San Marcos Mormons Embrace Temporal Progress and Development

F. LaMond Tullis, "San Marcos Mormons Embrace Temporal Progress and Development," in Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 129–154.

This chapter reviews Mormons’ basic ideas about progress and development and examines some of the startling ways in which they were applied in San Marcos. Temporal pursuits joined spiritual ones in the Saints’ quest for a better life. We look at literacy, cultural change, membership core, leadership stability, institutional support, and the Church’s further organizational development in Mexico.

Early on, beginning with a small core of first-generation members and later expanding to include hundreds, the Saints in San Marcos developed a Herculean desire to become a literate people and to alter their culture to be consistent with the moral and behavioral tenants of the restored gospel. These changes did not come easily. Nevertheless, in the process, the Saints survived the Mexican civil war, eventually received significant institutional support from Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, and then saw the culmination of everyone’s efforts in the creation of stakes (an organization, similar to an archdiocese, that embraces numerous congregations or wards). Finally, a culminating prize came to the Mormon congregations throughout the land—the construction of their most sacred edifices, their temples.[1]

When reflecting on their own history, Mormons frequently cite the Lord’s statement that “by their fruits ye shall know them” (Matthew. 7:20). Frequently, this invites people to examine their inner spiritual ability to distinguish good from evil and rise to a higher plane of existence.[2] However, from the beginning, the general Mormon population has also understood Christ’s dictum to link temporal accomplishments with spiritual insights in a hoped-for trajectory of progress and development.[3] Eternal progress begins here and now. Thus, most Mormons understand the fruits to which the Lord referred to as involving the totality of a people’s life.[4]

The Lord forcefully buttressed this idea when he focused on his people’s need to acquire knowledge and intelligence, which Mormons understand to be the basis for obtaining wisdom, a most desirable godly trait: “Whatever principle of intelligence we attain unto in this life, it will rise with us in the resurrection. And if a person gains more knowledge and intelligence in this life through his diligence and obedience than another, he will have so much the advantage in the world to come” (Doctrine & Covenants 130:18–19). Moreover, the Lord adds the following challenge: “It is impossible for a man to be saved in ignorance” (D&C 131:6).

With such admonitions, it is unsurprising that Mormons have adopted a predilection for work—work to acquire spiritual authenticity, work to obtain temporal wellbeing, work to gain an education, work to create and enjoy all the positive technological and scientific advances consistent with a Christ-centered life, work to acquire intelligence and knowledge and apply them to daily life in homes and communities. These fruits are not only desirable, they are harvestable. However, they don’t just fall off the trees of life to be picked up with little effort. They must be cultivated, nourished, sought after, and engaged with tremendous desire and energy. Work. Indeed, Mormons have developed a gospel of work, a gospel to “make evil-minded men good and to make good men better,”[5] and to improve their conditions of life along the way.

In a practical sense, aside from trying to learn to live within a gospel culture, for illiterate and semiliterate members of the Church in Mexico, a natural, indeed, pressing need was to pursue an education, to become literate so that as a minimum they could read and understand the faith’s sacred texts and have greater economic security from which to provide for their families. It was a daunting task.

Literacy and the Mormon Idea of Progress and Development

Humanity had a long, rough and circuitous road to become literate. In the beginning, ambitious people had to invent writing symbols to express their oral capabilities, a complex system of communication itself being an astral feat. The desire to communicate symbolically was so intense that it appears that self-taught “linguists” developed independent scripts at least four times in human history: in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Mesoamerica, and China.[6] In the early years, Mormons even developed their own phonemic “Deseret Alphabet” as a means to help the Church’s disparate members from a plethora of nationalities learn English.[7]

Developing a language script is one of the seminal achievements of humankind. Learning how to use it, even getting permission to use it, almost rivals the linguistic creation itself. During the European Middle Ages, religious authorities proscribed teaching, knowing, or even talking about a written language if it involved learning to read the Bible, which would be too disruptive of traditional authority.[8] Later, when the access issue was resolved through the Reformation, only those with economic means had the wherewithal to learn to read the Bible or anything else. For the vast majority of humanity, work in the fields began at around six years of age. Learning a language script was not necessary for survival even if one had energy after a day’s work to think about wanting to. Such was the situation among numerous early Mormons in Mexico, including many of the first members of the branch of the Church in San Marcos.

Joining the Church ruptured the tradition of illiteracy. Contrary to the Catholic elite in medieval and later times, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints wanted its members to read and study its sacred texts. Accordingly, many early Mormons—Anglo as well as Mexican—learned their alphabets and how to use them to sound out words by studying the Book of Mormon and their other revered texts.[9]

Following up on these learning biases, the Church, from its beginning, invested enormous resources in institutions to help educate its members—elementary schools, high schools, junior colleges, and universities—thereby fostering an ethic of not only acquiring an ability to read and write but also of pursuing voluminous opportunities during a lifetime of learning.

By the turn of the twentieth century, there were at least three elementary schools functioning in the Anglo-American Mormon colonies in Chihuahua. Soon, in Colonia Juárez, the Church even constructed an academy for secondary studies. Later, as the membership among ethnic Mexicans grew in central Mexico, the Church moved to establish and maintain schools there until the Mexican public education system improved substantially.[10]

In central Mexico, member-led foundational initiatives began before any general Church educational efforts were undertaken. In 1944, Bernabé Parra and his friends set the mold for all that followed,[11] cementing among themselves and Mormons in other congregations in central Mexico the idea that it was God’s will to become educated, which meant, at a minimum, the ability to read and write.[12] Beginning in Parra’s San Marcos home in 1944 with six students, by 1959 the first LDS-related school for ethnic Mexicans had 211 elementary students in much enlarged scholastic quarters.[13]

These and subsequent efforts have immensely helped members of the Church in their efforts to improve their lives temporally and spiritually, aiding, in particular, San Marcos members in countless ways to become greater contributors to the Church; more faithful adherents to its doctrines of salvation; and more substantial social, economic, political, and moral contributors to the communities in which they live.

Success, popular proverbs tell us, has many fathers, while failure is an orphan. The San Marcos “Church School,” founded in 1944 and morphed into Héroes de Chapúltepec in 1961, has at least two conflicting accounts of parentage: the one that Bernabé Parra and Amalia Monroy have advanced, and an alternative one that Agrícol Lozano Bravo has put forth. Let us briefly consider each.

