"Back to the Uncertainty of Czechoslovakia"

Mary Jane Woodger, "'Back to the Uncertainty of Czechoslovakia'" in Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 91–108.

The evacuation of Wally, Martha, their children, and the missionaries in August of 1938 was called by Church personnel a fire drill. Some Church members were critical of the way the 1938 evacuation took place, calling it a “false alarm rather than a fire drill.” But a year later, when Wally was required once again to evacuate, “some felt the exodus of the American elders might have failed if they had not benefited from the mistakes they made the year before.”[1]

Things began to calm down later that fall. While in Switzerland, Wally called local leaders in Czechoslovakia to take care of the branches until the missionaries were allowed to return. Jaroslav Kotulán in Brno and Josef Roubíček in Prague took charge during Wally’s absence. In September 1938, Adolf Hitler sent an ultimatum demanding that the Czech government surrender all of the Sudetenland. When the Czechs refused to comply, the Germans invaded the borderland areas anyway. Representatives of some of the soon-to-be Allied powers (France, England, and Italy) called a conference in Munich, demanding an immediate halt to Germany’s expansion or else they would face the possibility of war. Hitler signed an agreement, the Munich Diktat (Munich Pact), on September 29, 1938. He promised he had gone as far as he needed to go and would invade no further. Much to everyone’s surprise, Czechoslovakia believed him.

In early October, President Thomas E. McKay, who served as the supervisor over all the missions in Europe, urged Wally to send a telegram to the First Presidency suggesting that all of the former elders from Czechoslovakia be sent to England and that Martha and the kids return home. Wally complied, reluctantly writing the letter, though he still believed that he and Martha were supposed to go back to Czechoslovakia. Martha was pregnant at the time, and President McKay was very worried about her condition. He thought she would fare much better elsewhere. On the other hand, Wally felt that she would be fine giving birth again in Czechoslovakia, but he still sent the telegram to Church headquarters at the request of President McKay, who suggested that Martha either stay in Switzerland and seek medical care or go to London.[2]

Wally was right! In juxtaposition to what he said in the telegram, he would return to Czechoslovakia. After a month, many people believed that the crisis was over, and Wally’s mission secretary, Asael Moulton, was sent back to Prague to make sure it was safe for their return to Czechoslovakia. Wally arrived back in the country in mid-October. He sent a long report to the First Presidency, informing them that they were back in Prague and that conditions appeared to be quieting down. He hoped that Martha, the children, and the other missionaries would be able to return in the near future as well. He missed Martha immensely and hoped that by mid-November, she would be at his side again. He eagerly awaited her letters, devouring them once they arrived, and was very pleased when he read that all was well with her in Basel.[3]

On arriving back in Czechoslovakia, Wally checked up on the work that had gone on during his absence. He explored the possibility of holding meetings again, something that seemed to plague him regardless of the conditions of the country. He took an application to police headquarters for permission to conduct meetings for the Mutual Improvement Association and genealogical work. He visited Latter-day Saints, including Frieda Veněčková. She told him about how she had given up hope, after many vain attempts, that her atheistic husband would ever join the Church. She nevertheless kept the faith. She showed Wally the genealogical work that she had been able to do and gave him 270 crowns in tithes and fast offerings. “That is not a sign of faith wavering! Oh, if only some of our members in the branches where they have every opportunity to develop and grow in the Gospel, had but a particle of the faith of this beloved little Jewess, Frieda!”[4]

As Wally traversed around the mission, he found that the people were “depressed and shot-to-pieces mentally. They put on a bold cheerful front, but as we circulate among them, we feel and sense the depression of soul that grips all of them. Distrust, intrigue, betrayal, sold-out, are the terms running through their minds day after day. Perhaps the institution of the work camps will help stall this mania which is stirring within. At least, all is not yet well. They feel a crushing defeat at the hands of their ‘friends’—England and France.”[5] However, after seeing what had transpired with the Saints while he was in Switzerland, he was encouraged by what local leaders had accomplished.

