The Monroys' Curiosity

F. LaMond Tullis, "The Monroys' Curiosity," in Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 19–50.

In 1912, following a twelve-year absence of missionaries, a condition that had ended elsewhere in Mexico in 1901[1]—LDS missionaries returned in force to Hidalgo, specifically to San Marcos and its environs, to preach the gospel again.[2] There, as in other areas of Mexico after restoring missionary work, the missionaries were searching for old members and working to reestablish the Church among them. In Hidalgo, they generally sought accommodations in San Marcos or Tula and from there fanned out into the countryside.[3]

In these early recovery efforts, on 15 August 1912, two unnamed and “elegantly dressed” young American missionaries entered the Monroy store in San Marcos, not seeking to convert the attendants or owner but rather to purchase supplies and collect information. They were looking for Jesús Sánchez, whom August Wilcken had baptized in 1881 during Apostle Moses Thatcher’s mission to Mexico.[4] How the missionaries knew Sánchez was in San Marcos is lost to time. However, in their pursuit of all the old members throughout central Mexico, the missionaries finally arrived in San Marcos looking for him.

At the Monroy store, the missionaries amply acquired what they sought, as supplies were plentiful. Moreover, astonishingly, the Monroys not only knew Sánchez, but Rafael and at least his sister Guadalupe considered him a friend. (Their mother, Jesusita, eventually came to hold him in great esteem.)[5] Delighted, the missionaries quickly departed for Sánchez’s home where they visited, stayed overnight, and returned on numerous occasions before his death the following year.[6] On each visit, they took occasion to stop at the Monroy store.

The next time Jovita and Guadalupe Monroy spoke with Jesús Sánchez, they stippled him with questions:

“Why were the young Americans looking for you?”

“They are missionaries of the Church of Christ.”

“What do you mean ‘Church of Christ’?”

“Yes, it is the true Church!”

“How is it that the Catholic Church is not the true one?”

With a few follow-up words, Sánchez gave the Monroy women his testimony.[7] If any missionaries were to return to San Marcos, the women asked Sánchez to bring them over to their home for a visit.

Nearly three months after that initial missionary trip to San Marcos, around 13 November 1912, Elders W. Ernest Young and Seth E. Sirrine paid a follow-up visit to San Marcos.[8] They had been to Nopala to call on José Yáñez, who, along with Jesús Sánchez, was also one of the early converts from 1879 to 1881.[9] After their stay with Yáñez, they went on to Tula to see the pre-Columbian ruins there and then to San Marcos to visit Sánchez. Sánchez brought the young men to the Monroy compound, where they found the daughters primed to pepper them with questions.

Jesusita became alarmed at what she interpreted as her daughters’ attraction to rudiments of the Mormon message if not to the missionaries themselves. She prayed that the missionaries would cease coming to San Marcos.[10] Rafael’s wife, Guadalupe Hernández, also voiced her objections to the missionaries’ presence.[11] However, not content with just hearing the missionaries’ response, the stubborn Monroy daughters later borrowed Sánchez’s Bible (the version of Cipriano de Valera) and began to study it in light of what the missionaries had told them.

A friend said to them, “Chucho Sánchez’s Bible is no good. He is a Protestant. If you want to read a good Bible, Tomás Ángeles has one that used to belong to Father Lino, my uncle.”[12]

Tomás Ángeles was also a Monroy family friend, so the daughters went to his house to borrow a proper Catholic Bible (version of Padre Cío San Miguel), so they could make comparisons. They found Sánchez’s Cipriano de Valera translation perfectly acceptable. Later, the Monroy daughters’ brother, Rafael, also asked Sánchez about his affiliation with a church called “Mormon.” Sánchez gave him the same testimonial response he had given to his sisters.

Given Mexico’s class structure at the time, it is remarkable that the Monroys had friends among various social strata. As for Sánchez, he was in a subservient social and economic position to the Monroys, yet they had an amicable relationship, and he certainly did not cower when presented with an opportunity to testify of his convictions. Generally, contacts across the classes were not so cordial and good natured and frequently tended toward exploitation and abuse, which is one reason Mexico had its revolution.

One explanation as to why the Monroys could so easily relate across social chasms despite their having deferential servants and employed laborers is that just one generation ago they had toiled daily as members of the rural life themselves. They still remembered “how it was” for them. They had not had time and had certainly exhibited no inclination to develop the social snobbery that so often accompanies the nouveau riche at whatever level. In addition, the Monroys had a large and relatively affectionate extended family, and not all of its members had prospered as had Jesusita and her offspring. Thus, when Sánchez told them of his religious convictions, the Monroy children were not preconditioned to reject his worldview out of hand simply because he was relatively uneducated and came from a less-advantaged social class.

Through Jesús Sánchez, the attractive young men and subsequently their message began to take hold of the Monroys, first with Jovita and Guadalupe; soon thereafter with Rafael; later with their mother, Jesusita, and her married daughter, Natalia;[13] and then with other members of the extended family. Events surrounding the death of Jesús Sánchez seemed to seal the matter. In life, and then in death, Sánchez continued to imprint what he considered the most important part of his life’s message.

Sánchez’s Death

W. Ernest Young and various missionary companions had begun to make periodic trips to the Hidalgo region, stopping one time, as already noted, in San Sebastian in January 1913 to visit Lionel Yáñez. Lionel was a grandson of Desideria Quintanar de Yáñez, the first female baptized in central Mexico.[14] Regardless of wherever else they visited, the young missionaries always ended up in San Marcos for more conversations with the Monroy family. The Monroys were a magnet. Usually on these visits, the missionaries stayed overnight or longer in Sánchez’s home, but sometimes they also found accommodations in the Monroy home. San Marcos did not have a hotel, boarding house, or overnight rooms for rent. It was a village.

At the same time that the missionaries were making their visits in an attempt to reclaim early members of the Church, Mexico’s national political scene reeked of precursors of a full-blown revolution or, more accurately, a civil war (1910–17) that would radically transform Mexican society, culture, and government. Although the clouds of war hung low over the landscape in central Mexico, the missionaries did not yet feel alarmed.

Some have said that almost inevitably every nation will experience its revolution. In the relatively recent past, England, the United States, and France had theirs. Scores of countries followed. In the last two-and-a-half centuries, hardly a geographic place or race or ethnic people have been unscathed. So it is with Mexico and its revolution of 1910–17, a fratricidal conflict of sufficient magnitude that historians call it a civil war. Around a million lives were lost to battle, disease, hunger, and privation. Some of them were Latter-day Saints.

The Latter-day Saints lived in their villages and hamlets in central Mexico and in their various colonies in the northern states of Chihuahua and Sonora. During the revolution, civil disturbances and armed conflicts shifted from locale to locale, eventually affecting all the Saints. The hostilities disrupted homes and families with attendant loss of life. It was a perilous time for all of Mexico’s residents, as the country struggled to form a new social identity, a new economy, and a new political system.

As the clouds of war began to hang yet lower in central Mexico, federal troops, impromptu militias, loosely organized guerrilla bands, and opportunistic gangsters roamed the land in search of their enemies or booty, first in the south and the north but ultimately in central Mexico, where nearly all the ethnic Mexican Mormons lived.[15] The federal troops, rebel militias, guerrillas, and gangsters took on various names attached to their principal leaders at any given time. Carrancistas, Maderistas, Villistas, Zapatistas, Huertistas, Obregonistas—these are some of them.[16]

In central Mexico, the whipsawing between federal troops and, in particular, Zapatistas afflicted many Mormon families. Sometimes the Saints could not maintain any appearance of neutrality, which Church authorities had counseled them to do. Sometimes the conflict became a pretext to settle old grudges among neighbors. Sometimes members helping members made the difference between life and death. Remarkably, the Relief Societies throughout central Mexico aided members all during the civil war. Equally remarkable was that many of the branches continued to function, their priesthood leaders doing what they could to protect the Saints and care for those who had been hurt or displaced.

