"How Long Can Peace Last?"

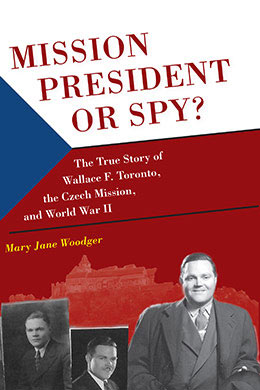

Mary Jane Woodger, "'How Long Can Peace Last?'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 81–90.

Omens of war had reared their heads for years in Czechoslovakia. As early as January 30, 1933, when Hitler was pronounced chancellor of Germany, missionary Spencer Taggart reported that “no one cared to listen” to his gospel message. Instead, everyone wanted to talk about Hitler, and everyone seemed to be “extremely apprehensive of how this [might] affect Czechoslovakia.”[1] In June 1936, right after Wally once again stepped on Czechoslovakian soil, he witnessed a precursor to war himself when he visited the Aerial Exposition of the Republic held in the Stromovka. There he “saw scores of planes and war machines, and the development of all kinds of ariel defense technique.” He watched people test their parachutes. There were huge searchlights and antiaircraft guns. Wally considered that Hitler must have “thousands upon thousands” of such armaments, as might Mussolini.[2] Russia was also building its air preparations. In July 1936, Wally recorded, “Oh, the fools that men are! How many other secret preparations are going on, quietly and unnoticed? The man in the ranks will never know. Such an experience makes one believe that a conflict is inevitable. When it will come one cannot know, but each nation is secretly preparing to plunge itself—the flower of its young manhood—into war and bloodshed. To ride through miles of country plunged into darkness and to hear the planes roaring overhead, chilled our blood when we reflected on its meaning.”[3]

In fact, according to Wally, all of Europe was “[shuddering] to think of the havoc of the next cataclysm.”[4] Wally wondered, “How long can peace last, with all of this material manufactured for no good purpose? If all the money and investments in such war machines could only be put into public education, medical research, social programs for assisting the unemployed—oh what a world we would live in. But the Devil can’t seem to see it that way.”[5] By November of 1937, he noticed that the tension in Europe seemed “to sway from week to week.” He noted that Hermann Goering “announced that Germany [could] no longer honor the terms of the Versailles Treaty. This . . . caused much uneasy comment.”[6]

Wally knew that changes were on their way to Czechoslovakia, and such knowledge only increased his missionary efforts. However, the impending war and the climate of conflict did adversely affect him and his missionaries in countless ways. When he and his missionaries were denied three times in four months the right to hold meetings, he realized that restrictions were tightening up. “This can be readily understood when one considers the strained relationship of the Czechs with the German minority here, and the recent unpleasant experiences with spies and foreigners, principally Germans. Thus I believe that we have been denied, not maliciously, but generally with all others. Therefore we must secure a decision in our favor through the necessary government offices.”[7]

Along with everyone else in Czechoslovakia, Wally watched as Hitler reached out to various countries. In his journal, he noted the event when Mr. Schuschnigg of Austria[8] met with Hitler and had “an official meeting to bring Austria into closer contact with Germany.”[9] Even an alliance with a remote country like Austria caused considerable concern in Czechoslovakia. Wally reflected on the worsening state of Europe. “Any concessions granted mean a strengthening of the Berlin-Rome axis, which democratic and free countries are wont to accept or permit. It also seems that England is having some difficulty with her cabinet and that a new foreign minister may be named in place of Eden.[10] One cannot keep pace with the changes.”[11]

On the last day of 1937, Wally wrote of his devotion despite the increasing tension: “Although war and trouble seem to threaten Europe, yet our confidence is such that we and our members shall be blessed in the carrying out of our responsibilities, come what may. We have only one objective for the coming year, and that is to preach and teach the Master’s Gospel of love and peace, as never before. And it is so needed in the world today. May the Lord bless us to accomplish that aim during the coming year.”[12] At the same time, Wally was well aware that things were not going to get better. In February he admitted, “It seems according to prophecy, that we cannot look forward to good times in the immediate future. The earth is virtually in tumult now.” The newspapers became “alive with comments” about Austria’s breakdown and loss of independence “brought about by a long chain of events . . . culminating in the conference of Schuschnigg of Austria and Hitler of Germany, in which the latter succeeded in binding Austria more firmly to the Nazi program.”[13]

