Incorporating Character Education into a BYU Engineering Department

Daniel R. Winder

Daniel R. Winder, “Incorporating Character Education into a BYU Engineering Department,” in Moral Foundations: Standing Firm in a World of Shifting Values, ed. Douglas E. Brinley, Perry W. Carter, and James K. Archibald (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University), 203–18.

Daniel R. Winder was a Church Educational teacher and part-time instructor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. He was also a PhD candidate at Utah State University in instructional technology.

In a high school physics class, I learned that a bridge has two types of forces acting upon its structure: external and internal. These forces are factors in a bridge’s strength, or what is referred to as its integrity. A few years ago, a different sort of integrity was displayed on a bridge not far from here. During the 2002 Salt Lake Olympics, an elderly volunteer was assigned to keep people, including photographers and journalists, off a bridge that Olympic athletes would be passing underneath. This bridge was an ideal location for photographers to snap shots of the athletes. One particularly aggressive photographer tried to persuade the elderly volunteer to allow him to take a few photos by offering her several monetary bribes, beginning at one hundred dollars, then two hundred dollars, then five hundred dollars. However, the volunteer refused all bribes and would not allow the photographer on the bridge. She had given her word. Although her supervisor was not in the area and she could easily have gotten away with allowing the photographer to take a few shots, her integrity was such that it could not be broken by the enticement of money.

Just as a bridge’s integrity is affected by external and internal forces, so is our personal integrity affected by external and internal forces. With the volunteer, the external force pushing on her was the bribe, and the internal force was her personal commitment to keep her word. Although the pressure increased in the form of an external bribe, it was not stronger than the inward force of her integrity. Her internal integrity was not for sale and remained intact.

The story illustrates that the external display of integrity, and character in general, is determined by internal structures. Like a bridge, these internal structures are strengthened by networks of support. These internal support structures take the form of mental, emotional, and spiritual convictions.

Character Education for the Internal Dimensions of Personal Character

A person’s character is measured in behavioral terms by external indicators. For example, the volunteer on the bridge displayed integrity (a behavior) by keeping her word (external indicator) in spite of the pressure from an aggressive reporter. Because outward signs of character are easier to measure, most instructional models for character development have a goal of producing observable virtuous behavior.[1] Although the final goal of character education is virtuous behavior, I propose that this goal falls short of what character education could be. The following conceptual framework suggests that character education’s final product ought to change people’s very nature, not merely their outward behavior. When their very nature is changed for the better, moral behavior follows.

The gospel helps us understand how a person’s nature can be changed. This understanding falls in the spiritual realm rather than in the psychological realm. To claim that the spiritual aspects of a person’s nature fall into the affective realm, as many instructional models do,[2] is like trying to pound a square peg into a round hole. The assumption of many instructional models that acknowledge the spiritual realm is that a person’s spiritual nature or core being is shaped by a mortal temporal perspective or by temporal cognition rather than by an eternal spiritual process. Thus, our framework stems from an understanding that a character education instructional model that divorces itself from God “lacks a philosophical rudder.”[3]

A Conceptual Framework for Character Development Focused on Changing a Person’s Nature

The first three aspects of character development are under mortal control. The fourth aspect is controlled by God, who follows exact and impartial laws in bringing about a change of nature (see fig. 1). As a person uses agency to function in the first three realms, divine grace changes his or her nature. However, God aids in the other three realms as well. When all four aspects are involved, a person’s character changes because his or her core being, or soul, changes. When a person allows God to change his or her eternal perspective, the change remains as long as the person abides by His precepts.

