"Satan's Workers"

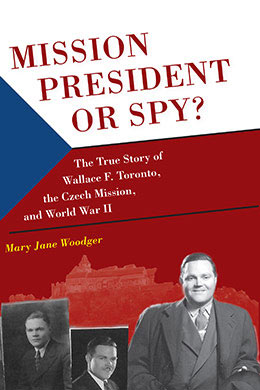

Mary Jane Woodger, "'Satan's Workers'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 167–190.

As soon as Martha returned to Prague, she adjusted quickly back into her role as mission mother. Her duties, along with taking care of her own family, included other Church callings such as overseeing the Relief Society in each of the larger branches. She tried to execute several programs as outlined in the Relief Society Magazine and supervised the translation of Relief Society lesson materials into Czech. In addition to those responsibilities, she managed the mission home. Because of a housing shortage, many missionaries ended up staying at the mission home for several months instead of weeks. The Mutual Improvement Association also held their meetings at the mission home. Many of the Church’s new converts were young adults. Kahlile Mehr explained that the Church in Czechoslovakia was constantly getting younger: “The average age dropped from thirty-six in the prewar period to twenty-nine after the war.”[1]

The Latter-day Saint young adults tried to seek converts in various ways, including through sports, especially volleyball and basketball.[2] LDS young adults revitalized the tradition that Wally started years earlier. As a result, member friendships strengthened, and the Church increased as a family of brothers and sisters. The focus of the activities was first on friendship, brotherhood, and sisterhood. “Then the way to the Church was open [in] a matter of time.”[3]

Missionary Dale Tingey talked about how well Wally worked with the young Czech Church. “He [was] organized. It was more than just church. He wanted the people to work together.” Wally wanted his missionaries to help the members be better Saints, to be better in their families. He wanted to protect them against the coming onslaught. He told them that they would surely “be in very difficult circumstances.” As a result, “all of his programs were designed to try and strengthen them in small groups so they could carry on after [the missionaries] left.”[4]

Wally visited members in their homes to build friendships. He attended every baptism when possible. “Everyone knew him well and viewed him as their father.”[5] Bob Toronto remembered going with his father to baptisms, which often took place in a spa or a pool.[6] Wally organized public discussions where he again presented movies and spoke about “Utah—majestic land of America,” followed by a discussion on religion and the people.[7] He shared his messages wherever he could: at the YMCA, the British-American club, Scouts meetings, and at other organizations. He also utilized the media. He started the Church magazine Nový Hlas (New Voice), a monthly religious and cultural magazine for both members and nonmembers, which made Church doctrine available to people who were not very interested but who still had questions.[8]

Wally wanted his missionaries to listen to the Spirit when it came to teaching investigators. He did not want the missionaries to go too far too soon and leave their investigators confused and overwhelmed. “When you teach the gospel, teach them so they want to know more not because they’re saturated.” Using an object lesson to explain the concept, he had someone bake two little cakes and decorate them beautifully. He asked the elders, “Does this look good to you?” The missionaries, who were all famished as usual, responded, “Yes! Yes!” He then asked, “Who would like to be the first one to have a piece?” When the missionaries all raised their hands, he took the cake and shoved it in one of their faces.[9] The lesson proved his point most effectively. From then on, they did their best not to bombard investigators with too much information.

On every July 24, Wally continued to have members and their families commemorate both the Mormon pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley and the dedication of Czechoslovakia for preaching the gospel. He used the event as an opportunity to invite nonmembers and their families to hear interesting and positive things about the Church for the first time.[10] He also planned a pageant around that day each year “to demonstrate by historical presentation how the Czechoslovak lands were prepared ‘line upon line, and precept upon precept’ for the advent of Christianity and the later restoration of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, with the subtheme of ‘Peace and prosperity are complimentary with righteous living.’”[11]

Elder Ezra Taft Benson of the Quorum of the Twelve had been sent to Europe as the administrator of Church humanitarian aid. He arrived in Czechoslovakia in 1948 and worked closely with Wally. Wally arranged for him to speak in Prague and as well as in Brno, which at the time was the capital of Moravia. Almost 1,500 people gathered in a large auditorium to hear Elder Benson. There were even Communists in attendance who were “very interested in learning more about the Church. They exhibited more interest than a lot of the other people.”[12] Wally made the arrangements for the meeting and gave his own comments, speaking excellent Czech and German.[13] “A steady stream of missionaries began to swell the mission forces. In August 1947, six missionaries joined the four that had come with the Toronto family in June 1947. In October 1948, the proselytizing force totaled thirty-nine, the largest group of U.S. citizens in Czechoslovakia except for the U.S. embassy staff. . . . Attendance at Church meetings reached unprecedented levels. Tithes and offerings increased, . . . [and] Toronto’s lectures typically drew crowds from seventy to nine hundred.” At one particular lecture, “two hundred people had to be turned away due to lack of space. Opposition engendered a greater commitment among members and increased interest among those not yet of the faith.”[14]

