"The Toronto Mission"

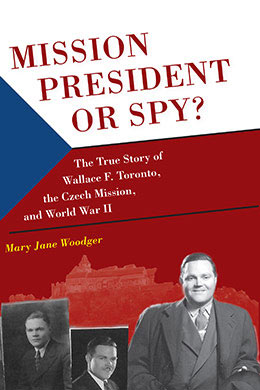

Mary Jane Woodger, "'The Toronto Mission'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 217–224.

In August of 1967, Wally had a kidney stone operation. A few months later, the doctors discovered he had cancer. Everyone felt that a healing miracle was in store for him because of “who he was and what he was.”[1] He had known President McKay and all the other General Authorities. He had been on the Mutual Improvement Association and Sunday School general boards for years. “He knew everybody.”[2] But even though “he had all these high-powered friends” on his side, “he died anyway.”[3] Wally received no miracle. Martha gave her husband shots for pain and tried her best to keep him comfortable as he suffered the last of his mortal days.[4]

After enduring radiation, Wally admitted, “That’s it. This is just not working.” His health began to decline quickly once he terminated treatment. The family had a hospital bed placed in the front room. Wally stayed on that bed until the last several days of his life.[5] Suffering greatly, he asked President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency to administer a blessing.[6] In the blessing, he told Wally that he was appointed to death. At just sixty years old, he passed away on January 10, 1968, in a Salt Lake City hospital.[7] He died “of the disease against which he had crusaded for 16 years as director of the Utah Division of the American Cancer Society.”[8] President Brown graciously spoke at his funeral.[9]

The Czech Mission was left without their mission president. Wally had served as president since 1936. For thirty-two years, he held that position, most of that time directing the mission from Salt Lake City. “When the presidency of Wallace Toronto ended with his death in 1968, the Church’s tenuous contacts with the outside world continued.”[10] President Brown asked Martha to carry on as mission president in Wally’s place until they could figure out what to do with the mission.[11] President McKay, too, asked her to “run the mission until [they] could get somebody in there.”[12] Almost as soon as she was called, she began writing to the Saints in Czechoslovakia, just as her beloved husband had done. She guessed that she was the only female who had ever served as a mission president.[13]

The appointment did not last long, however. Once the Czechoslovak Mission was joined with the Austrian Mission a few months later, she was released.[14] Church officials went to collect the materials from the mission and place them all in the Church archives. Everything Martha had in relation to the mission was taken after her release,[15] “her letters, their letters, pictures, photos, albums, everything.”

Even before his death, Wally prepared the Saints for what they were going to go through. People even regarded him as a fairly visionary man. He seemed to know “that this was all coming, and he did everything he could to fortify it. He, in a way, prophesied that it would get worse.” He knew that the missionaries would eventually be expelled from the country and have to leave. “He tried to prepare the people and . . . instill in them that the gospel [was] the most important thing. If they would stay with the Lord and the gospel, then they could survive anything. . . . He had a vision of what was coming, . . . and that there would be a day when they would be free again, and the Church could prosper there.” He said, “They have to look forward to that vision. We’re going to have dark days now, but there’s a vision of what will happen when the Communists are gone.”[16]

Missionary Dale Tingey talked about how “[Wally] was able to build up their confidence.” It was extremely important to Wally that he organize everything in such a way that “they could carry on alone without him. . . . His greatest contribution was that he was an example of the Church to the people, and example of what we should do with our families, an example of how they should love one another and support one another.” Wally inspired the Saints of Czechoslovakia as nobody had before. “He had the big picture of what was coming down the track and [knew] to prepare for disaster. . . . Beyond that there would be hope and faith, and the Lord would be with them if they would just stay with the Lord.”[17] Tingey described Wally with the utmost respect:

I remember him as a very courageous, dedicated person. I was with him when he talked to the Communists. He almost scared me. He’d just say these things [like] “Know the truth, and the truth will make you free. You’re trying to take this away from people.” . . . He was very brave. In his talks in Church, even when there were Communists there, . . . he didn’t kowtow to them at all. He’d just tell them what was right. . . . The youth said to us, “You believe in a Christ that’s been dead for 2,000 years . . . ?” He’d say, “That’s right, and who do you believe in?” And they would say, “We believe in Stalin. He is . . . the rising star of the East. . . . Someday you’ll see that rising star, that red star, flying over the capital of the United States.[18]

