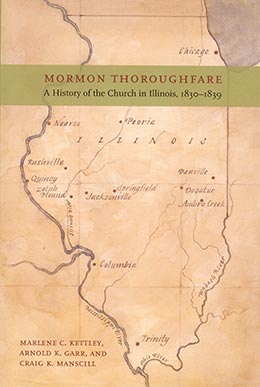

Missionaries and Converts in Illinois 1831–34

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill, “Missionaries and Converts in Illinois, 1831–34,” in Mormon Thoroughfare: A History of the Church in Illinois, 1830–39 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 31–42.

Marlene C. Kettley was a researcher and historian, Arnold K. Garr was chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

On August 13, 1831, Joseph Smith and his companions were traveling from Independence to Kirtland. While they were on the banks of the Missouri River at Chariton, Missouri, they met several missionaries who were traveling the opposite direction, from Ohio (see D&C 62, section heading). This incident symbolizes the geographic complexities associated with Church administration and missionary work at that time. There were actually two centers of the Church in 1831—one in Independence (Zion) and the other in Kirtland. These two communities were approximately nine hundred miles apart, and Church leaders, missionaries, and members frequently traveled back and forth between them, sometimes even running into each other. Illinois, situated nearly halfway between these two communities, served as a great thoroughfare amidst the two principal gathering places. As a result, in the 1830s, scores of missionaries preached the gospel in Illinois, and hundreds of people joined the Church. The purpose of this chapter is to give an account of some of the earliest incidents of conversion throughout the state, between the years 1831 and 1834.

Northern Illinois

The state of Illinois had been organized in 1818, with much of it having been recently ceded by Native Americans. By 1830 the state had reached a population of 157,447, “confined mostly to the borders of rivers and creeks and woodlands.” [1] In the early 1830s, northern Illinois was sparsely settled. If the state were to be divided into three regions—northern, central and southern—the northern part of the state would have had the smallest population. In 1830 only nine “white settlements” were recorded in the northern part of the state. These were Galena, Dixon’s Ford, Hickory Creek, Walker’s Grove (a mission, now Plainfield), Peoria, Pekin, Mackinaw (a little east of Peoria), Buffalo Grove (near present Ottawa), and Bourbonnais. [2] Settlers also lived outside these communities in relatively isolated areas. In 1831 the northernmost part of present-day Illinois was still inhabited by Native Americans, with the exception of the twenty-mile-wide strip, running between Lake Michigan and the Illinois River. This land had been purchased from Native Americans in 1831–32 for the building of a canal between these two bodies of water. [3]

Even though northern Illinois was the least populated region in the state during the early 1830s, it was the area where Latter-day Saint missionaries probably experienced their earliest success. As previously discussed, the first baptism in Illinois probably took place in the northeastern part of the state when Lyman Wight and John Corrill baptized James Emmett. Soon thereafter, the same missionaries also baptized Sanford Porter and James Sumner. These early conversions set in motion a chain of several more baptisms.

After Elders Wight and Corrill baptized Porter and Sumner, they also ordained them elders and admonished them to preach and baptize together. Faithful to their charge, Elders Porter and Sumner traveled northeast to the area of Du Page, about thirty miles from Chicago, to visit Porter’s good friend Morris Phelps. [4] Morris was the man who first told Porter about the Latter-day Saints when Morris was visiting Porter earlier in the summer. Elders Sumner and Porter taught the gospel to Morris and Laura Phelps. In addition, they taught John Cooper and his wife, as well as many others. The missionaries baptized Morris Phelps in August 1831 and several others that same summer. There were enough new converts that the elders organized a small branch in the area. [5] This was probably the first Latter-day Saint branch organized in Illinois.