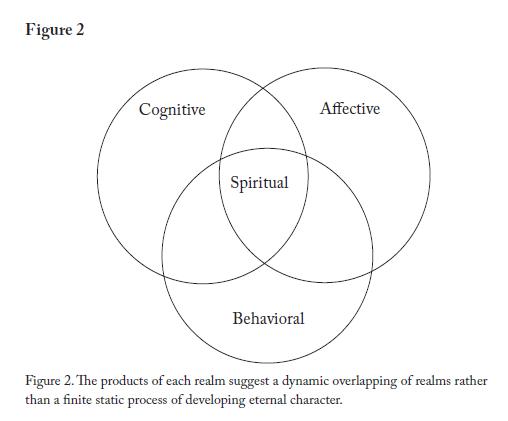

Although figure 1 suggests that changing a person’s nature is a static process of moving information from the head, to the heart, to the life, to the soul of an individual, the process is actually more complementary in nature (see fig. 2). Indeed, the words of modern prophets suggest that cognition, affection, and behavior are all intertwined in spiritual learning.[4]

The Cognitive Aspect

Many cognitive psychologists point out that mental knowledge structures, or schemas, exist in the mind of each individual.[5] These structures aid in understanding new concepts as a person assimilates new knowledge into existing knowledge structures.

If the goal is to cultivate character, an educator must first ensure that the person understands the particular character trait. For example, a person must understand the concept of integrity before living it. This process of understanding is accelerated by discussing a trait in terms of something already familiar to the person. Elder Richard G. Scott gives similar counsel: “As each element of truth is encountered, you must carefully examine it in the light of prior knowledge to determine where it fits. Ponder it; inspect it inside out. Study it from every vantage point to discover hidden meaning. View it in perspective.”[6] For example, an instructor could help a student apprehend integrity by saying, “Integrity is like honesty but . . .” This is particularly applicable to the mental development of character traits that affect one’s spirituality.

When a person mentally understands the concept of a particular character trait, that comprehension can then be translated into moral knowledge. Thomas Likona, a prominent designer of character education instructional models, refers to the “cognitive side of character” as moral knowing and lists the following six aspects: “moral alertness (does the situation at hand involve a moral issue requiring moral judgment?), understanding the virtues and what they require of us in specific situations, perspective taking [knowledge of how one’s actions affect others], moral reasoning [knowledge of how to reason through a moral dilemma], thoughtful decision making [knowledge of to make moral decisions], and moral self-knowledge: all the powers of rational moral thought required for moral maturity.”[7]

The Affective Realm

As powerful as cognition can be, it will be temporary if it is not “in the mind and heart.”[8] For example, Laman and Lemuel failed to move angelic information from mind to heart, from cognition to affection. Their example led Elder F. Melvin Hammond to teach that “information, even from angels, must be taken from the head to the heart of every individual.”[9] Elder Hammond explained that once a teaching is in the heart, it should be “accompanied by the Spirit of Truth and total commitment” to live it.[10] He further instructs gospel instructors to explain and “give as many how to’s as possible” to facilitate this process.[11] How to’s are seen as “procedural knowledge,”[12] or strategies for applying a precept.

Because Laman and Lemuel did not translate information from their minds to their hearts, their behavior during the journey to the promised land was filled with only brief periods of obedience. In fact, their stunning lack of information-processing led Nephi to ask, “How is it that ye have forgotten that ye have seen an angel of the Lord?” (1 Nephi 7:10). The answer may be found in President Brigham Young’s statement: “If you love the truth you can remember it.”[13]

Even when people know and remember moral values, they may still choose not to follow them. As Lickona writes, “People can be very smart about matters of right and wrong, however, and still choose the wrong.”[14] The affective realm constitutes the emotional or feeling realm of character, the desire to be good rather than a simple cognitive understanding about good. As important as it is to incorporate information into one’s existing mental structure, the affective realm merges the gap between understanding and behavior. The Holy Ghost aids in this process of carrying information to the heart. “When a man speaketh by the power of the Holy Ghost,” Nephi explained, “the power of the Holy Ghost carrieth [the message] unto the hearts of the children of men” (2 Nephi 33:1). However, Elder David A. Bednar explains that the Holy Ghost cannot supersede agency: “Please notice how the power of the Spirit carries the message unto but not necessarily into the heart. A teacher can explain, demonstrate, persuade, and testify, and do so with great spiritual power and effectiveness. Ultimately, however, the content of a message and the witness of the Holy Ghost penetrate into the heart only if a receiver allows them to enter.”[15]