The insurgent Francisco Madero and his allied forces had overthrown the decadent, corrupt, and dysfunctional regime of Porfirio Díaz, whose tortured social philosophy had bathed the entire land in a tsunami of discontent. In turn, Victoriano Huerta secretly plotted with US ambassador Henry Lane Wilson to overthrow Madero and arrange his assassination, an act set in motion when Huerta and his principal coconspirators met at the US embassy to sign the Pacto de la Embajada, or the Embassy Pact.[17]

Huerta’s sordid and ultimately naked pursuit of personal power at whatever cost caused US president Woodrow Wilson to recall and subsequently cashier his ambassador and to ultimately refuse to recognize Huerta. Unfortunately, the repugnant episode contributed to the US invasion of Veracruz a year later. Among the less-than-privileged classes, anti-American sentiment rose feverously.[18] The American missionaries began to watch their backs carefully.[19]

In this environment, in March 1913, before the revolution finally reached central Mexico, the missionaries received word that Jesús Sánchez had developed a life-threatening illness. Jesusita Monroy, ever the comforter, accommodator, and compassionate service giver, reached out to her family’s friend and his loved ones. Sánchez’s wife had wanted to bring in the Catholic priest to administer last rites. Sánchez’s daughter Felix respected her father’s religious persuasion and did not know what to do. Jovita and her friend (a family employee and later her husband, the young Bernabé Parra) came to the house also. The Monroys persuaded Felix to send for the missionaries, who had not been around for a couple of months. This seemed natural, given that Sánchez was a Mormon and the Monroys had learned from both him and the missionaries about sacred healings by the laying on of hands. The literate Monroys could write letters, and they knew the missionaries’ address in Tlalpan, so they initiated the invitation.[20] Interestingly, Sánchez’s death-invoking illness did not deter his venting outrage at Madero’s assassination,[21] perhaps a precursor of how most Mexicans now view the role of the despised alcoholic Huerta in the history of their land.[22]

Responding to the request to return to San Marcos, W. Ernest Young and Willard Huish arrived at the train station in Tula that served the nearby American-owned Tolteca cement factory, with its numerous British and American administrators and technical workers. Unfortunately, the missionaries were unable to walk the nearly three miles to reach Sánchez’s home before he died on 29 March 1913. Thus, upon finally arriving several hours following the death, they found Sánchez’s family and the Monroys already grieving. The missionaries had reached their destination too late to perform what the Monroys apparently had hoped would be a priesthood healing.

Young and Huish offered to hold a funeral service the following day, to which the Sánchez family gratefully agreed. For the moment, the missionaries extended what comfort they could to the grieving family and then returned to San Miguel, near the train depot, where they sought accommodations at the home of one of the American cement-factory workers, R. V. McVey. McVey and his wife, Natalia, another Monroy daughter, would both join the Church later.

The following day, 30 March, Young and Huish conducted Sánchez’s funeral. Afterward, Jesusita invited them to her home for lunch, where they, along with her daughters Guadalupe and Jovita, talked about the restored gospel.[23] Their conversations lingered into the evening. Rafael came by, and everyone stayed up late discussing the funeral, what the elders had said there, and what the Mormon gospel that Sánchez had professed revealed about the meaning of life and the eternal journey of the soul. The Monroy daughters were mesmerized. Rafael was interested. Jesusita was delighted with her guests if not their message.

The following day, the missionaries returned to visit the Sánchez family and “found them very comforted.”[24] They stayed on in Hidalgo until 2 April and then took the train back to Mexico City.

A Visit to San Pedro Mártir

As demonstrated by the case of the Monroys, the impact of social relations on potential converts’ decisions to affiliate with the Church could be substantial. It all happened when the Monroy family was on the cusp of social displacement in San Marcos. The Monroys’ association with foreign missionaries, not to mention Natalia’s spousal relationship with the American McVey, had begun to create community commentary. By then, the Monroys may have begun to feel a social distancing that later would become intense persecution. Whether for that reason or because of an irresistible desire to see what Mormons in Mexico were doing, they decided to accept an invitation to attend a district conference in San Pedro Mártir, near Mexico City.

The Church’s San Pedro Mártir Branch was organized in 1907. Under the aegis of its first president, Agustín Haro,[25] and with the assistance of the Latter-day Saints in nearby Ixtacalco, San Pedro Mártir Branch members would subsequently tutor a growing body of Mormons in San Marcos after the full-time missionaries were withdrawn when insurgency morphed into a full-scale civil war.

In 1912, San Pedro Mártir was an excellent example of several locales in Mexico that were first converted to Protestantism before receiving the restored gospel.[26] There was a certain evangelical enthusiasm there, and Mormons in the area tended to be fervent about their new faith. With what they considered a proper Mormon expression of welcoming visitors—one comfortably ensconced within the rubric of Mexican culture—branch members would affectionately embrace the Monroys.

Ever the enterpriser, in May of 1913, W. Ernest Young invited the Monroys to the San Pedro Mártir conference scheduled for the twenty-fourth to the twenty-sixth of the month. In those days, conferences were multiday affairs that many Saints traveled long distances to attend and for which many sought overnight accommodations, mostly in members’ homes. Young was fully aware that the Monroys were acquainted with Mexico City and would have no trouble traveling from San Marcos to attend if they wanted to and no trouble acquiring hotel accommodations while so doing. Young had already alerted the Monroys to the possibility of meeting mission president Rey L. Pratt, by then a legendary figure among Mormons in Mexico and, by all counts, a spellbinding orator. The invitation had the desired effect of initiating a conversation within the Monroy household.

Rafael Monroy’s sisters María Guadalupe and Natalia were interested. Thinking the conference would be in English, Rafael was not attracted but changed his mind when he learned otherwise. The trio journeyed to Mexico City, where they arrived at the mission home not only well before the appointed hour but even before the Mexican mail service had delivered their previously sent letter of acceptance! Young had no idea they were coming and was therefore delightfully surprised, a mood slightly dampened by having to inform them that Rey Pratt would not be at the conference. The mission president was busy trying to get some members out of prison in Morelos.[27]

Disappointed, the Monroys nevertheless accompanied the missionaries to the Saturday session of the conference, where, President Pratt’s absence notwithstanding, they found the messages in general not mesmerizing but certainly interesting, some even compelling. At the conference’s midday pause and before the afternoon session, they were surprised to see the missionaries eating the “humble” food the San Pedro Mártir Mormons had prepared for them and other visitors.[28]

Rey Lucero Pratt, president of the Mexican Mission, 1907–31. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Rey Lucero Pratt, president of the Mexican Mission, 1907–31. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Then there was an electrifying surprise! President Pratt abruptly showed up. Members gathered around him, all smiles. Young introduced the Monroys to him. His gracious and magnetic character was on full display.

Saturday evening the members presented a program of music and dance, with little children participating, they too being important among almost all Mormons. On Sunday, the Monroys witnessed a large number of Mormons and their friends enthusiastically gather for the day’s meetings. In his discourses, Pratt was true to his oratorical reputation. Then there were baptisms near Ixtacalco. Members were confirmed, children were blessed, a Priesthood meeting was held, and ordinations and ordinances were performed. Afterward, Pratt invited the Monroys to the mission home, where his wife had overseen the preparation of a regal American meal.[29]

The Monroys were startled not only at the humble circumstances of the members who attended the conference but also that the gospel fellowship that united them with the Americans could bridge the obvious social-class divisions. However, there was more: the Monroys’ elegant visage notwithstanding, the Saints in San Pedro Mártir had embraced them as if they were family. Not surprisingly, the Monroys not only felt welcome amidst the members’ humble conditions, they also felt loved across any earthly boundaries that national and social cultures habitually taught people to reinforce. Thus the Monroys were astonished, but warmly so. In San Marcos, they had also bridged such social and cultural boundaries. Witness, for example, their relationship with Jesús Sánchez and later, as we will see, with Bernabé Parra.

Back in their hotel room in the evening after two days of whirlwind activity, the Monroys began to discuss and “feel” the days’ events. Sunday evening they could not sleep until very late. All they had listened to and experienced flooded their minds. After sleep finally came, Rafael even dreamt that he was preaching everything he had heard.

Guadalupe, Natalia, and Rafael arose early Monday to catch the morning train at Buena Vista, and when arriving at the Tolteca station in Hidalgo, they saw everything differently. Family members wondered how they could have spent three days in Mexico City without accomplishing any business for their store. Then, in the ensuing days, there was much correspondence, as the Monroys wrote to Elder Young and to President Pratt and received copious replies from both.[30] Perhaps all this motivated President Pratt to schedule a follow-up stay at San Marcos. He wrote to the Monroys requesting to visit them.[31]

Would the Monroys be interested? They may not yet have found appealing a visit from Agustín Haro, the San Pedro Mártir Branch president of humble means, who later would figure large in their lives. However, a visit from President Rey L. Pratt? In three days? Of course!

