The Promise and the Destiny

Mark L. Grover, "The Promise and the Destiny," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008) 312–36.

Sister Tuttle loved to see Elder Tuttle on his horse, but it was a rare sight after they moved to South America. Elder Tuttle was a farm boy at heart who was not very comfortable in the city with all the people. He felt more at home with farm animals; they could be trained, and once they learned they seemed to obey. Humans had to be taught, prodded, and helped along, and even then they did not always obey. Maybe that was why he was more comfortable with his horse.

Missionaries from the Uruguayan Mission found out how much he loved horses and on May 1, 1962, presented him first with a saddle, then a bridle, and finally a horse. It was an unusual present. At the time he did not have a place for it and did not know where to get feed in the middle of a major city. However, he soon turned part of the land between the homes on the block into a corral. There were some unexpected struggles, such as the time when the horse was stolen and Sister Tuttle, after spotting the horse, ran after the thieves. That horse caused the family some concerns but was a joy to Elder Tuttle, and the image of Elder Tuttle sitting on a horse in the backyard of the mission home in Carrasco, Uruguay, was reassuring.[1]

The problem was that Elder Tuttle was not in Montevideo much, and when he was, he was busy working in the office. Being president of the South American Mission was not conducive to spending time with the horse. Sometimes Elder Tuttle would bridle and saddle the horse, mount it, and conduct his business from the back of that horse. He mostly did interviews and talks with his children or missionaries, who, if it was the first time, were a little uncomfortable with the arrangement of his office furniture. His advice had an interesting flavor when given from the back of the horse.[2]

Elder Tuttle on his horse

Elder Tuttle on his horse

One could wonder how a farm boy from Manti, Utah, who felt more comfortable riding horses, trimming fruit trees, or fixing a faucet, handled his highly administrative position and responsibility for large sums of money and the lives of hundreds of missionaries. It was not easy. One day he wrote in his diary, “People have sorrows that sadden others’ lives. I sometimes feel helpless. I am tired.” But another day he wrote, “All is well; the Lord is good! Busy catching up on correspondence.”[3] Perhaps his insecurity of being a farm boy was reflected in Sister Tuttle’s statement: “I can’t believe this is happening to me.”[4]

But Elder Tuttle did not feel too insecure. There was a feeling of confidence about him that let others know he believed he could do anything with the Lord’s help. That feeling did not come from natural confidence or arrogance; he had experiences that trained him to be positive. His war experiences, when he was surrounded by death and destruction and yet was able to survive, helped him develop the ability to confront anything. His years of experience in front of a classroom of teenage students also did its part in providing experience. Then his years of administration in the seminary and institute program of the Church added to that confidence.

That was not the only source of his assurance. To understand Elder Tuttle, we must understand his relationship with God. He knew that God would be there to help him. Elder Tuttle had been called to labor, and he was going to do it. He knew he had to work, and if he did so he could accomplish what was being asked. In an April 15, 1962, talk to his home ward in Pleasant Grove, Utah, he spoke about his call to South America: “One reason I am there is to fulfill prophecy. None is automatically fulfilled without work! The hastening process is to be hastened by our efforts.”[5]

As a result, the move to South America to live in a country that functioned in a language he did not understand was not particularly difficult. From the beginning the Tuttles loved Uruguay. On Sister Tuttle’s first full day, she exclaimed, “This is a beautiful country.” It did not take long until Uruguay was their home. In the fall of 1962, upon leaving Salt Lake City after attending general conference, Sister Tuttle stated her pleasure to return to Uruguay: “I am getting as excited about reaching home in Montevideo as I was to come to conference. I feel so privileged to be here. . . . We are thrilled and happy and humbled in our present assignment.”[6]

That feeling persisted throughout their entire assignment. In a letter written near the end of 1963 to President Hugh B. Brown, Elder Tuttle said, “I repeat, that while I will gladly do whatever you brethren desire, for myself and family, we prefer to stay here as long as we can be of service to the program.” In a similar letter to President Brown a year later, Elder Tuttle expressed the same feeling: “We write on this occasion to express the hope that we may be permitted to stay in these lands for at least another year or more. I’m not unaware that there are pressures created in other places and I receive occasionally expressed sentiment about my not being in Salt Lake City. . . . I would like to remain here long enough to get schools under way in all of the South American Missions.”[7]

President Tuttle at the airport.