During October and into November, Wally visited various branches, renewed the faith, and shared his testimony. On one trip to Taber, Wally was pleased to see forty people at a meeting, including some new faces. On that occasion, Wally felt that the Lord had blessed them with an abundance of the Spirit. “The Czech flowed freely” as he spoke from 1 Corinthians 13 “without the aid of paper.”[6] Wally instructed the people to keep reading the standard works and to live the gospel as they never had before.[7]

Wally acknowledged how much things had changed during his time away. Newspapers and radio shows were carefully censored so that “nothing must be done or said to offend Hitler and the Third Reich.” In just two months absence, the Czech government had made a “complete right-about-face in politics.” It was impossible and uncanny, he thought. He wrote in his journal, “A few weeks [before] it was democracy and freedom. Now it is Anti-Semeticism [Semitism], please Germany, scrape and bow to the whims of the Führer. But it has all been forced on them, subtly and cleverly, so that they do not detect the fact that they are betraying all that they formerly held sacred and just.”[8]

Wally also mourned that newspapers had begun “attacking both the Jews and the Czechs in a horribly vicious manner.” Czech Jews were doing anything they could to get out of the country.[9] By November, he had already received two telephone calls from Jews wishing to join the Church. Four other Jewish people had sent a letter to the Church offices in Salt Lake City, asking for an affidavit from the Church that would allow them to get to America and offer their services as doctors. In return, President Clark sent a letter to Wally and asked him to respond to their request, which he did. He “was instructed to get in touch with them and find out whether or not they were truly interested in the Gospel, as they had indicated, and to tell them that it was impossible for the church to supply such an affidavit.”[10]

Wally sent these Jews some Mormon literature and found out that they had been attending meetings in Brno. He then made an appointment with them to discuss the situation. He wrote, “They seemed to be fine people—clean, straight-forward and honest. The two wives were beautiful, lovely women, one a dentist and the other a teacher of languages.” Wally told them that he was not qualified to sign an affidavit but that he would try to find a friend who was both qualified and willing. He could help to that extent, but he could not promise anything. He noted, “They are apparently interested in the Gospel, but I had the feeling that it was only because they desired to secure help to America. But they are fine people and I would be delighted to find that my impression in respect to their interest in the Gospel is wrong. It may be that in such a manner the Jews will be turned to the Gospel of Christ.”[11] Wally also met with another Jewish couple in Brno and shared with them “the story of the persecution of our own pioneers, and then of their final victory.” He also added, “God has promised the same to the Jews when they recognize Christ as the Messiah.”[12]

In late November, another young Jew by the name of Alexander Jacobs asked Wally for financial assistance to immigrate to Holland. Wally learned that Jacobs was an artist, so he proposed to give the young man a certain amount of money if he created some pictures for their Christmas newsletter. Alexander was very pleased to have the work rather than the charitable donation.[13] One of the most difficult things Wally now faced was the stream of Jews visiting his office in search of help, but he was unable to aid them in any way. As he learned of the atrocious persecutions of Jews, he felt completely helpless.[14] At times, the Jewish people were contacting the office so often that Wally could not complete his regular missionary work.[15]

Various problems began to develop on top of the issues he already faced. Several Jewish doctors went to the mission home and told Wally that they expected increased persecution in Czechoslovakia. They had already received anonymous letters warning them to stop practicing medicine and “get out of the country.” The doctors wanted to take their families to America; however, they were not allowed to take any funds out of the country or to leave the country without first having all their immigration papers in order. The documents could not be secured unless one had at least $1,000 per person deposited in America. The “catch 22” situation made leaving the country nearly impossible for those who did not have the means. The doctors hoped that Wally could deposit funds in America for them. They told him that they would pay him in Czech crowns at double the regular rate of exchange. Wally told the doctors that he “would think it over, but [he] felt that [the request] involved too much of a risk.” He wrote in his journal, “The poor Jews here are frantic. They are entirely surrounded by Germany, and have no place to flee. No nation on earth wants them.”[16]