During this same time, a few others joined the Church in Hickory Creek, a small settlement that would have been within the boundaries of present-day Will County. Although there are few details concerning these conversions, the History of Will County asserts, “The Mormons were the first who preached in the settlement, and used to promulgate their heavenly revelations as early as 1831, and next after them came the Methodists.” The history states that a Mr. Berry “turned Mormon” but gives no other information concerning his conversion. [6]

Other than that, there are only scattered fragments of information about converts during the year 1831. Sanford Porter’s son, Nathan, wrote in his journal about a man named William Aldrage (perhaps Aldridge or Aldrich) who joined the Church. His two sons, John and Harrison, were also baptized. However, Porter does not give the name of the county in which the family lived. [7]

Thus the restored gospel of Jesus Christ had been introduced to northern Illinois. These early converts were but the first of many who would embrace the gospel. The Journal History of the Church states that there were twenty-five Latter-day Saints living in Illinois in the year 1831. [8] If this is an accurate figure, all the members were probably living in the northern part of the state. The Journal History also indicates that there were no Latter-day Saint branches in Illinois as of December 31, 1831. [9] However, there was one, possibly two, short-lived branches in the state that existed during the summer and fall of 1831. Nathan Porter claims that his father, Sanford, organized the Du Page Branch at the Morris Phelps home. [10] The Coopers, Phelps, and others probably attended church there. A second branch was organized in 1831 or 1832 at Pleasant Grove in Tazewell County. One local history maintains it was “the first church organization” in the county. [11] The Porters and Sumners very likely attended this branch.

These two branches had such a short history because of the doctrine of gathering. On July 20, 1831, Joseph Smith received a revelation which designated Missouri as a place of gathering for the Saints, with Independence as the “City of Zion” and the “Center Place” (D&C 57:1–3). After this revelation, many members of the Church began to migrate to Missouri, including several of the early converts in northern Illinois. By October 14, 1831, Morris Phelps had “sold his possessions in Illinois and started for Jackson county, [Missouri].” He arrived March 6, 1832. [12]

The birth of a baby caused Sanford Porter to leave two months later than the Phelps family, in December 1831. His company included the Emmett, Aldridge, and Berry families. Because they left so late in the year, they experienced a cold, arduous journey. One account speaks of frost and snow encircling their campfires. However they persevered and eventually arrived at Independence in March 1832. “Like Israel of old,” they believed they were “on concecrated [sic] land.” [13]

The Conversion of Charles C. Rich

While some Latter-day Saints chose to migrate to Missouri, other members of the Church decided to stay in northern Illinois, at least for a few more years. Perhaps the most prominent member who remained in Illinois during the early 1830s was Charles C. Rich. Lyman Wight and John Corrill first introduced the gospel to Rich in 1831 when they were preaching in Tazewell County. The missionaries baptized Rich’s friend, Sanford Porter, but Charles did not join at that time. The elders were only in the area for a few days and then traveled on to Missouri. Even though Charles was not baptized on that occasion, he believed what the elders taught him. The missionaries also gave him a copy of the Book of Mormon, which he “read and advocated.” [14]

A year later, two new missionaries, George M. Hinkle and David Cathcart, came to Tazewell County. This time Charles was ready. During the first lesson, the elders told Charles and other members of his family to repent and be baptized “in order to receive the Holy Spirit.” Otherwise they would have “no claims upon the Lord for His Spirit.” The investigator heeded the warning and on April 1, 1832, Elder Hinkle baptized Charles Rich, along with his parents, Joseph and Nancy, and his sixteen-year-old sister, Minerva. Soon thereafter, others were baptized in the area and a small branch was organized. [15] Charles became a pillar of strength for the Church in northern Illinois, and eventually he would be called to serve in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

The Black Hawk War

Shortly after Charles joined the Church, the Black Hawk War broke out in northern Illinois. This dreadful conflict wreaked havoc upon the region and was a turning point in the history of the state. The background to this war began in 1831 when the federal government moved the Native Americans in northern Illinois west of the Mississippi River. Soon these Indians began to suffer from hunger because their new land was less fertile than the property they had lived on in Illinois. As a result, in the spring of 1832 Chief Black Hawk led a group of Sak and Fox Indians back to Illinois to plant crops on their former homeland. Unfortunately, a poorly disciplined white militia opened fire on the Indians, and on April 6, 1832, a bloody conflict commenced. [16]

The war terrified citizens throughout northern Illinois. “The panic that had arisen in Illinois at news of Indians’ first coming was as nothing compared to that which now swept over the state,” wrote one historian. “Everywhere on the frontier homes were hurriedly deserted, while families and whole settlements scuttled to forts.” [17] These fortifications were often crowded, noisy, and unsanitary.

