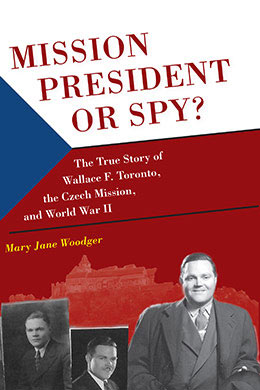

"Leader of a Spy Ring"

Mary Jane Woodger, "'Leader of a Spy Ring'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 191–208.

The situation in Czechoslovakia was, in a word, precarious when the Torontos returned home to Salt Lake City. Their experiences with Nazis and Communists had especially affected Martha for the worse. Even when crossing the ocean, she was “strongly sea sick” and could not even get out of bed.[1] When Martha and the children anchored in New York City, they were greeted by crowds of people, including reporters, all eager to know what was going on. The same thing happened when they arrived in Salt Lake City. Everyone seemed to want to get the story and a photograph of the “broken down” wife of President Toronto.[2] Arriving home, Martha was in shock after encountering so many horrifying experiences with six children. She would not get out of bed, and the children were told to not disturb her. In spite of how brave she had appeared and how blessed they all had been, she had become a very sensitive and delicate soul.[3]

On arriving home, she and the children went directly to her mother-in-law, Etta Toronto’s home, and Martha immediately went to the attic to lie down. The pressure she felt on her mission was too much for her to handle.[4] And the possibility that she would never see her husband again terrified her immensely.[5] The family called in Dr. Louis Moench to examine her. When he asked her how long it had been since she had managed to sleep, she could not remember. She had suffered a nervous breakdown. She could barely even talk. He gave her a shot, and she slept for practically three straight weeks. Only when no one was around, she crept down the stairs to get food.[6]

After three weeks, she still seemed “semi-distant. She did not really get involved with other people, at least with the family.”[7] Martha wrote that she had recovered by the time Wally had arrived home two months later.[8] However, the children remembered her illness differently. She had, in their minds, remained bedridden for nearly a year.[9] At fifteen, Marion became a mother to her siblings in many ways. To David, “Marion was more of [his] mother in those motherly ways” than was Martha in many respects.[10] By the time he had any recollection of that year, his mother had fully recovered. His chief memory of her was when she would “lovingly [put] . . . lunches together” for him. Years later, he realized that Marion really had been the one taking care of him then.[11]

For the most part, the younger children were somewhat oblivious to what was going on. Bob, who turned fourteen when they returned to America, had not truly recognized the extent of the danger he had been in. He had no idea that they were throwing the missionaries out, that his father was targeted as a spy, or that his mother was stressed to the point of emotional and physical absence. She was not really in his picture in particular while they were in Prague anyway “because she had 50 missionaries that she had to take care of, and at the end, two . . . were in some prison somewhere.” At the end of it all, “the thing that I recall is that when we did get home . . . she [looked] like she’d been dragged through a wringer.”[12]

Even though Martha gradually began to recover, she was never completely the same. Her children remembered that a lot of people in their ward thought she was “really snooty and stuck up.” Whenever they said such things to Carma, she defended her sister-in-law immediately. “Cut her some slack. You don’t know what she’s been through.” Carma observed, “I think she was just absentminded; she just wasn’t tuned in to other people. It wasn’t that she ignored them on purpose.” When she walked down the aisles at church, she looked neither to right nor to the left. She walked around everyone. “And that was just Martha.”[13]

Eventually, Wally and Martha began to share their experiences. They participated in firesides and discussed World War II and Communism, relating the many incidents they endured. When Martha took on such speaking engagements, it took her days after retelling the story to recover from the flood of apprehension and discomfort that rushed back to her. Occasionally, she ended up in bed yet again for days before she could erase all her fears and anxieties.[14]

