Institutionalizing the Church in San Marcos and Environs

F. LaMond Tullis, "Institutionalizing the Church in San Marcos and Environs," in Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 85–128.

In San Marcos, the Church’s institutionalization took time. When the Church is institutionalized in any area, its doctrines, mission, policies, vision, action guidelines, codes of conduct, central values, and eschatology associated with the restoration of the gospel become integrated into the culture of its leaders and members and sustained through time by its organizational structure. Even under the best of conditions, institutionalization is a lengthy temporal and spiritual process for a new faith.[1] The social, political, and economic upheavals affecting the early Church in Kirtland, Ohio; Nauvoo, Illinois; and Utah Territory from 1833 to around 1915 certainly illustrate the conundrum.

During the Church’s early years in San Marcos, optimal conditions for institutionalization did not exist. The cultural changes required of a people of God were slow in coming to some of its leaders and members. The drag of traditional Mexican culture was at times robust and resilient. Unsettled political conditions, including the civil war, thwarted necessary attention from Church headquarters. Leaders’ self-education in gospel and Church governance matters was thwarted by a lack of Church literature, including a complete Spanish translation of the Doctrine and Covenants (not available until 1948)[2]. In the early days until 1919, when they dedicated their first self-built chapel, the San Marcos members had no adequate facilities in which to meet. Aside from that, people’s testimonies, no matter how deeply embedded in the sentiments of their souls, could not replace the members’ need to have more than just basic knowledge about their new faith. The Saints needed taproot information about what they should be doing to draw nearer to God within the fabric of a gospel culture that incorporated the faith’s doctrines of salvation.

Despite all these impediments, a century later in 2015, San Marcos has two vibrantly functioning LDS wards attached to the Tula Mexico Stake.[3] Two more wards are in the outskirts of the municipal seat of Tula,[4] and there is one ward in nearby San Miguel,[5] plus an additional four wards and two branches in the larger municipality.[6]

Along the way toward developing an institutionalized church in San Marcos, members have made impressive accomplishments. Early on, they launched an innovative chapel-building program to meet their worship needs. They pioneered a member-sponsored educational endeavor that became the prototype for the Church’s 1964–2013 educational system in Mexico.[7] They successfully resisted the overtures of Mormon dissidents and schismatics such as Margarito Bautista and his New Jerusalem, and Abel Páez and his Third Convention.[8] They have produced a large number of local and regional Church leaders. Its members have been financial contributors; temple attenders; missionaries; teachers; mission presidents; temple presidents; and local, regional, and general authorities. Some of its families have accomplished a difficult-to-replicate conservation of knowledge of their history.[9]

In the here and now, no community of Saints can perhaps ever completely embrace a gospel culture (that of the City of Enoch and the Nephite period following Christ’s visit to the Americas, as Mormons note, being exceptions). However, the members in San Marcos have moved a considerable distance in the transition toward such a culture. It has not been easy.

The turbulent journey the Mormons traveled from 1912 when the Church cemented its roots in San Marcos to as late as the mid-1970s was stormy from time to time. A number of factors threatened institutionalization. First among them, of course, was the civil war and its wholesale assault on normal life that also occasioned the martyrdom of two members of the San Marcos Branch presidency and produced an uncertain outcome in leadership succession. Further complicating everything was the inexperience of the faith’s leaders who were isolated from mission president Rey L. Pratt by nearly two thousand miles of inhospitable terrain and hampered by an only partially working mail system. Leaders from San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco helped fill the void, but they, too, were unseasoned and very isolated. They nevertheless pursued every avenue open to them to help the Saints in San Marcos as well as other LDS congregations in Hidalgo.

Aside from these structural issues, the personal failings of some of San Marcos’s successor leaders not only sapped their spiritual vitality but, for a time, also set a poor example for instilling a gospel culture among the Saints. Afterward, the lure of schismatic breakaway movements caused pause, something that had to be resolved to cement the Saints’ faith in their convictions. Of course, the development of faith and conviction is something that has to happen in every new generation. In San Marcos, although there were hiccups along the way, this institutionalization began to transpire as well.

To illustrate the transformative process and point out the enormous chasms the San Marcos Saints have bridged (and perhaps even to suggest some of the necessary conditions for institutionalizing the Church among a new people, including progressive efforts to adopt a gospel culture), we look at the following: leadership succession, education, cultural change, membership core, and institutional support. We take up leadership succession in this chapter, and the balance in chapter 7.

Leadership Succession

By example in word and deed, personally ministering to the Saints in their needs, Church leaders strive to teach Christ’s expectations not only about faith but also about behavioral and other standards—social conduct, ethics, and an understanding of what it means to be informed by a gospel culture. Most of the time, good examples reign supreme over the other kind. However, sometimes the exceptions are spectacular.

Ordinarily, at the local level a branch presidency or ward bishopric dissolves when its president or bishop is unable to continue serving. Ecclesiastical authorities (e.g., stake presidents, mission presidents, Seventies, Area Presidents, or Apostles, depending on the level of the vacancy) take counsel and decide on a replacement. Thus, periodically, a nearly seamless transition occurs as qualified leaders take lay-leadership positions in a church that, at local and regional levels, has no paid clergy. Usually, such people have received training through a number of years to be able to step in whenever a need arises. Sometimes there are disappointments—immorality, lack of dedication, insufficient knowledge, politicization of a religious office, embezzlement—and on occasion, sooner-than-expected releases occur. However, overall, leadership transitions are accepted and the Church moves on.

In San Marcos, the need for a new branch president arrived when Rafael Monroy was executed. As no ecclesiastical authority was around to effect a replacement,[10] the succession, if there was to be one, would require someone’s impromptu decision. Who was that someone?

Casimiro Gutiérrez

Casimiro Gutiérrez stepped forward. After Rafael’s death, Gutiérrez was the only one in San Marcos who held the Melchizedek Priesthood. During the civil war, he and his family had arrived from Toluca as member refugees. Rafael took note of his commitment to the Church and ordained him an elder, later perhaps inviting him to serve as second counselor in his presidency.

Casimiro conducted Rafael and Vicente Morales’s funeral. Barely a week later, as soon as it was safe, he conducted Sunday School and sacrament services for the Saints—on a Wednesday! For many months thereafter, he faithfully shepherded these weekly meetings in the Monroy home. He tried to reconstitute the presidency by bringing on as assistants Gabriel Rosales, a teacher, and Isauro Monroy, a deacon.[11]

It appears that as soon as Rey Pratt became informed of events, he ratified Casimiro’s leadership status even though no one was around who could set him apart as the new branch president. In due course, Pratt began to write letters to Casimiro not only giving him counsel and advice but also reproving him for some of his actions that someone had reported.[12]

The Miscues

What were Casimiro’s actions, omissions, and miscues? Whatever they were, Church members perceived them from the vantage of the social and psychological fright that had just savaged their lives. That, together with the absence of their beloved Rey Pratt, made it difficult for the new leader to achieve an accorded authority that would legitimize his leadership.[13] As some opined, he was well intentioned, but his actions undermined him.

Casimiro carried a lot of hurtful cultural baggage—authoritarianism, caudillo mentality (a way of viewing leadership as controlling people through vigilance and patronage rather than leading with trust and fraternal love), reluctance to accept counsel, propagation of female subservience, and consumption of alcohol as a stress reliever. All these were attitudes and behaviors embedded in traditional Mexican culture of the time but quite antithetical to the principles of a hoped-for gospel ethos.

Casimiro’s best intentions and efforts notwithstanding, in quick order he began to offend people. Members in San Miguel were among the first to push back by ceasing their attendance at Church meetings. Others felt shoved away. Some of the younger members, including Bernabé Parra, began to admonish a few of the older ones about their drunkenness and adulteries, which further created a generational divide. Sensitivities to class divisions within the membership arose, and gossiping became ferocious. Those with weak testimonies and those who became severely offended simply stopped attending church.

All these problems aside, week after week Casimiro continued to conduct Church meetings for all who would come. Many branch members gave talks and taught lessons, including the unordained Bernabé Parra, who appeared to be working hard to calm people down, urging them to reconsider the larger issues that had brought them together.[14]

By mid-year 1916, Ángel Rosales from Ixtacalco had returned to San Marcos, as he would yet do several times, to preside over the meetings.[15] Perhaps he was trying to take stock of the seriousness of the leadership turmoil. It is likely that he made a report to mission president Rey L. Pratt.

Breakdown

Casimiro’s personal disappointment about these events joined his cultural baggage to foster domestic issues with his wife and children, which again turned him to alcohol and infidelity. Yet, even as an addicted alcoholic and a breaker of the law of chastity, he continued as branch president, holding meetings and carrying on with his duties. However, by early 1917, his dissonance became greater than his will, and even he ceased attending church. Oddly, rather than Gabriel Rosales or Isauro Monroy, the president’s “assistants,” it was Daniel Montoya, a teacher, who conducted some of the services in Casimiro’s absence. The branch presidency, if there was a branch presidency, had evaporated. Apparently, the members simply gathered and on a weekly basis voted on someone to lead their services. One time, they even selected the newly ordained deacon Bernabé Parra.[16]

For four months, the nominal president of the San Marcos Branch was absent from Church services. Somehow, others carried on, focusing principally on Sunday School, sacrament meeting, and a branch social or two. Upon returning to Church the first Sunday in May of 1917, Casimiro took the opportunity at fast and testimony meeting to complain that someone had been writing to President Pratt giving false information about him, which had occasioned his withdrawing from the church meetings. Characteristically, caudillos fail to accept personal accountability for at least some of their problems. Leadership maturity would yet be some time in coming to the Church in San Marcos. The Church’s institutionalization was somewhere in the future.

Two months later, Casimiro decided to pick up his role as branch president again by initiating a memorial service (culto fúnebre) for Rafael and Vicente.[17] Astonishingly by today’s standards, he was able to do this simply because the members had forgiven him his sins. However, his wife had not. She took her turn at the subsequent fast and testimony meeting to denounce her husband.[18]

All this was too much for everyone, certainly for President Rey L. Pratt. In a move that localized district oversight for San Marcos in the Church’s leadership at Ixtacalco, by letter Pratt instructed Dimas Jiménez of that branch, whom he personally had ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood, to “renovate” the San Marcos Branch presidency.[19] Along with others from Ixtacalco, Jiménez appeared at the Sunday services of 13 August 1917 with Pratt’s letter in hand, which instructed him to release Casimiro, which he did.

Some people live an exemplary life when life is easy, some when it is hard. Casimiro Gutiérrez, a good man in many ways, fell in between. The cultural circumstances of his life, the structural conditions under which he lived, and the turbulence of a civil war imposed burdens beyond his ability to cope. All his efforts notwithstanding, and accepting at face value the goodness of his intentions, he was unable to adopt some of the essential elements of the gospel culture he aspired to embrace. Someone needed to make a new effort to reclaim the disenchanted Saints and bring them back to the community of the faithful.

Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez

Pratt’s letter instructed Dimas Jiménez to advance the youthful and unmarried Bernabé Parra from deacon to elder in the priesthood and to set him apart as the new branch president. In his acceptance remarks, Parra expressed appreciation for the much good that Casimiro had accomplished while also lamenting his periodic withdrawals from the Church.

This top-down leadership change was all new to the Saints in San Marcos. They appropriately wondered if Bernabé Parra would be any more successful than Casimiro as branch president, nevertheless acknowledging the comforting role Casimiro had played in many of their lives as he strove to find and do the will of the Lord for them. In varied levels of sophistication, whether Bernabé would be successful appeared to be the question on most people’s minds even as some of them wondered who this Dimas Jiménez was, anyway, and by what right was he making these changes, Pratt’s letter notwithstanding. Was the communication really from Pratt?

At least by age eighteen or so (ca. 1912), Bernabé Parra had begun his work for Rafael Monroy as a field hand at his El Godo ranch, later working up to an administrator. Parra had little if any formal schooling but, admirably, worked hard on his own to overcome this deficit. To improve his life he had come to San Marcos from Colonia Guerrero in the village of Tecomatlán, approximately eighteen miles away. His quick mind and ingratiating and loyal spirit soon endeared him to Rafael, his sisters, and their mother, Jesusita, and, eventually, nearly all the San Marcos members.

Jesusita and her daughters had taken Bernabé with them to Jesus Sánchez’s home to comfort that ancient-of-days member who was dying. Parra had accompanied the Monroys to their baptism in June of 1913[20] and within a few weeks had joined them as a baptized member of the Church.[21] A few weeks later Rafael had taken Bernabé as a traveling companion to a district conference in Toluca.[22] Rafael completely trusted Bernabé and quickly gave him administrative responsibilities and opportunities at his ranch.

Sometimes the civil war made it impossible for Monroy to be at El Godo for months on end. In 1913 his ability to pay his employees catastrophically declined, which in April of 1914 prompted Bernabé to return to Tecomatlán where he could take refuge with his extended family and perhaps find a remunerating job.

Political disturbances in San Marcos over the American-owned Toluca cement factory, prejudices against foreigners in general, and the persecution of the fifty San Marcos Mormons in particular[23] may also have figured in Parra’s decision to leave. Within a month following his exit, Natalia Monroy and her husband, Roy Van McVey, fled, deciding on the relative safety (for foreigners) of the port city of Veracruz.[24] At the same time, refugee members from Toluca and Mexico City were arriving in San Marcos. Everything was in flux, and members’ individual circumstances were highly varied.

Unaware of the executions until returning to San Marcos in July of 1915, less than a week after the horrific event, a shocked Bernabé Parra quickly checked on the Monroy family. On 25 July 1915, he took advantage of the first resumed Church meeting to make an impromptu oration. Such a young man, still he was able to fortify the Saints. In the ensuing weeks, he was decisively active as he helped members by assuming a strong leadership role in the branch without actually holding a leadership position. After a period, he returned to Tecomatlán, but in May of 1917, nearly a year later, he returned to San Marcos as a permanent resident.[25]

Jovita

Bright, energetic, fully committed and spiritually strong, Parra seemed confident he could revitalize the branch as its new president. However, he was young (age twenty-three), unmarried, and in love with Jovita Monroy, ten years his senior. One might think these were enough obstacles. There was more. How would Bernabé handle this?

Against the uncertainty of disease, the logic of actuarial statistics that separated their life spans by a decade, the disapproval of Jovita’s family because of the age differences, and the educational chasm that separated them, Bernabé and Jovita nevertheless shared their hearts and hopes for a life of togetherness in the gospel of Jesus Christ. In truth, there were not many options for the Monroy girls if they wanted to marry in the Church. Jovita and Bernabé set a date for their wedding, which would have happened ten days or so before Parra’s sudden call to be branch president. Elders Cándido Robles and Dimas Jiménez from Ixtacalco had arrived to marry them, and Jovita’s family, despite the reservations, had planned a joyous celebration. However, Jovita suffered from a crippling, perhaps autoimmune, disease triggered shortly after her brother’s execution two years earlier. Because of joint pain, she required crutches just to get around. Shortly before she was to be wed, Jovita’s condition suddenly worsened. Jesusita whisked her daughter to a hospital in Mexico City. With Jovita’s condition suddenly worsening, the wedding was shelved, at least temporarily. The young woman remained in Mexico City for three months, unimproved, and nearly died.

Bernabé was devastated. At the sacrament meeting a week before his call, the young man’s cousin, Daniel Montoya, who was directing the branch that week, took occasion to “comfort the young Bernabé Parra, citing the scriptures and saying, ‘When trials occur it is because God is closer to us and perhaps they may be God’s test of our faith.’”[26]

As Bernabé assumed the mantle of leadership of the San Marcos Branch, his heart was vicariously in Mexico City at the bedside of his intended wife whose ailment, he feared, would not only leave her crippled for life but might even cut it short. Thus, Bernabé took on his new Church calling carrying a heavy emotional burden, comforted somewhat in knowing that the Ixtacalco leaders were making frequent visits to the hospital to give blessings and encouragement to his intended and her mother and sisters.[27] Jovita did not return to San Marcos until December, three months after the date set for their anticipated and now halted wedding. If Bernabé was depressed, he had ample reason.

Pratt Returns to Mexico

By the beginning of 1917, civil war disruptions had largely ceased in the municipality of Tula and elsewhere in central Mexico, replaced in part by sporadic banditry in the countryside and unbridled lawlessness in the cities as successive governments strove to reestablish civic order. Nevertheless, by September of that year, life was sufficiently secure that mission president Rey L. Pratt could return to Mexico briefly with a group of foreign missionaries to try to revive the Church in central Mexico. Pratt also called local full-time missionaries to assist him. Of course, all of them were interested in San Marcos.

President Pratt and a contingent of missionaries visited San Marcos in December of 1917, arriving just in time to celebrate the baptisms of Trinidad Hernández of Santiago Tezontlale and Dolores Martínez de Estrada, Bernabé Parra’s foster mother of nearby Guerrero. While living in Tecomatlán, Bernabé had worked to bring these and other everlastingly influential souls into the Church.[28] Despite Parra’s youthful age, he clearly had wide-ranging influence within and outside his extended family and had no hesitation in being an unofficial emissary of the restored gospel.

In San Marcos, mission president Pratt made a curious decision. Thinking he needed to further legitimize Parra’s leadership and concretely demonstrate his approval of Elder Dimas Jiménez’s role in ordaining him and setting him apart, Pratt ordained Parra an elder again, and again set him apart as the branch president, doing so in front of the congregation. No doubt, he also did some public explanation and perhaps some remonstration. Several members had complained that Jiménez did not have the “real” authority to establish a new branch president in San Marcos.[29] However, in attempting to address these perceptions, Pratt’s choice of means could do nothing other than undercut Jiménez’s authority as his emissary. Institutionalization of the Church in San Marcos would yet take time.

A Spirit of Contention

A spirit of contention had taken hold of some of the members in San Marcos, even tearing a few member families apart. Aside from the issue of the new branch president, Jesusita’s sister Juana Mera and her son Isauro Monroy Mera, baptized in March of 1914, were upset that Bernabé, as a prospective Monroy in-law, had been given an economic advantage at El Godo, which they felt should have gone to Isauro. Isauro was particularly distressed because Jesusita had replaced him with Bernabé as the ranch steward (mayordomo). After a period of acrimony, in 1918, Juana renounced her sister and left the Church.[30] Isauro Monroy tried to repress his offense, but when ex-President Casimiro Gutiérrez took to the pulpit to accuse him of “certain sins” and publicly reprimand him, he also withdrew from the Saints and did not return until advanced in age.[31]

Casimiro was still struggling with repairing his own life, apparently concluding that one way was to remonstrate others as they had done him. Some were offended and stopped attending the meetings. Other members stopped attending Sunday services because they had grievances with the Monroy family, and Church services were being held in the Monroy home. Never mind that it was the only available place of sufficient size to accommodate the members. Where was Christ in their lives? Some San Marcos Saints were constantly toiling to remember.

Alarmed at the loss of members in San Marcos, more local missionaries showed up to fortify the Saints, including Juan Mairet and Tomasa Lozada. Daniel Montoya and Bernardino Villalobos joined Bernabé Parra as counselors in the branch presidency and worked tirelessly to hold many of the members together in a community of the faithful. After 1921, foreign missionaries helped in the branch again as well—at least until 1926 when, once again, they were forced to leave the country (due to the Cristero rebellion).

Newly minted Bernabé Parra could not repair fractured relations among all the members, but he could deal with the building issue. In January of 1919, someone made a proposal that if holding meetings in the Monroy home was objectionable, then they should build a chapel. Parra agreed and began to organize the project. Within several years, aside from erecting the building with little help from Salt Lake City, the members also made their own furniture. In the process of working together, they drowned many sorrows and complaints and strove more diligently toward a gospel culture that embodies Christ’s teachings for the behavior of His people.[32]

Making furniture for the first chapel in San Marcos, ca. 1930. Left to right: Bernabé Parra, Benito Villalobos, Othón Espinoza, and Van Roy McVey. Note that Parra is holding a handsaw used in the difficult task of ripping boards for the benches. Courtesy of Church History Library. Copied from the original in possession of María Concepción Monroy de Villalobos, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Mexico.

Making furniture for the first chapel in San Marcos, ca. 1930. Left to right: Bernabé Parra, Benito Villalobos, Othón Espinoza, and Van Roy McVey. Note that Parra is holding a handsaw used in the difficult task of ripping boards for the benches. Courtesy of Church History Library. Copied from the original in possession of María Concepción Monroy de Villalobos, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Mexico.

Parra Stumbles

Bernabé Parra was still single, and his once-intended Jovita was still unable to walk without crutches. The ardor of their love had not completely cooled, but circumstances had dampened it. Parra was twenty-five or twenty-six; Jovita, thirty-five.

With nearly all the members in San Marcos without remunerative work and scratching whatever they could from the soil or wherever else to sustain life, Bernabé decided he should temporally leave the community again to search for employment elsewhere, which would take him away from the branch for a period. Thus, after a year of ecclesiastical labor as branch president, he wrote to mission president Rey L. Pratt about the difficult economic matters he and others were facing and informed Pratt of his desperate need. Although the record does not enlighten us, it is probable that he had Jovita edit his letter before sending it. The Mexican postal service had resumed normal operations in central Mexico, and in due course Pratt received Bernabé’s communication.

