Prelude to the Martyrdoms

F. LaMond Tullis, "Prelude to the Martyrdoms," in Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 51–64.

The Monroys’ new religion was a startling viral introduction into the settled Catholic ambience of San Marcos, disturbing the village’s “homeostatic equilibrium”[1] and threatening to undo age-old patterns of social relations and political arrangements that ordered not only who got what but also who gave the orders and who obeyed and for what reasons. Unlike in San Pedro Mártir—and perhaps Ixtacalco and several of the villages nesting at the base of the massive, picturesque, and anciently symbolic volcano Popocatépetl in central Mexico (where Mormonism took early root in the late nineteenth century)—Protestant versions of Christianity had not made a significant impact in San Marcos, had not, in a sense, “prepared the way.”[2] Thus, in San Marcos, Mormonism presented itself not only as a social irritant but also as a first, startling nonindigenous doctrinal competitor to Catholicism. In time, some of the village folk considered it a cancer they had to excise in order to avoid God’s calamitous judgment on the land. How else to do it but force the sinners to repent or, failing that, push them out? Or even kill them?

Thus, Mormonism’s presence in San Marcos and the increasing numbers of people embracing it merited “persecution.” These two factors—the new religion and persecution—not only isolated the early members socially but also made them vulnerable within Mexico’s frequently ad hoc arrangements for maintaining social order.

Four additional factors that contributed to the martyrdoms and their aftermath are also worthy of note: (1) The early members’ association with foreigners, especially Americans, such as the missionaries and the Tolteca cement factory’s expatriate worker team, further raised suspicions about whether the members were loyal to Mexico during the upheaval of the civil war. (2) Fueled by rampant rumormongering, the excesses of the civil war itself strained the boundaries of social restraint in San Marcos. (3) The conspicuous position of the Monroys as a relatively well-off family invited Zapatista antipathy. (4) One rabid pro-Catholic Zapatista officer commanded soldiers to assemble a firing squad that putatively legitimized a malevolent deed.

These six factors—the new religion, subsequent persecution, association with Americans, the civil war, the Monroy’s economic position, a Zapatista commander’s decision—largely explain the martyrdoms in San Marcos.[3]

The Volcanic Persecution Begins

Why do people habitually dislike, if not hate and abhor, one another across boundaries of race, ethnicity, nationality, region, clan, tribe, families, religion, politics, and many other social affiliations? Is the human genome hardwired this way? On the other hand, do opinion makers simply ignite us, and we then respond to their rumormongering? By demeaning another, do we embrace the attendant revulsion and fear that play on our insecurities, inferiorities, or objective conditions of vulnerability to make us feel better if not more protected? Does “whipping up hysteria” serve to enhance a negative solidarity of a people, for whatever reason?

Christ certainly railed against these age-old problems. Most Christian faiths at least pay lip service to his teachings on love, tolerance, and a prescribed goodwill of humankind.[4] The enduring problem is that many steeped-in-the-mire bigots emboldened by ignorance and prejudice who self-attest to their own religiosity may attend church for a lifetime but never internalize a Christian or any other like-minded religious sermon. Mobocracy is one result. It has produced millennia of social heartaches.[5]

The Saints in San Marcos gradually began to feel a sadness of loss from prejudice and persecution, ultimately punctuated by the martyrdoms. Yet, in Jesusita’s defiant words, most of the members firmly staked out their position: “Our trials have been great, but so also has our faith and we will not become faint hearted.”[6]

At first, the early members thought they could have both their new faith and their old friends and certainly retain the loving embrace of their nonmember extended families. For a while, it worked that way. For example, the Monroy daughters liked to host parties, and in early March 1914, nine months following their baptisms, they invited a number of friends to their store to plan a big splash for the village’s social scene. At their planning session they chatted about music, drama, and organizing a literary soirée for later in the month that would honor the culturally significant “Name Day” (onomástico)[7] of Benito Juárez, the Benemérito de las Américas. Juárez was Mexico’s only indigenous and arguably best president (1861–72) and was one for whom in the mid-1880s the LDS Church’s crown colony in Chihuahua and in 1964 its then-flagship school in Mexico City were named.[8]

Benito Juárez, president of Mexico from 1861 to 1872. Of Zapotec origin in Oaxaca, Juárez was arguably Mexico’s best president and certainly its most beloved. Courtesy of Google Images.

