The Smithsonian Sunstone: An Iconic Nauvoo Temple Relic

Alexander L. Baugh

Alexander L. Baugh, “The Smithsonian Sunstone: An Iconic Nauvoo Temple Relic,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 85‒114.

Alexander L. Baugh was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

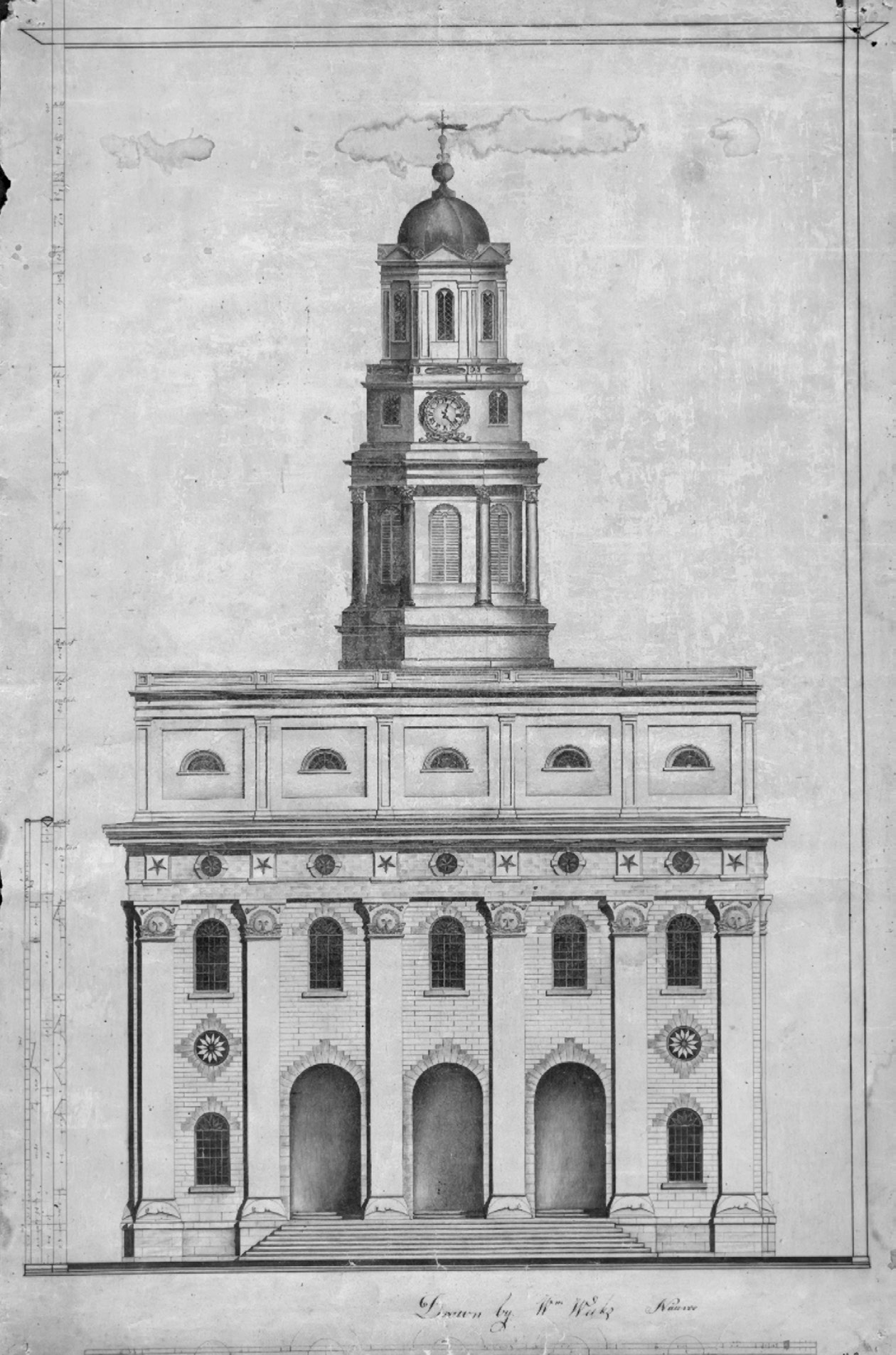

William Weeks’s architectural drawing of the west wall of the original Nauvoo Temple. Church History Library.

William Weeks’s architectural drawing of the west wall of the original Nauvoo Temple. Church History Library.

Visitors to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, will find thousands of artifacts of every type and description on display, each of which is associated with a variety of historical themes—pop culture, business, politics, exploration, transportation, innovation, and religion, among many others. It’s America’s premier historical museum and draws millions of visitors each year. On the main floor in the “American Stories” exhibition is a rather unusual artifact—a capital sunstone from the original Latter-day Saint temple in Nauvoo, Illinois, constructed between 1841 and 1846—one of only two complete sunstones in existence.

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist and at one time the Smithsonian’s Distinguished Scholar and Ambassador-at-Large, included a feature story about the sunstone and the Latter-day Saints in his book The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects. Concerning this unique symbolic historical object, Kurin wrote, “It is among the most important relics to survive from the Mormon Temple, a site that played an important role in the religion of the Latter-day Saints.”[1] Every historical artifact has a unique story and a history all its own, and the Smithsonian Nauvoo Temple sunstone is no exception.

Nauvoo Temple Architectural Drawings and Descriptions

In late August or early September 1840, a year after the Latter-day Saints had first begun to settle Commerce (later Nauvoo), Illinois, Joseph Smith formally announced to the Saints that they were to move forward with plans to construct a temple.[2] About this same time, William Weeks, an experienced builder who had some knowledge and architectural training in the Greek Revival style, was selected to be the architect and general superintendent for the building.[3]

A revelation received by Joseph Smith in January 1841 indicated that he would receive revelatory knowledge regarding “all things that pertain to this house.”[4] This not only included an understanding of the sacred ordinances that would make up the temple’s rituals but also encompassed an understanding of the temple’s overall appearance and ornamental design, which Smith said he had received from a heavenly vision. For example, on 5 February 1844, Weeks met with the Prophet to discuss the type of windows that he was proposing be used in the half-story “office space” floor that separated the lower hall from the upper hall of the temple. Smith proposed having circular exterior windows, but Weeks objected, saying that a circular window went against the known rules of architecture for a building of that size and height. Smith replied, “I wish you to carry out my designs. I have seen in vision the splendid appearance of that building illuminated and will have it built according to the pattern shewn [shown] me.”[5]

