"Immersing Himself in Bohemian Life"

Mary Jane Woodger, "'Immersing Himself in Bohemian Life,'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 17–28.

In the 1920s, serving as a full-time missionary was an exception for young LDS men, not a rule. One had to be asked to serve a mission by his priesthood leaders. Unlike today, a young Latter-day Saint did not just decide to go; rather, others made the decision. In the summer of 1928, Wallace F. Toronto received a letter from Box B (the address of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) calling him to serve in the German-Austrian Mission. And so, Wally, in the great tradition of his grandfather, Joseph, and his father, Albert, accepted the call to serve as a missionary.

Typical of many missionaries, Wally left a girlfriend at home. Her name was Dolores. The two had been dating for some time before Wally received his call. They agreed to write each other often once he entered the mission field in Germany. Saying goodbye was not easy.

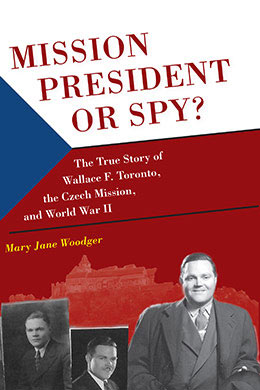

Wallace F. Toronto, 1928. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Wallace F. Toronto, 1928. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Wally arrived in October of 1928, at the mission headquarters in Dresden.[1] Like his father, he found that the German language came easily. Later, Wally wrote in third person about the first year of his mission experience in his master’s thesis: “In October of 1928 he located in Germany, and there during almost a year’s stay attempted to learn the German language and to acquaint himself with the social customs and behavior of the people. This proved to be a most enjoyable and profitable year for it gave him an insight into the life and culture of a people, who, prior to this time, were known to him largely by name only. He enjoyed their hospitality and goodness and insofar as he was capable became one of them. He learned to love the common folk and admired them for their sincerity.”[2]

Wally soon grew accustomed to the different aspects of missionary life, including distributing missionary pamphlets (tracting), giving speeches, studying, visiting members and investigators of the Church, learning to live with a companion, and dealing with homesickness. In one of his journal entries from four months into his mission, he provided a small glimpse into the daily life of a missionary. “Visited a number of favorable prospects and invited them to attend our meeting. We were called upon today to administer to two sick kiddies. I think they have whooping cough. The parents are not members of the church. It was the first time for both Bill and I. I did the anointing. The Priesthood is a wonderful gift. Had a fine spirit in our meeting.”[3]

After Wally had acquainted himself with the German people for a year, he was transferred, not from one town to another town, but from one nation to another.[4] The catalyst was a request to President Heber J. Grant by Františka Vesela Brodilová, who was born in 1881 in southern Bohemia. When her mother died, eighteen-year-old Františka moved to Vienna, Austria, to live with an older sister. There, Františka married Frantisek Brodil in 1904. In 1913, she learned of the restored gospel and was baptized in the Danube River. In 1919, due to World War I and other situations, the family moved to Prague. Shortly thereafter, her husband passed away.

In Prague, she had no contact with the Church. Despite Františka’s diligent efforts and prayers to bring the gospel to Czechoslovakia, years passed without Latter-day Saint missionaries entering Czechoslovakia.

After more than a decade of praying for missionaries to come to her country, “Františka felt impressed to write to the First Presidency. . . . To [her] great joy, her letter to President Heber J. Grant got immediate results.”[5] In that same year, Wallace F. Toronto was called on his mission to Germany. Under President Grant’s direction, Edward P. Kimball, president of the German-Austrian Mission president, was asked to choose his strongest missionaries and send them to Czechoslovakia in June of 1929. Among them was Arthur Gaeth. Elder Gaeth had attended “the Priesthood Centennial of the German-Austrian Mission in May 1929.” While there, John A. Widtsoe, president of the European Mission, said he wanted to call Arthur on a special mission. Arthur felt inspired that he would be going to Czechoslovakia because his mother, a Czech, had a promise in her patriarchal blessing that he would “take the Gospel to her native land.”[6] Gaeth was called as the president of the Czechoslovak Mission along with five other missionaries: Alvin Carlson, Wallace Toronto, Charles Josie, Willis Hayward, and Joseph Hart.[7]