So what attracted Elder Tuttle to South America? It was not an easy assignment; South America is large and diverse. Elder Tuttle spent a good percentage of his time on the road. He expended a lot of time waiting in airports and sleeping in unfamiliar beds. When he arrived at his destination, he was always busy attending conferences or conferring with mission presidents, members, or missionaries. Often the topic of conversation was on difficult issues not easily resolved. He was away from his family much of the time. One very touching experience in family home evening emphasized this difficult life as a vagabond. His young daughter, Lisa, after enjoying having her father at home, suggested a simple way of keeping him there: “We should tie daddy up! Why? So he won’t go away so much.”[8]

Sister Tuttle explained her husband’s faith in a letter to her parents: “Ted is so full of faith and love for the gospel and the people here, I know that if I will do my part the work will go forward rapidly here.”[9] Yet Elder Tuttle was always aware of his weaknesses and occasionally his lack of capabilities. He did not doubt the Lord, but he was surprised at his role. Recognizing that he was a farm boy from Manti made it difficult for him to imagine having such responsibilities: “But I can see occasionally—not frequently, but occasionally—where there is some kind of contribution I can make that hopeful will be acceptable to the Lord and to the people. But I feel so humble amidst all of these mighty brethren that I see around me that it isn’t always a comfortable feeling to try and fill this position.”[10]

South America

Elder Tuttle began a major reformation in South America. He knew he was there with President Henry D. Moyle’s blessing. Elder Tuttle was to do to South America what President Moyle was trying to do to the Church in general. Elder Tuttle stated in 1972, “When he [Moyle] became a member of the First Presidency he was given the assignment of missionary work, which was moving very slowly at the time. . . . He took the work and singlehandedly raised it up to a point of high productivity in many areas of the world which otherwise would right now still be missions instead of stakes.”[11]

By sending Elder Tuttle to South America, President Moyle hoped the same thing would happen in South America. Elder Tuttle’s job was to establish closer supervision in an area believed to have great potential.

During his first visit near the end of 1960, after realizing he would likely be serving in South America in some capacity, Elder Tuttle immediately recognized what needed to be done. He felt that proselyting and missionary work was going relatively well, but what he saw in the branches concerned him. The congregations consisted primarily of females, teenagers, and young children. He saw members struggling with poverty. There was limited leadership training, and he saw limited potential for priesthood leadership. He did not see professionals. He saw little leadership in the congregations of South America that reminded him of the Church in Utah. Of course, he was impressed with the people and their faith, but it was a matter of demographics. They were not going to be able to build a functioning and active Church made up of wards and stakes with what he saw.

He was concerned about the gender makeup of the congregations. That image he had during his first visit stayed with him throughout his four years in South America: “So I had born upon my soul at that time the great urgency of getting men into the Church, and all during the four years of time in South America that was my one theme, to baptize men and families, and to start with the men.”[12]

From the time Elder Tuttle arrived until his last missionary conference he talked on this theme. In a meeting in Londrina, Brazil, a month after he arrived, he emphasized the need to baptize mature men “so the strength of the priesthood is in each branch.” A year and a half later in a missionary meeting in Argentina, he stated, “Remember, it is the little things that count. You don’t take one great leap to perfections. Go to men and start tracting in the business district. Ask where the boss is—sitting, sipping máte?” In February 1962, Elder Tuttle described to the First Presidency the attitude of two of the missionaries: “Two of our missionaries have taken the easy course of teaching little old women, where they get no arguments . . . but where not nearly as much good is done nor a challenge met as when they are teaching intelligent men.” He suggested what he felt was the challenge, “As I see it, Brethren, we will not be able to build chapels down here with only the Relief Society.”

The need to baptize more men was advice he always gave; however, during his last year he decided to implement it as a program. He made it a rule throughout all of the South American missions; missionaries were to teach only complete families in which the husband was present. Children or teenagers were not to be baptized unless the missionaries had made repeated attempts to teach the family, without success, or if the baptism was adding to a family that already had members of the Church. The branch president, not the missionaries, was to give the final permission as to whether any child or youth could be baptized. Elder Tuttle was pleased with the change that happened while in South America, but when he left in 1965 there was still concern the missionaries were taking the easy road while teaching. The level of priesthood and social status of the Church had to continue to change.[13]

Elder Tuttle wanted to significantly decrease the missionary influence and make the Church a member-led organization. He stated to the First Presidency, “I see that the Church cannot grow as long as it is the hands of the missionaries, regardless of how well they do their work. It must be put in the hands of local leaders: that they may be trained to bear the load and the responsibilities.”[14] For Elder Tuttle the implementation of this change was difficult, but not impossible. By the time Elder Tuttle arrived in 1961, President Thomas Fyans of the Uruguayan Mission had already developed and put into practice two plans in the Uruguayan Mission to do exactly what Elder Tuttle wanted—the six steps to stakehood and the channel 5 programs. President Bangerter in Brazil had a similar plan to accomplish the same thing. It was a matter of expanding those plans to other missions. On May 8, 1962, Elder Tuttle’s note to himself was, “Make up ‘Steps’ (to Stakehood) for every Mission. Outline (action) in writing for all to achieve. Carry this about in English and Spanish.” He spent months in training sessions explaining the programs. There were differing levels of successful implementation in the different missions, but the effect of merely talking about the program was noticeable. All the missions were soon working toward replacing missionaries with local members.[15]

Brazil South Branch presidency training, Curitiba, Brazil.