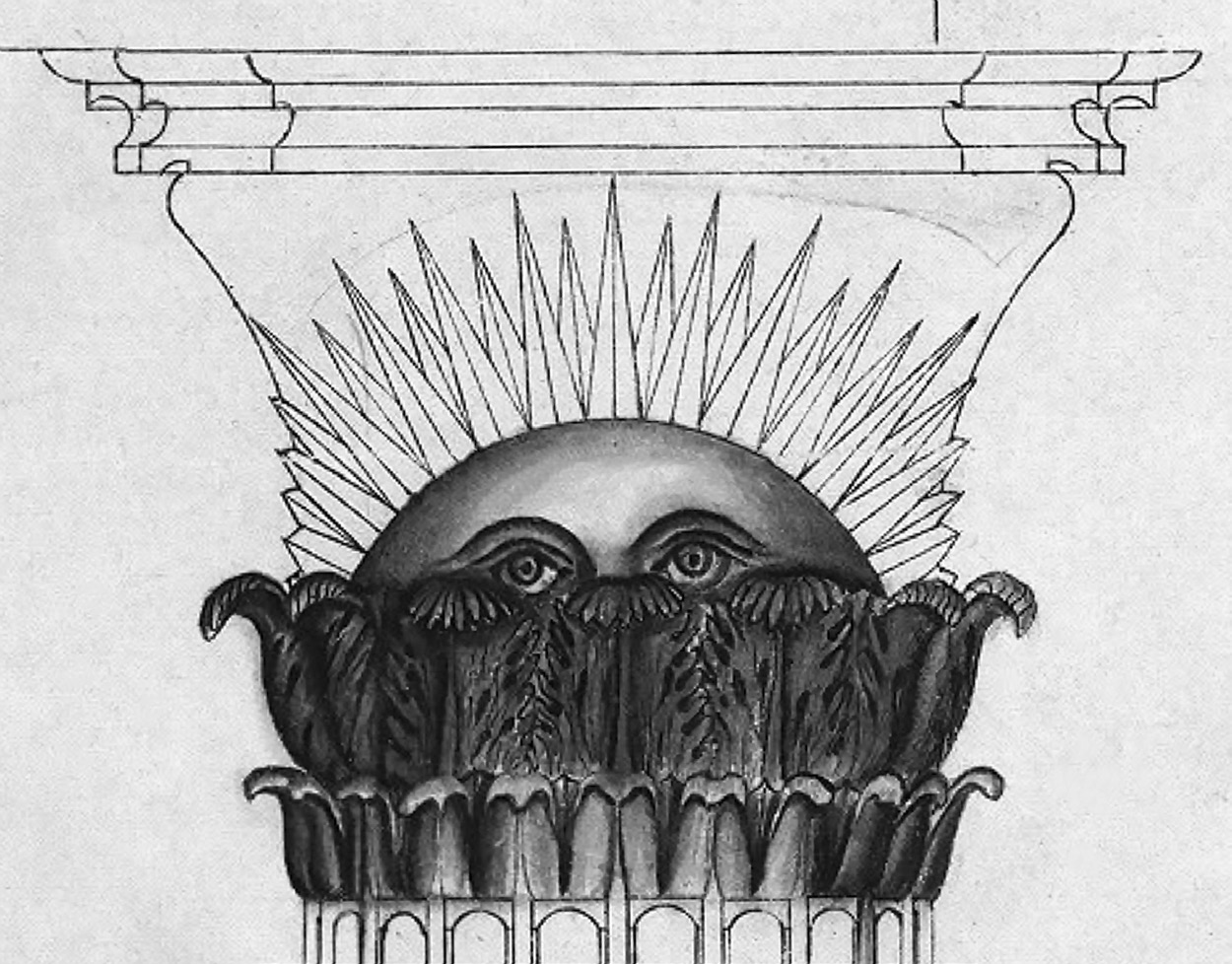

Figure 1. Portion of an early drawing by William Weeks of a Nauvoo capital sunstone, circa 1841–46. Church History Library.

Figure 1. Portion of an early drawing by William Weeks of a Nauvoo capital sunstone, circa 1841–46. Church History Library.

Figure 2. Portion of what was likely the final architectural drawing by William Weeks of the front of the Nauvoo Temple showing two “full-faced” sunstone capitals on the pilaster, circa 1841–46. Church History Library

Figure 2. Portion of what was likely the final architectural drawing by William Weeks of the front of the Nauvoo Temple showing two “full-faced” sunstone capitals on the pilaster, circa 1841–46. Church History Library

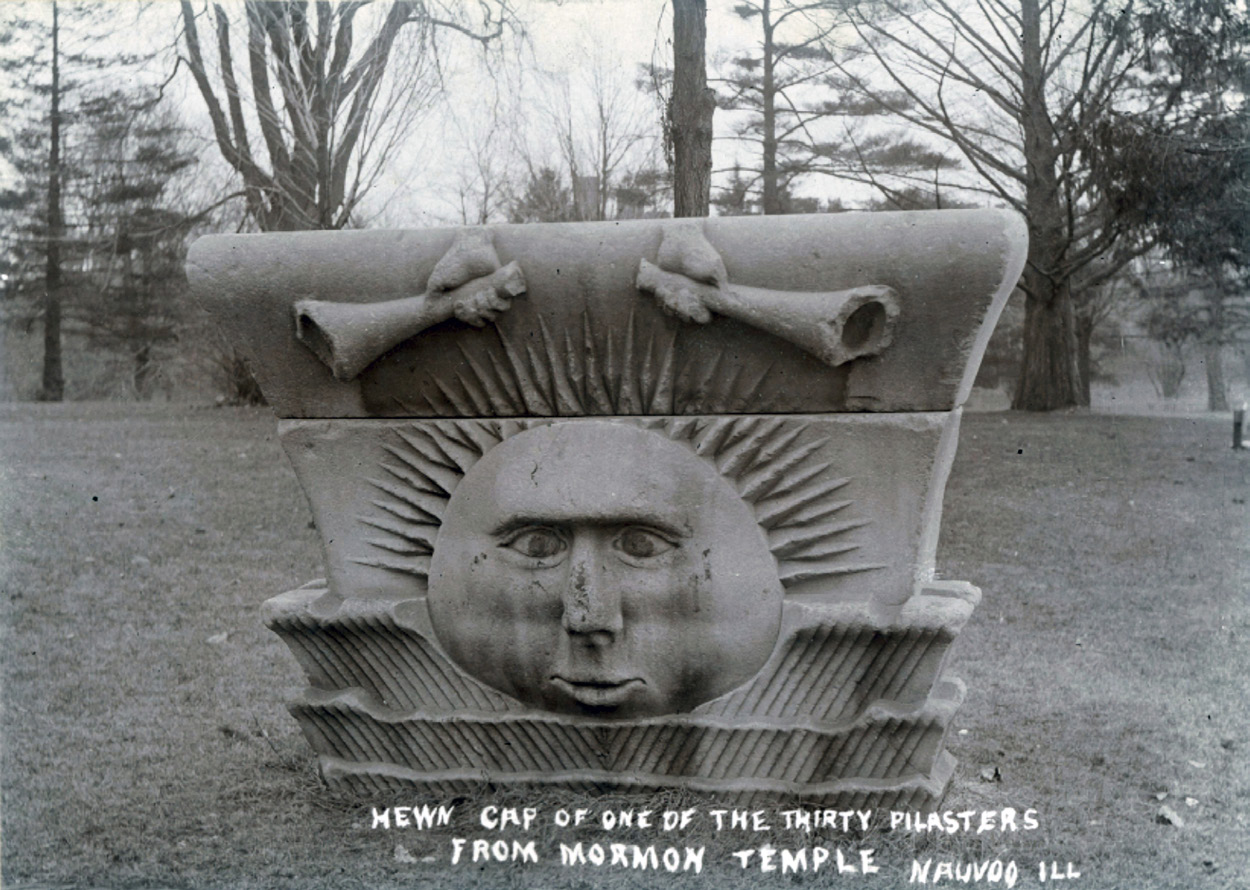

Unfortunately, only a small portion of Weeks’s Nauvoo Temple architectural drawings have survived. These include two different full depictions of the temple’s west (front) exterior wall—an earlier rendition and the final one—along with fourteen fragments of various sizes containing a number of preliminary sketches. An examination of these drawings, along with several early photographic images (daguerreotypes and tintypes), and some of the remnant ornamental stones of the completed temple, illustrates that Weeks made changes and modifications in the temple’s design during the construction. Architectural drawings of the capital sunstones are a good example. One of Weeks’s early detailed drawings of a capital stone shows a singular sunburst with a human-like face that is almost completely obscured by acanthus leaves (figure 1).[6] In contrast, Weeks’s final architectural rendering of the temple’s front facade (i.e., west wall) includes a less detailed illustration of six capital stones, each depicted with a full-facial sunburst figure rising from a representation of clouds. Also included above each sunburst are two hands, each holding a trumpet (see figure 2).[7] Brigham Young’s description of the finished capitals aligns closely with Weeks’s final drawings as well as with close-up photographic images of the completed temple. Young wrote that each capital consisted of “one base stone, one large stone representing the sun rising just about the clouds, the lower part obscured; the third stone represents two hands each holding a trumpet, and the last two stones form a cap over the trumpet stone, and these all form the capital.”[8] No full-scale architectural drawings of the temple’s east wall exist; however, it featured six sunstones, just like the west-facing front wall. Photographic images of the south wall of the completed temple show nine sunstones; the north wall had the same number. In total, there would have been thirty sunstones—six each on the front and back walls, and nine each on the north and south walls (see figure 3).

