Uruguay: Organizing the Members

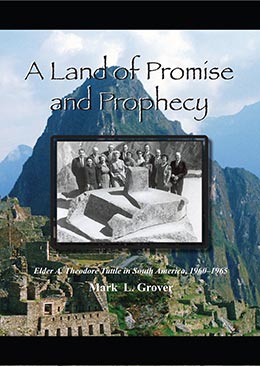

Mark L. Grover, "Uruguay: Organizing the Members," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 153–85.

As head of general sales for the A. B. Dick Company, Jeep Jordan did not understand these Latter-day Saints. He had found the man he wanted with him at company headquarters in Chicago, and he was willing to pay him well. After two weeks of negotiations the answer was no; this man did not want to leave Utah, his roots, and his family. ZCMI, the Church-owned department store, was where he wanted to stay. Now a year later, after one brief phone call, this same man was uprooting his immediate family, not to Illinois but thousands of miles away to Uruguay—at a position with no salary, just living expenses! Jordan expressed his frustration for the entire company, “We don’t understand.”[1]

It is an act that most outside of the Church do not comprehend nor appreciate. Faithful members are so dedicated to the Lord that they are willing to leave homes, good jobs, and prestige to work as missionaries. Many people are unaware of the covenants Church members enter into with the Lord. Others may lack understanding of the powerful influence of the Spirit in confirming those decisions. It was the covenants they made and their spiritual confirmations that persuaded Thomas and Helen Fyans to leave Utah and go to Uruguay.

In May 1960, the Fyanses were on their way to a convention of the A. B. Dick Company in Chicago, where Tom was to give a presentation on marketing. He turned the business trip into part vacation, part work, and Helen came with him. They went by train from Salt Lake City to Chicago so they would have time “in which to slow our lives down and meditate.” As they got close to Chicago, they both had experiences they did not completely understand: “The most unusual feeling that something unusual was going to happen came over us. . . . Strong emotions welled up within us. We both had tears in our eyes as we felt this strange spell that neither of us could explain.” The Fyanses did not know what was going to happen, so they wrote letters of appreciation to some of their closest friends.

Fyans family.

Fyans family.

As soon as they got to their hotel in Chicago, the phone rang and the hotel receptionist told them that a Mr. Moyle from Salt Lake City would call them in two hours. It was a long two hours of waiting and wondering. When the call came, President Henry D. Moyle said how difficult it had been to find them: “I’ve traced you clear across the United States, and I’m glad I finally found you.” After conversing about how they were doing, he said he had been asked by President McKay to call them to preside over the Uruguayan Mission. The Fyanses expressed their surprise and appreciation for the call and accepted the assignment. As soon as they hung up, they hunted on a map where exactly Uruguay was.

Tom called his supervisor at ZCMI, who suggested they return home immediately. Then he called Jeep Jordan to say he would not be able to make his presentation because he was returning to Salt Lake City immediately and would be going to South America in a few weeks. That is when Jordan wondered about the Fyanses’ religion. With a simple phone call, the Fyanses accepted the assignment immediately and readied themselves to leave home within a few weeks. Jordan may not have understood how or why such devotion existed, but he respected their decision. In fact, he offered Tom a position with his company when he returned from South America.

A Brief History

The fact that the Fyanses had to locate Uruguay on a map was not surprising. Uruguay does not have much fame or recognition in Latin America, let alone the world. Historically, it has always been a country in between. To its north is the rich and powerful Brazil; to the south, the equally rich and powerful Argentina. Uruguay, on the other hand, is not rich, large, or powerful. This country of 68,000 square miles (the size of the state of Kansas) has gently rolling hills that at the time of the Spanish discovery were wooded valleys and grass-covered slopes. W. H. Hudson called it the “purple land” because of a purple tinge on its tall prairie grasses.[2]

Uruguay never attracted any of the European colonial powers because it lacked the gold and rich, tropical land of its neighbor to the north and the humid pampas of Argentina to the south. In fact, for two hundred years after the land was discovered by Spanish explorers, no fixed settlements were established in the region. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, cattle were allowed to run free throughout the country. They multiplied freely, and soon large herds developed. The cattle attracted the famous cowboys of the region, the gauchos, who came to round up the animals not for the meat but for the hides, which were shipped to Europe. After a time, European buyers established outposts throughout the country and hired gauchos to collect the hides. These outposts or ranches developed into small settlements that were the foundation for the present towns and cities scattered throughout the country.[3]

The geographic position of Uruguay between the Spanish and Portuguese empires became the major reason for the development of settlements. In 1680 the Portuguese government moved troops into the area and built a fort on the Río de la Plata opposite Buenos Aires called Colonia del Sacramento. The Spanish were not too concerned because their most important settlements were further up the river connected to the gold fields of Peru, not Buenos Aires. It was not until 1726 that the Spaniards became concerned enough to establish the city of Montevideo closer to the Atlantic Ocean in direct response to Portuguese activities in the area. Independence from Spain came to Uruguay as a result of its relationship with the local leaders in Buenos Aires. Brazil included Uruguay as part of its national territory when they broke from Portugal in 1822. However, a combined Uruguayan and Argentine army defeated the Brazilians in 1825 and expelled them from Montevideo in 1828. The British, who had significant political influence in the region, persuaded both Brazil and Argentina in 1928 to recognize Uruguay as an independent country. Uruguay’s primary international function was to act as a buffer state between the two powers. It has served well in the role, probably eliminating numerous conflicts that would have occurred between the two neighboring powers.[4]

For the first half of the twentieth century, Uruguay was considered the most stable and democratic country in Latin America. This was largely due to the influence of Uruguay’s political leader, José Batlle y Ordóñez. After serving as president from 1903 to 1907, he studied democracy throughout the world and during his second term, 1911–15, introduced important reforms into the political system through a new constitution in 1919. Ordóñez was impressed with the neutral and democratic role of Switzerland and believed Uruguay could follow in its footsteps. Though there continued to be political struggles, most of his reforms were accepted by the country’s politicians, which resulted in power sharing between the two major political parties. The product of the reforms was a democratic system unlike any found in the rest of Latin America. The Uruguayans were pleased with their political reforms, including freedom of the press and the free flow of ideas without fear of repression. Most important to missionary work was a section in their constitution declaring complete freedom of religion, something for which the Uruguayans were proud. An accompanying disdain for the political role of the Catholic Church made the entrance of other churches acceptable because many saw religious competition as a healthy attribute of their culture.[5]

The Church in Uruguay

Uruguay may have been ignored by the world, but not by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Uruguay was the third country in South America to have missionaries, and the Church has developed an influence there unequaled in most nations. Much of that early influence had to do with the personality and role of Frederick S. Williams. Williams was one of the great pioneers of the Church in Latin America whose influence in Uruguay continues today.