A total of thirty-six missionaries served in the Czechoslovakian Branch after the war. Years later, missionary Ed Morrell went into the archives of Czechoslovakia and looked at the government records to find what was written about the Mormons at the time. There he found names, addresses, photographs, and information about Wally’s role. Additionally, missionaries serving in Brno from 1946 to December 1947 were listed with their backgrounds, especially if they had been in the U.S. military. “Another two sheets (dated March 16) counted twenty-eight Mormon missionaries, former American army officers and non-coms” (noncommunists). Two descriptions of missionaries humorously listed, “he washes and dries his own laundry.” A very large file, dated February 4, 1948, discussed “meetings in Mladá Boleslav and five ‘preachers of Jehovah’ led by Toronto,” driving a Ford vehicle with the Utah license plate H 9260. They also documented a particular meeting that Wally had led in Olomouc in March 1948, which 250 individuals attended. Six elders were listed in Brno and one in Olomouc. Nine of fourteen were thought to be in Prague, and the other five in Mladá Boleslav. An account dated April 1948 concluded that the missionaries were “masked agents of the American intelligence service.” Then there was something written about how “this Church should be forbidden in the CSR, or at least the number of missionaries appropriately reduced.”[15]

Free Czechoslovakia survived less than three years after World War II. “Soviet leaders pressured the Czechoslovak government to appoint high-ranking officials of Communist persuasion.”[16] Noncommunist leaders in the government were fighting hard against those of the Communist Party. Among the lovers of democracy were Edvard Beneš, the president of Czechoslovakia elected in 1935, and Prokop Drtina, the Minister of Justice. “Under Interior Minister Václav Nosek, the security forces, the National Security Corps (SNB) and State Security (StB), became weapons that the Communists could use against their political enemies.” Drtina managed to expose the conspiracy before any further action could be taken, but damage had already been done. “The policies of Nosek and the police led to the arrest of some 400 people.”[17]

Despite their high ranks in the government, they were unable to hinder the unstoppable progress of the Communists. In mid-February, Drtina reported an incident to the cabinet in which “the remaining eight noncommunist district police chiefs [were to be] transferred out of Prague.” Nosek had supported the transfers. The other noncommunist members of the Cabinet ordered Nosek to “reverse his position and prevent the transfers.” Furthermore, if Nosek refused to oblige, “the noncommunist ministers, with the hoped-for participation of the Social Democrats, would submit their resignations and bring down the government.” Their intention was for President Beneš to either “appoint a short-term government and schedule new elections or refuse to accept the resignations and force the Communists either to negotiate with the other coalition parties or accept responsibility for the government’s dissolution.”[18]

Missionaries who reopened the Czechoslovak Mission, 1947. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Missionaries who reopened the Czechoslovak Mission, 1947. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The support of the Social Democrats “failed to materialize.” Their plan had entirely backfired. Instead of the Communist Party bowing in submission, Beneš and Drtina along with their allies were forced out of the government. The prime minister and leader of the Communist Party, Klement Gottwald, gladly advised Beneš to accept the resignations. Beneš tried to find a way out of the mess, but he was defenseless. “Exhausted, in poor health, and believing he was without any viable options, Beneš conceded.” The formidable events of the month became known as the Communist coup d’état of February 1948.[19]

Some of the events that transpired in the aftermath shocked everyone. After Drtina was stripped of his position as Minister of Justice, he “allegedly chose to end his own life by throwing himself from a third-story window on February 26. In the early morning hours of March 10, Jan Masaryk became another victim . . . as his body was discovered dressed in pajamas below the window of his apartment at Čzernín Palace, the home of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Communists quickly announced to the nation that Masaryk’s death had come at his own hand, but friends and colleagues responded by accusing the Communists of covering up a murder.” Masaryk’s death remained a source of controversy for many years. He was, after all, the well-liked son of the beloved “George Washington of Czechoslovakia,” Tomás Masaryk. An investigation conducted in the early 1990s pointed to suicide, but “forensic research by the police in Prague in 2004 [supported] the accusation of murder.” Edvard Beneš resigned from his office of president on June 7, 1948. “On September 3, he died a defeated man at his villa in Sezimovo Ústí.”[20]

