Preparing to Serve

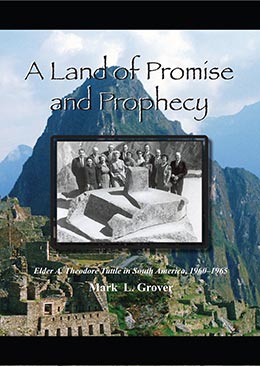

Mark L. Grover, "Preparing to Serve," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 53–80.

Two weeks on a luxury liner in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean allows a lot of time to think—more time than Elder Tuttle wanted because he was away from his family. To pass the time, he spent part of the mornings studying Spanish. He enjoyed sessions of reading the scriptures and being taught the gospel by President Joseph Fielding Smith. It was a rewarding experience to listen to the President of the Twelve Apostles discuss the scriptures and answer all questions that came to mind. During this time he thought of his mother, who had so much respect for President Smith that whenever he came to stake conference in Manti, she would say, “Now we will hear the true gospel.” Her respect was passed on to her son. These two weeks in October 1959 allowed Elder Tuttle a privilege few would ever have, to travel with and learn from a leader and scholar so admired in the Church.[1]

On this cruise Elder Tuttle read the scriptures with the express purpose of focusing on the promises to the Lamanites. The Book of Mormon promised that their descendants would continue to inhabit the Americas but that the Gentiles, or those not of the direct lineage of the house of Israel, would be inspired to immigrate to the Americas. As the Book of Mormon prophesied, the effect of this immigration upon the indigenous population would be terrible: “and they were scattered before the Gentiles and were smitten” (1 Nephi 13:14). The result, however, would not be complete destruction of the native population: “Thou seest that the Lord God will not suffer that the Gentiles will utterly destroy the mixture of thy seed, which are among thy brethren. Neither will he suffer that the Gentiles shall destroy the seed of thy brethren” (1 Nephi 13:30–31). Destroy, no, but cause significant suffering, yes. In the final stages it would be the gospel coming through the Gentiles that would help the indigenous inhabitants: “Then shall the fulness of the gospel of the Messiah come unto the Gentiles, and from the Gentiles unto the remnant of our seed—and at that day shall the remnant of our seed know that they are of the house of Israel, and that they are the covenant people of the Lord; and then shall they know and come to the knowledge of their forefathers” (1 Nephi 15:13–14).

Nephi explains how the Lord will fulfill those promises: “I will afflict thy seed by the hand of the Gentiles; nevertheless, I will soften the hearts of the Gentiles, that they shall be like unto a father to them; wherefore, the Gentiles shall be blessed and numbered among the house of Israel” (2 Nephi 10:18). This idea is expanded in the Doctrine and Covenants: “But before the great day of the Lord shall come, Jacob shall flourish in the wilderness, and the Lamanites shall blossom as the rose” (D&C 49:24). These promises gave Elder Tuttle great hope.

Unfortunately, despite all he was learning, the cruise was not particularly relaxing. First, he had never been one to sit and read for long periods of time; he needed action and things to do. And second, he wondered what he might be doing in the future. He was frustrated because he could not discuss his feelings with his wife, Marné. He wished she were there to enjoy the luxuries on the cruise and to talk with him. Despite the challenges, he agreed with her diary entry written two months earlier: “Our life together has been one long honeymoon, plus lots of hard work and many surprises. Our blessings have been a hundredfold. Our cup of happiness is brimming full. How can we contain these many blessings, let alone be worthy of them?”[2]

Concerned about the Future

Elder Tuttle was still concerned about presiding over the missions in South America and his lack of experience in the Church. As a young General Authority, he had not had many leadership experiences. Being a Seventy meant that he had few ecclesiastical opportunities for leadership. He had never served in a bishopric or stake presidency. He had been a missionary but never served as a mission president. He considered his greatest talent to be teaching, and most of his Church experiences had been in front of young students and other teachers. True, he had worked as a supervisor for several years in the seminaries and institutes and had gained administrative experience, but was that enough for what may lie ahead in South America?

He believed his training as a Seventy for the past two years had not been sufficient preparation to preside in South America. After he was called as a General Authority, he was given little instruction on how to function. He knew little of what was expected. His learning came from observation. For example, on dress etiquette he said, “I guess it’s been very seldom that I have ever not worn a white shirt in the Church Office Building, and I don’t think anybody told me I was supposed to.”[3] It was the same way he learned his job. He went with many Apostles to conferences where stake reorganizations occurred. These were times of counsel and teaching. He watched and learned from these men whom he greatly admired. He did not learn from a manual or a seminar; he observed.

But his responsibility as a Seventy was still not clear in his mind. He was not sure exactly what he was supposed to do. In the beginning, his main work consisted of attending stake conferences on the weekends, which he liked. He said, “The weekly conference assignments are a genuine joy. The saints so wonderful—it is an humbling experience to see their dedication and devotion.”[4] His work also consisted of going to the office, where he met with a few Church committees and visited with many who came to the Church offices for advice, primarily on marital problems. That type of activity, however, did not fit his personality well and frustrated him. Consequently, the first two years as a General Authority left him struggling to determine exactly what he should be doing, feeling unsettled about the role of the First Council of Seventy in general: “I think we were kind of off to one side. We didn’t know much. Nobody asked us anything, for recommendations or anything else.”[5] He wanted to make changes in the Church but did not know how to do so: “There must be some way found, however, to alleviate so many meetings and so much duplication of work in the Church. Would like a chance to work on that someday.”[6] What he probably did not realize was that the frustration he was experiencing was a period of learning and training that would be put to good use in the future. It was also a time of evolution for the Seventy. Within a short time, administrative changes would be made in the Church that would give the Seventy more direction and directly involve them in missionary work.

