Introduction: Laboring in the Old Country

While serving as the first president of the Latter-day Saint Scandinavian Mission, Elder Erastus Snow initially relied on new converts to share the gospel. “I was there comparatively alone, and the harvest was great, and the laborers few, and the Spirit bore testimony that the Lord had much people there,” Snow recalled. “I cried unto the Lord, saying ‘O Lord, raise up laborers and send them into this harvest, men of their own tongue, who have been raised among them and are familiar with the spirits of the people.’” [1]

Elder Snow’s prayers were answered. By the time he returned to America in 1852, “there was quite a little army of Elders and Priests, Teachers and Deacons, laboring in the vineyard, and thousands [had] rejoiced in the testimony of the gospel borne to them by their fellow countrymen.”[2] Former shoemakers, carpenters, chimney sweepers, and men of other trades were transformed into powerful missionaries.[3] In many cases, these Scandinavian men were baptized one day and called on missions the next, oftentimes at great sacrifice. For instance, twenty-one-year-old Hans Christensen lost both his job and sweetheart and was ordered from his family home when he joined the Latter-day Saints, but he still served as a local missionary.[4] Historian William Mulder described these local missionaries and their proselyting efforts:

If standing up was construed as preaching, they preached sitting down; if religious services were forbidden in homes, they held “conversations”; if after imprisonment or court examination in one place they agreed not to proselyte, they went on to another and sent fresh laymen in their stead who had made no such promise. Where they were shut out as missionaries, they found work at their trades and passed the contagion of their message to fellow workmen. A shoemaker stuffed Mormon tracts into his customers’ shoes; a tailor sermonized as he sewed. They baptized by night along the river banks, and on the seashore. Every proselyte bore witness to his neighbor. The new gospel was germ which spread by contact. [5]

My own great-great-great-grandfather Peter Neilson Sr., a tailor by trade, served as a member missionary in Denmark. Born in 1813, he was taught by local missionaries and was baptized on 2 March 1853, by a local elder, A. Andersen. Shortly thereafter, Neilson was called to also labor as a local missionary. Although unseasoned in the faith, he endured persecution and boldly declared the gospel, before immigrating to Zion. “Before leaving my native land, I was laboring as a missionary in company with a young man, when one day, through misrepresentations of some wicked men, we were arrested as tramps and thieves and taken before the magistrate who said to us, ‘Are you not guilty of what these men accuse you?’ I replied that we were not,” Neilson wrote in his memoirs. “I then told him that we were preachers of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and bore my testimony to him of the restoration of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and while he did not believe my testimony, he told us to go home and draw up an affidavit of our social standing.”[6] Fortunately, he and his companion were released and allowed to resume proselyting. During the 1850s member missionaries like Neilson, “did not merely dominate . . . ; they were the scene, some of them serving six and seven years before emigrating.”[7]

In 1859, Ola N. Liljenquist became the first native Scandinavian elder to return to his old country to proselyte. “I was the first elder that had received the gospel in Scandinavia to return and testify of Zion. It was a wonder and a marvel to many who thought that no one could ever return after he got to the Rocky Mountains,” Liljenquist reported. “I went to the magistrate’s office [in Copenhagen] to report my arrival. All the officers and clerks left their chairs and desks and completely surrounded me and bid me hearty welcome. I spent a very agreeable time with them, testifying about Zion and my experience while I had been gone.”[8] Elders like Liljenquist helped accelerate baptism throughout the Scandinavian Mission.[9]

It wasn’t long before Latter-day Saint Scandinavian families relocated to the American West and sent a father or a son back to the old country as a missionary. For instance, two Swedish brothers wrote: “We have no desire to return to Sweden unless it is to preach the gospel.”[10] While these missionaries from Zion sacrificed much, they were greatly blessed. “In spite of hardships, the joys for the elder from Zion were many,” William Mulder explained.