When Wally returned home, he started looking for a job immediately. Subsequently, he ran for the Salt Lake City school board and served there for thirteen years. He became president of the Utah School Board Association and served as the chair of the board’s legislative committee. He was also president of the board of control of the Salt Lake Area Vocational School. Most importantly, however, he eventually became the director of the American Cancer Society, after which he rejoined the Salt Lake Kiwanis Club.[15] He also worked with Toronto and Company, the family business that his father and brothers ran. He helped out every once in a while with his brothers in constructing homes during the summer. He even sold houses and helped in the office as well.[16]

The brethren never released Wally as the mission president over Czechoslovakia. Instead, they asked him to remain as president in liaison with those he had left behind. The calling posed its own difficulty. The branch president in Prague was a member of the Communist Party and had not been a member of the Church for very long. Consequently, Wally struggled just to keep in contact with him and fulfill his duties as a liaison to the best of his ability.[17] He did, however, find it easy to faithfully keep in touch with his returned missionaries. He was adamant that none of them go inactive. He attended their homecomings and their marriages. “He was an eternal friend, not just a mission president.”[18] One of his missionaries was of particular interest—Ed Morrell. Wally and Martha pushed for Wally’s sister, Norma, to get together with Elder Morrell. The two had known each other but had never dated. For their first date, the Torontos had the two of them to dinner one Sunday. They “decided to marry on [their] second date, were engaged privately for two months, and wedded a month after.”[19]

Wally gathered his former missionaries every month or two. As many as could would meet with him. They held mission reunions in Salt Lake City during every general conference until Wally died. For a while, even some of the pre–World War II missionaries attended. The elders “formed a kind of compact together. . . . [Wally] helped us to love each other.”[20]

At Christmastime, Wally and Martha gathered the children around the dining room table to stuff envelopes with Christmas messages for the Church members in Czechoslovakia. The messages were “pretty innocuous. There was no real talk of Christ. There was no real talk about religion” in general.[21] David remembered, “Those Christmas letters . . . were very generic, just enough to let them know we were thinking about them.” The Torontos simply conceded to wishing the Saints, “Happy Holidays.” The members addressed their return letters to Martha Sharp (Martha’s maiden name), rather than Wally or Martha Toronto, to keep their letters from being confiscated by the Communists. The members in Czechoslovakia used all kinds of codes in the letters so they could communicate to the Torontos what was happening. The members included stories like, “Kilroy was here,” or, “Uncle Kilroy came and . . . they had some good discussion.” It really meant that a Church member was interrogated severely, but everything turned out okay.[22]

Because stuffing envelopes took so long, the Torontos started the process in November of each year. Though it was not much, it did provide one way for Wally to stay in touch with the members. Along with the letters, they sent care packages with food and chocolate; however, those items never arrived. In fact, the Communists frequently confiscated both the packages and letters. Wally had to be very careful about what he wrote and sent. Fortunately, the Church eventually began to supply funds for coupons that the members of Czechoslovakia could use in the export store in Wenceslas to buy shoes, clothes, and other items that were unavailable in any other store.[23]

Life eventually began to take on some vestige of normalcy. Wally was always “very curricular. He loved being with people.” On the other hand, Martha just needed to “have a chance to dress up.” She was not a shallow person, according to Carma. She just became “tired of people . . . and wanted to do what she wanted to do.” She “loved the symphony, she loved ballet, she loved going out to dinner.” In fact, she and Wally joined what seemed like “a hundred thousand dinner groups.”[24]

During the 1950s, visitors from Czechoslovakia began trickling to the Toronto home. Some were people who had escaped the Communists. Others were Czechoslovakian dignitaries visiting Salt Lake City. Because Wally knew the Czech language and people so well, he was always asked by the Church to be their escort, and Czechoslovakian people often contacted him when they were in town. David remembered going with his dad to the Bingham Copper Mine one time and showing a Czech government official around the city.[25]

Even though he was in Salt Lake City, Wally Toronto held the Czechoslovak Mission together from thousands of miles away.[26] “For nearly fourteen years, the Czech membership kept their faith in silence, unable to worship publicly or to enjoy any type of regular contact with the Church beyond the Czech borders.”[27] From his home in Utah, Wally provided whatever assistance he could. He sent financial aid, clothing, medicine, and Church publications. And though the Saints were isolated, they continued to save their tithing. Wally was certain that such a sacrifice played a role in preventing apostasy.[28]