Several Latter-day Saint families were also affected by the war, including the Hawleys, Clarkes, and Coopers. Timothy Clarke and his sons, Barrett and William, appear on the “Muster Roll of a company of mounted volunteers . . . in defence of the northern Frontier of the State of Illinois.” Other Latter-day Saints who fought in the war were John Cooper and Pierce (sometimes Perez) Hawley. [18]

On May 24, 1832, Indians killed Aaron Hawley (Pierce’s brother) near the Rock River, four miles south of Kellogg’s Grove. Three of Aaron’s companions were also murdered. [19] Throughout the state, men volunteered to fight in the conflict. In Sangamon County Abraham Lincoln enlisted, and his fellow militiamen elected him as their captain. [20]

Within a few months, the United States Military had forced the Indians into submission. The final conflict ended on August 2, 1832, at the Battle of the Bad Axe where Chief Black Hawk met overwhelming defeat. Lieutenant Jefferson Davis took Black Hawk as a prisoner and transported him to Fort Crawford in Wisconsin. [21] Eventually the chief was placed in irons and put on a steamship for St. Louis. As the boat traveled outward, Black Hawk watched his ancestral lands pass from view. He sadly declared, “I reflected upon the ingratitude of the whites when I saw their houses, rich harvests and everything desirable round them, and recalled that all this land had been ours.” [22]

Regardless of whether the Black Hawk War was just or unjust, the most significant result of the conflict was that the Native Americans involved were expelled from Illinois. This sent a signal to the whites living in the East that it was now safe to live on the Illinois frontier. As a result, settlers began to pour into the state in order to farm its fertile soil. [23]

Parley P. Pratt and William E. McLellin in Central Illinois

At the beginning of this population boom, two elders, Parley P. Pratt and William E. McLellin, served an important two-month mission in central Illinois. Fortunately, each elder wrote a rather extensive account of their missionary activities. McLellin kept a daily journal, and Pratt wrote an eight-page narrative in his autobiography about some of their experiences. Their writings help us better understand the methods and patterns of early nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint missionaries.

They left Independence, Missouri, on January 28, 1833. McLellin wrote, “We determined to keep all the commandments of God: Consequently we had taken no money neither two coats.” [24] This statement indicated that the elders were serious about following the scriptural passages which admonish Jesus’s disciples to travel without purse or scrip (see Matthew 10:9–10; Luke 10:4; D&C 24:18; 84:78). The two missionaries labored in Missouri for over a month without any baptisms. Then on March 9, 1833, they crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois. They spent a few days traveling east through Calhoun County, preaching along the way. Finally, the elders came to Greene County, Illinois, a region where they would experience a considerable amount of success over the next several weeks.

The missionaries made a great number of friends in Greene County. Ironically, one of the most supportive friends was John Russell, a Baptist minister from Bluff Dale (changed to Bluffdale in 1892), Illinois. Russell was one of the earliest settlers in Greene County and is credited with giving Bluff Dale its name. In addition to being a Baptist preacher, Russell was also an educator, writer, and postmaster. [25] On March 16, he heard Elders Pratt and McLellin preach to an attentive audience in a crowded home owned by a Mr. Daton. [26] Pratt maintained that Russell was so impressed with what he heard that he invited the missionaries to remain “in the neighborhood and continue to preach.” Russell even requested that the elders stay at his home. Pratt then recorded: “We tarried in the neighborhood some two months, and preached daily in all that region to vast multitudes, both in town and country, in the grove, and in school houses, barns and dwellings.” [27]