Benito Juárez, president of Mexico from 1861 to 1872. Of Zapotec origin in Oaxaca, Juárez was arguably Mexico’s best president and certainly its most beloved. Courtesy of Google Images.

Faithful to their plans, on 21 March the planners held a lively public party in the Monroy compound that attracted the participation of numerous young people and even some of their educational mentors. Perhaps the attendees were among the village’s rebellious souls. Traditional, established opinion makers were annoyed, if not jealous, and even spoke of having the participants arrested.

Under this social pressure, little by little even the presumably rebellious youth who fraternized with the Monroys gradually withdrew, leaving the family isolated from its friends.[9] Then persecution became severe.[10] Several people, including Jesusita, warned Rafael to get out of San Marcos to save his life, because of the venomous language in the village and the death threats coming his way. He declined, saying, “Why would anyone kill me if I have done no harm to them? However, if God desires, then let it be done according to Him who is all powerful.”[11]

Some of the Mormon civil-war refugees arriving in San Marcos for resettlement posed a problem. It was hard to abandon what once were relatively stable circumstances for the rigors of starting life over as refugees, even in a safe environment. For some of the evacuees, the severities and uncertainties posed serious psychological and emotional adjustments. For a few, it exceeded their capacity to cope. Among other things, some of the women were not accustomed to hand grinding their own corn into meal for tortillas, as was then required in San Marcos, and some of the men could not stand up to the rigors of the manual-labor employment that Monroy had offered them on his ranch.[12] The male Rodríguez adults—Ixtacalco branch president Francisco Rodríguez and his family—soon left for what they thought would be paid employment as musicians with the progovernment Carrancista army then in control of Tula. As of April 1915, no one among the Mormons in San Marcos had heard from them again. This “Mormon connection” with the Carrancistas and the resulting implied affiliation with the Americans prompted some anti-Carrancista opinion makers in Tula to further spread scandalous views about the Mormons, which became a serious issue when within three months the fanatically pro-Catholic Zapatistas took over the region by military force.

After the martyrdoms, Jesusita was desperate to leave San Marcos and remove her family from the prejudice and persecution that had fallen upon them. She prayed fervently to the Lord for guidance on how “to leave these ungrateful people who [have] rejected the divine light.”[13]