Baptisms Amidst Conviviality

On 10 June 1913, President Rey L. Pratt and Elder W. Ernest Young traveled to San Marcos as promised. Their gospel discussions with the Monroys and others (seventeen attended their evening meeting) appeared to last until the early hours of 11 June. The Spirit was present and the decisions were quick. Rafael and his sisters Jovita and Guadalupe opted for baptism, which Young performed midmorning on the eleventh in a nearby river. Their enthusiasm must have been elevated; they wanted to reenter the water to be baptized for their forebears, not yet realizing that by then, vicarious ordinances for the dead, a unique Mormon practice, were done only in the Church’s temples.[32] President Pratt probably did the confirmations, performed on the riverbank under the secluded ambience of an enormous cypress tree whose branches pushed out over the water.

issionary Ernest W. Young (back row) baptized Rafael Monroy Mera and his sisters Jovita and María Guadalupe, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 11 June 1913. Courtesy of Church History Library.

issionary Ernest W. Young (back row) baptized Rafael Monroy Mera and his sisters Jovita and María Guadalupe, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 11 June 1913. Courtesy of Church History Library.

However reluctantly, Rafael’s wife, Guadalupe Hernández, came to witness these strange events, as did Jesusita herself. Present also were the Monroy children’s cousins Isauro Monroy, María Carlota Monroy, and Eulalia Mera Martínez. Eulalia would subsequently become Vicente Morales’s wife. Oh, yes, present also was the nineteen-year-old Bernabé Parra, whose larger-than-life role in San Marcos was waiting to unfold.[33] Rafael was thirty-five, Jovita twenty-nine, and Guadalupe twenty-seven. It had been two and a half months since Jesús Sánchez’s funeral. The Monroy siblings became the first people baptized in the municipality of Tula in well over a quarter century.[34]

Among Mormon converts of the time, the Monroy family members were unusual because they were comfortably ensconced in a nascent rural middle class that, with a few notable exceptions, characteristically eschewed the restored gospel’s message. Abandoning Catholic traditions, or in some instances a community’s subsequent Protestant leanings, imperiled a family’s social standing. True, such angst was a problem across all social classes, but its gravity increased with prominent social standing.

The three baptized children of Jesusita were educated and cultured. They were acquainted with a few of the literary and philosophical treatises circulating in Mexico at the time and not only enjoyed parlor music, for example, but the young women also demonstrated it on Jesusita’s piano. The Monroys frequently traveled to Mexico City and its environs to provision their store and enjoy the lights, sounds, and ambience of a relatively large city. Being well acquainted with Mexico’s passenger trains, the family knew how to travel, including which routes and, aside from trains, which lateral conveyances to use. The Monroys had domestic servants; employed laborers on their ranch, El Godo; consorted with foreigners, particularly Americans, one of whom Natalia even married; and were politically well connected.[35]

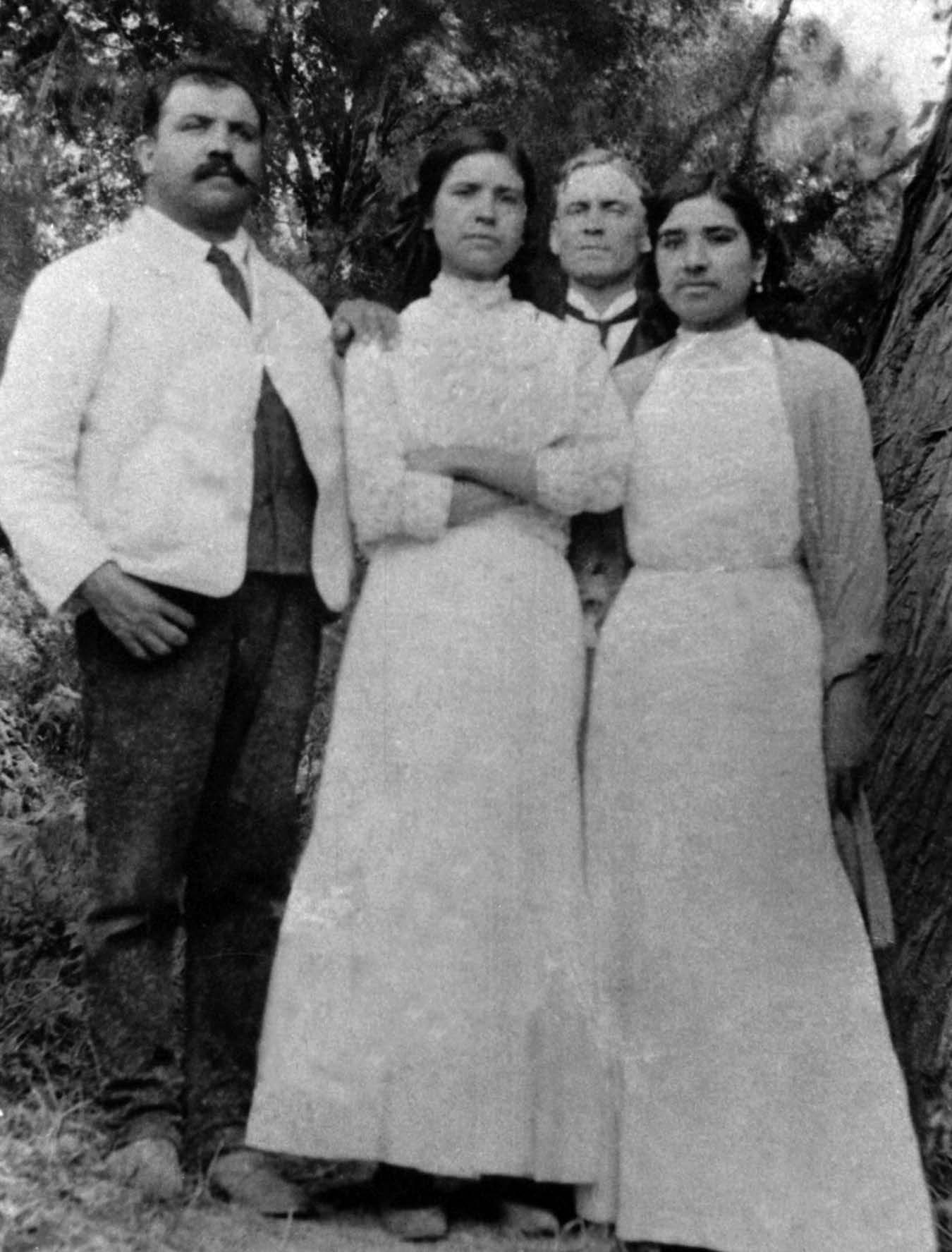

Monroy family in San Marcos Hidalgo, ca. 1913. Rafael, his daughter María Concepción, his wife Guadalupe Hernández, his sister Natalia Monroy Mera, his mother Jesusita, and his sisters Jovita Monroy Mera and María Guadalupe Monroy Mera. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Monroy family in San Marcos Hidalgo, ca. 1913. Rafael, his daughter María Concepción, his wife Guadalupe Hernández, his sister Natalia Monroy Mera, his mother Jesusita, and his sisters Jovita Monroy Mera and María Guadalupe Monroy Mera. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The Monroys’ situation was quite distinct from most rural LDS converts of the time, who frequently were only marginally literate if at all, and who often dressed in the humblest of traditional fashions, females frequently not even wearing shoes, most likely because they could not afford them. Most of these early converts were vulnerable to capricious acts of nature and to political and social abuse as they struggled daily to put bread on the table, sometimes being unsuccessful when disease, the government, or the powerful plowed over their well-being. Like the early Saints in Great Britain,[36] most Mexican Mormon converts of the time were what some called the dregs or the “deplorables” of society. But in time, they assembled a surprise. Many converts, including numerous of their descendants, became stalwarts in the Mormon kingdom and boundless contributors to their communities’ development.

A week following their baptisms, Jovita and Guadalupe, perhaps in Mexico City conducting business related to their store, showed up unannounced at the mission home for a quick visit. Guadalupe had told her sibling about Sister Pratt and the mission home, and Jovita wanted to see everything for herself. They found Elder Young there, perhaps doing nonmissionary activities. The civil war was hindering their missionary efforts, he said, and they were often unable to make planned visits and sometimes did not know what to do. In the meantime, he was carrying three suitcases upstairs to President Rey L. Pratt’s wife, Mary (May) Stark Pratt, who had begun to pack her family’s belongings in the event that the US embassy ordered evacuations from the country.[37]

War concerns notwithstanding, the Fourth of July was about to arrive, and, as usual, American residents in Mexico City planned to celebrate their independence day in Tivoli Park, enhanced this year by a circus at the location. This time, however, American attendance was sparse not only because of the war but also because there was now considerable acrimony between Mexicans and Americans, fostered in large part by US ambassador Henry Lane Wilson’s political machinations. Pratt invited the Monroy family to the festivities, and they all showed up, including Natalia’s husband, R. V. McVey. Astonishingly, by present-day standards, and despite the drunken rowdies in attendance at the festivities, the missionaries “found some nice girls to dance with.”[38] Today it seems strange that they would dance at all.