Elder Tuttle was assertive with the mission presidents concerning the goal to get locals into leadership positions. Often he was told there was no one available who could be the leader. Yet he believed potential leaders just needed to be given a chance: “One of the great thrills has been to see these young brethren, young in the Church, rising to a responsibility which they must carry and doing it in such an admirable way.” It may not have been done exactly the way he wanted, “but I found them eager and willing to learn, to attend meetings, and to receive their instructions, and then in turn give this information to others less trained than themselves.”[16]

Elder Tuttle recognized that finding leaders was a long-term goal and that they had just begun with the first steps. With the increase of converts to the Church that process was both helped and occasionally hindered. New members had the potential to fill Church positions, but many did not understand the organization of the Church. There was constant need for training and development.

Elder Tuttle immediately pushed for leadership development. When he arrived, the American missionaries were in most priesthood leadership positions in the branches and districts. They worked with Church manuals and handbooks written in English. Elder Tuttle felt he had to get these important training tools into the hands of local leaders. Part of that was accomplished in the first mission presidents’ conference held during his second trip to South America in March 1961. In two difficult and time-consuming sessions, the missions began translating and publishing the manuals and handbooks. That established the first of many important activities meant to develop the Church in South America, complete with stakes and temples.

To attract qualified leaders in South America, there needed to be a change in the general image of the Church. The Church was hampered by societal perceptions created during the nineteenth century because of polygamy. Many, especially in small towns, were aware of the missionaries because they stood out but had limited understanding of what they were actually doing in their town. Missionaries were often talked to out of pure curiosity. In some ways this was positive and in other cases a liability.

The most detrimental factor in attracting the type of people Elder Tuttle wanted in the Church was that the Church did not have chapels. The congregations were meeting in houses, converted into chapels, in which the missionaries were often living. He was sure that with the construction of sophisticated chapels the image of the Church would change—and it did. It was a time of celebration when a beautiful, newly constructed chapel was inaugurated. Proud members and missionaries could now bring their friends and investigators to an impressive building, occasionally in smaller cities, second only in size and quality to the Catholic cathedral. Elder Tuttle observed, “I think it raised the general level of the kind of people who were attracted to the Church somewhat. It made it easier to bring middle class people to attend services in a building rather than a rented dilapidated hole, which most of them were. I think it helped to achieve the goal of bringing families of some greater leadership capacity into the Church.”[17] It also helped the self-esteem of members, who now had comfortable classrooms, recreation halls, and a place to hold activities.

A concerted effort of public relations activities also assisted in a change of image for the Church. There were missionary events, often music and sports presentations, to get the name of the Church into the news. These activities may have not resulted in increased baptisms, but they did get the name of the Church into the news and into the homes of nonmembers who would generally not have been attracted to the Church. During Elder Tuttle’s last year of his mission he organized the Servicio de información sudamericano, a Church news bureau that effectively got positive stories into the media about the Church. All these programs had one purpose: to inform people about the Church.

During his four years in South America, Elder Tuttle hosted several visits of General Authorities. These visits were important public relations events and also eventful happenings for the members. The General Authorities who came were generally from the Quorum of the Twelve, including two visits from President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency. These were times of celebration for the members and missionaries. Activities accompanying these visits included numerous meetings with districts and branch organizations in each mission. There were missionary meetings in which most of the elders and sisters were able to interview with a General Authority. These were times of counsel and prophecy. These were times to meet with presidents of countries, governors of states, and mayors of cities. There were always news conferences and media events. These events were so important that members often traveled long distances to attend them. There were always cultural programs, leadership training, and personal experiences with the leaders. Not only did the members come to hear counsel, they came to visit and be with others of similar persuasion; these were festive times.

Right to left: President Paulsen, President Hugh B. and Zina Brown, Elder Tuttle, and Sarah Paulsen in Pôrto Alegre, Brazil.

Right to left: President Paulsen, President Hugh B. and Zina Brown, Elder Tuttle, and Sarah Paulsen in Pôrto Alegre, Brazil.

