz used a figure of more than 5,000 (see Black and Bennett, A City of Refuge, xv). Alexander L. Baugh wrote of 5,000 (see “Mormon Population Figures in Northern Missouri in 1839,” 3).

[7] See Smith, History of the Church, 3:188–90

[8] Smith, History of the Church, 3:190n.

[9] Smith, History of the Church, 3:190–91n.

[10] See Smith, History of the Church, 3:200–1.

[11] Smith, History of the Church, 3:208–9, 212.

[12] See Smith, History of the Church, 3:215, 263–64, 319–20.

[13] See Smith, History of the Church, 3:201.

[14] See Smith, History of the Church, 3:203.

[15] Smith, History of the Church, 3:202–4.

[16] Brigham Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1801–1844, comp. Elden Jay Watson (Salt Lake City: Smith Secretarial Service, 1968), 29–30.

[17] Hartley, “Missouri’s 1838 Extermination Order,” in Black and Bennett, A City of Refuge, 9.

[18] Joseph Smith, Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, ed. Dean C. Jessee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 424.

[19] Smith, History of the Church, 3:249–50.

[20] Smith, History of the Church, 3:250.

[21] Smith, History of the Church, 3:251, 254.

[22] Smith, History of the Church, 3:251.

[23] Smith, History of the Church, 3:254–55.

[24] The figure of 1,600 residents for Quincy in 1839 is used by at least two authors (see Susan Easton Black, “Quincy—A City of Refuge,” 76, and Richard E. Bennett, “‘Quincy, the Home of Our Adoption’: A Study of the Mormons in Quincy, Illinois 1838–1840,” in Black and Bennett, A City of Refuge, 86.

[25] See Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church, 688. Jenson explains, “Quincy, was about 150 miles in a straight line, but the way the roads ran it was nearly 200 miles.”

[26] Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church, 2:3.

[27] Bennett, “Quincy, the Home of Our Adoption,” in Black and Bennett, A City of Refuge, 86–87.

[28] Lucy Mack Smith, The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by his Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 280.

[29] Evening and Morning Star, July 1833, 109.

[30] Craig K. Manscill, “‘Journal of the Branch of the Church of Christ in Pontiac, . . . 1834’: Hyrum Smith’s Division of Zion’s Camp,” BYU Studies 39, no. 1 (2000): 182.

[31] Bennett, “Quincy,” 87.

[32] Smith, History of the Church, 3:255.

[33] Smith, History of the Church, 3:256.

[34] Robert J. Matthews, “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1985), 99–100; Carol Cornwall Madsen, “Smith, Emma Hale,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 5 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1324; Leonard, Nauvoo, 36; Smith, History of the Church, 3: 262.

[35] Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith, 410.

[36] Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith, 410; see also History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Preston Nibley (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), 293–94, including notes 1–3.

[37] Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith, 411–13.

[38] Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith, 413.

[39] Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith, 414; see also History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Preston Nibley, 296–97. Proctor and Proctor said the Smiths stayed with five families. Nibley said they stayed with four families.

[40] Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Knopf, 1985), 70.

[41] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 33.

[42] Arrington, Brigham Young, 70.

[43] Smith, History of the Church, 3:263.

[44] Smith, History of the Church, 3:269–70.

[45] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1973), 283–84.

[46] Smith, History of the Church, 3:268–69.

[47] Smith, History of the Church, 3:271.

[48] Smith, History of the Church, 3:260–61.

[49] Smith, History of the Church, 3:283.

[50] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 34.

[51] Smith, Personal Writings, 439.

[52] Smith, History of the Church, 3:301.

[53] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 35; see also Doctrine and Covenants 118:4–5.

[54] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 35.

[55] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 35–36.

[56] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 37.

[57] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 37–39.

[58] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 39.

[59] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 40.

[60] Smith, History of the Church, 3:326–27.

[61] Smith, History of the Church, 3:336.

[62] Smith, History of the Church, 3:341–42.

[63] Smith, History of the Church, 3:344–46.

[64] Smith, History of the Church, 345–47.

[65] Smith, History of the Church, 3:349.

[66] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1901), 1:101.

[67] Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church, 688.

[68] Smith, History of the Church, 4:293.