Ensuing Baptisms Spawn Hostility

In the middle of July, with war increasingly in the news, President Pratt and his family (wife and five children, ranging in age from nine to one) took a ten-day vacation to San Marcos, where they stayed in the Monroy home. For the Monroy family, as well as for their servants and remaining friends, the Pratt family was a major attraction, which included their message about the restored gospel. Within days, Pratt conducted another baptismal service: joining the Church were Jesusita, her niece Eulalia Mera Martínez, and the nineteen-year-old field hand and incipient manager, Bernabé Parra, who had begun to have feelings for Jovita, ten years his senior. Surprisingly, Rafael’s wife, Guadalupe Hernández, was also baptized a week later. All of them echoed Jesusita’s words: “With happiness I accepted baptism in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” adding “and my life changed.”[39]

Aside from their feelings of joy and happiness for accepting the gospel and its ordinances, which was accompanied by alterations in their worldview and their life expectations, the Monroys saw their relationship with the citizens of San Marcos change. The townspeople began to ramp up their criticisms of the Monroys, even to the extent of publically praying for them, working their rosaries daily, and making offerings so that the family would return to its Catholic roots and the Mormons, the foreigners, be banished from the land.[40] That effort proving to be a failure, the public shunning and store boycotts were ramped up, a phenomenon that eventually included even members of the extended Monroy family who withdrew their association.[41] Friends ceased to come by and even refused to receive the Monroys in their own homes.

In the meantime, the Monroys, their close relatives, and Bernabé Parra were content and happy “for knowing that they had accepted the true doctrine of Christ and they rejoiced in seeing themselves as true Christians.”[42] At the time, they appeared to have little realization that, looming on the war’s frontier, their association with Americans would contribute to a catastrophic quandary for them.

While in San Marcos, Pratt became concerned about how to return to Mexico City. The rebels had cut through more rail lines, and transit was being interrupted everywhere except for the line to Veracruz.[43] The war had begun to expand its tentacles even in central Mexico.

Orders for Evacuation

Another district conference was scheduled for 9 August 1913, this time in Toluca, in the state of Mexico. Winds of war aside, President Pratt intended to be there and invited Rafael Monroy to accompany him. By this time, Pratt had not only developed a keen social liking for Monroy but also trust and confidence.

Not wanting to travel alone during increasingly perilous times, Monroy took with him his trusted field managers—Bernabé Parra and Monroy’s nephew Isauro Monroy. They met up with Pratt and several missionaries at the mission home in Mexico City, and together they all traveled by train to Toluca, arriving in time for the morning conference session.

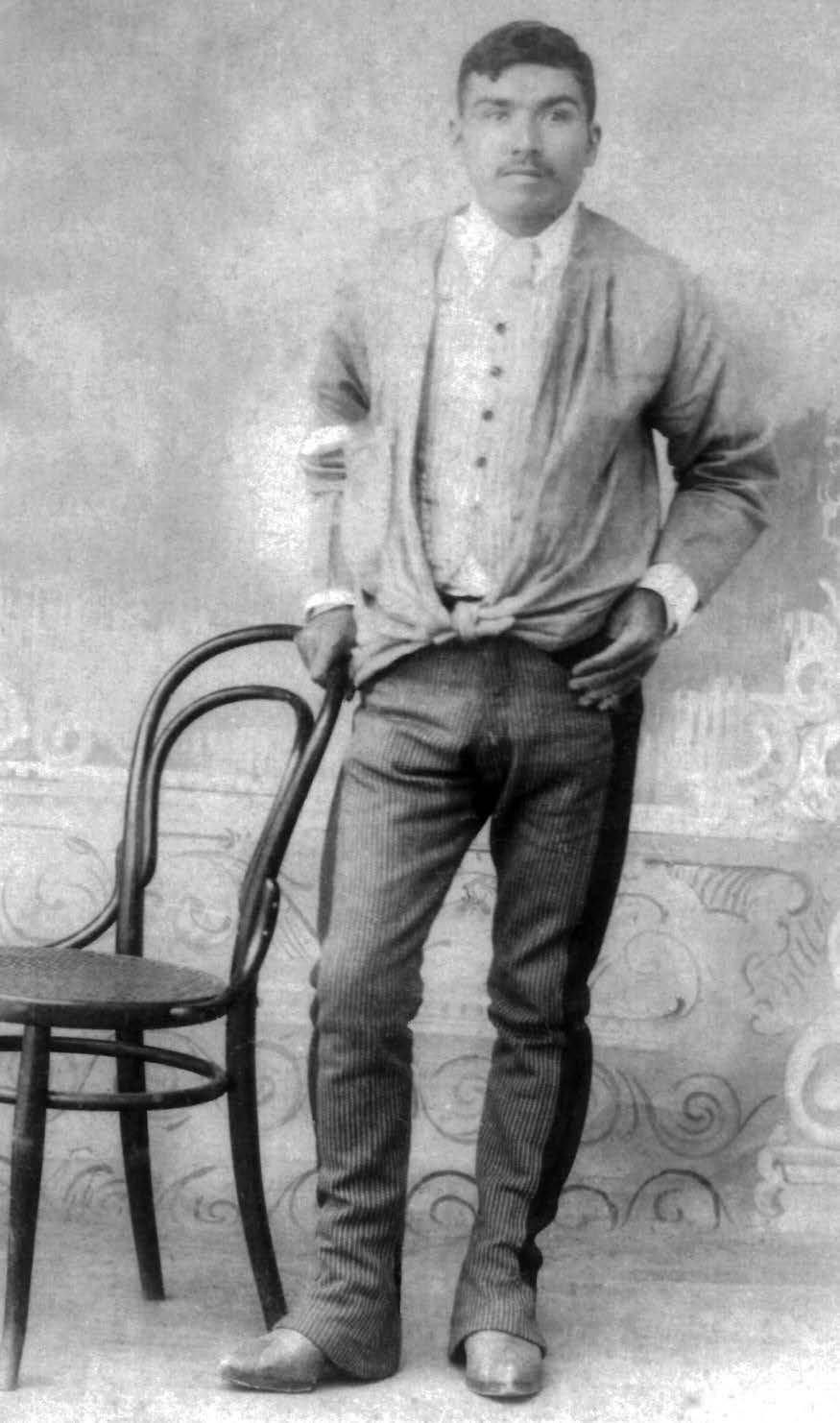

Isauro Monroy Mera (ca. 1900). First cousin to Rafael Monroy Mera, Isauro played a significant role in caring for the Monroys during difficult times. Although later alienated from the Church for many years, he remained a faithful Mormon. Scores of his descendants are found in the Church today, including Malena Villalobos Monroy, wife of Benjamín Parra Monroy, the Church’s first ethnic Mexican mission president. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Isauro Monroy Mera (ca. 1900). First cousin to Rafael Monroy Mera, Isauro played a significant role in caring for the Monroys during difficult times. Although later alienated from the Church for many years, he remained a faithful Mormon. Scores of his descendants are found in the Church today, including Malena Villalobos Monroy, wife of Benjamín Parra Monroy, the Church’s first ethnic Mexican mission president. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Unlike the conference in San Pedro Mártir, the Toluca experience was not a happy one. Locals threatened the missionaries with death and harassed members and investigators who came to attend. Rafael no doubt felt alarmed, and he was likely relieved to return quickly to his home in San Marcos.

Two weeks later, Pratt sent letters by trusted couriers to all the branch presidents (and to Monroy as well, who was the “senior male member” in San Marcos), informing them that the American embassy had issued evacuation orders for all Americans due to President Victoriano Huerta severing diplomatic relations with the United States.[44] Consistent with LDS President Joseph F. Smith’s admonition to follow the lead of the American embassy on this issue, Pratt, his family, and all the foreign missionaries were quickly packing and in the afternoon of 29 August would take the 8:15 p.m. train to the port of Veracruz. Pratt’s wife, Mary, had fallen ill from so much work and worry, and everyone in the mission home was in a panic to get ready to leave.