Wally was very aware that Church members were also suffering from what was happening with the Jewish population. When he had left, the Saints felt abandoned, deserted by the leadership. To make matters worse, he discovered news early that spring that a Church member had been baptizing a number of Jews for a certain sum of money to make a profit from their desperation. Subsequently, Wally knew the man would have to be excommunicated if the rumors were true. He hoped and prayed that they weren’t.[17]

Wally had another Jewish friend, Dr. Mohl, who insisted on being baptized. But Wally did not have good feelings about it. When he visited Dr. Mohl, who claimed that he had stopped smoking, the house still reeked of tobacco. Nevertheless, Wally still thought that he should make every effort to acquaint him with the gospel message. Dr. Mohl had read the Book of Mormon and knew in his head that it was true, but Wally recognized that it had not reached his heart. He kept telling Mohl that he needed to have “a period of probation to test his worthiness.”[18] When Wally was able to help him get to Poland, he was unfortunately sent right back to Prague.

In December 1938, things had calmed down enough that Wally hoped he could bring his family and eight displaced missionaries back to Prague. Martha wrote, “Wally returned for us, and we left beautiful, calm Switzerland after a delightful stay there, to go back to the uncertainty of Czechoslovakia.”[19] The missionaries slowly began trickling back as well. On December 8, 1938, six missionaries from England arrived in Prague. A wonderful reunion ensued, and Wally noted that just two months earlier they had all wondered if they would ever meet again. Two days later, he met all the missionaries in the mission home and outlined the conditions of the country and the policies to be followed as they worked in the already organized branches of Prague, Brno, and Mladá Boleslav.[20]

The brethren then held a testimony meeting in the mission home. Many reported they had experienced great “faith promoting incidents while in England,” and they spoke of how much they enjoyed teaching the gospel in their own tongue. “But they also expressed their thankfulness,” Wally noted, “at being able to return to Czechoslovakia and their determination to work as never before. The work in England seemed to be a good tonic for them, after the difficulties they experienced here just prior to the political crisis.”[21] Even though less than half of the original force of missionaries were able to return after leaving the mission during the crisis, they were able to work and enjoy at least some success.[22] Though Wally had reported no baptisms for the year of 1938 prior to the evacuation to Switzerland, he reported six converts in his year-end report to the First Presidency. While the number was certainly lower than the seventeen from the year before, it was still six more than he had expected.[23]