Temple Construction—Carving the Sunstone Capitals

Figure 3. Louis Rice Chaffin daguerreotype copy of an earlier daguerreotype of the original Nauvoo Temple, circa 1847. The image shows a full view of the south wall of the temple and an obscured view of the front west wall. Church History Library.

Figure 3. Louis Rice Chaffin daguerreotype copy of an earlier daguerreotype of the original Nauvoo Temple, circa 1847. The image shows a full view of the south wall of the temple and an obscured view of the front west wall. Church History Library.

Groundbreaking ceremonies for the temple took place on 6 April 1841. Thereafter construction on the main structure proceeded as funds and labor (both paid and donated labor) became available and as weather permitted. Because of winter conditions, most actual construction on the temple walls ceased in December and resumed in March, although stonecutters worked during the winter months by quarrying the limestone and rough-cutting the blocks.

By late 1842, some eighteen months after construction began, the temple’s foundation walls had been completed, and the outside walls reached to the bottom of where the windowsills would be.[9] This would indicate that at least some of the thirty moonstones, which formed the base of each capital pilaster, would also have been set in place (see figure 4).[10] At the time of the April 1843 general conference, the outside walls were between four and twelve feet high.[11] Five months later (in August 1843), David Nye White, a Philadelphia newspaper reporter, visited Nauvoo and reported that the walls of the temple were between fifteen and eighteen feet in height.[12] However, it would take another thirteen months before the temple walls were high enough so that the capital sunstones could be set in place.

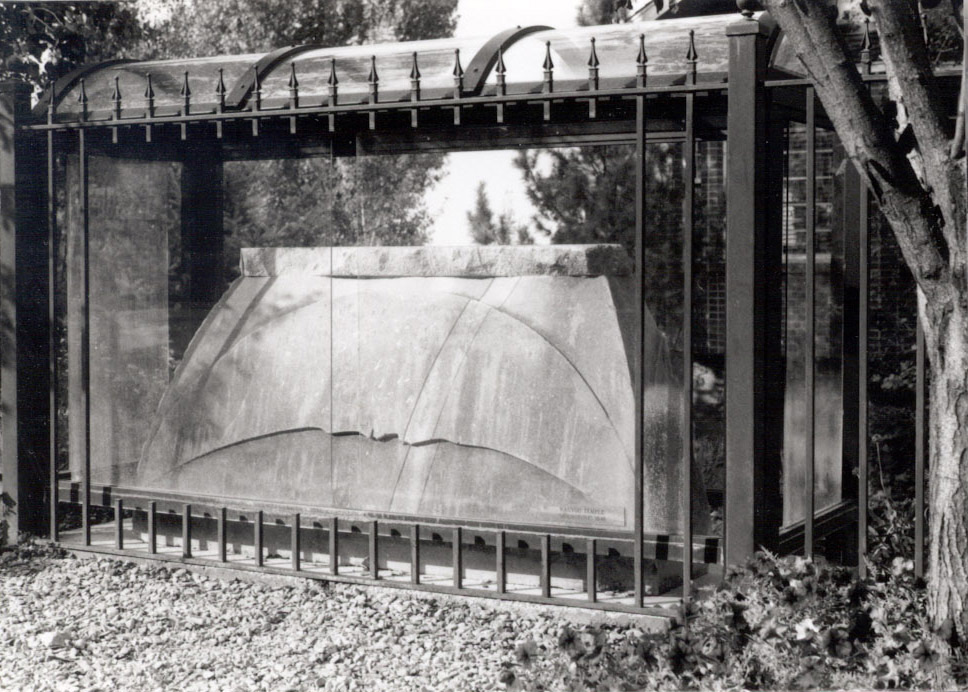

Figure 4. Original moonstone from the Nauvoo Temple located for many years on the home property of Blake T. Roney, Provo, Utah. The stone is one of only two complete original moonstones. The stone is currently in the possession of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Photograph by author, 1998.

Figure 4. Original moonstone from the Nauvoo Temple located for many years on the home property of Blake T. Roney, Provo, Utah. The stone is one of only two complete original moonstones. The stone is currently in the possession of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Photograph by author, 1998.

Beginning in March 1844, the more experienced and skilled stonecutters began the more detailed, intricate work of shaping the capital sunstones. That same month, Charles Lambert, a Latter-day Saint convert from Yorkshire, England, and a highly skilled stone carver, arrived in Nauvoo. It did not take long for the temple foremen to recognize his proficiency and mastery of the craft and set him to work carving the capitals. “I worked and finished the first capital,” he wrote. He also assisted in sculpting eleven others, the most of any of those who are known to have worked on the temple sunstones.[13] Benjamin T. Mitchell, another highly skilled stone carver, is also credited with sculpting the first sunstone, in addition to three other capitals.[14] Given the nature of the craft, both Lambert and Mitchell may have collaborated or assisted each other in fashioning the first capital.

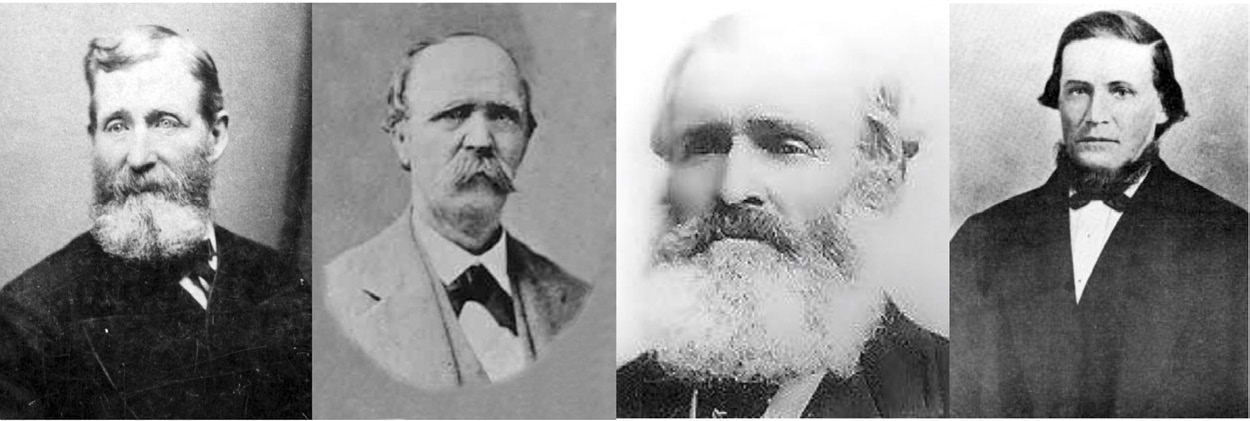

An entry in a Nauvoo Temple committee account book gives the names of four other highly skilled stone carvers who sculpted all or some portion of a number of sunstones—namely, Harvey Stanley, John Harper, James Sharp, and Rufus Allen. The account ledger indicates that each of these carvers were compensated proportionate to the work they did on a particular stone, which amount could be used to purchase food, commodities, and merchandise that had been donated or appropriated to the temple fund from tithing contributions, or other types of donations given to the fund by Church members. For example, Harvey Stanley was credited $300 for carving an entire sunstone, $150 for carving part of another, $75 for assisting Rufus Allen, and another $5 for assisting James Sharp with their carvings. Sharp assisted Lambert and Stanley on a sunstone and received $10 credit, and then received an additional $5 credit for moving a sunstone from the south side of the temple to the north side and resetting the stone.[15] Another carver whose name does not appear in the account book is James Henry Rollins, who learned to cut stone as an apprentice under Harvey Stanley. Eventually, Rollins was able to work on his own and cut stones for the pilasters and archways. Later, Mitchell, Lambert, and another stone carver asked Rollins to “rough out” three capital stones, which he did. Finally, William Weeks, the temple architect, and William Player, the chief “stone setter” who mortared the stones in place, requested that Rollins dress one of the capital stones. “I told them I didn’t think I was capable of cutting one of those stones,” Rollins said, “but they persuaded me to try it and they would help me out.” He then added, “I did so with reluctance, but accomplished this task.” Rollins further noted that his sunstone was placed on the northeast corner of the north wall (figure 5).[16]

Figure 5. Individuals who are known to have worked as stone carvers on the Nauvoo Temple capital sunstones. Left to right: Charles Lambert, Benjamin T. Mitchell, Rufus Allen, and James Henry Rollins. Church History Library.