Bernabé and Amalia and the San Marcos School

As we have seen, Bernabé Parra transmuted from an ambitious but illiterate campesino to a politically astute businessman who unselfishly lent his talents and resources to building up the community of Mormons in San Marcos. Along the way, he became not only literate but also one of the area’s greatest sponsors of literacy—and not just for Mormons. For example, while he was president of San Marcos’s Department of Public Works (obras materiales), he used his position to guide the building of a public school in the community. In his honor, community officials installed a commemorative plaque at the municipal (county) magistrate’s office next to the now old school.[14]

For Parra’s role, he had married well when he united with Jovita Monroy. Without the overarching cultural influence of the Monroy family and its resources on his developing life, it is hard to imagine how he could have become so accomplished. Ambition, latent talent, conviction of the truthfulness of the Restoration, and opportunity combined to make Parra a towering influence among Mormons and beyond. One of the best expressions is the “Church School” in San Marcos, a work to which Parra dedicated himself as an excommunicated Mormon, a status he endured for a decade (ca. 1936–46).

Parra’s great respect for his mother-in-law Jesusita frequently brought to his mind her educational hopes for her progeny. As early as 1915, Jesusita had expressed her longings to mission president Rey L. Pratt. “I must procure a place,” she said in her letter, “where I may educate my little granddaughter, my little Conchita, the jewel of my dear son, as also Carlota.”[15] Writing just a month following the Zapatista execution of her son Rafael, Jesusita, still in deep mourning, was nevertheless already looking ahead generationally, even to the yet unborn, attempting to give them the best launch she could into the future.

In the spring of 1944, Bernabé Parra had not forgotten Jesusita’s sentiments when his mistress Amalia Monroy took him to a window in their home that gave a view of the town’s public school. Throngs of unkempt children shouting obscenities (groserías) at each other were milling about. “I cannot send our children to school there,” she must certainly have expressed. Until then, Amalia had homeschooled her two boys, then about ages seven and five, but knew she had to turn them loose to pursue a formal education. But where? Not there![16]

Putting together his sons’ needs and Amalia’s desires, Bernabé was easily convinced. They began looking for a Church member to employ as a private teacher for their children and a few other elementary-aged youngsters. They would use their home as a base.

The couple settled on Luis Gutiérrez, a relative of Bernabé’s and the brother of Nicolás Gutiérrez, whom Parra had supported on a mission,[17] a particularly studious soul who read “many books.”[18] Apparently, Nicolás’s brother Luis was cut out of the same mold. Parra paid him sixty pesos a month for his teaching services.[19] Later, Luis Gutiérrez, writing not only as a beneficiary of welcomed employment but as an astute observer of the local educational scene, spoke of Bernabé, and by implication of Amalia, as being “full of charity for humanity.”[20]

The “Parra School,” which later was called the “Church School” and which finally became known as Los Héroes de Chapúltepec, began on 29 March 1944 with six students meeting in the home that Parra shared with Amalia. The six were Benjamín Parra, Bernabé Parra, Jr., Enrique Montoya, Calixto Cruz, Felipa Cruz, and Virgilio de la Vega, although others are mentioned as having joined quickly thereafter.[21] Accordingly, the following year the school enrolled forty-five students, increasing in size to over two hundred students by 1959.

Bernabé and Amalia paid Luis Gutiérrez’s salary, purchased the necessary curriculum materials, and provided the space. More students began applying for admission. Parra could see the bills mount and, eight months following the beginning of the first classes, in December of 1944 he tendered a formal application through mission president Arwell L. Pierce to the LDS Church’s education department for incorporation into its system of educational oversight and support.[22] Over the next seventeen years, the Church offered piecemeal funding from time to time and underwrote the cost of a school building on land that Parra donated, but not until 1961 did it take on the full costs of maintenance and operations.[23]

Clearly, observers had seen the need,[24] but Church and Mexican bureaucracies and decision-making centers were both cautious and arcane. The result? With only occasional contributions from the Church during the seventeen-year interregnum, Parra, the Monroys, the Villaloboses, other members, the students, and student’s parents raised the money to operate their school. They organized a “school board” (patronato escolar) to meet Mexican legal requirements so their elementary school graduates would be accepted into the government’s secondary schools, held fundraisers of every kind, charged tuition, assessed members fifty centavos a week as a kind of “school tax,” and for seventeen years accepted the continued donations of Parra, Benito Villalobos, and the Monroys.[25]

Part of the Church’s delay in embracing a good idea was its quandary about the pressing educational needs of its members throughout Mexico, many of whom, at the time, were illiterate. Anything the Church did in San Marcos would likely need to be generalized. Could the Church sustain the cost, and if so, what expenditures elsewhere would need to be curtailed in order to do so? What about the Church’s other burgeoning worldwide needs? Internally, various decision-making groups had disparate views.[26]

Another element in the delay directly involved the Mexican government. Given that civil war-era proscriptions against religiously sponsored schools were still in force, how could the Church work legally in educational matters, or quasi-legally—or even extra-legally—but with political support? All these matters had to be worked out, culminating finally in the formation of a separate entity funded by the Church to sponsor the effort. The Sociedad Educativa y Cultural S. A. was born[27] and, modeling its efforts on the San Marcos School, soon established, maintained, and operated more than thirty elementary schools in Mexico for Mormon children and others who, depending on behavior and moral conduct, qualified to attend.

A Contrasting View on the San Marcos School: Agrícol Lozano Bravo’s Role

For twelve years, from about 1935 to 1947, long before he was set apart as the first bishop of the Ermita Second Ward and later ordained a patriarch,[28] Agrícol Lozano Bravo was the San Marcos Branch president. By all accounts, he excelled in aiding the Saints and supporting his large family of thirteen children, a significant majority of whom became not only lifetime Mormons but distinguished themselves in their Church service and in education and other ways. Whether from genes, culture, accidental opportunity, or purposeful design, Agrícol Lozano Bravo and his wife, Josefina Herrera Hernández, created one of the most significant pioneer families in the history of the Church in Mexico. Most of these families’ patriarchs and matriarchs had humble origins that they overcame through a monumental desire to excel once they had accepted the gospel. This desire appears to have been a perpetual guidance to the Lozano Herrera extended family.