Because of Parra’s leadership skills and forthright dedication for a year as branch president, because Parra would be returning—perhaps soon—and because Pratt had no information regarding an adequate replacement, the mission president felt it unwise to release Parra outright. Pratt opted to appoint Daniel Montoya Gutiérrez, then a teacher, to preside during Parra’s absence. On occasion, Montoya had conducted Sunday services at the election of the congregation when the Casimiro Gutiérrez presidency was not functioning, so he had some administrative experience.

Pratt instructed elders Cándido Robles and Juan Haro from Ixtacalco and San Pedro Mártir to make the change in branch leadership, apparently not advising them to ordain Montoya an elder, a move that would have facilitated his interim presiding. In those days, advancements in the priesthood were generally slow in being made, and then only after much deliberation and a demonstration of substantial need. In San Marcos, the leadership transition—without advancement in the priesthood—occurred 16 February 1919.[33]

Over the next several months, many local missionaries traveled to San Marcos to help.[34] In August, Agustín Haro returned, this time in the company of Isaías Juárez. They showed up ostensibly to assess how well the branch was functioning. Juárez, a man of substantial Church experience and a natural leader who later would lead the Church in central Mexico during troubling times, made a titanic impression on the San Marcos Saints. “No one slept during his powerful oration.”[35]

In the meantime, Bernabé had successfully obtained a remunerative position, which resolved one aspect of his life but left him, quite naturally, pining for love and an association with the Saints. No doubt, he also missed his role as the San Marcos Branch president. Did he miss Jovita, too? Were they writing to each other? We have no answers.

Jesusita had a reconciliation of sorts with a few of her deceased husband’s sisters living in Arenal. Coincidentally, her daughter Jovita was anxious to “get out of the house” and decided that with the help of Eulalia, Vicente Morales’s widow, she could make a trip to see her paternal aunts and renew some aspect of the family’s former solidarity. Her aunts could assist her in exercising her joints, thereby improving her mobility. Jovita and Eulalia were gone about three months (from around late August to late November 1919).[36]

Bernabé Parra’s new work placed him near Arenal. Would this be a time to reconnect with Jovita while she was visiting her aunts? Did he and his once-intended continue to have feelings for each other? Did they still have any prospects for a marriage?

If he or she tried, a sufficient rekindling of their affection did not occur. What did occur was a furtive union between Bernabé and Eulalia. Amidst the heartache of the times, Parra’s youth and desperate loneliness, Eulalia’s tender age in widowhood, Jovita’s illness, and the prevailing culture that hardly registered disapproval, Eulalia and the otherwise Mormon stalwart Bernabé Parra produced an out-of-wedlock child whom Eulalia named Elena Parra Mera.[37]

Surely, it must have been a hard time for Parra and Eulalia. Parra appeared to have returned to San Marcos about the time that Jovita and her domestic helper did, perhaps not yet knowing that Eulalia was pregnant. In the meantime, as expected, he resumed his position as the branch president.

The culture of the times notwithstanding, as soon as the pregnancy became visible and the event in Arenal no longer deniable, Jesusita was furious.[38] The Church was, too. No doubt in consultation with Rey L. Pratt, Bernabé’s priesthood was suspended and his position as branch president terminated.

Despite Jesusita’s fury at Eulalia and Bernabé, and notwithstanding Jovita’s tragic jolt into considering her own future, illness or not, Parra reconciled himself with both mother and daughter. Jesusita, who seemed to have stood in the way of a marriage, now relinquished her opposition. Jovita, Eulalia’s pregnancy notwithstanding, now decided to accept Bernabé’s renewed marriage proposal. Bernabé had many good qualities—he was a natural leader, Church worker, believer in the Restoration, avoider of alcohol, advocate for the needs of others, and a good prospect to become the family’s permanent manager (mayordomo) at El Godo. She could absorb both his sexual relations with Eulalia and his illegitimate child.

The nuptials, accompanied by a large celebration that many outside visitors attended, occurred on 19 November 1920. Elder Cándido Robles returned—again—to perform the marriage, successfully this time.

Wedding of Jovita Monroy Mera and Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 13 November 1920. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Wedding of Jovita Monroy Mera and Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez, San Marcos, Hidalgo, 13 November 1920. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Five months later, Eulalia gave birth to Elena Parra Mera. Thereafter, Eulalia continued in Jesusita’s protective care along with the new baby and her and Vicente’s daughter Raquel. Generations in the Church trace their genealogy to Eulalia through her daughters Raquel and Elena.

Parra worked to rehabilitate himself. Eventually the Church pardoned him, and in June of 1921, six months after his marriage to Jovita,[39] restored his priesthood office. However, institutionalization of the Church in San Marcos would yet require time as the members struggled to live lives more consonant with a gospel culture. The many laudable features of the then Mexican culture notwithstanding,[40] San Marcos Mormons needed to distance themselves from some parts of their national ethos in which they and their forebears had been embedded for centuries. The Church’s teaching on chastity and sexual morality was a good place to start.

In the meantime, who among the Saints in San Marcos would be capable, if not willing, to take on the office of branch president?

Daniel Montoya Gutiérrez

On 8 December 1920, and in the wake of revelations about President Bernabé Parra and Eulalia Mera Martínez viuda de Morales’s fornication, Daniel Montoya was ordained an elder and set apart as the branch president in his cousin Bernabé’s stead.[41] Montoya’s prior interim appointment as acting branch president and his fierce dedication to the Church had given him some preparation.[42] However, his educational deficits were as pronounced as Parra’s had once been, and his reserved, guarded, almost withdrawn personality, complicated his life as a Church leader. Nevertheless, embedded faithfully in the Church’s teachings, as he understood them, Montoya stepped forth cautiously in this, his new appointment, to do what he could to help the San Marcos Saints progress and develop.

As did others of the period, Montoya had direct links to the increasingly revered Rafael Monroy, whose accorded stature in death sometimes exceeded the reality of his life. Nevertheless, Daniel could point to Rafael’s having baptized and confirmed him.[43] He had significant knowledge of Rafael’s positive relationships with members and nonmembers[44] and was one of the few male members who dared to stand with the Monroy women after the martyrdom even though he had spent some of the time in the Monroy’s chicken coop hiding from rebel Zapatistas.[45] All this gave him credibility with the Saints.

Montoya Overcomes Some Deficits

Still, the deficits were substantial for a young man in this position, married though he was. Having spent his entire life since childhood working in the fields as a campesino, he had come to San Marcos as an unschooled and illiterate adult, a condition he had not significantly altered by the time of his appointment as the new branch president. However, with the calling came a ferocious desire to throw off his mantle of ignorance and learn directly from the sacred texts. In time, he learned to read the scriptures haltingly so that he could teach others, many of whom were even less literate than he.

The local missionaries from San Pedro Mártir and Ixtacalco alternatingly paid monthly visits to give instructions, advice, cautions, and even reprimands based on the scriptures. In addition, from time to time other missionaries came, some of whom continued to make smashing impressions on the Saints in San Marcos. Among these were Abel Páez and Margarito Bautista, two who later would figure prominently in dissident movements resulting in their excommunications from the Church.[46]

All these eventual circumstances notwithstanding, during Montoya’s presidency the branch seemed to march along in a steady way.[47]

A New Chapel and a Regional Conference

Because contentiousness about having to meet in the Monroy home for Church services, in 1919 under the presidency of Bernabé Parra the Saints had decided to build themselves a modest chapel (casa de oración). They had laid the foundation and started construction on the walls amid concerns about how they could provide enough volunteers and raise enough money. Their principal expense would be the roof because they were making the walls out of adobe bricks by using centuries-old effective and affordable building techniques.

New branch president Daniel Montoya thought they could do it. He continued to give the project encouragement and direction despite its not being his original idea. Bernabé Parra, the old branch president, thought they could do it. Although defrocked, he continued to help finance the construction through his own resources and those of the Monroy family. Jesusita and other opinion makers in the branch thought so. They contributed not only their wherewithal financially but also the enthusiasm of their hearts and the labor of their hands. Charismatic visitors such as Margarito Bautista and Abel Páez thought so. They gave stirring, eloquent orations in support. President Rey L. Pratt sent funds to purchase sheet metal for the roof.

All redoubled their efforts when President Rey Pratt scheduled a regional conference for San Marcos for August 1921, barely two years after the idea of a building had first surfaced.[48] The excitement and almost feverish construction labor aside, the members were not able to get the windows installed in their new building in time for the conference. Nevertheless, they had everything else ready, and the conference unfolded with considerable satisfaction and good feelings.

Jesusita and her daughters remembered the conference they had attended in San Pedro Mártir and how it had helped them decide to become members of the Church. The Monroys, and all others who could, worked busily to receive the many visitors from afar who came to attend. They arranged for food and overnight accommodations, just as in the other regional conferences that members had attended.

The most anticipated event was the scheduled appearance of President Rey L. Pratt. The entire Mormon community was excited that he would be at the conference. Mexican Mormons had a profound affection for Pratt, which the president reciprocated with love, unbridled service, and much personal sacrifice on their behalf.

Jesusita had her piano hauled to the new building for the services so that her daughter Guadalupe could play it for the hymns, which was important since the hymnals themselves had no music staffs, only text, and, in any event, no one outside the Monroy family could read music. In the afternoon session, the clerk read from the pulpit the names of members who had donated to the building fund and the amounts of their contributions, certainly an unusual occurrence in a Mormon congregation.[49]

As usual, Pratt’s preaching captured everyone’s attention. The uninstalled windows notwithstanding, he also gave a stirring dedicatory prayer. In the evening, he conducted a “very animated” testimony meeting. The Saints loved testimony meetings, which they held at every conceivable opportunity. The following Monday, thirteen more people were baptized.[50]

For his part, branch president Daniel Montoya conducted the proceedings of 27 August 1921 with dignity and grace and with a level of confidence that bespoke well of his growing maturity in the administration and conducting of Church affairs. Overall, the conference, the arrangements, the chapel dedication, the orations, the presence of Pratt, the testimony meeting, and the baptisms were a superb success. If excitement about being in a new cause and building a conviction to sustain it is a prerequisite for institutionalization, the Saints in San Marcos were on their way—that is, were it not for another round of chaotic events.

Chaos

Personal failings alien to a gospel culture soon dampened the lingering conference enthusiasm and pleasure of having their chapel dedicated. President Montoya’s first wife, María Manuela Cruz Corona,[51] had an affair with a nonmember, a matter that traumatized the branch president and sent him to the municipal (county) seat of Tula to sue for divorce. Before the 1914 reforms in the civil code, divorce in Mexico was extremely difficult, if not impossible, for the poorer classes, which was one alleged reason why poor people tended to have common-law unions rather than marry in the first place.[52] (The baptisms of many of the first adult members had to await the formalities of moving their concubinato [common-law] unions[53] to a married state blessed by civil authority.)