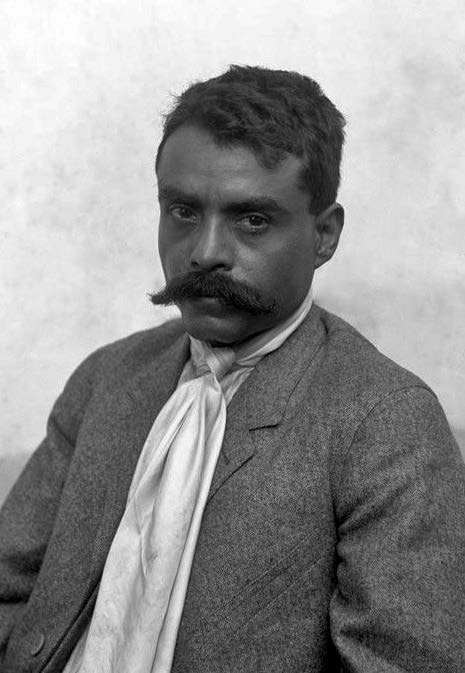

Emiliano Zapata (1914). A national hero in Mexico, he was famous for popularizing the phrases “Land or Liberty” and “It is better to die on your feet than live your whole life on your knees.” One of his militias, in alliance with Villista forces, took the Revolution to San Marcos, Hidalgo, where in 1915 they executed Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales, president and counselor in the San Marcos Branch presidency. Courtesy of Google Images.

Emiliano Zapata (1914). A national hero in Mexico, he was famous for popularizing the phrases “Land or Liberty” and “It is better to die on your feet than live your whole life on your knees.” One of his militias, in alliance with Villista forces, took the Revolution to San Marcos, Hidalgo, where in 1915 they executed Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales, president and counselor in the San Marcos Branch presidency. Courtesy of Google Images.

Given that Monroy did not receive his letter until the morning of the twenty-ninth, he had little time to do what he felt he must—travel to Mexico City to wish Pratt and the missionaries a safe journey and say goodbye. It was a fateful decision.

Monroy Becomes Branch President

How does a man of good will show up unexpectedly among panicked foreigners who have no time for chitchat and still be able to give them a proper Mexican despedida, a culturally appropriate farewell? The record gives no hint. However, it does disclose that Pratt, who was astonished that Monroy could make it to Mexico City so quickly, felt impressed to confer the Melchizedek priesthood upon him, ordain him an elder, and then set him apart as the president of the San Marcos Branch. Otherwise, the members there would have had no institutional leadership.

W. Ernest Young, then the mission secretary, saw it this way:

We were surprised by our dear Brother Rafael Monroy from San Marcos, Hidalgo, who came to tell us goodbye. He is a fine fellow and has the spirit of the gospel. He came in a good time. Although he had only a short experience in the Church, President Pratt thought it wise to ordain him an elder so that he could baptize and care for the small branch in San Marcos, Tula, Hidalgo. He accepted this call, and I gave him my hymnbook and other items to assist him.[45]

Agustín Haro to the Rescue

A freshly minted branch president seventy-nine days following his baptism, Rafael Monroy had his Cipriano de Valera Bible,[46] an 1886 translation of the Book of Mormon,[47] and a 1912 Mormon hymnbook containing the texts but no musical scores to twenty-three songs. But it did have cross-references to English hymnals that indicated which music was to accompany the verses.[48] He had a few missionary pamphlets, including Parley P. Pratt’s A Voice of Warning.[49] He had neither the Doctrine and Covenants nor the Pearl of Great Price, two of the faith’s four canonical works, both of which were yet to be translated into Spanish in any form.[50] He had no handbooks on Church administration or policies[51] and no lesson manuals for any auxiliary. He was on his own. And thus it was for two months.

As an evacuee in the United States, Rey Pratt issued copious correspondence to the branch presidents in Mexico. Some of the correspondence arrived at the intended destinations despite the war. It appears that in one letter Pratt asked Agustín Haro, president of the San Pedro Mártir Branch, to look after the members in San Marcos, perhaps suggesting that he involve the Ixtacalco Branch in some form of ad hoc administrative oversight. In any event, after consulting with Ángel Rosales, president of that branch, Haro penned a letter to Monroy, which arrived in San Marcos on 24 October 1913, advising him that he was sending Elder Jesús Flores from his branch and Francisco Rodríguez, a priest from the Ixtacalco Branch, to give Monroy a hand. He asked Monroy, and through him all the members in San Marcos, to receive them kindly. When the visitors arrived the following day, a Saturday, the letter of introduction they presented was from Ángel Rosales.[52]

The next day being Sunday, normal Church meetings would finally take place. They would be the first in San Marcos under the aegis of President Rafael Monroy.[53] However much he had tried to be a shepherd to his new flock of Mormons in the two months since his calling, holding formal Sunday meetings was not on his agenda, likely because he simply did not know what to do. Thus, on Sunday, 26 October 1913, the branch held the first formal meetings under Monroy’s presidency. He quickly learned how to do it, held meetings every Sunday thereafter, and faithfully kept the record books of those meetings, the Book of Acts, until his execution twenty-one months later on 17 July 1915.

In the meantime, Monroy had his ranch (El Godo) to attend to and field hands to supervise, his family’s store to help sustain, a wife and child to support and nurture, a widowed mother and two single sisters to be responsible for, and two nieces and one nephew living in his mother’s household, who, to some extent, depended on him. He was a busy man, and all this before the severe persecutions began.

Growing the Faith in San Marcos

Whether from Rey Pratt’s urgings or from Agustín Haro’s and Ángel Rosales’s independent leadership instincts and commitments, the branches in San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco extended consistent alternating assistance and support to the members in San Marcos. For example, merely two weeks after Agustín Haro’s visit to get sacrament meetings under way, President Ángel Rosales from Ixtacalco showed up with his priest Francisco Rodríguez to offer assistance and see how things had gone during the intervening time. The previous Sunday, President Monroy had held the meetings as instructed, and he was ready for more counsel and advice.[54]

Aside from the direct visits of Haro and Rosales, Rey Pratt continued to send numerous letters to Monroy; the two carried on a lively correspondence. Additionally, W. Ernest Young and Presidents Haro and Rosales also sent letters of advice and counsel, all intended to fortify Monroy with knowledge and confidence in his leadership and to give spiritual comfort to the San Marcos Saints, reminding them that it is not only for this life that humankind lives.[55] The concepts of eternity and we are not alone are powerful matters of the heart that help build institutionally solid and personally committed congregations.

By January 1914, twenty-three members and investigators were meeting in San Marcos, President Monroy was always talking up the Church with his friends and acquaintances, and Agustín Haro again made his presence felt, this time in company of Santiago Alquisira. The magnificent chronicler Guadalupe Monroy observed, “These missionaries encouraged the Saints and their faith increased.”

Haro and Rosales’s visits to San Marcos made them consider calling part-time local missionaries to take up the slack made evident when the full-time missionaries had been evacuated the previous August. Haro assigned his San Pedro Mártir Branch member Vicente Morales to begin missionary visits to San Marcos, usually every two weeks or so. Morales began in January 1914, arriving with various companions over the ensuing months, the first being Juan García, who had lived in the Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and—although a mature man of considerable experience—held only the priesthood office of teacher. Being a musician by profession, García enchanted the Monroy daughters.

Vicente Morales—a deacon who had long been committed to the gospel and ported a powerful testimony but was short on gospel finesse and knowledge and Spanish language ability, Spanish not being his mother tongue—was a representative of the “rustic part” of the Mormon social spectrum that was nevertheless being bonded into a community of Saints. During the next twelve months, his status changed from itinerant part-time missionary to Rafael Monroy’s ranch employee at El Godo. On 3 January 1915, he happily entered the Monroy family as the husband of Eulalia Mera Martínez, Jesusita’s niece, who had by then been living with the Monroys for at least two years.[56]

Through the visits of Vicente Morales and his companions, knowledge of the Monroy family and its work on behalf of the Church began to circulate in other areas, at least in San Pedro Mártir, Ixtacalco, and Toluca. There, people had become aware that the Monroys were relatively privileged people, which placed them in the customary position of being possible grantors to good causes. Around February 1914, the part-time missionary Francisco Rodríguez, from Ixtacalco, who had visited the Monroys on at least two occasions, sent a letter requesting help in settling some debts he had with Juan Páez, also a member, who was ill and needed assistance. Another member, Amado Pérez, a long-time faithful member, probably from Ixtacalco at the time, asked the Monroys to accept his only daughter into their family because the political situation had become precarious and he feared for her safety.[57] Civil order was breaking down, and not even the high broken-glass and barbed-wire-topped walls of well-to-do family compounds could continue to protect their residents. Other requests would come, some with an attitude of entitlement. It made no difference. The Monroys helped where they could with their money, time, and other resources.