Agrícol Lozano Bravo was San Marcos’s branch president when the Church excommunicated Bernabé Parra. He was branch president when President George Albert Smith visited San Marcos and restored Parra’s priesthood after Arwell L. Pierce had rebaptized him. He was in San Marcos when the “Church School” began.

In his 1974 interview with Gordon Irving, Lozano Bravo wanted it known that the role generally accorded to Bernabé Parra with the school (summarized previously) is unwarrantedly placed.[29] Indeed, Lozano Bravo took credit for a series of events that got the school founded and then had the Church take over its maintenance and operations under the fictive guise of an independent Sociedad Educativa y Cultural S. A.

According to Lozano Bravo, his efforts began during the reign of Mexico’s president Lázaro Cárdenas del Rio (1934–40). A number of San Marcos members, unmoved by the economic nationalism and agrarian reform policies that Cárdenas espoused[30] (a return to the rhetoric of the Revolution) and frightened by their president’s welcoming León Trotsky and other Russian socialists into Mexico, approached branch president Lozano Bravo with a special request. Would he get a school started for their children? Caught up in the propaganda that Cárdenas was a communist and was working to establish communism as the country’s prevailing ideology and that he would use the schools to infiltrate these scary ideas into the minds of the children, some San Marcos Mormons wanted an alternative educational venue for their youngsters.[31]

The branch president consulted with his counselors, Ezequiel Montoya and Nicolás Gutiérrez, and they were thrilled with the idea. Lozano Bravo then traveled to Mexico City to solicit the support of mission president Arwell L. Pierce (1941–50). Pierce told him to create an official request (solicitud), signed, notarized, and with supporting documents (all translated into English), to be sent to Salt Lake City. Pierce would then write a cover letter and send it off. Clearly, the request was in line with Pierce’s own assessment of the educational needs of the Mexican Saints.

The Church authorized the school on the following basis: Headquarters would pay 50 percent of the cost of construction and sustaining the school, with the other 50 percent coming from branch members and users of the school’s services. A quota of 50 centavos per person weekly was established for branch members. This was the first LDS church-sponsored school in the whole of Mexico outside of the Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and Sonora.

Parra’s role was to grease the skids with governmental authorities. Because of his political acumen, he was highly successful, and on this count, Lozano Bravo paid Parra great compliments. However, the first classes, Lozano Bravo affirms, were not held in the Parra home but rather in the Monroy home, where they used the hall where sacrament meeting was held and a few additional rooms, doing so until a new school was constructed.[32]

Which View Prevails?

Without detracting from Agrícol Lozano Bravo’s heroic service to the Church over many decades, clearly there are many inconsistencies in his recollections about the school, even accounting for his being seventy-eight when Gordon Irving interviewed him in 1974. All other accounts stipulate that the school moved from the Parra home to the old, then decrepit, LDS church building that the Mormons had constructed years before. Classes continued in that venue until the Church constructed a new school in 1957, funded entirely from headquarters, on adjacent land Parra donated for that purpose.

Construction for the new school commenced on 24 January 1955 and terminated in 1957 with the inaugural celebration occurring on 11 July of that year. Mexican government and public school officials and members of the Church attended.[33] All during the construction, the school’s 171 elementary students continued to meet in the old chapel and its adjacent classrooms.[34]

By the mid-1940s, when the idea of a school was circulating, sacrament meetings and other church gatherings had long ceased to be held in the Monroy home. These meetings had all moved to a first and then a second church building the Saints had constructed from their own will, grit, and ingenuity, with little funding from Salt Lake City. Thus, Lozano Bravo’s claims that the Monroy home rather than the Parra home was the seat of first educational encounter for a few Mormon children is clearly in error.

Despite Lozano Bravo’s initiative as early as 1940 during the Cárdenas administration and fully four years before anyone else was talking about a San Marcos School, he seemed to concentrate his views on the early 1960s, when the Church did indeed take over the San Marcos School, as we have already seen. Lozano Bravo paid scant attention to the twelve years that preceded the takeover.

Lozano Bravo’s efforts probably were influential to the Church eventually assuming responsibility for the school. It is less likely that these efforts coincided with the private initiative, funding, and support that Bernabé Parra and others generated in 1944 and sustained for twelve subsequent years.

Education and Institutionalization

In terms of consequence, it matters less who did what than the fact that these efforts furthered the moral, ethical, and educational development of Mormon children in San Marcos in the mid-twentieth century when the Mexican school system was highly dysfunctional. Those who benefitted from the school’s existence and, indeed, their descendants for several generations will unlikely forget the educational trek that began under private initiative and humble circumstances more than three quarters of a century ago.

Returning to the general role of education in the life of Mormons, one sees the gospel infusing a longing among members to progress and develop and improve their personal lives as well as their capability to serve others. The Church is now in its sixth generation in Mexico, and each generation appears to have made improvements over the preceding one consistent with opportunity and enhanced desire. In English, the hackneyed phrase “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” suggests a fierce longing to progress that does not necessarily await institutional help, governmental or church. Yet hundreds of thousands of Mexico’s Saints whose pioneer forebears did indeed pull themselves up by their bootstraps are now beneficiaries. They have the example of Mexico’s Mormon pioneers in addition to the benefits of enhanced governmental educational services and the Church’s continued educational emphasis, such as through its Perpetual Education Fund, to foster children’s capabilities to integrate with a developing economy.[35]

In each successive generation, Mexican Mormons have availed themselves of opportunities that increasingly have come their way. Accordingly, despite the Church’s completely closing the educational initiatives in 2013 that nurtured the San Marcos School[36] into becoming perhaps the best elementary school in the Tula Hidalgo municipality, launching hundreds of children into a better life, San Marcos children still push on to excel. It is a pattern throughout the Church in Mexico.[37]

Among Mormons, with notable individual exceptions, greater religiosity is associated with higher levels of education, thus facilitating the institutionalization of a faith where people think of “progress and development” as including improvements in their relationship with God.[38] All this facilitates the process by which institutionalization associated with greater spiritual integrity occurs.[39]