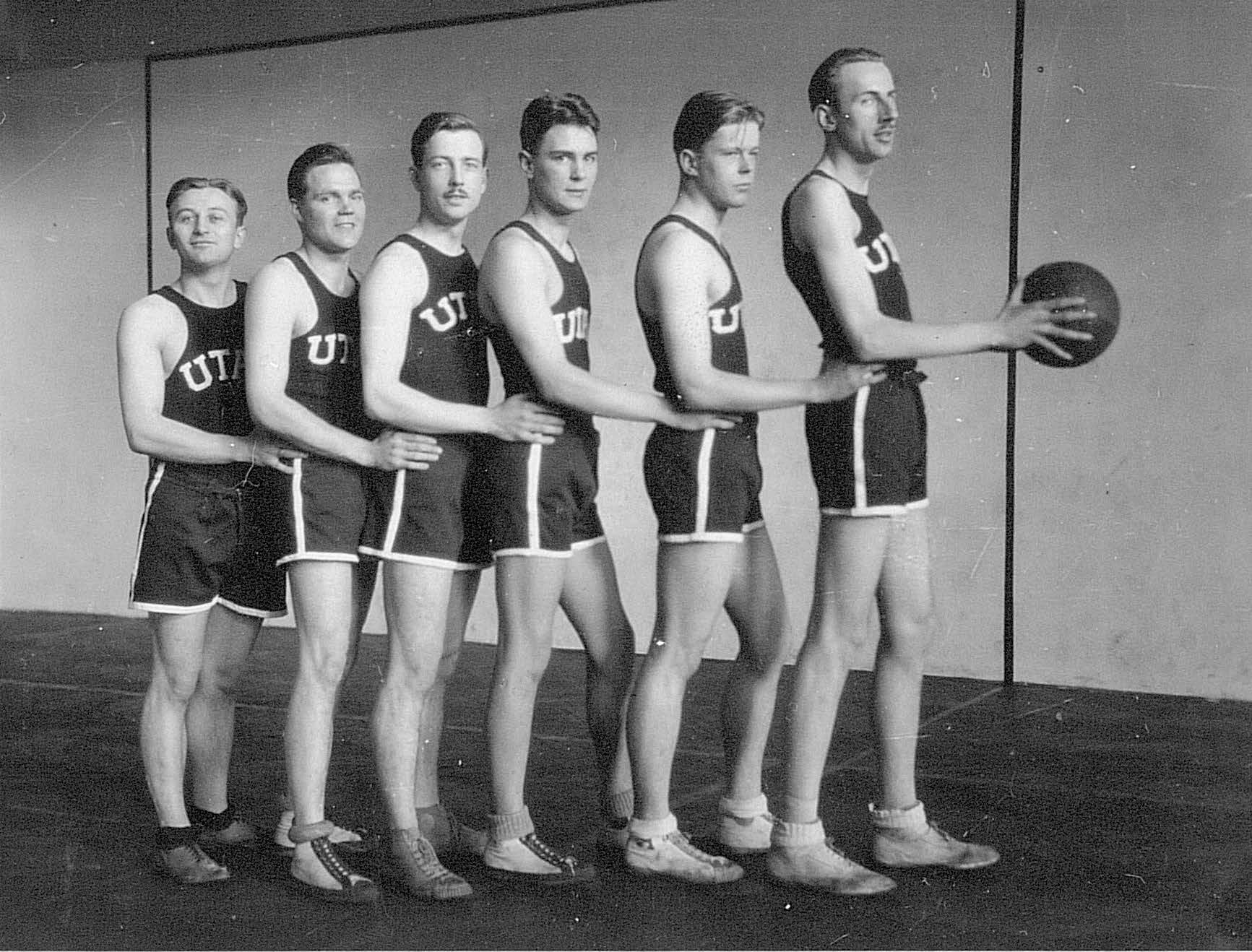

In the Church, Wally picked up right where he had left off. In an effort to revive a mission tradition, “Toronto organized a basketball team and a male quartet to once again attract public attention.”[24] During a Sunday School lesson on December 10 that forty-five people attended, he taught about prophecy and inspiration. “It is through the gospel that all men complied with laws which permitted them to come upon the earth,” he declared.[25] Wally was also still determined to learn as much Czech as possible. One day in January of 1939, he wrote, “I delved into Czech and filled my mind with Czech phrases and gospel material, and then asked the Lord to bless me in my talk for the evening, which I was determined to give without using a paper. The Lord did bless me that evening and I felt his spirit in abundance.”[26]

Once again, the issue of marriage arose almost as soon as Wally returned when he met with a local member who told him that most girls in the branch were only in the Church to try and get American missionaries for husbands.[27] In response, Wally again urged the members to live the gospel as they never had before. The members, in turn, became greatly encouraged, especially since the missionaries had returned to work among them again.[28]

That January, Wally prepared a four-page letter to all Church members regarding the covenants they had made at baptism. He made a list of ten things that were “required of them, and then made it emphatic that unless they were doing their utmost to comply with these simple requirements,” neither the mission, nor the Church, nor the Lord himself would be “pleased with them.” Wally indicated that the amount of tithing and fast offerings they paid during the year was low. Their attendance at sacrament meetings and lectures during the past three months had declined. He had the branch presidents countersign letters of commitment.[29] He called it a “jerk-up” letter that he believed was necessary to boost them up again. “We have worked now with kindness and with diligence for almost three years among some of the members in order to encourage them to greater activity. I finally felt that a definite straight-forward statement of conditions was necessary. I expect some of the weaker ones to be perhaps offended, but most certainly they will not be able to say: ‘I didn’t know what my responsibilities were.’”[30]