Figure 5. Individuals who are known to have worked as stone carvers on the Nauvoo Temple capital sunstones. Left to right: Charles Lambert, Benjamin T. Mitchell, Rufus Allen, and James Henry Rollins. Church History Library.

On 15 May 1844, Josiah Quincy and Charles Francis Adams, prominent residents of Boston who were sightseeing in the West, spent much of the day visiting with Joseph Smith in Nauvoo, part of which included an afternoon visit to the temple grounds. At the construction site, they passed one of the stone carvers working on the face of a sunstone. At the time, it had only been about two months since the carvers had begun sculpting the capitals, so this was likely one of the first to be fashioned. Upon seeing the Prophet and his guests, the worker stopped chiseling, looked up, and asked, “Is this like the face you saw in vision?” Smith replied, “Very near it, . . . except that the nose is just a thought too broad.” Quincy was impressed with the yet uncompleted building, calling it “striking” and a “wonderful structure,” but considered the sunstones and moonstones “queer carvings.”[17]

Setting the Capital Sunstones

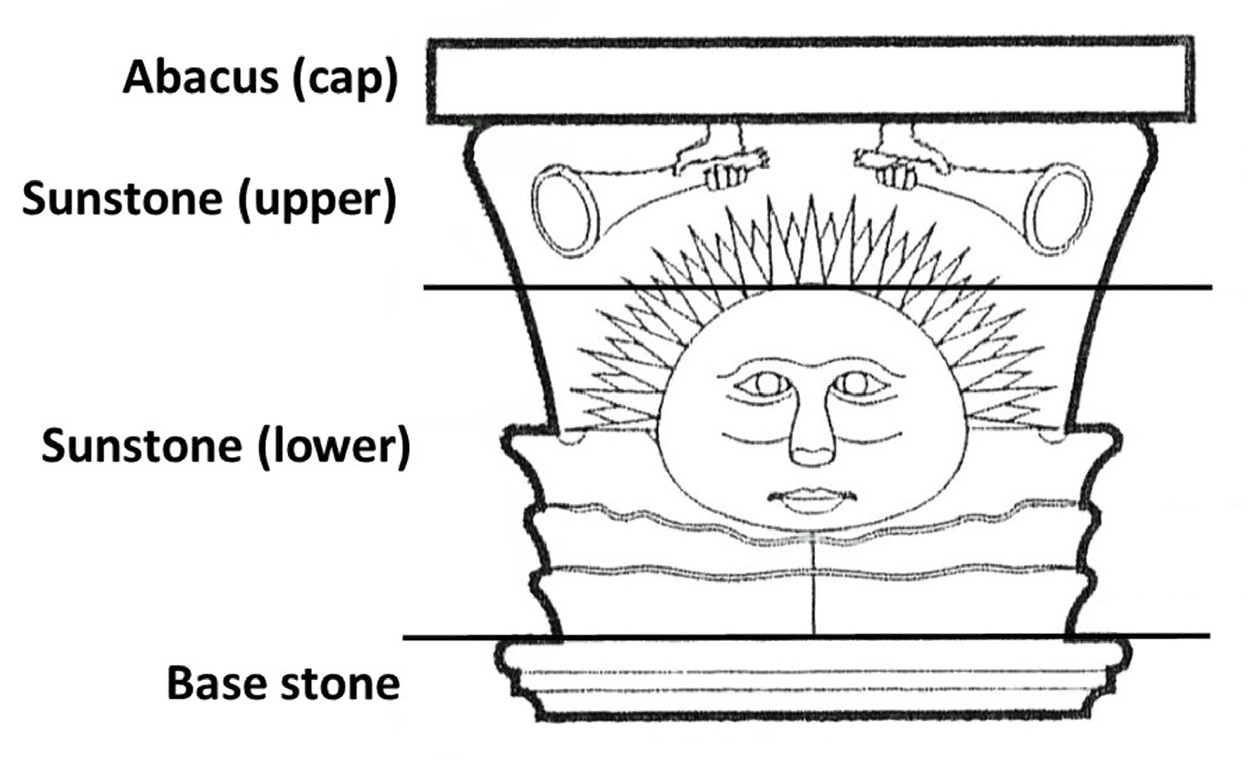

By late September 1844, the outside temple walls—including the capital pilasters—were approximately forty-four feet from the ground and high enough to begin setting the actual capitals.[18] As noted, each capital sunstone consisted of four parts: (1) the base stone; (2) the lower portion of the sunstone, which included the clouds, the sun’s face, and the side portion of the sunburst; (3) the top portion of the sunburst and the trumpet stones; and (4) the abacus stone, or the block or “cap” that was set over the trumpet stone (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Diagram showing the sections that composed the sunstone capital.

Figure 6. Diagram showing the sections that composed the sunstone capital.

Both the upper and lower sections of each sunstone appear to have been carved as separate stones, although it is possible that the entire sunstone was shaped from one complete block of stone and then cut. Regardless, the likely reason the sunstone was in two separate pieces was to facilitate hoisting lighter, less cumbersome stones to their positions on the pilasters, rather than trying to lift entire stones that would have been much larger and heavier. Using a crane and pulley system, workers winched the base stone to the top of the pilaster, where it was mortared into place and left to fully cure. With that process completed, the sunstone could be hoisted and cemented onto the base stone. First, the lower section (the clouds and the sun’s face) was fixed to the base stone, then the smaller top section (upper portion of the sunburst and the trumpets) was mortared or “attached” to the lower section, and finally, the abacus stone (the top block or cap) was added, thus completing the setting.

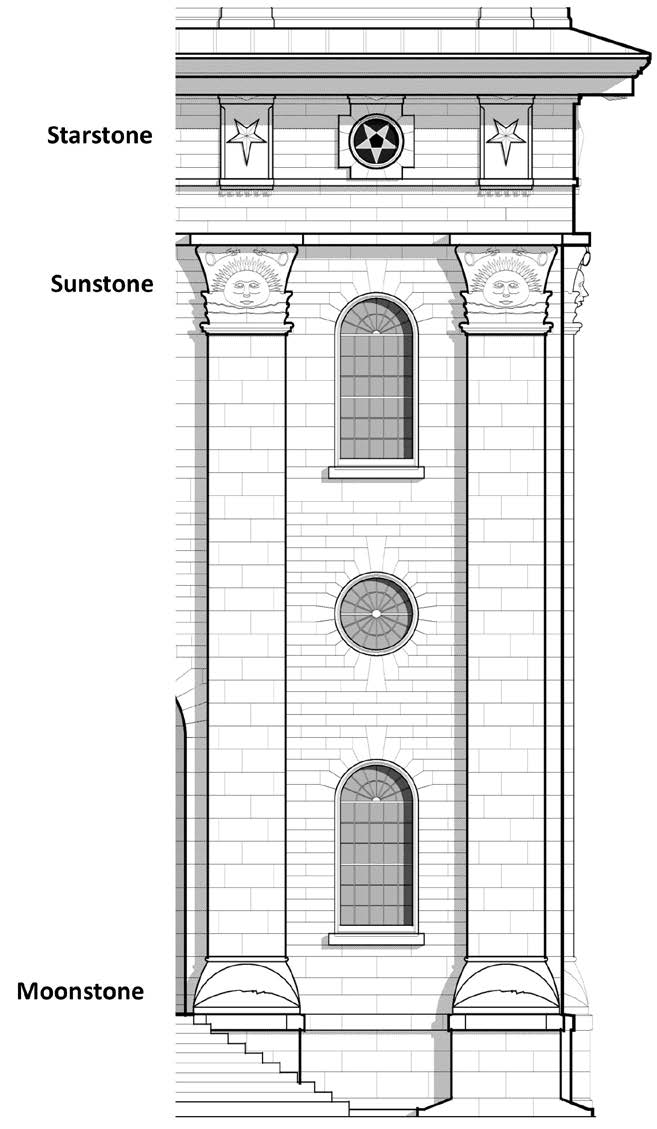

Figure 7. Portion of an architectural drawing of the Nauvoo Temple showing the position of the decorative sun, moon, and starstones. The stones were meant to represent the imagery in Revelation 12:1. “And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars.” Roger P. Jackson, FFKR Architects, Salt Lake City.