Unfortunately, while the missionaries were working in the area they also encountered opposition. Probably the most persistent antagonist in the county was Reverend Elizah Dodson, a Baptist minister from Carrollton, Illinois. He “continually and openly opposed the remarks of McLellin and Parley Pratt” while they were preaching in Greene County, especially when they were near Carrollton. [28]

William McLellin’s journal gives a literary picture of the elders’ daily activities and mode of operation. From March 16 to May 6, they preached on at least thirty-four occasions (McLellin calls them appointments). [29] Most of the time, both elders would speak. Typically the first missionary would talk for about an hour and a half, and the second elder would limit his remarks to less than an hour. Elder Pratt was the lead speaker on at least twenty occasions, while Elder McLellin spoke first at twelve of their appointments. (Sometimes McLellin would not indicate which elder spoke first.)

The missionaries were such charismatic speakers that they soon began to attract rather large audiences. On Saturday, March 23, they spoke at a schoolhouse so full that some people “could not get in.” Elder Pratt spoke for an hour and fifteen minutes and Elder McLellin for about a quarter of an hour. [30]

Word of their preaching continued to spread rapidly throughout the region. On Sunday, March 31, they spoke to a group of two to three hundred people at the schoolhouse. Elder Pratt invited anyone in the audience who felt impressed to come forward and be baptized. Nobody accepted the invitation at that time, but many of them returned to a second meeting held later that evening. At that gathering, Elder McLellin asked all those who believed the things the missionaries taught “to manifest it by rising up to their feet.” He recorded that “about 30 men & women immediately & unhesitatingly arose.” However, they wanted to investigate the gospel a little longer before committing to baptism. The missionaries announced to the congregation that they would not leave the area for a while, and most of the audience rose to their feet, signifying that they wanted the elders to stay. Of course, this was alarming to Reverend Dodson, who was in attendance at the meeting. Therefore, Dodson and one of his followers rose to speak in an attempt to oppose the missionaries, “but the people immediately began to go out and leave them.” [31] Dodson became so frustrated that he wrote Reverend J. M. Peck, a Baptist minister in Rock Springs, Illinois, to come to Greene County and help counteract the influence of these missionaries. According to Parley P. Pratt, “Peck was a man of note, as one of the early settlers of Illinois, and one of the first missionaries. He had labored for many years in that new country and in Missouri, and was now Editor of a paper devoted to Baptist principles.” [32]

Peck arrived in Greene County around April 14 but was no more successful against the elders than Dodson had been. On Sunday evening, April 14, Reverend Peck spoke to a small congregation for about an hour and forty-five minutes. The purpose of his sermon was to disprove the Book of Mormon. Elders Pratt and McLellin were in attendance and claimed the minister made “a feeble effort,” especially coming from such a learned man. When the meeting was breaking up, Elder McLellin invited those in attendance to come and hear Elder Pratt and himself speak the following night. He even announced that they expected to perform some baptisms and that some of them would probably be “good Baptist people.” McLellin wrote, “This made their Priests stare I assure you.” [33]

The next evening the missionaries did hold their meeting in a home, and six ministers were in the audience, including Reverend Peck. Elder McLellin spoke for about an hour and fifteen minutes and claimed not to be intimidated by the non-Mormon clergymen in attendance. He said that Peck sat right next to him “and took notes and sneered and whispered to one of his fellow priests,” but it did not seem to affect the missionaries. Parley P. Pratt also spoke for a short time, and then the elders asked those who were interested in being baptized to “manifest it.” Three people volunteered—Aaron Holden, James White, and Sophia White. The missionaries walked with their investigators for about a mile to some water and then baptized them. “After Sister White was ready to go into the water Mr Peck hailed her as a Sister and urged her to not throw herself away or out of the church of Christ, as he called it. But she stemmed the [torrent] and went forward with her husband and was baptized.” [34]

