Missionaries and Converts in Illinois 1835–38

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill

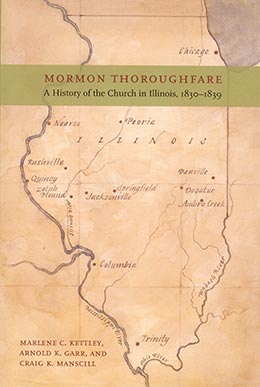

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill, “Zion’s Camp,” in Mormon Thoroughfare: A History of the Church in Illinois, 1830–39 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 63–78.

Marlene C. Kettley was a researcher and historian, Arnold K. Garr was chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

In February 1831, when the Church had only about three hundred members, Joseph Smith received a revelation in Kirtland that admonished the missionaries to “go forth into the regions round about, and preach repentance unto the people.” The elders were then promised that if they did so, “many [would] be converted” (D&C 44:3–4). Soon thereafter, this revelation began to be fulfilled in a remarkable way.

By 1835 the gospel message had spread like fire across the northeastern United States and Canada. Missionaries had already preached in sixteen of the twenty-four states of the Union. They had proselytized all the states in the Northeast except Delaware and Maryland. [1]

Not surprisingly, the number of missionaries rapidly increased during the first six years of the Church’s existence. In early years, missionary statistics were not nearly as accurate as they are today, but the Church has published some interesting figures nevertheless. In 1830 the Church set apart only sixteen missionaries. However, the numbers quickly multiplied, and in 1835 the Church set apart eighty-four elders. At least 382 missionaries received formal calls to serve between 1830 and 1835. [2] All of these elders labored in the United States and Canada. The Church did not call missionaries to serve outside of North America until 1837, when the British Mission was organized. [3]

Missionaries experienced a considerable amount of success throughout the northeastern United States. By the end of 1835, the Church’s 382 elders had already baptized at least 8,835 members. [4] That is an average of over twenty-three converts per missionary. There were probably some unofficial, self-appointed missionaries who accounted for some of these baptisms, but the figures are nonetheless impressive.

Between 1830 and 1835, several developments took place in the young Church that enhanced the missionary effort. One of these was the establishment of Church periodicals. The first publication that the Church printed was The Evening and the Morning Star, founded at Independence in 1832 but moved to Kirtland in December 1833 because of mob violence in Missouri. [5] It was replaced by the Latter-day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, which was established at Kirtland in October 1834 and continued until September 1837. [6] Later on, this paper was succeeded by the Elders’ Journal, which was published from October 1837 to August 1838, first in Kirtland and then in Far West, Missouri. [7] Each of these periodicals devoted a considerable amount of space to “communications,” or reports that the missionaries in the field sent to these papers for publication.

During the first five years of its existence, the Church also made a concerted effort to provide training for its missionaries. In January 1833, the School of the Prophets was established in Kirtland, which was taught in the Newel K. Whitney Store. [8] Later that year, during the summer, the Church organized the School of Zion in Missouri, which was taught by Parley P. Pratt. [9] Then, in November 1834, the Church founded the School of the Elders, which was held in the printing office in Kirtland. [10] During this school, the presiding officers of the Church presented seven discourses on theology that became known as the Lectures on Faith. These were published in the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants and remained in that publication until 1921. [11]

Finally, in February 1835, a historic reorganization in Church government occurred that had a profound effect on missionary work: the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the Quorum of the Seventy were organized. These two quorums were given the primary responsibility of directing missionary work throughout the world. [12]

The greatest number of Latter-day Saints resided in Ohio and Missouri because the Church’s official gathering places were in these states. The statistics are not exact, but historians estimate that there were twelve hundred Saints living in Jackson County when the mobs drove them out in November 1833. [13] From that time until the beginning of 1838, Kirtland probably became the preeminent gathering place and center of missionary activity for the Church. [14] From 1835 to early 1838, the Latter-day Saint population of Kirtland more than doubled, from about nine hundred to two thousand. [15]

For those interested in the early history of the Church in Illinois, the question naturally rises: How did the Mormon population in the state of Illinois compare to the number of Latter-day Saints living in Ohio and Missouri? The Church did not keep official statistics of how many members were living in Illinois in 1835, so we must rely on sources such as missionary reports published in the Messenger and Advocate, county histories, private letters, and journals. These records indicate that there were approximately five hundred Latter-day Saints living in Illinois during 1835. According to the religious statistics published in at least one history, that would have made The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints the fourth largest religious group in Illinois. The only churches with more members were the Methodist Episcopal (15,097), Baptist (7,350), and Presbyterian (2,500). [16] This was a remarkable accomplishment for the Latter-day Saints since their Church had been founded only five years earlier. From 1835 to 1838, missionary activity in Illinois continued to flourish.