In 1926 eighteen-year-old Williams listened intently during a ward sacrament meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, as Elder Melvin J. Ballard, recently returned from South America, described his mission to Buenos Aires. At this meeting Williams decided first that he wanted to go on a mission and second that he wanted to go to Argentina. After the meeting he talked with Elder Ballard and made his desires known. His call to Argentina came within a couple of months, and he left for Argentina in February 1927. He and his companion became the seventh and eighth young missionaries in the country. After his mission and subsequent marriage to Corraine Smith, he worked in a variety of jobs until 1938, when he received a call to return to Argentina as mission president. When he returned to the United States in 1942, he found work as a business manager in the Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the U.S. State Department. In this position he returned to Latin America, first to Venezuela and then Uruguay. In Uruguay there were several American members of the Church working for the U.S. government, and in June 25, 1944, a branch of the Church was organized with Frederick Williams as the branch president. Meetings were held in his home in English. He left Uruguay in early 1946 not realizing he would be returning in little over a year and a half.[6]

After returning home to Salt Lake City, he visited with several friends and former missionaries to Latin America about the apparent lack of interest in Latin America by Church leaders. One of those friends, Don Hyrum Smith, was President George Albert Smith’s nephew. Don Smith was able to schedule a meeting with the prophet, and Williams was chosen as spokesman for the group. In the meeting, after expressing reservations about making suggestions to the prophet, Williams described the concerns the group had. He summarized the history of the Church in South America and indicated that no General Authority had visited the area on Church business since Elder Ballard left in 1926, twenty years earlier. He told about his experiences in Venezuela and Uruguay and talked freely about the history and social makeup of the countries. He suggested that certain countries appeared to be ready to receive the gospel, based primarily on social development and the level of religious freedom. A quiet President Smith asked for permission to leave and within a few minutes returned with his second counselor, President David O. McKay. Williams summarized what he had said and waited for a reply. Both leaders indicated their appreciation and asked Williams to put into writing his ideas, including suggestions as to where the Church could introduce missionaries.

In a twenty-page summary, seven countries were suggested ready for missionaries, with Uruguay leading the list. Eight months later, in April 1947, from President McKay made a phone call to Williams and asked, “Do you remember recommending opening a mission in Uruguay? How would you like to go down and open it?” He and Corriane were delighted, and President McKay asked that they get to Uruguay as soon as possible. Several missionaries called to the Argentine Mission, were at that time in Uruguay, unable to get to their final destination due to the Argentine government’s refusal to grant visas. President McKay hoped these eighteen missionaries would be the foundation for a new mission in Uruguay. On August 30 the Williams family arrived in Montevideo aboard a small ship, the General Artigas, that crossed the Río de la Plata from Buenos Aires. The ship had a fitting and symbolic name because Artigas was the father and founder of independence for Uruguay, much as Williams would become for the Church there. They were able to get through customs in fifteen minutes with many bags and boxes, an unusual occurrence. That was to be a trademark of the mission under President Williams. His experience working for the U.S. government had resulted in them having many friends in high places and receiving privileges not normally experienced. He used those connections first to get through customs and then to establish the Church. His connections with a prominent lawyer and senator resulted in getting the necessary papers granting him power of attorney for the Church in Uruguay and for renting the first mission home. His many friendships helped establish the Church throughout the country. But more important, the respect government officials held for President Williams led to the perception of a Church not of poor immigrants as in Argentina and Brazil, but one of respect and prestige. A healthy mistrust of the Catholic Church in Uruguay also helped establish the LDS Church there.

President McKay suggested the missionaries would be transferred from Argentina and would be waiting for the Williamses in Uruguay. President Williams had a month and a half to get ready before the first missionaries arrived. Three missionaries were transferred from Argentina, and on October 24 three missionaries arrived from the United States. By December 10 they had twenty-four missionaries, three of whom spoke adequate Spanish, because missionaries at that time were going to the field without language training. The General Authorities felt it was important that the mission get a good start and sent missionaries on a regular basis. It soon became comical. Missionaries would arrive, receive a couple of weeks of language training, be made a senior companion, and be given a newly arrived missionary who also spoke no Spanish. They would then be sent into the field to open new cities with what President Williams described as “their halting but sincere Spanish.”[7] Investigators did not like the speed with which missionaries were moved into an area and then transferred, but President Williams had no option. He had to find a place to put the missionaries.

Within months there were more missionaries in Uruguay than in Brazil, and within a year more than in Argentina. The number of missionaries called to Uruguay was equal to or higher than the rest of South America until second missions were organized in Brazil in 1959 and Argentina in 1962.[8] But the total population size in the three countries were vastly different. In Uruguay in 1960, the population was just more than 2.5 million, as compared to Argentina with twenty million and Brazil with eighty million.[9]

A comparison of the number of missionaries per citizens in the country is revealing. In Uruguay in 1960 there was one missionary called for every 16,761 Uruguayans. That ratio of missionary to total population was much higher than even in the United States. To have an equivalent ratio of missionaries to population, Argentina would have had 1,230 missionaries (they had 152); Brazil, 4,277 (273); and the United States, 10,779 (3,751) missionaries.[10]

Equally important was the way the population was scattered throughout the country. Uruguay is a country in which the capital city dominates everything. More than half the population lived in Montevideo. The rest of the population was scattered throughout the country in small towns, none of whom in the 1950s had more than fifty thousand people. Consequently, as the Church expanded outside of Montevideo into the interior, missionaries were going into towns much smaller than in Argentina or Brazil. Outside Utah, the Church presence in terms of missionaries was greater in Uruguay than almost anywhere else in the world.

When missionaries went into any Uruguayan town, their presence was obvious. The smaller towns often had four or six American missionaries. The local residents may not have known what they were doing, but they knew they were there. Strange stories would circulate about these young men in white shirts, ties, and hats, and sisters in dresses. In the 1950s, when there was a great fear of communism, many surmised these Americans were communists. By the sixties, when the political leftists were active in Uruguay, the missionaries apparently changed sides and were working with the American CIA. Why four to six agents of the CIA would be interested in the small towns of Uruguay might seem odd, but that was often the belief of the general populace. Uruguayans who made contact with the missionaries and joined the Church did so with great testimony and faith because they also faced the misperceptions directed toward the missionaries.[11]

The presence of many missionaries resulted in baptisms. When the Williams family arrived, the only members in the country were a few Americans and a French family by the name of Argault consisting of the mother, Jeanne Seguín, and daughter Eduarda. (A second daughter had moved to Canada.) This family had immigrated from France to Argentina, where they joined the Church and then moved to Uruguay. Though the early meetings were attended by a large number of investigators, the first baptism in Uruguay took time to happen when three members were baptized on November 4, 1948, almost a year after the mission had opened. After these three joined the Church, the numbers baptized significantly increased. It was not long until the Uruguayan Mission was baptizing more than either of the two missions in Brazil and Argentina.[12]

The expansion of missionary work into all parts of the country was rapid. Missionaries were going to all of the major cities of the country within a few months of the opening of the mission. In one case, the missionaries baptized a family in the small village of Isla Patrulla with a population of only a few hundred people. This family requested that missionaries permanently come to the area. President Williams decided to respond positively to their request because of their faith and to counteract Catholic propaganda that the Church was interested in only the people of the big cities. Elders Loyal Cecil Millet and Elwin T. Christiansen were assigned to open the city to missionary work. They established the Church in a home that had a sod roof and dirt floor. (The home was considered large for the region), and the floor was soon cemented, becoming the first home with a cement floor in the area. Wearing the traditional clothing of the local gauchos, the missionaries worked with the residents. Interest in the Church was significant, and meetings with close to one hundred people in attendance were common. The attendance was high because little else was happening in the village. The faith of the people of this small village so impressed Church leaders in Salt Lake City that they gave permission to build a small, beautiful chapel in the village, one of the first in Uruguay. Isla Patrulla was visited by several General Authorities. Over the years, the death of members as well as the lack of jobs in the area took a toll on the membership, and by 2001 there were only four members living in the village, with Church meetings held irregularly. The chapel continues to be the most important landmark in the village and is kept immaculately clean by a member of the Church.[13]