Apart from being the de facto mission president of Czechoslovakia, Wally served in other Church callings in his home ward and stake. His assignments included membership in several committees, such as the M Men, Special Interest, and Ensign committees. He served in the leadership of the Parleys Stake high priests quorum. He was a Gospel Doctrine teacher in the Parleys Fourth Ward, an Aaronic Priesthood adult general secretary, and a priests quorum adviser.[29] He participated on the general board of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association in 1950 and served in that capacity until 1964, traveling extensively. In the same year, “the General Board of the Mutual Improvement Association appointed Wallace Toronto to visit Switzerland. . . . [Wally] sent his passport to Swiss Mission President John Russon in advance, hoping that Russon might get a visa for him to cross the border into Czechoslovakia. Permission was denied.” That same year, the country granted permission for Czech Latter-day Saint Marie Vesela to visit the United States.[30]

It would be Marie’s visit that would bring about Wally and Martha’s return to Czechoslovakia. Marie Vesela, who had served as Wally’s personal secretary in Prague, came to Salt Lake City at the invitation of her sister for three months. Her sister had married Joe Roubíček, “a young man who had acted as mission president during the war years [keeping] the mission together as much as possible.” He later moved to Midvale, Utah, in 1949. “He and his family were some of the very few who had ever left a Communist country legally. They waited a long time, two years, for permission and visas.” When they had settled in Midvale, they sent a letter asking if Marie could visit them in America. “The new regime was reluctant to let young and strong people leave” Czechoslovakia. In fact, they “avoided it at all costs.” But “the Lord was on their side,” and somehow permission was granted.[31]

One of Marie’s requests while she was in Utah was to meet President David O. McKay. Wally arranged the meeting, which Vesela said was “the highlight of [her] life.”[32] The discussion that ensued shaped the future of the journey that the Toronto family had yet to commence. President McKay asked Wally, “How is it that this woman can get out of the country and visit here for three months?” Wally explained that:

Czechoslovakia at this particular time was on the brink of economic ruin. “They will do anything to get foreign exchange. Their whole economy at this time depends on money from other countries. English pounds and American dollars are particularly sought after because of their stability on the economic market. This woman’s fare was paid, in dollars, to the travel bureau in Prague, not only one way, but her return fare also. They haven’t softened their hearts any—they just want money, and at this particular time they are encouraging tourists from anywhere to come and spend money in their country.”[33]

President McKay then questioned, “Brother Toronto! If this is the case, why would they refuse you a visa into that country?” Wally replied, “President McKay, I am still considered a threat to the peace and security of that nation, and money or not, I don’t think they would let me in, not with my record. In their eyes I am still the leader of a spy ring, and they are not about to let me do it again.” To this, President McKay countered, “Our members need you at this time. They have been carrying on underground long enough. They need the authority of their mission president. I advise that you and Sister Toronto go home, make application again, and if it’s the Lord’s will, He will open the way. If you get a visa, we will send you as soon as you can get ready.”[34]

The Torontos were stunned with President McKay’s instructions. For a decade and a half, they had been on American soil. “Ever persisting during the next fifteen years, [Wally] applied nine times and received nine refusals for a Czech visa.”[35] After nine failed attempts, they were to try once again. Halfheartedly, they went through the same routine of obtaining passports and sending them through the proper channels to the Czech Embassy for their visas. They “made no plans, nor did [they] anticipate any journey. [They] had done this too many times to get excited.” Much to their surprise, the passports came after just one week of waiting, granting them a visa for fifteen days in Czechoslovakia. As Martha put it, they “nearly exploded with excitement,” but they also had “mixed feelings” at the possibility of jail time or being held at the border.[36]

The Torontos paid for all their reservations for hotels and planes in advance, as required by the Czech government. Wally and Martha were both very excited at the prospect of seeing their people again. They could barely sleep at night from “the excitement and anticipation.”[37]