Anti-American Hysteria

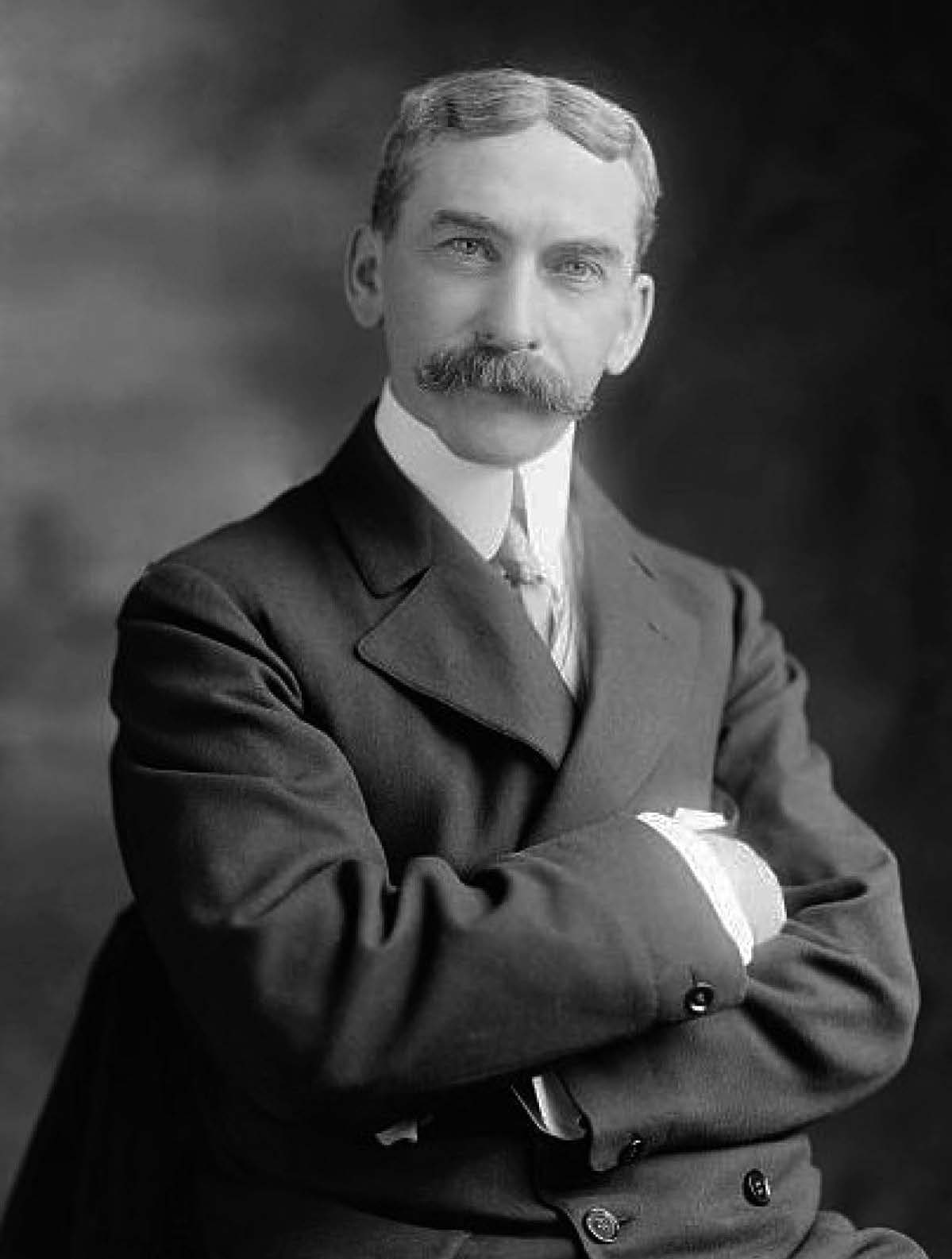

Americans had a bad reputation in Mexico. Mexican president Porfirio Díaz and his close-knit advisors, the científicos, had sold out the country to them and other foreigners, a fact that for years fueled a prevalent hatred for Americans, particularly among the Zapatistas. One analysis showed that “U.S. citizens had controlling interest in 75 percent of the mines, 72 percent of the metallurgy industry, 68 percent of the rubber companies, and 58 percent of the petroleum industry. Combined foreign interests controlled 80 percent of all major Mexican industries.”[14] Mexico had lost Texas to the Americans in 1836.[15] They had seen present-day California, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah ripped off in 1848 at the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo[16] and had, by believable rumor and concrete fact, experienced the nearly constant meddling of the United States in its internal affairs, particularly during 1910–13 under US ambassador Henry Lane Wilson.[17]

