"He Should Stand at the Head of His Race"

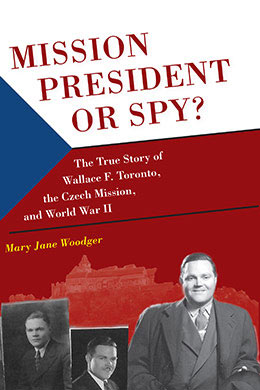

Mary Jane Woodger, "'He Should Stand at the Head of His Race,'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 1–10.

Nothing in the birth of Wallace “Wally” F. Toronto in Salt Lake City on December 9, 1907, suggested he would have any connection with Czechoslovakia nor achieve any greatness. His birth was a normal one in the obscurity of the Rocky Mountains. The only inkling that he would become great, and had a destiny to fulfill, came from two generations earlier because of his grandfather Giuseppe Efisio Taranto.

Giuseppe Taranto, the son of Francesco Taranto and Angela Fazio, was born on June 25, 1816, in Cagliari on the island of Sardinia. Sometime in his early twenties, he joined the Mediterranean Merchant Service, which was a commercial shipping company that often took him to foreign ports around the world. At one point, he found himself in New Orleans and decided to stay and work there for a while on American ships. He frequently sailed to other states on the coast such as Massachusetts and New York.[1] He worked hard and saved his money, rather than spend it “on wine and women,” as other sailors did, so he could send it back to his family in Italy.[2] During one journey to New York City, he began to fear that someone might steal his money once he got there.[3]

That night, he had a dream where a man approached him and told him to give his money to “Mormon Brigham.” And told him that if he did so, he would be blessed for it. Once the ship anchored at the harbor, Giuseppe went to work finding “Mormon Brigham,” but nobody he asked seemed to know anything about him.[4] Though he went on with his life the same as usual, the dream would stay with him, and prepare Giuseppe and later his grandson’s participation in not only a religion but an entire way of life.

From New York, Giuseppe went to Boston, where he started working for an Italian shipping firm, earning enough to purchase a small boat of his own and start his own business. “He made a living by buying fruits and vegetables from the wholesale vendors in Boston and then selling them to the large ships at anchor in the harbor.”[5]

In Boston, Giuseppe first learned of some Mormon missionaries preaching about “the gospel as restored through Joseph Smith only a few years before.” When Giuseppe heard the truth, he embraced it, and in 1843, at the age of twenty-seven, he was baptized by Elder George B. Wallace, becoming “the first native Italian and also the first Roman Catholic to join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” The missionaries counseled him to join with the Saints in Nauvoo as soon as possible. But he was doing so well financially that he decided instead to continue increasing his profits to send back to his “poverty-stricken family in Sicily.”

Giuseppe remained in Boston for about another year and a half, coping with the new language and culture. In an effort to fit in a little more, he anglicized his name to Joseph Toronto. The spelling change in his surname resulted from his illiteracy. Like most Sicilians of his age (or any foreigner for that matter), he could not read or write his natural dialect and had someone else write his name down for him, spelling it the way it sounded in English. Hence, the new name stuck for the following generations.

One irony of Joseph’s life was that though he was a highly skilled seaman and had spent most of his life in ships on the water, he did not know how to swim. He might have stayed in Boston for much longer had he not experienced a nearly fatal accident in the spring of 1845. One day, while transporting a load of fruits and vegetables in the Boston Harbor, his boat collided with a larger ship and capsized. He lost most of his cargo and almost his life from drowning. The event marked a traumatic and terrifying turning point in his life, for because of the accident he decided to heed the counsel of the elders and go to Nauvoo, Illinois. Subsequently, he sold his small vessel and his business and headed west.

By the time Joseph Toronto immigrated to Nauvoo, the capstone of the Nauvoo Temple had just been put into place. As work inside the temple progressed, persecution and the Saints’ lack of financial means to provide food and clothing for the workmen slowed the work. Some men working on the temple were even barefoot and shirtless. “When the situation became critical, President Brigham Young instructed those in charge of the temple funds to deal out all the remaining provisions with the promise that the Lord would give them more.”[6] On Sunday, July 6, 1845, he announced that the “work on the temple would have to cease.” The tithing funds were depleted. Even though he had appealed to Saints who were traveling from overseas to sacrifice some of their money “to finish the Lord’s house,” their contributions had not produced as much as the prophet had hoped for. “Work on the temple would have to stop, with the Mormons endangering their salvation thereby”[7] (see D&C 124:31–33).