It was satisfying to be a laborer in the Lord’s vineyard, to return to the Old Country an object of wonder in the eyes of former neighbors as a villager who had gone to America and made good. His return satisfied any longings for the old home he might have entertained and provided for the rest of the immigrants in Zion a vicarious outlet for nostalgic yearning—by pooling their funds to send him back and by exchanging frequent letters with him full of queries about friends and family in det gamle land, they made him their proxy. Going and returning was their living link with the past. And the arrival of Old World newspapers which he sent them, redeeming the isolation of Utah’s settlements informed them of European affairs, if only to make them glad they were in Zion. When the missionary came home, the community turned out to greet him with a choir or brass band, and heard a report of his labors at his “homecoming” in the meetinghouse.[11]

Peter Neilson was also numbered among those men favored to return to their native land as missionaries. During the 1879 October general conference, he was called on a proselyting mission to Scandinavia at age sixty-six. “I received intelligence that I had been called to a mission to my native land, Denmark,” he recorded. “The same day I preached my farewell discourse to them in our meeting house.” [12] After crossing America by rail and the Atlantic by ship, Neilson arrived in Denmark and was greeted by President Niels Wilhelmsen of the Scandinavian Mission. He was initially assigned to labor as a traveling elder in the Århus Branch, a town just north of his birthplace and home where he first met the missionaries in 1853. Within the day, he attended his first Sabbath meetings on Danish soil in almost twenty-four years and wasted no time before sharing his love of the gospel. “[I] attended Sunday School in the morning and in the afternoon meeting I had the privilege of talking to the people and bearing my testimony to the truth of the Gospel of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The same day I met one of my nephew, a brother’s [son], who was at the army and a sister,” he recorded. [13]

Peter Neilson’s arrival in the Scandinavian Mission was well timed. Within three weeks, Church leaders had organized the first regular Relief Society and Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association auxillaries in Scandinavia. The year, 1880, also marked fifty years since The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized and twenty-seven years since my ancestor was baptized. Although separated and removed from his family and loved ones in Utah, Neilson had found a temporary home—his native Denmark. His mission, however, was short-lived. “In August of this year, in consequence of my old age, being 67 years of age, I was released to return home,” he wrote. [14] After nearly a year’s absence from his family, Neilson reached his hometown of Washington, Washington County, Utah, in October 1880, where he was reunited with his family. While Neilson found it “satisfying to be a laborer in the Lord’s vineyard,” and “to return to the Old Country an object of wonder,” he also found it “sweet to be back again” surrounded by family and friends in the New World. [15]

By the end of the nineteenth century, 1,262 “elders from Zion,” like Neilson, had labored in the Scandinavian Mission. Not surprisingly, a Swedish official described his country as being “beleaguered by this missionary army from Utah.” [16] The Scandinavian Mission proved to be one of the most fruitful missions of the Church—even more successful than Great Britain in annual conversions.[17] As a result, thousands of Scandinavian converts immigrated to Zion.[18] A 1950 survey disclosed that nearly 45 percent of all Latter-day Saints had partial Scandinavian heritage. [19] Clearly, local member missionaries and elders from Zion impacted both individual seekers of truth throughout Scandinavia and the Church as a whole.

Passports to Paradise

Researchers have attempted to identify these local member missionaries who proselyted their countrymen before immigrating to Zion. They have also looked for those sent from Zion who later accepted one, two, or even three mission calls. Researchers generally reference biographical registers to answer specific questions about specific individuals. They agree facts are only significant in light of other facts. For example, discovering that your ancestor was born in Denmark, living in Ephraim when he received his mission call, and assigned to labor in Denmark is interesting; learning that your ancestor was a fifty-six-year-old high priest when he began his three-year mission to Norway is fascinating; however, knowing how your missionary’s demographics compare with those of his contemporaries is more enlightening and descriptive.