In the latter part of April 1914, a rumor, unfortunately founded on verifiable facts, quickly reached San Marcos and flashed through the village: the Americans were tinkering with Mexico’s internal politics—again—and this time at the level of the presidency itself. The “negative solidarity” this created brought people of all political stripes together in one cause, which was to defend their country against foreign meddling, whether French, American, British, or German, in its corporate and military guises. Tula’s chief political officer and finance administrator gathered a large crowd from the municipal capital, San Marcos, and other surrounding towns and led a march on the American-owned Tolteca cement factory. He had admonished the demonstrators to arm themselves with sticks and stones. The emotions were so high that even women and children demonstrated against Americans living in Mexico, fearing they would be a “fifth column” of advance spies to guide another invading US army into their country. The mob had come to lynch the British superintendent, who had wisely left the place the day before.[18]

Henry Lane Wilson, US ambassador to Mexico from 1909 to 1913. Courtesy of Google Images.

Henry Lane Wilson, US ambassador to Mexico from 1909 to 1913. Courtesy of Google Images.

At the time, the United States had indeed planned an imminent invasion of Mexico at Veracruz, which the US Marines ultimately occupied in late April 1914.[19] The invasion was a strike against Victoriano Huerta, the insurgent who, with the collusion of the cashiered US ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, had overthrown Francisco Madero, ordered his assassination, and taken the Mexican presidency illegitimately for himself.

The US presidency had just transitioned from Howard Taft to Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was appalled at what Taft’s administration had been up to in Mexico and sought to undo it by supporting Venustiano Carranza’s constitutionalist army at Veracruz. Everything was complicated. Although most Mexicans grew to hate Huerta, they hated the meddling Americans more.[20] An oft-quoted phrase from the dictator Porfirio Díaz gained additional traction: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States” (Pobre México, tan lejos de Dios, tan cerca a los Estados Unidos).

The general hysteria and the protest at the Tolteca cement factory mobilized the local police, who were easily politicized by one thing or another. The mob had failed to get the superintendent but decided to ambush Roy Van McVey, a member of the factory’s foreign-worker team, at his home in nearby San Miguel. However, the American McVey, who was married to Jesusita’s daughter Natalia, had also fortunately fled the previous day, abandoning his house to the care of his Mexican wife and his store to Casimiro Gutiérrez, the recent Mormon refugee from Toluca.[21]

The police predictably came, ransacked the house and store, found a rifle that McVey had for personal protection, and made the usual threats. Small wonder that Natalia, with her home and store in shambles, fled to find her husband, probably by then somewhere in Mexico City at a place they had agreed upon, and on 20 May 1914, the two departed for Veracruz.[22] After a couple of months, Jesusita traveled to the port city to retrieve her unhappy daughter, leaving McVey in place for a while “until political matters improved in the country.”[23] They did not mend, particularly for Americans. Sometime later, McVey returned to his haunts in the United States and did not see his wife again for many months until she went to be with him in Texas for a time. Later, traveling separately, they both eventually returned to Mexico.

In the meantime, the citizens of San Miguel who not only hated Americans but also the Mexican Mormons who fraternized with them threatened Casimiro’s life. He fled with his family to Tepeji, which left the McVey compound without any occupants. Once in control of the area, the Zapatistas immediately sacked the place again and carted off anything left of value they could find.[24]

Hate born of fear is a powerful motivator of evil causes. Everything for an attack on the Mormons was in place in the municipality of Tula, Hidalgo, needing only the breakdown of civil order and an execution command from a drunken, and perhaps otherwise psychologically unstable, rabidly Catholic Zapatista military commander.

The Revolution Reaches San Marcos

Soon the revolution’s calamity, with its accompanying breakdown of traditional social and political order, fell upon San Marcos and the Monroy family. As elsewhere in Mexico, during this fratricidal conflict, cities, towns, and villages frequently became dueling grounds, as warring factions alternated control while each sought retribution from enemies, real or alleged. Opportunists took advantage of the anarchy to settle personal, political, and religious scores; repudiate debts; sack stores and homes; and sometimes dishonor their female occupants. It was a sad time everywhere in Mexico.