First Czech missionary basketball team, 1929. Wallace Toronto (second from left) and Arthur Gaeth (far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

First Czech missionary basketball team, 1929. Wallace Toronto (second from left) and Arthur Gaeth (far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Church members were not the only Czechoslovakians who got a wake-up call that spring. “Through a ploy the Nazi regime made the remaining territory of Czechoslovakia an independent state in early March 1939. By March 15, Germany had a firm control of the entire nation.”[31] Contrary to their assumptions after the Munich Conference, “Czechoslovakia had lost territory to Germany, Poland and Hungary and the remaining Czech lands in Bohemia and Moravia had been seized and renamed the Protectorate” within only six months of the conference. “Czechoslovakia had ceased to exist, but without creating the peace and stability that Hitler and German diplomats had claimed would be the result.”[32] Wally observed, “The ‘up-set’ of March 15 took the wind out of the sails of the brethren.” He wrote about the effect of Nazi control on the missionaries in his journal. “Most of them lost the desire to dig in. Their study hours were not being maintained, neither on Czech nor the Gospel. They wanted to know what the future held for us, for evidently they expected that we would not remain long in the country. This idea I vigorously attacked and then informed them that we were here to stay, that we had asked for additional missionaries, and that they were to let the members know how we felt about it. This seemed to cheer them considerably, and they expressed the desire to plunge into the work again.[33]

Another pose of the missionary basketball team in 1929 with Wallace Toronto (far left) and Arthur Gaeth (left of center). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Another pose of the missionary basketball team in 1929 with Wallace Toronto (far left) and Arthur Gaeth (left of center). Courtesy of Church History Library.

But amidst all the turmoil, Wally experienced some positive upset of his own. On March 4, he had scheduled to speak at an evening meeting when Martha decided that “she had better go over to the doctor’s that afternoon.” Fortunately, it was a good thing that Wally skipped the meeting because on that night, Martha gave birth to healthy, seven-pound baby girl they named Carol.[34] However, despite the joy Carol brought them, her birth coincided with fear brought by the German occupation.

As Martha lay on the hospital bed recovering from Carol’s birth, “there were rumblings of every sort from vehicles large and small riding over the cobblestones, noise of people running and shouting, and even much unrest and chatter among the nurses.” When Martha inquired of a nurse what caused all the commotion, the nurse answered that an unexpected invasion was in progress. Martha immediately called Wally, and he confirmed the terrible news. When he went to see her that afternoon, he assured her that everything was all right, except that the Germans now officially ruled Czechoslovakia. She remembered, “We wouldn’t have to leave the country, however, because the bloodless takeover of the country went very smoothly. Hitler’s thousands of troops had skillfully used this surprise tactic and were in complete control.”[35] Most fortunately, both she and the baby were doing well and feeling fine in spite of the invasion. Wally and Martha then decided to call Carol their “occupation” baby.[36]

As the invasion proceeded, the mission had to immediately make adjustments to comply with the new government to avoid any problems with the Gestapo. Wally advised missionaries to stop tracting, not because it was against the law but because he deemed it wise that they not be any more visible than was necessary. He restricted the elders to teaching and contacting referrals from local church members only. The new government immediately implemented a general ruling that no public gatherings were allowed, which likely came as no surprise. Although the restriction really only lasted a few weeks, it had a long-term effect on the missionary work. Even faithful members felt the pressure of being forced into inactivity. “After this time, social meetings . . . still had to be approved by the government officials.”[37]