Part of the challenge was his busyness in activities not directly related to his position. He was asked to continue to work part time as a seminary and institute supervisor. Consequently, his work did not seem much different from before he was called; there was just more to do. He still traveled and made visits to the seminaries. In his spare time, what little there was, he was encouraged to work on his dissertation so he could finish his doctorate from the University of Utah. He got close to finishing, but his assignment to South America ensured he would always be an EBD, “Everything But Dissertation.”

The frustrations and pressures he was feeling continued to increase until he found himself hoping for a change. He was not happy being an administrator who spent most of his time in the office. He was a teacher and wanted to be in the classroom. He wrote in his diary two months before leaving for South America, “The mundane proves hard. Very discouraging—can’t seem to get even or ahead. No time to work at it either. But I shouldn’t complain! Always pressures, pressures, pressures—deadlines—appointments—schedules—meetings—hard!”[7] Shortly he was given a change in assignment that would put him in an environment he enjoyed and wanted.

Called to Serve in the Missionary Department

The change began with a phone call on March 24, 1960, from President Henry D. Moyle, Second Counselor in the First Presidency. He asked Elder Tuttle to leave the Department of Education and join him as a member of the Missionary Committee under President Moyle’s direction. It was not an easy change to make: “I accepted the assignment with mixed emotions. It means the end of a fourteen-year association with the seminaries and institutes that has been extremely enjoyable and rewarding.” At the same time it was an interesting challenge. He was excited to work with President Moyle, whom he admired for his aggressive and forward-looking approach to missionary work. He was also pleased to work with Gordon B. Hinckley, an Assistant to the Twelve, who was essentially the director of the Missionary Department and had worked in the department almost twenty-five years. He became an assistant to Elder Hinckley, helping him when he was there and taking over when he was gone. He spent a lot of time talking to mission presidents who called with questions and problems, reporting that it was “quite a change and adjustment.”[8]

He had enjoyed and appreciated the assignment, but he felt he had the job for much too brief a time. He worked with two General Authorities who were dynamic and progressive in their thoughts and attitudes. New ideas were often batted around and those General Authorities considered many suggestions. There were many challenges, and they had to be creative in their solutions. That assignment lasted for a short few months, an intensive learning period.

Elder Tuttle was participating in new and exciting developments in missionary work that would change the Church significantly in the twentieth century. Although many leaders contributed to these changes, those primarily responsible were Presidents David O. McKay and Henry D. Moyle. Missionary work had always been an important foundation of the Church since Samuel Smith, brother of the Prophet Joseph, left on his mission in 1829. The great nineteenth-century missionary activities of the Apostles to the United States, Canada, and Europe had great success and resulted in significant growth in the membership of the Church. Because the Church needed to strengthen its center, the work of the missionary was not just limited to baptizing and organizing units of the Church. Those who joined were expected to leave their homes and gather to Zion, whether in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, or Utah. The concept of the gathering was a spiritual commandment that strengthened the Church spiritually but had important ramifications socially and economically. Newly arrived converts provided strength and support for the Church in Nauvoo, Illinois. The new converts helped to colonize the West. For most, the decision to gather was a commandment they gladly obeyed because it brought them together with many who had similar ideas and beliefs.[9]

One ramification of Utah’s becoming a state in 1896 was an increase in the number of converts moving to Utah. During this time, restrictions imposed by the U.S. government limited the number of immigrants coming to Utah. Consequently, there was a period of time that converts questioned what they should do. Most wanted to come to Utah but obeyed Church leaders. A complicating factor was that the Church did not have the resources to build up the Church abroad. The concept of one Zion, in which all gathered, had resulted in strong communities of members living in the United States that were strong both spiritually and economically. The change to multiple gatherings to the stakes of Zion located in all parts of the world took time and effort before it was successful. Congregations had to be built up, and chapels needed to be constructed. It was not an easy process. The concept that the Church would grow worldwide would take time to reach fruition.

President McKay’s Influence

A major event related to that change came with the 1906 call of a young schoolteacher and administrator, David O. McKay, into the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. At age thirty-two, he brought vigor and youth to the Quorum, which offset his lack of experience in Church administration. Because of his work in teaching and educational administration, he was assigned to be with Church education, particularly in the Sunday School. He also worked with the missionary program because of his experience as a missionary in Scotland.[10]

In 1920 Heber J. Grant, President of the Church, gave Elder McKay an important yet difficult assignment to travel across the world and visit the international regions where the Church was established. His traveling companion was Hugh J. Cannon, editor of the Improvement Era. The purpose of the trip was to examine the Church in the remote areas of the world and to motivate and strengthen members, leaders, and missionaries. His trips took him to the Orient, where after visiting in Japan and Korea, he went to China and dedicated the land for the preaching of the gospel. He spent considerable time in the South Pacific visiting many of the Polynesian islands where the Church had been established. He continued going east, visiting India and finally going to the Middle East and Palestine. He returned to Utah in May 1922 with stories of adventure and descriptions of faith and dedication of the members worldwide. Shortly after his return he received another call to serve as president of the European Mission, headquartered in Liverpool, England; he was in Europe for two years.