The snail-pace divorce proceedings became acrimonious. Branch members developed opinions as to who was at fault, which of itself fueled considerable gossipmongering.[54] At a dispassionate level, some wondered if it was Daniel Montoya’s sacrifice of time and personal resources for the community of Saints that had caused his wife to consider his service a cost beyond either her willingness or capability to endure. Nevertheless, Montoya carried on alone for a while until revelations emerged that he and his estranged wife, María Manuela, had also been unchaste before their marriage.

With these disclosures and for perhaps other reasons, Montoya was released as branch president. The divorce process was fraught with public shaming, as the Saints resorted to punitive enforcement before they learned how to live a gospel culture that embraced loving discipline. Institutionalization would yet take time. Not until 1925 were Daniel Montoya and his new wife, Margarita Gutiérrez Sánchez, allowed to partake of the sacrament again and become fully reintegrated into the community of the faithful.[55] Nevertheless, both continued to attend Church meetings and contribute financially to the San Marcos Branch. The depths of their eventually complete repentance sustained them during the opprobrium and shunning and kept them and large numbers of their descendants in the Church.

Margarito Bautista visited the branch again, specifically to warn the Saints to have charity with fallen brothers and sisters given that everyone is weak and prone to sin. He admonished the members to always ask God to fortify them in their faith that they might remain faithful.[56] As usual, Bautista had a charismatic aura about him.

Loose attention to the law of chastity had undone three of San Marcos’s four branch presidents. However, little by little the Church’s teachings made behavioral inroads into the lives of the Saints, not the least of which was the principle of repentance. People fall. They make terrible mistakes. However, with sincere intent and repentant hearts reaching for the heavens, the Savior more quickly reaches out to sinners than do their neighbors. From their mistakes, the fallen can learn to live a better life. With the Savior’s love, the repentant can develop a conviction to live what they have learned. So the members learned, and so it was. For most of them.

In the meantime, San Marcos needed another branch president. Benito Villalobos Sánchez, the branch’s fifth, was set apart on 1 September 1923. With a new building, however modest by present standards, and with many new members learning the gospel (and new and old members trying to live it), would Benito be able to provide the careful guidance that might lead the Saints into a discovery of how to live gospel-centered lives more adequately? Would the Church become more institutionalized on his watch?

Benito Villalobos Sánchez

Benito Villalobos Sánchez got off to a rocky start when, the week following his appointment as branch president, he failed to show up for the meetings. A priest, Othón Espinoza, a recent immigrant and one who would later figure prominently in the dissident Third Convention movement as an assistant to Abel Páez, presided over the meetings, he being one of President Villalobos’s counselors.[57] Nevertheless, Benito soon got the time constraints on his life squared away and thereafter presided over the branch until about 1926.

As with previous branch presidents, intense learning characterized Villalobos’s tenure, not only in regards to conducting meetings but also in some of the finer points of Church doctrine. He started out young and timid but in less than three years grew in maturity and self-confidence. This served him well, given that during his presidency, contrarian voices entered the Church’s proceedings, principally in the person of Margarito Bautista.

The Challenge of Margarito Bautista

In the three months following Benito Villalobos’s setting apart as branch president, Margarito Bautista showed up on numerous occasions to preach his stimulating, nationalist-flavored version of the Book of Mormon and the Restoration, apparently even after his release as a full-time missionary.[58] Other full-time missionaries began to take an increasing role in branch administration to help President Villalobos address this challenge. The matter grew to sufficient concern that in December of 1923, President Pratt showed up to preach a gentle sermon that some interpreted as being “anti-Bautista.”[59]

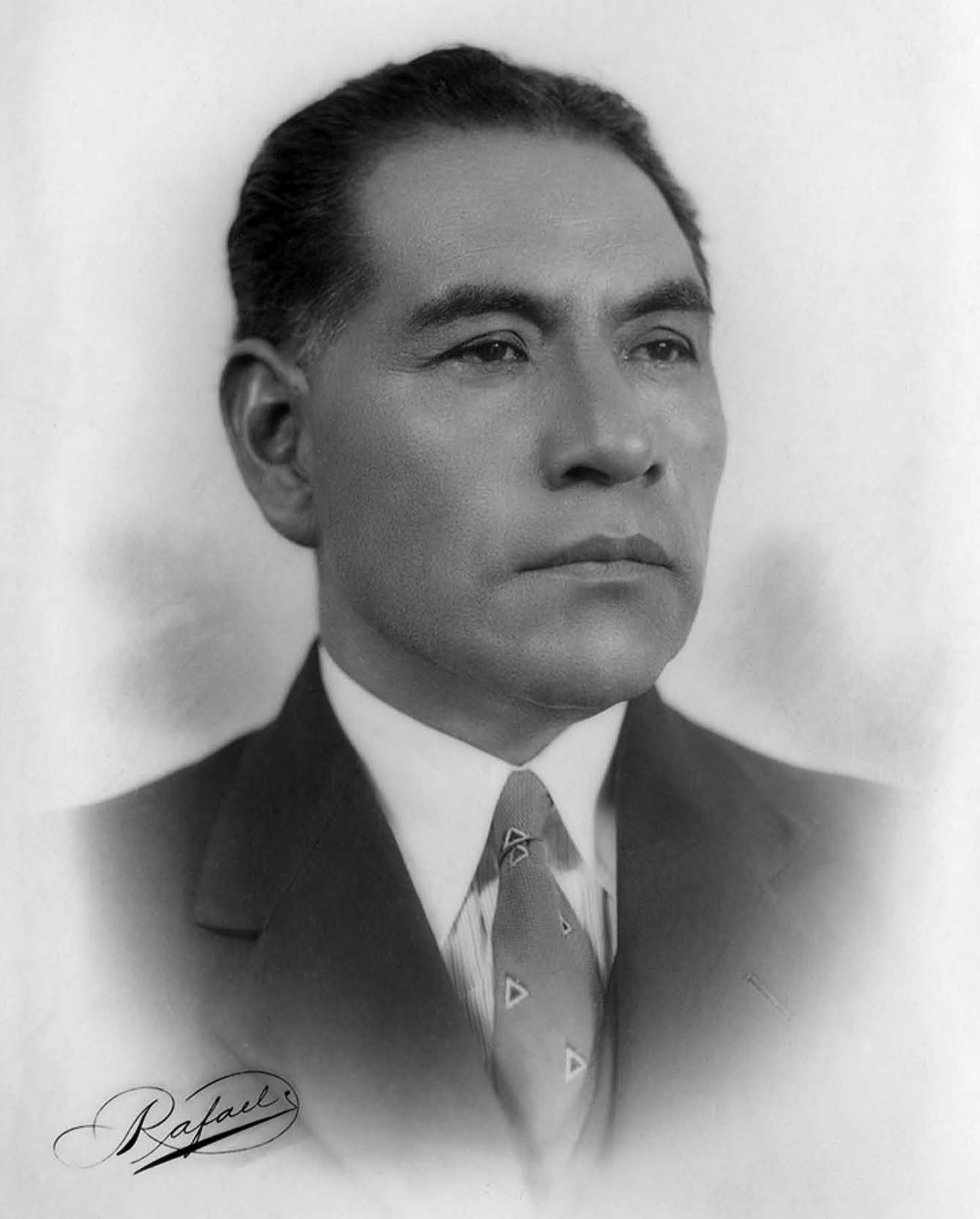

Margarito Bautista, 1933. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Margarito Bautista, 1933. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In the ensuing months, Bautista’s influence only grew. Through his frequent visits to San Marcos, Bautista was making inroads there (and elsewhere) that Pratt did not like. In March of 1925 at a newly called regional conference in San Marcos, an infuriated mission president addressed his ideas without attacking Bautista personally. Surprised, members listened intently to an uncharacteristically angry Pratt preach a robust and tough sermon against ideas alien to the gospel of Jesus Christ.[60] Members wondered what had caused the outburst and what his sermon meant to them personally. San Marcos appeared to become the whirlpool of one of the fights that eventually exasperated the Church and eventually led to Bautista’s excommunication.

Bautista, who had spent much time teaching about temple work and organizing local genealogical societies complete with administrative personnel whom he encouraged to have full-bodied nationalist sentiments (e.g., the eventual religious triumph of Mexicans over their Anglo overlords), had already left for a lengthy stay in the United States, where he would further embellish his thinking before returning again to Mexico. Before, he had been a dedicated and effective missionary. Now he was pursuing his own gospel and confusing people about some aspects of Church doctrine and administration.[61] However, he did have a legacy achievement. He increased people’s interest in their genealogy.[62]

Developmental Transformations

It was not all stress and distress for branch president Villalobos. People were returning to San Marcos following the civil war’s dislocations. Along with other members whom the war had further immiserated, by 1925 (perhaps 1928), Roy Van McVey and his wife, Natalia, had returned to Mexico where McVey picked up his employment at the Tolteca cement factory. They were living in a handsome home the company had provided.[63] McVey and Natalia had spent several years “exiled” in Texas, where McVey joined the Church and he and Natalia, Jesusita’s daughter, had traveled to a temple to be sealed.[64] Both were a strong support to the Church in San Marcos.

Aside from displaced members returning to San Marcos, the Saints frequently held baptismal services for young eight-year-olds born to members in addition to the customary convert baptisms, which sometimes included entire families. Some people who had been displaced and uprooted and had seen their life’s expectations torn asunder were available for new value commitments. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints appealed to some of them on a variety of fronts.