Transforming what is known in the mind into what is felt in the heart requires a “tuition of diligence” that “must be paid” to “personally ‘own’ such knowledge.”[16] This is especially true of spiritual truths. For a spiritual truth to enter into our hearts, the learning must transcend “far beyond mere cognitive comprehension.”[17] Agency must be employed by the person seeking to internalize such knowledge. “A student authorizes the Holy Ghost to instruct”[18] related to his or her “willingness to learn and receive instruction from the Holy Ghost.”[19] It “involves the exercise of moral agency . . . and invites the evidence of things not seen from the only true teacher, the Spirit of the Lord.”[20]

By having a willing heart and exercising agency, we move from being able to “answer test questions well” to having truth sink deep into our minds and hearts.[21] Elder Scott said the result of internalizing those principles is that they are “made part of the students’ guidebooks for life.”[22] We can help students internalize truth by asking questions that lead them to “think about doctrine, appreciate it, and understand how to apply it.”[23]

The Book of Mormon contains moving, descriptive examples of individuals who moved information from head to heart. Alma the Younger, for example, remembered his father’s teachings of the Atonement of Jesus Christ and says, “As my mind caught hold upon this thought [cognitive realm], I cried within my heart [affective realm]: O Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy on me” (Alma 36:18). Enos had a similar experience with his father’s words, which had “sunk deep into [his] heart” as his “soul hungered” for “a remission of [his] sins” (Enos 1:2–4). In both examples, the teachings of the gospel from Alma’s and Enos’s fathers needed to enter their hearts before their conversions. The process of changing one’s nature begins when truths in the mind take root in the heart.

Behavioral Aspect

A truth that takes root in the heart influences actions. As the CES handbook explains, “When a person comes to believe in and care about [affective realm] a principle to the point it changes or directs his or her behavior, that principle becomes a value.”[24] Elder Henry B. Eyring explained that values come “from the inner workings of the Spirit as we live gospel principles.”[25] Thus, one learns to live a newly discovered element of God’s character by understanding and caring about divine values to the point of applying them and following the Spirit’s gentle promptings. Acting upon our values therefore “eliminate[s] the void between information and application.”[26]

To influence behavior, a person must know how to live by the eternal character trait. Otherwise, a person may understand and desire to live a divine principle but not actually carry it out.

Lickona’s model of character education helps us understand the bridge between desire and behavior. There is a moral action bridge made up of three aspects of character: “moral competence,” abilities or skills to carry out a moral task; “moral will,” motivation or desire to carry it out; and “moral habit (a reliable inner disposition to respond to situations in a morally good way).”[27] As strategies to implement each of these are learned, behavior corresponds with desire.

The Spiritual Aspect

The spiritual aspect of acquiring character traits is not independent of the other three but is an integral part of all three. As people seek to understand a true precept, the Holy Ghost witnesses unto, not into, their hearts and shows them how to apply it in a behavioral way. This active participation allows agency, and “that use of agency by a student authorizes the Holy Ghost to instruct.”[28]

Nephi explains the role of the Holy Ghost in helping a person learn to live by the words of Christ. He revealed that “the words of Christ will tell” a person what to do, while the Holy Ghost “will show” them what to do (2 Nephi 32:3, 5; emphasis added). For example, an angel told Nephi to obtain the brass plates, yet the Spirit showed him how to obtain them (see 1 Nephi 3, 4). While the words of Christ may teach and model the concepts of character, it is up to the individual, working with the Holy Ghost, to learn strategies to abide by them. For example, we study our scriptures and learn about integrity. Then, as we live our lives, the Holy Ghost helps us apply integrity by gentle promptings. The words of Christ tell; the Holy Ghost shows.