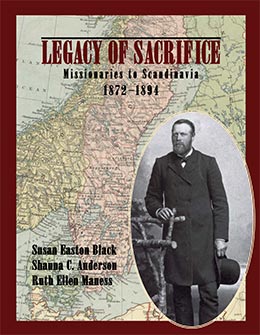

One of the most prominent researchers of the Scandinavian missionaries was assistant Church historian Andrew Jenson. He compiled a detailed biographical ledger, “Elders from Zion Who Labored in the Scandinavian Mission from 1850 to 1905.” [20] His larger database offers biographical data on 1,262 returning Scandinavian missionaries, from 1850 to 1899. Augmenting this database is Legacy of Sacrifice: Missionaries to Scandinavia, 1872–1894, authored by Susan Easton Black, Shauna C. Anderson, and Ruth Ellen Maness. This text provides a biographical sketch on approximately 520 Scandinavian missionaries who returned to America via Copenhagen, 1872–94. The authors have contacted descendants and conducted extensive research on these missionaries to obtain as accurate information as possible. In addition, stories have been collected that describe their life struggles, hardships, and dedication to the Church. These biographies are truly inspiring and provide information for those doing family history research. In a previous publication, Passport to Paradise: The Copenhagen “Mormon” Lists, 1872–1894, vols. 1–2 (West Jordan, Utah: Genealogical Services, 2000), Shauna C. Anderson, Ruth Ellen Maness, and Susan Easton Black list approximately 14,500 Latter-day Saints who migrated from Scandinavia and Germany to America, via Copenhagen, Denmark, from 1872 to 1894. This exhaustive study also catalogs the names, ages, marital status, family relationships, places of residence, and ships of each emigrant. The emigrants’ ships, European departure dates, United States arrival dates, and company entrance dates into the Salt Lake Valley are detailed. In addition, European maps and pictures of the emigrants’ ships are provided. Names of the missionaries found in this publication were also found on those records.

Together, these publications provide priceless resources for those investigating the nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint Church in Europe.

As a result, the following questions can be answered. What was the national heritage of the missionaries? Where were they residing when they received their missionary calls? Where were they assigned to labor in Scandinavia? How old were they when they began their Scandinavian missionary service? What priesthood office did they hold? How long did they serve in Scandinavia? Did any of them die while serving in the Scandinavian Mission? While statistics do not tell the full story, they do provide important contrasts.

Scandinavian Mission Statistics, 1850–99

What was the national heritage of these nineteenth-century missionaries called to the Scandinavian Mission? Exactly 494 missionaries, or 39.5 percent of the entire Scandinavian Mission population, were of Danish birth. Sweden contributed 384, or 30.7 percent of the missionary force, while the United States and Norway contributed 237, or 18.9 percent, and 121, or 9.7 percent, respectively. In other words, nearly 80 percent of the missionary force was of Scandinavian birth.

Where were these elders residing when they received their missionary calls? Not surprisingly, the majority of elders were living in Utah. For the first fifteen years, the Salt Lake region contributed the most missionaries to the Scandinavian Mission. However, beginning in 1865 and continuing until 1899, the central and south central regions of Utah, together with Salt Lake, produced the majority of Scandinavian elders. The central area included the counties of Duchesne, Tooele, Uintah, Utah, and Wasatch, and the south central region included the counties of Carbon, Emery, Grand, Juab, Millard, Sanpete, and Sevier. The south central region contributed the most missionaries to the Scandinavian Mission during the nineteenth century.

Where were the missionaries assigned to labor in Scandinavia? From 1850 until 1905, the Scandinavian Mission was responsible for Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Leaders also sent elders to Iceland, Finland, Russia, Switzerland, and Germany.[21] Between 1850 and 1899, 535, or 42.9 percent of the elders, were assigned to labor solely in Denmark. [22] A total of 446, or 35.7 percent of the missionaries, were assigned to Sweden, and 178, or 14.3 percent, to Norway. From 1850 until the time period of 1895–99, Denmark had the largest missionary force. However, Sweden held a close second. Between the years 1895–99, Sweden actually surpassed Denmark in missionary numbers. After the first five years of the mission, neighboring Norway still hadn’t reached half of the resources of Sweden or Denmark. Most missionaries served in several cities of the same country but 80, or 6.4 percent of the elders, served in two or more countries.