Following the Anschluss, or union, of Nazi Germany and Austria in March 1938, it seemed clear to Wally—and everyone else—that the conquest of Czechoslovakia was Hitler’s next ambition. The incorporation of the Sudetenland (the borderland areas around Czechoslovakia) into Nazi Germany would leave the rest of the Czech nation weak and powerless to resist subsequent Nazi occupation. Czechoslovakia would surely be the next objective of the Nazi regime because of its four million German minority. Wally recorded, “Hitler has declared and is using every means to bring his dream true, that all German peoples shall be united under his leadership. But this nation of Czechoslovakia stands invincible, cultivating closer relationships with Great Britain and France.”[14] On March 16, 1939, the German Wehrmacht did move into the remainder of Czechoslovakia, at the Prague Castle, and Hitler proclaimed occupation.

With the union of Austria and Germany, tension in Prague began to surface. Wally could almost “feel it among the people.” The Czech cabinet was called together and remained in session all night, “considering the events as they transpired in Vienna. And events moved fast.” When Kurt von Schuschnigg, chancellor of the First Austrian Republic, was forced to turn the government over to Nazi leaders, “Austrian flags were torn down, the German Svastika was displayed, and the Austrian Legions made up of exiled Austrian Nazis who had found temporary shelter in Germany, began to march on Austria. . . . Several of the former cabinet members . . . fled to . . . Czechoslovakia.” Wally observed, “It looks as though Austria has definitely become a permanent part of Germany. The newly formed government has requested the German government to send in soldiers to quell any revolutionary movements or uprisings.” Then Wally predicted, “The next few days may tell a story of blood-shed and murder. At least they will be days of high tension for Czechoslovakia.”[15]

Soon after the birth of another Toronto child, Carol, things began to escalate very quickly. On May 21, Wally learned that two Germans who had attempted to cross the Czech frontier near Eger were “shot down by the border police, when they refused to stop upon command.” When German troops moved toward the border, it seemed to Wally that “Hitler would seize the country. But the Czechs moved to the border as well, with a well-trained army prepared to fight to a finish.” While war began raging in Czechoslovakia, British ministers deliberated restlessly through the night. They finally concluded that “they would follow France into any European struggle.” France was bound by a treaty “to preserve the freedom and democracy of Czechoslovakia. Thus Hitler was stopped.”[16]

In early May 1938, Wally went across the Czech border to the mission home in Berlin where he met with mission president Alfred C. Rees. On his journey to Bodenbach, a German municipality located near the border, Wally saw both the Czech and German flags waving side by side. At the border, he realized that things had changed dramatically as the guards made a more careful inspection than ever before.

All cushions of the car we were in were removed and all door and window frames were tapped in an effort to detect hidden stores of German propaganda. . . . We also saw soldiers all along the railroad track and at every bridge, with their guns and bayonets ready for action if necessary. In the town great signs were on the buildings: “We will never surrender our rights,” and, “We will persevere to the end!” The Czechs evidently are willing to give all they have—life if required—to protect their freedom and rights from German invasion. One cannot help but admire their fortitude and courage.[17]