Cultural Change

Wherever and whenever the gospel of Jesus Christ has implanted itself in societies, it has done so on a bed of prescriptions and proscriptions—people’s cultures[40]—that already orient individual lives. The gospel does not exist as an isolated and independent social construct. It embeds itself in and, in important ways, alters the customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a given people who otherwise might define themselves independently by national, racial, ethnic, or social groups. Over time, the struggle is for the people of each generation to discover the purity of the gospel and progressively define their lives in terms of a “gospel culture” that takes precedence in key areas over their inherited secular cultures.[41]

National or folk cultures tend to be a powerful warp on people’s thinking, encouraging them to believe that what they do and say and how they do and say it (not to mention the reasons behind both) are, if not totally God’s will, then certainly the best that humankind can offer. It can be a trap, convincing people to think that what they are is the epitome of God’s will for them and that all other humans are inferior. From this cauldron of self-deceit and arrogance, the Lord takes people as they are, embedded in whatever way in the cultures of their times, and through His teachings—His gospel—seeks to make them into new beings of faith and commitment, adherents to a new culture, a gospel culture informed by “a distinctive way of life.”[42]

That the gospel has flourished well in diverse cultures and times attests to its possibility of being a faith for nearly all cultures,[43] the most likely exception being the trajectory that leads people to become rabid, fundamentalist terrorists.[44] However, even under the best of circumstances, sometimes the possibility and the practice of developing a gospel culture are hard to match up. Gospel living requires cultural liberation from the confines of some aspects of whatever ethos has embraced it to the expansiveness of a culture that focuses people’s attention on the concept of eternal life and how to obtain it. It matters less what people wear and eat or whether they sport facial hair or play soccer or football than what they are doing about God’s commandments. They have to decide what entails obedience, righteous living, modesty in dress and behavior,[45] and kindness to one another in a community striving toward a Zion where knowledge and wisdom combine to produce a people who can live with God. That, it appears, is what happened to the Mormons’ fabled city of Enoch.[46]

As the gospel spreads among nations and cultures in modern times, which national culture should prevail? Until a half-century ago or less, the prevailing thinking among North American Mormons of Anglo-European descent was that they had it, that they truly embraced a gospel culture. In some ways they certainly did. However, they confused a lot of ephemeral baggage for the gospel.[47] People in several other cultures have done the same. It has taken time to weed out ephemerality so that gospel tendencies in all cultures that direct people’s attention to Christ-oriented behavior, obedience, and progress are magnified in light of the restoration.

In addition to understanding the doctrines of salvation and the Atonement of Christ, Mormons in all nations and cultures, as they work to embrace their faith, will progressively see the gospel as a binding cultural overlay of their respective national identities. Thus, with constant and careful attention to the essentials that unite them, Mormons can proudly be Mexicans, US Americans, Brazilians, Japanese, Russians, Angolans, Filipinos, or whatever nationality and be less concerned about what separates than what ties them to Jesus Christ and makes them eligible for the array of blessings the gospel promises the faithful.

Cultural Constancy, Change, and Institutionalization

Aside from cultural ephemeralities that may be alien to a gospel culture rather than simply an interesting but unimportant expression of human living, all cultures appear to have laudable elements that may tap into the primordial instincts of people who see themselves as children of God. As an illustration, the Mexican practice of ancestral bonding would certainly seem to qualify. For twenty-first-century Anglo-American Mormons in the United States, such powerful bonding sentiments usually require the surrounding walls of a sacred temple.

Ancestral bonding in Mexico is played out publicly the first and second of November of each year (the Day of the Dead), wherein families link with their deceased through storytelling and graveside visiting in the various panteones throughout the land. However, it is more. Recall that as soon as the Monroy children emerged from the waters of their baptism, they immediately wanted to reenter and be baptized for their nearly always-thought-about progenitors. Recall that at their martyrdom, Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales were said to have even prayed for their yet unborn descendants. The idea of ancestral and descendant links rises to such a level of importance in Mexican culture that it may approach universal religiosity.[48] That is certainly a cultural constant easily aligned with a gospel culture.

All these things aside, change toward embracing a gospel culture is a fundamental aspect of becoming a people truly embedded with God. Most faithful Mormons just keep trying, the perhaps trite but nevertheless penchant question frequently surging in their minds, “What would Christ have us do?” For the early members in San Marcos, this change required their painful attention to the Savior’s teachings about chastity and sexual morality. It required them to address backbiting and rumormongering. They had to address their alcohol problem in light of the Mormons’ Word of Wisdom (Doctrine and Covenants 89) and the constant need to be caring for one another in all conditions of life. Magnificent people rise to these challenges of change. Many in San Marcos rose grandly.

Among Mormons, the doctrine of repentance is a powerful motivator for cultural change and renewal toward gospel living. At least it ought to be.[49] The Saints in San Marcos worked long and hard at it, and, despite their stumbling and frequently awkward passage, many arrived to a point where the gospel was a complete part of them. On such a foundation, the Church in San Marcos became institutionalized, proceeding through a process by which its doctrines, mission, policies, vision, action guidelines, codes of conduct, central values, and eschatology associated with the restoration became integrated into the culture of leaders and members and sustained through time by an organizational structure.

Membership Core and Leadership Stability

A frequently voiced folk proverb in English reads, “When the going gets tough, the tough get going,” meaning that when situations become mortally menacing or difficult, the strong rise to the challenge and work harder to meet it.

Any new beginning for the Church that enjoys “tough members” truly is a godsend. For one thing, they do not wilt in the face of the nearly inevitable persecution. For another, they work doubly hard to inculcate the norms and values of their new faith, to change their lives, their attitudes, and their beliefs toward embracing a gospel culture, even when it becomes more difficult than they may have anticipated at their individual baptisms.

Almost inevitably, Mormon pioneers in every land have suffered varying degrees of persecution, including, in San Marcos, the martyrdom of native leaders. Every pioneer, whether the first member in a given locality or the first of a family anywhere, nearly always faces hard decisions about what she or he will give up in order to accept and pursue the new life that has captured heartfelt sentiments.