Charles C. Rich in Northern Illinois

Perhaps the most noteworthy Latter-day Saint in northern Illinois during the early history of the Church was Charles C. Rich. In late 1832, when he was only twenty-three, Charles had become the leader of a branch in Pleasant Grove, Tazewell County, near Peoria, Illinois. At that time, he had only been a member of the Church for about six months. [17]

In 1834 he had marched in Zion’s Camp but had returned to Pleasant Grove in July of that year and continued as the presiding authority of the branch. In August, Charles baptized his uncle Landon Rich and his uncle’s wife. The ceremony attracted a crowd of about fifty people. Other active members of the Pleasant Grove Branch included Solomon Wixom and Jedediah Owens. Brother Rich also traveled to Crow Creek twice in September and there held meetings in the homes of Jedediah Owens and Tom Hadlock. From 1832 to late 1834, the number of members in Tazewell County increased from seven to about twenty. [18]

During the time Charles labored as branch president, he often left the area to serve short-term missions. From July 1834 to April 1837, when he finally moved to Missouri, Charles was away from home for at least fourteen months preaching the gospel. [19] One of these missions was to the area of the Du Page River about thirty miles from Chicago. Rich’s companion on this mission was Morris Phelps, who had returned to the region as a missionary after moving to Missouri. Phelps had evidently been in the area previously and had baptized a few people. While Elders Rich and Phelps served at Du Page together, they baptized at least four new converts—Father Clark, Wesley Clark, and Ruth and William Naper (sometimes spelled Napier). [20] There were enough new Saints that the missionaries organized a small branch. [21]

On one occasion, the missionaries were teaching in a schoolhouse at Big Woods when an especially contentious individual named Mr. Howe opposed them. This motivated Elder Rich to wash his feet as a testimony against the man. [22] A local history tells of a flood that following spring that humbled the man considerably. Howe had built “a dam and a frame for a saw-mill at the lower end of the island.” Unfortunately, “the dam was carried away in a flood the following Spring.” [23]

During this mission, Elders Rich and Phelps also made a short trip to Chicago but were not warmly received. By 1835, Chicago had a population of a little over three thousand. [24] The elders’ usual pattern was to go to churches or homes and ask permission to preach. However, in Chicago they were denied. Disappointed, they roamed through the streets of the city and spent some time at the harbor. After an unsuccessful, one-day visit to Chicago, they returned to Du Page. Soon thereafter, Phelps departed for Indiana, thus ending their short-term mission. [25] In a letter written to the Messenger and Advocate, Elder Rich summarized their missionary activities with the following report: “I have just returned from the north part of this state, where I have been laboring in company with Elder M. Phelps for a few weeks past. We were opposed by the [non-Mormon] missionaries: but succeeded in establishing a church in Cook co. comprising nine members.” [26] (The Cook County of 1835 included what is now Du Page, Lake, and parts of McHenry, Kane, and Will counties. The area adjacent to the Du Page River was known as the Du Page precinct or district.) [27]

After Rich’s mission to Du Page and Chicago, he returned to his home in Pleasant Grove, where he remained for the next two months. There he worked on his farm and served conscientiously as a branch president. He baptized his Grandmother Rich, and made a few visits to Peoria. Then in September he went on a mission to Adams County, in western Illinois, with his good friend Solomon Wixom. Adams County was outside of Rich’s jurisdiction, so he allowed Wixom to “take the lead” during this mission. [28]