In June 1938, Wally met with a group of other mission presidents to talk about the situation in central Europe and how it was affecting their various missions. In attendance were J. Reuben Clark of the First Presidency; Thomas E. McKay, president of the Swiss-Austrian Mission; Franklin J. Murdock, president of the Netherlands Mission; Alfred C. Rees, president of the East German Mission; and M. Douglas Wood, president of the West German Mission. President Clark felt significantly concerned about the work in Germany and wondered how long the missionaries could hold out under the stifling methods being used by the government. He was very “pessimistic about it, after talking about the religious situation in Germany with some of the officials who quite openly declared that they had little use for religious activity.” He also felt that Czechoslovakia was in great danger; he suggested that Wally “take every precaution and without upsetting [his] missionaries plan routes of escape.”[18] President Clark suggested to the mission presidents that they “come together about once every two months to size up the situation politically as it relates to our missionary work, and to encourage one another. It was tentatively decided that [they] should meet in Basel sometime in August, since Berlin or Prague were unsafe for the discussion of such matters.” When the mission presidents said goodbye to President Clark, they felt that their “gathering had been most profitable, although none too encouraging for the future of [their] work in Central Europe.”[19] Wally wrote in his journal, “‘To what good purpose can it all come?’ It is for defense of course. But it means that the dread of war hangs over the central European countries, and it means more than that—it means that war is sure to come, sooner or later. Oh how the people of the world need the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the peace and happiness it brings. But they seem to have no time for it. Yes, the devil is at work, and oh so subtly.”[20]

In July 1938, Wally gathered his missionaries in Prague for a conference. Unbeknownst to them, it would be the last conference they would hold for a decade. “Between conference sessions, they attended the demonstrations of the tenth Sokol Slet, celebrating national unity and being ‘one with the people.’” The Sokol Slet was an international gymnastics festival held every six years. But, as Kahlile Mehr said, “It was a unity that could not be sustained in the face of brute German force.”[21]

In August, Wally went to the U.S. legation to “talk with Mr. Chapin about means of evacuating, in case of war.” Although things had settled down briefly, he felt things would soon become dangerous again. The Germans were making great strides in their military preparation and holding maneuvers, which Wally thought was their attempt “to frighten Czechoslovakia into accepting the terms of the Henlein party.” As Wally put it, “The problem is not one between the Czechs and the Sudete Germans but between the Czechs and Berlin, or Hitler. Thus anxiety is again in the air.”[22] Chapin explained to Wally some of the issues:

The U.S. Legation had been giving some thought to the problem of possible means of escape, but that plans made out ahead of time in such cases could not often be relied upon. He felt that the wise thing to do would be to have all of the [missionaries] in Bohemia gather at Prague, where the government might be able to arrange to remove all Americans. For the [missionaries] in Moravia [Chapin] suggested that they go east through Slovakia to Romania and then attempt to get to Switzerland from there. He felt that Hungary and Poland could be considered as potential enemies of Czechoslovakia, and that escape through those countries could not be counted on. He further stated that as soon as the Minister came from his vacation that they would consider this matter still in more detail and let [Wally] know.[23]

Wally confessed, “I have no particular fears, but thought it well to have something in mind—be prepared, if such a thing be possible during international catastrophe. What I should like to do is send the brethren some instructions as to what to do in case war is declared or open hostilities arise.”[24]

In September, the Czech government was forced to make a stand and “declared martial law in eleven of the border provinces in order to preserve order. Following this peace and quiet seemed to ensue.”[25] Wally had a sense of how his people were coping, what they were feeling. But, sadly, he could do nothing. In September of 1938, “Hitler demanded the Sudetenland in western Czechoslovakia, where a substantial minority of Germans lived. Soon afterward, the First Presidency ordered the missionaries and the Torontos to leave immediately for Switzerland. Concurrently, the Czech government banned all public meetings. The mission temporarily ceased to function.”[26]

Wally immediately sent Martha with four-year-old Marion and twenty-month-old Bob to Switzerland, where they could stay in the mission home in Basel with the McKays. Later, Wally and all the other missionaries followed. The children and Martha would “remain in Switzerland for three months.” Wally then “sent the older missionaries home and the others to England to work temporarily in a mission where they could use their native tongue.”[27] At the time of the evacuation, twenty-three missionaries were working in eight Czechoslovakian cities and towns. From the missionaries’ standpoint, the year was successful because the membership in organized branches stood above the previous year’s average, and many people had heard the gospel message.[28]

Wally wrote to the missionaries’ parents to let them know about the situation. In one such letter, he wrote:

Prague, Czechoslovakia

September 19, 1938

Dear Parents:

I am happy to inform you at this time that your son, who has labored so splendidly among these people and who despite the trying political conditions in Central Europe has maintained his morale, fine spirit and enthusiasm, is now safe and sound in Basel, Switzerland.