Elder McKay’s experiences on the world tour and his time in Europe were crucial in the development of ideas on the world Church, he later emphasized as prophet. He acquired a strong belief in the role of missionary work in the Church and felt it should not only be done by missionaries but by all the members. He shared his famous phrase, “Every member a missionary,” with both missionaries and members throughout his worldwide trip.[11] His belief in local members filling leadership positions in the branches was expressed often during his mission presidency. His recommendation that the Church first start building chapels and then temples throughout the world was part of his report to the First Presidency on his mission in Europe. Returning to Utah in 1924, Elder McKay had a unique understanding and appreciation of Mormonism as a potentially worldwide church that was not necessarily held by other members of the presiding quorums. His activities for the rest of his life were related to his desire to push these ideas.

On April 9, 1951, he became the ninth President of the Church. Shortly afterward, he suggested to the Church a theme that would be important during his presidency: Zion was less a physical place and more a condition of the heart. President McKay’s son Lawrence said he “preached that Zion was not so much a matter of geography as it was a matter of principle and feeling, that the Spirit of God is within you. He preached that people should stay where they are.”[12] Even though immigration to Utah had been discouraged for more than fifty years, the concept of local Zions had never been as clearly articulated as it was by President McKay. This philosophical change created numerous other changes in Church programs. If the Church was to be built up worldwide, there had to be increased growth. It was not long until his famous challenge “Every member a missionary” was made to all the Church. His teaching during his first few years as prophet was a call to action for members in all parts of their lives, but particularly in the area of missionary work. His experiences during forty-five years as an Apostle had prepared him with knowledge and ability. As one biographer stated, “So when the mantle descended on him, it is apparent that David O. McKay knew precisely what his presidential role would be and how he would go about playing it.”[13] The first major event of his presidency was a second world tour similar to the one taken in the 1920s, in which he visited most areas of the world where there were members.

The seventy-eight-year-old prophet began his journey in May 1952 by going to Europe, spending fifty-one days visiting members and missionaries. In Glasgow, Scotland, where he served as a missionary, he dedicated a newly constructed chapel. At this meeting he told the members that the Church was not just in Utah, but international, and he placed increased emphasis on proselyting and the building up the Church throughout the world. In December of the same year, he left for South Africa and South and Central America. His visits to South America impressed him with the potential for growth: “I came to South America with a feeling there would be plenty of opposition to the Church. I go away feeling that all the people need is a better understanding of the Church and its teachings. These are great countries.”[14] He also left with a healthy respect for the local leadership of the Church.

The final leg of the worldwide tour occurred in January 1955 and took him to the Pacific islands. There he was impressed with how the faithfulness and dedication of the members had resulted in significant growth in the Church. At a special missionary meeting held in conjunction with the April 1955 general conference, he gave the following charge to the members of the Church: “Upon you and a million others who are members of the Church, rest the responsibility of declaring unto the world the divine sonship of the Lord.”[15]

President McKay not only presented the challenge but led the way in encouraging increased involvement in missionary work. Elder Tuttle explained his influence aptly: “President McKay was a great man and always of course had the bearing and looks of a prophet, the way we would envision a prophet to look and to be. And not only that, but he was far ahead of the general thinking of the Church with respect to changes and modifications.”[16] For these changes to occur, the Church needed leaders with the ability and vision to make the shifts in policy happen. One important administrator able to do so was President Moyle.

President Moyle’s Vision

President Moyle loved to work. In fact, President McKay said of him, “President Moyle [was] an abominable worker, one who saw work beyond that assigned him, and labored with equal zeal in completion of the extra labor as he did to his assigned task.”[17] That trait, learned as a child growing up in Salt Lake City, served him well as a missionary in the Swiss German Mission from 1909–11 and as a lawyer in Salt Lake City. He was actively involved in community affairs, serving on many committees and even teaching part-time at the University of Utah Law School. He served as chairman of the Utah Democratic Party and ran for governor in 1940, but lost. His Church service was significant, serving as a stake president, and as part of the first committee of the Church formed to deal with issues of Church welfare. His faith and experience led to a call to the Quorum of the Twelve in 1947 and an appointment to be part of the First Presidency in 1959.[18]

President Moyle approached every assignment with enthusiastic energy and vision. He worked hard on welfare assignments and the church building program. But it was with missionary work that he found his love. In 1954, administrative responsibility for all missionary work was given to a new General Authority missionary committee, chaired by President Joseph Fielding Smith, with President Moyle as a member. Accepting the vision of President McKay as their guiding principle, the committee suggested several changes and introduced new programs that would improve missionary work. They made proposals to increase the time missionaries had to actually proselyte, such as changing the mode of travel from boat to air and establishing a missionary training center with specialized language training.[19] They suggested a systematic plan for teaching the gospel, which the committee developed and officially implemented in 1961. The committee envisioned better training of mission presidents and a centralized translation of missionary materials. A reorganization of missionary support in Salt Lake City occurred; it was a time of innovation, change, and development. President Moyle was motivated, in part, by his experience as a young man on a mission in Europe, during which time he had limited success. He confided to his brother James the feelings about his mission experience: “There was very little conversion done, but it was building up something for the future.” For President Moyle, that future had arrived.[20]