For Elder Tuttle, these were important times of conversation and learning. To spend time with President Brown was an exhilarating and learning experience. Elder Tuttle always included time for gospel doctrine discussion and explanation of programs and progress of every area they visited. He made sure the visiting General Authorities understood how the Church was growing and expanding. In a letter to President McKay concerning the 1963 visit of President Brown, Elder Tuttle stated, “For me, personally, this has been the most single greatest experience of my life, to have such a concentrated period of instruction from such a wise and gifted teacher. I have supposed that in each of the meetings he was talking to me personally. I have thrilled with his keen insight into the needs of the people and the wise counsel that he has given.”[18]

Concerns

Elder Tuttle enjoyed being in South America, but there were significant challenges. Financially, it was hard on the family. He had to sell his Pleasant Grove home for about five thousand dollars under its worth. Taking care of a family of seven children was not easy on a limited salary. Financing his son on a mission was possible, in part, because of the sale of fruit from some land still owned in Pleasant Grove.[19] Then on July 30, 1963, he received word from Elder Boyd K. Packer that the loan company where he had put his savings for a new home when he returned had declared bankruptcy. This comment in his diary described his frustration: “I was counting on this so much when we returned to Utah to start us out in a home and any of the other dozen things we must have. Only a miracle can in anyway rescue the savings. . . . It surely is a bitter blow to receive at this time and under these conditions.”[20]

There were other issues. In the beginning Elder Tuttle was affected by what he felt was the influence of the devil in South America. In a missionary meeting in Arequipa, Peru, in December 1961, he told the missionaries, “I have seen the spirit of the Holy Ghost and the spirit of the devil at work. We are the hands and voice of the Lord—His servants. We must not fail.”[21] There was little question in his mind where the devil was manifesting himself the greatest. The first place was the Catholic Church, primarily for the role it had taken in the evolution of Latin America.

Of equal concern to Elder Tuttle was the spread of communism throughout South America. To a group of missionaries in Argentina he discussed its expansion in the region: “It does not matter where the core of evil is. They [the communists] will always have their oar in the sea of righteousness. What does this have to do with the missionary? Everything, You have the only remedy to solve the problems of the world.”[22] Elder Tuttle believed the work he and the missionaries were doing was the only thing that would save South America from the destructive influence of the Catholic Church, which had created the region’s problems, and from communism, which threatened to take over. In a 1962 talk to members in American Fork, after describing the political problems the missionaries faced from communism and other political threats, Elder Tuttle stated, “We do not worry for the safety of the missionaries and Saints, or for myself. . . . I think that the blessings of the Lord can hold in abeyance the evil designs of men so that His work can go forward.”[23] The mission presidents’ meeting in November 1961 was important symbolically because of Elder Tuttle’s prayer to lift the veil of darkness that the missionaries felt over the region. President Palmer of the Chilean Mission described that event: “Those of us who were present on that historic occasion . . . will remember Elder Tuttle’s prayer in which he commanded the powers of darkness that seem to overcome the whole continent to disperse. From that moment forward the missionary work really took off.”[24]

Mission Presidents

Elder Tuttle recognized he was not on the front lines of the Lord’s work. The week and a half he spent as the mission president in Peru and the few days he spent in Uruguay as the mission president gave him a taste of something he wished he was experiencing. He was aware that his role in the Church was to be a coordinator, giving assistance to the mission presidents. That is what President Moyle told him to do. Elder Tuttle felt that the real work occurred in the offices of the mission presidents and on the streets by the missionaries. Elder Tuttle enjoyed his visits with the missionaries. He occasionally went out with them during an afternoon to maintain the feeling of missionary work. Elder Tuttle made a special effort to interview every missionary in all of the missions at least once a year: “At one time I knew most of them, when there were about seven hundred. Then as the number increased it got up to twelve hundred, but I no longer could call them all by name but I used to could, because I interviewed them.”[25] He also made special visits to the missionaries, and they appreciated his influence.

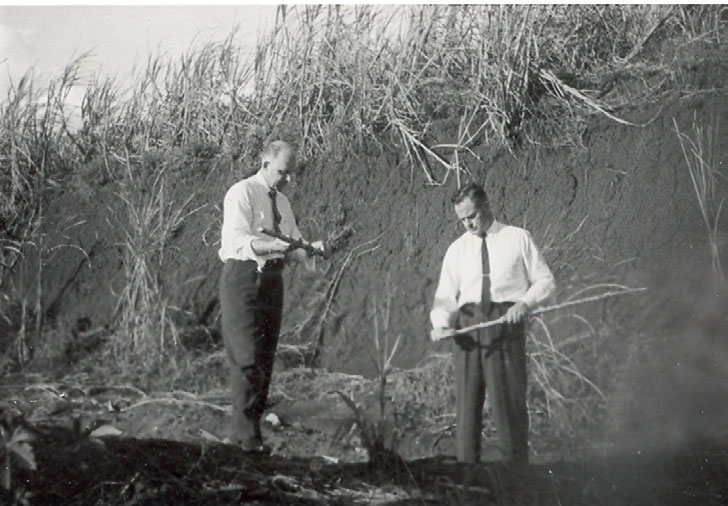

Tuttle and Bangerter in São Paulo sugarcane field.

