"Communism Espouses Religious Freedom!"

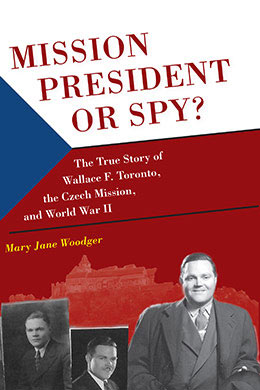

Mary Jane Woodger, "'Communism Espouses Religious Freedom!'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 209–216.

Wally and Martha experienced great success in seeing most of the Czech Saints during their fifteen-day stay, and they felt they had accomplished what the Lord desired of them. But Wally could not shake the feeling that he needed to go back one more time. After a few months, he once again went to President McKay to ask his advice on taking another trip to Czechoslovakia. Wally informed the prophet that he did not want to see the members on another visit but rather that he wanted to see government authorities, especially those in high offices of the ministries over religion and education. “He was sure he could talk them into letting him re-establish the mission and get permission for public meetings again. He already knew some of these men in high places because he had visited them in Washington D.C. when they were in the Czech Embassy there. He felt this was a way to open the door.”[1]

An opportunity did open up for Wally. Every ten years, Czechoslovakia held a large athletic festival and exhibition called the “Sokol Slet.” Of course, the Communists had given it a Russian name instead: Spartakiad.[2] The events were being held in Prague in 1965. Wally, then, found a perfect excuse to obtain a visa. All nations were invited to attend, making it easier to get one. President McKay agreed to send Wally in an official capacity for his next visit. He also advised him that he should go by himself. Though Wally was discouraged about leaving Martha home alone, he later recognized that it was “a fortunate inspiration on behalf of . . . President [McKay].”[3]

Wally arrived in Prague as planned in July 1965, during the celebration of the Sokol Slet. “As [he] was sitting there in a crowd of 25,000 people, a cameraman spotted him as an American and asked him to stand in front of the camera and tell the nation about his impressions of the ‘Spartakiada.’”[4] In a blessing he had received years before, he had been told that he would testify to the nation. At that moment on camera at the Sokol Slet, it seemed that the prophecy was beginning to be fulfilled. But Wally had hoped he would manage getting in and out of the country without any fanfare or attention. His television appearance ruined his plans. Afterward, surely everybody would know he was in Czechoslovakia.[5]

In fact, on that very day, Gad Vojkůvka’s mother sent Gad to go shopping. For some reason that not even he could recall, he decided to turn on the television set in the living room before he left. The TV started making a high-pitched noise. Gad returned to the room to check what was wrong. Much to his surprise, he saw the face of his much-loved mission president on the screen. Gad was in shock. He immediately called to his family to join him in the living room to watch as Wally nonchalantly talked about his children and where he lived.[6]

The following morning, Wally started visiting people at the various offices of the ministries. Many officials recognized him as the man they had seen on television the day before. Naturally, like Gad, some other Church members had also seen him, so they traveled to Prague to visit him, which was exactly what he had wanted to avoid. He feared that any visits from the Saints could jeopardize his mission to speak with the officials of the government. Despite the notoriety, he seemed to make some progress in his discussions with the officials that he had gone to see. Wally was able to speak to officials in the Ministry of Archives regarding the genealogy and microfilm proposal, and he received word that they were still interested in that project. He also visited the Ministry of Health and Welfare and was welcomed with a “a regular spread . . . [of] Lindon tea and all kinds of sandwiches,” a reception Wally had never received during official business. The doctors there who had received Wally’s magazines and other materials about cancer had accepted Wally as someone who could truly benefit their nation, medically speaking.[7] Overall, he was treated well and believed he was on his way to getting permission “to get the mission ‘above ground’ and recognized by the Communist regime.”[8]

Wally’s most important interview was to be with the Minister of Religious Affairs. He was scheduled to be at the Ministry of Interior on July 12. Because securing a meeting with the man was so difficult, the appointment was a little tentative. On July 8, he and Brother Kubiska, the acting mission president, “drove out into the country about 200 kilometers away from Prague” where Brother Kubiska’s sister lived in a farmhouse.[9] While Wally was relaxing, two men came to the door, identified themselves as secret police from Prague, and demanded that Wally go back with them to Prague. Bob Toronto remembered his dad describing his experience. It was the only time Bob ever recalled his father saying anything about being afraid. He asked what they wanted with him. They answered, “We can’t tell you that. That will be told you back in Prague.”[10] Wally soon discovered two more men outside: one to drive his car back, and one to drive the secret police’s car. During the car ride, Wally tried to engage in conversation with them over and over, but they gave him nothing.[11]

Once they arrived in Prague, they immediately took Wally to a government building. To his good fortune, that building was where all the ministers were located, including those with whom he had been trying to procure an audience. Previously, he had been denied access to the Ministry of Religion. They would not even give him an audience then. The officials began their questioning. “During the interrogation he was accused of such subversive activities as stirring up the people and inciting them against the regime, trying to establish the Church illegally again in Czechoslovakia, and bringing in missionaries.”[12] Denying all these charges, he told them he was actually there to visit the ministries.