Figure 7. Portion of an architectural drawing of the Nauvoo Temple showing the position of the decorative sun, moon, and starstones. The stones were meant to represent the imagery in Revelation 12:1. “And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars.” Roger P. Jackson, FFKR Architects, Salt Lake City.

Workers installed the first capital sunstone on 23 September 1844, but it was not without incident. The crew working the crane from the top succeeded in raising the stone to where it was to be set, but while attempting to draw it to the wall, a portion of the crane gave way due to the stone’s weight. It was only by “great care,” William Clayton wrote, that “the stone was safely landed and set without further accident.”[19] Two days later, as the workers attempted to raise the second capital, the entire crane fell from the top of the wall, falling within a foot of one of the workers on the ground. It was several days before the crane was repaired and work could proceed again.[20] By 1 October, six additional capitals had been raised and set into place, bringing the total to seven.[21] During the next two months, the work of setting the capitals progressed slowly because of bad weather and because the carvers had not completed their cuttings on the remainder of the capitals. On 6 December, the last capital was set in place, although Clayton indicated that twelve of the capitals did not include the trumpet stones. He then noted that they would be set in place the following spring.[22] Nonetheless, the “near-completion” of the placement of the capitals marked a milestone in the temple’s construction.

It took crews another eighteen months to finish the top portion of the upper hall, the attic, the clock and bell tower, and the interior. By this time, Brigham Young and most of the members of the Twelve had permanently left Nauvoo and were making their way across southern Iowa. Young left the formal public dedication of the temple, held on 1 May 1846, to Elder Orson Hyde—a member of the Twelve still in Nauvoo—whose dedication marked the building’s official completion.

Nauvoo Temple Symbolism

Situated a few feet above each of the thirty capital sunstones was an inverted star stone, which completed the three major exterior symbolic carvings—the moonstone at the base of the pilaster, the sunstone capital, and the star stone above the capital. Some have assumed that the sun, moon, and star motifs of the Nauvoo Temple represented the three degrees of eternal glory as given in section 76 of the Doctrine and Covenants—the sun (celestial kingdom), moon (terrestrial kingdom), and the stars (telestial kingdom). But this was not the case. Reflecting on his labors as a construction foreman on the temple, Wandle Mace provided the following symbolic representation for the stone pieces: “The architecture of the temple was purely original and unlike anything in existence, being a representation of the Church, the Bride, the Lambs wife—John the revelator says in Rev. 12 ch. 1st verse ‘And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars.’ This is portrayed in the beautiful cut stone of this grand temple.”[23] Thus the sun-moon-star design represents the glory of the latter-day church or kingdom, further symbolized by the sun rising through the clouds, with the trumpets heralding the restoration of the gospel and the glory of the latter-day Church of Jesus Christ (see figure 7).

Nauvoo Temple Ruins

On 9 October 1848, just two and a half years after the main body of Latter-day Saints left Nauvoo to settle in the West, arsonists set fire to the abandoned temple, destroying the temple’s interior structure, the attic story, and the bell and clock tower, leaving a blackened facade and three unsupported sixty-foot walls.[24] In March 1849, David T. LeBaron, who had been appointed caretaker of the temple, sold the burned-out structure for two thousand dollars to the Icarians, a French-based utopian socialist group led by Étienne Cabet. The Icarians planned to refurbish and restore the temple, but as if destined by fate, on 27 May 1850, a tornado struck the temple shell, collapsing the north wall and severely damaging the west and south walls. Only the front of the temple withstood the blast, but it was structurally unsafe. During the next few years, the Icarians used stone from the rubble and what remained of the temple’s walls to build a school, a dining hall, and a few smaller structures. However, in 1856, the group splintered, and Cabet and his followers left Nauvoo.[25]

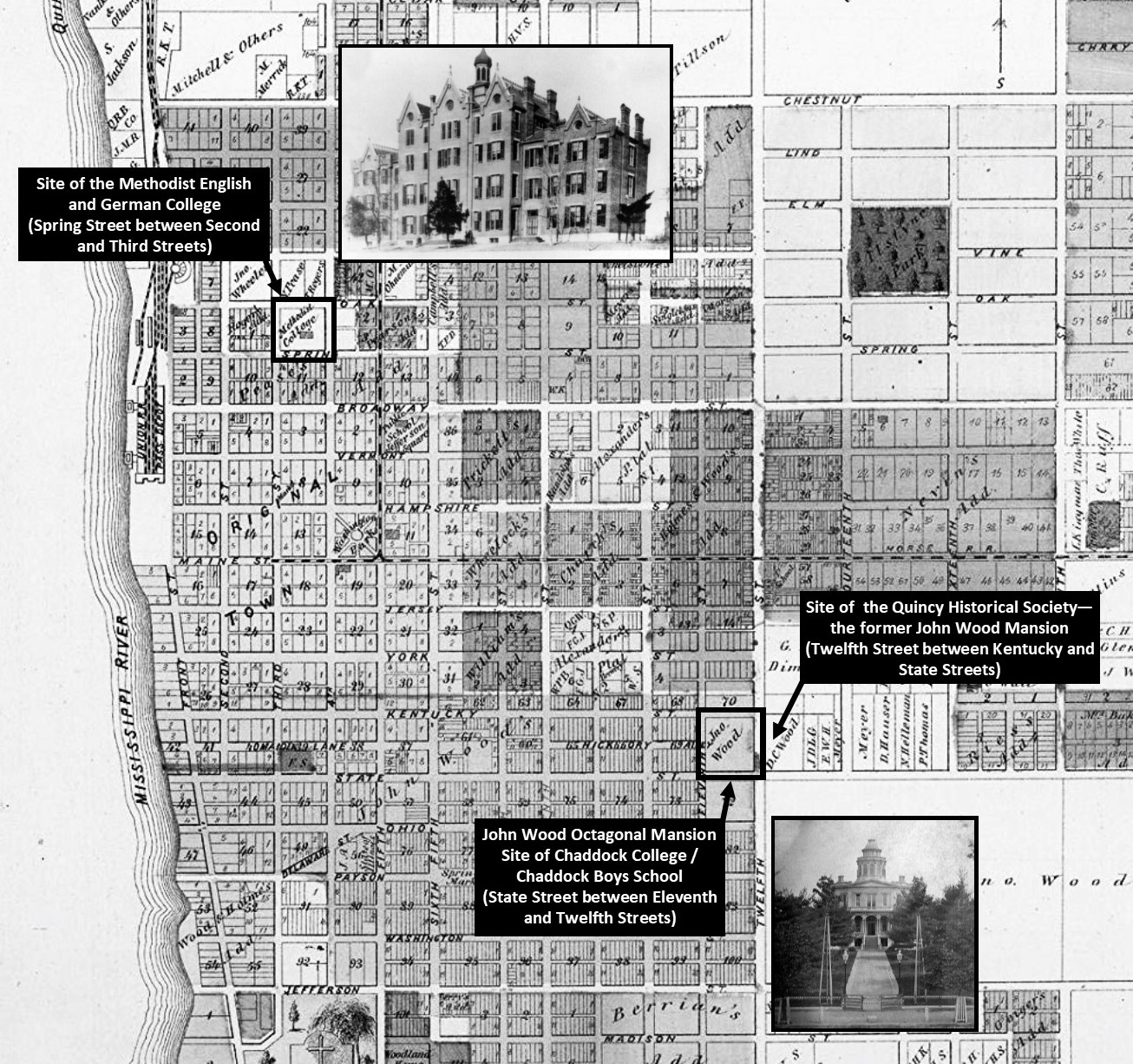

Figure 8. Map of Quincy, Illinois, showing the location of the Methodist English and German College/