His influence on missionaries was significant, but the real impact he had was with the mission presidents. They were his primary contacts throughout his four years in South America. He had almost weekly contact with most through phone calls, letters, mission tours, and mission president conferences at least every six months: “My association with the mission presidents is one of the choicest of my experiences. The men down there at this time were great men, everyone of them, powerful men, who have since of course been called to other important positions of responsibility. But they were powerful men, and my role was more or less to understand and share their tremendous capacities with one another.”[26]

Sister Tuttle stated, “Countless times Ted would express his thankfulness for and confidence in each of the mission presidents and their wives, as he appreciated (and envied) their being on the front lines, facing challenges and responsibilities and teaching opportunities to the hundreds of young men and women in their charge. It seems that each couple there brought particular gifts and abilities unique to the needs of their area.”[27]

There was a particular closeness between the seven presidents who participated in the rededication of South America in Machu Picchu in 1962. These presidents, with the exception of the Sharps, were all young and spent time together as a group. When the presidents were together at the conferences, a bond of strength was developed and ideas were exchanged because “with this sort of open approach, there was a good ambient among the presidents in a spirit of total cooperation among all of them. And with these great men tremendous progress was made in both the proselyting and the leadership work.”[28]

When Elder Tuttle left South America in August of 1965, he wrote a letter to the mission presidents in which he mentioned the importance of that relationship to him: “Although we shall have the opportunity of association in the future, I cannot think that it will ever be sweeter than the association which we have experienced here in the mission field. No doubt the Lord gives us a special dispensation that we might grow closer to one another in the bonds of true brotherhood while we serve in the mission field.”[29]

Results

Looking at this period, it is obvious that Elder Tuttle and the mission presidents in these seven missions put the Church on what might be called a launching pad to future growth. It was after Elder Tuttle returned to the United States that the incorporated changes began to affect the growth and development of the Church. No stakes were organized during those four years, but within two years there were stakes in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. When he arrived in 1961, there were five missions; Elder Tuttle organized two more. Missionaries were in six countries, and he introduced missionaries into Bolivia. Within a year missionaries were sent to Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela, thus placing the Church in all of the Spanish—and Portuguese—speaking countries of South America. The numbers may not appear significant looking back after forty years, but at the time it was momentous. Changes made by Elder Tuttle made possible the growth and development in the future.

In March 1961, at the time of the first South American Mission conference, there were just over 20,000 baptized members of the Church in South America. When Elder Tuttle left, that number had increased to 57,760, almost tripling the Church membership.[30] Forty-five percent of the new converts were male. Prior to his coming almost all of the units of the Church were led by missionaries, the exceptions being a few branches primarily in the capital cities. When he left, almost all missionaries had been taken out of these positions, except in recently opened areas. In the districts the same thing happened. In 1961 the districts and the missions were closely linked as missionaries handled leadership responsibility. When Elder Tuttle left, the mission organization had been separated away from district organization, and the two were functioning separately in all missions.

During Elder Tuttle’s four years of service, nineteen chapels were dedicated. There had been only three large chapels finished (two in Uruguay and one in Argentina) when he arrived. There were forty-three chapels under construction, to be finished after he left. There were 230 labor missionaries working with thirty-eight American construction supervisors. Three full-time Church schools were operating in Chile with 339 students and twelve teachers.[31]

More important than the statistical growth was the change in attitude that Elder Tuttle engendered between the missionaries and the members. This can best be shown in an experience he had within a few months of his arrival to live in South America. He was attending a small branch conference in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The branch had been open for several years and was showing prospects for further development. It would, in fact, be one of the cities where a chapel would shortly be constructed. But at this time it was still a small struggling branch, meeting in a rented house. As he stood to speak using President Bangerter as a translator, he felt inspired to prophesy. The members recalled this event for many years and used it as a beacon for their faith. Elder Tuttle said, “I was thinking as I sat here tonight that where there is just one branch in Belo Horizonte, that many of you here will see a stake in this beautiful city. When they come here to organize it, I want you to remember that it depends on the faithfulness, willingness, and ability of the members to serve.”[32] In 1981 General Authorities did return to that city, where they organized a stake. The older members in the audience remembered well Elder Tuttle’s words.