Zapatistas were at war with wealthy landowners and even Mexico’s small middle class. Emerging out of the state of Morelos after sundry alliances to help topple the old dictator Porfirio Díaz, they found their pursuit of land reform and freedom denied under the new regime of Francisco Madero, with whom they had been in an anti-Díaz alliance. In a dizzying array of subsequent temporary alliances, the Zapatistas returned to the battlefield to seek a place for Mexico’s rural poor in what they hoped would become a fair and justly renovated state.

Emiliano Zapata, the founder of the Zapatista movement, eventually codified his demands in the Plan de Ayala. The fifteen terse main points denounced former ally Francisco Madero for his betrayal of the Zapatistas as soon as he became president and demanded immediate implementation of the land reform for which they had fought Díaz and his aristocrats. In sum, the Plan insisted on the restoration to their respective communities of all communal indigenous lands stolen by fraud or outright thievery under the old dictator. Beyond, one-third of the area of large plantations that a single individual or family owned was subject to nationalization and thereafter distribution to poor farmers. Those resisting would have the other two-thirds of their land confiscated as well.[25] Large-scale foreign and national landowners’ initial irascibility quickly morphed into terror.

The Zapatistas were radically Catholic and fiercely xenophobic, despising foreigners for their sometimes-gratuitous attacks on their church as well as the social and economic injustices that fueled their rebellion. They detested any Mexican who associated with outsiders, and they radically opposed anyone preaching an alien religion.[26] Small wonder the Americans feared the revolutionary Zapatistas as, indeed, apparently did most Mexican Mormons in Hidalgo (but not in Morelos), who were anxious about their religious liberties.[27] Unfortunately for Mormons, in 1915, San Marcos briefly came under Zapatista military control.[28]

Just prior to the Villista-Zapatista victory in Tula and their troops’ occupation of San Marcos, the Carrancistas had been in control there. As an occupying force, they had given appropriate guarantees to the civilian population. Nevertheless, they had made a rabid anti-Catholic statement by shelling some of the religious buildings, setting up their officers’ quarters in habitations commandeered from the local clergy, and taking prisoner many Catholic priests.[29] The Zapatistas found all this to be both morally and mortally offensive,[30] and they and their partisans would spare no Carrancista, no matter the cost. No wonder the Carrancista troops had retreated in terror in the face of the Villista-Zapatista alliance that was overwhelming them in Tula Hidalgo and its environs. Fittingly, many Carrancista partisans from the area bolted into the mountains.

Andrés Reyes, a neighbor and one of San Marcos’s Zapatista partisans, informed the Zapatistas that Monroy routinely provisioned the Carrancista soldiers who previously had occupied the town and whom every Zapatista was sworn to kill. He also spread a profoundly false and damaging accusation that Monroy was a Carrancista officer and had a secret arms cache in his mother’s store.[31] Later, some people thought this malicious blathering was retribution for the Monroys having become Mormons.[32] The religious question was never far from people’s minds.

The accusation that Monroy was a Carrancista officer was nothing more than grist circulating in the anti-Mormon rumor mill in San Marcos at the time, perhaps resulting from a few times when Monroy did indeed fraternize with Carrancista officers. However, the accusation that he was an armed combatant was patently false. There is no evidence to support such a charge and, beyond, Monroy—being a dyed-in-the-wool Mormon leader—would have assiduously followed President Rey L. Pratt’s dictum: “Remain neutral. Do not take sides in the Revolution.” Moreover, had Monroy been a Carrancista officer, it is unlikely that a weeping, grieving mother whose six sons the Carrancistas had killed would have come to him seeking solace and spiritual comfort.[33] On this pastoral count, it is much more likely that a few villagers viewed Monroy as an approachable religious figure during times when a traditional Catholic priest may not have been.

