"What a Power We Could Have"

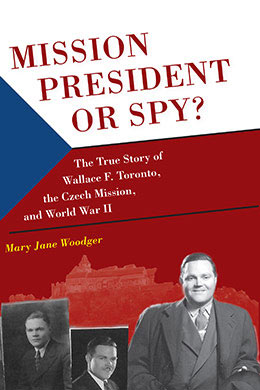

Mary Jane Woodger, "'What a Power We Could Have'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 69–80.

During the mid-1900s, missionaries spent only one week in a missionary training facility. Then they went directly into the mission field to which they had been assigned. It then became “the mission president’s responsibility to train his new missionaries in the language and gospel study.”[1] Wally took this responsibility seriously. He tried to assign elders to the right district, town, or city and then transfer them so they were with the correct companions. He once noted in his journal, “I plunged into the puzzle of trying to most effectively transfer our missionaries. . . . It is a problem and sometimes a headache to make the best matches between the brethren, and to find capable men to take the positions of leadership and responsibility and who know enough Czech to carry on.”[2]

Toronto had been a mission president for less than a month when he became discouraged at the missionaries’ level of conversion. He wondered why his mission wasn’t having the kind of success of the early missionaries of the Church did, like Wilford Woodruff. The missionaries often reported to Wally that their lack of success was accredited to the people because they were “Godless, irreligious and indifferent.” Wally admitted that the attitude of the people was part of the problem; however, he believed that the main problem, instead, was that his missionaries were less spiritual than those early missionaries of the Church. “Some of these boys are so young. Some need such a conversion! I have come to the conclusion that my hardest job is to convert the missionaries and make them feel their responsibilities. And I sometimes wonder if such a thing is possible.”[3]

He decided the missionaries’ biggest disadvantage was that they were “life-timers” instead of converts to the gospel. He informed his missionaries, “We have been born into the church—which we cannot help. We have never had the stimulation at home, perhaps to study out the Gospel and thus gain a burning testimony of its divinity. This may not be our fault. We have been brought up to take things for granted.” He then offered them some encouragement. “It is not too late. It is a sorrowful thing that some missionaries leave the field after two or three years with their spirituality little improved. It is only because they never strove to attain it. And it is the all-important thing in successful missionary work.”[4]

Wally lamented in his journal about his desire to motivate the elders in his care: “If our young men—more of them—were only leaders, who could make opportunities, when they do not seem to exist, or who could push the work with the pace and the enthusiasm which is required! Had we such men the work might grow and take on larger proportions. The greatest problem seems to be with the missionary himself—to help him convert himself to the Gospel, and make the conversion so successful and so complete that he feels his obligation to use every minute in worth-while endeavor.”[5]

Wally’s schedule constantly included time set aside for dealing with the problems of missionaries. Whenever new elders got to Czechoslovakia, he could quickly identify what each missionary’s problems were. In one journal entry, he observed that one missionary was a bookworm and continued to study, never joining in games or entertainment. Another lacked the qualities of leadership. Another typical problem was that the Czech missionaries “had formed a ‘Dear John’ club that grew as time went on,” and it took a toll on the morale of the mission.[6] After dealing with that same issue with so many missionaries, he stated, “This discouragement among missionaries is one of the worst problems I have to deal with.”[7]

One missionary seemed to be “somewhat soured on the work” and felt he had “done little or no good” because he had not converted anybody. He went to the mission president and suggested that he be sent “home because of some throat trouble”, but Wally knew that it was just an excuse. He observed that the missionary was not happy in the field and that he had a difficult time getting along with his companion. He was not what Wally called a “pusher” and did not “know the art of getting along with people.” Wally threw up his arms in defeat. “I hardly know what to do with him to help him change his attitude.”[8] Similarly, another companionship was not getting along either. They got into arguments and exchanged some very unkind remarks toward one another. In frustration, Wally recorded in his journal, “If we as missionaries can’t demonstrate the Christian spirit among ourselves, how can we expect anything of the members.”[9]

One missionary was becoming very discouraged over the language and went to Wally and explained his concern that he didn’t know how to speak Czech very well. The inactivity in the Žižkov Branch, where he was working, was very high, and the elder feared that his lack of ability to speak the language would not help matters in the branch. After Wally talked with him for a long time about the problems, he felt he had been able to encourage him to succeed. They prayed together about the matter. At the end of the interview, Wally felt that the young man was a fine boy with a very willing heart.[10] Toronto also wrote in his journal about yet another such elder. “I had an opportunity to talk to Brother Ward about his work here. He would like to leave for home when two and a half years are up. He is somewhat discouraged with our results, as are many of the brethren, and in view of our results is unable to see the deeper value of missionary activity. However, he said he would leave the decision in my hands and carry on as best he could. This work is difficult and tries the faith of these fine young elders. There is no doubt of that.”[11]