Even with all the preparations Wally made, the Czech Saints were distraught at his passing. Only a few months later, Czechoslovakia experienced the “Prague Spring” of 1968:

The Czechoslovakia of old surfaced when Alexander Dubček became leader of the Czechoslovak Communist Party and instituted a series of liberal reforms, including more freedom of the press and increased contact with non-Communist countries. Encouraged by these actions, Ceněk Vrba, Jiří Šnederfler, and Miroslav Děkanovský—three stalwarts of the Church—petitioned for religious recognition. However, hopes were dashed when Warsaw pact troops and tanks, under Soviet orders, crushed the progressive regime and quelled any hope of reviving the Church. Despairing at the lack of religious liberty, the Vrba family from Brno and the Kučera and Janoušek families from Prague escaped with what few belongings they could carry, not knowing what to expect in the non-Communist world, but hopeful that their situation could be no worse. That same year (1968) in far-off Salt Lake City, Wallace Toronto died of cancer.[19]

Along with everything else, Wally’s death was a bitter blow for the Czech Saints. Jiří Šnedefler wrote a letter to President McKay expressing the despair that they felt:

Prague, July 10, 1968.

Dear President McKay,

I hesitate to write this letter, but we are sincerely concerned about the future of our Mission in Czechoslovakia. Since the untimely death of our dear [President] Toronto, we do not have any contact to receive direction and encouragement from the First Presidency and Church leaders.

Many churches are receiving permission to conduct meetings and teach [others] their various doctrines, and we would like you to counsel us in regards to making an application to the government for recognition for our church or for permission to meet together.

The present circumstances are much better than years ago. We have more freedom, we receive The Improvement Era, we surely will be able to work in genealogy, and we could find people who are interested in our Church.

We realize you are so busy you personally cannot be concerned about us, but would it be possible to designate someone who understands us, who would correspond with us, who could help us enjoy the blessings we so much want and need.

We think of you and pray for you and remain with best wishes for you and all the Church.

Sincerely,

[Jiří Šnedefler][20]

Wally had understood and corresponded with them, helping them to enjoy all the blessings that they had received. But he was gone. Wally had warned them that when the Czech people received their freedom, there would be fewer conversions than in the days when they were under Communist rule. He believed that they would lose converts even faster. That was his exact reason for encouraging the Saints to be more careful and diligent with whom they taught and how they taught them.[21] Nevertheless, the Saints were yearning for religious freedom in their country and inspired guidance from the Church.

Czech historian Johann Wondra expressed, “The Czech government didn’t want to have a situation like in Poland. In Poland, there was a strong Catholic church, but this was not only a Church; it was a political position. . . . Therefore, the Czech government . . . [was] very aggressive against every religious [intention] and [activity].” Every second Sunday, the people of Czechoslovakia fasted and prayed that the Church would somehow be officially recognized in Czechoslovakia. “It was the Toronto mission. . . . [Wally] really knew how the people in Czechoslovakia felt” about the situation.[22]

From the time Wally was evacuated, Jiří Šnedefler served as the district president in Prague and did so for many years. Otakar Vojkůvka served as the priesthood leader in Brno. Both were authorized to perform all of the ordinances—sacrament services, baptisms, confirmations. However, as Johann Wondra (who was the regional representative at the time) reported, Jiří Šnedefler had to be careful not to reveal who had joined the Church. When someone was baptized, he sent Elder Wondra a postcard with a beautiful lake on the front. To signify how many people were baptized, he wrote something to this effect: “Last Sunday we were swimming with eight friends.”[23]

The local leaders were careful not to reveal the names of those who had been ordained to the priesthood either. In order to get the names into Church records, Elder Wondra traveled to Austria. However, because he could not risk taking written information across the border, he memorized it all before he began his journey. Once he was safely in Austria, he wrote down names of brethren who had been ordained. If such information fell into the wrong hands, the government would incriminate the Czech Saints, for at the time Czechoslovakia was the most terrible of the Communist countries.[24] The objective of the leaders was to avoid drawing attention or suspicion to themselves, and they were blessed with success.