Before the Torontos departed, President McKay placed his hands upon Wally’s head and gave him a blessing. In it, he promised that Wally would be inspired by the Lord to accomplish what was necessary “for the good of the mission and necessary for the morale of our members, who were by this time feeling the oppression and discouragement of a downtrodden people.” He blessed him that we would go safely into the country and come back out without bodily harm or undue detention. He set him apart once again as president of the Czechoslovakian Mission and told him that we would travel safely by land, sea and air to accomplish the desires of his heart. “Satan, himself, is at the head of the vicious men who banished you from Czechoslovakia,” President McKay stated in the blessing.[38]

President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency then blessed Martha, saying, “We seal upon you the blessing of peace, tranquility and confidence. May you both be wise under the inspiration of the Holy Ghost. Take no action that would bring any condemnation or criticism from government officials, but go quietly about your work and, without stirring up any ill feeling or turmoil, leave a blessing with those people.”[39]

The Torontos flew to Vienna on December 30, 1964. They rented a car and began driving first to the embassy to report their visit. The drive was “picturesque” as they traveled the countryside. However, “the tranquility of the scene soon changed as [they] left the Austrian border station and approached the Czech station nearly a half mile ahead.” Wally asked Martha to pray for the Lord’s blessing as they drove down the “narrow strip.”[40] She prayed that God would “soften the hearts of those men at the gates who were all armed with machine guns, and especially those in the border station who would be the final decision makers about [them] entering [the] country.”[41]

The guards hesitated for quite some time as they examined the passports. But in the end, they let them through, and the Torontos passed through three separate gates, parked the car, and went into the border station building. When they left, Martha noticed, “On either side of [the] clearing were high entanglements of barbed wire, high enough and thick enough that an escapee could not possibly get through. If he did, he took the chance of being attacked by a vicious dog or shot by one of the guards before he crossed the clearing. The whole country of Czechoslovakia was surrounded by this barrier—not to keep people out but to keep them in, as it formed an immense concentration camp.”[42]

A “new wave of fright” washed over Martha as they entered the building. They were met by uniformed officers, who spoke to them in English. The Torontos declared their valuables, cameras, typewriter, and money. The guards were naturally interested mostly in the large amount of money that Wally received from the First Presidency not only to impress the guards, but also to help the people in the Czech Mission. While Wally and Martha waited on a bench, the guards took their passports into the inner office. The Torontos were “holding hands and praying inwardly that they wouldn’t open the ‘black book’ and see Wally’s name on the top line of ‘undesirable characters.’”[43]

Though Wally had been expelled from the country and had been gone for nearly fifteen years, he was still considered a leader of a spy ring. His picture was “flashed on the movie screens, and it was posted up in the post offices as being one of the dangerous capitalistic spies within Czechoslovakia.”[44] Martha recorded:

If [the guards] did look in the “black book,” they passed it over or the Lord blinded them as they looked. Perhaps the thoughts of us spending all that money was too much to let them refuse our entry. President McKay had said, “If dollars will get you in, and it is obvious that is what they want, we will give you plenty to show them.” They gave the permission, looked in the trunk of the car, but didn’t open any suitcases. We had made sure there would be no printed matter, list of names, or church literature that would incriminate us in our attempt to enter the country. As we drove off, leaving the reminders of a police state behind us, the feelings of fear or apprehension that had been so constantly with me melted away.[45]

Wally added that before they reentered Czechoslovakia, they had received a blessing from “President McKay [which said] ‘you will cross the border without difficulty, you will go in and you will do your work, and you shall have influence with the leaders . . . you shall come out without difficulty,’ we crossed the borders in just 20 minutes.” Other tourists were held in customs for many hours, and Wally was reminded again “of the great concentration camp Czechoslovakia [had become].”[46]