Rich soon returned to Pleasant Grove, where he made plans to travel to Kirtland. He “delivered up the Church into the hands of . . . Jedediah Owen,” and on January 26, 1836, he departed with Levi Tomlin to Ohio. The elders stayed with family and friends and often took the opportunity to preach along the way. Tomlin accompanied Rich to New Albany, Indiana, and then returned to Illinois. Rich proceeded to Kirtland, where he arrived in early April. Here Elder Rich had several remarkable spiritual experiences. Hyrum and John Smith ordained him a high priest, and he received “washings and anointings” in the Kirtland Temple. At this time, Don Carlos Smith, the Prophet’s brother, told Rich “that he would be a mighty man of God.” On another occasion, Rich attended a meeting where he was involved in the ordinance of “washing of the feet.” At the same gathering, there was a tremendous outpouring of the Spirit. Rich recorded in his journal that there were “great manifestations of the power of God. I beheld lights in the room passing back and forward. It was [prophesied] that I should be as mighty a man as ever stood on earth. . . . And I was fill[ed] with the spirit of prophecy.” [29]

During his stay in Kirtland, Charles had the privilege of associating with many of the Church’s leading authorities. He spent many evenings with Hyrum Smith, helping him with his garden and even whitewashing his house. He heard Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, and Sidney Rigdon speak. He also heard Brigham Young sing and speak in tongues. In addition, the Prophet’s father, Joseph Smith Sr., gave Charles a Zion blessing, which was the equivalent of a patriarchal blessing. In this blessing, the patriarch told Charles that he was a descendant of Joseph of Egypt, through his son Ephraim, and that “Satan would have no power over him.” [30] Elder Rich had come to Kirtland to be edified and strengthened, and he was not disappointed. When he returned to Illinois, his faith had crystallized, and his devotion to the Church and its leaders was greater than ever.

Between 1835 and 1838, Charles Rich and many of his Latter-day Saint friends in Illinois moved to Missouri, one of the Church’s principle gathering places. Two of his converts from the Du Page district, Ruth and William Naper, migrated to the settlement of Haun’s Mill in Caldwell County, Missouri. Unfortunately, they became victims of the Haun’s Mill Massacre. William was one of seventeen Latter-day Saints killed at the tragic event. In addition, a few days after the massacre a large company of armed men took possession of Haun’s Mill. Some of them lodged in the Naper home without Ruth’s consent. “One night one of them came to my bed and laid his hand upon me,” recorded Ruth, “which so frightened me that I made quite a noise and crept over the back side of my children, and he offered no further insult at the time.” [31]

The Napers were not the only Latter-day Saints from the Du Page district in Illinois to migrate to Missouri. The extended family of Timothy Baldwin Clark also moved to Zion to be with their relatives, the Morris Phelps family, Clark being the father-in-law of Phelps. [32] In addition, the Pierce Hawley family gathered with the Saints in Missouri at that time.

By the end of 1836, Charles Rich was determined to move to Missouri as well. On October 20 he made a trip to Caldwell County, Missouri, to purchase some land. After shopping around for some time, he finally bought 160 acres of property and then returned to Illinois to prepare for his move. During his final stay in Tazewell County, he worked with his father, performed his Church responsibilities, and finally sold his land. He also helped make arrangements for his grandmother’s funeral, which was held on March 19, 1837. [33]

When Charles moved from Tazewell County, it brought to a close an important chapter in his life. He had done more than anyone else to help the Church prosper in the general region of Peoria, Illinois. While Charles served as branch president in Pleasant Grove, he watched the congregation grow to at least twenty-three members. He also organized a small branch in Crow Creek, where Jedediah Owens presided. [34]

With his move to Missouri, Charles Rich left one of the outlying areas of the Church and spent the rest of his life in “the mainstream of Mormon history.” [35] He eventually followed the Church from Missouri to Nauvoo, Illinois, and then to the Salt Lake Valley. There he became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

In addition to Illinois residents, like Charles Rich, who migrated to Zion, there were also many of the early Latter-day Saints who merely traveled through northern Illinois on their way to or from Missouri. The elders traveling to mission fields in the eastern United States and Canada felt blessed to stay with Latter-day Saint families along the routes they traveled. In fact, a few families were asked to continue living along the major routes and were to “make a home for the Elders” as they traveled. Isaac Snyder continued to live near the border of Illinois and Indiana to provide shelter for the migrating Mormons. [36] The development of a lake port in Chicago also helped members who traveled by way of Lake Michigan.