First Czechoslovakian missionaries with Arthur Gaeth (center) and Wallace Toronto (seated on far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

First Czechoslovakian missionaries with Arthur Gaeth (center) and Wallace Toronto (seated on far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

The Church obtained permission from the Czech government to allow missionaries to preach the gospel in Czechoslovakia and set out to send elders to the newly opened nation. There were only seven members in the country at the time, two of which were the Brodil sisters. Only a few weeks after Wally arrived in the country, Elder John A. Widtsoe of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles dedicated Czechoslovakia for the preaching of the gospel on July 24, 1929.[8] The site was beautiful and full of the Holy Spirit as the leaders and missionaries gathered at a magnificent castle. They found a nearby wooded knoll suited for the dedication. The morning started with rain, but by the time they got to the hill at 8 o’clock in the morning, the weather had cleared for the dedicatory prayer.[9]

After the dedication, Arthur Gaeth was called as the mission president, even though he was still unmarried. In November 1929, Elder Widtsoe introduced President Gaeth to his future wife, Martha Kralickova. Two years later, Gaeth baptized and married her.[10] They purchased a villa in Prague, which became the new mission home. To get the word out about the presence of the new religion in Czechoslovakia, President Gaeth relied upon an acquaintance that had contacts that worked with Prague Radio. Two broadcasts aired, on August 3 and August 7, 1929, informing the small nation that “the Mormons had opened a mission in Czechoslovakia.”[11]

In addition to the broadcasts, Gaeth had scheduled a lecture to be given at a German adult-education institution and written an article for a German-language newspaper about the Church’s arrival in Czechoslovakia.[12] Wally came to recognize that the newly appointed president had quite a journalistic disposition and a booming voice.[13] Indeed, seventy-two articles appeared in newspapers about the Mormons within the first six months that they were there. Many of the articles were favorable. However, once they sent missionaries into Mladá Boleslav a couple of years later, “Catholic priests . . . filed police complaints . . . accus[ing] the missionaries of being ‘immoral and undesirable’ aliens and charged that ‘Mormons are a sect forbidden in every state outside of Utah because of polygamy.’”[14]

President Gaeth sued the priest for libel. Luckily, the mission president had friends within the office of Tomáš Masaryk, the president of Czechoslovakia, and they were able to settle for a retraction in the paper. A year later in 1935, the Prague Catholic newspaper “claimed that the missionaries were German espionage agents.” The statement could have generated dreadful and jeopardizing consequences. Once again, President Gaeth sued the paper and won. The paper then not only had to publish a retraction but also had to pay for court costs and give money to charity.[15] By 1931, a total of 250 articles, mostly written by missionaries, had appeared in the newspapers and journals.[16]

Wally found that the people of Czechoslovakia were different than those he had known in Germany. In his thesis, he expounded on the character of the Czech people after discussing how advantageous it was to truly “immerse himself in Bohemian life,” just as he had in Germany, in order to learn about the new people and about their characteristics and attitudes toward life. “He found that they were great lovers of individual freedom, and that in this respect they emulated the great reformer, John Hus; that although there was a feeling of distrust and antagonism toward the German nation, yet there prevailed a spirit of tolerance for the German and other minorities within the country.”[17]

Wally experienced a wonderful blessing during the second year of service when he had become one of the first elders to master the Czech language. But even more exciting to him was that his younger brother, Joseph, was able to join him in the Czechoslovak Mission.[18] At the time that Wally left on his mission, Joseph had been helping their father with a construction business and saving money for his own mission. The business prospered, and Joseph planned to leave the following year. Unfortunately, while Wally was abroad, the stock market crashed in September of 1929. The Great Depression years were filled with heavy financial reverses for their parents. Having two boys on missions only yielded additional difficulties for the Toronto family. When buyers could not make their payments to Albert, he could not pay for materials. People were declaring bankruptcy left and right. Albert could have done the same, but he would not. He paced back and forth in his room, asking himself, “How do I get out from under this?”[19]