In the face of persecution, those who retain a decision to change religiously and culturally find their nerves steeled and resolve hardened. They work overtime to teach their children and grandchildren not only gospel basics but the cultural traits of honesty, hard work, fidelity, rectitude, doing good to others, forgiving enemies, and becoming educated, all of which form a part of what they feel ought to be associated with the gospel culture they are trying to learn and adopt. There is a lack of warring “Hatfield and McCoy” families,[50] with their spiraling retribution and revenge that not only corrodes the heart and damages the soul but costs human lives and produces societal disintegration.

A strong membership core profoundly blessed San Marcos, particularly in the lives of the Monroy family, and more particularly in the person of Jesusita Mera, one of the grandest matriarchs in the history of the Church anywhere whom the author has had the pleasure of encountering. When Jesusita’s daughters started investigating the Church, she did not disown them. At first, she objected to their time with the foreign missionaries, but then she examined the evidence and joined the Church, resolving “never to be defeated.” When her son was lost to an execution squad, she collapsed in despair but shortly arose to give direction, support, moral example, and physical strength to others. Faced with running from her persecutors or standing her ground so that the Church would have a fighting chance in San Marcos, she chose the latter, eventually earning the respect of thoughtful townspeople of whatever degree of persuasion. She took in orphans not even of her bloodline. She used her financial resources to help many others.

Although from a relatively privileged class economically, Jesusita spent her years building up others rather than climbing a figurative rameumptom[51] to cast aspersions on the “lesser people,” a nearly universal social-class practice that allegedly makes the privileged feel good about themselves. Jesusita moved as quickly as she could into a gospel culture and taught others by precept and word to do likewise. In part because of her “ministry,” other strong families emerged—Montoyas, Villaloboses, Moraleses, Parras, and Gutiérrezes. There were others.

With a strong core in place, members in the San Marcos Branch resisted the overtures of Mormon schismatics, in part because the members had pushed gospel learning in the early years. Some members learned to read and write by studying the Book of Mormon. Others aggressively sought out all the literature the Church had published in Spanish and studied it. Some learned English in order to expand the literature they could consume. They held testimony meetings under all kinds of circumstances, using the time not only to express their heartfelt convictions but also to tell what they had or were learning about gospel principles. Strong people do this hard work because it is their inclination to know for themselves what their hearts tell them is true. This also gave impetus to the school that the Mormons established so that, along with academic learning, their children could learn proper moral behavior and something of how the gospel of Jesus Christ ought to be expressed in members’ homes, in their communities, and in their church.

Institutionalizing the gospel in any locale becomes infinitely more probable if strong members bless its efforts from the beginning. San Marcos members, all their personal faults and trials notwithstanding, in many ways created a laudable mold from which others could emerge with accelerated progress.

Institutional Support and Outcomes

A survey of Christian churches in the United States lists thirty-five denominations (which includes numerous subpersuasions) with membership of over 2,500 each.[52] The same publication lists 313 religions for the same region if one counts as doctrinal bases belief in one god, many gods, no god, or god as represented by animal spirits, alien groups, or psychoactive substances. It is likely that other countries have similar nearly unfathomable variations, particularly in Mexico, where storefront churches pepper the urban landscape everywhere.

Within Christianity, one also sees great variation with respect to centralized direction. For example, among the Churches of Christ[53] central direction is nonexistent. The Churches’ byline emphasizes that they “are undenominational and have no central headquarters or president. . . . Each congregation . . . is autonomous, and it is the Word of God that unites us into One Faith.”[54]

Regarding a centralized guiding hierarchy, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a polar opposite of the Churches of Christ. Composed mostly of lay clergy at local and regional levels who come from bewildering varieties of life, it is a president-prophet and a council of twelve Apostles, aided by scores of other “General Authorities,” that hierarchically direct local leaders and therefore the whole Church. Through semiannual general, regional, and “stake” conferences, seminary classes, institute programs, myriad publications on leadership and administration of church affairs, the Internet (https://

Aside from fundamental doctrinal issues, the centrally directed Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints strives for its members to have a common understanding of being “disciples of Christ.” Accordingly, numerous teachings emanate from headquarters on social, spousal, and parental relations and ancestral attachments as well as personal conduct and other categories designed to inculcate a gospel culture among Mormons. The rapid increase in the number of Mormon temples (Mormons’ most holy edifices, which now number more than 150 worldwide) that foster these teachings and inculcate conviction and testimony in members’ hearts are the apex of spiritual institutional support.

Absent such a central direction and support, the Church in its tens of thousands of localities could develop different practices and even beliefs on a range of issues depending on ethnic, family, ancestral, language, and national ties and local leadership prerogatives. It therefore would likely fragment into numerous subdenominations and lose the coherence it mostly now enjoys. In the days of nonattention from central headquarters in Mexico, in part because of a civil war and the Cristero uprising, we have already seen how divergent groups emerged (e.g., Margarito Bautista and the Third Convention).

Mission president Rey L. Pratt was the central link between headquarters in Salt Lake City and local members in the early years of the Church in San Marcos. He was a spectacular personality in his dedication to the Mexican Saints and in his ability to communicate with them. Fairly, one may say that through him the Church had an affectionate following, partly for the restored gospel it embodied but also partly for Rey L. Pratt himself. Because of his position as mission president and the direction his superiors gave him, we may call Pratt’s service “institutional support.” Such support tided the Saints through transitions amidst local leaders’ personal shortcomings and failures. It gave them comfort through their tragedies and persecution. “The Church cares about us.”

Pratt’s Institutional Support

Pratt’s institutional support marshalled and directed local missionaries, placed foreign missionaries on the scene when possible to teach and disseminate doctrines of the restoration, and sent Agustín Haro and other leaders from more mature branches in San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco on various rescue missions to Church members in San Marcos. The teachings, the priesthood ordinances, and, to some extent, even new patterns of social interaction came to San Marcos via institutional support.

There was more. In my mind’s ear, I hear Pratt saying, “You want to build a chapel? OK, I’ll see if I can get funding for the metal roof.”

“I can’t visit you now, but you can expect a letter of support and instructions from me every week. Follow them carefully and heed the words of your branch president.”

“Be careful not to be misled by designing men. Follow the prophet. We are working hard to get more material to you in your native Spanish so that you may be better instructed, especially during times when we cannot be with you.”