As Martha put it, “We found ourselves shackled to the Communist regime. The Iron Curtain had fallen, and this fact changed our lives and our religious work considerably.”[21] After the Communist coup, “the government began controlling all businesses, industries, churches, and schools. Mormon missionaries came under secret police surveillance. The police ordered publication of the mission magazine, Nový Hlas (New Voice), to cease, ending its influence [on] over three thousand readers, mostly members of other faiths.”[22] The Communists seemed determined to make things as difficult as possible for the Torontos in the hopes that they would simply go away. Their efforts, however, made the Torontos only more determined to succeed under such difficult odds. Police officers threatened the members for going to Church meetings.[23]

The Communist coup of February 1948 changed everything. Many elders watched in horror as they witnessed the police shoot people right in the center of town in Brno. Some people who opposed the regime just disappeared. But President Toronto always did what he could to help people understand that the gospel was the greatest strength that they could possibly have to fight their fear. To ensure their safety, the elders always worked through Wally. “If we had anything that we wanted to do, we would have to get permission from Prague and President Toronto . . . to pass out certain tracts . . . to people informing them of the Church. He, of course, would require that we say it in his way so that we didn’t offend anyone.”[24]

Wally persistently reminded the missionaries to “be careful.” In an effort to heed his warning, they started getting creative in their strategies while tracting apartment buildings. They started at the top of the buildings instead of at the bottom. If the Czech people did not like them, they would call the police. So, if the elders started at the top, “[they] could get out of the building, but if [they] started at the bottom and worked up, the police could catch [them].”[25]

The mission was once again approaching peril. It was a well-known fact that the Mormon missionaries were only interested in spreading the beliefs of the Church, for they had been proselytizing for many years without unrest.[26] Nevertheless, the new government became increasingly suspicious of the LDS missionaries and believed they were spies for the U.S. government. When the missionaries told them about the Book of Mormon, it “seemed to scratch a scab on their nose.” Missionaries had to be very careful when teaching the Book of Mormon in a way that would not be offensive. There were always Communists present in their meetings, especially those held in Brno and Prosteel.[27]

Missionary work was “being hampered more and more by the new regime,” which had ironically promised “greater freedom, equality, job opportunities, more food, greater luxuries, and so on.” All of it turned out to be what Martha called a “great joke. Job opportunities turned out to be a form of forced labor.”[28] Missionaries were repeatedly “accused falsely of espionage and were threatened with expulsion for being a menace to the peace.” Wally encountered “new and terrible problems” as time went on. The secret police began following many Latter-day Saints, including the Toronto children. Marion remembered being followed home from school on a few occasions, which naturally made her parents very nervous. “It was necessary to pass a Jewish cemetery on my way from the tram to the mission home. The street had huge trees on one side and the cemetery wall on the other. It was frightening to see grown men stepping behind a tree to avoid being seen,” she remembered.[29] Martha also found it very difficult to endure the paranoia of being watched constantly. It took her a while to lose the feeling of uneasiness. “If you live with it long enough, you do get used to it,” she wrote.[30]

Unidentified missionary with Wallace Toronto in Brno, 1947. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Unidentified missionary with Wallace Toronto in Brno, 1947. Courtesy of Church History Library.

It appeared as if the government was waiting for someone to slip or make a mistake that would incriminate the Church. “God and religion were suddenly frowned upon. People mysteriously disappeared from the streets, never to be heard from again. Everyone walked in fear. Even mothers and sons could not trust each other.”[31] Because Communism “was an atheist organization at its core it focused on repression of all forms of religion,” although it eventually accepted eighteen churches and religious organizations.[32] However, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was not one of them.