It was a change in vision that Elder Tuttle and the other mission presidents inspired in the Church. There was little talk of stakes and wards before this time. There was less talk of temples. But what they encouraged was a belief in the potential of the Church in South America and belief in each individual member’s capacity. South America was not just an outpost of the Church; it was part of Zion and could become equal to any place in the Church. In a letter to the missionaries Elder Tuttle wrote as he was leaving, he stated: “We labor in choice missions. This is the land of Zion, as you all know. These missions have been and are being richly blessed by the Lord. It is in these lands where much work must be consummated before the second coming of the Master. He is blessing the people among whom you labor, and prospering us in our efforts.”[33]

The Tuttles.

The Tuttles.

That change in attitude is shown in a comment he made in his calendar notebook. During Elder Tuttle’s first visit to general conference in April 1962, he gave an important discourse on the Church in Latin America. That same evening he recorded his thoughts in his book: “Oh, how I yearn for the day that in these meetings the Brethren report such names as Santos, Ayala, Guerra, Guzman, etc.” He looked forward to the day when the members of the Church in South America would fill positions of general Church leadership. He was to see that day before his death.[34]

When Sister Tuttle was asked what she felt was the most important legacy of Elder Tuttle in South America, she stated, “The love that people had for him extended far beyond what I had anticipated, . . . the beautiful experiences they would recall of having associated with him in circumstances that I’d had no clue about, giving blessings and just his outgoing love for people.”[35] Many members in South America, now in their aging years, have poignant memories of Elder Tuttle. Iris Spannus from Argentina recently recalled that “he was probably the kindest person I have ever known. To him everyone was the same. There were not good or bad people.”[36] Ema Silva Volger in a meeting in Salto, Uruguay, recalls being called out of an audience to visit with Elder Tuttle. Not knowing what to expect, she was surprised when he told her he had found a young man in Argentina that might be someone her sister could marry. Ema was surprised he was so interested in a member that he would do this type of thing.[37]

Death

After leaving Montevideo in 1965, Elder Tuttle was never far from South America. Though his assignments took him to other parts of the world, a part of him stayed in South America. In the mid-1970s he returned to serve as the Area Supervisor for eastern South America and lived in Quito, Ecuador. During this time, he pushed forward the work among the indigenous population with greater success than had been possible earlier in South America. After twenty months he returned to the United States, wanting to remain in Ecuador, not satisfied with what he had been able to accomplish. In 1984 he was called as the first Area President for the South America South Area, which included Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Chile. He was pleased this time to have counselors to help him supervise the work, Elders Spencer H. Osborne and Jacob de Jager. His executive secretary was A. Delbert Palmer, who had been the first mission president in Chile. During this time in Buenos Aires, Elder Tuttle was already ill and came home for medical tests. He and Sister Tuttle remained in Utah for a month taking these tests. The doctors determined he had an infected spot on his intestine due to the accumulation of bacteria over many years. After the tests were concluded, they packed their bags, said good-bye to their children, and headed to the airport, planning to return to Argentina. Before arriving at the airport they decided to stop one last time to talk to their doctor. Elder Tuttle posed the question, “If you were in my situation, what would you do?” His doctor’s reply was that he should not go back to South America because of the seriousness of his illness. Sister Tuttle stated, “Then we turned around and headed for home, with tears flowing down our cheeks all the way.”[38]

The next year Elder Tuttle spent working while trying to recuperate. He continued to undergo medical tests while he worked on several assignments, including working with the Sunday School general board. Then in the spring of 1986 doctors discovered cancer near his pancreas. The prescribed treatments of chemotherapy and radiation were effective in shrinking the cancer, but because of scar tissue, the reduced tumor pulled away from the pancreas, creating a bleeding wound that could not be cauterized. An operation was not possible. The wound would alternatively heal and then bleed. From that time to his death, Elder Tuttle received numerous blood transfusions. Soon the bleeding increased to the point that the transfusions were not sufficient.

When it became obvious to Elder Tuttle that death was imminent, he told his wife, “I just feel like I’m on a track where there’s just no getting off. I’ve just got to follow this track right on through.” Sister Tuttle was not so sure; she felt something could be done: “I’ll get him home and surely there’s something we can do. You know, you just don’t give up.”[39]

As the 1986 October general conference approached, he was seriously ill but wanted to talk. He received the assignment to speak in the last session on Sunday. Saturday evening he received a blood transfusion and a visit by his close friend and neighbor, Elder Boyd K. Packer. As he got up to speak, his weakened physical appearance was noted by the audience. There had not been an official announcement concerning his illness, and most were surprised. The effect of the disease was evident in his delivery at first, but as he talked he seemed to gain energy. His conference topic was about the need to develop faith, and he told of his mission call, in which his family’s faith was important: “We’re not going to survive in this world, temporally or spiritually, without increased faith in the Lord—and I don’t mean a positive mental attitude—I mean downright solid faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.” He ended his talk with a powerful expression of his testimony: “I bear you my humble witness that I know that God lives. I know that he lives, that he is our Father, that he loves us. I bear witness that Jesus is the Christ, our Savior and our Redeemer. I understand better what that means now.”[40]