When the migrating Saints heard stories about the mistreatment of Latter-day Saints in Missouri, some of them chose to settle in Illinois, at least temporarily, until conditions improved in Zion. A few of them settled in a little community in Will County, Illinois, called Twelve Mile Grove. The posterity of Sarah Shannon Leavitt is an example. A widow for twenty years, Sister Leavitt came from Canada with her five children. As the years went by, Sister Leavitt’s children married into other families in the community. These families helped build the first school in the community. Two of Sister Leavitt’s granddaughters were the first teachers at the school, according to The History of Will County. [37] We have no record of what happened to some of these families, but we do know that members of the Leavitt family eventually joined the Saints in Nauvoo, Illinois. [38]

Edward Partridge and Thomas B. Marsh in Central Illinois

Two of the most prominent Latter-day Saints to serve missions in central Illinois during 1835 were Edward Partridge and Thomas B. Marsh. The Prophet Joseph Smith had called Partridge to be the first bishop of the Church, and since 1831 Edward had been serving in that calling in Missouri. [39] Thomas B. Marsh, one of the earliest converts to the Church, moved from Ohio to Missouri in 1832, and by 1834 he was serving on the stake high council in Clay County. [40]

These two elders departed on a mission from Clay County, Missouri, on January 27, 1835. Their destination was Kirtland, and they planned to preach the gospel along the way. [41] Bishop Partridge gave an overview of their missionary activities with the following journal entry: “We traveled in Missouri 253 miles, and held twelve meetings, traveled in Illinois 235 miles and held thirteen meetings, traveled in Indiana 162 miles, and held eighteen meetings, one conference and one court, and traveled in Ohio 267 miles and held five meetings. Our mission lasted about three months.” Partridge continued: “Although we baptised none, I believe that we were instrumental in removing much prejudice from the minds of the people, and that the seed sown by us will eventually produce some fruit.” [42]

Bishop Partridge’s journal also indicated that the two missionaries traveled without purse or scrip and were treated agreeably by some and unpleasantly by others: “We started without money, but had some given to us on the road and spent all about $4.00. We were turned out of doors once after sunset by a Baptist by the name of Grual. . . . We met with many who received us very kindly and entertained us like brethren; some, however, treated us with coldness and indifference.” [43]

With respect to their activities in Illinois, Bishop Partridge mentioned several places where they preached, including, Rushville (Schuyler County), the village of Sangamon (Sangamon County), Flat Branch (now Christian County), Shelbyville (Shelby County), and at the home of John R. Reed on the Little Vermillion River. While the missionaries were preaching in Flat Branch, they stayed at the home of Brother Evan Obanion. Partridge wrote that the Church had a congregation of sixteen members at Flat Branch. [44] The missionaries also visited Clear Creek (Edgar County). Brother Marsh “preached here 3 years ago,” Partridge recorded, “and feeling that his work was not done when he left . . . thought it his duty to preach again to these people.” [45]

Although no converts were made during this mission, it provided the background for one of the most important occurrences in the life of Thomas B. Marsh. On April 25, 1835, Partridge and Marsh ended their missionary journey in Kirtland. [46] At that time, Elder Marsh learned that he had been called to serve as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. [47] During the next ten days, Elder Marsh’s life was transformed, in whirlwind fashion, as he was suddenly thrust into a position of high leadership in the Church. On April 26, the day after Elder Marsh arrived in Kirtland, Oliver Cowdery ordained him an Apostle. Six days later, on May 2, Joseph Smith designated Elder Marsh President of the Quorum. Then, two days after that, Elder Marsh departed with the rest of the Twelve on a mission to the eastern states. [48]

The Mormon War

Not long after the mission of Partridge and Marsh to central Illinois, antagonists against the Church began persecuting the Latter-day Saints. Specifically, there was an incident that took place in Ash Grove, Shelby County, in 1836–37 that the old-timers referred to as the “Mormon War.” Latter-day Saints had lived in Ash Grove since 1832 or 1833. Hyrum Smith had reportedly preached in the community at the home of John Price at about that time. Other elders followed, and approximately thirty people had joined the Church. [49]

As the Latter-day Saint population grew in the community, hostility also began to increase. Circumstances got out of control when a missionary named Elder Carter was preaching in the home of Allen Weeks. Suddenly a mob from Wabash Point, led by a Methodist minister, advanced upon the Weeks residence, determined to assault the young missionary. Carter was able to elude the mob, and soon Younger Green, a local citizen who was a Latter-day Saint, appeared before circuit judge Sidney Breeze and “swore out a warrant for the leading members of the mob.”