When the Communists came into power, Martha explained, “Suddenly we found ourselves restricted in missionary activities. We all had to report to the secret police office and register there as aliens, giving reasons for our being in the country. We had to abide by rules and regulations that seemed very stupid to us.” They even had to submit any speech that they had written to the authorities so it could be censored. Then, if they were unsatisfied, they had to rewrite the speech. Eventually, after the authorities were satisfied, they could present the speech. Nevertheless, agents always attended the meetings “to see if everything went along as it should. We got used to seeing these strangers in our midst, and we welcomed them along with all our members and friends,” Martha recalled.[33]

Just as the Church faced much adversity because of the antireligious government, other denominations suffered similar repercussions. The Communists felt animosity toward the Mormons and the Catholic Church. In fact, the government probably saw the Catholics as an even greater threat. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had the advantage of being “American.” And as such, they were protected to a degree. The Catholic leaders, on the other hand, were involved in politics. “Efforts to silence the Catholic Church in Czechoslovakia and to sever diplomatic connections with the Vatican led to the imprisonment of priests and nuns, the elimination of religious orders, the closing of monasteries and convents, the subordination of clergy to state authority, and the institution of legal proceedings against bishops and Church leaders.”[34]

Under Communist control, “everyone was afraid to even speak to others.” Wally made it a priority to visit the missionaries personally and…keep track of them to make sure that nothing bad had happened to them. While he was a little worried, he was also “very brave and very outspoken” against the Communists. Wally once said the citizens were “kind of bootlickers . . . because they’ve been always under someone’s rule. They just got out from under the German rule, and now they’re in the Communist rule. Before that they were under the Prussian rule.” Nevertheless, “[Wally] dearly loved the people and wanted to help them in every way possible.”[35]

The Communists abused and beat the people, but they were careful not to hurt the Americans, of course, because they did not want to raise any suspicion. Wally spoke bravely against the government to Church members. “They’re all Satan’s workers. You just have to hold on and keep the faith. They’re wicked; they’re cruel.”[36] He refused to back down. In July 1948, he organized a meeting for the president of the European missions, Elder Alma Sonne. Branch President Vojkůvka in Brno threw out airplane leaflets with an invitation to go to the meeting. Elder Sonne spoke to the thirty-nine missionaries on that occasion. “[It] was the largest meeting in European Church history, with 1,800 people attending.”[37]

In February of 1949, the mission held another conference. One Czech member expressed the heartache of many as he mentioned that the members sometimes felt like they had no reason to smile. Wally replied:

We members of our Church of Jesus Christ belong to the Kingdom of God. The Church of Jesus Christ isn’t an American church, nor an English church, nor a Czech church; it is for all people. The plan of life set forth in this gospel includes not just this short temporal lifetime; it protrudes into the eternity. We, as members of the Church, have a passport to that eternal afterlife. No matter where we live now while on the earth—in America or Czechoslovakia or Russia—it will last only a short while. . . . If for some reason I wasn’t permitted to go back to America I could be happy with the blessings here. I could smile.[38]

Ironically, during that tense period, the number of baptisms rose from twenty-eight in 1948, to seventy in 1949, and then to thirty-seven in the first three months of 1950. Among the new converts, one was of most importance, a seventeen-year-old named Jiří Šnederfler, who would later become a major Church leader in Czechoslovakia.[39]

Two-thirds of the converts in 1949 were young people below the age of thirty. Mehr explained why the gospel resonated more with the younger generation:

Youth, stirred from the long-accepted traditions [and] finding little in Communist doctrine to sustain belief, may have found meaning in the Church’s message. Only five converts belonged to the thirty–forty age group and ten in the forty–fifty age group. Middle-aged people, stable in their traditional belief, established in their professions, and worried about supporting families, may have been less disposed to take chances by adopting a new religion. Twelve converts fell into the fifty–seventy age group. One would assume this group might be beyond the age of questioning their beliefs, so the reason for their conversion is unclear. However, more than half of these were single adults, suggesting that the Church provided comfort in their partners’ absence.[40]

In the same year, Wally used one missionary tool that particularly attracted young people. Through his efforts, the government permitted the British Mission’s basketball team, national champions in England, to tour Czechoslovakia in February and March. “In four weeks, the team played . . . games in seventeen cities. . . . The missionaries in Czechoslovakia passed out tracts during half-time, gave short talks in connection with the game, and held special meetings to explain the players’ religion. The visit generated more than a hundred articles in the press.”[41] The New York Times published an article on March 1, 1949, reporting the games’ success. “Basketball prowess and preaching skill have been successfully combined by a team of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) who are returning to missionary duties in England after a three weeks’ tour of Czechoslovakia. The team was pitted against Czechoslovak players. . . . The Mormons reported they had won sixteen of seventeen games, and said they had scored ‘just about as well’ in their preaching sessions.”[42]

While 1949 was a year filled with blessings, it did yield some difficult and unfortunate setbacks. All churches had to request official permission to operate from the Department of State. The government did not grant permission to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, nor to the Methodists, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Protestants, or the other smaller churches. Of those, only the Seventh-day Adventists were eventually given permission to operate fairly soon thereafter because they were able to produce 23,000 signatures of local miners. The members of the sect were easy to find due to the religion’s refusal to serve in armed forces, and had opted to work in coal mines instead to increase the industry.[43]