Joseph Toronto, who was present in the congregation, was deeply moved by the words of the prophet and “determined to do whatever he could to help move the work along.” The very next afternoon, President Young met with him in his office and recorded in his diary the events that transpired. “Brother Joseph Toronto handed to me $2,500 in gold and said he wanted to give himself and all he had to the upbuilding of the church and kingdom of God; he said he should henceforth look to me for protection and counsel. I laid the money at the feet of the bishops.”[8] William Clayton recorded that $2,599.75 was the exact sum that Joseph gave to the Church—all in gold that was wrapped in old rags and tin boxes.[9] As Joseph donated his hard-earned life savings to the temple, Brigham Young blessed him that “he should stand at the head of his race and that neither he nor his family should ever want for bread.”[10] That promise would extend through the next two generations, eventually even down to Wallace Toronto, his grandson.

When Joseph had first arrived in Nauvoo, some Saints were prejudiced against him because he was the only Italian they had ever met. His olive skin, jet-black hair, and dark eyes yielded condescending remarks from a vast number of Saints, who were predominately Northern European. Joseph never exhibited any knowledge that he was not accepted. Instead, he would flash a genuine smile to everyone he met. “He was [as] friendly as a puppy dog. He loved to bear his testimony . . . and didn’t seem to notice that as the spirit came upon him and he became emotional about the gospel, his accent became thicker and thicker, until the Saints ducked their heads with tongue in cheek to repress smiles.” Those feelings of bias, however, dispelled completely when the Saints witnessed Joseph’s act of financial generosity and sacrifice. One Latter-day Saint in particular, Dr. John M. Bernhisel, had been deeply prejudiced against the young Italian convert. But he was present at Joseph’s meeting with President Young and watched “as Joseph fumbled under his shirt [to draw] forth [his] money belt.” As he opened it and spilled the gold on the table, immediately “Bernhisel felt sheepish at his superior attitude toward a man because of his olive complexion and strange accent.”[11]

After Joseph’s donation, a strong relationship grew between him and the prophet. Joseph “became a permanent member of the [Young] family.” And, once he arrived in Salt Lake City, he began working for President Young.[12] However, this employment was short-lived when on April 29, 1849, President Young informed Joseph of his desire to send him “to his native country . . . to start the work of gathering from the nation.” During general conference that next October, President Heber C. Kimball called Lorenzo Snow and Joseph Toronto to serve a mission in Italy. On this mission, Joseph was able to visit his home in Palermo and share the gospel with his family. By the time he returned to Salt Lake City in August 1851, he had even baptized several members of his own family.[13]

The prophet continued to provide for Joseph once he got back to Utah and was even instrumental in finding him a wife. As Joseph was beginning to establish a homestead, President Young called him into his office one day and announced, “There is a nice Welsh convert named Eleanor Jones, and I think that you should marry her.” Following the prophet’s counsel as always, Joseph married Eleanor in the fall of 1853, and Zina D. Young provided a beautiful reception for them at the Lion House.[14]

After almost twenty years of marriage, the Torontos hired a young Swedish convert named “Anna Catharina Johansson to live with them and help care for the family.” When Eleanor and Anna became very close, Eleanor suggested that Joseph take Anna as a second wife because she had no family of her own to support her. “Reluctantly, and only after much persuasion from Eleanor” and an endorsement from the prophet, Joseph finally agreed. On January 22, 1872, he took Anna’s hand in marriage at the Endowment House. At the time, he was fifty-six years old, and she was thirty. From that union would come Albert Toronto, the father of Wallace F. Toronto. Albert was born on February 4, 1878, in Salt Lake City. Just five years later, Joseph Toronto would pass away.[15]

Albert Toronto

As a young adult, Albert Toronto attended the University of Deseret, graduating with a major in business. Following his father’s example, he served a mission in Germany from 1899 to 1902. Early in his mission, he experienced the blessing of the gift of tongues. He had barely arrived in his mission area, having not yet learned German, when he and his companion began tracting. For some reason, his companion had to leave him for a moment. While his companion was gone, Albert struck up a discussion with a German stranger. Albert was amazed to see that the stranger understood what he was saying, and he understood the man’s German just as well. As the two conversed, Albert began to teach him about the gospel. When his companion returned, he suddenly found that he could no longer speak or understand German. The companion then continued teaching the man where Albert had left off. This man eventually joined the Church. Thereafter, Albert picked up the German language quickly.[16] Joseph’s propensity for languages would be passed down to his son also.

When Albert returned from his mission, he found employment at Barton’s Clothing Store in Salt Lake City as a cashier. Through his experiences there, he learned how to maintain a neat and attractive appearance, which was especially beneficial to his social life. In 1902 he attended a party with his sister. The siblings did not stay very long, but they made sure that they met everyone there before they left—including one Etta Felt. When Etta returned home from the party that night, she told her mother that she had found a young man she wanted to marry someday, “if he would have her. ‘I’ve never heard you say anything like that before,’ her Mother said. ‘I’ve never met anyone like him before,’ Etta answered.”[17]