The family chose to put their faith and trust in the Lord and knew he would provide for their needs in one way or another. The Depression often pushed people to desperation and pitted family members against each other. At one point, “the boys’ bonds and insurance policies were cashed in to pay off a loan from a demanding relative.”[20] But despite the challenges at home, the elders managed to remain on their missions. The boys “wanted to be there, to be in the mission field during the depths of the Depression. And how they ever managed to keep them there, was a real miracle.”[21] Albert eventually went to President Grant, hoping for a loan to fend off the collectors he owed. To his great joy, the prophet graciously helped him.[22]

During the crisis, Etta continued to sustain her husband faithfully. She reassured him, “Albert, we can do it. . . . Hang in there.” Because of her support, he often told Wally and Joe, “I haven’t been very smart in this life, but boys, the smartest thing I ever did was to marry your mother.”[23] Managing their finances nevertheless remained incredibly difficult for the Torontos while the boys were in Czechoslovakia. However, they felt that their ability to make ends meet was a direct result of the blessing that Grandfather Giuseppe received at the hands of Brigham Young.[24]

Joseph finally arrived in Eastern Europe near the end of 1930. He was called on a mission to Germany and arrived in Dresden on November 30. A week and a half later, on December 10, President Gaeth sent a letter to Joseph asking him to join the mission force in Czechoslovakia. Joseph had previously mentioned in a letter to Wally that he would love to serve with him, but Wally did not think it was possible. As he traveled to Prague to meet Joseph at the station, Wally was thrilled to see his brother again. They had not seen each other in over a year.[25] What a joy it was for the two brothers to serve together in the same mission!

The two brothers attended a joint Mutual Improvement Association meeting the evening Joseph arrived. Everyone present joined in singing “The Holy City.” Joseph bore his testimony in German because he did not know Czech. When he returned to his apartment, he and Wally caught up on how the family was doing and, of course, discussed the girl Wally left back home. Wally told Joe that Dolores had written and told him that “she never thought it would be possible for her to care for someone as she [did] for him, but a new feeling [had] entered her life.” The “new feeling’s” name was Tony Middleton. “Things will turn out all right,” Wally assured mostly himself, but his worry about Dolores’s “new feeling” did not go away.[26]

Joseph described in his personal history the experiences he had tracting with his brother. He recorded, “The only way I could manage that first morning was to, with one hand, give the pamphlet to a lady and hold the type-written card in the other. How I murdered the language that morning! A few were patient enough to hear me. One young woman said, ‘Perhaps you speak better German than Czech.’ Speaking in German, I told her we were missionaries from America. She then said in perfect English: ‘Well then, let’s speak English.’ Czech, German, and English at the same door! And what a thrill it is to go tracting with my own brother!” But typical of many siblings, Wally took advantage of having his younger brother as a companion and constantly teased him during their meetings. One time he jaunted, “Here am I walking the road of salvation, and there is my brother struggling in the pitfalls of sin. What can I do to help him?” Wally pointed at Joe and enjoyed the expected laughter of his audience. Then he asked his little brother to prepare a lesson for the next meeting the following Tuesday on “The Injurious Effects of Sin,” encouraging him to speak from experience. Joe later wrote, “What would you do with such a brother?”[27]

Wally worked hard throughout his mission, constantly growing in the love he had for the people he served. He was called to leadership positions and fulfilled other important responsibilities as they were given to him. On September 1, 1929, Wally recorded, “I was appointed as secretary of our new mission. Not so much to do now, but we have faith in the future.” A couple weeks later, he wrote, “Memories come again. It’s a wonderful life with all of its diversities. A man can’t read his future one day ahead. Made a list of important city officials and other prominent men and mailed them all an invitation to attend our English lectures.”[28]

By October, the mission had obtained permission from the police to distribute two Czech-language tracts presenting the Church’s doctrine, even though most of the missionaries could not yet speak the language. The tracts were the first two of twenty-five published during the first three years of the mission’s existence. They consisted mostly of translations from works authored by Elder Widtsoe.[29] Later, Wally also wrote some of the content himself. Joseph once memorized a tracting speech that Wally had written for him. By the end of 1929, Wally could already see the progress of the newly formed mission. He wrote, “The Lord certainly is good to us. There are only six of us here, but how many friends we seem to have. We have been invited out almost every night. Yes, we are beginning to get into the homes, and our friends are asking about our message.”[30]