Mehr traced what happened in 1949: “The Communist government soon ceased to grant or renew resident permits for the missionaries, making their presence in the country illegal. In May 1949, officials expelled three missionaries, claiming they were a danger to the nation’s safety and security. By October 1949, the number of missionaries had been reduced to half that of the previous October, leaving only about twenty. Local authorities ordered expulsions. . . . Toronto protested these orders but had no basis on which to reverse them. Though disappointed, the missionaries realized the futility of refusing to leave.”[44]

Martha recorded the events of the second exodus of the Mormons from Czechoslovakia. “By twos and fours our most valuable missionaries and their younger companions were expelled from the country. Younger elders finished their missions in England or the United States where they wouldn’t have to learn another language. The older ones went home with an honorable release. [After] a year had gone by, our missionary force was down to less than half. This process continued until the expulsions were coming quite often, and instead of giving a time limit of two weeks, it gradually got down to three days, and finally 24 hours.”[45]

Elder Mel Mabey encountered many trying obstacles near the forced end of his mission. On several occasions, some members who worked at the American Embassy invited him and his companion to dinner. Mabey and his companion tried to invite them to go to Church, but they feared the consequences of being questioned by the authorities, which would surely follow if they chose to attend. In January 1950, Wally asked Elder Mabey if he would stay behind with his companion as long as they could, but Mabey was immediately expelled as a spy. His mission was then over.[46] Wally stated, “Then finally . . . they expelled me as the last Mormon missionary, and upon being, as they charged me with, a spy against the Communist government.”[47]

Members of the Church suffered greatly throughout the period of Communist power. Gad Vojkůvka’s father was taken into police custody and his factory, and all his property, confiscated. He was sent to Tabor, a camp of forced labor where the prisoners built a metal works factory. “The judge stated, ‘Mr. Vojkůvka, you have to understand. We know you are innocent, but there is nothing we can do!’” He was always an optimist. Instead of letting negative feelings toward the government get the best of him, he simply compared politics to the weather. He was incarcerated when he was ill, so he was re-assigned to an office. There, he noticed that the officials had a folder of a particular color for every individual in the camp. True criminals had green folders; “political prisoners had red folders; priests, bishops, and religious workers had white folders.” His folder was white, so he knew then why he had been imprisoned: he was a religious worker. By the time he was released, which was soon after Wally’s departure, the Church became illegal. While he was still incarcerated, he infused his fellow prisoners with his positive attitude. As a result, nobody committed suicide while Vojkůvka was there, though suicide was sadly very common. But tragically, three people he knew took their own lives after he left the camp.[48]

Like Brother Vojkůvka, every Latter-day Saint was identified by the government and was, therefore, constantly watched by the secret police. They had to be very careful to meet only on Sundays. Even then, they had to hold their meetings in private to avoid alarming the officers. Many members had to stop going every Sunday because someone would follow them on their way to Church.[49] And worse, in only a few short months, the missionaries went from being watched and followed to being arrested. For instance, Elders Stanley Abbott and Alden Johnson disappeared in a remote area near Olomouc while attempting to visit a member. They were charged with entering a restricted border zone and accused of spying. For eleven days, nobody heard from them.[50]

When Church members phoned Wally to inform him of what had happened, he immediately drove out to the branch, which was very close to the Polish border. He found the elders’ apartment sealed up around the doors and windows with some official tape that the secret police used. He chose not to enter, knowing it was a felony to remove the tape and break the seal. The only thing he could learn about the situation was that his missionaries were being held in a Communist prison somewhere. By devious means still unknown, he eventually learned where they were being held. Finding that he could do nothing in the countryseat, Olomouc, he returned to Prague to alert the American Embassy of their arrests. One Church member in particular, who was a lawyer, worked with him to secure the release of the elders. He told Wally, “I know these people and how they function. They would be very happy if you made an international incident out of this. That is what they want. My advice to you is to let this thing lie. If you leave it alone they will release them much sooner. If you bring the U.S. Embassy into it, they will demand ransom or some other form of blackmail.” Taking the lawyer’s advice, Wally did nothing.[51]

With the Abbott and Johnson case pending, authorities promulgated a new law that required all clergy to be native Czechs. They informed the U.S. State Department that the two prisoners would be released only if the other Mormon missionaries were evacuated. Seeing no alternative, Wally told the remaining missionaries to start packing.