Figure 8. Map of Quincy, Illinois, showing the location of the Methodist English and German College/

By 1865 only a portion of the southwest corner of the original temple remained. As a safety measure, an explosive was used to bring it down. A newspaper reporter wrote that following the demolition, some of the ornamental stonework (with probable reference to the sun, moon, and star stones) had been saved by the current owner of the property, a Mr. Dornseiff (first name not known), and were sold or given to “curiosity seekers in all parts of the country.”[26]

Two Original Sunstones Survived

At that time (1865) George W. Gray, president of the Methodist English and German College, in Quincy, Illinois (often referred to as the Methodist College), went to Nauvoo, where he acquired two sunstones from what remained of the Nauvoo Temple. The sunstones were intact, but the base stones and the top abacus stones were missing. Given the circumstances surrounding the temple’s destruction, first by fire, then by windstorm, and then by detonation, it is remarkable that the two sunstones remained unbroken and sustained only minor damage. Gray transported the capital stones by steamboat to Quincy, where they were placed on opposite sides of the main entrance of the school grounds of the college, which at the time was located at Third and Spring Streets (figures 8 and 9).[27] In time, these two stones would find different twentieth century homes; one would return to the Church, and the other would end up in the Smithsonian.

Figure 9. The Methodist English and German College, Quincy, Illinois, 1884. The building housed the college from 1847 to 1875, after which it was sold to the Quincy School Board and renamed the Jefferson School. At one time, two Nauvoo Temple capital sunstones were displayed on the school property. Quincy Area Historic Photograph Collection, Quincy Public Library, Quincy, IL.

Figure 9. The Methodist English and German College, Quincy, Illinois, 1884. The building housed the college from 1847 to 1875, after which it was sold to the Quincy School Board and renamed the Jefferson School. At one time, two Nauvoo Temple capital sunstones were displayed on the school property. Quincy Area Historic Photograph Collection, Quincy Public Library, Quincy, IL.

Nauvoo Latter-day Saint Visitors’ Center Sunstone—the “Sister Sunstone”

In 1870 one of the sunstones from the Methodist English and German College was donated to or acquired by the State of Illinois and taken to Springfield, where it was placed on the old statehouse grounds (the former state capitol building made famous by Abraham Lincoln). In 1876 the sunstone was moved southwest four blocks to the new state capitol grounds, where samples of native Illinois stones were being brought for the new capitol building (the current state capitol), which was then under construction. The stone remained there until 1894, when it was moved to the entrance of the Illinois State Fairgrounds in Springfield and placed in the middle of a decorative lily pond, where it remained until 1955. It was then moved again, this time to the Nauvoo State Park.[28] It remained there until 1992, when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was made custodian of the sunstone. In June 1994, it was relocated to the original temple block on the bluff and placed in a sealed display case to protect it from vandalism and the elements.[29] In 1999 the stone and the sealed display case were moved just outside the north entrance to the Nauvoo Latter-day Saint Visitors’ Center. Finally, in November 2012, the stone was placed in an open display case inside the visitors’ center (figure 10).[30]

Figure 10. Sunstone from the original Nauvoo Temple. Following the destruction of the temple, this sunstone was one of two sunstones procured by George W. Gray in 1865 and taken to Quincy, Illinois, where it was displayed on the grounds of the Methodist College. It was later moved to the state capital in Springfield, Illinois, and displayed on the capitol grounds of the old and current state capitol buildings and on the Illinois State Fairgrounds. In 1955 it was moved to the Nauvoo State Park. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints became the custodian of the stone in 1992. Photograph by author, 2013.

Figure 10. Sunstone from the original Nauvoo Temple. Following the destruction of the temple, this sunstone was one of two sunstones procured by George W. Gray in 1865 and taken to Quincy, Illinois, where it was displayed on the grounds of the Methodist College. It was later moved to the state capital in Springfield, Illinois, and displayed on the capitol grounds of the old and current state capitol buildings and on the Illinois State Fairgrounds. In 1955 it was moved to the Nauvoo State Park. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints became the custodian of the stone in 1992. Photograph by author, 2013.

The Quincy-Smithsonian Sunstone

The second sunstone remained on the property of the Methodist English and German College on Spring Street for several years. In 1872 the college merged with Johnson College. Three years later, in December 1875, the college officials sold the property and the building to the Quincy Board of Education for $30,000, and it became the Jefferson School (an elementary school). Following the sale, the college relocated in 1876 to the John Wood Octagonal Mansion located on State Street, between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets (figure 8). At the same time, Charles C. Chaddock gave the college $24,000, and the name of the school was changed to Chaddock College.[31] In 1890 the college became a private school for boys ages six to sixteen and was renamed Chaddock Boys School.[32]

Figure 11. The John Wood Octagonal Mansion, on the main campus building of Chaddock College/

Figure 11. The John Wood Octagonal Mansion, on the main campus building of Chaddock College/

How long the sunstone remained on the Jefferson School property is unknown, but D. L. Musselman Sr., an assistant administrator at the elementary school, remembered that the stone was in the schoolyard for years and that the children attending the school were known to crack nuts and sharpen their pencils on the nose of the stone’s face. Recognizing the historical significance of the stone, Musselman made arrangements with Chaddock College officials to have the stone moved from the Jefferson School property to the grounds of the college. It is not known exactly when the sunstone was moved to the Chaddock College/

Figure 12. Nauvoo sunstone on Chaddock College/

Figure 12. Nauvoo sunstone on Chaddock College/

Several photographs of the sunstone on the Chaddock College/

Figure 13. Nauvoo sunstone on the Chaddock College/

Figure 13. Nauvoo sunstone on the Chaddock College/

Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County Acquisition

In December 1912, officials and administrators of the Chaddock Boys School made arrangements to purchase a new location for the school at Twenty-fourth and Jersey Street in Quincy. (The current Chaddock School in Quincy still occupies this property.) Rather than move the sunstone to the school’s new location, the school trustees made inquiries to the Quincy Historical Society—housed in the former John Wood Mansion (not to be confused with the John Wood Octagonal Mansion) located across the street to the east of the Chaddock School property—to see if the society would be interested in acquiring the sunstone at no cost. Given the stone’s historical significance, and the fact that the school was not asking for any money, the society accepted the offer.[34] On 11 January 1913, the sunstone was moved to a location on the south side of the society’s building in a partially covered area. Sometime later it was moved to a spot on the northeast side of the main lot.[35]