The judge placed the warrant in the hands of Colonel James Vaughn of the militia, who was also a Baptist minister, since it was supposed that the mob would resist civil authority. Vaughn assembled a militia of about one hundred men and started after the mob, which had by this time gathered in a grove of trees. The colonel sent three of his men to tell the mob that if they did not give themselves up they would be taken into custody by force. The members of the mob refused to surrender and countered by saying they would yield only to civil authority. Infuriated, the colonel then tried to rally his men by saying, “I will take them in short order if the majority of this company is willing. All who are in favor of marching upon this mob who defy the laws of Illinois, march to the front ten paces.” To his disgust, only two men stepped forward, while the rest laughed. Colonel Vaughn then left the scene, and the local constable eventually served the warrant, after which the mob and militia purchased some whisky and celebrated. The case never came to trial, and within a short time, according to a local history, “the Mormons ceased to bother the community.” [50] Thus the so-called Mormon War came to an end.

Growth in Church membership in central Illinois from 1835 to 1838 is interesting to observe. By this time, missionaries were traveling across the prairies with some degree of regularity. In fact, the elders were then teaching in nearly every county in Illinois (as they then existed).

Messenger and Advocate

As the missionaries preached throughout Illinois, they often wrote to the Church periodical the Messenger and Advocate to report the results of their labors. Likewise, new members living in isolated areas would sometimes write to this magazine requesting that the Church send missionaries to their community in order to bring more converts into the fold. For example, William Berry wrote from Canton, Fulton County, Illinois, on June 16, 1835, requesting elders, “if they pass[ed] that way, to call and help them onward in the cause of truth.” [51] Three days later, Elder Levi Jackman wrote from Paris (Edgar County), reporting that he and Elder Caleb Baldwin had “baptized five more since he wrote last.” [52] Then on July 7, 1835, Elder Jackman wrote from Clear Creek (Edgar County) that he and Elder Baldwin had established a branch in the area “composed of twenty members in good standing, faith and fellowship.” Jackman then explained: “However, they are young and inexperienced in the work of the Lord, and are unacquainted with the devices of the adversary of the souls of the children of men. . . . Therefore, pray for them, that they may stand, and not be moved, when the hour of temptation comes.” [53]

Another missionary who served in central Illinois who reported his activities to the Messenger and Advocate was Solomon Wixom. In the February 1836 edition of the periodical, Wixom wrote from Crooked Creek (Schuyler County): “The work of the Lord is still gaining influence in this place. I have baptized 9 since I last wrote. The church in this place numbers 18 in good standing.” [54]

Thus the Messenger and Advocate served as a lifeline of communication and a source of inspiration to scattered missionaries and Saints not only in Illinois but also throughout the United States. The periodical has also become an excellent storehouse of information for historians who are interested in missionary work and the growth of the Church during the 1830s.

George Burket in Southern Illinois

Along with Church periodicals, the journals and diaries of early Latter-day Saints contain valuable information to help scholars piece together the history of the Church. Historians often rely on the diaries of Church leaders for information. However, the journals of lesser-known members often contain helpful information as well. President Brigham Young once gave a tribute to the ordinary but faithful Latter-day Saints: “These men know that ‘Mormonism’ is true, they have moved steadily forward, and have not sought to become noted characters as many have; but, unseen as it were, they have maintained their footing steadily in the right path. . . . They are found continually attending to their own business.” President Young continued: “You will find that their lives throughout have been well spent, full of faith, hope, charity, and good works, as far as they have had the ability. These are the ones who will win the race, conquer in the battle, and obtain the peace and righteousness of eternity.” [55]

One of these lesser-known but diligent members who kept a diary was George Burket. We know little about his life other than that he served a faithful mission in southern Illinois from January to March in 1836. Burket’s diary does not contain fascinating illustrations or captivating commentary like the Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, it is still important because it provides us with details about the early Church in southern Illinois that we would not otherwise know.