At first the focus of increased missionary work was in Europe, but there was significant interest in what was happening in Latin America. Only two General Authorities had visited South America as General Authorities before 1956, Elder Stephen L. Richards in 1948 and President McKay in 1953. President Moyle was assigned to tour the missions of Latin America during the summer of 1956, and he and his wife spent three and a half months visiting all the areas where missionaries were working. Leaving the United States on April 26, 1956, they went to Brazil by boat. President Moyle studied Spanish during the entire voyage. It was during the first missionary meeting in Rio de Janeiro that he felt a strong impression about missionary work: “I don’t know when I was impressed more by the spirit than in my mission to [South America]. Had a very specific purpose to usher in as it were a new dispensation in missionary work on this continent. It was a wonderfully satisfactory experience for which I am very grateful.”[21]

The excitement he felt over the potential for missionary work continued as he toured the other missions. He found evidence to support his feelings on issues being discussed in the missionary committee in Salt Lake City. He saw the positive effects of a missionary studying the language before arriving and felt that with such training, a missionary could immediately begin teaching. In Argentina he saw the negative effects on proselyting when missionaries were too involved in branch and district administration: “They (the missionaries) tried to carry on the Church program in detail. It cannot be done in the small branches. It takes the missionaries away from their proselyting. The local people are not strong enough to lead out.”[22] President Moyle also saw the result of less than committed missionaries. Arriving early in the morning in Maldonaldo, Uruguay, he woke up the missionaries. The next day in Durazno, Uruguay, he gave all the missionaries a strong scolding: “I felt to get after the elders, ten in number, pretty severely. They were frivolous, light-minded and lazy. . . . I believe we helped them for the moment anyway.”[23] He became more convinced that better supervision and training of missionaries would greatly increase their commitment.

It was a time of spiritual experiences for President Moyle. He gave blessings and counsel to members of the Church. He visited Peru and Chile, which had just been opened to missionary work and felt impressed to predict success: “We predicted a growth of the Church here and the establishment of a Chilean mission soon and success to the elders called to labor here now and in the future. There was a fine spirit present. I am sure the Lord approved.”[24] During the visit, the wife of President Frank D. Perry of the Uruguayan Mission passed away. President Moyle was deeply moved and saddened by her death.

President Moyle returned to the United States with a more positive view of Latin America. He saw the potential for growth and development was more promising than first expected. South America had been seen as an outpost of the Church, which was growing slowly and had little potential for change. However, President Moyle returned with a vision of expansion. His report to the First Presidency included those feelings as well as numerous recommendations for how that growth could occur, such as improved training and better supervision of missionaries. He suggested replacing missionaries with local leaders in Church organizations so the missionaries could proselyte more. President Moyle also recommended language training prior to missionaries’ arrival and better lesson plans to teach potential converts.[25] When he was made Second Counselor in the First Presidency in 1959, he earnestly began to institute those changes. Elder Tuttle was to be part of those plans; his first assignment was to tour South America.

Elder Tuttle’s tour of South and Central America was both fascinating and difficult. He was away from his family during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. He missed his family. His first letter to Marné strongly expressed those feelings: “It is lonely on board without you. There is nothing to do but relax and eat and sleep and read. . . . Should never take a cruise alone. It just isn’t meant to be that way.”[26] A this time, they had six children and the seventh on the way. She could not leave the children for that long of a time. But Elder Tuttle did drop hints to her that they might be returning together as a family: “Please pray for me. I’m going to need more help and understanding than I have ever needed before. I’ll explain in detail when I return.”[27] He even suggested that she begin sorting through the drawers in her house.[28]

Brazil

On October 23, 1959, President and Sister Smith and Elder Tuttle arrived at the beautiful city of Rio de Janeiro and were met by William Grant Bangerter. He and his wife Geraldine (Gery) Bangerter had been in the Brazilian Mission since 1958. President Bangerter was a young, dynamic leader born and raised in the Salt Lake Valley. He had served a mission to Brazil in the early 1940s and had been a companion with James E. Faust, later a member of the First Presidency. After President Bangerter went home to the States he graduated from the University of Utah in history and worked in construction. While serving as bishop of a ward in Salt Lake City, his wife, Mildred, passed away, leaving him with young children to raise. About a year later he met an attractive, energetic nurse who was on her way to Columbia University to work on a master’s degree in nursing. The attraction was immediate, and within a few weeks Gery decided not to go east but to marry President Bangerter. He was soon called into the stake presidency of the Granite Stake and was serving in this position when he received a call from Elder N. Eldon Tanner of the First Presidency asking him to return to Brazil.[29]

President Bangerter’s skill as an administrator was apparent. President Bangerter had introduced several new programs to expand missionary work throughout the country. He ingrained in his missionaries a strong commitment to maintain the Spirit in their teaching, and the results were impressive. The mission was growing rapidly under the direction of this able and talented administrator. Elder Tuttle was impressed with the Bangerters, and a lifelong friendship soon developed.