Abbott and Johnson . . . languished in prison for twenty-seven days without a change of clothing or a bath. They were interrogated, not brutally but severely, during the first three days. Thereafter, they suffered long hours of loneliness and uncertainty, isolated from the outside world, each other, and the mission. They subsisted on a diet of Postum and black bread in the morning, and soup with a floating meatball in the evening. Eleven missionaries had already departed when word came that the imprisoned missionaries would be released if Toronto could get them passage within two hours. The president raced to the airport and purchased tickets. Plainclothes guards escorted the prisoners by train from Olomouc to the Prague airport, where Toronto gave them their tickets and they boarded a flight to Switzerland. Sister Toronto arrived in time to watch the meeting from a distance and wave good-bye.[52]

Wally was never allowed to see the incarcerated missionaries. The biggest problem for him thereafter was trying to keep the missionaries in the country. “Eventually the accusations of espionage became intolerable.” One by one, the missionaries received notices of expulsion—orders to leave the country within a certain period of time. Wally spent most of his time in police stations asking them to extend the time.[53]

Eventually, as the mission president, Wally advised all the elders working in the branches to close their activities and gather in Prague. Apart from two elders who were working in the office, Wally sent the remaining eleven either to other assignments in the United States or home. As a result, the mission staff consisted only of the president, his family, and two missionaries. The secret police then focused on getting rid of them. Wally began making preparations for his family to leave. “It isn’t easy, even for Americans, to leave an Iron Curtain country. There were so many details—visas accompanied by photos, permission for money, written permission for luggage, even after thorough inspection by custom officials. Visas were also required to travel over all the occupied zones.”[54]

On February 28, 1950, the police arrived at the mission home.[55] Martha grew very suspicious when she noticed a black car and a police escort standing in front of the gate. Two strangers approached the mission home door and asked for Mr. Toronto when Martha answered it. The police also told her that she and her family, and the two missionaries, had forty-eight hours to leave. Packing everything for a single person in that amount of time was hard enough. She had to pack up everything for six children too. Anxiety gripped her as she made her way to her room, expecting the worst of the situation. Wally went to her and explained that he had to leave with them.[56] “I’m sure they want to question me about the two elders who were flown out to Switzerland. . . . I have everything here for you. Your tickets for trains and the ship are here, and the reservations are all made. Here is the money you’ll need—crowns, dollars, and French francs. Take the children as planned tomorrow morning and get them home.”[57] He told her gently, “If I don’t come back, go without me.”[58] She “was brave and outwardly she was calm, but her eyes were full of apprehension.”[59] She wondered at that moment if she would ever see her husband again.

Wally left as Martha watched anxiously for a last glimpse of her husband from the bedroom window. “I saw below me two other men waiting outside. They encircled Wally as he emerged from the house and marched him past our cherry tree that was barely beginning to bud to an official car that stood waiting beyond the gate.”[60] For the next seven excruciating hours, she did not know where he was, but he finally returned.

Much to Wally’s surprise, the Communist government granted him alone seven more days. On March 1, 1950, Wally took his family to the train station, where they were greeted by a throng of Czech members who wanted to see them off. Each member presented the Torontos with a little gift of food to eat along the way after they boarded the train. There was no luxury dining car on the train, so the Torontos were delighted by the members’ generosity.[61] Food was still severely rationed. Mel Mabey remembered losing twenty pounds during the first month and a half that he was there. He was always hungry.[62] For the Czech Saints to bring food was a real sacrifice. “As the train pulled out, they cried as they sang “God Be with You Till We Meet Again,” thinking they would never see them again.[63] As the train departed, some members ran alongside [it], expressing their farewells in…kisses and tears.”[64]

Much to Martha’s surprise, a few railroad officials and a customs agent entered their compartment on the train. They checked their train tickets and passports and then went through every little package they had been given by the members. “[They] broke open each sandwich, roll, cake or cookie to see if anyone had handed [the Torontos] some contraband. Even the apples were cut up, and all those beautiful gifts that were so lovingly prepared for [them] were left lying in a big mess on the opposite seat in the compartment.”[65] Consequently, the children were traumatized and felt violated.[66] It seemed ridiculous to accuse little children of being spies as if they could do any real damage. The officers even checked to see if anybody had hid “microfilm in the [baby’s] diaper.”[67] It was ridiculous, to say the least.