An important characteristic of the Church in Uruguay was the calling of local members, especially females, as full-time missionaries. That practice began when President Williams called the young French member, Eduarda Argault, on a mission in January 1948. This Uruguayan sister was assisted by sisters from Argentina, Elsa Vogler and Juana Gianfelice, and together they helped expand the Church. A significant percentage of the missionary force in Uruguay at that time consisted of local young men and women who contributed much to the growth of the Church. This tradition continues today, and many Uruguayan youth serve as missionaries.[14]

Another important aspect of the missionary experience in Uruguay was the participation of missionaries in public relations activities. Believing that the Church should build its reputation through positive activities not directly related to proselyting, President Williams decided to use the talents of missionaries and mention the name of the Church. These activities began first with the Williams family because Sister Williams was an accomplished musician. Sister Williams, along with her two daughters, presented musical programs throughout the country. President Williams then organized a missionary choir with the same purpose. The group eventually expanded to more than forty members, including Church members and investigators, and they traveled throughout the country. In the later concerts, the choir sang the mission song entitled “La Uruguaya,” a song President Williams wrote that expressed great appreciation and love for the country.[15]

The Church expanded into Paraguay during his presidency. One of his former Argentine missionaries, Samuel J. Skousen, was stationed in Paraguay as part of the U.S. Air Force. His missionary activity resulted in the first baptism when Skousen’s Paraguayan friend, Carlos Alberto Figueira, and his Brazilian wife, Malfada, became interested in the Church. Figueira was baptized August 21, 1948, in Asunción. His wife followed in January the next year. A branch of the Church was organized in Paraguay in July 1948 as part of the Uruguayan Mission. President Williams requested permission of the First Presidency to send missionaries into the country, which was granted at the beginning of 1950. Though a separate mission was not established until twenty-seven years later, missionaries have been in Paraguay since this time, making Paraguay the fourth nation in South America to have missionaries.[16]

President and Sister Williams were replaced in 1951 by Lyman and Afton Shreeve, who served until 1955. This period in Uruguay was characterized by membership growth and the development of young Church leaders, as a result of their serving missions. The most significant event in the Church during this period was the visit of President McKay in January 1954. President McKay presided over the placing of the cornerstone for the Deseret Chapel, the first Church building to be built in Uruguay. That chapel was dedicated eleven months later by Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. The Shreeves were replaced by President Frank D. Parry, and the growth and development of the Church followed in a similar pattern. Unfortunately, his presidency was interrupted by the death of his wife, who passed away during the visit of President Henry D. Moyle.

President Arthur M. Jensen replaced President Parry in 1957. This period had continued growth as the numbers of baptisms improved through new proselyting and teaching methods. Furthermore, organizational changes increased the amount of time missionaries spent proselyting, particularly in Montevideo. Jensen was interested in increasing the role of the members in the Church and called many of the local male members into positions of leadership. When Jensen arrived in Uruguay, almost all the branches were led by missionaries. His personal attention to training members as leaders was appreciated, and he is remembered for the care and interest he gave. Jensen’s efforts led to many Montevideo branches being presided over with local members and a district being organized. His final activity in December 1960 was to take President Joseph Fielding Smith, Jessie Evans Smith, and Elder Tuttle on a tour of the Uruguayan Mission. This was an important event for missionaries and members, which showed the maturation of the Uruguayan Mission in twelve short years.[17] When President and Sister Fyans stepped off the boat in Montevideo on December 2, 1960, they were surprised to be met by President and Sister Jensen, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve, and a member of the First Council of Seventy.

The growth of the Church in Uruguay during the next five years is one of the great stories of the development of the Church. The Church was well respected by the political and economic elites of the country. It had the highest baptismal growth rate in South America and had expanded into all regions and cities of the country. The members had begun to mature and were ready for the next steps that would put the Church on the same level as anywhere else in the world. The Lord had now chosen a businessman and organizer as the new president of the Uruguayan Mission. President Fyans was ready for what lay ahead.

Approach

President Fyans had a good idea what he wanted to do. He had been given his marching orders before arriving in Uruguay. At the Fyanses’ farewell held in the Butler Second Ward on November 13, 1960, President Moyle charged him to “lay a foundation for the organization of a stake in Montevideo.” Therefore, in the mission tour with President Jensen and the two General Authorities, he actively observed the mission and thought about how he would fulfill President Moyle’s mandate. Fyans immediately saw what his first challenge would be. The American missionaries were so involved in activities of administration for the branches and districts that they had limited time to do missionary work. He felt he had to get the missionaries out of branch and district responsibilities so they would have more time to teach. For this to happen, the members had to be put into positions of responsibility, where they would learn how the Church functioned.

Fyans was an administrator by profession. He had worked his way up through the managerial ranks at ZCMI and was in a position of significant responsibility when he left for his mission. He was successful because the departments he managed always reached their established goals. He was also a person of ideas. He loved to sit and develop plans of action. He enjoyed the process of creation. David Hoopes, one of the missionaries working as Elder Tuttle’s assistant, provided a description of how President Fyans worked: “I remember that President Fyans spent considerable time lying on his couch thinking about the direction the mission should go and programs that needed to be developed.” After time on the couch, he was soon at his desk with several notepads developing his ideas. One of his missionaries, Quinn Gardner, described the process: “I can see him sitting with a yellow pad on his lap. I can see him stretched out. I can see him with a soft grin on his face. But I can also see him hunched over his desk with several tablets folded back, several of them on different topics.”[18] After three months in Uruguay, President Fyans had his plan of action, the “Six Steps to Stakehood.” Elder Gardner described what it included: “The Six Steps was the strategic plan that if you would organize and develop organically the organization and its skills to perform the function of the Church, then you would end up having a stake.”[19]

President Fyans’s first concern for organizing a stake was the simple problem of numbers. They needed a specific number of active members for a stake to be organized. Thus the second component of his program was a plan to increase the numbers of those entering the Church. Elder Gardner described the program for increasing these numbers, named Channel 5: “Channel 5 was a way to marshal those people around certain core themes to capture their imagination in missionary work. Channel 5 was largely about converting members into being finders for the missionaries. Channel 5 was all about the missionary efforts that would fuel the people into the organization of a stake.”[20]

The two programs worked in harmony together. Channel 5 mobilized the members to find investigators for the missionaries to convert enough people for a stake organization. The “Six Steps to Stakehood” was a chronological plan of action that would train the leadership for organizing a functioning stake.