The tour of Brazil took them all over the country, including a trip to the newly inaugurated capital city of Brasilia. They traveled northeast to the city of Recife, an area recently opened for missionary work. The first member of the Church in that area, Milton Soares, had been baptized a few months earlier, and there were a few other converts. Milton’s wife, Irene, vividly remembers the visit of President Smith and Elder Tuttle: “When he left the plane and came close to me I looked into the eyes of President Joseph Fielding Smith. At that moment I felt in my heart that truly the Church was true. He was a man of God. It was then that I felt it. From the time I shook the hand of President Joseph Fielding Smith, my testimony has grown.”[30] A member meeting was held with a large group of invited investigators in attendance. Local television news coverage had recently begun in the area, and the station was looking for stories of local interest, so reporters were also in attendance. After the meeting, the visitors gathered in the Soares home to watch the late evening news. They were not disappointed; description of the conference was the lead story.

Elder and Sister Smith with Milton Soares.

Elder and Sister Smith with Milton Soares.

The trip through the Brazilian Mission was intense but rewarding. Elder Tuttle appreciated the chance to sit and listen: “Since I had no need to direct, because President Smith was presiding, my thoughts and attention could go to other things.” What he did notice was that the number of women far out numbered the number of men in the audiences. In many of the meetings he counted the number of men and women, writing, “So I had born upon my soul at that time the great urgency of getting men into the Church.”[31]

Elder Tuttle appreciated the sweet and inexpensive pineapples and coconuts costing ten cents each and bananas ten for a dollar. He did not, however, like the humidity of the tropical climate, writing home, “It is sticky hot. One doesn’t dry out ever.”[32]

The second visit was to the Brazilian South Mission. Brazil is larger than the continental United States, and administering a mission of this size was difficult. The mission president before President Bangerter was Asael T. Sorenson. When he left Brazil in 1958, plans were already in motion to split the mission into two. The South Mission was to be the smaller geographically, covering the three lower states, but also the stronger mission because the Church had matured there the most. The Brazilian Mission was to include the very strong state of São Paulo and everything north. The headquarters of the South Mission was in the beautiful smaller city of Curitiba. Asael T. Sorenson was called in 1959 to preside over the new mission.

President Sorenson and his wife had extensive experience in the Church. Asael Sorenson served a mission with President Bangerter before World War II and returned to California, where he married and worked in sales. In 1953 he returned to Brazil to serve as president of the Brazilian Mission and remained for five years. Returning to Brazil for an additional two years in the South Mission resulted in a total of seven years as mission president. His service to the Church in Brazil was a wonderful act of sacrifice, seldom equaled for someone that young. The Sorensons took over the mission in 1953 when it was struggling to develop. With the permission of President McKay, President Sorenson began purchasing land for chapels because of the growth and development that occurred when missionary work was emphasized. His work in the new South Mission resulted in the growth of baptisms and the development of local leaders. He was only with the Tuttles for a short time, but his counsel and experience proved invaluable.[33]

Elder Tuttle was more comfortable in this mission, in part, due to a cooler temperature. He again noticed the beauty of the region: “I just walked around the mission home here in Curitiba, saw carnations in bloom, all the lovely roses are in bloom and the geraniums grow outside profusely. Most of the trees have flower blossoms on, and the landscape is beautiful.” They took a bus trip to the city of Porto União, which turned out to be an interesting experience when the bus got stuck in the mud and all had to get out and push, including President Smith. When it started to rain, the bus’s roof leaked, forcing Sister Smith to move from her seat and Elder Tuttle to use his raincoat inside the bus to keep dry. “Life is simple and primitive,” was his observation.[34]

Back in Pleasant Grove, Sister Tuttle was caring for six children as well as several animals. She always kept busy, often with tasks not normally anticipated from an expectant mother: “I have just come in from separating a cow from her calf. We had them both staked out, and she got loose from the chain somehow. I haven’t heard her mooing, but when she got loose and headed for the calf, I’d begun to wonder!” Her response to Elder Tuttle’s request for more letters stated, “Honey, one reason you didn’t get more letters from me is that by 7:00 p.m. I’ve about had it and can hardly wait to get horizontal!”[35]

At this juncture, Elder Tuttle became concerned with the slow pace of the tour. His hope was to be home for Christmas, but at the pace they were going that was not going to happen: “This continues to be a difficult tour for me. I think the Smiths are enjoying it, but I can’t quite get the full spirit of it. I guess I just have to have things my way. . . . I wish I could speed it up a bit—but I can’t. And I can’t leave them—but it will work out somehow.” Elder Hinckley even called Sister Tuttle to express frustration with the slow speed of the trip and said he would do what he could to speed it up. However, that was not to be, and the trip actually extended longer than expected.[36]

Argentina

The next stop was the beautiful city of Buenos Aires, and Elder Tuttle immediately saw the contrasts between Brazil and Argentina: “It is entirely different from Brazil. It is the most progressive of all of the So. American countries. Streets are wider, more beautiful, and more (in a way) like U.S.A.”[37] There to meet them at the airport were two people who would become close friends to Elder Tuttle. Leading the Argentine Mission at this time were Laird and Edna Snelgrove. The name was well known to Elder Tuttle because of the ice cream company in Salt Lake City that bore the Snelgrove name. President Snelgrove was born and raised in Salt Lake City and served in the Mexican Mission in the early thirties, staying mostly in the United States. His father opened an ice cream business. When the Great Depression started, President Snelgrove worked with him in the business before and after his mission to Mexico. He went to a couple of years of college, but his father needed help, and he was soon giving all his time to the ice cream business.[38]