The missionaries’ heritage and language skills seem to be the determining factor for their assignment throughout the world, particularly within Scandinavia. “Practicality dictated . . . that Scandinavian-born elders, familiar with their native language and culture be returned to Scandinavia, a policy that made theological sense as well,” Rex Price explained. “If the sons of Ephraim were literally linked to Hebraic bloodlines, they would be so through their parents, grandparents, etc. If the elders had responded to the gospel sound, it was possible that their relatives would also.” [23] According to Price, of the 855 Scandinavian-born elders who served missions worldwide between 1860 and 1894, 692, or 80 percent, were called to return and labor in the Scandinavian Mission.[24] Scandinavian elders were generally assigned to labor in their country of heritage. Of the 492 Danish-born elders, 421, or 85.6 percent, were assigned to Denmark; of the 383 Swedish-born elders, 343, or 89.6 percent, were assigned to Sweden; of the 121 Norwegian-born elders, 95, or 78.5 percent, were assigned to Norway. The 237 American-born missionaries seem to be randomly assigned across Scandinavia: 37.6 percent served in Denmark, 33.8 percent in Sweden, and 22.4 percent in Norway, while the remainder served in a combination of countries.

How old were the missionaries when they began their Scandinavian missionary service? Unlike today’s missionary force which generally ranges between nineteen and twenty-six years of age, as a whole the Scandinavian missionaries were older. Gideon E. Olson Jr. was the youngest missionary to labor in the Scandinavian Mission. He was born on 19 December 1879, in Paradise, Utah. Olson was called to Scandinavia at the age of eighteen. He arrived in the mission field on 9 October 1897, and returned to Utah on 30 November 1899. Soren C. Thure was the oldest missionary to serve in the Scandinavian Mission. He was born on 17 December 1796, at Harrisdslev, Denmark. Thure was baptized on 28 January 1856, at the age of fifty-nine. He immigrated to Utah six years later and was called at the age of seventy-four to labor in the Scandinavian Mission. He arrived in Demark on 5 June 1870 and served until 1 September 1871, when he departed for America.

Between 1850 and 1899, the mode age was 34 and the average was 38.6 years, based on the figure of 1,252 missionaries. During about the same period, the worldwide missionary mode age was 22 and the average age, 35.6 years, based on 1,030 missionaries worldwide. [25] The average mission age fluctuated between a low of 32.4 years during 1860–64 and a high of 41.8 years during 1870–74. By the end of the nineteenth century (1895–99), the average mission age had decreased to 36.4 years. Several factors may be responsible for the decline. First, the overall mission age declined due to the federal prosecution of polygamist heads of families and the growing number of older brethren hiding in the Mormon underground.[26] Second, “the initial pool of converts to Mormonism had steadily declined from earlier days and second generation elders, many of whom were presumably not skilled in the language, were needed to man these missions.” [27] Third, Church leaders seemingly believed that younger men could learn foreign languages like Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian easier than their senior counterparts. [28]

Although the average mission age of the elders was declining after a high in 1870–74, elders were probably more mature in the gospel than their predecessors. Church age, or the number of years from baptism to missionary service, almost doubled. From 1850 to 1854, the average Church age was 11.2, years and from 1895 to 1899 it was 21 years. Correspondingly, the average baptismal age dropped significantly from 25.4 years in 1850–54 to 15.5 years in 1895–99 due to an increasing number of Utah-born missionaries. Clearly, younger second-generation Latter-day Saint men arrived in Scandinavia with more Church experience than their predecessors.