“Love one another as Christ loves you. Do good to each other. Support one another through your trials and tribulations.”

Construction Programs

Later, the central Church constructed a new church building and school for the San Marcos Saints, aided them in their educational pursuits, and instituted helpful programs to assist the poorer members in their sometimes-desperate search for food. It established “health missionaries” to work on public health and maternal and infant care through the local Relief Societies and to train young sisters in the rudiments of these fields.[55]

New LDS chapel, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 1974. Courtesy of Laura Smith.

New LDS chapel, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 1974. Courtesy of Laura Smith.

One of the underlying assumptions of the Mormon way of life is that, aside from understanding the doctrines of salvation, the gospel is best understood through the prism “By their fruits ye shall know them” (Matthew 7:20). For Mormons, this does not extend a license to savage people with whom one disagrees, as is so often done in the name of Christ among various religious persuasions and their political offshoots.[56] Rather, it is a call to help one another reach each person’s potential as a child of God. Accordingly, the phrase vigorously persuades Mormons to engage in “good causes” and to extend a helping hand to those in need, to help them grow and develop spiritually; physically, and socially; and to prepare themselves to be economically productive citizens wherever they live.[57]

A clean, functionally appropriate edifice in which to worship and engage in other activities to improve members’ spiritual and social lives gives evidence that “the Church is here to stay.” It encourages people to redouble their commitments. It helps the Church to become institutionalized.

Agricultural and Health Services Program

The agricultural and health services program gained traction in San Marcos with the Church school there. Less than a decade after the Church assumed funding for the school, it launched a complementary agricultural and health services missionary program (1973) that Dr. James O. Mason and his associates Mary Ellen Edmunds and Edward Soper had put together.[58] Someone had noticed that in San Marcos and environs (as elsewhere in Latin America among some of the Church membership) prenatal and postnatal care for mothers and infants did not meet “church standards.” Infant morbidity and childhood mortality rates were alarmingly high.

In 1972, many people in San Marcos, young and old, had died from typhoid fever. A disease called sarna (insect transmitted) was a scary concern—“purple eruptions in the skin, like boils, which eventually could become fatal.”[59] Laura Smith, a health services missionary, notes, “Other major concerns were diarrhea, gripa, stomach pains, fevers and diabetes. Many sisters and investigators were also interested in prenatal, infant and child care.”[60] The agricultural and health services missionaries gained enthusiastic traction.

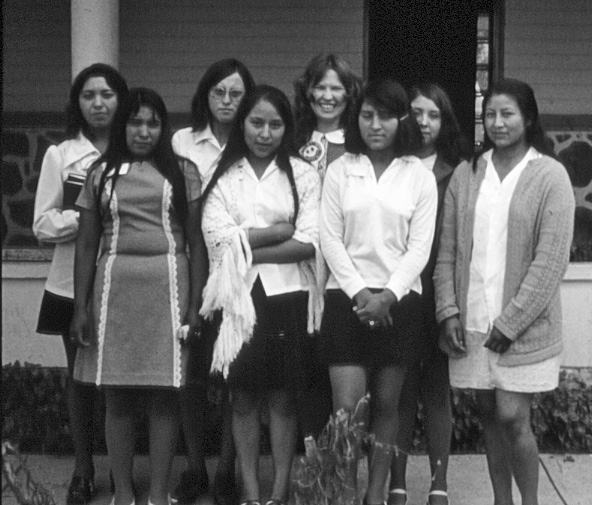

Institutional support that put health services missionaries in San Marcos to work on medical and nutritional problems among members and their friends created a vehicle. However, it did not “start the engine” or give minute guidance on how to drive. The missionaries had to figure that out for themselves. In San Marcos and the surrounding region, the pattern was to select young female members from each branch of the Church and train them as assistants. Then, on a weekly basis, the missionaries traveled from village to village, made contact with their assistants—who, by then, had already made appointments with interested people—and together went about the task of improving the health of the members. In 1975, the author visited a Relief Society meeting in Santiago Tezontlale where the sisters were vigorously discussing materials that the health services missionary and her assistant had taught them about.

Health Services missionary aides, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Training day, 1974. Front row: Sara Abigail González, Josefina Caudillo, Josefina Domingas García, Areopajita Serrano. Back row: Elizabeth García, Regina Pachaco, Elena Tovar. Courtesy of Laura Smith.

Health Services missionary aides, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Training day, 1974. Front row: Sara Abigail González, Josefina Caudillo, Josefina Domingas García, Areopajita Serrano. Back row: Elizabeth García, Regina Pachaco, Elena Tovar. Courtesy of Laura Smith.

During the 1970s, considerable enthusiasm for health services existed among Mormons and their friends in the state of Hidalgo. In some of the meetings, scores of people—mostly women—showed up. Never mind that some of them were illiterate. They could speak and hear and learn orally. They must have, because in a few years public health indicators among Church members improved greatly.

This was an ambitious outreach program to help members and others help themselves. In Hidalgo, health services missionaries worked in Church branches in Pachuca, Tulancingo, Ciudad Sahagún, Tepatepec, Guerrero, San Lucas, Santiago Tezontlale, Tezontepec, San Marcos, Conejos, and Ixmiquilpán. They also extended their activities to areas where formal branches had not yet been organized, including Atotonilco, Cruz Azul, El Carmen, Iturbe, Magdalena, Presas, San Lorenzo, San Miguel Vinho, Tlahuelilpan, Totonico, Tula, and Zimapán.[61]

A membership better informed on matters of health and nutrition appears to give people both the strength and the will to extend themselves in their new faith. Institutionalization is thereby enhanced.

Organization of Stakes

The pinnacle of local organization among Mormons is the “stake,” with its affiliated (usually six to twelve) local congregations called “wards” and “branches.” A transformation from a branch to a ward and a district to a stake requires considerable institutional support for initiation and maintenance. One of the most ambitious efforts of which this author is aware occurred in central Mexico in November 1975. Fifteen new stakes and ninety-six wards were created in a single day, including a San Marcos Ward (now affiliated with the Tula Mexico Stake).