With newfound courage, he talked to them about his earlier trip with Martha. He explained that he had told Church members at that time that he could not do anything to help them with open worship. Wally “took occasion to tell them of the splendid work the Mormon Church had done in Czechoslovakia,” work that ranged from humanitarian relief efforts in post-war years to saving villages that had been flooded out. He also took the opportunity to bear “testimony to them of the truthfulness of the gospel, of the need for it, [and that it would] bring lasting peace, harmony, and happiness to the world.”[13] The interrogator told Wally that they knew about his visit in January and about everything he and Martha had done.[14] And with even greater courage, Wally charged back at their harsh questioning, “Why are you afraid of 500 Mormons? Why are you afraid of that? Why did you pick me up?” He was surprised when he realized he was not afraid of his interrogators anymore.[15]

What could have been a terrifying experience turned into a blessing. One of Wally’s interrogators was the very man he had hoped to meet on July 12. The man was, after all, in charge of all things religious in the country. Therefore, it was only natural for him to be called in on Wally’s case. The smug Communist official informed Wally that seventeen other churches had already been granted state recognition, and in anger he slammed his fist on the table to prove his point. “Communism espouses religious freedom!” he claimed. Wally responded, “You proclaim that you have religious freedom here? What about the many people that don’t belong to these seventeen churches? Where’s your freedom?” Stunned by Wally’s argument, the minister warmed up a little bit and said, “Maybe you could come back again and we can culminate our talks about this matter in a more friendly atmosphere.” Wally responded resolutely, “I want to put down notice that I will be back. The Mormon Church has not forgotten the people over here in Czechoslovakia.”[16]

The questioning was rough and severe, but Wally kept his composure and resisted showing any visual fear or anger, which confused and bothered the officials. He believed that the Lord had given him “the strength and the wisdom he needed to say the things that had to be said.” He recited the history of the mission, a mission that he had personally been a part of since its inception in 1929, ending with his expulsion from Czechoslovakia in 1950. He explained his desire that Church members be left alone and allowed at least the privilege of meeting in groups under the direction of local men. The officials told him that they already knew who the local leaders were, a fact that did not surprise him at all.[17] Before ending the conversation, one of the officials said to him, “When the hammer and sickle are emblazoned across all of America, then you will know that the Communist way is the right way.”[18]

Wally was again unable to change anything for Czech Latter-day Saints that day. Unfortunately, “mission growth would be suppressed for another twenty-five years before reemerging in a new epoch of freedom.”[19] Nevertheless, Wally informed the Ministry of Interior to take notice that he would keep trying to accomplish his purpose later. Even though he was detained as a prisoner, he believed that his visit to “the highest ministry in the land” was successful. After all, had he not been arrested, “he never would have been able to see all [of the] important government officials, and especially all at the same time.”[20] But at the conclusion of the interrogation, Wally was told that his presence in Czechoslovakia would no longer be tolerated and that he was to leave the country that night. The secret police would accompany him to the German border. He insisted that he had a plane ticket to Vienna for the next day and asked if he could stay the night. The answer was “absolutely not.” They would take him to the border that very night.[21]

The same guards who picked him up in Brno put him in the same car and drove him and his luggage three hours to the Czech border. Wally had no plans to go through Germany, but he also had no choice. “This is as far as we go,” the guard said as he dropped Wally off. Wally picked up his bags and walked half a mile to the West German border station. When he arrived at the station, the German guard looked him over suspiciously. After all, it was not common for a man to appear at his station at one o’clock in the morning, especially without a vehicle. Fortunately for Wally, he could speak German almost as well as he could English. He satisfied the guard’s reservations and explained his situation.[22] The two engaged in a gospel conversation, a merciful ending to an unsatisfying journey. Wally remembered, “There I was with this lonely border guard on the German side, but I preached the gospel to him.”[23] The next day a taxi picked up Wally and took him to a train station.[24]

As devoted and dedicated as he was to restoring the legality of Church worship, Wally did not have the blessing of returning to Czechoslovakia after his last visit in 1965. He had always planned to go back later and accomplish his purpose, just as he had told the Ministry of Interior. He would have done anything to get the Church above ground again.[25] Unfortunately, it would not be in his lifetime that his plans for Czechoslovakia, the nation he cherished so much, would come to light.

Notes

[1] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 100.

[2] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 8.

[3] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 100–101.

[4] Spartakiad or Spartakiade is the English spelling of the Czech word Spartakiáda.

[5] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 101–2.

[6] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013, 5.

[7] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 9.

[8] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 102.

[9] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 9.

[10] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 9.

[11] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 27.

[12] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 103–4.

[13] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 10.

[14] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 103–4.

[15] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 27.

[16] Toronto, fireside, 1965, 10–11.

[17] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 103–4.

[18] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 27.

[19] Mehr, “Czech Saints: A Brighter Day,” 51.

[20] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 103–4.

[21] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 27.

[22] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 105.

[23] Ed and Norma Morrell, interview, May 8, 2013, 7–8.

[24] Bob and David Toronto, interview, August 20, 2013, 27.

[25] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 106.