Member Organizations

President Fyans set a goal for growth to his missionaries: “Double the mission population by the end of the year.” His missionaries were somewhat shocked by the boldness of his plans.[21] To meet this goal, the missionaries had to be out proselyting and not involved with branch and district administration. President Fyans’s first task was to replace the missionaries with Church members in all activities not directly related to proselyting. During his first visit throughout the mission, his impression was not positive, and he wrote, “I got the feeling that this is a Salt Lake church. Missionaries in charge of everything.” So he made a decision that it had to change immediately. In the city of Montevideo many of the units were already under local leadership. It was in the smaller branches outside the city and in the interior that he focused his efforts. In the middle of one of his leadership meetings, he turned to his first counselor, Dwayne B. Williams, and gave him a combination threat and assignment: “Do you want an honorable release? Replace everyone of these branch presidents.” To have a Uruguayan in the leadership of every branch within three months became the mission goal: “You elders get prepared. Every week we’re going to be in a conference in some branch here and we’re going to appoint Uruguayan leadership.”[22]

Under the direction of Elder Williams, a step-by-step plan was devised to accomplish the task. The leadership of the mission looked at the individual branches “and came to the conclusion that we have men in the branches who can handle these positions. Not only do they have the abilities, but they should have the chance to develop them.” In the interior of Uruguay, only the two branches, Florida and Durazno, had complete member branch presidencies, and the branch in Minas had only a local branch president. In most of the other places, the missionaries had someone in mind who could serve as a branch president. A specific schedule was established for conferences. They interviewed members on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Then on Sunday at branch conference, a branch presidency with a local member as president was presented to the congregation for a sustaining vote. On January 15, 1961, a local counselor was called for Minas, and on January 29 the Trinidad Branch was put under complete local leadership: “To hear these brethren bear their testimonies and see their desire to serve the Lord strengthens our testimony. After seeing these men take hold there is no doubt in our minds that these men can do the job.” In February the Salto Branch was completely reorganized, and so it went for the next three months.[23]

The transition may appear to have happened smoothly, but it was anything but smooth. For example, on February 26 in the western city of Paysandú they came to the conference with no idea who would be the local branch president. When they arrived, they saw a man near the door by the name of José Maria Ghiorsi. President Fyans was informed he had been a member only five weeks and could not logically be called into the branch presidency. During their meetings President Fyans and the missionaries discussed the capacities of all the local members without coming up with the name of the branch president. A prayer was held and the Spirit felt, but the name of the new branch president was not made known.

The priesthood meeting of branch conference was held first, where testimonies were borne, including that of José. His desire was to “be a good Mormon. We were all touched very deeply with the man’s testimony.” They then went into sacrament meeting and were getting ready to sustain the officers, and the missionaries were not sure what to do. Fyans said to go ahead with the meeting. During the announcements and song, he was deep in thought. As they were about to sustain the branch president, who was one of the missionaries, Fyans asked them to postpone that part of the meeting. He got up and left the meeting, taking José Ghiorsi and his wife with him. President Fyans asked him to accept the position of branch president, which he did, with a healthy concern for what it meant. Fyans returned to the meeting and finished the sustaining. José, with only five weeks in the Church, was to be the branch president, and a second counselor was also called who had been a member only two weeks longer. Elder Williams stated, “The Spirit of the Lord was so close that there was no doubt in anyone’s mind. It was a wonderful experience, one that none of us shall ever forget.”[24]

An important component of President Fyans’s approach was his role as a delegator. He would help the member understand the principles involved and, after those principles were learned, get out of the way. Missionaries and members alike remember that he often began talks with a quote of Goethe, “Treat a man as he is and he will remain as he is. Treat a man as he can and should be, and he will become as he can and should be.” He strongly believed that once someone was in a position of responsibility, he would be blessed to accomplish the job. President Moyle had taught him that concept before leaving Salt Lake: “Don’t you ever ask a question of Salt Lake unless you want an answer. Now you go down and run that mission. Go get it done.”[25] President Fyans put his complete trust in the missionaries and members, believing the Lord would bless them with the ability and skill to do any task they were asked.

Néstor Vogler, the district president in Montevideo, had an experience that had to do with this method. The district presidency wanted to have a youth conference and went to President Fyans for help and advice because they had never done one before. The previous conferences had always been organized by missionaries. President Fyans put his arm around President Vogler and said, “Brother Vogler, if there has been a time in the history of this mission for this to happen, it is now. Go do it!” President Vogler was surprised there would be such confidence in him and his counselors, saying, “He gave me so much confidence. That was one of his gifts, to instill confidence.” The district presidency organized a youth conference that was considered a success.[26]

Elder Tuttle expressed his admiration of President Fyans: “You have made an outstanding record. You have taken the leadership among the South American Mission with typical humility and a desire to share all that you have and know. This ever marks you as one of the men of the earth.”[27] David Hoopes stated, “I think President Tuttle recognized President Fyans’s genius at organization at planning and implementing plans.”

The calling of a local leader in Asunción, Paraguay, again was unusual. The branches were small and beginning to grow. An American and former missionary from Argentina, Robert Wells, was in Paraguay working as an assistant manager of an international bank. He was one of the branch presidents. On April 30, 1961, in a district conference, President Wells was set apart as district president and assigned as a special assistant to President Fyans to help run the mission in Paraguay. When on the Saturday before the conference President Fyans explained that he wanted to install a local branch presidency, President Wells said, “No, not these people. I love them. I know them very well, but no way could these people run the branches or the district. . . . They just don’t know that much, and they don’t have the dedication, they don’t have the initiative, they don’t have the Spirit.” President Fyans listened to his advice and said they were going to do it anyway. President Wells was worried. He agreed to go along with the change because he believed Fyans was the one who received the inspiration for the mission. President Wells recommended the strongest three men in the branch but continued to question the advisability of the change: “I just thought that he [Fyans] was totally a dreamer, that no way was this going to work.”

President Fyans asked President Wells to fast and pray with him that evening. During the evening Fyans began to have doubts and did not sleep much. He thought, “Tom, how stupid can you be? You moved contrary to the counsel of someone who knows these people and who’s been all this time in Latin America.” In the morning President Wells was a little more positive, but not much more, saying, “Well, this will be a good experience. It’ll be an experiment. In any case, we can always pick up the pieces.” Three men were called and sustained in the conference, and President Wells could not believe the change that immediately came over the new presidency: “I saw a miracle. I actually saw a miracle.” He had worked with the men for years and watched as they humbly struggled with their assignments, “But that day after President Fyans had them sustained and then called on them each to speak, they were magnified. They were different. I’ve never seen anything quite like it before since each one of these men gave a powerful sermon, as well as testimony.” President Wells saw the power of the mantle on those who were called. In the next few months, things continued to improve in the branch. Attendance at meetings improved, and home teaching visits increased. President Wells stated, “It was a great lesson for me.”[28]

By the end of April, all the branches in Uruguay and Paraguay had local presidents with the exception of three, which were recently opened and had no men with the priesthood who could function as branch president. But having a person in the position of branch president and then having someone who knew how to function in that position was a different story. These men had to be trained. At first their training came in the form of vocal instruction from President Fyans or the missionaries. But more was needed, so President Fyans went back to his couch for more ideas. The result was a missionwide branch presidents’ conference to be held in Montevideo on May 27–28, 1961. This was to be an event to be remembered. For more than two months, he and the district presidents planned every detail of the meetings. All the branches in Uruguay were represented, most with four members of the branch presidency in attendance, and President Fyans wrote, “What a thrill to see the chapel nearly filled with these humble men, holders of the holy priesthood, united in love, devotion, and with a desire to serve.”[29]

All day Saturday branch presidents were taught, mostly by the missionary district leaders. The instruction included a discussion of all aspects of their call, such as how to train, how to build friendships, and how to call someone to a position of responsibility. They then broke into small groups to practice what was learned. That evening President Fyans made a surprise challenge. He asked them “to work to replace themselves. He said that he hoped that if another meeting were to be held a year from that date, that none of the same brethren would be in attendance. . . . They knew that he was calling them to exert themselves in the work as they had never done before. He was calling them to convert new men who would be capable of taking over their positions.”[30] That concept of preparing for their own release was an important part of President Fyans’s philosophy throughout his mission.