Along the way, instructive spiritual blessings reinforced Rafael Monroy in his ecclesiastical and pastoral work in San Marcos. The branch president’s two-year-old daughter, María Concepción, affectionately called Conchita, fell morbidly ill with an undiagnosed, or at least undisclosed, disease that lasted forty days. Neighbors affirmed the illness to be God’s punishment for the family changing its religion. They added a prescription: Monroy should repent and pray to the Virgin of Guadalupe to heal his daughter.

Monroy was devastated. Although he may have consulted with the visiting part-time missionaries and perhaps even with Presidents Haro and Rosales, he ultimately wrote to Rey Pratt about his afflictions. In response, Pratt sent several letters of encouragement. (The civil war notwithstanding, the postal system still made deliveries almost everywhere in central Mexico.) In one of the letters, Pratt recommended that Monroy use his priesthood to anoint and bless his daughter and therefore heal her. This may have been the first time that Rafael had experienced an occasion to use his priesthood this way. Pratt gave him specific instructions. Monroy did as instructed, and the child was healed and lived thereafter to a relatively advanced age.[58] Heartened, San Marcos’s branch president redoubled his ecclesiastical and pastoral efforts.

Help from afar continued. Ángel Rosales was released as the Ixtacalco branch president, and his former priest, now elder, Francisco Rodríguez, who had been a recipient of the Monroys’ humanitarian aid, had become the new branch president there.[59] He wrote frequently to Rafael, giving him instructions, and now seemed to be in the forefront of sending part-time missionaries to San Marcos. Thus, on 27 March 1914, he sent Antonio Páez with Vicente Morales to get the Sunday School set up; in the evening, they held a missionary meeting.

Whether for this visit or other reasons, three days later another baptismal service was held in San Marcos in which Jesusita’s daughter, Natalia, and other family members or friends were baptized. Aside from Natalia, these included Daniel Montoya, Taurina Pérez, Juana Mera, Isauro Monroy, and Alberto Tovar. Now, with increased confidence and experience, branch president Rafael Monroy performed the baptisms and confirmations himself.[60]

A week later, Agustín Haro, with companion Teodoro Juárez, arrived and established the pattern of holding Sunday School in the mornings and cultos, sacrament meetings, in the afternoons or evenings.[61] Whatever conversations the San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco leaders were having with each other and whatever the source of their administrative oversight—whether from competition, autochthonous desires to help, President Pratt’s letters, or perhaps district leaders President Pratt was trying to put in place at the time—the new San Marcos Branch, its members, and its branch president were amply being looked after.

Having received much help from others, the San Marcos Saints were now in a position to reciprocate. It happened this way: Around the latter part of April 1914, some of the male members in the San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco branches were running the risk of being conscripted into the Twenty-Ninth Battalion of the federal army. President Pratt had counseled members throughout Mexico to remain neutral and not take sides in the war. The San Pedro and Ixtacalco men tried to follow his counsel by fleeing to other parts of central Mexico. However, by so doing they left their home branches bereft of a priesthood base sufficient even to hold meetings. In any event, the men were afraid to be at gatherings of the Saints lest federal troops appear and conscript them on the spot.[62]

President Francisco Rodríguez of Ixtacalco was one who fled. This patriarch of a large family was now left without work to support his loved ones, even to obtain their basic food with which to sustain life. He pled with the San Marcos Saints to impart a few funds to help them. They responded. Then, Trinidad Haro, son of branch president Agustín Haro in San Pedro Mártir, bolted to San Marcos looking for refuge. He found it with Rafael Monroy at El Godo, along with a remunerative job as a ranch hand.[63] Others followed. As the war continued to unfold, San Marcos became, for a while, a place of refuge for a number of Mormons throughout central Mexico, whom the members embraced as fellow Saints.

Rafael had a large project in mind that was perhaps partially underway to aid destitute members who were arriving in San Marcos seeking refuge from the war. The Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and Sonora inspired this project. Through lengthy conversations with Juan García, who had lived in those colonies, Monroy became aware of how the Anglo American Mormons there “helped one another . . . and how all worked together, women and children as well as the men” to advance their communal cause and prospects for survival.[64] Monroy may have seen something like the Mexican ejido (communal land) system, which had regained much ideological currency at the time, in these Mormon practices.[65] He raised the matter by letter with President Pratt, who in mid-December 1914 responded enthusiastically to the idea but also laid out a dose of realism on practical problems within the local Mexican culture. At the same time, he extended his counsel on how to work around cultural impediments to such a project. Pratt emphasized the idea of a formal contract. Emboldened, Monroy went to work to secure the lands.[66] In six months, he would be dead, so the project never really got off the ground.

That reality notwithstanding, refugees kept arriving. For example, Casimiro Gutiérrez, along with his wife and numerous children, showed up when no available housing existed in San Marcos, so the McVeys got them settled in San Miguel, where they helped Casimiro start a business. Gabriel Rosales; his wife, Modesto Gutiérrez; and their son; and President Francisco Rodríguez; his wife, Anacleto; and their sixteen-year-old ward, Ana Páez, all from the Ixtacalco branch, were among those settled with the members in San Marcos and were helped to find ranch and domestic employment.[67] Rosales later joined the Zapatistas.[68]

In June 1914, the San Marcos members celebrated the first anniversary of the first baptisms in their community. As a sign of development and emerging maturity, some of the converts routinely took part in the services, testimony meetings were lively, and the Church gave evidence of becoming institutionalized in the village.[69] This was a good prognosis given that Pratt’s only influence in the mission was through his weekly letters, which the San Marcos Branch routinely received, although Pratt apparently did not receive any responses.[70]

Despite the war and even the Carrancista and Villista/

The war, the newness in the gospel, and the resettlement problems all posed challenges. It was certainly true that the period 1913–15 was difficult for the San Marcos Mormons. However, one central fact remained. The members were studiously engaged in internalizing the Mormon way, which included not only Mormon doctrine, however esoteric, but also a social gospel that embraced member refugees and extended them humanitarian aid. It was a time of growth—spiritual, temporal, experiential—increasingly on their own.

Notes

[1] For a specific discussion, see LaMond Tullis, “La Reapertura de la Misión Mexicana en 1901,” 15 November 2012, http://

[2] The interregnum of twelve years is discussed in LaMond Tullis, “Los Colonizadores Mormones en Chihuahua y Sonora,” 26 September 2012, 14–15, http://

[3] During January 1913, missionary W. Ernest Young twice mentions being in San Marcos. On the eleventh, he stayed with LDS member Jesús Sánchez. On the twenty-eighth, he visited the Monroys “and other friends.” He mentions Sánchez as “our only member.” On this trip, he, with local missionary Eliseo Jiménez, went to San Sebastian to visit Lionel Yáñez, son of José María Yáñez and grandson of Desideria Quintanar de Yañez, the first woman baptized in central Mexico. For the account of Desideria, see LaMond Tullis, “La Primera Mujer Bautizada en México: Desideria Quintanar de Yánez (1814–1893),” 7 December 2012, http://

[4] “Martirio en México,” 4. W. Ernest Young, in the reflective appendix of his diary (669), says: “During the first years of the Mexican Mission, 1879 to 1889, converts were baptized in San Marcos, a town forty-five miles north of Mexico City. In the year 1881, Elder August Wilcken baptized Jesús Sánchez. It was he that still lived in San Marcos in 1913. He had been visited at times during the intervening years, but proselyting had not been carried there for years until 1913. We had heard of his illness, and on March 29 Elder Willard Huish and I arrived in San Marcos to see him.” For a discussion of the mission of Apostle Moses Thatcher, see LaMond Tullis, “La Misión del Apóstol Moses Thatcher a la Ciudad de México en 1879,” 12 October 2012, http://

[5] Young, Diary, 86–87; Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 1.

[6] “Jesús Sánchez was a faithful member of the Church from his baptism 5 July 1881 until his death in San Marcos 29 March 1913. Despite the first missionaries who baptized him having left Mexico, he remained faithful. New missionaries visited him whenever possible even before contacting the Monroy family. Thus, after his death the formal preaching of the Gospel to the Monroy family began.” “Martirio en México,” 4.

[7] I have reconstructed this conversation from Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 1.

[8] Some accounts state that Young and Sirrine were the first to contact the Monroys. Guadalupe Monroy, one of the principals, states that a pair of missionaries—not these two—had approached them two months earlier. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 1.

[9] Tullis, “La Primera Mujer Bautizada en México”; Christensen, “Solitary Saint in Mexico.” As for Young’s and Sirrene’s tour, see Young, Diary, 81–82.