These were the first three people to join the Church in Greene County, but more were to come during the next three weeks. On Sunday, April 21, at 11:00 a.m., the elders held a service at the Gateses’ barn, and about three hundred people were in attendance. Once again Reverend Peck was in the audience, only to witness two more people convert to the Church. Elders Pratt and McLellin spoke for about two and a half hours and then walked to a nearby creek and baptized Susannah Campbell and Elizabeth Reed. This infuriated Reverend Peck, who then took his turn speaking in the barn that afternoon. His sermon turned out to be a mean-spirited attack. According to McLellin, Peck’s talk was filled with “loud assertions, abusive language, exaggerations, missrepresentations and . . . many false reports.” The reverend even compared the Book of Mormon to Sinbad the Sailor, Tom Thumb, and Jack the Giant Killer. Peck became so frustrated that he announced to the audience that he was going to leave town the next morning. In response to his announcement, one person in the congregation uttered a loud amen “in token of his joy that [Peck] was going.” [35] The reverend’s hope of counteracting the influence of the Latter-day Saints evidently ended in extreme disappointment. He returned to his home in Rock Springs after staying in Greene County for a little over a week.

On the other hand, the missionaries would baptize several more people in the area during the next two weeks. On Tuesday, April 23, the elders walked about nine miles and preached for approximately three hours. Without writing any more details about the day’s activities, McLellin simply recorded that they baptized two ladies—Mandana Campbell and Mary Ann Clark. [36]

On Wednesday, May 1, the missionaries had an appointment at the home of a Mr. Bellew, where “quite a number” gathered to hear them teach. Elder McLellin spoke for three hours, and then they “went to the creek” and baptized Levi Merick and one other person, probably his wife. [37] These people had been members of the Baptist Church all of their lives.

Two days later, the missionaries held a meeting at the home of a Mr. Watson. Here Elder Pratt spoke for two hours on the restitution of all things, and Elder McLellin addressed the group for about twenty minutes on the plan of redemption. After the meeting, Thomas Turney came forward and asked to be baptized. The elders honored his request, and Parley P. Pratt baptized him that evening at eight o’clock. [38]

On Sunday, May 5, Elders McLellin and Pratt conducted their final baptismal service before leaving Greene County. At 10:00 a.m. that day, they held another meeting at the Gateses’ barn. On that occasion, Elder McLellin spoke for about two hours on several topics, including the doctrine of gathering. At the conclusion of his remarks, he asked if there were any in the audience who wanted to be baptized. To his delight, four people immediately arose. Their names were James H. Reed, Joseph Jackson, Katherine Holden, and Nancy Simmons. McLellin invited the congregation to assemble at 3:30 in the afternoon at the creek, where he would perform the baptisms. A “large company” met at the water’s edge to witness the events. It was evidently a moving experience because many of those in attendance were “affected even unto tears.” [39]

Parley P. Pratt summarized the accomplishments of their mission in Greene County with these words: “Hundreds of people were convinced of the truth, but the hearts of many were too much set on the world to obey the gospel; we, therefore, baptized only a few of the people, and organized a small society.” [40] In fact, during the last three weeks of their two-month sojourn in the county, these two elders baptized fourteen people. The missionaries made such an impression on the region that over fifty years later, a local secular history made mention of their activities as follows: “The Mormon revival of 1830 to 1835 is well remembered. These were conducted by Elders McLellan and Parley P. Pratt in the west part of the county. Considerable excitement grew out of these meetings and some converts made.” [41]

There is a smattering of information about other conversions in central Illinois. Elders Elisha Groves and Morris Phelps reported holding forty-one meetings and baptizing sixteen people in Calhoon County in 1834. [42] Later that year, Phelps also served a mission with Charles C. Rich. They “built up 2 branches,” one in Calhoon County and another in Cook County (which is in the northern part of the state). [43]