In his stirring, stunning, aggressively forceful oration at the March 1925 regional conference in San Marcos, Pratt had mentioned that the chapel the Saints had constructed was not large enough. During some meetings, would-be attendees listened to the proceedings from outside the building’s windowless, framed portals. It would be a while before the Saints could respond to Pratt’s observation, but the idea germinated in their minds. By 1926, they were holding fund-raisers in order to enlarge their meeting house as Pratt had recommended.[65]

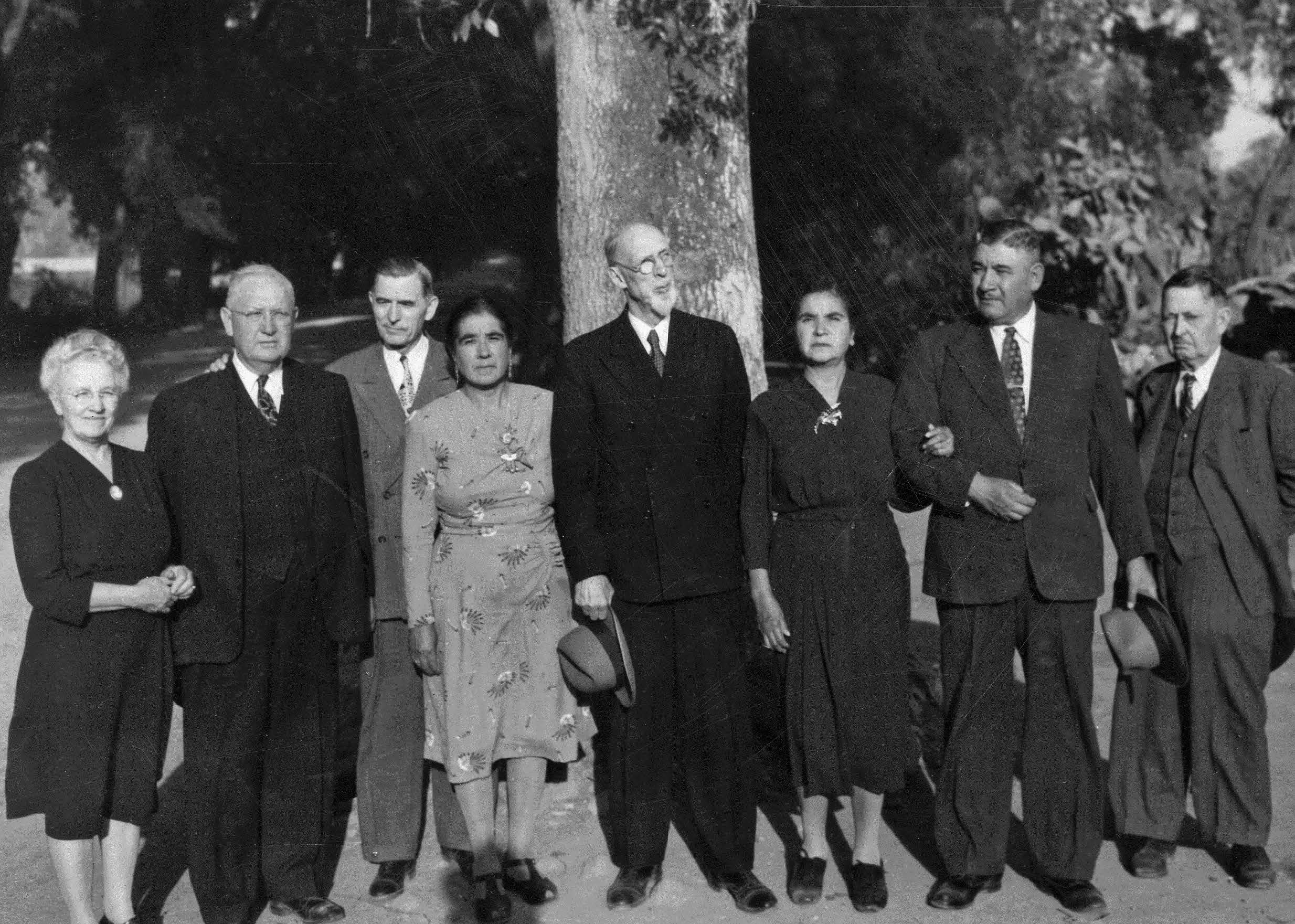

Photo taken adjacent to the first San Marcos chapel during the visit of Apostle Richard R. Lyman, August 1925. Front row, left to right: María Guadalupe Monroy, Jovita Monroy de Parra, Jesusita Mera de Monroy, Guadalupe Hernández de Monroy. Middle row: María Concepción Monroy, Amalia Monroy. Back row: Bernabé Parra, unidentified man, Apostle Richard R. Lyman, President Rey L. Pratt. Man standing by the cornfield unidentified. Man at right is Amando Pérez. Courtesy of Church History Library. Copied from the original in possession of María Concepción Monroy de Villalobos, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Mexico.

Photo taken adjacent to the first San Marcos chapel during the visit of Apostle Richard R. Lyman, August 1925. Front row, left to right: María Guadalupe Monroy, Jovita Monroy de Parra, Jesusita Mera de Monroy, Guadalupe Hernández de Monroy. Middle row: María Concepción Monroy, Amalia Monroy. Back row: Bernabé Parra, unidentified man, Apostle Richard R. Lyman, President Rey L. Pratt. Man standing by the cornfield unidentified. Man at right is Amando Pérez. Courtesy of Church History Library. Copied from the original in possession of María Concepción Monroy de Villalobos, San Marcos, Hidalgo, Mexico.

Apostle Richard R. Lyman was enthralled with the Saints in San Marcos, whom he visited in August of 1925—the first Apostle ever to do so.[66] Aside from fledgling foreign missionaries, his visit may have been the first time the San Marcos Saints had ever heard a discourse through an interpreter.

An interpreted message from an Apostle was enough for some. Others, such as branch presidency counselor Othón Espinoza, were “disgusted” at having to listen to such a high-ranking General Authority speak thusly. “The Spirit of the Lord should give him the gift of tongues.”[67] There was a lot of institutionalization that yet needed to occur in San Marcos. In the meantime, Bernabé Parra and Jovita Monroy received Apostle Lyman in their home.

The two positions—acceptance and rejection of the linguistic limitations of an Apostle—mirrored a gnawing concern about whether the Mexicans would have “their” church or whether they would always be beholden to Anglo-Americans for their tutoring, and that through an interpreter. After a flurry of discussions, most San Marcos members settled on remaining loyal to Rey Pratt and the leaders in Salt Lake City. A few would later drift away, but not many.

From time to time, the troubling issue of the Church’s prior practice of plural marriage (polygamy) stirred people’s sentiments, distressing the San Marcos Saints greatly because it gave the Catholics another opening through which to attack them.[68] However, the difficulty with this doctrine was even more complicated. When around 1925 President Benito Villalobos heard of a clandestine plural marriage having been performed “up north,” well past the time when such practices should have officially ceased in the Church, he was upset beyond an ability to cope and could not carry on further as branch president.[69] His neighbors’ taunting made the doctrinal confusion intense, which, for him, became unbearable and led to his resignation as branch president.

Fortunately, Villalobos’s decision did not take him away from the Church for long, because he knew that the gospel’s underlying doctrines were true and far outweighed human-caused aberrations or imponderable doctrines at whatever level. His enduring testimony has bequeathed the Church at least five generations of faithful members, now scattered throughout Mexico and beyond.

With President Benito Villalobos gone, now who would lead the branch through its growth epochs as well as troubling times? The Church again tapped the ever-present, ever-ready, ever-willing, and now-rehabilitated Bernabé Parra. Beginning his adulthood as a quasi-illiterate man of the soil (campesino), he had risen to become a powerful force in the Church and in the community of San Marcos generally, his personal flaws notwithstanding.

The Return of Bernabé

Bernabé Parra was among the second wave of people to join the Church in San Marcos. He had been with the Monroys from the beginning of their commitments. He had been to regional conferences, had received personal instruction from mission president Rey L. Pratt, and had acquired experience during his first tenure as branch president. Moreover, he had been instrumental in getting a building project under way. Beyond those accomplishments, he had left his work as a field laborer during some of his absences from San Marcos to become an accomplished technical wage earner in electricity as the country’s rural electrification projects had gotten under way. This, in addition to his enthusiasm for the gospel, made him a man to admire, his affair with Eulalia Mera aside. Indeed, branch members saw that he had repented and rehabilitated himself during the previous six years, which seemed to make him all the more attractive as their leader. He understood their travails. Here was a man, now the de facto head of the Monroy family, whom they could admire and seek to emulate in his repentant state, happily receiving his counsel and following him as their leader.

The records available to us do not disclose whom Parra selected as his counselors in the new branch presidency. However, he, and no doubt his counselors, too, went right to work to heal wounds and to bring a welcomed, assertive commitment to the branch through vigorous, purposeful direction.

Aside from members’ commitments to the faith’s principles and values, the Church’s institutionalization in any given area requires leaders who can help others internalize value commitments and followers who are willing to accept guidance through life’s pathways. San Marcos had come a long way from the early days of tender testimonies, martyrdom, jealousy, leadership failings, and the chaos of a civil war. There would still be problems, but if not fewer, they were certainly less intense.

The weekly sermons at sacrament meetings, the Sunday School lessons, the impromptu testimony meetings held in diverse locations, the personal visits to members’ homes—all were designed to enhance the Saints commitment to the Church and to show them how to live their lives in accordance with gospel teachings. In short, Parra designed his whole operation to help members learn a gospel culture and incorporate it into their lives. For some it was a long journey. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that so many engaged in the effort and indeed made considerable progress.

A New Building Project and Local Leadership Development

By 1926, the San Marcos Mormons had engaged their building project again with an intensity that matched branch President Parra’s enthusiasm, holding more fund-raisers and formulating plans for a significant addition to their meetinghouse.[70] Slowly, with more civil disturbances during a Catholic (Cristero) rebellion against the government (1926–29) notwithstanding, they proceeded, even to the point that Parra commissioned a large mural of the Salt Lake Temple to adorn the stage behind the pulpit.[71]

Interior of the second chapel at San Marcos Hidalgo that the members constructed. Bernabé Parra commissioned the mural of the Salt Lake Temple. This building has now been replaced. Photo from the Amalia Monroy de Parra collection, courtesy of the Church History Library.

Interior of the second chapel at San Marcos Hidalgo that the members constructed. Bernabé Parra commissioned the mural of the Salt Lake Temple. This building has now been replaced. Photo from the Amalia Monroy de Parra collection, courtesy of the Church History Library.

The effort to establish local leaders, such as Parra, throughout the Church in central Mexico had been vigorously underway since 1924. Mission president Pratt had learned that he would soon leave for Argentina to help introduce the gospel there.[72] Thus, prior to his departure in 1925, Pratt gave enormous attention to developing a leadership corps throughout central Mexico. Observers reported that the Mexican leaders he appointed functioned so well that the American missionaries could spend all their time proselyting new members rather than also trying to administer the branches.[73] Branch president Bernabé Parra was certainly among President Pratt’s success stories.