The Nazis were always visible. Their constant presence reminded the Torontos that they lived in a war zone. One experience reinforced that reality for Martha on a particular day in the spring of 1939. A group of Nazis “in long lines and black uniforms and black boots . . . were goose-stepping” in front of the mission home in Prague. Marion, just five years old at the time, looked out the window and watched the soldiers march down the road and, at one point, even lift their rifles and shoot over the mission home. Terrified, Marion ran to her mother and “grabbed her around the knees, hiding [her] head in [her mother’s] skirt.”[38] While comforting little Marion, Martha looked out through the window’s lace curtains. Much to her surprise and total alarm, she beheld her three-year-old goose-stepping along with the soldiers. She ran as fast she could to retrieve her little boy amidst the rumbling tanks. From the third floor, Bob had been observing the Germans marching by the house and decided to join them.[39]

The presence of the Nazis virtually always meant danger. And as such, everyone watched them with fear. During a Mother’s Day program, all the members of the Prague branch experienced that tension. Martha described the events that transpired:

The service was drawing to a close but still in progress when the back door of the meeting hall opened, and in stepped a tall Nazi officer. He was very handsome in his striking white naval uniform. The congregation, members and friends alike, froze in their seats. A German officer appearing as he did meant but one thing to us all—arrest and imprisonment. After hesitating a moment or two he smiled and started walking down the center aisle toward Wally, who was sitting in his customary place at the front of the hall, presiding over the meeting. Wally, being very skilled at not showing astonishment, rose and walked toward him and spoke to him in German. Happy to hear his own language, the young man shook his hand and they conversed for a moment. Unable to hear the conversation, we all sat like terrified mummies in our seats. At last, speaking now in Czech, Wally turned to us and announced that this young officer had something to say to us and would speak to us in German. Fortunately my college German was enough for me to understand. “Brothers and sisters,” he began, “I am told that I may speak to you in German without having an interpreter because all of you speak, or at least understand, my language. . . . I am Brother Shrul from Kiel. . . . I am an Elder of the Church. . . . I would like to be accepted and worship with you, if you will allow me that privilege. . . .” By now all the women were in tears and the men were nodding in approval.[40]

After the young officer bore a fervent and moving testimony, he continued, “I come here not on an appointment from my government, but of my own choosing. I come here as a servant of my government. I know we have brought you considerable distress and dismay. We have caused much suffering already. Nevertheless, you and I have something in common which oversteps the boundaries of race, language, and color. You and I have the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Despite the fact that I speak German and you, Czech, yet because of the Gospel, we speak in common terms.”[41] The Nazi officer became a welcome visitor at the meetings in Prague. He “learned some Czech words and phrases that made him feel even more accept[ed by the] small group of Saints.”[42]

European Mission presidents and wives with Elder Joseph Fielding Smith and Sister Jessie Evans Smith (center), Wallace and Martha Toronto (third row, far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

European Mission presidents and wives with Elder Joseph Fielding Smith and Sister Jessie Evans Smith (center), Wallace and Martha Toronto (third row, far right). Courtesy of Church History Library.

On June 3, 1939, Wally received a letter from the First Presidency “notifying him of his honorable release” along with several instructions. “In view of the political changes, it is deemed advisable to attach the Branches of the Church in Czech-Slovak to the East-German Mission. You are therefore authorized to close the office of the Czech-Slovak Mission as of July 1, 1939.”[43] As he read the letter, shock enveloped him. He wondered if the First Presidency was aware that things had stabilized since the German invasion. He decided to “write a letter containing his personal opinion…as to why the mission should stay open” and “planned to take it to the European Mission Presidents’ Conference in Lucerne, Switzerland, on June 12.”