Sunday was spent talking about missionary work. At the end President Fyans announced he had been invited to talk about member organization at the Church worldwide mission presidents’ conference to be held the following month. He said he would be talking about them. The final event of the conference was a testimony meeting in which those present expressed feelings about their callings in the branches and the training received at the meetings. The conference adjourned, and the branch presidents took their suitcases and bedrolls and went home. Afterward the mission staff met, and President Fyans said they “had seen a ‘modern miracle’ as these men realized the great job ahead of them and had there dedicated themselves to forwarding of the Lord’s work in their individual branches.”[31]

The next step was to place local members in the leadership of the districts. Again missionaries occupied these positions, except in Montevideo. He asked six branch presidents to come to Montevideo for special training. They did not know that the training they were to receive was to prepare them to serve in district presidencies. The methodology was the same as in the branch presidency training. They arrived by noon, were fed by Sister Fyans, and attended sessions through Sunday morning. The training ended with a testimony meeting. They talked about how branches were organized and the activities of administration of local units. Then President Fyans discussed something that most in attendance considered an impossibility, what it would take to become a stake. The different steps were discussed, and a vision of Church organization was opened up to these men. As soon as the training was finished, the men went home, only to get called within a few weeks to be district leaders.[32]

Not only was this training valuable to these men in their Church callings, it was also beneficial in their professions. The branch president from Durazno was a trucker. After his branch presidency training, the truckers in the region organized and formed a local labor association and this branch president was elected president. While attending the convention of the national association of truckers, he was active in making suggestions. In that meeting he was named head of the national organization. In analyzing how that happened, he realized he had obtained the information and methods he used in these training meetings.[33]

President Fyans’s approach to missionary work was similar to his strategy for the administration of the branches and districts. He did not change much of the methodology of his predecessor. The only significant change was to have the missionaries memorize the new lessons introduced at the world missionary conference. Fyans was not as concerned with methods of missionary work as with giving them more time to proselyte. He felt the missionaries needed only the general principles of missionary work to have success.[34]

This was to happen through his Channel 5 program. The primary purpose of this program was to improve the branches to a point that nonmembers would be attracted to the Church. The term channel was used because the focus of the program was to be in five areas or channels of training for members, missionaries, and leaders. The five channels were member leader training, missionary leader training, creating an active proselyting membership, training an effective missionary force, and missionary and member involvement in bringing friends to the Church. A detailed plan of action was developed in which these five areas received a focus in the branches throughout the year. The expected result of the program was increased baptisms.[35]

Did the objective of getting missionaries out of administrative positions and into proselyting activities work? The goal of doubling of the mission population was not reached, but the 1,120 baptized in 1961 more than doubled the number baptized the previous year. President Fyans was pleased with the results but felt the mission could do better. His emphasis for the rest of his mission followed the pattern established during this first year.

Six Steps to Stakehood

During his first year in Uruguay, Fyans developed the most important program for his three years as mission president. His program became not only a guide for the other missions of South America but was adopted in many other parts of the world. Focusing on President Moyle’s challenge to prepare the Church in Montevideo to become a stake, he developed a method to accomplish this goal. That plan was the “Six Steps to Stakehood.”

The formation of a stake is an important milestone in the evolution of the Church. Historian James Allen stated: “Church leaders have pointed out that ‘stakehood’ is the ideal, the goal, for which every mission district is being prepared. Stakes cannot be organized until there is sufficient membership and trained leaders, the problem of distance and communication have been overcome, and the Church program is operating fully within the district. The organization of a stake in a given area represents not only growth in membership, but also a maturing in the full Church program and a development in spirituality.”[36]

The organization of a stake would mean the Church in Uruguay had reached a level of maturity on par with the Church organization in Utah. It would signify that the Church in Uruguay had the leadership and proper organization so that the tutelage of the mission and the American mission president was not necessary. When a stake was organized, it indicated the local leaders had developed enough to interact directly with the Church leadership in Salt Lake City. The Church in Uruguay would no longer be a lesser appendage. In the scriptural sense, the stake was the essential gathering unit of Zion, where the honest in heart were to be brought together. In the mind of Elder Tuttle, President Fyans, and the other leaders of the missions, the organization of stakes in South America was the chief goal to which they were working. It was the key act that would bring the Church in South America into the fold of the entire Church. It was a goal that had not appeared possible by their predecessors with so few members and so many untrained leaders. It became the focus of this group of mission presidents.

Coming up with the plan for stakehood took many hours, but in reality it was a simple plan. It was illustrated by looking at how an organization grows. Fyans often used the example of the organization of Primary to show how the plan worked. In the beginning the Primary is fairly weak, so it is completely staffed by the small leadership of the organization, first with a president and, when possible, two counselors and a secretary. They are not only the leaders but also the teachers. The leaders at this point are overburdened with responsibility. With training they catch the vision and work to call others to replace themselves as the teachers. Eventually the president of the Primary may be called into a higher position of leadership, generally in the district, which is probably also weak. Again she becomes involved both in administration and teaching. Her replacement at the branch level is often one of the counselors, who is replaced by one who is called to teach. The process begins anew to find someone to replace them as teachers. This process operates until a complete organization becomes a reality as leaders and teachers work to find someone to replace themselves. It is a very simple process but important in that leaders are constantly involved in training.[37]

Following this concept, the first step toward stakehood was the formation of a district organization with a skeleton structure, including a president, a secretary, and supervisors for each auxiliary organization, such as Sunday School, Primary, family history, Mutual, and Relief Society. The supervisors were not line priesthood leaders, but leaders who could assist and teach the branch leaders in their responsibilities. All the district leaders visited the branches, trained the organization leaders, and worked with issues and problems. It was an initial step that transferred responsibility for supervision and training from the American missionary to the local members. The effect on the branches was significant because new local leaders had to be called into branch positions to replace those who moved to the district organization, thus putting into effect the idea of replacing oneself in the organization.[38]

The second step was to start replacing the organization by calling two counselors to the district presidency. These men were in positions in the branches, mostly branch presidents who came to their new job with some experience and training in leadership. At this point the responsibilities for supervision of the different auxiliaries and functions were divided between the president and two counselors. Leaders with responsibility over the auxiliary organizations called during the first phase continued to supervise the same organizations but were placed under line authority of the district presidency.

Development of the auxiliary organizations was the next step. During this step, district presidents and superintendencies were called for Sunday School, Primary, family history, Mutual, and Relief Society. The district organizations were strengthened by calling not only a president but two counselors and a secretary. With this additional organization, the training and supervision of the auxiliaries in the branches would be transferred from the mission to the district, thus establishing complete local supervision of the district leaders. This was an important step because it eliminated mission supervision of the local units.

Forming a district council became the fourth step. This council consisted of six priesthood holders who supervised the auxiliary organizations of the branches. In the past a counselor in the district presidency had supervised these organizations. The district president continued training others but was further removed from the actual supervision of the auxiliary units of the branches. With each step, the district leadership received added responsibility and more supervision of home teaching, retention of new converts, priesthood, and music.