[10] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 3. Guadalupe Monroy, who never found a marriage partner, had hoped to marry a missionary or at least fantasized as much. Everyone was urging her simply to take a partner in order to have children, but she could not bring herself to marry outside the Church, and no young, available Mexican Mormon appealed to her. Among the normal, nearly imponderable issues of attraction, social-class differences would have weighed on her. In the waning years of her life, she reminisced: “My youth unfolded. The age for selecting a husband disappeared as flocks of birds fleeing the coming winter in search of a better climate. I ceased trying with the missionaries. All the young Americans were steeped in a racism that forbade their liking Mexican girls” (Mi juventud se deslizó. La edad para elegir un esposo voló como las aves vuelan cuando el invierno viene, y se van en bandadas a buscar un clima mejor. No traté más con los misioneros. Todos ellos jóvenes Americanos, que el racismo los tenía bien vedados de simpatizar con las mexicanas.) “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 110.

[11] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 1.

[12] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 1–2.

[13] Natalia was married in May 1912 to the American R. V. McVey, who was in San Marcos as a skilled worker for the American-owned Tolteca cement-manufacturing plant, which symbolized the extent to which the Monroys had taken up with the Americans.

[14] Desideria Quintanar de Yañez, baptized 22 April 1880, may not have been the first female baptized in all of Mexico. The missionary journal of Louis Garff, companion of Melitón Trejo on their mission to Sonora, records the following: “Sunday, May 20, 1877, I baptized José Epifanio and Jesús. On Thursday the 24th of May I baptized José Severo Rodríguez, María la Cruz Pasos, and José Vicente Parra, in a small settlement a few leagues from Hermosillo city in the State of Sonora. These five baptisms were the first in all of Mexico in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.”

[15] Mormon expatriate colonists in the northern states of Chihuahua and Sonora first felt the scimitar of the Revolution and were driven from their lands back into the United States. This book deals with the Saints in central Mexico. However, interested readers may find this chapter in my book to be useful: “Revolution, Exodus, Chaos,” in Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 87–108.

[16] Some basic works on the Mexican Revolution are noted in endnote 3 of chapter 1.

[17] See Horacio Labastida, Belisario Domínguez y el estado criminal, 1913–1914 (Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores, 2002).

[18] A relevant and nearly contemporaneous view is Luis Manuel Rojas, La culpa de Henry Lane Wilson en el Gran Desastre de México (México: Compañía Editora “La Verdad,” ca. 1928). Wilson’s apologia over the firestorm his service in Mexico created is his Diplomatic Episodes in Mexico, Belgium and Chile (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927). Henry Lane Wilson’s legacy appears to have outlived his tenure as ambassador to Mexico, which ended with his dismissal on 17 July 1913. The outrage in San Marcos may have been an afterglow from the legacy of Wilson but may have also derived from a rumored US invasion of Veracruz. However many Mexicans lamented the assassination of Francisco Madero (for example, as did the old San Marcos Mormon Jesús Sánchez) and the involvement of Ambassador Wilson in that sordid act, the US position under newly elected US president Woodrow Wilson was decidedly anti–Victoriano Huerta. He cashiered Wilson and appointed a new ambassador, John Lind, a former governor of Minnesota and a member of the US House of Representatives, to whom he gave careful anti-Huerta instructions. Nevertheless, “Lind spoke no Spanish and carried strong Protestant, anti-Catholic prejudices into the overwhelmingly Catholic Mexico. . . . Lind was empowered to negotiate with Mexican officials. [US president] Wilson had instructed Lind to press Huerta’s government for ‘an immediate cessation of fighting throughout Mexico’, an ‘early and free election’ in which all parties could participate, a promise from Huerta not to be a candidate, and an agreement by all parties to respect the results of the election. In return, the United States promised to recognize the newly elected government. The Huerta regime met with Lind but refused to accede to Wilson’s demands.” Mark E. Benbow, “All the Brains I Can Borrow: Woodrow Wilson and Intelligence Gathering in Mexico, 1913–1915,” Studies in Intelligence: Journal of the American Intelligence Professional 51, no. 4 (2007): 1–12. The venomous relations between Mexican president Victoriano Huerta and US president Woodrow Wilson’s new personal representative to Mexico, John Lind, are captured in John Lind, Mexico in Transition: The Diplomatic Papers of John Lind, 1913–1931, comp. Dan Elasky (Bethesda, MD: LexisNexis, 2005), microfilm reel 1.

[19] The mission even developed a set of precautionary guidelines for missionary conduct during this time. Grover, “Execution in Mexico,” 13; Young, Diary, 92.

[20] Young, Diary, 90–91; Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 2; “Martirio en México,” 5.

[21] Young, Diary, 90–91.

[22] Frank McLynn, Villa and Zapata: A History of the Mexican Revolution (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2000).

[23] Young, Diary, 90–91.

[24] Young, Diary, 91. The missionaries never returned thereafter to the Sánchez home. Thus, “with Señor Sánchez’s death the missionaries never returned to this brother’s house because his family had no interest and they rejected the true religion that their father had professed.” Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 2.

[25] Sally Johnson Odekirk, “Mexico Unfurled: From Struggle to Strength,” Ensign, January 2014, 38.

[26] María Guadalupe Monroy Mera reflected on this phenomenon in the appendix of her narrative about San Marcos, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 108. Apparently, it was a topic of continuing conversation down through the decades. Isaías Juárez, the district president during and following the troubling times that the revolution began, commented about how the first Mormons in San Pedro Mártir also had been the first Protestants.

[27] According to María Guadalupe Monroy, the issue was the impressment of Cándido Robles and Regino Reyes into the Zapatista militia. Even by this time, the Monroys had negative views about the insurgent Zapatistas. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4. However, several Mormons from Morelos, and those who would become Mormons, were inclined toward the Zapatistas, including Ambrosio de Aquino, who, before joining the Church, became a major in the Zapatista militia. Armando Ceballos and Dina DeHoyos de Ceballos, “Nefi De Aquino Gutiérrez: Heredero de una Historia de Fe en Santiago Xalitzintla, Puebla” (unpublished typescript, ca. 2014); this document is based on an oral history recorded by Anselmo Mata and Luz Mata on 11 August 2013 and submitted to the Church History Library. The more likely event is that Mexican federal troops had picked up the men, along with other Mormons, and accused them of being Zapatistas. Pratt was trying to get the federal forces to release the men. Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, 98–100.

[28] “We were surprised to see the missionaries eating the really humble food that the members in San Pedro had given them.” (Nos quedamos sorprendidos, de haber visto comer a los misioneros las comidas tan humildes que les habían dado los hermanos de San Pedro.) Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4.

[29] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4.

[30] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4.

[31] The Monroys received the letter on 7 June 1913 and learned that Pratt would be in San Marcos on the tenth. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4. Pratt would have sent his letter by the latter part of May, just a few days following the conference. His assistant, W. Ernest Young, must have given him a glowing report about the Monroys in San Marcos.

[32] Young, Diary, 99. The Monroys’ request was not unusual. Immediately following the early Mormons’ expulsion from Nauvoo and during their trek across the plains to the Great Basin, they performed vicarious work in the “natural temples” along the way (streams and brooks and secluded groves). The Saints also did these ordinances at Winter Quarters (Nebraska) and in the Council House in Salt Lake City until they completed the Endowment House there in 1855–56. After this time, they confined vicarious work to the Endowment House until the dedication of the St. George Utah Temple in 1877. Thus, the natural inclination the Monroys had was not out of line with LDS temple practices of the time period two or three generations before their own baptisms in 1913. Richard E. Bennett, “‘The Upper Room’: Latter-day Saint Temple Work during the Exodus and in Early Salt Lake Valley, 1846–1854” (presidential address, Mormon History Association conference, San Antonio, Texas, 7 June 2014). See also Bennett, “‘Which Is the Wisest Course?’ The Transformation in Mormon Temple Consciousness, 1870–1898,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2013): 5–43; and Bennett, “‘Line upon Line, Precept upon Precept’: Reflections on the 1877 Commencement of the Performance of Endowments and Sealings of the Dead,” BYU Studies 44, no. 3 (2005): 39–76.

[33] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4–5. See also, Young, Diary, 106–7; and “Martirio en México,” 4.

[34] Sánchez was among several that W. Ernest Young mentions as being baptized in the vicinity of San Marcos during 1879–81.

[35] As an example, as the family was moving into San Marcos, one politically well-placed family member secured a teaching position for Natalia in the village of Llano, a teaching position for Jovita in San Marcos, and a position of police commander in Tula for Rafael. “Biografía de Mamá Jesusita Mera Narrada por Minerva Montoya Monroy” (unpublished typescript, five pages, copy provided by Hugo Montoya Monroy, 1 March 2014), 2–3.