George Burket began his mission in southern Illinois in late January 1836. On February 2, he taught the gospel in the home of William Galliger. On February 12, he labored in Washington County, “preached 4 times and held one conference.” [56] During this same time, he blessed ten children in the Caws Branch. [57] Then from February 12 to February 20, Burket preached eight times in St. Clair and Washington counties and baptized four people. On February 20, he ordained Cas W. Case as an elder. [58] In addition, he wrote of visiting the family of John Pea. [59]

In early March, Burket held a meeting at the Nelson home. Soon thereafter, he baptized Edmond Nelson and blessed four of his children. Then, on March 11, Burket preached to a small congregation in the home of Brother Younger. Finally, on Sunday, the diligent missionary spoke to an even larger audience in the same home. [60]

While Elder Burket was working in southern Illinois, he decided to take a trip to Church headquarters in Kirtland. When members in that part of the country heard that Burket was going to go to Kirtland, some of them sent money with him to Church headquarters. Burket recorded the following donations: Edmund Nelson ($5.00), William Galagher ($1.00), David Galagher ($5.00), Absolum Free ($1.00), and Hyrum Nelson ($5.00). [61] In late February, Elder Burket started on his journey to Kirtland. Along the way, he visited McLeansboro in Hamilton County, Illinois. About one mile east of there, he found fifty brethren in the area. [62] From there he made his way to Kirtland.

George Burket, then, is representative of hundreds of lesser-known Latter-day Saints who faithfully served missions for the Church in the late 1830s. Specifically, from the years 1835 to 1838, at least 232 Latter-day Saints served missions for the Church, mostly in the United States. [63] Unfortunately, many of them did not keep a journal of their labors. We are therefore grateful for elders like George Burket who conscientiously recorded the details of their activities, thus providing historians with insights into the lives of early nineteenth-century missionaries.

About the time George Burket was traveling east to Kirtland, some of the members of the Church in southern Illinois were deciding to migrate west in order to gather with the Saints in the Latter-day Zion of Missouri. Although John Woodland and his family had been baptized in 1835, they remained in Edward County, Illinois, until 1836, perhaps waiting for the birth of their tenth child. They then traveled to Missouri, settling in a part of Davies County that would become Adam-ondi-Ahman, a site that had been revealed to Woodland in a vision. [64] Another southern Illinois family that migrated to Zion in the late 1830s was that of George Averett. Some of those who made the trek with him were his brother-in-law S. A. Kelsey and Averett’s brothers and sister—Elijah, Elisha, and Eliza. In 1837, George’s parents and other members of the family followed. [65]

By early 1838, however, this migration to Missouri through Illinois increased dramatically. Distressing financial problems, as well as the shameful defection of several Church leaders, led to a “great apostasy” in Kirtland. As a result, Joseph Smith and hundreds of faithful Latter-day Saints fled Kirtland and travelled along the Mormon thoroughfare of Illinois in order to seek refuge with the Saints in Missouri.

Notes

[1] See Arnold K. Garr, “Early Missionary Journeys in North America,” Historical Atlas of Mormonism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 31. Note that in 1835 Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin had not yet been admitted to the Union as states (see John Mack Faragher, ed., The American Heritage Encyclopedia of American History [New York: Henry Holt, 1998], 1066–67).

[2] Deseret News 2004 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret Morning News, 2004), 583. See also Gorden Irving, “Numeric Strength and Geographic Distribution of LDS Missionary Force, 1830–1974,” Task Papers in LDS History (Salt Lake City: Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1975), 9. Irving’s totals are slightly different than the Church Almanac. He has 73 instead of 72 missionaries set apart in 1832 and 108 instead of 111 in 1834. He also had 80 instead of 84 for the year 1835.

[3] Deseret News 2004 Church Almanac, 414.

[4] Deseret News 2004 Church Almanac, 580.

[5] Clark V. Johnson, “Evening and the Morning Star, The,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 347–48.

[6] Andrew H. Hedges, “Messenger and Advocate, Latter-day Saints,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 738–39.

[7] Lyndon W. Cook, “Liahona the Elders’ Journal,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 327–28.

[8] Keith W. Perkins, “School of the Prophets,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1077–78.

[9] Clark V. Johnson, “School in Zion,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1076.

[10] C. Robert Line, “School of the Elders,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1076–77.

[11] Larry E. Dahl, “Lectures on Faith,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 649–50.

[12] See Garr, “Early Missionary Journeys in North America,” 30.