The Monroys did have a store well stocked with basic provisions. No matter how much the family may have preferred the Carrancistas to the Zapatistas in the fight to rule Mexico, at a local level they were in a difficult situation. Whichever faction “controlled the plaza” obviously had its privileges, in particular because the Carrancistas and Villistas (and therefore the Zapatistas when in an alliance) had their own printed currency, otherwise worthless except at the barrel of a gun or the fear of confronting one.

Not accepting an occupying army’s uniquely designed currency as legal tender was tantamount to declaring oneself a partisan of the opposing side (with all the attendant consequences).[34] As long as the Carrancistas “held the plaza” in Tula and the surrounding areas, like San Marcos, the Monroys accepted their currency, however reluctantly. They had no choice. They sold them food, for which they received payment in proprietary currency that would be worthless the second the troops left town. Following ancient traditions and necessities, proprietary currency was a thinly disguised way for an invading army to loot the land. It went further. A number of people hurried to the Monroy store to pay their accounts in worthless currency.[35] Many people were looking for whatever advantage they could get.

There was one perhaps avoidable fraternizing excess. Rafael entertained Carrancista officers in his family’s compound, providing meals for them on several occasions.[36] Did he in some way feel forced to extend that social courtesy? Was he obligated, or just found it socially useful, to be visibly friendly, as was the whole Monroy family, with the Carrancista captain Pedro González? Was Monroy simply a closet partisan, hoping that the Carrancistas would prevail in the civil war?[37] Was there some other extenuating circumstance? We do not know.

People held Monroy’s fraternizing with Carrancista officers against him, which also occasioned the arrest of his sister Guadalupe, who had returned to San Miguel to try to retrieve some gold coins that her sibling Natalia had securely hidden in her now-sacked home and store. Zapatistas held Guadalupe prisoner for three days.[38] “Guilt by association” is an ancient ploy justifying all kinds of heinous acts.

Additionally, for three months Rafael and his workers had not been able to carry out any ranching activities at El Godo. It was too dangerous even though Rafael had given to both Carrancista and Zapatista forces “help yourself” signals for his livestock.[39] All the Monroys and some of their employees had taken refuge in the central Monroy compound in San Marcos. While there, someone invited Rafael to join the Zapatistas, thereby offering him a way to get out of a difficult situation. He declined, which seemed to mark him[40] and ultimately foreshadowed his execution, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Notes

[1] The early benchmark that solidified the biological concept of homeostasis to social systems, now subsumed in cybernetics subfields, is Chalmers Johnson, Revolutionary Change, 2nd ed. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1982), especially 55–60.

[2] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 108.

[3] In his superb study of the executions, Mark Grover, “Executions in Mexico,” 8, summarizes five factors: (1) Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales rejected Catholicism at a time when Zapatistas were rabidly pro-Catholic; (2) Monroy’s middle-class status when Zapatistas were preaching “Liberty or Death”; (3) Rafael’s consorting with Americans (members and nonmembers); (4) Rafael’s imputed support of the Carrancistas; and (5) the fact that Zapatistas took out their wrath indiscriminately on medium-scale merchants.

[4] As for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, one impressive statement is from then-Apostle and later–Church president Howard W. Hunter in his address in the October 1991 general conference of the Church, just after the Cold War had ended. President Hunter stated, “This is a message of life and love that strikes squarely against all stifling traditions based on race, language, economic or political standing, educational rank, or cultural background, for we are all of the same spiritual descent. . . . We have a divine pedigree; every person is a spiritual child of God.” A decade and a half earlier Brigham Young University sponsored a symposium on internationalizing the Church and the need for such a philosophy. See F. LaMond Tullis, ed., Mormonism: A Faith for All Cultures (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1978).