What priesthood office did these missionaries hold? The priesthood is divided into the lesser, or Aaronic, and the higher, or Melchizedek, priesthoods. Both the lesser and greater priesthoods are further divided into several offices whose members met together in quorums. For example, the Melchizedek Priesthood is composed of elders, high priests, and the Seventy (regardless of priesthood quorum, all male missionaries were referred to as “elder”). Revelation dictated that of these quorums, the Seventy were expected to focus on missionary work in the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1855–59, the quorums of the Seventy carried the Scandinavian Mission. Between 1880 and 1884, the number of quorums of the Seventy reached its low point in representation at 47.1 percent. From the year 1890 to 1894, they represented 95.4 percent of all missionaries in Scandinavia. Seventies comprised 83.3 percent of the entire missionary force in nineteenth-century Scandinavia. Truly, “the elders of Israel were, in fact, the seventies of Israel,” particularly in the Scandinavian Mission.[29] Elders, at their height, contributed only 36.3 percent of the missionary force; high priests never contributed more than 20 percent after 1850–54.

How long did these men serve in Scandinavia? Between 1850 and 1899, the average Scandinavian missionary served for 21.3 months, or 1.8 years—shorter than their modern counterparts’ 24 months. During the same period, the average worldwide mission duration was 24 months. [30] In the years 1850–54, the average mission duration was at its highest at 26.6 months. It reached its lowest in 1855–59 at 17.1 months. This was possibly due to elders being recalled to Zion during the Utah War. Beginning in 1870–74, there seems to be a strong correlation between mission age and mission duration—the younger the missionary, the longer the mission. Perhaps leaders expected their young men to shoulder more responsibility. Also, these younger brethren likely had smaller families, if any, and could afford to remain in the mission field longer than their older counterparts.

While the average mission duration in the Scandinavian Mission was 1.8 years, there were some notable exceptions. For example, the missionary serving the longest mission was Arne C. Grue, who served for 5.1 years. Grue was born in Norway and was baptized in 1859. He immigrated to Utah several years later after working as a watchmaker. At the age of thirty-five, he received his mission call and arrived in Denmark on 31 July 1867. For the next five years, Grue labored as a traveling elder in Norway and presided over the Jönköping Conference, Sweden. He embarked for Utah on 30 August 1872. One of the shortest and most unique missions was that of Janne M. Sjodahl. Sjodahl was born on 29 November 1853 in Karlshamn, Sweden. In 1886, he immigrated to Utah, where he was baptized on 7 October 1886. Between 1886 and 1887, he translated the Doctrine and Covenants into Swedish. In 1897, Church leaders called him to present a copy of the Swedish Book of Mormon to King Oscar II for His Majesty’s twenty-fifth-year Swedish jubilee on behalf of the Scandinavians living in Utah. At the age of forty-three, Sjodahl arrived in Scandinavia on 5 September 1897, and on 22 September, presented the volume to the Swedish king. He departed for America eight days later, having spent less than one month in Scandinavia.

Did any missionaries die while serving in the Scandinavian Mission? Sadly, seven missionaries’ lives and missions were cut short. Willard Snow, Elder Erastus Snow’s brother and acting mission president, was attacked by an “evil power” and finally passed away in August 1853. [31] President Niels Wilhelmsen died in Copenhagen in August 1881 after a hospital operation. [32] In June 1887, Jasper Petersen passed away at Odense, Denmark, after fighting chills and fevers. [33] Andrew K. Andersen, president of the Ålborg Conference, died in January 1890, of “lung trouble” after only a few days of sickness. [34] In August 1893, Pehr A. Bjorklund, a missionary in the Skåne Conference, Sweden, died at Hälsingborg, Sweden, of a “rupture.” [35] Anders Bjorkman, a missionary in the Stockholm Conference, Sweden, expired in August 1896, while helping harvest a field. [36] Lastly, Albert Peterson passed away at Uppsala, Sweden, in December 1898, at the tender age of twenty-six after leaving his new bride in Utah for missionary service. [37]

Thus, the “typical” missionary from Zion would have been born in Denmark and likely converted as a boy or young man before immigrating with this family to Zion. He would have settled in one of the Scandinavian communities of Sanpete, Sevier, or Salt Lake counties. At about age thirty-eight, after being set apart as a Seventy, he would have been called back to Denmark to serve as a missionary. While in Denmark, he would have served as a laboring missionary and then have been called as a branch or conference president until he was released after 1.8 years of dedicated service. Most of these missionaries would have experienced much hardship and persecution while serving. While away from home, their families would have also sacrificed their means to support them. These missionaries and their families have left their “legacy of sacrifice,” which has benefited and will continue to benefit many of their descendants.