In addition to leading a person to develop character traits, as an individual works with the Holy Ghost, it has a cleansing and sanctifying effect. The Holy Ghost leads us to put “off the natural man and [become] a saint” by understanding and applying the doctrine of the Atonement of Christ (Mosiah 3:19). Ultimately, it is only through our application of the Atonement of Jesus Christ that God changes our nature. C. S. Lewis beautifully illustrates this in his novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. In this story, a boy named Eustace is turned into a dragon as consequence of his nasty, spoiled disposition. After days of restitution and rehabilitation, he is able to peel off the scales of his dragon skin. However, the scales continue to grow back no matter how hard Eustace tries to peel them off. This continues until the Lion, as a symbol of Christ, intervenes. Eustace recounts, “Well, he [the Lion] peeled the beastly stuff right off—just as I thought I’d done it myself the other three times. . . . And there was I as smooth and soft as a peeled switch and smaller than I had been. . . . I’d turned into a boy again.”[29]

In the scriptures, there is no better example of the spiritual process of developing character attributes that change one’s nature than that of King Benjamin’s people. As these people applied the Atonement of Christ, their natures were changed (see Mosiah 5:1–5).

The spiritual aspects of character development are crucial. Any character education instructional model that leaves God out, as mentioned earlier, “lacks a philosophical rudder.”[30] Likewise, any character education model that ignores the spiritual realm or the role of the Redeemer in changing one’s nature ultimately lacks a philosophical engine.

Instructional Strategies for All the Realms

There are several strategies for developing the first realm of character, or the cognitive realm, in students. We must first help students identify what they know is right or good, to acquire what Lickona calls moral knowing. Second, we must help them connect what they know to what they do; for example, ask, how does the principle of honesty relate to the doctrine of being a child of God?[31] Third, we must build on a student’s current understanding. Fourth, we must encourage students to define what they know by asking higher-level questions, such as, how does a moral person think?

Instructional strategies for developing the second aspect, the affective realm, of a person’s character develop what Lickona calls moral feeling, desiring good, and habits of the heart.[32] Indeed, after the cognitive phase of learning truths about character, the only alternatives are obedience or rebellion (see 3 Nephi 6:18). An instructor has little control over the way students choose to respond to truth. Therefore, an effective instructional strategy is to help students understand the role of agency in developing habits of the heart. Also, a teacher can point out that new attitudes are adopted when old ones are surrendered. Ask questions that help a student think about a doctrine, appreciate it, and understand how to apply it. For example, ask, when have you felt the need for integrity and why did you feel it then? These types of questions help students focus on their feelings and why they feel them at various times. The objective is to help people realize what and how a moral person feels. As students move from knowing to desiring, they (1) internalize truth so that they can apply it, (2) develop a willing and teachable heart, (3) think and ponder true principles, (4) love the truth, (5) seek the aid of the Holy Ghost, and (6) use agency to invite the Holy Ghost to carry the truth into their heart.

The third realm of character development focuses on implementing behavior. To live by a truth, one must learn strategies. Thus, instructional strategies for this realm focus on how to’s, or procedural knowledge. For example, a New Era article recommends the following strategies for honesty: “Pray specifically to see the good in yourself, . . . read about people from the scriptures and from good literature who have overcome hardships and emulate their traits,” “counsel with your parents and perhaps your bishop,” “practice being honest,” and “if you slip, . . . quickly correct yourself by saying something like, ‘Excuse me. That wasn’t totally honest. What I meant to say was . . .’ and fill in the blank.”[33]

It should come as no surprise that the instructional strategies for developing the fourth realm of spiritual elements all center around developing faith: faith in God’s power, faith that He will send promptings, and faith that the Lord can change a person’s very nature. Elder Bednar teaches that faith comes from “assurance, action, and evidence”: “assurance leads to action and produces evidence, which further increases assurance.”[34] Teachers can influence students to develop this aspect by encouraging them to experiment by testing prophets’ words as Alma teaches in Alma 32.

Incorporating Character Education into Engineering Departments

Many engineering departments around the country focus on the communal aspects of character education using the strategies outlined in table 1. BYU’s own engineering departments use many of these same helpful strategies to develop the communal aspects of character.