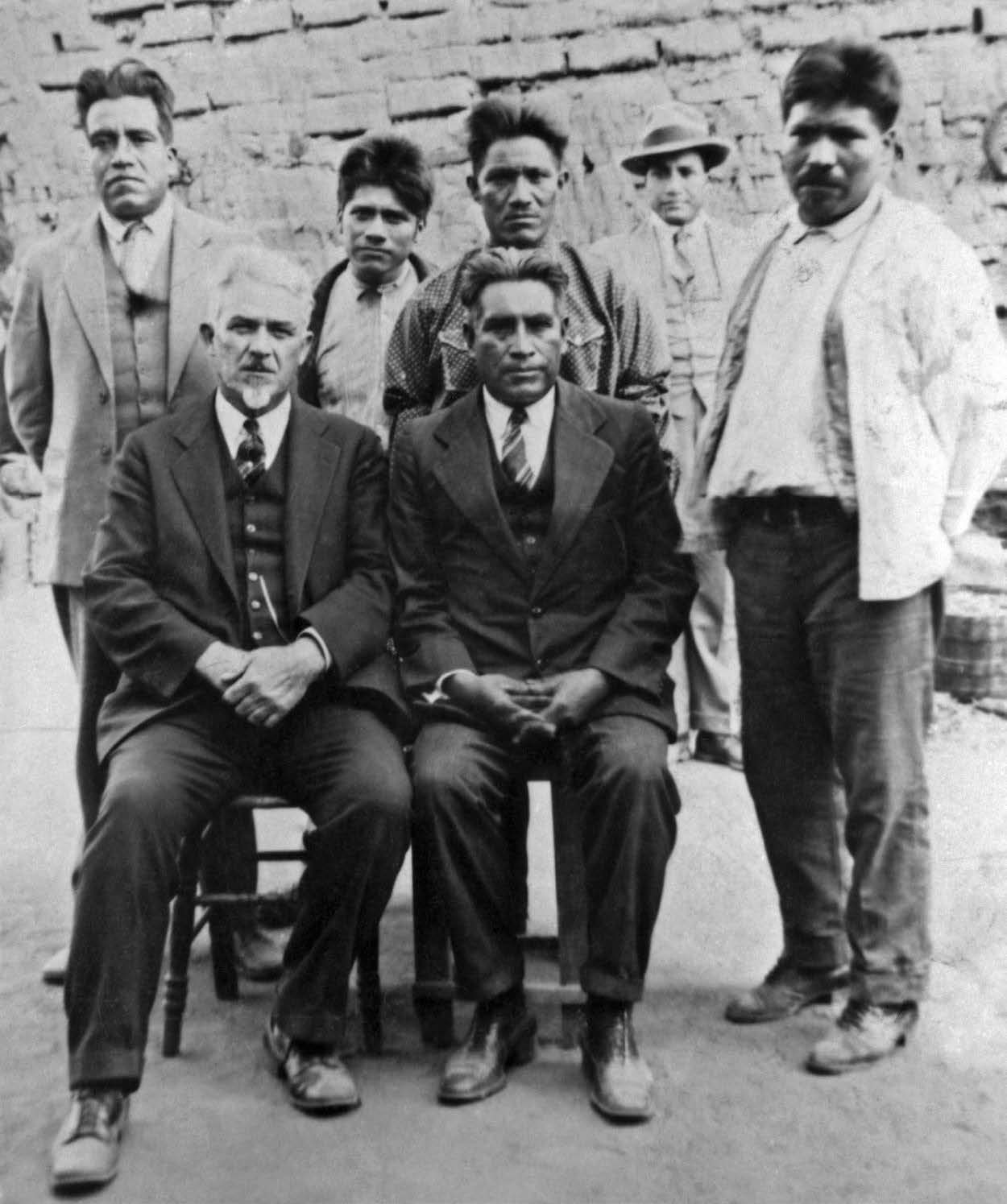

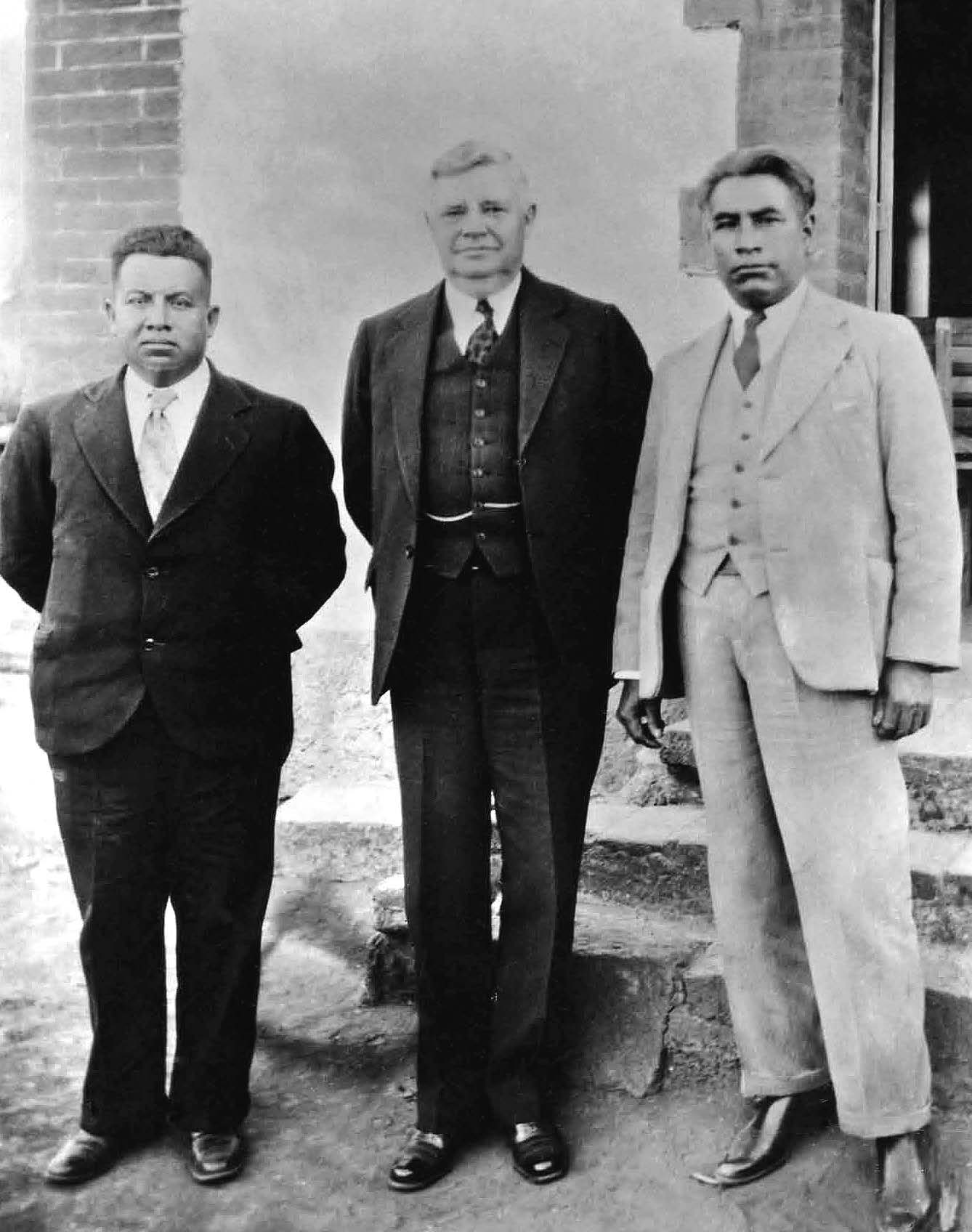

After Pratt’s return from Argentina, he went one step further in his local leadership development efforts by establishing a district presidency to give guidance with suprabranch authority to the Church in Mexico. The man he picked as district president was the grandest orator of them all, Isaías Juárez, with counselors Bernabé Parra and the still-in-the-fold Abel Páez, himself a man of considerable talent, skill, testimony, and willingness to serve.[74]

President Rey L. Pratt with Isaías Juárez (seated) and other members of the Church (David Juárez, Benito Panuaya, Narciso Sandoval, and Tomás Sandoval), San Gabriel Ometoxtla, ca. 1931. Man with hat is not identified. Courtesy of Church History Library.

President Rey L. Pratt with Isaías Juárez (seated) and other members of the Church (David Juárez, Benito Panuaya, Narciso Sandoval, and Tomás Sandoval), San Gabriel Ometoxtla, ca. 1931. Man with hat is not identified. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Abel Páez and Isaías Juárez, district counselor and president in central Mexico, with US ambassador to Mexico J. Reuben Clark Jr., ca. 1931. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Abel Páez and Isaías Juárez, district counselor and president in central Mexico, with US ambassador to Mexico J. Reuben Clark Jr., ca. 1931. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In some sense, appointing Bernabé Parra as branch president for a second time and then as a counselor in the newly formed district presidency was useful to the organizational structure not only of the Church in San Marcos but later also of the Church in the entirety of central Mexico. In 1926, the Mexican government under Plutarco Elías Calles—an “anti-Catholic Free Mason atheist,” his enemies called him—enacted anticlerical legislation (in response to attempts by the Catholic clergy to undermine his government) known as the Law Reforming the Penal Code or, more crisply, as “the Calles Law.”

The Calles legislation outlawed religious orders, deprived churches of property rights, and stripped their clergy of civil liberties, including a right to trial by jury in cases involving anticlerical laws and the right to vote. Further, the new laws allowed the government to seize church property; close religious schools, convents, and monasteries; and expel all foreign priests.[75] In the municipality of Tula, and therefore in San Marcos, it being a constituent part of that municipality, authorities ordered foreign missionaries and clerics—Catholic, Protestant, Mormon, and whomever else—to leave the country on pain of imprisonment. The government gave them twenty-four hours’ notice.[76]

In the absence of the foreign missionaries, the local leaders Rey Pratt had prepared generally distinguished themselves well. The district presidency went into high gear to keep the branches well administered and to make it possible for the Church to carry on during this, the third time that Anglo missionaries had been forced to abandon their Mexican flocks.[77]

Bernabé Parra continued to distinguish himself on behalf of the Saints. Even during and after difficult times that later would befall him, he was remembered with great affection in San Marcos for his critical, influential, and effective work on behalf of the Church there.