With gratitude in their hearts, the Torontos drove to Brno. They were sure that Sister Vesela had told other Church members that they had secured visas and were going to be there. Word of mouth was the only way they could inform members about their visit ahead of time. The Torontos expected to find Brother and Sister Vesela but were not expecting the crowd that greeted them. There was a law in place requiring that no more than five people could meet in one place at the same time. But the Czech Saints in Brno “had learned to be very clever in skirting the law if they wanted something bad enough, and [the Torontos’] visit was important to them.”[47]

That evening, Brno members shared their experiences “of the fourteen years that had intervened since their last acquaintance.”[48] As they were serving the Torontos a delicious Czech meal they had prepared, the doorbell rang. Everybody feared that it might be the police. The Torontos had parked their car far away from the house as a precaution, but they were still apprehensive. When they opened the door, they were relieved to see an older woman who had made a habit of visiting the branch president, Brother Vrba, regularly. The branch president said nothing to the woman as she entered his house. He let her figure out what was going on by herself. When she saw Wally and Martha sitting there, she turned white as a ghost and began trembling, overcome by emotion. She pointed to them and asked Brother Vrba, “Is that Brother Toronto?” His reply was music to her ears as he affirmed that it was indeed. Wally put his arm around her shoulder, and she burst into a flood of joyful tears as she embraced him. Still trembling, she moved to Martha, who stood to greet her as the sister kissed her cheeks. Over and over, she repeated, “I never thought I’d ever see you again. How is this possible?”[49]

The next fifteen days were filled with similar experiences as the Torontos traveled from home to home, taking local priesthood leadership whenever possible.[50] The only warning members would receive was a phone call an hour before the Torontos arrived. At the sight of their beloved mission president and his wife, tears came freely and the Saints cried with joy. Martha remembered that they all went up to them “at once to kiss and embrace [them].”[51] As they went from home to home, “Wally’s main concern was to bless those who were in need of the Lord’s blessing. Many were sick and found great comfort in their president being able to administer to them.”[52] Some members would look at him with tears in their eyes and ask, “Why are we going through this? Why are we suffering like this?” Wally would answer, “It’s because you’re going to be witnesses.”[53] After each day, the Torontos returned to the same hotel at night, unable to sleep because of their overfilled stomachs from the generosity of the Czech Saints. They visited Martha’s Beehive girls, who were by then married, and the young men, some of whom were ready for ordinations to new priesthood offices.[54]

The Torontos learned that the priesthood brethren still operated their underground plan and visited members in their homes on Sunday to deliver the sacrament. They taught the gospel “to one family at a time.” In an effort to be extra cautious, they regularly altered visiting assignments and only stayed for twenty or thirty minutes at most to avoid arousing suspicion.[55] They were especially careful when the Torontos were present since “any attention [given] to Americans or Mormons” meant imprisonment or terrible harassment. But it remained a challenge, nevertheless, because they had to work faithfully yet stay undetected. By 1964, the Saints were used to functioning underground in such a way.[56] Wally found that “not more than two percent of our entire membership [had] been lost to apostasy. . . . This is remarkable and certainly shows what a home teaching program can do when the gospel is taught in the home and with regularity.”[57]

In large metropolitan areas like Prague and Brno, members lived many miles apart, and the brethren would have to travel by streetcar to reach them. They did not use their own vehicles. The Torontos had to be very careful about where they parked their car on the streets. Czech citizens were required to report to the officials if they saw a car with a foreign license plate. When a visitor went to the border to leave the country, the Communists knew exactly where they had been. It seemed like the government knew everything, “what you spoke, whom you . . . called in your hotel, everything.”[58] If a citizen even spoke with a foreigner, they had to report it. Consequently, the Torontos had to stay in hotels rather than with members so the police would know where they were at all times. If they planned on going to a surrounding town to visit members, they always made sure to be back in Prague by the end of the day, even if that meant traveling a long way very late in the evening. They were also required to leave their passports at the hotel desk at night in order for the secret police to check them as they made their rounds at the hotels and, therefore, keep track of all foreigners.[59]