The fifth step was to officially organize the district boards of the different auxiliaries by calling additional persons to act in the different functions of a regional organization. President Fyans had been working on strengthening the auxiliaries from the beginning of his presidency. Shortly after arriving, President Fyans organized mission boards for the auxiliaries to supervise and train the district and branch leaders. The first organized was the Primary under the leadership of a young Uruguayan member, Carmen Vigo. On May 20, 1961, Fyans invited a select group of members all from Montevideo to come to a meeting at the mission home, during which the responsibilities of the Primary board were explained. At first there were concerns and uncertainty, but with time came acceptance of the new organization. During the testimonies at the end of the meeting, President Fyans stated, “There was a lump in every throat, a tear in every eye, and a burning within each heart.” The makeup of the groups was somewhat unusual. One person called to the board was a nonmember married to a member, and another had been a member less than two months. The amount of time in the Church was not a concern for President Fyans. Often a husband was called to a position of responsibility soon after his baptism if their wife had been in the Church. His expectation was that he had already been participating in the Church through their spouse: “They had to have a testimony, administrative ability, personality, and some aggressiveness.”[39]

The Mutual Improvement Association mission board for the youth was organized two days later, and the Relief Society three days afterward, which occurred in what President Fyans described as the “most spiritual meeting held at the mission home.” For two years these boards served double duty as both the Mission and Montevideo district boards until two separate groups of boards were formed.[40] When this happened, they became members of boards with responsibility for working on different aspects of the organizations. With this step the boards were functioning as they would in a stake organization, having complete responsibility for training and supervising the branch auxiliaries.

President Fyans also formed a mission auxiliary board consisting of American couples working with the building construction program. The purpose of this board was to provide advice to the mission boards by Americans who had experience in similar positions in the United States. A further reason for this board was to help integrate the Americans into the Uruguayan Church organizations. This board worked primarily with the mission council, with the responsibility to train the Uruguayan members. President Fyans responded to the question of why he had formed this group: “A stake will be formed soon. The people must be trained to sustain themselves. They must be trained throughout the mission, for within a few years there will be stakes organized all over the country.” He believed the Americans could be a significant help because they had experience and knew how the Church was supposed to function.[41]

The sixth and final step was to augment the district council from six to twelve priesthood holders, resulting in a further division of responsibilities of the activities of the district. With this step complete and with the accompanying growth and development of the individual branches in the area, President Fyans believed the district would be ready for stakehood. At this point the district organization would be functioning the same as a stake and all that would be required would be a name change.

These two plans, Channel 5 and Six Steps to Stakehood, so impressed Elder Tuttle that he asked President Fyans to make a presentation at the mission presidents’ conference held in Lima, Peru, in June 1962. Elder Tuttle hoped all the missions would adopt the same programs. President Fyans said, “President Tuttle suggested that all mission presidents become thoroughly acquainted with the plan so that they can put it into effect in their respective missions as quickly as possible.” The response by the presidents to the Six Steps to Stakehood was positive, but some concerns were expressed for the Channel 5 program. Elder Tuttle reported that “again the member missionary program was presented and more confusion resulted.” President Bangerter was frustrated that the focus of the program was not on the proselyting activities of the missionaries but on member organization. He stated, “We continued with the time supposedly devoted to proselyting, but with almost all of it in the direction of organization of member-leadership in our missions.” President Bangerter felt the programs were too complicated and contained too much organizational detail. He suggested less structure and more reliance on the Spirit. The Channel 5 program did not find much acceptance outside Uruguay.[42]

President Fyans wanted all of the districts in Uruguay actively working on his goals but realistically felt that only the Montevideo District was strong enough to become a stake by the end of 1964. The other districts would follow as soon as they were ready.

Trip to Utah

The different boards of the mission worked with varying degrees of success. President Fyans was pleased with the success but frustrated that there was an occasional lack of understanding of what he was trying to do. In 1963 he decided to do something he felt would dramatically increase the speed in which the districts were organizing into stakes. He perceived that part of the struggle of the leaders was that they were working to create something completely foreign to them. They had no idea how a stake functioned because they had never seen one. They listened to the descriptions the American families gave, but had little concept of the Church outside of their small branches in Uruguay.

In fall 1962, Darrel Chase, president of Utah State University, and his assistant, Austin Haws, were in Montevideo to check on programs the university had established in Uruguay. Chase asked President Fyans how they could help the mission. President Fyans response was to “get somebody from down here to have the vision of the Church, what it really is.” A few weeks later President Fyans received a letter from Chase with the proposal, “Our high priests quorum here would like to sponsor a person of your choice to come to general conference.”[43] Their only requirement was that the person go to Logan, Utah, to attend regular meetings where they could experience the Church in a typical setting. President Fyans felt that having one person go to Utah would be good but it would be better to give more members the same experience. When his missionaries learned about the offer from President Chase, they made a commitment to forgo spending money on extra non-missionary activities and use the money to support an additional visit. Then some parents of the missionaries in Los Angeles and Salt Lake City learned of the project and came up with enough additional money to send a third member.

In the middle of March, the office staff met together and determined who would go. President Fyans then traveled to the northern city of Rivera, where he informed district president Juan Echizarto that he had been chosen. Later at a special dinner in Montevideo, they informed the central district president, Vicente Rubio, he would also go. Also in attendance was César Guerra, a counselor in the district and full-time translator for the Church. He knew of the planned visits but thought only two would be going. When President Fyans announced that Guerra could go too, he was so surprised that he threw his napkin into the air and walked out of the room without saying a word. All in attendance were concerned. Upon returning, Guerra exclaimed, “I just had to pinch myself and see if it was a dream.” Guerra was an important addition to the group because he was the only one who spoke English. All three were grateful for this privilege of a lifetime.[44]

President Fyans helped put together the itinerary, including asking Elder Boyd K. Packer, one of the Assistants to the Twelve, to help them in Salt Lake City. They arrived in Utah on April 3, where they visited Welfare Square, Brigham Young University, the Language Training Mission, and seminary and institute classes. Two of the three went through the temple, where they were endowed. They attended all of the sessions of general conference and then went to Logan, where they attended several meetings including a high council meeting. They went to a stake conference in Bountiful, Utah, and then to Los Angeles, where they visited the temple and returned home on April 16. In a meeting with Uruguayan district leaders, they excitedly told of their experiences. Guerra made sure all knew of the importance and reason for the trip: “We did not visit the United States, we visited the Church.”[45] The trip had a more lasting effect than most expected: “The brethren saw many things, but what they felt and are now doing is more significant. They saw dedicated Church members and now feel the desire to be more dedicated. . . . They realize that unwavering sacrifice is necessary to accomplish the Lord’s purposes. More important, they realize that the kingdom of God is upon the earth, and they are striving with new vision and dedication to lift the level of the entire mission.”[46]

For months after the visit, these three men continued to talk to the leadership of the mission about what they had experienced. The effect of the visit on the mission was significant. In a district meeting held in Montevideo on June 2, 1963, both Elder Tuttle and President Fyans were greatly impressed with the way the local leaders conducted the meeting. Elder Tuttle stated it was a historic meeting, and President Fyans said it was a turning point in the history of the mission: “The local leaders instructed themselves. It was a marvelous meeting. We have come to a plateau as far as local leaders are concerned. Most of the basic creative work is behind us; . . . we can now concentrate on administration.”[47]