Etta Felt

Etta was born in Salt Lake City on February 21, 1883, to Joseph Henry and Alma Elizabeth Mineer Felt. Her schooling started when she was eight years old. Just five years later, when she was only thirteen, she graduated from the eighth grade. Most of her classmates “claimed she was the teacher’s pet,” but she declared that she had received her “class promotions” because she worked so hard. After graduation, she went to work at a cracker factory, receiving $3.50 a week. At age fourteen, she got a job at a telephone company, gaining a small improvement in wages: fifteen dollars a month. At the time, the minimum age to be hired by the phone company was fifteen, and Etta was a bit too young. Nevertheless, the chief operator liked her and decided to test her to see if she could do the job. One of the tests required that the applicant’s arms be “long enough to reach to the outer edges of the switch board.” Luckily, Etta’s arms passed the test. She was also fairly tall and looked older than her age. As such, the operator said, “Maybe if you put your hair on top of your head like the older girls and lengthen your skirts, you can pass for 15.” She did as she was instructed and was hired.[18]

In 1903, Etta was called to serve on her stake Sunday School board. When she attended her first board meeting, who should appear but the young man she had met at the party two years earlier, Albert Toronto. After the board meeting ended, Albert asked her if he could walk Etta home, and from that time forward, the two were inseparable. John R. Winder officiated their marriage on June 14, 1905. The couple then moved to Portland, Oregon, where Albert sold insurance and Etta worked in the Utah booth at the World’s Fair. After three months of an extended honeymoon in Oregon, they returned to Salt Lake City and moved in with Albert’s mother in the Toronto home on A Street. It was not uncommon at that time for newlyweds to live with their parents because it was an “old country” tradition.[19]

Karlstejn, dedication site for Czechoslovakia, July 24, 1929. Courtesy of Mary Jane Woodger.

Karlstejn, dedication site for Czechoslovakia, July 24, 1929. Courtesy of Mary Jane Woodger.

For many years, Etta cotaught an institute class with another teacher, Lowell Bennion. The University Ward had many students attending and there would sometimes be as many as forty or fifty students in the class. For Etta, it felt like a great challenge to provide the students with lessons that would benefit them. She must have succeeded for years later, many of her former students returned to tell her of the good influence she had been in their lives.[20]

While Etta devoted much of her time to teaching institute, her husband worked to support his family. At one time, “[Albert] bought into National House Cleaning, a janitorial business for cleaning homes; but it proved too much for both him and Etta, so he gave it up.” Afterward, they ended up moving in with Etta’s mother in her small home on Seventh East, where Etta assisted her mother in sewing burial clothes. Albert was able to help support Etta’s brothers, Joe and Lamont, on their missions. Albert and Etta never wanted for food and were always able to support themselves.[21]

When Brigham Young prophesied that Joseph Toronto “should stand at the head of his race and that neither he nor his family should ever want for bread,” that promise seemed to extend to his son and then his grandson Wally, as well as the promise that he would never want for anything to eat, and, more importantly, he would stand at the head of another race: the Czechoslovakian Latter-day Saints.[22]

Notes

[1] James A. Toronto, “Giuseppe Efisio Taranto: Odyssey from Sicily to Salt Lake City,” in Pioneers in Every Land, ed. Bruce A. Van Orden, D. Brent Smith, and Everett Smith Jr. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 126–27.

[2] Samuel W. Taylor, Nightfall at Nauvoo (New York City: Avon Books, 1971), 356.

[3] Toronto, “Giuseppe Efisio Taranto,” 127.

[4] John R. Young, Memoirs of John R. Young (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1920), 47.

[5] Toronto, “Giuseppe Efisio Taranto,” 127; see also Alan F. Toronto, Maria T. Moody, and James A. Toronto, comps., Joseph Toronto (Giuseppe Efisio Taranto) (Salt Lake City: Toronto Family Organization, 1983), 7.

[6] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Joseph Toronto, 8.

[7] Taylor, Nightfall at Nauvoo, 356.

[8] Toronto, “Giuseppe Efisio Taranto,” 129.

[9] William Clayton, “Nauvoo Diaries and Personal Writings,” Nauvoo, July 8, 1945, http://

[10] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Joseph Toronto, 8.

[11] Taylor, Nightfall at Nauvoo, 356.

[12] John Young, Memoirs of John R. Young, 47; and James Toronto, “Joseph Toronto” Pioneer 62, no. 1 (2014): 15.

[13] Toronto, “Joseph Toronto,” 15–16.

[14] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Joseph Toronto, 16.

[15] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Joseph Toronto, 17.

[16] Joseph Y. Toronto, Maria T. Moody, James A. Toronto, comps., The Story of Albert and Etta Toronto (Albert Toronto Family Organization, February 21, 1983), 1, 5.

[17] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 1, 15.

[18] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 14, 68.

[19] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 15, 32.

[20] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 16.

[21] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Story of Albert and Etta Toronto, 2.

[22] Toronto, Moody, and Toronto, Joseph Toronto, 8.