Elder Joseph Fielding Smith of the Council of the Twelve Apostles, who was touring the missions of Europe on assignment from the First Presidency, was sent to preside over the conference. After consulting with Elder Smith, Wally “wrote a detailed report to the First Presidency outlining his views” and suggesting several reasons why “he felt it inadvisable to remove the missionaries and close the mission in Czechoslovakia.” “With the increased tension between nationalities caused by the German invasion, leadership from Berlin was questionable. Since the Czechs were the largest population group affected, if proselyting was to be successful, contact had to continue in their native tongue. In addition, the preparation of mission periodicals was impossible without Czech translators and any other language would be useless.” He continued, “Even though the German government dominated both Czechoslovakia and Berlin, money could not legally be passed between the two countries. Travel between the two countries was equally difficult if Church personnel were allowed to pass back and forth at all. And more than anyone else involved, the Czech members would suffer most from the change.”[44]

Elder Smith agreed with all five of Wally’s recommendations and sent the letter to the First Presidency with his endorsement. Before Wally left the mission presidents’ conference, he had already received a cable from the First Presidency that “deferred his release while consideration was given to the greater problem of extending the mission.”[45] He was thrilled that the First Presidency had “reconsidered, and decided to retain the Czech mission as a separate entity.” Much to his satisfaction, they had decided “not to disrupt the mission, or perhaps better said, make it a part of the East German Mission.”[46] Because the wire from the First Presidency authorized him to remain until August 1, he was able to observe the tenth-anniversary celebration of the dedication of Czechoslovakia on July 24.[47]

Martha did not have the same attitude about leaving as her husband. For her, it was a hard pill to swallow that they were staying. They had received letters from family members at home telling them how excited they were that the Torontos would soon return, and Martha had longed to see them too.[48] But Wally believed the extension would allow them time to make preparations regarding the future of the mission and Church organization in Czechoslovakia.

Elder Joseph Fielding Smith and his wife, Sister Jessie Evans Smith, visited the Czech Saints that June. The Smiths “were enthusiastically accepted and drew missionaries and members alike to them.”[49] During their visit, Elder Smith “stated that he expected more trouble in Europe and was of the personal opinion that the members of the Church should continue to gather to Zion to escape the on-coming disasters. They should not be prevented from going to America if they have an opportunity.” Wally wrote, “He also reminded us that the Church has two great obligations, first, to leave no man without excuse, that he had not had a chance to hear the Gospel, and second, to gather in the seed of Israel.” Elder Smith emphasized how important it was for the missionaries to “bear their testimonies forcefully wherever they went,” even if the result was a severed friendship. “This,” he explained, “is our chief responsibility and calling.”[50]

On July 21, 1939, the last baptisms in the country took place before World War II in Brno. Brother Dees baptized Otakar Karel Vojkůvka and his daughter, Valerie, who had just turned eight years old.[51] When Valerie decided to be baptized, she was very sick with pertussis, or whooping cough. Wally was concerned about her health and was not sure it was wise to let her be baptized. She declared that if she was not baptized on that day, she would never be baptized. He could not deny her request. As she came out of the waters of baptism, she was healed of her cough. She was somewhat correct about that particular day, that it would be her last opportunity: all the missionaries, who had the Melchizedek Priesthood and could therefore baptize, were forced to leave the country the following week. There would be no one who had the power to baptize and confirm in Czechoslovakia again until 1943.[52]

After Elder Smith confirmed Brother Vojkůvka, Wally confirmed little Valerie.[53] Three days later, sixty-eight people met on a wooded knoll at Karlstejn to celebrate the anniversary of the country’s dedication for missionary work.[54] Sister Smith favored them with a song, and Elder Smith spoke. Elder Smith testified, “I want you to know that I am telling you the Truth. On the last great day we shall both stand at the Judgment Seat of God—you and I—and I shall be there to testify that I told you the Truth.”[55] He then “uttered a beautiful prayer, asking the Lord to bless this people with peace . . . [and] to grant that the missionary work might be permitted to go on unhindered in [Czechoslovakia].”[56] It was a great joy for Wally to spend several days with Apostle Smith and his wife, and he felt extraordinarily blessed to know them.[57]

Regrettably, the Apostle’s plea to the Father for “unhindered missionary work” was unanswered. Within a few short weeks, peace for Czechoslovakia became a luxury of the past.