[5] Nearly 2.5 million works treating the causes, consequences, and applications of persecution emerge from a simple search on the Internet. One in particular, a seminal treatise laying out the wretched consequences of denying religious freedom through official proscription as well as societal prejudice, is Brian J. Grim, The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-first Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[6] “Carta de Jesús M. Vda. De Monroy,” 8–9, with commentary by Hugo Montoya Monroy, https://

[7] Name days originated in lists of holidays set aside to celebrate saints and martyrs as established by the Catholic Church. It has been a tradition in Catholic countries since the Middle Ages. Various countries have differing lists. See Wikipedia, s.v. “Name Day,” https://

[8] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 9. Benito Juárez’s presidency and his Reforma represented a temporary pause in the power of traditional forces that supported centralized autocracy and economic exploitation of the lower class. Juárez was a founder of Free Masonry in Mexico and as such held strong anticlerical, antitheocratic views that riled the Catholic Church. It is unclear if the party planners, in choosing to celebrate his patron-saint day, were deliberately sticking a spine in the eyes of local clerics and their most rabid supporters. Today, Mexicans generally view Juárez as a national hero. A succinct summary is “Benito Juárez,” Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Gale Group, 2004).

[9] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 9. (Aún así muchos de estos jóvenes se fueron retirando poco a poco y la familia quedó más aislada de sus amistades.)

[10] From the perspective of Jesusita and her daughters, the persecution became widespread and unremitting. A later family member considered that among the poor and middling people in San Marcos and the administrators of the cement factory, the Monroys always had friends. Three or four influential families in their extended numbers were behind all the malice. (Los Monroy tenían muchas amistades entre la gente pobre y de mediana clase y del gerente de la fábrica de cemento. Pero hubo tres o cuatro familias influyentes que declararon cargos en contra de Monroy.) Daniel Montoya Gutiérrez in “Martirio en México,” 6. However, given the configuration of power and prestige in San Marcos, these families’ influence would have far exceeded the relative strength of their numbers, which accounts for the pervasiveness of the persecution that the Monroys felt.

[11] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 32.

[12] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 13–14.

[13] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 28. (Y con todo el fervor de nuestro ser rogábamos [al Señor] iluminara nuestra mente para salir de este pueblo ingrata que rechazaba la luz divina.)

[14] Ramón Eduardo Ruíz, The Great Rebellion: Mexico, 1905–1924 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980), 103.

[15] For differing perspectives, some from the participants themselves, see the following: Richard G. Santos, Santa Anna’s Campaign against Texas, 1835–1836, rev. 2nd ed. (Salisbury, NC: Documentary Publications, 1981), which features the field commands issued to Major General Vicente Filisola; Antonio López de Santa Anna, The Mexican Side of the Texas Revolution, 1836, trans. with notes by Carlos E. Castañeda and illustrations by Carol Rogers and Jim Box (Austin, TX: Graphic Ideas, 1970); and Alwyn Barr, Texans in Revolt: The Battle for San Antonio, 1835 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990). Spanish readers will capture the poignancy of Mexicans’ feelings about this war in Francisco Martín Moreno, México Mutilado (México City: Editorial Santillana, 2004).

[16] The treaty was officially entitled the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic. A good discussion is by Richard Griswold del Castillo, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990). Spanish readers who are interested in seeing how the war played out in Mexico’s northeast in and around Tamaulipas should read Leticia Dunay García Martínez, “Una Guerra Inevitable: El Noreste de Tamaulipas frente a los Estados Unidos, 1840–1849” (master’s thesis, El Colegio de San Luis, A. C., 2013).

[17] See the discussion about Henry Lane Wilson in note 18, chapter 2.

[18] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 10.

[19] Jack Sweetman, The Landing at Veracruz: 1914 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1968). See also the various articles by Mexican authors in La Invasion a Veracruz de 1914: Enfoques Multidisciplinarios (Mexico City: Secretaría de Marina-Armada de México, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México, 2015).

[20] Rey L. Pratt, “Un Mártir de los Últimos Días,” 2, the Monroy family’s translation of Pratt’s “A Latter-Day Martyr,” Improvement Era (June 1918), 720–26, https://

[21] “Carta de Jesús M. Vda. De Monroy,” 4.