During this time several tragedies stuck close to home. On May 19, 1963, they received a telegram from President Nicolaysen of the Andes Mission that one of their elders, on his way home from his mission, was missing in Peru. Elder Phillip Styler and a companion had been climbing Hauayne Picchu, the peak next to the famous Machu Picchu, when they briefly became separated and Styler disappeared. After several days of looking, Elder Styler’s body was found several miles downstream from the place he had slipped and fallen into the river. The incident left the entire mission somber and sad. Then on July 11, 1963, one of the Church construction managers and counselor in the mission, Samuel Boren and his wife were in a nighttime boat crossing between Buenos Aires and Montevideo when a fierce storm came up and sunk the boat. For hours President Fyans did not know the fate of their friends. Luckily, the Borens were able to avoid drowning by clinging to some wood and were rescued hours after the accident. Unfortunately, many on the boat were not so fortunate and many died.[48] Finally on October 30, 1963, a tornado stuck the interior Uruguayan city of Trinidad and many members were left homeless. Help in the form of food, clothing, and bedding was soon on its way from Salt Lake City.[49]

President Fyans was not sure how long he would be in Uruguay because at that time mission presidents were not given a specific length of time to serve. In February 1963, during the mission tour with President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency, Fyans woke up early in the morning with so much pain in his upper back that he rolled on the floor in agony. The diagnosis was that he was passing a kidney stone, and they seriously considered sending him to Miami for an operation. The stone passed, however, and he returned back to normal. He appreciated a blessing by President Brown and Elder Tuttle. A month later he was informed by Elder Tuttle that his mission would be for three years and that he would be returning home in July 1963. The Fyanses decided to send their two oldest daughters home early to the United States so their oldest, Carol, could get some schooling unavailable in Uruguay and Kathy could graduate from high school in the United States. Later in May, however, Elder Spencer W. Kimball of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles visited Uruguay and asked if they could remain an additional year. For a few minutes Helen, who had just sent her two daughters to the United States, was disappointed because it meant not seeing them for a year and a half. That feeling soon turned to appreciation when she realized that they would have more time to work on goals not yet accomplished in the mission.[50]

That fall President Fyans and Elder Tuttle felt that the leadership of the district in Montevideo was ready to become a stake. They submitted papers to Church headquarters with the request for stake organization. They were disappointed on February 19, 1964, when Elder Tuttle received a letter from Salt Lake City indicating the proposal had been turned down by the Quorum of the Twelve. Elder Tuttle expressed great sadness at this turn of events: “This was too bad; a lot of work has gone into it at this point, but we shall continue to work on it until there is a full hearing of the case.”[51] President Fyans decided to continue to work as if he had not received the bad news. He hoped that with more work the district would be ready to become a stake later in the year just before he returned home.

President Fyans worked on the last of the six steps to organize a stake: detailed training of the leaders of the auxiliaries. He developed elaborated manuals of instruction for each auxiliary that included information on all aspects of their calling. They began inviting the auxiliaries to come to Montevideo as was done earlier with the branch and district presidencies. The mission home fondly became known as “Helen’s Hotel” because almost every week groups arrived with sleeping bags and mats to sleep on the floors. Helen Fyans had the task of feeding the groups. Her response to the extra work was positive, “I loved it.”[52]

President Fyans was sure this additional work made the district in Montevideo ready to be organized as a stake, and on May 1, 1964, he submitted a proposal to Elder Spencer W. Kimball, before his visit to Uruguay. In the report President Fyans described in great detail the organization of the district, including indication of age, family status, and talents of the leaders. There were 195 Melchizedek Priesthood holders, the district had 30 percent home teaching, and 25 percent of the membership paid a full tithing. The members owned a total of fifteen automobiles and twenty-five motor scooters. He did not state the number of bicycles, which was the primary mode of transportation in many parts of the country. Did President Fyans think they were ready for stakehood? He said, “These members are wonderful, and they will not be blinded when placed in the full light of the restored gospel but will be warmed by its glow and stimulated to growth by its power.”[53]

In anticipation of Elder Kimball’s visit, President Fyans had another goal. All large meetings had to be held in rented halls because the Church did not own a large enough building. That problem was about to be remedied with the construction of a large chapel in the Malvín Branch. Fyans decided he did not want to rent a hall for the conference but to hold the meeting in the chapel. The only problem was that the building was not anywhere near completion and would not be ready by the time of the visit. On May 3, 1964, Fyans visited the construction site and talked to members of the Church Building Committee. After that visit he felt that with a significant effort by the members, the chapel could be finished enough to at least hold the meeting. He presented a plan for finishing what would be necessary by May 23, twenty days from that date. Part of his reasoning was to increase membership help in the construction of the chapels. The building committee, which included members of the branch, thought it impossible.

President Fyans thought differently: “They had not been against the idea because of stubbornness but because of an honest conviction of the near impossibility of the undertaking.” He convinced the construction supervisors to try. They organized large crews of labor missionaries from around the country to work on the building. A crew of construction missionaries from Brazil even came to their aid. The eight branches in the city supplied large numbers of members to help on the building throughout the day. Many with jobs took vacation time to work on the chapel. Nonmembers also helped on the building. At one time, more than a hundred people were part of a brick-passing line. Within two weeks, a building that had been a “network of wooden supports, a half-built wall in the chapel and dirt floor everywhere” was completed enough to meet in. With an incredible effort, the building was readied for the conference. President Fyans described the decorations. The chapel “was decorated with plants and flowers and with green rugs, and benches that has been brought in from all the branches of the Capital District. In the rear of the chapel, people sat on planks covered with paper and supported by blocks used in the construction of the chapel. Although the beautiful interior decorations usually found in the chapels were missing, the decorations added a feeling of warmth and beauty.”[54]

Left to right: Luis Giannattasio, president of Uruguay, meets with Elder Spencer W. Kimball, Thomas Fyans, and Elder Tuttle, May 24, 1964.

Left to right: Luis Giannattasio, president of Uruguay, meets with Elder Spencer W. Kimball, Thomas Fyans, and Elder Tuttle, May 24, 1964.

Elder Kimball was pleased with the efforts. President Fyans stated, “Although incomplete, the Malvín Chapel was a beautiful sight for the conference session.” All who had worked on the construction were asked to stand, and many came to their feet. It was an impressive sight. Construction missionaries from four different countries—Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, and the United States—spoke in Spanish, Portuguese, and English.[55] Elder Kimball praised the work to get the district ready for the conference as well as preparation to become a stake. His comment was, “Tom, this has all the qualifications of a stake. I wish we could make a stake today.” Fyans, with his characteristic lack of concern for bureaucratic approval, asked, “Why don’t we?” He was informed that they did not have the required permission from the First Presidency.[56]

The main delay in organizing a stake was not in Uruguay but in Salt Lake City. When Elder Kimball returned home, he wrote to say that the meetings of the group that approved the formation of stakes had been discontinued for the summer and would not be held until after the Fyanses returned to the United States. With this additional time, Elder Kimball asked for a significant amount of additional information to be used to support the request for stakehood. The information was needed because there were some on the committee who were not in favor of organizing stakes outside the United States and needed to be convinced. Elder Kimball wrote: “I do not know what their reaction will be now, but some of the Brethren have been quite opposed to the creation of stakes in foreign countries until there is a great maturity on the part of the local people. It is my hope that with your help when you have returned, that I may be able to make a presentation to the Brethren to convince them that the group in Montevideo are mature enough to carry on the work. You have done a magnificent service in preparing them.”[57]

In a subsequent letter, Elder Kimball asked for a detailed breakdown of the statistical information on the Capital District. The additional requested information centered on what was weak in the district. The request included additional information about the young men in the area, such as how many of the unmarried young men, eighteen or over, had not served a mission, either full time or construction. He wanted not only the number, but a list of names and reasons they had not served. He asked for additional information on tithe payers. Elder Kimball had gone over President Fyans’s report with such detail that he noticed that two members of the district council were not on the list of tithe payers. He wanted to know why. He noticed that one of the counselors in a branch presidency was also the sports director for the youth organization of the district. Why? He had questions on finances, home teaching, leadership development, and percentage of attendance at all meetings. The request for additional information suggested a concern on the part of Elder Kimball as to how the request would be received by the committee in Salt Lake City.