Upon the advice of the First Presidency this move was made, since it was felt that conditions in this country were too precarious to permit further missionary work at the present time. Thus, the last group of missionaries left Prague on Saturday, September 17th. I have since been advised by President Thomas E. McKay of the Swiss-German Mission that all arrived safe and sound and are comfortably taken care of. The missionaries shall remain under his direction until I, myself, am able to join them.

I suggest that until further notice you address all mail to your son to the following address:

Swiss-German Mission

Leimenstrasse 49

Basel, Switzerland

We are very hopeful that negotiations in the near future will tend to clear up the present nervous tension in Central Europe, and that we shall all be able to return and carry on our work as formerly. However, in the meantime our group of missionaries will carry on in Switzerland, and thus continue to be a credit to you and to the Church.

You may well be proud of the conduct of your son during these trying times, for he has persevered despite many difficulties. We thank the Lord that you have been able to give us such a fine, capable representative.

May the Lord continue to bless you in your undertakings and give you the assurance that your son is safe, well and happy in his work. Praying the choicest blessings of heaven upon, I remain

Cordially your brother,

Wallace F. Toronto

Mission President[29]

When all the missionaries had been reassigned, Wally joined Martha and the children in Basel, resigned to accept the inevitable events of the future, come what may.

Notes

[1] Spencer Taggart, “Becoming a Missionary, 1931–1934,” typescript, 1989, 31.

[2] Toronto, journal, June 13–19, 1937, 115–16.

[3] Toronto, journal, July 5–11, 1936, 14.

[4] Toronto, journal, June 13–19, 1937, 116.

[5] Toronto, journal, June 13–19, 1937, 115–16.

[6] Toronto, journal, November 7–13, 1937, 161; Hermann Goering was a powerful military figure during Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany leading up to and during World War II.

[7] Toronto, journal, December 12–18, 1937, 175.

[8] Kurt von Schuschnigg was the chancellor of Austria and did not want Hitler to take control of Austria.

[9] Toronto, journal, December 12–18, 1937, 198.

[10] Sir Robert Anthony Eden served as Britain’s secretary of state for foreign affairs from 1935 to 1955 intermittently (due to war and health) until he succeeded Winston Churchill as prime minister (1955). Sir Eden replaced Sir Samuel Hoare as foreign secretary in 1935 and was replaced by Edward Frederick Lindley Wood (Lord Halifax) in 1938 and by Harold Macmillan in 1955.

[11] Toronto, journal, February 6–19, 1938, 198.

[12] Toronto, journal, December 26–31, 1937, 180.

[13] Toronto, journal, February 27–March 5, 1938, 202–3.

[14] Toronto, journal, February 27–March 5, 1938, 203.

[15] Toronto, journal, March 6–12, 1938, 205.

[16] Toronto, journal, May 15–21, 1938, 228.

[17] Toronto, journal, May 22–25, 1938, 231.

[18] Toronto, journal, June 12–18, 1938, 236.

[19] Toronto, journal, June 19–25, 1938, 238.

[20] Toronto, journal, July 3–9, 1938, 243.

[21] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 69.

[22] Toronto, journal, August 7–13, 1938, 253.

[23] Toronto, journal, August 7–13, 1938, 253–4.

[24] Toronto, journal, August 7–13, 1938, 253–54.

[25] Toronto, journal, September 11–17, 1938, 263.

[26] Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 69; and Czechoslovak Mission Manuscript History, December 20, 1938; June 20, 1939.

[27] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 17.

[28] Toronto, journal, December 25–31, 1938, 309.

[29] Toronto, journal, September 11–17, 1938, 264.