Edna’s family, originally from South Carolina, had moved to Sonora, Mexico, where they raised cattle, but left Mexico in 1912 and moved to Douglas, Arizona. She served a mission in the Central States Mission and when she returned, she met and married Laird. She studied interior design at Arizona State University. After nine months of marriage, Laird was made a bishop. Five years later, he was called as a counselor in the Granite Stake presidency and also worked in civic organizations, including serving as president of the Sugar House Rotary Club. His call to Argentina came at the beginning of 1960, so he had been in the country about a year when the Smiths and Elder Tuttle arrived.[39]

The Smiths and Elder Tuttle spent more than two weeks in Argentina. They traveled from the southern region in Bahía Blanca to the hot and tropical areas in the north. The changes in weather conditions resulted in colds for all the visitors. However, the colds did not inhibit the visitors from being impressed with the people. Elder Tuttle said, “The faith and the devotion of these people is amazing. They surely are humble with their devotion to the church so many of them travel so far to get to conference meetings and under such unfavorable conditions, it is a faith-promoting experience to learn of the sacrifices they make to get to conference.”[40]

In Buenos Aires, Elder Tuttle observed the Smith’s interesting relationship. Jessie Evans Smith loved to shop, and Buenos Aires offered temptation for shopping that could not be resisted. Elder Tuttle was once assigned to go downtown shopping with her. He luckily missed her second shopping excursion. Elder Ted Lyon, the mission secretary, drove Sisters Snelgrove and Smith downtown to shop. Unable to park close to the shopping district, they got into a taxi and visited several shops on the famous Florida Street. At the first shop, Sister Smith bought alligator-lined purses and wallets and consequently spent all the money she had on hand, but she was not through. They found a store that sold silver goods, where she spent all of Elder Lyon’s and Sister Snelgrove’s money, and again she was not finished. Their final stop was at a place that sold sweaters, and she bought one for each of her eighteen grandchildren. The bill was 147 dollars, but no one had any money. Elder Lyon negotiated with the store to have the items brought to the mission home. Elder Lyon’s reaction was, “It was really fun spending all of President Smith’s and President Tuttle’s money.”

The next evening was described by Elder Lyon as “the Day of Reckoning.” The sweaters were delivered, and Sister Smith pointed to her husband when payment was requested. He happened to have 150 dollars in his pocket, which he paid with some reluctance. When Elder Lyon returned to the table, President Smith’s instructions to him were, “Elder Lyon, please do not take my wife shopping tomorrow.” Her response, “Oh, don’t listen to him. He’s the biggest pussycat there is.” She said he would appreciate having the gifts for his grandchildren. For his part in the adventure, Elder Lyon was sure he was soon to be transferred, “I guess I’m heading for Chubut,” considered to be the worst part of the mission.[41]

This incident illustrates what Elder Tuttle appreciated about the Smiths. Elder Smith had the reputation throughout the Church of being hard, stern, and disciplined. What Elder Tuttle found was that he was a kind and gentle man with a great sense of humor. Sister Smith had a flair and openness about her that complemented her husband’s public persona. She had been a performer all of her life and loved people. While the two men were interviewing missionaries, she was singing and entertaining the rest. Elder Lyon described a missionary meeting in Buenos Aires: “Sister Smith conducted the talent show. It was really fun and different. We all had to do something and a truly wonderful spirit was developed. Sis. Smith talked about her experiences with her husband.”[42]

In a letter to Sister Tuttle, Sister Smith poked fun at her husband and Elder Tuttle. Wishing Sister Tuttle was with them, Sister Smith jokingly suggested an absence of fun on the trip: “With two men along I have to stick pretty well to my knitting, because they are always thinking about missionary work, but then once-in-a-while I kinda chip in and try to get them to break down.”[43] President and Sister Smith had a playful banter that they both appreciated. They interacted well with each other and enjoyed their experiences together. President Snelgrove, after spending two weeks with them, learned the very human side of President Smith, writing, “You couldn’t ask for sweeter or kinder people than President and Sister Smith.”[44]

One incident in the northern Argentine city of Tucumán was particularly upsetting to President Smith. While leaving a taxi, he got distracted and accidentally left his portfolio, which included the scriptures he had used since his days as a missionary. All efforts to recover such prized possessions were unsuccessful. Though disappointed and distraught over the loss, he did put a positive spin on the incident: “Maybe someone will find them and make good use of them and they will bring him into the Church.”[45]

While in Argentina, Elder Tuttle received a letter from President Henry D. Moyle with interesting news. He indicated he was happy that Elder Tuttle would be coming home “with such a full and complete knowledge of all of the missions in both South America and Central America.” He then informed him of a change in policy that was to occur in the Church:

President McKay feels there has been one rather important decision made since you left. He feels that we can better supervise the work of missions than to continue the present visits of the general authorities. He has, therefore, suggested that the plan of assigning general authorities to tour the missions, particularly in the United States, be discontinued. We hope to be able to assign members of the general authorities to supervise the missionary work throughout the world much as is now being done by Brother Dyer in the European Mission. This plan should be rather completely worked out by the time of your return.[46]

This letter must have alarmed Elder Tuttle a bit. His suggestion a few days earlier to his wife was showing signs of coming true: “I cannot fully appreciate all the new and wonderful things here, because you are not with me. However, I console myself that there will be another time.”[47]