Bernabé’s Release and Subsequent Fall

Bernabé Parra was released as San Marcos’s branch president in order to join the newly formed district presidency and thereby serve with President Isaías Juárez and Juárez’s other counselor, Abel Páez, as supra-branch authorities. Parra’s successor in San Marcos, Maclovio Villalobos Sánchez, who became the seventh president of the San Marcos Branch, was then set apart. Thereafter, quite routinely, Agrícol Lozano Bravo, Sabino Lozano, and Marcelino Cerón followed as branch presidents, which provided functioning presidencies in San Marcos through 1952.[78]

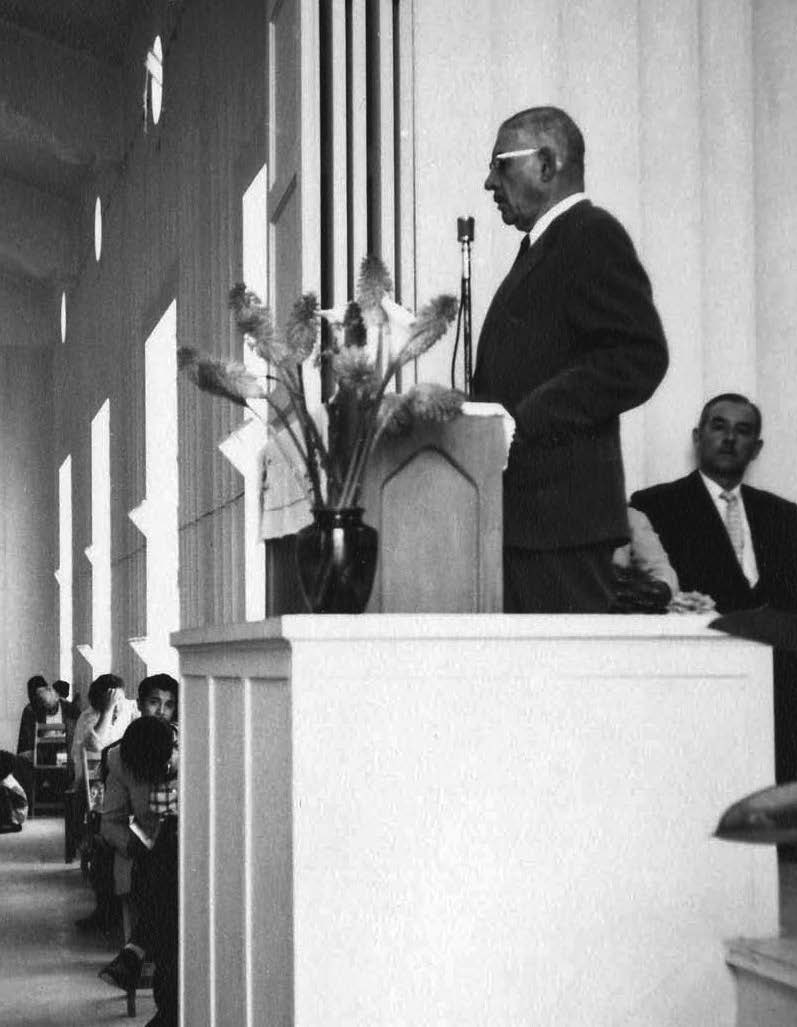

Bernabé Parra preaching in the San Marcos Chapel, 1966. Collection of Amalia Monroy de Parra, courtesy of Church History Library.

Bernabé Parra preaching in the San Marcos Chapel, 1966. Collection of Amalia Monroy de Parra, courtesy of Church History Library.

Agrícol Lozano Bravo, Sabino Lozano, Marcelino Cerón, and the Saints in their charge continued their work to institutionalize the Church in San Marcos and encourage the development of a gospel culture among the people who joined it. Sometimes the pathway continued to be not only serpentine but also rocky. Nevertheless, during these administrations the Mormons began to more closely understand the cultural, behavioral, doctrinal, and faith requirements of an institutionalized church—their church.

For Bernabé, there were setbacks following his appointment as a counselor in the district presidency. Around 1935, some nine years after his selection, Parra commenced an illicit union with Amalia Monroy that within three years produced two children.[79] Parra was once again defrocked—this time excommunicated[80]—losing his position in the district presidency, his membership in the Church, and all his priesthood blessings. All Parra’s great accomplishments notwithstanding, the drag of traditional mores was more powerful than Parra’s partially acquired inhibitions and commitments as a Church leader. It would take him a decade to reclaim his membership and receive his priesthood blessings again.

María Guadalupe Monroy Mera; María de Jesús Mera Vda. de Monroy; Amalia Monroy, 1933.

María Guadalupe Monroy Mera; María de Jesús Mera Vda. de Monroy; Amalia Monroy, 1933.

Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Parra’s scorching desire for more children of his own that Jovita could not give him, coupled with the powerful temptations that had taken him down once before,[81] undid him anew. However, in his own mind, and in the minds of the Saints in the municipality of Tula whom he continued to support and defend all during the interregnum of his excommunication, Parra never ceased being a Mormon in spirit and desire.[82] Yet he knew he had to be held accountable for his personal failings.

Bernabé, his wife, Jovita, and his mistress, Amalia, coexisted until about 1945.[83] One of Amalia’s children speaks of Jovita as his loving second mother (mamá Jovita),[84] which suggests an affectionate and ongoing relationship over the years consistent with Mexicans’ love of children, even under these circumstances.

During the April 1946 reunification-of-the-Church meetings in Mexico that Church President George Albert Smith attended, including in the branch of San Marcos, mission president Arwell L. Pierce rebaptized Bernabé, and President Smith restored his priesthood blessings. Given that Bernabé and Jovita never divorced and that she lived until 1960, domestic arrangements that separated Amalia and Bernabé had occurred so that, once again, he would have been living a repentant life consistent with a gospel culture. What were those arrangements?

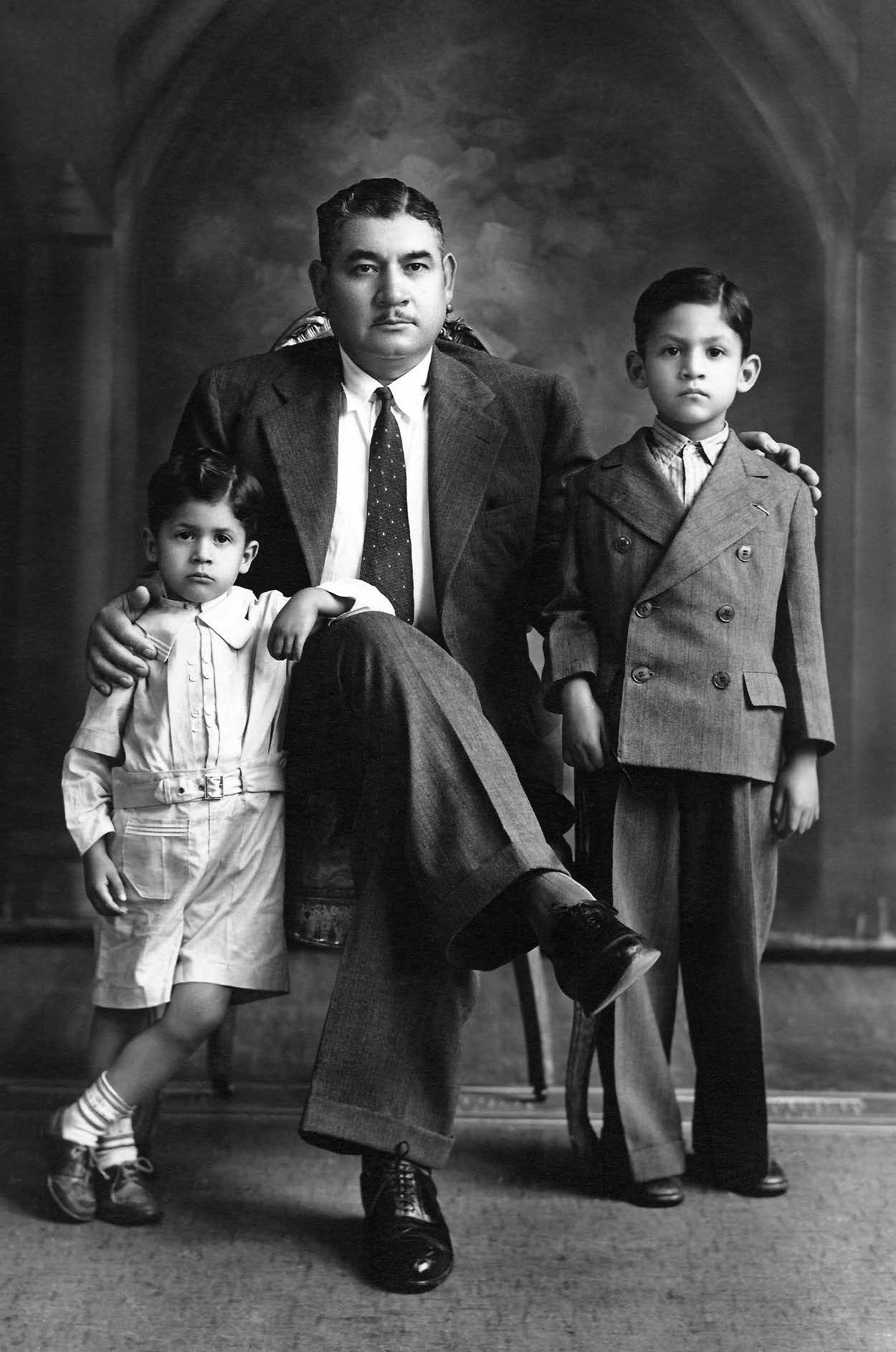

Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez, with his sons Bernabé Parra Monroy (left) and Benjamín Parra Monroy (right), ca. 1944. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez, with his sons Bernabé Parra Monroy (left) and Benjamín Parra Monroy (right), ca. 1944. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

For one, around 1945, Bernabé and Amalia stopped living together, convinced that, for them, this was the Lord’s will, their children notwithstanding (considering this was the only way that Bernabé could become rebaptized, a matter that had nearly consumed him since his excommunication ten years earlier).[85] Parra continued to interact with his sons, both of whom had great affection and respect for their father.[86] Parra supported them financially with living expenses, his youngest son’s mission costs, his oldest son’s university studies, and both sons through their middle school and high school (secundaria and preparatoria) education. He also may have contributed to Amalia’s household expenses for fifteen years before Jovita died, and Bernabé and Amalia subsequently chose in 1960 to reconnect with a legitimate marriage.[87] Whatever and how often one’s transgressions, the Lord, and the Church, are usually quick to respond to a contrite penitent, especially one whose testimony of the restored gospel never faltered even though his personal life did not yet fully embrace a gospel culture.

Another arrangement that reflected honorably on a contrite and repentant Parra and further sealed his sons’ affections for him occurred in 1947. In that year, Amalia left San Marcos for Mexico City, ostensibly to enroll her two children in a postprimary educational experience superior to what San Marcos could offer. The move also geographically disconnected Bernabé and Amalia and publically attested to the separation they had already decided upon. Parra nevertheless kept contact with his sons and financially supported them.

President George Albert Smith visited San Marcos for a “reunification conference,” April 1946. Left to right: Mary Brentnall Done Pierce, mission matron; Arwell L. Pierce, president of the Mexican Mission; Joseph Anderson; María Guadalupe Monroy Mera; President George Albert Smith; Jovita Monroy Mera de Parra; Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez; Van Roy McVey. On this occasion, Parra was rebaptized and his priesthood blessings were restored. Collection of Amalia Monroy, courtesy of Church archives.

President George Albert Smith visited San Marcos for a “reunification conference,” April 1946. Left to right: Mary Brentnall Done Pierce, mission matron; Arwell L. Pierce, president of the Mexican Mission; Joseph Anderson; María Guadalupe Monroy Mera; President George Albert Smith; Jovita Monroy Mera de Parra; Bernabé Parra Gutiérrez; Van Roy McVey. On this occasion, Parra was rebaptized and his priesthood blessings were restored. Collection of Amalia Monroy, courtesy of Church archives.