Elder Tuttle was followed by President Gordon B. Hinckley, who told the audience of his illness, suggesting that Elder Tuttle needed the faith of the members: “It will be appreciated if those who have listened to him across the Church would plead with our Father in Heaven, in the kind of faith which he has described, in his behalf.” President Ezra Taft Benson ended the conference by endorsing President Hinckley’s suggestion and appealing to the membership for fasting and prayers on behalf of Elder Tuttle. It was a moving experience for all in attendance, particularly Elder Tuttle.

The result of those suggestions was a flood of messages and letters to the Tuttles, expressing their love for him and faith in his recovery. Elder Tuttle was moved by these expressions of love. One pleasant surprise was that many of the letters came from friends and acquaintances from South America. As his illness progressed and he felt he would not recover, he became concerned about the faith and prayers on his behalf. Elder Packer described his unusual request regarding these blessings during a visit prior to his passing:

That day Brother Tuttle spoke tenderly of the humble people of Latin America. They who have so little had greatly blessed his life.

He insisted that he did not deserve more blessings, nor did he need them. Others needed them more. And then he told me this: “I talked to the Lord about those prayers for my recovery. I asked if the blessings were mine to do with as I pleased. If that could be so, I told the Lord that I wanted him to take them back from me and give them to those who needed them more.” . . .

Can you not believe that the Lord may have favored the pleadings of this saintly man above our own appeal for his recovery?

We do not know all things, but is it wrong to suppose that our prayers were not in vain at all? Who among us would dare to say that humble folk here and there across the continent of South America will not receive unexpected blessings passed on to them from this man who was without guile?[41]

Elder Tuttle and Elder Boyd K. Packer in Brazil.

His last few weeks were spent in conversation with his wife, children, and friends. As Thanksgiving approached, he did not want to pass away on that holiday. On Friday morning November 28, 1986, after having talked to all his children, including his daughter Clarie, who was in Alaska, he quietly passed away. He was sixty-seven years old and had served as a General Authority for twenty-seven years. In his funeral he was described by President Benson as “a man of peace and gentleness, . . . one whom the Lord loves and has magnified.”[42]

Conclusion

Elder A. Theodore Tuttle lived a full and satisfying life in service to the Church. He served his country valiantly in a difficult situation during the Battle of Iwo Jima. He became a teacher and worked with the youth of the Church. He was an administrator of the Church education program where he worked to improve the quality of teaching. After his call to the First Council of the Seventy, his assignments included administrative and training responsibilities. He was a favorite speaker in the Church because of his ability to tell stories that taught the principles of the gospel. He and Marné also served as president and matron of the Provo Temple, which had profound effects on his life. He influenced the members of the Church greatly through his talks but was also an important influence to many through private and personal conversations. He and Marné raised a family of seven, who were all shaped by parents of great faith and love.

It is appropriate that during Elder Tuttle’s last few weeks his thoughts were focused on South America. The four years he and his family lived in Uruguay left a remarkable impression on the members in South America. The numerous visits before and after this period added to his love and concern for the Church in this area. Perhaps during these last few weeks, he reviewed some of his experiences in the countries of South America that he so loved. He probably pictured in his mind the majesty of the Andes, whose beauty and grandeur so impressed him. He would have thought of the beautiful city of Rio de Janeiro, where the combination of the city, the mountains, the tropical forests, and the ocean is stunning. He probably remembered his many visits to Buenos Aires with its beautiful buildings, parks, and streets. He definitely would have remembered the Carrasco area of the city of Montevideo, where his family had lived and that he loved so dearly.

More than likely during those last few days of his life, Elder Tuttle’s thoughts returned to the experiences he had with other mission presidents and their wives on June 28, 1962, at the ruins of Machu Picchu. There, under the strong influence of the Spirit, these few faithful members of the Church contemplated and prophesied about the future of the Church in South America. He would have remembered visits with members of the Church who had joined in the early years and had been faithful to the gospel during times of persecution and challenges. He would have relived interviews and meetings when he saw faithful men and women being trained and subsequently accept leadership responsibilities in branches and districts. Probably the most memorable experiences he recalled would have been the baptisms of converts who accepted the message of the missionaries and committed to the principles of the gospel. Among those baptisms were indigenous South American members who he believed were fulfilling the promises of the Book of Mormon.