Wally was positive, confident, and full of energy. Yet he was humble and recognized the Lord’s hand in the work. He recorded in his journal, “My heart rejoices in the work of the Lord. How diligent and how humble we should be, and yet how weak we really are!”[31] Two weeks later, he wrote, “Speaking of weather, . . . it could not be more ideal for this time of the year. Sunshine, clear sky, birds, and golly, Spring is in the air. The Lord certainly has been good to us, for we have met with great success. The Czech language is difficult, but despite it, I have felt the Spirit of God in my work as never before. The mission will succeed, for God leads it on.”[32]

Wally could not help but observe the tense political situation of the country. He noted multiple times the conditions and problems that he thought might arise if difficulties continued. “Again the people congregated and broke store windows in which were German signs. They cannot look far enough ahead to see the ultimate results—such as war and strife. It looks serious. Those papers which urged the people on are now begging them to stop.”[33] Five months later, he recorded, “Went to Brodils in evening with brethren and had Sister Jane assist me with talk. Communist’s Day. Streets are thronged with people and lined with soldiers and policemen. But no unrest is evident.”[34]

Later, in his master’s thesis, Wally discussed how the character of the Czech people translated to politics: “He noted in them strong traits of obedience to leadership, and sometimes almost blind devotion to a cause. For the most part they were seemingly non-militaristic, but greatly enjoyed talking about the efficiency and precision of the former army. Many of them were disturbed and dissatisfied about conditions and hoped for leadership which might again weld them into solidarity. Some saw the salvation of the country in the National Socialist Party, which was constantly gaining power. Others wondered about it. A few had grave doubts.”[35]

After three and a half years, it was time for Wally to return home. President Gaeth wept as Wally gave his farewell address to the Saints in Czechoslovakia in sacrament meeting the Sunday before he left. The mission president and both Toronto boys helped Wally pack his trunk at three o’clock in the morning. They then traveled to the train station and said their goodbyes, and Wally went home.[36] Little did he suspect that in three short years he would return.

Notes

[1] Joseph Young Toronto, Forever and Ever: The Life History of Joseph Young Toronto, ed. Shannon Toronto (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1996), 47.

[2] Wallace F. Toronto, “Some Socio-psychological Aspects of the Czecho-Slovakian Crisis of 1938–39” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1940), 6.

[3] Wallace F. Toronto, journal, February 5, 1929, 44, Church History Library (hereafter Toronto, journal).

[4] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview by Mary Jane Woodger, May 8, 2013, Provo, UT, transcript in author’s possession, 3.

[5] Ruth McOmber Pratt and Ann South Niendorf, “Her Mission Was Czechoslovakia,” Ensign, August 1994, 53.

[6] Kahlile B. Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002), 46–47.

[7] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 49.

[8] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 48–49.

[9] Kahile Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” Ensign, August 1994, 48.

[10] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 48.

[11] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 47.

[12] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 47.

[13] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 48.

[14] Kahlile B. Mehr, “Enduring Believers,” Journal of Mormon History 18, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 127.

[15] Mehr, “Enduring Believers,” 127.

[16] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 48.

[17] Toronto, “Some Socio-psychological Aspects,” 7.

[18] Toronto, Forever and Ever, 60.

[19] Albert Toronto Family Organization, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 45.

[20] Albert Toronto Family Organization, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 16.

[21] Carma Toronto interview, February 26, 2004, 2.

[22] Albert Toronto Family Organization, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 45.

[23] Albert Toronto Family Organization, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 45.

[24] Carma Toronto, interview, February 26, 2004, 2.

[25] Toronto, Forever and Ever, 47, 60.

[26] Toronto, Forever and Ever, 72.

[27] Toronto, Forever and Ever, 65–66.

[28] Toronto, journal, September 16, 1929, 268.

[29] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 50.

[30] Toronto, journal, December 27, 1929, 370.

[31] Toronto, journal, February 7, 1930, 46.

[32] Toronto, journal, February 29, 1930, 68.

[33] Toronto, journal, September 26, 1930, 278.

[34] Toronto, journal, February 25, 1931, 64.

[35] Toronto, “Some Socio-psychological Aspects,” 6–7.

[36] Toronto, Forever and Ever, 72.