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History Acquisition

For much of the twentieth century, the Nauvoo Temple sunstone remained on display on the property of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, where, unfortunately, it continued to be exposed to the elements. This exposure resulted in noticeable signs of deterioration over the years. Eventually, the society’s officials realized that the sunstone’s deteriorating condition would necessitate investing in costly conservation and restoration work if it were to be preserved. They further reasoned that the sunstone had little connection to Quincy and questioned whether or not to continue to retain ownership of the relic, given its lack of relevance to the area’s local history. After all, it was a Latter-day Saint artifact from Nauvoo, not Quincy. For these and other reasons, in the late 1970s, the society officers decided to try to find a buyer. Discussions with officials from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints took place on and off for ten years but without success. Finally, in early 1988, negotiations ended when the Church formally rejected the idea of purchasing the sunstone. When these talks ended, the directors of the society hired an agent who was given an asking price and charged to “seek a good home for the sunstone.” The directors also decided to reject the idea of selling the stone to a private collector, so that that sunstone would find “a place in a public repository where it would receive the largest ‘public exposure.’” The agent had discussions with officials from the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now the Community of Christ), but they also rejected the society’s offer. It was at this time that the agent approached administrators from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and the negotiations were successful. The museum sent two representatives to Quincy, one to confirm the authenticity of the stone, and the other to take photos and examine the stone’s condition. In October 1988, the Smithsonian’s directors agreed to the asking price—$100,000.[36] “It was one of the largest expenditures the museum ever made,” said Richard Ahlborn, curator in the museum’s division of community life. “That’s because we’re a history museum and artifacts usually don’t cost that much. . . . In fact, the board of regents of the Smithsonian had to approve it.”[37] On 9 December, Joel W. Scarborough, president of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, announced the sale by letter to the organization’s members:

The Society’s Board of Directors authorized the acquisition by the Smithsonian Institute for several reasons. The sunstone has primarily a Nauvoo historical connection. It has little meaningful historical association with Quincy. . . .

At its outdoor location . . . the soft limestone sculpture is subject to weathering and deterioration and vandalism. The location in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History will enable conservation experts to preserve and protect this interesting monument.

Over six million people visit the Smithsonian each year. Far more people will have a chance to view the sunstone in “America’s Museum” than would ever see it in Quincy. . . .

The sunstone will be welcomed and preserved in its new location in America’s most prestigious museum, sheltered from the ravages of time and elements of man and nature.[38]

Figure 14. Richard E. Ahlborn, Community Life curator for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, by the Nauvoo Temple sunstone exhibit. Ahlborn played a leading role in securing the sunstone for the museum. Photo by Rick Vargas. National Museum of American History, 1990.

Figure 14. Richard E. Ahlborn, Community Life curator for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, by the Nauvoo Temple sunstone exhibit. Ahlborn played a leading role in securing the sunstone for the museum. Photo by Rick Vargas. National Museum of American History, 1990.

Within a week after the announcement, a three-man crew, headed by Wayne Field, supervisor of the Smithsonian’s rigging shop, arrived in Quincy to transport the sunstone to the Museum of American History in Washington, DC.[39]

Before the stone could be displayed, the Smithsonian’s professional conservators first needed to perform an extensive cleaning. Most noticeable were patches of green algae and a black sulfate-like crust, both of which were chemically removed. The blue-colored paint on the sunstone’s pupils proved to be more difficult. Martin Burke, one of the museum’s conservators said that the stone was so porous that they were unable to remove all the paint from the eyes. “We tried an arsenal of solvents,” he said, but finally “settle[ed] for a little watercolor ‘make up’ to cover up the traces.”[40]

Museum staffers also had to design and create the exhibit to provide information to patrons. This included background information about Latter-day Saints and a history of the Nauvoo Temple, as well as architectural drawings and photographs. The final procedure involved the actual construction of the exhibit—no small task, considering that the designers had to figure out how to construct a platform for the two-and-a-half-ton stone. All of these processes took considerable time.

Figure 15. Location of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone exhibit in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History from 1990 to 2012. Photo by author, 1998.

Figure 15. Location of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone exhibit in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History from 1990 to 2012. Photo by author, 1998.

In early January 1990, a little over a year after the Smithsonian acquired the sunstone, the reconditioned artifact was displayed for the first time.[41] The exhibit was located in the main floor gallery, immediately to the west of the museum’s most prominent exhibition—the Star-Spangled Banner, the historic flag that flew over Fort McHenry during the British bombardment of Baltimore during the War of 1812. Curator Richard Ahlborn noted the significance of the sunstone’s location. “Except for the Star Spangled Banner,” he said, “you couldn’t ask for a more central location.”[42] The sunstone rested on an eight-foot pedestal so visitors would look up, similar to how they would have looked up to see it on the original temple (see figures 14 and 15). It remained in this location in the museum for twenty-two years.

In April 2012, a new exhibition opened in the National Museum of American History called “American Stories” and was located in the northeast section on the main floor of the museum. The exhibition included objects that examined or represented “the manner in which culture . . . [has] shaped life in the U.S. and how the peopling of America has contributed to the rich distinctiveness of a country influenced by diverse cultural communities.”[43] Recognizing the unique influence the Church has had on the religious culture and landscape of American history, the Smithsonian’s administrators and staffers relocated the Nauvoo Temple sunstone to the new exhibit, where it currently remains (see figures 16–19).

Figure 16. “American Stories” exhibition, Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The Nauvoo Temple sunstone is a major feature of the exhibit. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 16. “American Stories” exhibition, Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The Nauvoo Temple sunstone is a major feature of the exhibit. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 17. Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “Expansion and Reform” section of the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 17. Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “Expansion and Reform” section of the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 18. Side view of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 18. Side view of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 19. Front view of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Figure 19. Front view of the Nauvoo Temple sunstone in the “American Stories” exhibition in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by author, 2018.

Conclusion

What makes the Nauvoo sunstone such an important and significant artifact that it has found a place in the Smithsonian’s collection? Curator Richard Ahlborn noted, “Few religions have their beginnings in America. That alone is quite a phenomenon, not to mention the strength and growth the Mormon Church has shown. The stone is symbolic of the most persistent religious movement in American history.”[44] Journalist and author Elizabeth Schleichert observed that the sunstone symbolized “the tumult and tragedy of the early Mormons.”[45] True indeed! The sunstone symbolizes the early beginnings of the Church, the determination of its leaders and members to prevail against their antagonists, and the tragedies and setbacks that accompanied the Church during the first two decades of its existence. But the Nauvoo sunstone is representative of something more—much more. Ultimately, this rare artifact represents the commitment and sacrifice of a people to build a temple wherein they could worship God, make covenants, and receive the ordinances that they believed were necessary to bring about their salvation and ultimate exaltation in the kingdom of God. A fitting epitaph to that purpose was inscribed above the pulpits on the east wall of the abandoned temple’s main hall by someone before leaving Nauvoo for the journey to the west: “The Lord has beheld our sacrifice: come after us.”[46]

Notes

[1] Richard Kurin, The Smithsonian’s History of America in 100 Objects (New York: Penguin Press, 2013), 153, 156.

[2] See Joseph Smith, “Epistle to the Saints,” JS History, vol. C-1, 1092–93, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, hereafter cited as CHL.

[3] See J. Earl Arrington, “William Weeks, Architect of the Nauvoo Temple,” BYU Studies 19, no. 3 (Spring 1979): 340.

[4] Revelation, 19 January 1841, in Matthew C. Godfrey, Spencer W. McBride, Alex D. Smith, and Christopher James Blythe, eds., Documents Volume 7: September 1839–January 1841, vol. 7 of the Document series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 518; see Doctrine and Covenants 124:42.

[5] JS History, vol. E–1, 1875–1876, CHL.

[6] William Weeks, Nauvoo Temple architectural drawings, drawing 5, MS 11500, William Weeks Papers, CHL. While the sunburst motif appears in various forms in architectural patterns and ornamentations, the inclusion of a face in the sun generally does not. However, an exception to this is the sunburst engraving on the top of the chair that George Washington occupied during the Constitutional Convention held in Independence Hall in Philadelphia in 1787, known as the speaker’s chair. One of the chair’s most noticeable features is the sunburst on the top of the chair that shows a partial human-like face in the sun. Weeks may have been familiar with the famous chair and adapted the sunburst design for his initial design for the sunstone, but the more likely conclusion is that Weeks took the often-used architectural sunburst motif and adapted it to suit Joseph Smith’s visionary understanding.