Wally was sometimes less successful than he hoped to be with a few of the young elders. In particular, he felt that one missionary who desired to go home was a “damper” on the work. He was only doing “enough to survive” until he was released. Wally tried a number of ways to inspire the young man, but it was useless. He eventually came to the conclusion that he would have to let the missionary go for the sake of the other missionaries because his bad influence was dampening the strength of the whole mission. Whenever Wally had to send missionaries home, it always broke his heart. However, Wally never gave up on his missionaries. Even after they returned home, Wally stayed in contact with them and would try to straighten them out if they had strayed from the Church.[12]

One very different problem also plagued several missionaries. Wally recorded one instance in his journal:

I happened to see Brother Williams and Brother Merrell with a very attractive young lady. I went over to them, and when they saw me coming they turned color a bit. However they introduced me, and then she told me that they were taking her to a show. The brethren knew they were in a pinch. I told them in English that I would expect a complete explanation in the morning, and left them two very surprised young men. The following morning they came out to the office and I bore down upon them and suggested that such a thing could result in a dishonorable release. They felt pretty uncomfortable about the whole thing. Brother Williams said that he just felt like “busting loose” and that he didn’t know why he had done it, in the face of our strict mission rules about associating with girls. However, the brethren swore that it was the first time it had happened and that it would be the last. And I am sure that it will be. If there were ever two contrite brethren, it was them. Oh, the life of a mission president! One problem piles upon another.[13]

Likewise, when other reports reached him of missionaries seeing girls, he called the elders into the office and told them that if they continued to meet with young women, “it would mean a release from the mission.”[14] One missionary became suspicious when his companion kept going out alone, and he reported it to Wally. When Wally confronted the elder, he defended his activities by saying that a young lady was making advances. Wally informed him that he would have to “overcome ‘her advances’”, and if he did not, Wally would have to “do something drastic.”[15]

Problems involving girls with the missionaries posed a constant frustration. In his journal, Wally recorded incidents concerning his missionaries falling in love and making promises to take Czech girls home but then failing to keep their word. As a result, Wally often had to handle the heartbroken women who were left behind.[16] For instance, when a certain elder neared his release date, he talked to Wally about his feelings toward one of the women of the branch. He informed Wally that he would undoubtedly write her an offer of marriage once he got home. Wally told him to get his feet on the ground once he returned to the states, associate with other girls, and then write to the sister in the branch after six months if he still felt the same about her.[17] Such situations seemed to occur over and over again. Wally convinced another elder who wanted to take a Czechoslovakian sister to America not to have her go.[18] The elder had told the sister before he left Czechoslovakia that he was in love with her and would send for her soon. When six months passed, and the girl heard nothing from the returned missionary, she was heartbroken. Wally had told the elder to be careful, for she “ha[d] a bad case on him.” Wally grieved, “This girl problem is difficult at times.”[19]

In another instance, another elder had become involved with a young Czech woman while on his mission. He promised to send for her, but he never did. Instead, when he returned home he married someone else, but for two years the Czech girl received no letters from him telling her of his marriage. When the returned missionary finally wrote her, he told her “that he was still in love with her and always would be.” Wally wrote, “The whole letter seemed empty and queer—as though he were trying to cover up his shame for not writing her earlier about his marrying another girl, when he had promised to send for her. I advised her to write and tell him that everything was over, as far as she was concerned, and that she did not care to hear from him again.”[20]

When another missionary promised to send for a sister in one of the Czech wards, Wally wrote, “She expected that he would, and has been keenly disappointed. But I told her of his utter undependability, and indicated that he had had other experiences with other girls while on his mission—and that of all our missionaries he was one of our least useful. This is a hard thing to say about a brother, but it is true. He caused many a head-ache.”[21]

Another challenge tested Wally’s unique ability to handle difficult situations. Elder Mel Mabey described an experience he had with one of his companions who struggled with homosexual temptations. The companion never approached Elder Mabey, even though they slept in a double bed. When Mabey discovered that his companion was struggling with same-sex attraction, he went to his mission president. He was distraught, and he sobbed as he talked to Wally. He wondered how he could best handle his companion’s situation. Wally told Elder Mabey to confront his companion and tell him that he knew he was homosexual. At the time, Mabey thought that was the “weirdest advice [Wally] could give him.” He was surprised that Wally did not send his companion out of the country. But Wally understood that this elder only experienced the temptation and that he had not acted on his desires. Wally knew there was no reason to send him home. Elder Mabey took his mission president’s advice and talked with his companion. Mabey respected Wally’s advice. He likewise appreciated the fact that he had decided not to send his companion home because his companion was, indeed, a very good missionary.[22]