Bob Toronto was particularly upset when they took everything out of his trunk, including two big stamp books that were about two inches thick. He had spent three years trading and collecting stamps with his friends. The officers would not let him take the stamp books with him. He shouted, “You’re not going to take my stamps!” The officers threw the stamp books away. When they turned away for a moment, Bob went over to the trash and quietly picked up his books and dropped them behind the garments and suits. The officers strapped up the trunk, and Bob found satisfaction in his success at saving his stamps.[68]

After securing his family on the train, Wally returned to the mission home to put things in order. The first thing he needed to do was make sure that the last two missionaries got out. He also needed to finish a mission history and report to send to the First Presidency. The history was somewhat bulky, about three-quarters of an inch thick. He asked Elder Mabey to mail the history to Church headquarters when he got to Germany. Mabey asked him how he was supposed to carry it out. “Put it under your sweater.” But just before Mabey left the mission home, Wally received an interesting prompting. “Brother Mel, will you give that mission history and report to the First Presidency to your companion to carry.” Mabey thought the request was strange, but he did it gratefully since he felt like he “looked pregnant” with the papers in his sweater. When the two elders got to the railroad station, they inspected Mabey very carefully but never looked at his companion. The mission history and record arrived safely.[69]

After the last two missionaries departed, Wally concluded mission affairs as best as he could. He set Rudolf Kubiska apart as the acting mission president and the branch president in Prague, with Miroslav Děkanovský and Jiří Veselý as his counselors.[70] Wally planned to lead the mission from abroad. He was relieved that there was sufficient priesthood in Praha, Brno, and Plzeň to carry out what Wally would describe as their “underground plan,” which the Czech Saints would carry on for fifteen years. This plan was put in action when Wally’s seven days of extension concluded and Brother Kubiska was given the leadership of the Czechoslovak Mission in Wally’s absence. Despite the Communist restrictions on religion, the plan was to “help carry [the Church] on, and the way they [did] it is by what’s very comparable to the home teaching program of the Church at the present time. Once a week, usually on Sunday, two of the local elders go from home to home as though making a friendly visit. While somebody watches at the front door or at the window to ward off any unwanted visitor, they prepare and bless the sacrament, pass it to the members of the family who are present, teach them, . . . and then move on to the next place.”[71] With the plan and priesthood leadership in place, Wally drove his ’47 Ford out of Czechoslovakia on March 30, 1950.

When Wally left his cherished country, the border patrolman said to him, “We’re red on the outside and white on the in.”[72] The words likely comforted him greatly, recognizing the country’s unquenched patriotism. He arrived in Basel, Switzerland, where he stayed for a month as he tried to keep in touch constantly with the local leaders left in Prague either by phone or by telegram. On the date of April 6, 1950, the government declared that all public and private activities of the Church cease, possibly out of spite because it was the anniversary of the organization of the Church.[73] The Czech Communists liquidated all assets of the LDS Church in Czechoslovakia. Wally stayed on in Basel, hoping that he could run things from there, but he soon realized that he could manage just as well in Salt Lake City, so he finally went home.[74]

The decree of April 6 “eliminated the public Church, but not the one that persisted privately in the hearts and minds of its members. . . . The circumstance did little to erase the hopes of those who gathered at the Czech Mission reunion held April 7, 1950, in Salt Lake City. The group included Elders John A. Widtsoe and Ezra Taft Benson and President Arthur Gaeth, among others. These leaders knew the decree was only a delay, though it turned out to last much longer than they might have hoped.”[75]

The Communists did not stick to eliminating just their religious enemies. They continued to sift out their foes within the confines of their own offices and ministries and turned on their own whenever the situation benefitted their goals. The leader of the National Socialist Party, Milada Horáková, “was sentenced to execution by hanging on the charges of treason and conspiracy at the conclusion of a show trial in which she defended her position in spite of the scripted legal proceedings. The show trials continued as members of the government, security offices, and eventually even the general secretary of the Communist Party, Rudolf Slánský, fell victim to the purges.” The government felt that they needed “a more highly visible and powerful scapegoat to increase the political and psychological impact of the purges.” Prime Minister “Gottwald and other party leaders had Slánský arrested in November 1951.” They proceeded to torture and abuse the general secretary, both physically and psychologically, for a year. He was placed on trial with thirteen other codefendants, most of them Jews, on November 20, 1952. “Ironically, Slánský had sanctioned the purge trials in Czechoslovakia and even drafted the letter requesting that Stalin send Soviet experts, who now acted against him.”[76]