Mormons view this massive creation of new stakes as a truly Herculean effort. Elder Howard W. Hunter, then of the Council of the Twelve Apostles; his assistant Elder J. Thomas Fyans; and four “regional representatives” interviewed more than two hundred priesthood bearers as possible new leaders. They “set apart” (conveyed) the mantle of authority and responsibility to “45 members of stake presidencies, 288 members of bishoprics for 96 wards, 36 members of 12 branch presidencies, and about 150 high councilors.”[62]

In San Marcos and elsewhere, Church support from headquarters has aided, bolstered, guided, reprimanded, and sustained the members. It is hard to imagine that in just a few generations the members could have accomplished so much without it.

Building on a bedrock of repentance—fitfully, despondently, hopefully, and eventually successfully—San Marcos members turned their attention to bettering their temporal lives in the here and now and to taking personal responsibility for as much of their lives as they could. As an example, they rejected the old adage of “If God wills it” (Si Dios lo quiere), so culturally ingrained during centuries of apathy and defeatism born of myriad forces, some extremely oppressive. They became temporal-development activists with a long, generational view as they worked to become literate and provide opportunities for their children to excel educationally.

Regarding personal accountability, strange expressions such as “The book fell away from me” were replaced with phrases like “I dropped the book”[63] as people took more responsibility for some of the problems they got into or that happened to them. People began to believe that not everything was out of their control, that they could take initiatives to solve problems and better their lives. Mormonism was a natural ally of such thinking. Thus, with a strong membership core such as the Monroy family and Bernabé Parra, members could adapt their culture to be more consonant with a Zion people, and the central Church could give assistance that helped to accelerate the temporal development of its members in San Marcos.

True, In San Marcos, the Church’s institutionalization took time, but it ultimately had proper personnel and a proper trajectory to bring it about. The Mormons there have now accelerated their exceptional progress. Not surprisingly, the region has produced a relatively large number of local, mission, and area leaders for the Church and one General Authority. Many of these individuals have served the Church not only in Mexico but worldwide. What the genes of the martyrs have bequeathed is the subject of the next chapter.

Notes

[1] As of this writing, thirteen temples have been constructed in Mexico: Ciudad Juárez, Colonia Juárez, Guadalajara, Hermosillo, Mérida, Mexico City, Monterrey, Oaxaca, Tampico, Tijuana, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Veracruz, and Villahermosa. The first, Mexico City, was constructed in 1983; the last, Tijuana, in 2015. “Statistics,” Temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, http://

[2] See Robert L. Millet, “‘By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them,’” in The Sermon on the Mount in Latter-day Scripture, ed. Gaye Strathearn, Thomas A. Wayment, and Daniel L. Belnap (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 215-29.

[3] The classic case to how this linkage on progress, development, and religious conditions played out in early Protestant Christianity is Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons and Anthony Giddens (London: Unwin Hyman, 1930).

[4] See Dean L. Larsen, “Self-Accountability and Human Progress,” general conference talk, April 1980, https://

[5] David O. McKay, Millennial Star, October 1961, 469, cited by Royden G. Derrick, “By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them,” LDS general conference, October 1984, https://

[6] See, for example, Stephen Chrisomalis, “The Origins and Coevolution of Literacy and Numeracy,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy, ed. D. Olsen and N. Torrance (Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, 2009), 59–74.

[7] Stanley S. Ivins, “The Deseret Alphabet,” Utah Humanities Review 1 (1947): 223–39.

[8] In general, see A. G. Dickens and John M. Tonkin, eds., The Reformation in Historical Thought (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985).

[9] Illustrative for Anglos is Ammon Mesach Tenney, 1844–1925, whose story was written by LaMond Tullis and can be found at http://

[10] Barbara E. Morgan, “Benemérito de las Américas,” 89–116.

[11] Clark V. Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” ch. 3.

[12] For a strong argument of San Marcos being the model, see Clark V. Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” chap. 3. The effects of education generally on a society are reviewed by John W. Meyer, “The Effects of Education as an Institution,” American Journal of Sociology 83, no. 1 (July 1977): 55–77.

[13] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 75.

[14] Minerva Montoya Monroy, email with photo attachment to LaMond Tullis, 21 September 2016.

[15] María Jesús Mera Vda. de Monroy to President Rey L. Pratt, 17 August 1915.

[16] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 65–66. Bernabé Jr. has his father taking the initiative after looking out the window of the apartment over his store. Bernabé Parra Monroy, oral history, 17.

[17] Bernabé Parra Monroy, oral history, 13.

[18] Bernabé Parra Monroy, oral history, 17.

[19] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 66.

[20] “Historia de la escuela Héroes de Chapúltepec,” Church History Library, 1.

[21] “Historia de la escuela Héroes de Chapúltepec,” Church History Library, 2; and Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 66. Bernabé Parra Jr. remembers the first students as being himself, his brother Benjamín, Felipa Cruz, Calixto Cruz (in 2008 president of the Tuxtla Gutiérrez temple), Virgilio Reinoso, Moisés Barrón, Virginia Barrón, and Enrique Montoya. Parra Monroy, oral history, 18. The notes from the “Historia de la escuela Héroes de Chapúltepec,” 1, are probably more reliable. In sixty-eight years of Bernabé Jr.’s memory, names from several years may well have morphed into that first year. Minerva Montoya Monroy informs us that, as far as her ancestors are concerned, the first student was Enrique Montoya, not Alfonso Montoya, as stated in other sources. Email to LaMond Tullis, 21 September 2016.

[22] Mexican Manuscript History, Church History Library, under the date of 31 December 1944.

[23] Joseph T. Bentley, interview by Richard O. Cowan and Clark V. Johnson, 9 March 1976 and reported in Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 73–74.

[24] Arwell L. Pierce, president of the Mexican mission from 1941–1950, authorized the text of one of the final paragraphs of his annual mission report, which reads, “The Branch at San Marcos, Hidalgo, has made formal application for a Church School. We believe that several church schools should be established in well-selected places so that our Mexican children may be trained in Church ideals and faith by LDS teachers.” Mexican Mission Manuscript History, report of 31 December 1944, LDS Church Archives. For more on the singular role that Pierce played in the Mexican Mission, see LaMond Tullis, “A Shepherd to Mexico’s Saints: Arwell L. Pierce and the Third Convention,” 127–57.

[25] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 70–73.

[26] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” ch. 4.