Both Amalia and Bernabé thrived on learning, turning every opportunity to provide their children a good education. Earlier, Bernabé’s educational thirst had become the Monroy family’s improvement project. Amalia, of course, raised in the Monroy household since she was eleven or twelve, acquired at an early age the family’s blistering desire to better itself educationally.

Amalia not only took her two sons, ages eleven and thirteen, with her to Mexico City but also the children’s cousin Enrique Montoya and their friend Efraín Villalobos.[88] She cared for them while they pursued their educational desires. Her sons and Efraín Villalobos, and most likely Enrique Montoya too, excelled in their studies. Afterward, at least three of them lent their prodigious energies and educational preparation to the benefit of the Church.[89]

Notwithstanding Bernabé Parra and Amalia Monroy’s domestic arrangements initially being contrary to the teachings of the gospel, these parents raised their two children in households of faith. Their service, as that of their children and grandchildren, has blessed untold numbers of people. The twice-defrocked Bernabé rose repeatedly to assist members in San Marcos, even facilitating in 1946 the formation of a private school (the “Church School” later named Héroes de Chapúltepec) to educate his own and others’ offspring, who otherwise would probably have fallen below a level of literacy and moral persuasion that Parra felt appropriate for the Saints. A most unusual feat for a man who never went to school.

Although Bernabé and Amalia fell into a pattern that was entrenched in traditional Mexican culture, and although Parra was anxious to have heirs that his wife, Jovita, could not give him, having these heirs with Amalia was nevertheless a profound departure from the long trek that adopting a gospel culture entails, especially for a leader of his stature. A national or regional culture antithetical to a strived-for gospel ethos is sufficiently hard to break that even the very elect may fall, as did, for example, Apostle Richard R. Lyman (who in 1925 had visited San Marcos) under analogous circumstances.[90]

Leadership and Institutionalization

Clearly, the impact of leaders is consequential in the Church’s transformation from ephemeral implant to an integral part of a community’s life. The process by which the Church’s doctrines, mission, policies, vision, action guidelines, codes of conduct, central values, and Restoration eschatology become integrated into the culture of its leaders and members and that its organizational structure is able to sustain through time is neither easy nor assured.

In San Marcos, the strength of most early leaders’ testimonies and convictions trumped their immense personal shortcomings to, on balance, leave among most members a positive introspection into their own lives:

Our leaders were as human as we—some with their alcohol, some with their women, some with their backbiting, some with their quick judgments that hurt others, and some with their spousal and parenting problems. Yet, together, we learned not only the doctrinal tenants of the gospel of Jesus Christ but also something of the culture in which it must be embedded. We still have our struggles, but we are a better people than we were. Our children, generally speaking, are an improvement upon us. Is this not the promise of progress that the scriptures and the prophets have foretold for those who, despite sometimes massive personal weaknesses, inadequacies, limitations, and failings, strive to find God and to serve him and, in so doing, make the world a better place in which to live?[91]

Notes

[1] The difficulty is illustrated at, for example, the sectorial level of ethics in any organization. See Ronald Sims, “The Institutionalization of Organizational Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 10, no. 7 (1991): 493–506.

[2] Eduardo Balderas, “How the Scriptures Came to Be Translated into Spanish,” 29.

[3] San Marcos First Ward and San Marcos Second Ward.

[4] The wards are Tula and El Huerto.

[5] Jasso Ward.

[6] San Lucas Ward, Iturbe Ward, El Carmen Ward, Atitalaquía Ward, Bominthza Branch, and Tlahuelilpan Branch.

[7] Clark V. Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico: The Rise of the Sociedad Educativa y Cultural” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1977), 64–77; Barbara E. Morgan, “Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 4 (2013): 89–95. The elementary schools were eventually phased out as improvements in Mexico’s public education system came on board. The flagship school, Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Americas (a high school), was closed in 2013 and transformed into a missionary training center. Barbara E. Morgan, “The Impact of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Américas, a Church School in Mexico,” Religious Educator 15, no. 1 (2014): 145–67.

[8] Basic information on Bautista and Páez may be found in Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, chs. 5–6.

[9] As an example, I list the Monroy family’s website, https://

[10] Agustín Haro may have been functioning as an ad hoc “district president” in conjunction with his role as branch president in San Pedro Mártir. However, in the wake of the dissolution of the San Marcos Branch presidency it was not he who appeared on the scene but rather Gabriel Rosales, one of the refugees in San Marcos who came out of hiding long enough to be of assistance. Gabriel Rosales’s only apparent connection with ecclesiastical authority was through Ángel Rosales, president of the Ixtacalco Branch.

[11] On the priesthood offices, see Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 32; on reconstituting a presidency of sorts, see “Carta de Jesús M. Vda. De Monroy,” 8.

[12] One such letter that arrived in May 1916 admonished Casimiro about his treatment of branch members that had pushed some of them from the Church. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 37.

[13] Guadalupe Monroy noted much discord between branch members and Casimiro as they struggled over their losses and insecurities. The stresses were horrendous and some families were falling apart. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 36.

[14] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 37, 39–40. In January 1917, Bernabé Parra was nominated to be ordained a deacon.

[15] Rosales presided over the Sunday meetings of 23 July 1916 and 14 January 1917 and probably others. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 38.

[16] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 42. The congregation selected Parra to lead the services of 4 August 1917.

[17] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 38, 40, 42. The service was for 17 July 1917.

[18] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 38, 40, 42. The personal attack occurred at the fast and testimony meeting of 4 August 1917.

[19] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 43.

[20] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 2, 4–5.

[21] Sanders Morales to LaMond Tullis, 11 February 2014; and Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 5. Bernabé Parra was baptized 28 July 1913. “Referencias del Diario de W. Ernest Young,” Linaje Monroy en el Estado de Hidalgo, México, 17, https://

[22] Young, “Diary,” 107.

[23] Rey L. Pratt, “A Latter-day Martyr.”

[24] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 9, 11.

[25] Guadalupe Monroy records Parra’s return to San Marcos as being 20 May 1917. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 41.

[26] “Reseña de la Vida de Jovita Monroy Mera” (typescript, 4 pages, n.d.), copy provided by Hugo Montoya Monroy, 1 March 2014, 2. Also, Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 42. (Consuela al joven Bernabé Parra citando las escrituras y diciendo, “Cuando hay tribulaciones es que Dios está más cerca de nosotros y quizá sea una prueba de Dios para nuestra fe)”.

[27] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 43.

[28] LaMond Tullis recounts the story of Trinidad Hernández in three sources, two of which are Mormons in Mexico, 110, 176–77; and “Los Primeros: Mexico’s Pioneer Saints,” Ensign, July 1997, 46–51. The third, “Cómo Llegó el Evangelio y el Libro de Mormón a México,” is the first in a series of lessons on the history of the Church in Mexico published at http://

[29] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 45. The desire to discount the authority of one of their own seems strange given that in the next generation many of the members in Mexico would be arguing that only their kind should be doing the ordinances and heading the administration of the Church, which would give rise to the separatist Third Convention movement. Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, chaps. 5–6.

[30] Monroy Mera, “Como llegó el Evangelio,” 46.

[31] Guadalupe Monroy (Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 46) notes that as of 1942, Isauro had not returned to the Church. However, Maclovia Monroy de Montoya and her daughter Minerva appended a note to Guadalupe’s record stating that “Isauro Monroy returned to the Church following the death of his last wife. While yet alive he attended the temple and remained faithful up to his death.” (Isauro Monroy volvió a la Iglesia después que su última esposa mueriera. En vida asistió al Templo y se mantuvo fiel hasta su muerte).

[32] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 45–46.

[33] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 46.

[34] Guadalupe Monroy lists the names of Juan Haro, Encarnación González, Amado Pérez Cano, Dimas Jiménez, Cándido Robles, Juan Mairet, Agustín Haro, Isaías Juárez, and Jesús Flores. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 47.

[35] Nadie se durmió en el tiempo que estuvo predicando. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 46–47. A short biographical sketch of Isaías Juárez may be found in Tullis, “Los Primeros: Mexico’s Pioneer Saints,” 46; and, in Spanish, Tullis, “Cómo Llegó el Evangelio.”

[36] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 47.

[37] Elena Parra Mera’s birth occurred in San Marcos in April 1921. Saunders Morales to LaMond Tullis, 11 February 2014. She grew up in the Monroy compound and enjoyed the educational advantages afforded all the Monroy and Mera children who had lived there. At age twenty-four (1945), she became the secretary-treasurer of the “Monroy school” that Bernabé Parra and Amalia Monroy had founded in San Marcos the previous year (Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 67). Eulalia Mera, Elena’s mother, later married Felipe Peña de Santiago Hidalgo with whom she had several children. She died 10 May 1985 in Santiago Tezontlale (Monroy Mera, “Como llegó el Evangelio,” 47), a place, like San Marcos, that continues with a resolute congregation of Mormons.

[38] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 47.

[39] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 51.

[40] As an example, consider the intense generational bonding that comes naturally for Mexicans but that for Anglo-Americans seems to require their presence in holy temples or preparing to be there. A symposium at Brigham Young University in 1977 addressed this and related issues associated with the expanding Church. See, in particular, the discussion on Latin America previewed by LaMond Tullis and addressed by Harold Brown, Orlando Rivera, Efraín Villalobos Vásquez, and Enrique Rittscher in Mormonism: A Faith for All Cultures, ed. F. LaMond Tullis (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), 85–150.

[41] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 47–48.

[42] Guadalupe Monroy states that in 1918 the men who attempted most diligently to keep the Church functioning in San Marcos and the gospel alive in people’s homes were Bernabé Parra (the branch president), Daniel Montoya, and Bernardino Villalobos. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 45.

[43] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 10.

[44] Daniel Montoya Gutiérrez, oral history, interview by Gordon Irving, 1974, typescript, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, 2.

[45] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 29–31.

[46] After a ten-year hiatus (1936–46), Páez was reconciled and returned with most of his flock of Third Conventionists to the Church. Bautista was never reconciled, fleeing to Ozumba where he founded his New Jerusalem settlement, which still functions long after his death. The Third Convention drama is reviewed in LaMond Tullis, “A Shepherd to Mexico’s Saints: Arwell L. Pierce and the Third Convention,” BYU Studies 37, no. 1 (1997–98); 127–157.

[47] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 47–48.

[48] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 53.

[49] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 53.

[50] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 53.

[51] Name provided by Minerva Montoya Monroy, email to LaMond Tullis, 21 September 2016.

[52] Lionel M. Summers, “The Divorce Laws of Mexico,” Journal of Law and Contemporary Problems, 310–11, http://

[53] Concubinato is discussed by Flavio Galván Rivera, “El Concubinato Actual en México,” https://

[54] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 52.