Uruguay

Next stop on the tour was Montevideo, Uruguay. Elder Tuttle was impressed with the beautiful parks: “It is quaint with statues many places and beautiful flowering jacuranda (sp) trees (the purple ones) on many of the streets. . . . There are ‘squares’ in most of the city at various spots with statuary and trees and walks and benches in them. They are very picturesque and beautiful.”[48] In Uruguay they were met by President Arthur Jensen and his wife, Geniel. They would not get to know them well, however, because they had finished their mission and were on their way home. Together on December 2, they all went to the dock, where they met President J. Thomas Fyans, his wife, Helen, and their daughters as they disembarked from a boat to take over the Uruguayan Mission. President Fyans had been raised in Idaho and Salt Lake City. He graduated from West High School in Salt Lake City and worked at Safeway, a grocery store, and eventually ZCMI, the department store owned by the Church. He went on a mission in 1940 and served in the Spanish American Mission. After his mission, he married Helen and worked into a management position with ZCMI. With significant management experience, he would develop unique programs for proselyting and administration in the Uruguayan Mission. He became an important confidant to Elder Tuttle and a close friend.[49]

The series of conferences and missionary interviews continued. One interesting visit occurred in the interior of Uruguay at a small place called Isla Patrulla. This was a very small village close to the city of Treinta y Tres, which had attracted a large number of members and investigators. Getting there posed a problem. The roads were bad, and the trip by car would be difficult for President and Sister Jensen, so they decided to fly. When they arrived at the Treinta y Tres airport, they were dismayed to see a nice new plane under repair and an old red plane as the only possible transportation to fly them to Isla Patrulla. They decided that the Smiths and Jensens would fly to the conference while the others drove. When the door flew open just after loading the plane, the pilot promptly pulled and wired it shut. Furthermore, they experienced difficulty getting airborne. Elder Tuttle describes what happened:

The plane then bounced out and over the hill and down, and back. It revved up again, and I could see that they were not going to make it. Again over the hill they went and the sound of the motor faded away. We could hear nothing but a drone. Pretty soon the plane came putting up to where we were. Out came Art (Arthur Jensen). President Smith had cut himself on the head and was bleeding. He got out. The pilot said he could make it by going clear to the end of the runway. I said, ‘Why not let Tom and me ride out?’ President Smith exclaimed, “Nobody is going in this———plane!” Then I said, “Damn plane!” President Smith said, ‘Thank you!’[50]

They decided to take two cabs to the conference. Along the way they saw some ostriches, and Sister Smith decided she wanted an ostrich egg. After spending an hour looking for a nest without success, they made their way to the chapel, an hour and forty-five minutes late. The missionaries in charge of arrangements had started the meeting and were holding a testimony meeting until the guests arrived. The chapel was then dedicated by President Smith.[51]

Meanwhile, back in Pleasant Grove, Sister Tuttle continued to keep busy: “One day I chased an errant pig and caught him in the ditch at the west end of the property. The only way I could get him home (pigs do not herd) was to catch him by his two back legs and “wheelbarrow” him home.”[52]

Chile and Peru

The next stop was Chile where they spent a couple of days with missionaries from the Andes Mission and then flew to the mission headquarters in Lima, Peru. Here Elder Tuttle considered it an honor to finally become acquainted with President James Vernon Sharp. President Sharp was from Utah and had served two years in the Mexican Mission when, in 1926, he asked to extend his mission and go to South America to replace Elders Rey Pratt of the First Quorum of the Seventy and Melvin J. Ballard. At the time, Elder Pratt had been serving as mission president of the Mexican Mission, but spent most of his time touring South America with Elder Ballard in order to open up mission work. President Sharp finished his mission by traveling through Bolivia and Peru, preaching on his way home. Upon returning to the United States and getting married to Fawn Hansen, he graduated from the University of Utah in electrical engineering and owned and operated the Sharp Electric Company with his brother. He held several callings in the Church, including serving as one of the first branch presidents of the Mexican branch in Salt Lake City and as a counselor in the Olympus Stake presidency. He went to South America with his wife as the first president of the newly organized Andes Mission, which included Peru and Chile. During the year Elder Tuttle spent with them in South America, a great friendship developed.[53]

Peru proved to be an emotional and somewhat difficult experience for Elder Tuttle. He had long held interest in those whom he considered Lamanites and had yet to encounter many on his trip. But Peru was the center of one of the greatest indigenous civilizations, the Incas. The majesty of their empire was but a memory after four hundred years of subjugation. His emotions could not be contained when he observed the maid’s two-year-old daughter in the mission home: “I weep when I think that she is born into such a world as this one—especially down here. She will never have a chance to know anything but misery and superstition and fear and heartache. She will be underprivileged, underfed, undernourished, and downtrodden all her life. . . . I can hear her crying now. She is not allowed in the mission home so she is standing outside the door crying.”[54]

This feeling of concern combined with great love remained with Elder Tuttle his entire life, and he exerted all he could to help bring the gospel to this people, which he believed was the only solution to their plight. Peru always held a special place in his heart.