The conceptual framework and strategies provided in this chapter thus far outline tools to encourage students to develop lasting moral character by changing their very natures. These instructional strategies require professors’ conscious effort. The following are nine unobtrusive approaches for engineering instructors to encourage character development. They are adapted from Likona’s comprehensive approach to character development.[35]

The first and most important unobtrusive way to encourage character development in students is through a concerned teacher who is a moral model and moral mentor. Richard Osguthorpe, a character educationalist, explains that “the young acquire virtue by being around virtuous people. That is, virtue is not ‘taught’—at least not in the way that mathematics or biology is taught. Instead, virtue is ‘caught’ or ‘picked-up’ by interacting with those who seemingly possess it.”[36]

A second unobtrusive approach is to ensure that course objectives, instructional activities, and assessments all agree. When these all line up, a student will not have reason to complain about the unfairness of a course and can thus focus on the purpose of the course as well as the virtues of the moral mentor. However, when course objectives, instructional activities, and assessments do not agree, students feel frustrated, blame the professor for their poor performance, and consider an otherwise virtuous professor to be unfair because of an “unfair assessment.”

A third unobtrusive way to encourage character growth is to foster a classroom community—an environment where students are encouraged to cooperate, not to fiercely compete. An instructor who announces that he or she is teaching a class intended to weed people out of the major and that only two-thirds of the students will pass does not encourage communal nor private aspects of character development. In such classes, students hurt their own grades by helping their fellow students. For example, suppose a class is given an assignment to design and develop an airplane out of an aluminum can and only the top five longest flights receive an A grade. A struggling but shy student may approach a successful student and ask, “Can you help me understand . . . ?” Every aspect of the successful student’s internal moral character is now at odds with the external forces imposed by the demands of the class. An otherwise helpful student may brush off the student in need in order to succeed.

A fourth way to encourage character education is to give reasons for your rules and assignments. Students react well when they know that the learning activities will help them succeed. In contrast, an arbitrary assignment with an explanation of “because that is the way it is” can create educational apathy.

A fifth way to encourage character growth is to allow and encourage self-directed learning. If we want students to develop responsibility for their learning, they must be given opportunities to take responsibility for it. How many self-directed learning activities a student needs will be determined by the student’s prior knowledge of the subject. However, an effective strategy with uncharted knowledge is to show students examples of appropriate self-directed learning activities. For example, showing former students’ successful self-directed projects can motivate current students to propose a self-directed learning activity.

A sixth way to unobtrusively encourage character growth is to teach virtues through the curriculum. In engineering, we emphasize the need for precision and truth. This emphasis could be coupled with a short moral story to develop the affective realm and even a few strategies for the behavioral realm. These do not have to be long, drawn-out stories but can be as short as a thirty-second vignette. An example of a short character-building vignette is the bridge story at the beginning of this chapter.

A seventh principle is that great expectations require great support. When professors expect a lot, they must be willing to provide support. For example, returning a paper with a letter grade and no explanation does very little to develop a student’s writing skills. Giving a student a paper with feedback on it does more, and allowing the student to use the feedback to develop the skill does even more. In essence, when professors want to develop character in their students, if they do not have time to care, then they do not have time to teach.

An eighth principle is to encourage ethical reflection. This can be done by asking students, “What is the (moral, ethical, right, wrong) thing to do in this situation?” As students ethically reflect upon relevant issues, they can develop various aspects of character.

A final unobtrusive principle that faculty can employ is to encourage students to cultivate a conscience of craft: a desire to do a good job. Students naturally want to please teachers who care about them. In addition, teachers can help struggling students to succeed rather than just write them off. Teachers who want to develop a conscience of craft in their students must be willing to take the time to give feedback on assignments that are subpar and to help a struggling student measure up.

Conclusion

The results of character education can be more meaningful and lasting when the goal is to change one’s nature rather than to just temporarily change behavior. When people learn truth, love truth, and live truth, their core character becomes more than just moral; it becomes divine in nature.

Nine unobtrusive approaches can cultivate character in an engineering department. These approaches involve the parts of character development that instructors can control. Character can be influenced by instructors, but students must exercise agency to bring moral habits into their hearts. As professors interact with students, they discern where their students need help to fully develop character traits, and they plan instructional activities accordingly. Teachers’ moral and ethical development cannot be ignored and may well be one of the strongest and most effective ways to teach character education.