[13] Max H. Parkin, “Jackson County, Missouri,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 564–65.

[14] Davis Bitton, “Kirtland as a Center of Missionary Activity 1830–1838,” BYU Studies 11, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 502.

[15] Milton V. Backman Jr., The Heavens Resound: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Ohio, 1830–1838 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 140.

[16] Illinois in 1837 (Philadelphia: S. Augustus Mitchell, 1837), 62. The statistics provided were for the year 1835, even though the book was titled Illinois in 1837. This book does not have accurate statistics for the Mormons. It simply states that there were “a few throughout the state.”

[17] Leonard J. Arrington, Charles C. Rich (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 22–23.

[18] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 45–46.

[19] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 46.

[20] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 48.

[21] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 48.

[22] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 48.

[23] The Past and Present of Kane County (Chicago: William Le Baron Jr., 1878), 300.

[24] History of Chicago, Illinois (Chicago: Munsell, 1895), 95.

[25] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 49–50.

[26] Messenger and Advocate, August 1835, 166.

[27] Milo Quaiffe, Chicago’s Highways Old and New (Chicago: D. F. Keller, 1923), 57.

[28] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 49.

[29] Quoted in Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 50–51.

[30] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 51–52.

[31] Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 506.

[32] Mary A. Phelps Rich, Autobiography, Church Archives, n.p.

[33] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 52–53.

[34] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 53.

[35] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 53.

[36] Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1904), 4:581.

[37] The History of Will County (Chicago: William Le Baron Jr., 1878), 627.

[38] The History of Will County, 627–28.

[39] Craig Foster, “Partridge, Edward,” in Encyclopedia of Latter Day Saint Church History, 897.

[40] A. Gary Anderson, “Thomas B. Marsh: The Preparation and Conversion of the Emerging Apostle,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: New York, ed. Larry C. Porter, Milton V. Backman Jr., and Susan Easton Black (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1992), 140, 142.

[41] Anderson, “Thomas B. Marsh,” 143.

[42] Journal of Edward Partridge, quoted in Anderson, “Thomas B. Marsh,” 143.

[43] Journal of Edward Partridge, quoted in Anderson, “Thomas B. Marsh,” 143.

[44] Journal of Bishop Edward Partridge, Church Archives, March 9, 1835.

[45] Journal of Bishop Edward Partridge, Church Archives, March 20, 1835.

[46] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1965), 2:193.

[47] Thomas Marsh, “History of Thomas Baldwin Marsh [by himself],” The Latter-day Saints Millennial Star 26 (1864): 391. In this biographical sketch, Marsh wrote, “I proceeded to Kirtland, where we arrived early In the Spring, when I learned I had been chosen one of the twelve apostles.” A. Gary Anderson wrote that Marsh “learned by mail” while “still engaged in [his] mission,” but he does not give a source for his information (“Thomas B. Marsh,” 143). Susan Easton Black wrote that Marsh “learned by mail of his appointment to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.” She cites as her source Journal History, April 25, 1835. However, the Journal History of that date does not say that Marsh learned of his calling by mail. It simply states that he arrived at Kirtland on April 25, 1835 (see Who’s Who in the Doctrine and Covenants [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997], 187).

[48] Smith, History of the Church, 2:194, 219, 222; see also “History of Thomas Baldwin Marsh,” 391.

[49] Bulah Gordon, Here and There in Shelby County (Shelby County: Shelby County Historical and Genealogical Society, 1973), 52.

[50] Gordon, Here and There in Shelby County, 52–53.

[51] Messenger and Advocate, July 1835, 160.

[52] Messenger and Advocate, July 1835, 160.

[53] Messenger and Advocate, September 1835, 185.

[54] Messenger and Advocate, February 1836, 263.

[55] Brigham Young, Discourses of Brigham Young, comp. John A. Widtsoe (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1925), 356.

[56] George Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, Church Archives, 55; hereafter George Burket.

[57] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 31.

[58] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 56.

[59] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 54.

[60] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 55–57.

[61] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 31–32.

[62] Burket, Autobiographical Sketch, 11.

[63] Deseret News 2004 Church Almanac, 583.

[64] John Woodland and Celia Steepleford, Biographical Sketch, Church Archives, 2, 3, 5.

[65] George Washington Averett, Autobiography, Church Archives, 118.