In Peru he developed negative feelings about the Catholic Church. He believed it was a major reason for poverty there. One experience was noteworthy: “We visited a Catholic church today where the people stop in to pray, it is filled with gold and priceless things, and the coffers clink with money. I stood and listened to the coins drop in the boxes for half an hour. It is an abominable thing.”[55]

Elder Tuttle expected to spend Christmas in Peru, but an emergency changed his plans. President Victor C. Hancock, president of the Central American Mission, came down with a serious case of pneumonia and was put into the hospital. Elder Tuttle received notice from the First Presidency that he was to go to Guatemala City as soon as possible. After he left, the Smiths stayed in Peru, where they continued to hold meetings and interview missionaries. During their stay, Sister Smith fell and broke her arm.[56]

In early January the Smiths arrived in Guatemala, and Elder Tuttle’s tour resumed. The Smiths and Elder Tuttle returned to Utah on January 10, very happy to be home. It was an important and historic trip. Elder Tuttle was now to wait for his assignment to serve in South America.

Notes

[1] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Gary L. Shumway and Gordon Irving, 1972–77, transcript, 132, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[2] Marné Tuttle, diary, August 14, 1958; in Marné Tuttle’s possession. Marné kept annual diaries during this period. They are listed by date and not page number. All materials are used with her permission.

[3] Tuttle, oral interview, 136.

[4] A. Theodore Tuttle, missionary diary, March 17, 1960; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[5] Tuttle, oral interview, 144.

[6] Tuttle, missionary diary, March 17, 1960.

[7] Tuttle, missionary diary, August 15, 1960.

[8] Tuttle, missionary diary, March 24, 1960.

[9] For a discussion of the immigration, see Fred E. Woods, Gathering to Nauvoo (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2002) and Eugene E. Campbell, Establishing Zion: The Mormon Church in the American West, 1847–69 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1988).

[10] The general biographical information on President McKay for this study was taken from Gregory A. Prince and William Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005). A less academic history is found in Francis Gibbons, David O. McKay: Apostle to the World: Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986).

[11] McKay to Rudger Clawson, February 5, 1923, in Gibbons, David O. McKay: Apostle to the World: Prophet of God, 126.

[12] As quoted in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 366.

[13] Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 281–82.

[14] As quoted in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 294, 338.

[15] As quoted in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 351.

[16] Tuttle, oral interview, 157–8.

[17] As quoted in “Impressive Final Rites: Thousands Honor President Moyle,” Deseret News, September 21, 1963, A1–A2.

[18] Biographical information is found in Richard D. Poll, Working the Divine Miracle: The Life of Apostle Henry D. Moyle, ed. Stan Larsen (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999).

[19] The Language Training Mission was eventually established in Provo in 1964 with Spanish being the first language taught. See a history of the mission in Richard O. Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel in His Own Language: A History of the Provo Missionary Training Center and Its Predecessors, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: Missionary Training Center, 2001).

[20] As quoted in James D. Moyle, Remembrances (Ogden, UT: Weber State College Press, 1982), 64.

[21] Henry Dinwoodey, journal, May 10, 1956, Church History Library.

[22] Dinwoodey, journal, May 17, 1956.

[23] Dinwoodey, journal, June 6–7, 1956.

[24] Dinwoodey, journal, July 5, 1956.

[25] Poll, Working the Divine Miracle, 159.

[26] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, October 17, 1960; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[27] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, October 24, 1960; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession. Elder Tuttle realized he would probably be coming back to South America when, during the trip, he heard part of a telephone conversion between President Smith and someone in Salt Lake City, “that I shouldn’t have been in on, but I couldn’t escape it. So I knew from that there was to be a different kind of organization in the missions and that I would be involved” (Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1977, transcript, 16, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library).

[28] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November 8, 1960; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[29] William Grant Bangerter, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, April 26, 2001, Alpine, Utah; copy in author’s possession.

[30] Irene Bandeira Soares, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, 1994, Recife, Pernambuco, transcript, 3–4; copy in L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[31] Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 4.

[32] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, October 24, 1960; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[33] Asael T. Sorensen, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1973, transcript, 1, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[34] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November 11 and 12, 1960.

[35] Marné Tuttle to A. Theodore Tuttle, November 7, 1960.

[36] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November 13, 1960.

[37] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November 13, 1960.

[38] President Snelgrove returned to college in his later years, graduating at ninety-one years old from Brigham Young University in 2003.

[39] Laird C. Snelgrove and Edna H. Snelgrove, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1987–88, transcript, 1, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[40] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November, 21, 1960.

[41] Thomas Edgar Lyon, mission diary, November 16–17, 1960; copy in Thomas Edgar Lyon’s possession.

[42] Lyon, mission diary, November 24, 1960.

[43] Jessie Evans Smith to Marné Tuttle, October 31, 1960; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[44] Snelgrove and Snelgrove, oral interview, 90.

[45] Snelgrove and Snelgrove, oral interview, 89.

[46] Henry D. Moyle to A. Theodore Tuttle, November 15, 1960; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession. Elder Alvin R. Dyer, an Assistant to the Twelve Apostles, was living in Europe at the time where he supervised all the European missions.

[47] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, November 8, 1960.

[48] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, December 4, 1960.

[49] J. Thomas Fyans, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, St. George, Utah, November 27, 2000.

[50] This is found in a one page description by Tuttle entitled, “Greatest Entourage in the History of Mission Tours”; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[51] Clark V. Johnson, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, Provo, Utah, March 29, 2001; copy in Mark L. Grover’s possession.

[52] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 117.

[53] James Vernon Sharp, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, Salt Lake City, 1972, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[54] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, December 16, 1960.

[55] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, December 16, 1960.

[56] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 29.