Focusing on the four aspects of students’ characters—cognitive, affective, behavioral, and spiritual—gives students a moral and spiritual foundation for their very beings, their core natures. This focus helps students at BYU develop the kind of character that President Gordon B. Hinckley desires for BYU graduates: “If this university meets the purpose for which it is maintained, then you must leave here not alone with secular knowledge but, even more important, with a spiritual and moral foundation, . . . to be a man or a woman who will rise above the mediocrity of his or her surroundings and stand up for what is good and decent and right.”[37] This type of character can be developed by developing the internal structures of character that change a person’s very nature.

Sidebar. Ways to Promote Character Education

Following are several ways that engineering departments are promoting character education:

• Teaching about the ethical dilemma through role play or case study: job-related issues (clients), legal issues, boundaries of competency, safety issues, health issues, confidentiality issues, famous cases, conflicts of interest, acknowledging and correcting errors, risks/

• Teaching standards or codes for the profession and how to handle violations.

• Offering specific courses or workshops, usually in ethics education.

• Instructing about research and informed decisions and the role of accuracy in information.

• Focusing on environmental aspects—ask how will this impact the environment?

• Using instructional activities such as essays, readings, and discussions.

• Focusing on teachers as moral models.

• Teaching about the benefits of diversity.

Figure 2.

Notes

[1] See Thomas Lickona, “Character Education: The Cultivation of Virtue,” in Charles M. Reigeluth, ed., Instructional Design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory (Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, 1999), 2:597.

[2] See Barbara L. Martin and Charles M. Reigeluth, “Affective Education and the Affective Domain: Implications for Instructional-Design Theories and Models,” in Reigeluth, Instructional Design Theories and Models, 2:485–509.

[3] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:599.

[4] See Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:599; and David A. Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith” (Address to CES religious educators, Jordan Institute of Religion, West Jordan, UT, February 3, 2006).

[5] See Robert Brien and Nick Eastmond, Cognitive Science and Instruction (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology, 1994), 37–64.

[6] Richard G. Scott, “Acquiring Spiritual Knowledge,” Ensign, November 1993, 86.

[7] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:600.

[8] Richard G. Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth” (Address to CES religious educators, Jordan Institute of Religion, West Jordan, UT, February 4, 2005), 2.

[9] F. Melvin Hammond, “Eliminating the Void between Information and Application” (CES Satellite Training Broadcast, August 2003), 17.

[10] Hammond, “Eliminating the Void,” 17–18.

[11] Hammond, “Eliminating the Void,” 17.

[12] Brien and Eastmond, Cognitive Science and Instruction, 58.

[13] Brigham Young, Discourses of Brigham Young, arr. John A. Widtsoe (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 10.

[14] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:600.

[15] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 1.

[16] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 5.

[17] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 3.

[18] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 3.

[19] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 3.

[20] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 3.

[21] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 2.

[22] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 2–3.

[23] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 6.

[24] Teaching the Gospel: A Handbook for CES Teachers and Leaders (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2001), 6.

[25] Henry B. Eyring, quoted in Teaching the Gospel, 6.

[26] Hammond, “Eliminating the Void,” 17.

[27] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:600.

[28] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 3. See also Richard G. Scott, “Helping Others to be Spiritually Led” (given at the CES Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants and Church History, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, August 11, 1998).

[29] C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 90.

[30] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:599.

[31] See David A. Bednar, “Be Honest,” New Era, October 2005, 4.

[32] Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:599–600.

[33]“Q&A: Questions and Answers,” New Era, November 2006, 14–16.

[34] Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” 2.

[35] See Lickona, “Character Education,” 2:600–606.

[36] Richard Osguthorpe, “Why Do We Want Teachers of Good Disposition and Moral Character?” (paper presented at the annual metting of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, New York, February 25, 2007), 3.

[37] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Stand Up for Truth” (BYU devotional speech, September 17, 1996).