After receiving the letter, President Fyans began to work on some of the concerns with a question to his leaders: “How prepared are we to become a stake?” He talked to his leaders about the calling of additional local missionaries and increasing the number of tithe payers.[58]

During the last few months of President Fyans’s mission, the highest number of baptisms per month in the history of the mission was recorded. The Fyanses prepared to return to the United States. In June they celebrated the baptism of the ten thousandth member of the Church in Uruguay. They prepared a visual presentation, complete with posters and pictures, for the First Presidency describing the events of his presidency. His report would contain a request for three things, stake organizations, Church schools, and a temple. A number of going-away parties were held, and many tears were shed. President Fyans said his greatest joy was that the leadership of the branches and districts was in the hands of the local members: “I go to a conference and sit on the sidelines.”[59] With a feeling of satisfaction he contemplated fulfilling President Moyle’s goal of “laying a foundation for the organization of a stake in Montevideo.”

A New Mission President

The Fyanses left Uruguay on July 26, a few days before James E. Barton, the new president, arrived. However, President Fyans met with the Bartons in New York City and discussed the mission. President Barton was different from President Fyans. He was about the same age, but was a scientist and teacher, not a businessman. He had a PhD in irrigation engineering from Colorado State University and at the time of his call was chairman of the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of New Mexico. President Fyans liked him. “I was very impressed. He has a wonderful spirit and exhibited a great desire to touch the hearts of the people.” It was President Barton’s qualities of love and concern for which he was to be appreciated and remembered by the members.[60]

President Barton had unique methodologies because of his training as an engineer, that affected the way he directed the mission. Elder Kimball had suggested that he continue with President Fyans’s programs, which he did, but changed some of the emphases. He had been told by Elder Kimball that his primary responsibility was to missionary efforts, and that was where he put his focus. After his first tour of the mission, he became concerned that some of those being baptized were not being adequately prepared. In his first meeting to the mission council, he suggested a need for emphasis on the teaching process of converts. The missionaries needed to make sure the converts were being prepared properly. The convert should “not be baptized immediately on expressing a desire, but should be taught the requirements etc. before baptism. . . . All six lessons should be taught the investigator either before or after he is a member.”[61]

President Barton also reinstituted the practice of distributing missionary tracts. President Fyans’s Channel 5 program was designed to eliminate the need for tracting because the members would be involved in finding families for the missionaries to teach. President Barton felt the missionaries benefited from the experience of tracting because it helped instill a stronger work ethic: “Some missionaries did not work as hard as they had thought they did and were not as dedicated as he thought they would be.”[62]

He also began to strongly push a program that Elder Tuttle had recently suggested would result in stronger branches—teaching only families. Concerned that the number of baptisms of complete families was small, Elder Tuttle had asked that the missionaries focus on teaching complete families. They were discouraged from teaching lessons if the father was not present. Elder Tuttle felt that the result might be a decrease in baptisms but that the branches would be strengthened by the infusion of strong families into the organizations. In April 1965 the number baptized in the mission dropped to below one hundred, the first time this had happened in Uruguay since March 1962. The suggested reasons was the push to baptize families but also the increase in the activities of the opposition. President Barton stated, “Satan is not going to sit by and see the work go forward.”[63]

President Barton was also careful about the local organization of districts. He believed in allowing time for the member organizations to mature. The fast movement of members into positions of leadership was fine, but they needed time to learn how to function in those positions. He was not as concerned about pushing for the organization of a stake as he was in strengthening the districts. He heeded Elder Kimball’s counsel and direction as he worked to train and assist the members in fulfilling their responsibilities. The organization of the first stake in Uruguay did not occur until November 12, 1967, two years after President Barton had been in Uruguay. Providentially, President Fyans was there on assignment for the Church to work with translation of Church manuals. At the moment of organization, Elder Kimball had his usual translator sit down and asked President Fyans to stand by him and translate, saying, “Tom, you and I are going to form the first stake in Uruguay.”[64]

Conclusion

The dream that Uruguay would become the center of the Church in South America did not come to fruition. Temples were built in almost all other countries of South America before one was finally dedicated in 2000, on the spot in Uruguay where it had been envisioned by President Williams and Elder Tuttle. The political calm and stability of Uruguay as the Switzerland of South America suffered serious disruptions with the activities of a violent and dynamic revolutionary group called the Tupac Amaros, which destabilized the country in the late 1960s by a series of violent attacks on different sectors of the country. The political rhetoric of the time resulted in significant polarization of political groups in the country. The resultant takeover of the country by the military in February 1973 changed the political environment. These events ended a tradition of democracy and freedom in Uruguay that has yet to recuperate, even after democratic elections were again held in November 1984.

During the late 1960s, some politically active citizens, including a few members of the Church, suffered because of their activities and a few left the country for their protection. The political insecurity in the country found its way into the Church as political rhetoric was occasionally spoken in Church. Conflicts within the Church during the military takeover, again primarily in Montevideo, seriously weakened the Church and some members were exiled or placed in prison. These political differences weakened the Church, particularly in Montevideo, occasionally causing serious rifts in the membership.

In part, Uruguay’s position as the center of the Church in South America did not materialize because the Church was divided into larger units called areas. Uruguay became part of the South America South Area with headquarters in Argentina. In recent years, the creation of a second mission, the building of a temple, and the growth in the number of baptisms has strengthened the Church, and the future of the Church looks bright there.[65]

Notes

[1] President Fyans describes his mission call in the personal history of his mission, under the date September 23, 1960; in Thomas Fyans’s possession. It will be referred to as “Fyans History.”

[2] W. H. Hudson, The Purple Land (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1916), 10–12.

[3] J. M. G. Kleinpenning, The Purple Land: A Historical Geography of Rural Uruguay, 1500–1915 (Amsterdam: CEDLA, 1995), 107–10.

[4] For a history of Uruguay, see Washington Reyes Abadie, Crónica general del Uruguay (Montevideo: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental, 1998).

[5] See Milton I. Vanger, The Model Country: José Batlle y Ordeñez of Uruguay, 1907–1915 (Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 1980).

[6] Information for this biographical summary is taken from Frederick S. Williams and Frederick G. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree (Fullerton, CA: Et Cetera, 1987).

[7] Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak, 232.

[8] Gordon Irving, “Numerical Strength and Geographical Distribution of the LDS Missionary Force, 1830–1974,” Task Papers in LDS History, no. 1, April 1975, 23, 26, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[9] Preston James, Latin America, 5th ed. (New York: Wiley, 1960), 600, 668, 684.