[27] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” ch. 4. Clark Johnson has studied the internal workings of the LDS Church and its relationship with the Mexican government in regards to multiple actors and complex decisions giving rise to the creation of the Sociedad Educativa y Cultural S.A.

[28] Biographical information listed under “Familia Lozano,” “Mormones en México,” Sapienslds (blog), 23 December, 2013, http://

[29] Agrícol Lozano Bravo, oral history, interview by Gordon Irving, typescript, Mexico city, 1974, LDS Church Archives, 8.

[30] For a scholarly treatise of this period, see Marjorie Becker, Setting the Virgin on Fire: Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán Peasants, and the Redemption of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

[31] Agrícol Lozano Bravo, oral history, interview by Gordon Irving, 8–9.

[32] Lozano Bravo, oral history, 8–9.

[33] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 74.

[34] Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 77.

[35] See Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Perpetual Education Fund,” Ensign, May 2001, 52–53; and John K. Carmack, A Bright Ray of Hope: The Perpetual Education Fund (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004).

[36] The influence of the Church’s flagship school in central Mexico is discussed by Barbara Morgan, “The Impact of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Américas, A Church School in Mexico,” Religious Educator 15, no. 1 (2014): 145–67.

[37] From 2011 to 2013, I visited scores of Mexican-member homes whose children confirmed others’ widespread observations that “progress and development” have now become a near universal aspiration among Mormons in Mexico.

[38] Stan L. Albrecht and Tim B. Heaton, “Secularization, Higher Education, and Religiosity,” Review of Religious Research 26, no. 1 (September 1984): 43–58. Stan L. Albrecht, “The Consequential Dimension of Mormon Religiosity,” BYU Studies 29, no. 2 (1989): 57–108. In this, Mormons are an anomaly. The dominant tendency among many other faiths is noted by Michael Shermer, How We Believe: Science, Skepticism, and the Search for God (New York: William H. Freeman, 1999), especially 76–79.

[39] The process by which the Church’s doctrines, mission, policies, vision, action guidelines, codes of conduct, central values, and eschatology associated with the Restoration of the gospel becomes integrated into the culture of its leaders and members and sustained through time by its organizational structure.

[40] That culture profoundly shapes the evolution of societies whether they are in stasis or change is amply demonstrated in the symposium that Harvard University’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs conducted in 1999, which emerged as a book by Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P. Huntington entitled Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (New York: Basic Books, 2000). Frequently, some traditional values do not change commensurate with other values that underpin an evolving culture, which, for this monograph, highlights the constant struggle people have in finding and living a gospel culture as their convictions of its necessity grow. For a discussion in secular terms, see Ronald Inglehart and Wayne E. Baker, “Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values,” American Sociological Review 65 (February 2000): 19–51.

[41] Arturo DeHoyos and Genevieve DeHoyos, “The Universality of the Gospel,” Ensign, August 1971, 9–14.

[42] Dallin H. Oaks, “The Gospel Culture,” Ensign, March 2012, 42.

[43] See Tullis, Mormonism: A Faith for All Cultures.

[44] For a disturbing discussion of general implications, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996).

[45] A stellar discussion from a young Jewish woman is worthy of everyone’s attention. Wendy Shalit, A Return to Modesty: Discovering the Lost Virtue (New York: The Free Press, 2000).

[46] See the Mormon canonical text the Pearl of Great Price, Moses 7.

[47] A robust discussion of elements of this conundrum is by Wilfried Decoo, “In Search of Mormon Identity: Mormon Culture, Gospel Culture, and an American Worldwide Church,” International Journal of Mormon Studies 6 (2013): 1–53.

[48] Samuel M. Brown, in his article “Believing Adoption,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2013): 45–65, especially in the last two pages, argues that on generational bonding the early Mormons in New York, Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri had cultural sentiments more akin to those I have described for Mexico than for contemporary US Anglo-American Mormon culture.

[49] Dallin H. Oaks, “Repentance and Change,” Ensign, October 2003, 37–40.

[50] Refers to a feud between two families—Hatfield and McCoy—of the West Virginia and Kentucky areas that lived along the Tub Fork and Big Sandy River. They were engaged in a blood feud so adversarial that it has entered the lexicon of America folklore as an example of disintegration and loss over issues of justice, family honor, and revenge. At least twelve members of these two families were killed in revenge clashes. See Otis K. Rice, The Hatfields and McCoys (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1982).

[51] According to the Book of Mormon, a rameumptom was a high tower or stand that socially and economically privileged individuals could climb and from which they could look down on the poor masses as they recited rote prayers of thanksgiving for their privileged status (Alma 31). This ancient practice is most likely found in every society.

[52] “35 Largest Christian Denominations in the United States,” last updated 30 June 2008, http://

[53] The Churches of Christ emphasize that they are unaffiliated with the denominational church known as “The United Church of Christ.”

[54] “The Churches of Christ,” www.church-of-christ.org.

[55] Lori Smith, interview by LaMond Tullis, Orem, UT, 3 June 2014.

[56] As an example and for a discussion of the comments of Pastor Robert Jeffress of the First Baptist Church of Dallas, Texas, about Mormons as “cultists,” see Darius A. Gray, “Wherefore by Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them,” published 14 October 2011 and updated 14 December 2011, http://

[57] A fine example of this is seen in a 1980 BYU devotional address by David B. Haight, a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. “By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them,” 7 December 1980, http://

[58] For general information, see David Mitchell, “Agricultural and Health Services Missionaries: A New Way to Serve the Whole Man,” Ensign, September 1973, 72.

[59] Lori Smith (health services missionary), “Notes on San Marcos, Mexico,” 3 June 1974–1 January 1975, 2, copy in author’s possession.

[60] Lori Smith, “Notes on San Marcos, Mexico.” Sarna, if treated, is rarely fatal. It is likely that those who died “of it” did so from ancillary complications around the infection sites. See “Sarna,” Center for Young Women’s Health, http://

[61] Smith, “Notes on San Marcos, Mexico,” 1.

[62] “Fifteen New Stakes Created in Mexico City,” Ensign, January 1976, 94–95.

[63] The passive expression (Se me cayó el libro—The book fell away from me) sounds strange in English because, in this case, one among a multitude, the book was responsible for its collision with the floor, not the person who held it.