Notes

[1] Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1972 (chronological scrapbook of typed entries and newspaper clippings, 1830–present), September 18, 1859, Church Archives, as quoted in William Mulder, Homeward to Zion: The Mormon Migration from Scandinavia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1957), 48.

[2] Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, September 18, 1859, Church Archives, as quoted in Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 48.

[3] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 48.

[4] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 48.

[5] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 51.

[6] Reid L. Neilson, Peter Neilson Sr: A Life of Consecration (Provo, UT: Community Press, 1997), 26–27.

[7] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 55.

[8] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 57.

[9] Jennie C. Mortensen was the only sister missionary set apart to serve in the Scandinavian Mission during the nineteenth century. She was born 26 June 1865 as Paris, Bear Lake County, Idaho, and was single and residing in Salt Lake City when she was called on a mission at the age of thirty-four. She arrived in Denmark on 27 August 1899 and served faithfully for one year.

[10] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 56–57.

[11] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 62.

[12] Neilson, Peter Neilson Sr, 125.

[13] Neilson, Peter Neilson Sr, 128.

[14] Neilson, Peter Neilson Sr, 131.

[15] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 62.

[16] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 56.

[17] Mulder, Homeward to Zion, 31.

[18] William R. Merriam, director, Census Reports Volume 1: Twelfth Census of the United States, Taken in the Year 1900–Population Part 1 (Washington DC: United States Census Office, 1901), 789–90. According to the 1900 United States Census, there were 4,924 foreign-born U.S. citizens living in Utah. Of this number, 513 were from Denmark, 204 were from Norway, and 552 were from Sweden, making 25.7 percent (1,259) of the foreign-born Utah population Scandinavian.

[19] John Langeland, “The Church in Scandinavia,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1262–65.

[20] Andrew Jenson, Missionaries Who Labored in the Scandinavian Mission from 1850 to 1905, Church Archives, Salt Lake City. Jenson’s team painstakingly recorded each of the missionaries’ information on 8 ½-by-14-inch, hand-ruled paper. For each missionary they included as variables: number, meaning chronological order of the missionary at arrival in the Scandinavian Mission; name, meaning missionary’s full name; priesthood, meaning priesthood office held at arrival in the Scandinavian Mission; arrival at Copenhagen, meaning MM/

[21] Iceland was considered part of the Scandinavian Mission from 1851 until 1894, when it added to the British Mission.

[22] Denmark statistics include missionaries who served in the Scandinavian Mission office located in Copenhagen, Denmark, while they presided over the mission, or were involved with the mission’s translation and publication efforts.

[23] Rex Thomas Price Jr., “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1991), 91.

[24] Price, “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century,” 92.

[25] William E. Hughes, “A Profile of the Missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1849–1900” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1986), 133.

[26] Price, “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century,” 102. These same polygamous heads of families may also have been called to serve in Scandinavia to protect them from federal prosecution.

[27] Price, “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century,” 102.

[28] For a more detailed analysis of thoughts of early Church leaders on language ability, see Price, “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century,” 102–7.

[29] Price, “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century,” 113. See also James N. Baumgarten, “The Role and Function of the Seventy in Church History” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1960).

[30] Hughes, “A Profile of the Missionaries,” 151.

[31] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 82.

[32] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 256–57.

[33] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 301–2.

[34] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 313.

[35] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 331.

[36] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 350.

[37] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 367.