Wally’s expulsion, as well as those of his missionaries, had drawn “national headlines, chiefly because of his successful efforts to win the release of several missionaries who had been imprisoned by the Communists.”[77] The papers kept up with Wally’s grim situation as it unfolded. One headline read, “Eleven United States Mormon missionaries have been ordered expelled from Czechoslovakia, apparently in a Government drive to reduce the number of foreigners in the country.”[78] It made sense that the government was trying to eliminate foreigners. “This has been developed progressively in the last six months by continuous propaganda related to a series of arrests, trials, executions and expulsions. The Czech people are given to understand that almost all foreigners in their midst are spies and that to give them anything more than the most banal information is to risk committing treason. The facts of the country’s economic life are guarded like military secrets.”[79] When the twelfth missionary was expelled, the reason was that he represented “a threat to the peace and security of the state.”[80] This, of course, was an issue that Wally faced for years, first with the Catholics, and last with the Communists.

After Wally’s departure in 1950, many Church members were interrogated by the secret police, including Sister Zdenka Kučerová “concerning her genealogical activity, saying such information could be used to establish covers for Western spies coming into the country. Undaunted, she responded there was nothing in Czechoslovakia worth the attention of spies. Ljuba Durd’áková was interrogated with a light glaring in her eyes and was denied access to restroom facilities. While there was an inevitable attrition [in Church membership], the faithful bonded together with a sense of spiritual unity that toughened under testing.”[81]

Notes

[1] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 83.

[2] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[3] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 6–7.

[4] Dale Tingey, interview, 2.

[5] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 6.

[6] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 18.

[7] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 6.

[8] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 7.

[9] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 16.

[10] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 7.

[11] Papers found in Jiří Šnederfler papers, Europe Church History Center, Bad Homburg, Germany, copy in author’s possession.

[12] Don Whipperman, interview, October 9, 2013, 2.

[13] Don Whipperman, interview, October 9, 2013, 2.

[14] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 83–84.

[15] Ed Morrell, “Summary of Czechoslovak Archive Documents, dated in the 1940s and 1950, turned over to the Torontos in 2007,” in author’s possession, 1.

[16] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 83.

[17] William M. Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011), 198.

[18] Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 199–200.

[19] Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 200.

[20] Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 200–201.

[21] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 48.

[22] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 83.

[23] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 50.

[24] Don Whipperman, interview, October 9, 2013, 4.

[25] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 16.

[26] “U.S. Requests Data on Missing Mormons” New York Times, February 10, 1950, 14,.

[27] Don Whipperman, interview, October 9, 2013, 1–2.

[28] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 55.

[29] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 14.

[30] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 50.

[31] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 14.

[32] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 2.

[33] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 49.

[34] Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 203.

[35] Dale Tingey, interview, 1–2.

[36] Dale Tingey, interview, 5.

[37] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 2–3.

[38] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 8.

[39] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 84.

[40] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 84–85.

[41] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 84.

[42] Religious News Service, “Mormon Missionaries Mix Basketball and Preaching,” New York Times, March 1, 1949, 16.

[43] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 2.

[44] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 84.

[45] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 57.

[46] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 1, 4.

[47] Wallace Toronto, fireside in Nashville, Tennessee, 1965, transcript in author’s possession, 2.

[48] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 3.

[49] Olga Kovářová Campora, Saint Behind Enemy Lines (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 89.

[50] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 85; Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 51.

[51] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 57–58.

[52] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 85.

[53] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 56.

[54] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 58.

[55] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 85–86.

[56] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 16.

[57] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 61.

[58] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[59] Miller, “My Story: The Dream,” 16.

[60] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 61.

[61] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 61.

[62] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 4.

[63] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[64] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 85–86.

[65] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 62.

[66] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[67] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 28.

[68] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 12.

[69] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 3–5.

[70] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 86.

[71] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 2.

[72] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 21.

[73] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 4; Toronto, fireside, 1965, 2.

[74] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 66.

[75] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 86.

[76] Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 204.

[77] “W. F. Toronto Dies In S.L.,” Deseret News, January 10, 1968.

[78] “Czechs Oust 11 Mormons: Order Affects Missionaries of U. S. Church Group,” New York Times, November 17, 1949: 17.

[79] Dana Adams Schmidt, “Czech Police Said to Hold Mormons,” New York Times, February 11, 1950, 3.

[80] “Czechs Expel Twelfth Mormon,” New York Times, December 19, 1949, 19.

[81] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 87.