[7] Weeks, Nauvoo Temple architectural drawings, drawing 2, CHL.

[8] Brigham Young, “The Placing of the Last Capital on the Temple,” in Joseph Smith Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed., rev., 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1971), 7:323. It is important to note that although Young indicated each capital included “five stones,” it was actually only four. Situated above the top of the sunstone was an abacus stone or what Young called “the cap.” But above the abacus stone was another abacus layer of stone that went all the way around the temple, which explains why Young indicated the capitals consisted of five stones. The additional abacus layer can be seen in several of the photographic images of the original Nauvoo Temple.

[9] George D. Smith, ed., An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991), 533.

[10] It is not known who crafted the moonstones. The moonstones are not nearly as ornate as the sunstones and would require less skill by the stone carver to fashion. Two moonstones are known to exist. One is on display in the Joseph Smith Historic Site, owned by the Community of Christ (formerly RLDS). Blake M. Roney, cofounder and former chair of Nu Skin, procured an original moonstone and later donated it to the LDS Church in the late 1990s. According to Roney, the moonstone is being stored in Nauvoo, Illinois.

[11] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson, eds., Journals Volume 2: December 1841–April 1843, vol. 2 of the Journal series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jesse, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 329.

[12] David Nye White, “The Prairies, Nauvoo, Joe Smith, the Temple, the Mormons, etc.,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 15 September1843, 3.

[13] Charles Lambert, Autobiography, circa 1885, 13, typescript, MS 1130, CHL.

[14] William Clayton, History of the Nauvoo Temple, 96, MS 3365, CHL. Clayton’s history is also cited in the Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 31 December 1843, 96, CHL; see also Benjamin Mitchell, Autobiography, in Autobiographies of Early Seventies, typescript, 53, CHL.

[15] See Nauvoo Temple Committee Daybook E, 6 December 1844, 58, CR 342 9, CHL.

[16] James Henry Rollins, Reminiscences, 23–24, typescript, MS 2393, CHL.

[17] Josiah Quincy, Figures from the Past from the Leaves of Old Journals (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1883), 389–90. See also Jed W. Woodworth, “Josiah Quincy’s 1844 Visit to Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 39, no. 4 (2000): 71–87.

[18] Roger P. Jackson to Alexander L. Baugh, 24 October 2019, in author’s possession. Jackson is president of FFKR Architects in Salt Lake City and the architect of the reconstructed Nauvoo Illinois Temple, completed in 2002.

[19] See Clayton, History of the Nauvoo Temple, 59–60; see also Smith, History of the Church, 7:274, 323–24.

[20] Clayton, History of the Nauvoo Temple, 60; see also Smith, History of the Church, 7:323–24.

[21] Brigham Young, “An Epistle of the Twelve,” Times and Seasons 5, no. 18 (1 October 1844): 668.

[22] Clayton, History of the Nauvoo Temple, 62–63. Clayton also noted that the last capital was carved by Harvey Stanley.

[23] Wandle Mace, Autobiography, manuscript, 120, MSS 921, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, copy in author’s possession.

[24] Joseph Earl Arrington, “Destruction of the Mormon Temple at Nauvoo,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 40, no. 4 (December 1947): 418–19.

[25] See Matthew S. McBride, A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 360–63; and Glen M. Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 627–30.

[26] Carthage Republican, 2 February 1865, as cited in Virginia S. Harrington and J. C. Harrington, Rediscovery of the Nauvoo Temple: Report on Archaeological Excavations (Salt Lake City: Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., 1971), 6.

[27] D. L. Musselman Sr., to Mr. E. G. Thompson, 9 November 1903, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Quincy, Illinois (hereafter cited as HSQAC), copy in author’s possession. See also Joel W. Scarborough to Dear Historical Society Member, 9 December 1988, HSQAC, copy in author’s possession.

[28] “Nauvoo Sunstone a Century Later,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 50, no. 1 (Spring 1957): 100; see also Carl Landrum, “Sun stones go back to Mormons,” Quincy Herald-Whig, 7 August 1983, 4E.

[29] See “Sunstone is unveiled at the temple site,” Church News, 2 July 1994, 7; also Nauvoo Temple Sunstone Commemoration Program, 26 June 1994, M282.1 N314scp 1994, CHL.

[30] Benjamin C. Pykles to Alexander L. Baugh, November 26, 2019, copy in author’s possession. Pykles is the historic sites curator for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[31] See Carl and Shirley Landrum, Images of America: Quincy, Illinois (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1999); and Carl and Shirley Landrum, Landrum’s Quincy, vol. 4 (Quincy: Justice Publications, 1997), 146.

[32] See “Chaddock College,” Wikipedia.

[33] D. L. Musselman Jr., to the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois, 14 October 1953, MS 361, HSQAC, copy in author’s possession. Musselman also said that before the sunstone was moved from the Jefferson School ground to the Chaddock College campus, it was placed for a short time on the grounds of Washington Park in downtown Quincy, but there is no existing documentation to support this. A short newspaper article published in the Quincy Herald-Whig states that after the stone was moved from the Jefferson School property to the Chaddock College campus, the local school board challenged the acquisition of the Mormon relic by the college. See “From the Mormon Temple,” undated Quincy Herald-Whig newspaper clipping, MS 361, HSQAC.

[34] J. H. Grafton to J. W. Emery, 4 December 1912; J. W. Emery to J. H. Grafton, 5 December 1912 (the letter was incorrectly dated 1913); J. H. Grafton to J. W. Emery, 12 December 1912; and J. H. Crafton to J. W. Emery, 12 December 1912, HSQAC, copies in author’s possession. J. H. Grafton represented the trustees of the Chaddock Boys School, and J. W. Emery was the president of the Quincy Historical Society.

[35] Joel W. Scarborough to Dear Historical Society Member, 9 December 1988.

[36] See Eric Johnson, “Historical Society sells Mormon Temple ‘sunstone’ to Smithsonian Institution,” Quincy Herald-Whig, undated newspaper clipping, HSQAC, circa 9 December 1988, copy in author’s possession.

[37] Richard E. Ahlborn, as quoted in Lee Davidson, “Smithsonian pays $100,000 for sunstone from Nauvoo Temple,” Church News, 2 December 1989, 5.

[38] Joel W. Scarborough to Dear Historical Society Member, 9 December 1988. See also Eric Johnson, “Smithsonian pays $100,000 for Mormon Temple sunstone,” Quincy Herald-Whig, 13 December 1988, 10–B, HSQAC, copy in author’s possession.

[39] Johnson, “Smithsonian pays $100,000,” 10–B; and “Crew begins removing sunstone,” Quincy Herald-Whig, 15 December 1988, newspaper clipping, HSQAC, copy in author’s possession.

[40] “Around and About SI,” The Torch, July 1990, 2. The periodical is the Smithsonian employee newsletter.

[41] See Joel W. Scarborough to Dear Historical Society Member, January 1990, HSQAC, copy in author’s possession.

[42] Richard E. Ahlborn, as cited in Davidson, “Smithsonian Pays $100,000,” 5.

[43] See “‘American Stories’ Exhibition Opens at National Museum of American History,” https://

[44] Richard E. Ahlborn, as cited in Davidson, “Smithsonian pays $100,000,” 5.

[45] Elizabeth Schleichert, “The object at hand,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 1994, 14.

[46] Charles Lanman, Summer in the Wilderness; Embracing a Canoe Voyage up the Mississippi and around Lake Superior (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1847), 32. In July 1847, while on his river excursion, Lanman stopped at Nauvoo, where he spent several hours in the community during which time he was given a personal tour of the Nauvoo Temple by an unnamed Latter-day Saint, possibly Joseph L. Heywood, John S. Fullmer, or Almon W. Babbitt, who had been appointed trustees of the Church’s properties and had remained in Nauvoo. Lanman’s narrative about Nauvoo comprises four printed pages.