As soon as they entered the country, Martha found that her ability to speak Czech returned easily, just as promised in the blessing she received from President Brown. He promised that “once she got into the country, she would have the gift of language.”[60] Members told her, “You speak as well as you did when you were here fifteen years ago.” They said that Wally spoke as well as a native, except that it was not quite right. His accent was a little off. Because meetings were prohibited, they visited members one-on-one. Wally would put his arm around the members as he talked to them. There were only six or seven hundred members at the time in the country.[61]

Czechoslovakian member Olga Kovářová Campora remembered hearing about what had happened during the Toronto visit in December 1964. A number of Czech members and their families had been questioned and persecuted. Many had to leave the country as a result. A lot of members who stayed behind had only pictures of their sons and daughters who lived outside of Czechoslovakia. “These pictures were their entire [treasure], their life and hope. Those photos were often the only connection they had with their families [who had left the country]. Sitting among these old members felt like sitting under a beautiful tree, surrounded by long branches which gave you peace from the sharp world around you. . . . Communist oppression was a fact of their lives that had left certain marks but didn’t change their faith a bit. Sometimes it seemed their lives were stopped in the middle, and they were left only with their faith to work through to the end of their lives.”[62]

Gad Vojkůvka took Wally and Martha to visit members in Praha, Mladá Boleslav, and Bakov. “This was a wonderful experience. I saw the joy of members, heard their testimonies, and heard the [advice] and support given to them by President Toronto.”[63] During Wally’s absence, the Saints had rejoiced with every piece of news, every card, and every letter that he sent from Salt Lake City. Those “shards of the Lord’s light that came to their houses as a miracle would be cherished.” They generated so much joy, not just for weeks but for months and years.[64] And then Wally was actually there in person.

On New Year’s Eve, the Torontos decided, “The most important thing for us to do would be to see each of our members, if possible. Their morale was very low after fifteen years of servitude and oppression, and a visit from us would be like a shot in the arm for them.” Before the country banished him, Wally had appointed several local men to leadership positions to take care of the members in his absence. He assigned, for example, “a brilliant and vibrant man”—Brother Vrba—to be the branch president in his area. Brother Vrba had “run the affairs of this branch in a manner that was most pleasing to Wally.”[65] Nevertheless, some members had “become disgruntled with the local leadership,” even with the men who Wally had appointed. After some discussion, it was decided that the local leaders would go with the Torontos on their visits. Wally always made it a point to declare to the Saints that the appointed leaders were appointed by the power of the Lord, that they were to lead them during his absence.[66]

Wally did, however, make some changes in the branch presidencies while he was there, setting brethren apart to certain positions and calling others to replace those who had died or moved away. However, it was not his main purpose. From the beginning of their journey, both Wally and Martha had a feeling that the Lord had a particular reason that they go back to Czechoslovakia, but they were unsure of what it was initially. As they visited with members, Wally was led to tell many of them a message from the Lord:

Brethren, your calling in the priesthood is far greater than you can ever imagine. . . . In the providence of the Lord, an iron curtain cannot be rung down on His gospel, cannot be rung down on the Priesthood. You brethren are still His representatives. You still speak for him in spite of the fact that I’m not here and that missionaries are not here and that you don’t have direct contact with the President of the Church. . . . And when the time comes, brethren, if you live faithfully from here on out, continue to uphold the principles of the church, keep close to the Lord in prayer, and manifest and exercise your priesthood to the best of your ability, the day will come when you stand before the bar of God and ye shall testify of all the terrible things that have happened to your nation. . . . You’ll also testify of, then, the blessings the Lord has given those who have remained faithful to the covenants.[67]

The brethren responded amiably, expressing joy that they finally “realize[d] and recognize[d] what [their] responsibility and part [was].”[68] Through this and other visits with members, Wally and Martha finally realized that one of the Lord’s reasons for sending them back to their mission field was, as Martha explained, that “our people needed us, and seeing us in person was a great morale booster for them. And we knew the Lord was protecting us, too, because we were not detained anywhere and were never approached by the police nor were we followed. But we knew that they knew we were there and what we were doing. As long as we were not bothered we just kept going as fast as we could in order to accomplish what the Lord sent us to do.”[69]