[22] Rafael Monroy in San Marcos to Elder W. Ernest Young in Tucson, Arizona, ca. June 2015, read by José Luis Montoya Monroy at a Monroy descendants’ reunion in Salt Lake City, 28 December 2006.

[23] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 11 (mientras mejoraban las cosas políticas del país).

[24] “Carta de Jesús M. Vda. De Monroy,” 8. Hugo Montoya Monroy adds the following: “Natalia and her husband had hidden a large amount of their incomes in the house in the form of several gold coins. In that time, the gold coins—hidalgos—were issued by the National Bank in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Mexican Independence [from Spain]. Guadalupe made a courageous decision to go to San Miguel in order to retrieve this treasure. She was imprisoned by the Zapatistas. When she was released she recovered the hidden treasure for her sister.”

[25] Christopher Minster, “Emiliano Zapata and The Plan of Ayala,” Thought Co., http://

[26] In addition to John Womak, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, cited previously, helpful interpretations may also be found in Michael J. Gonzales, The Mexican Revolution: 1910–1940 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002); Andrés Reséndez Fuentes, “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution,” Americas 51, no. 4 (April 1995); and Frank McLynn, Villa and Zapata: A History of the Mexican Revolution (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2000).

[27] Moroni Spencer Hernández de Olarte links some members of the LDS Church, if not the Church itself, with the Zapatista movement in the state of Morelos. Bradley Hill brought this to my attention in a critique of an earlier version of this monograph.

[28] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 24. We do not know the motivation for the Zapatistas’ being in Hidalgo, outside their normal field of operations, specifically in the municipality of Tula and thereafter in San Marcos. This apparent departure may have been related to their temporary alliance with Pancho Villa’s forces that were operating in the area and the Zapatistas’ reciprocating in some kind of tit-for-tat military cooperation. In any event, during this period, local observers noted the fierce battles occurring between the Carrancistas and Villistas, with Zapatista troops probably loosely organized under the Villista command structure.

[29] The anti-Catholic policies of the Carrancistas were felt elsewhere in Mexico also. Reynaldo Rojo Mendoza, “The Church-State Conflict in Mexico from the Mexican Revolution to the Cristero Rebellion,” Proceedings of the Pacific Coast Council on Latin American Studies 23 (2006): 76–96.

[30] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 19.

[31] Grover, “Execution in Mexico,” 15.

[32] One of the best treatments of the episodes during Monroy’s last week of life is Grover’s “Execution in Mexico,” 6–30. I have drawn from his study for this section of the paper.

[33] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 23.

[34] There were two types of money used alternatingly in San Marcos, one issued by the Carrancistas, the other by the Villistas. Food, especially corn (maize), was scarce, and people did not want to sell what they had but, in any event, were loath to have one faction’s currency on hand when another “took the plaza.” Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 30. Seven pictures of currency in use during the revolution, issued by various bands and putative legal entities, may be seen at “Currency of the Mexican Revolution,” Latin American Studies, http://

[35] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 30–31.

[36] Mark L. Grover cites Daniel Montoya Gutiérrez, who worked for Rafael Monroy, as indicating that Carrancista officers “had eaten at the Monroy home several times and it was this familiarity with the Carrancistas that attracted the attention of the town and resulted in the accusation.” See Grover, “Execution in Mexico,” 2.

[37] Before and during the Carrancista occupation of Tula, Rafael Monroy appears to have been an accorded municipal authority of some kind, perhaps continuing his service in the development of water irrigation systems in the region or even from his earlier appointment as a commander in the Tula police force. In any event, he was a weekly participant in municipal council meetings. The incessant association with the Carrancista occupiers in this and related activities would have turned the rumormongering gristmill against the Monroys. That, coupled with Rafael’s “betrayal” by joining the Mormons, would have accelerated it. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 23–24.

[38] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 21–22.

[39] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 23.

[40] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 32.