Notes

[1] Gilbert W. Scharffs, Mormonism in Germany: A History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Germany between 1840 and 1970 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 92. See Alfred C. Rees, in One Hundred Tenth Semi-Annual Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1939), 73, as cited in David F. Boone, “The Evacuation of the Czechoslovak and German Missions at the Outbreak of World War II,” BYU Studies 40, no. 3 (2001): 123.

[2] Toronto, journal, October 2–8, 1938, 274–75.

[3] Toronto, journal, October 16–22, 1938, 283.

[4] Toronto, journal, October 16–22, 1938, 282.

[5] Toronto, journal, October 16–22, 1938, 284.

[6] Toronto, journal, November 27–December 3, 1938, 300.

[7] Toronto, journal, November 13–19, 1938, 295.

[8] Toronto, journal, November 20–26, 1938, 299–300.

[9] Toronto, journal, November 12–19, 1938, 296.

[10] Toronto, journal, December 18–24, 1938, 305–7.

[11] Toronto, journal, December 18–24, 1938, 305–7.

[12] Toronto, journal, April 2–8, 1939, 349.

[13] Toronto, journal, November 27–December 3, 1938, 300.

[14] Toronto, journal, July 4–10, 1937, 120.

[15] Toronto, journal, April 16–22, 1939, 354.

[16] Toronto, journal, November 20–26, 1938, 297.

[17] Toronto, journal, March 19–25, 1939, 345.

[18] Toronto, journal, from February 12–18, 1939, 332.

[19] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 17.

[20] Toronto, journal, December 4–10, 1938, 303.

[21] Toronto, journal, December 11–17, 1938, 304.

[22] David F. Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries at the Beginning of World War II” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1981), 45.

[23] Czech-Slovak Mission Manuscript History, June 21–December 20, 1939, 1, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, as cited in Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 45.

[24] Czechoslovak Mission Manuscript History, June 20, 1939.

[25] Toronto, journal, December 4–10, 1938, 303.

[26] Toronto, journal, January 22–28, 1939, 326.

[27] Toronto, journal, December 25–31, 1938, 308.

[28] Toronto, journal, January 1–7, 1939, 321.

[29] Toronto, journal, February 19–25, 1939, 334.

[30] Toronto, journal, February 19–25, 1939, 334.

[31] Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 45.

[32] Patrick Crowhurst, Hitler and Czechoslovakia in World War II: Domination and Retaliation (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013), 22.

[33] Toronto, journal, April 16–29, 1939, 355–56.

[34] Toronto, journal, March 5–11, 1939, 338.

[35] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 18.

[36] Toronto, journal, March 12–18, 1939, 343.

[37] Czech Mission History, June 20, 1939, 3, as cited in Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 47.

[38] Marion Toronto Miller and Judith Toronto Richards, interview, May 3, 2013.

[39] Bob and David Toronto interview, August 20, 2013, 20.

[40] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 19–20.

[41] Wallace F. Toronto, in Report of the 110th Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 5, 1940; Anderson, Cherry Tree, 19–21 as cited in Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 48.

[42] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 21.

[43] Czech Mission History, June 20, 1939, 13, as cited in Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 49.

[44] Czech Mission History, June 20, 1939, 13, as cited in Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 49–50.

[45] Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries,” 49–50.

[46] Toronto, journal, July 23–29, 1939, 389.

[47] Toronto, journal, June 11–17, 1939, 371.

[48] Toronto, journal, July 9–15, 1939, 379.

[49] Anderson, Cherry Tree, 24.

[50] Toronto, journal, June 11–17, 1939, 370.

[51] Toronto, journal, June 11–17, 1939, 370.

[52] Vojkůvka, “Memories of President Wallace Felt Toronto,” November 9, 2013.

[53] Toronto, journal, June 11–17, 1939, 370.

[54] Czechoslovak Mission Manuscript History, December 31, 1939. Mehr, Mormon Missionaries Enter Eastern Europe, 72.

[55] Toronto, journal, July 23–29, 1939, 388.

[56] Toronto, journal, July 16–22, 1939, 386.

[57] Toronto, journal, July 23–29, 1939, 389.