Beyond visiting members, Wally had some other specific visits he intended to make: the Ministry of Interior to push microfilming of Czech genealogical records and the oncological hospital to build strong, goodwill relationships with the doctors there. Wally felt successful on both fronts stating, in regards to their success with the genealogical progress, “We believe that we pushed the door open at least for the microfilming of the genealogical records in Czechoslovakia. This was one of the achievements that we at least got started.” As for the hospital visit, Wally discovered that the Czech doctors were far behind the United States in every aspect of cancer control. Wally “promised to send them films and literature and subscriptions to professional cancer magazines.”[70] He followed through on his promise, and the Czech doctors expressed much appreciation for his generosity.

As the Torontos prepared to leave Czechoslovakia, Brother Vrba turned to Martha and asked that she tell President McKay something for him. When she replied that she would love to, he said, “I want to thank him for sending you along with your husband.” She inquired, “Why is that?” His answer touched her deeply: “Because you have been an example to our women. Our wives are afraid and won’t let us go when we have assignments. We know there are dangers, but now they have seen you, and your assignment with your husband has been far more precarious than ours, yet you have gone with him under very trying circumstances, and they have seen how you share in the priesthood.” Martha was overcome with his kind words and promised to tell the prophet when she and Wally returned to Salt Lake City.[71]

After they returned home, the Torontos “read over the blessings [that] had been given [them] by the First Presidency and were astonished by the prophetic nature of these promises. Every item mentioned in the blessings had come true.”[72]

Notes

[1] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[2] Anderson, Martha Sharp, Letters to Wallace Toronto, Church History Library, April 4, 1952, 1.

[3] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[4] Judy Richards interview, 2.

[5] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 7.

[6] Carma Toronto interview, February 26, 2004, 7, 11.

[7] Carma Toronto interview, February 26, 2004, 7.

[8] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 67.

[9] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards interview, May 3, 2013.

[10] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 7.

[11] David Toronto, interview by Daniel Toronto, 2010, transcription in author’s possession, 8.

[12] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 6.

[13] Carma Toronto, interview, February 26, 2004, 8.

[14] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 8.

[15] “W. F. Toronto Dies in S.L.,” Deseret News, January 10, 1968.

[16] Albert Toronto Family Organization, “Story of Albert and Etta Toronto,” 2.

[17] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 14.

[18] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 16.

[19] Morrell, “Summary of Czechoslovak Archive Documents,” 2.

[20] Mel Mabey, interview, August 13, 2013, 16.

[21] David Toronto, interview, Daniel Toronto, 2010, 1.

[22] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 28.

[23] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 9.

[24] Carma Toronto, interview, February 26, 2004, 9.

[25] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 9–10.

[26] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 15–16.

[27] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 51.

[28] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 16.

[29] “W. F. Toronto Dies in S.L.,” Deseret News, January 10, 1968.

[30] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 88.

[31] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 75–76.

[32] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 75–76.

[33] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 76.

[34] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 76–77.

[35] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 51.

[36] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 77.

[37] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 70.

[38] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 79.

[39] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 82.

[40] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 10; Anderson, Cherry Tree, 82–83.

[41] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 83.

[42] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 83.

[43] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 84.

[44] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 3.

[45] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 84.

[46] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 3.

[47] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 86–87.

[48] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 90–92.

[49] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 89.

[50] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 4.

[51] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 87.

[52] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 93.

[53] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[54] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 90.

[55] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 90.

[56] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[57] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 4.

[58] Johann Wondra, interview, May 30, 2013, 4.

[59] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 91.

[60] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 7.

[61] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 10, 16.

[62] Campora, Saint Behind Enemy Lines, 78.

[63] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 4.

[64] Campora, Saint Behind Enemy Lines, 79.

[65] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 88.

[66] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 91–92.

[67] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 6.

[68] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 6.

[69] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 93.

[70] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 5.

[71] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 94–95.

[72] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 95.