[36] Richard Thomas, in his 3 September 2014 critique of an earlier draft of this book, transcribed his personal audio recording of the following comment from President Gordon B. Hinckley, which he made to new LDS mission presidents on 21 June 2005: “Now I wish to say a word concerning the kind of people with whom our missionaries work. We’ve never been able to get very far with the highly educated, the wealthy, those whose manner is arrogant or self-centered. Over the years, our message has appealed to those in relatively humble circumstances. The great numbers harvested in England and subsequently in Europe in the early days of the Church were generally people of very modest means. The Perpetual Immigration Fund was established to help them immigrate to Zion when they were powerless to help themselves. But, while they were poor in the goods of the world, they were for the most part people of integrity. They were law-abiding and people of good intellect. Their posterity has added to the luster of the lives of their forbearers through education. They become people of great capacity, of great faith, of great activity and leadership in the Church.”

[37] Young, Diary, 100.

[38] Young, Diary, 101.

[39] “Biografía de Mamá Jesusita Mera Narrada por Minerva Montoya Monroy,” 3.

[40] “With their novenas and rosaries [recitation of prayers], which they did daily so that the Monroy family would return to being Catholic.” Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio”, 5. In the Roman Catholic Church, novenas refers to a recitation of prayers for nine consecutive days for a specific purpose and to induce a sought-after end.

[41] During Pratt’s visit to the Monroys, one of Rafael’s paternal aunts—who loved him, at least by her previous words and actions—came to the Monroy home for a visit, arriving during one of the “cottage meetings” that Pratt was conducting. Offended, she quickly withdrew and alerted other family members regarding the “cult” happenings in the Monroy home. The extended family thereafter pulled away. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 6.

[42] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 5.

[43] Young, Diary, 106.

[44] Francisco Ramírez was Pratt’s courier to San Marcos. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 6. The war seemed to take international observers by surprise, even the Buffalo Historical Society in New York, which refocused its entire annual volume in 1914 to address the Mexican Revolution. Within the volume’s first chapter, the machinations of Mexico’s Victoriano Huerta and the US response are chronicled. See Frank H. Severance, “The Peace Conference at Niagara Falls in 1914,” in Buffalo Historical Society Publications, vol. 18, ed. Frank H. Severance (Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Historical Society, 1914), 3–75.

[45] Young, Diary, 110. Guadalupe Monroy records the event as her brother Rafael related it to her. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 6.

[46] Rafael Monroy would have owned either the 1865 or the 1909 version of the Cipriano de Valera Spanish version of the Bible, frequently also known as the Reina-Valera translation, which was prepared for the then-blossoming Protestant movements in Spanish-speaking countries and widely regarded as the Spanish equivalent of the King James Version in English. An informative discussion that places Valera’s enormous work in historical context is A. Gordon Kinder, “Religious Literature as an Offensive Weapon: Cipriano de Valera’s Part in England’s War with Spain,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 14, no. 2 (Summer 1988): 223–35. Some indication of Valera’s far-reaching impact are the over thirty-five thousand entries retrievable from the Internet.

[47] The 1886 translation of the Book of Mormon, prepared by Melitón González Trejo and James Z. Stewart, is the first complete published Spanish edition. LaMond Tullis, “El Libro de Mormón en Español: La Primera Traducción y Cómo Llegó a México,” 19 July 2012, http://

[48] At the time, Mexico was the only Spanish-speaking country where missionaries were working, and the effort to create rough-text Spanish hymnals took place entirely there. In 1907, missionaries had produced a twelve-hymn forerunner to the referenced 1912 version. An extensive and heavily documented treatise on this subject is John-Charles Duffy and Hugo Olaiz, “Correlated Praise: The Development of the Spanish Hymnal,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 2 (Summer 2002): 89–113. Analogously, US Mormons had produced many “frontier poets” who wrote their poetry intending it to be set to music scores of established hymns or songs. An example is Mary Brown Henry. LaMond Tullis, A Search for Place: Eight Generations of Henrys and the Settlement of Utah’s Uintah Basin (Spring City, UT: Piñon Hills Publishing, 2010), 212–13.

[49] Sixty-eight English editions have been published of Parley P. Pratt, A Voice of Warning and Instruction to All People; or, an Introduction to the Faith and Doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1874). The first Spanish edition was prepared and published in Mexico in 1880. Tullis, “La misión del Apóstol Moses Thatcher,” 8, 14n20.

[50] Portions of the Doctrine and Covenants were published in Spanish in the early 1930s as Revelación de los Últimos Días. The entire Doctrine and Covenants was not published in Spanish until 1948, the same year that the Pearl of Great Price was also published. Thus, not until the mid-twentieth century did the Church’s entire canonical works become available to Spanish-speaking members. See Eduardo Balderas, “How the Scriptures Came to Be Translated into Spanish,” Ensign, September 1972, 29.

[51] By 1939, English speakers had access to John A. Widstoe’s authorized work that was revised in 1954 and published as Priesthood and Church Government in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954). It was heavily abridged in 1956 and published in pamphlet form as “Melchizedek Priesthood Handbook.” Understandably, as late as 1956, there still were no manuals in Spanish dealing with priesthood administration, and the Doctrine and Covenants had been available only since 1948. In desperation, in preparing leadership-training modules for the Saints in Central America in 1956, LaMond Tullis, then serving as first counselor to Edgar L. Wagner in the Central American Mission presidency, unskillfully translated the Melchizedek Priesthood Handbook, printed a hundred copies on the office mimeograph, and circulated them to priesthood leaders throughout the mission.

[52] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 6.

[53] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 6–7.

[54] The Sunday visit took place on 9 November 1913. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7.

[55] “All of these letters dealt solely with the beautiful knowledge of the Gospel that we had accepted and our hope in a life hereafter.” (Todas estas cartas se relacionaban únicamente al hermoso conocimiento del Evangelio que habíamos aceptado y de la esperanza en la vida venidera.) Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7.

[56] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7. See also Grover, “Execution in Mexico,” 16.

[57] The Pérez name figures ubiquitously in the Monroy family connections. The records do not disclose whether Amado Pérez was part of the extended family. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 8.

[58] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 8–9.

[59] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 8–9. It is unclear how these administrative tasks were undertaken and how the administrative structure was working in Mexico at the time. Pratt may have been doing all this by letter from the United States, relying on trusted people such as Isaías Juárez, who later would become the district president, to carry out the tasks under Pratt’s direction.

[60] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 10.

[61] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 9.

[62] The prospect of conscription (forced enlistment) in the federal army or any of the militias opposing it was terrifying. For most people the actual experience was traumatic. Women were also conscripted as fighting soldiers (and many volunteered, especially for the Zapatista militias). See Francisco Martínez Hoyos, “El Vientre de los Ejercitos,” in Breve Historia de la Revolución Mexicana (Madrid: Ediciones Nowtilus, S. L., 2015). Rural women in the Yucatán organized themselves into bands to forcefully resist the conscription of their men. See Allen Wells and Gilbert M. Joseph, Elite Politics and Rural Insurgency in Yucatán, 1876–1915 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 242.

[63] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 10. Following advice to stay neutral at such times certainly points out the unintended real-world consequences. At this time, except perhaps in the state of Morelos, most Church members appear to have been in favor of the government (the Carrancistas) in whatever permutation rather than preferring the Zapatistas or Villistas, whether in coalition with each other at any given moment or not. An uncharitable observation would be that the presidents of Ixtacalco and San Pedro Mártir saw Rafael Monroy less as a man who had a slow learning curve and who needed considerable help than one who could perhaps offer a place of refuge to them, their families, and perhaps other members if they struck up a relationship with him. However, there is no direct evidence to support this position. Later, Monroy would try to set up a colonization effort for such people, following the earlier pattern that Anglo members had undertaken in the states of Chihuahua and Sonora.

[64] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 12–14. For a treatise on what Monroy was trying to replicate, see LaMond Tullis, “Los Colonizadores Mormones en Chihuahua y Sonora.”

[65] The enduring strength of this ideology is reviewed by Nora Haenn, “The Changing and Enduring Ejido: A State and Regional Examination of Mexico’s Land Tenure Counter-Reforms,” Land Use Policy 23 (2006): 136–46.

[66] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 14.

[67] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 13–14.

[68] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 24.

[69] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 11.

[70] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 11.

[71] Grover, “Executions in Mexico,” 14.

[72] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 12.