Southern Illinois

Even though southern Illinois was the most populous part of the state in the early 1830s, it was the area where the missionaries experienced the least success from 1831 to 1834. Nevertheless, there are accounts of a few baptisms in the region. Merrill and Margaret Willis and their son, William, were baptized in Hamilton County in 1834. [44] Thomas and Sarah McBride, along with their children, joined the Church in St. Clair County, although there is conflicting information concerning the date. The McBrides soon moved to Missouri, where they lived first in Ray and then Caldwell County. On October 30, 1838, Thomas McBride was killed at the Haun’s Mill Massacre. [45] Two others that converted in southern Illinois were Thomas Woolsey in Fayette County and Charles Butler in Washington County. [46]

While Latter-day Saint missionaries were preaching the gospel throughout Illinois, persecution against the Church was mounting in Jackson County, Missouri. The Saints were mistreated so badly in that area that they were eventually forced to leave the county. This unfortunate ordeal ultimately led to the organization of Zion’s Camp, the topic of our next chapter.

Notes

[1] William H. Perrin, History of Cass County (Chicago: O.L. Baskin, 1882), 25.

[2] “Indian Villages c. 1830,” a map showing trading posts, white settlements, and missions; in author’s possession.

[3] Augustus Maue, History of Will County, Illinois, 2 vols. (Topeka-Indianapolis: Historical Publishing Company, 1928), 1:428.

[4] Sanford Porter, Reminiscences, 170, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[5] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1901), 1:373; see also Nathan Porter, Reminiscences, 42, Church Archives.

[6] The History of Will County, Illinois (Chicago: William Le Baron Jr., 1878), 503, 497, 261.

[7] Nathan Porter, Reminiscences, 44–45.

[8] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, December 31, 1831, 4, Church Archives.

[9] Journal History, December 31, 1831, 5.

[10] Nathan Porter, Reminiscences, 42.

[11] History of Tazewell County, Illinois (Chicago: Chas. C. Chapman, 1879), 477.

[12] Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:373.

[13] Nathan Porter, Reminiscences, 44, 62.

[14] Leonard J. Arrington, Charles C. Rich: Mormon General and Western Frontiersman (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 17.

[15] Arrington, Charles C. Rich, 17; Ira M. Hinckley baptized Rich (see Smith, History of the Church, 2:507n; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:102.

[16] George Brown Tindall, America: A Narrative History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1988), 1:424–25; John Mack Faragher, ed., The American Heritage Encyclopedia of American History (New York: Henry Holt, 1998), 92.

[17] Theodore Calvin Pease, The Frontier State, 1818–1848 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 164.

[18] Ellen M. Whitney, ed., The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1970), 1:473, 476–77.

[19] Whitney, Black Hawk War, 2:451.

[20] Robert McElroy, Jefferson Davis: The Unreal and the Real (New York: Kraus Reprint, 1969), 25.

[21] McElroy, Jefferson Davis, 28.

[22] McElroy, Jefferson Davis, 30.

[23] Robert P. Sutton, ed., The Prairie State: A Documentary History of Illinois, Colonial Years to 1860 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1976), 243; see also The History of Will County, Illinois, 79.

[24] Jan Shipps and John Welch, eds., The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1994), 89.

[25] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 458.

[26] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 104–5.

[27] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1973), 84.

[28] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 432.

[29] See Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 104–20.

[30] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 108.

[31] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 110.

[32] Pratt, Autobiography, 86.

[33] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 114–15.

[34] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 115.

[35] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 116–17.

[36] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 117.

[37] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 118–19. McLellin’s journal says, “Levi and [Mrs ?] Merick” were baptized.

[38] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 119.

[39] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 119–20.

[40] Pratt, Autobiography, 91.

[41] History of Green and Jersey Counties, Illinois (Springfield, IL: Continental Historical, 1885), 761–62.

[42] Messenger and Advocate, January 1836, 255.

[43] Morris Phelps Journal, 1, Church Archives.

[44] Susan Easton Black, Membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1848 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 46:706–8; see also Frank Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah Pioneers Book, 1913), 1252.

[45] Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:68; Black, Membership, 24:950.

[46] Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:768; Black, Membership, 47:697.