“The great loss was the children,” said the Morrells.[25] Marion Toronto, who later served a mission in Czechoslovakia, expressed, “The Communist regime . . . didn’t allow religion—period. It was a totally atheistic country and so that made it very difficult for the children [of Latter-day Saints].” In fact, if the parents “did speak about God or religion in any way, their families were in danger. So if their children stayed faithful, they had to do it in terrible secrecy. And a lot of their children just didn’t bother.”[26] They resented the fact that they were kept out of universities and that they “didn’t have much chance” simply because their parents believed the Church was true. Jiří Šnedefler had one son who had gone to Church when he was single. However, he married a woman who was extremely opposed to it. He drew away and “broke the liaison between the father and the son.”[27] Marion realized, “It’s a hard, hard mission. . . . It’s always been a hard, hard mission.”[28]

Despite all the difficulties and setbacks that constantly faced them, the Vojkůvka and Šnedefler families held the mission together after Wally died. After the “Prague Spring,” Brother Šnedefler quietly began applying for recognition of the Church.[29] Gad Vojkůvka compared Wally and his mission to Moses and ancient Israel. The Israelites wandered in the desert for forty years before they had the privilege of entering the promised land. But Moses could not join them there. Similarly, Wally died before the Church gained legal status again in the Czech Republic. The Saints suffered many years in secret worship. But even though Wally could not visit them, he continually wrote to them and prayed for them.[30]

Wallace Felt Toronto was, in a sense, the Moses of Czechoslovakia. He gave his heart to the Czech people and to the Czech Mission. He was a powerful but humble leader. He invested time in developing love for the one. He learned about the culture and customs of Czechoslovakia. Consequently, he was able to gain the trust of the people and lead them through the most difficult times of despair and hardship. Wally did everything he was asked to do, despite great sorrow. Although he never had the privilege of witnessing the joy of the Czech members when the Church was legalized again, he did everything in his power to push the Church in that direction. The response of the Czech Saints at the time of his death encompassed the intensity of love and respect that the Czechoslovakian members had for their compassionate leader. Wallace Toronto’s thirty-year contribution to the Czechoslovak Mission was incredible, to say the least. His son David understood that if someone asked his dad what he had accomplished, Wally would simply reply, “I was just doing what I was asked to do.” Bob added, “And, in fact, that’s exactly what he did.”[31]

Notes

[1] David Toronto interview, Daniel Toronto, 2010, 5.

[2] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 17.

[3] David Toronto, interview by Daniel Toronto, 2010, 5.

[4] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 109.

[5] David Toronto interview, 2010, 6.

[6] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 2013, 17.

[7] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 109.

[8] “W. F. Toronto Dies In S.L.,” Deseret News, January 10, 1968.

[9] Funeral Services for Wallace Felt Toronto, January 13, 1968, copy in author’s possession.

[10] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 51.

[11] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 110.

[12] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 29.

[13] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 110.

[14] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 110.

[15] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 29.

[16] Dale Tingey interview, 4.

[17] Dale Tingey interview, 3.

[18] Dale Tingey interview, 4.

[19] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 92–93.

[20] Jiří Šnedefler to President David O. McKay, July 10, 1968, as found in Jiri Šnederfler papers, Europe Church History Center, Bad Homburg, Germany, copy in author’s possession.

[21] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 32.

[22] Johann Wondra interview, May 30, 2013, 2.

[23] Johann Wondra interview, May 30, 2013, 18.

[24] Johann Wondra interview, May 30, 2013, 18.

[25] Ed and Norma Morrell interview, May 8, 2013, 17–18.

[26] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[27] Ed and Norma Morrell interview, May 8, 2013, 17–18.

[28] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[29] Ed and Norma Morrell interview, May 8, 2013, 17–18.

[30] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 8.

[31] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 17.