In his first speech as a General Authority, Elder Tuttle wondered aloud about why he had been called: “I must confess that at the present time I do not know why the Lord has called me to this position.”[43] He surely had no inclination that most of his time would be spent in South America. Elder Tuttle’s legacy in South America is important, the effect he had on the lives of members is probably his greatest influence. His presence was symbolic of a change in the focus of the Church in Latin America. He was the first General Authority to spend a significant amount of time in the area. For the first time in its history, the leaders of the Church recognized the potential for growth in South America. Others came after him and were important in the expansion of the Church, but Elder Tuttle was the first to provide an example of direction the Church could take.

The result has been significant. When Elder Tuttle arrived in 1961, there were 45,578 members in South America, with the Church established in six countries. Forty years later the membership in South America had grown to over 30 percent of the worldwide Church. The role of the South American members continues to be important in the evolution of the Church. Such is the story of a smalltown boy the Lord loved, the son of a sheepherder from Manti.

Notes

[1] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” May 1, 1962.

[2] This image was provided by Quinn Gardner, president of the Uruguay Montevideo Mission. President Gardner was a missionary in the Uruguayan Mission, who lived mostly on the Mormon block. He had returned as a mission president and was living in the Tuttle home. In Elder Tuttle’s diary he writes of his love of animals. After going to a horse show in Uruguay and seeing the Arabian horses, he stated, “When I see things like this that I would love to own and ride I try to remember the promise that the Lord made that we could have these in abundance in the hereafter if we were faithful now” (A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar diary, August 20, 1963; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession).

[3] A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar diary, September 11, 1962, and September 4, 1962.

[4] Marné Tuttle, diary, August 11, 1961.

[5] Marné Tuttle, Tuttle Family History, April 15, 1962.

[6] Marné Tuttle, diary, October 17, 1962.

[7] A. Theodore Tuttle to Hugh B. Brown, October 12, 1963; A. Theodore Tuttle to Hugh B. Brown, January 9, 1964; copies in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[8] Family Night Notes, February 25, 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[9] Marné Tuttle to parents, July 15, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[10] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Gary L. Shumway and Gordon Irving, 1972, 1977, 208, The James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[11] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 3.

[12] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 4.

[13] El Chasqui, April–May 1965, 4. This is the publication sent to missionaries of the Andean Mission.

[14] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, February 19, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[15] A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar diary, May 5, 1962; Marné Tuttle, diary, May 21, 1962; “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” July 20, 1962.

[16] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, February 19, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[17] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 9.

[18] A. Theodore Tuttle to President David O. McKay, July 25, 1963; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[19] E. Dale LeBaron, “A Faith Promoting Experience with Elders A. Theodore Tuttle and Boyd K. Packer,” n.d.; copy in author’s possession.

[20] A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar diary, August 19, 1961; A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar diary, July 30, 1963.

[21] Marné Tuttle, Tuttle Family History, December 1, 1961.

[22] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, June 5, 1962; Marné Tuttle, notebook, January 31, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[23] Marné Tuttle, notebook, September 30, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[24] Packet for South American mission presidents’ reunion, June 23–26, 1999; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[25] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 10.

[26] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 11.

[27] Marné Tuttle, oral interview, Mark L. Grover, 2000; transcript in author's possession

[28] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 11.

[29] A. Theodore and Marné Whitaker Tuttle to South American mission president, July 13, 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[30] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[31] The statistics on the number of buildings come from a report, H. Dyke Walton, “Building Activity in South America: 1 July 1965”; copy in author’s possession.

[32] Marné Tuttle, notebook, 1961. The notes were taken in shorthand and transcribed by Marné Tuttle in 2001 and placed in her compilation, Marné Tuttle, Tuttle Family History; copy in author’s possession.

[33] A. Theodore Tuttle to the missionaries of the South American Mission, July 15, 1965; MS 4932, Church History Library.

[34] A. Theodore Tuttle, calendar notebook, April 9, 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[35] Marné Tuttle, oral interview, 46.

[36] Iris Spannus, oral interview; interview by Mark L. Grover, May 31, 2001, Buenos Aires; copy in author’s possession.

[37] César and Ema Silva Volger, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, May 21, 2001, Salto, Uruguay; copy in author’s possession.

[38] Summary of activities of Elder A. Theodore Tuttle, compiled and written by Marné in 1998, 3; copy in author’s possession.

[39] Marné Tuttle, oral interview.

[40] A. Theodore Tuttle, in Conference Report, October 1986, 93.

[41] Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, April 1987, 25–26.

[42] “Elder A. Theodore Tuttle Eulogized,” Ensign, February 1987, 74.

[43] A. Theodore Tuttle, in Conference Report, April 1958, 120.