In the face of such problems, Wally balanced discipline and encouragement. He believed that every missionary was worthy of whatever help he could give.[23] He tried to get the missionaries to see their possibilities. “What a power we could have in this mission if every brother were qualified to teach and preach the Gospel and had the enthusiasm and the energy, which such a calling demands! If such were the case, our work, I truly believe, would grow leaps and bounds. I am convinced that the type of young missionaries the Church sends out is largely responsible for the few converts we gain for the cause.”[24]

Wally successfully encouraged many missionaries and built them up through his writings in The Star: The Czechoslovakian Mission Newsletter. He spent a considerable amount of time writing the monthly messages and “attempted to put into the article some thoughts which might inspire the young missionary.”[25] At one time, he wrote:

During the year many of you have become effective in the use of the Czech language. Your general tone of cooperation and your enthusiasm has been especially invigorating. You have had many difficulties to overcome, and on the whole, have been very successful in grappling with your problems. You have also been receptive to suggestion from the mission office. You have carried out, with few exceptions, the regulations necessary to missionary work. You have been successful in planning and adapting yourselves to a daily program of activities, the splendid results of which are to be readily seen in your increased knowledge of the Gospel, in your extended powers of perception and in your preparedness and ability to bring honest souls to a knowledge of the Gospel. Yes, Brethren, it is a joy and a privilege to preside over a group of fine, strong, persevering and faithful personalities such as you are. This is the richest experience of my life. You have made it so.[26]

In another newsletter, Wally wrote to his missionaries about being clean:

To come through clean, [a missionary] must not only keep himself morally upright, but that he observes every regulation and code of conduct which the great missionary fraternity, numbering hundreds of young men throughout the world, demand of him, that he deal honestly from great undertakings down to the smallest item scratched on his daily report; that he devote every minute of his time while in the mission field to hard, conscientious, diligent work; that he never lets an opportunity go by to preach and teach this gospel; that every thought for self be sublimated in the glorious light of service to others. This—yes, all this, is “coming through clean.”[27]

Wally told the missionaries that the greatest desire not only of their parents or of their mission president “or even of your church itself—but of the Lord . . . is that each and every one of you can, at the conclusion of your missions, say, ‘Lord, I am grateful for this opportunity. I have done my best. I have come through clean!’”[28]

Wally admonished his missionaries to pray nightly that the hearts of those they had contacted would be touched by the Spirit. He also had them pray for success with their companions and suggested that they go with their companions to a secluded spot and talk to God when in need of help. He advised them to fast and pay fast offerings as well. He told them that such behaviors would demonstrate to Father in Heaven that they were serious, that they were putting “service before self.” He counseled them to be more sober in their work, and then they would be led with the Spirit. He encouraged the missionaries to be out of their apartments by 9:30 in the morning, eager to serve and to touch someone’s heart with their message.[29] Elder Mabey explained that Wally “knew how to relate to missionaries, to get everything out of them,” and he certainly upheld some high expectations of them.[30] Because President Toronto loved the missionaries so much, they returned the sentiment.[31]

Wally was still in his late twenties, barely older than his missionaries. Even with such a small difference in age, he had the ability to consider the missionaries’ youth and not take incidental things too seriously. Missionary Dale Tingey recounted how he had planned to see the Nuremberg trials with some other missionaries.[32] He had wanted to stay in Switzerland for a while longer to ski. As the senior companion, he should have been a better example. Wally called him and asked where the other missionaries were. Tingey informed him that he had sent them ahead, so he did not know where they were. Wally scolded him a bit. When they met at the train station, he asked Elder Tingey again where the other elders were, to which Tingey replied that he had already told him before that he sent them on ahead. Wally was quite upset with the elder. “He said, ‘Now Tingey, I have half a notion to put you on the night plane and send you home.’ So I said to him, ‘If you feel good about that, I would feel good about it because I really didn’t want to come in the first place.’ . . . He just says, ‘I’ll tell you one thing, Tingey. You’re not going home.’”[33]

The missionaries had great respect and love for Wally because he was so much like them. One day, an extremely agitated Elder Abbot stormed into Wally’s office waving a paper and yelled, “Look what these sons of b****** have done to me!” Abbot threw the paper across the desk and informed Wally that they were throwing him out of the country and not renewing his visa. Wally calmly looked at the elder and responded, “Brother Abbot, don’t refer to my brethren as sons of b******. Refer to them as the BBBs.” Abbot questioned, “The BBBs?” Wally answered facetiously, “The black belly bastards.”[34] He clearly knew when to be serious with his missionaries and when to use humor. At a conference in Prague, he told the elders to bring swimming trunks. When they found themselves on the Modow River, Wally joked, “Brethren, we’re all going down seeing a little more of each other in the Modow.”[35]

Wally also encouraged his missionaries not to use notes when giving their talks. In a mission president’s message, he said:

I believe that the effectiveness of delivering a well prepared lecture or speech without a paper, was brought forcibly to our attention in Mnichovo Hradiště. Two of the brethren spoke without a paper . . . and held their audience spellbound. To do this with Czech requires that the talk be carefully prepared and written, and then either memorized or placed sufficiently well in mind that one can deliver it without the aid of a paper. Brethren, if you will do this, you will gain that all-important link of interest between yourself and your audience, namely, that fascinating contact of eye to eye.[36]

Toronto then went on to challenge the elders:

I would like you to give at least one talk a week without reading it before an audience from your paper. Yes, put in plenty of time preparing it and writing it out, but put in that much more time learning it. True, this is the harder way. But it is the more effective way and will pay you big dividends in the long run. If you will earnestly attempt to do this over a period of a few months, I promise you that your Czech will vastly improve and that the attendance at your meetings will greatly increase. Begin this week to do it.[37]

Wally cared a great deal about his missionaries and their success. Likewise, he felt the same way about the Czech members. He visited them in their homes and “built strong friendships.”[38] He planned weeks of spiritual rejuvenation for members, and specifically for the youth. He also promoted “Hike Your Neighborhood” day, during which religious discussions ensued about doctrine or scriptures. These activities strengthened the members’ friendships and assisted in forming a large Church family of brothers and sisters.

Historian Kahlile B. Mehr shared the following results of Wally’s mission: “For two decades, the Czechoslovak Mission was a lone salient of the Church in Slavic Europe, which besides Czechoslovakia included Poland, Bulgaria, and states of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Missionaries served in Czechoslovakia for fourteen years, from 1929 to 1939 and 1946 to 1950. A total of 286 people were baptized (137 before, 10 during, and 139 after World War II).”[39]

Notes

[1] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 5.

[2] Toronto, Journal March 27–April 2, 1938, 211.

[3] Toronto journal, July 26–August 1, 1936, 20.

[4] Wallace F. Toronto, “Our Own Progress Depends on Spirituality and Humility,” Hvězdička, February 1938.

[5] Toronto, journal, August 2–8, 1936, 23.

[6] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 12.

[7] Toronto, journal, February 7–13, 1937, 79.

[8] Toronto, journal, July 26–August 1, 1936, 20.

[9] Toronto, journal, February 7–13, 1937, 79.

[10] Toronto, journal, January 10–23, 1937, 71.

[11] Toronto, journal, July 17–23, 1938, 247.

[12] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 27–28.

[13] Toronto, journal, July 25–31, 1937, 131–132.

[14] Toronto, journal, August 16–22, 1936, 27.

[15] Toronto, journal, August 9–15, 1936, 24.

[16] Toronto, journal, July 10–16, 1938, 244.

[17] Toronto, journal, February 28–March 6, 1937, 83.

[18] Toronto, journal, August 1–7, 1937, 133.

[19] Toronto, journal, January 1–8, 1938, 182.

[20] Toronto, journal, August 6–12, 1939, 394.

[21] Toronto, journal, August 7–13, 1938, 254.

[22] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 9–10.

[23] Toronto, journal, May 2–8, 1937, 102.

[24] Toronto, journal, July 26–August 1, 1936, 20.

[25] Toronto, journal, August 2–8, 1936, 22.

[26] Toronto, “Mission President’s Message,” Hvězdička, January 1938.

[27] Toronto, “Come Through Clean,” Hvězdička, June 1938.

[28] Toronto, “Come Through Clean,” Hvězdička, June 1938.

[29] Toronto, “Some Ways of Gaining Spirituality,” Hvězdička, February 1938.

[30] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 10.

[31] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 24.

[32] The Nuremberg Trials were held after World War II in Nuremberg, Germany to prosecute political, military, and other leaders of the Axis forces (including Germany, Italy, and Japan).

[33] Dale Tingey, by interview Kalli Searle, Provo, UT, transcription in author’s possession, 1.

[34] Bob and David Toronto, interview by August 20, 2013, 24.

[35] Don Whipperman, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, October 9, 2013, phone conversation, transcription in author’s possession, 3.

[36] Toronto, “Speaking Without Papers,” Hvězdička, June 1937.

[37] Toronto, “Mission President’s Message,” Hvězdička, June 1937.

[38] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 6.

[39] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 43.