Peru: Fulfilling the Prophecies

Mark L. Grover, "Peru: Fulfilling the Prophecies," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 232–60.

J. Vernon Sharp and his wife, Fawn, had a few restless nights after they received a call from President Henry D. Moyle. They had been asked to go to the west coast of South America and open a new mission that would encompass both Chile and Peru.[1] For Vernon it was a chance to return to South America, where he had been one of the first missionaries and a pioneer for the Church. Fawn was pleased to finally go to a place she had heard so much about but never visited. It would be three years of growth and joy, but it would also have its share of struggles.

President Sharp finally had the opportunity to finish what he had started as a missionary in South America. In 1928, at the end of his mission, he had been asked by his mission president Reinhold Stoof to work toward fulfilling a prophecy that had been on the minds of leaders since the Church was organized: to proclaim the gospel to the indigenous people. In 1928, when Elders Melvin J. Ballard and Rey L. Pratt returned to the United States after their six-month mission, they returned home by visiting northern Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru. Elder Ballard felt something special in the Argentine city of Jujuy, which is close to the Bolivian border, in part because it was a city inhabited primarily by the indigenous population. After the visit, Elder Ballard believed it was time to take the gospel to the descendants of Lehi who had received so many promises in the Book of Mormon. Sharp was asked to go to Jujuy with two other elders to fulfill Elder Ballard’s desire.

The trip did not turn out as had been expected. First, there had been a long period of rain, and the roads and railway into the city were closed. The missionaries entered Jujuy on a horse-drawn cart used to collect garbage. Second, there was a shortage of housing, and it took some time to find a place to live. Finally, the opposition to their presence by both the Catholic Church and an evangelical Protestant group was fierce. As a result, the missionaries had little success in finding anyone to teach. Opposition to the missionaries became so malicious that they received physical threats, oranges were thrown at them, and finally a yearlong rental agreement for their rooms was broken and they were expelled from their apartment. They had no place to live, and none of the merchants would sell them food. They were literally forced out of the town. Sharp returned home to Utah, traveling through Bolivia and Peru, while the other missionaries returned to Buenos Aires.

But what Sharp learned in this experience would be important in his time as mission president. He saw things among the indigenous population that were disturbing; those that were in northern Argentina lived under a difficult situation only slightly above slavery. He realized that attempts to teach them were difficult because of their social condition. He came to believe that in Argentina in 1928 the time had not arrived to bring the gospel to the indigenous peoples. Further north in Bolivia and Peru, however, conditions were not as oppressive. His recommendation to the First Presidency was that if missionary work were to go to the indigenous population of South America it should start in Peru. When he returned to Peru in 1959, it had been thirty years since he had made that recommendation. It would be his privilege to be one of the first mission presidents to serve in a primarily Lamanite nation. His role as a pioneer for the Church in Latin America was to continue.[2]

A Brief History

Though most experts on the archaeology of the Book of Mormon believe that the immediate descendants of Father Lehi lived in Mesoamerica, President Sharp was not completely convinced. One visit to the city of Cuzco and the ruins of Machu Picchu in Peru persuaded him that the greatness of the Inca empire suggested a civilization of significant skill and advancement. The Book of Mormon people may not have first arrived in South America, but surely their influence was important in the creation of one of the greatest civilizations of the world. The great cultures of China, Mesopotamia, India, and Egypt were built in fertile, highly productive valleys with great rivers. Part of their greatness came from their ability to use life-giving water in highly productive lands. The Incas, however, stayed away from the rich valleys and built a civilization on the tops of mountains with land that appeared, at first glance, unable to result in economic prosperity. Their civilization was centered in the city of Cuzco, 11,400 feet high and above the tree line.[3]

Their achievement is even more astonishing considering the additional challenges they faced. Communication was maintained through a system of high mountain roads that emanated out of Cuzco. Highly trained runners traveled these roads, some of which were carved out of solid rock while others were built on suspension bridges spanning deep canyons. They spread throughout a kingdom beginning in the north in the present country of Ecuador and ending in the south in present-day northern Argentina. The Incas had few domesticated animals, the most important being the llama and the alpaca, which were used as pack animals, though neither was very adept at this activity. The concept of the circle was not important in their world, and the Incas never developed the wheel, yet they were able to build sophisticated bridges and irrigation systems over rough terrain. They did not have a knowledge of iron but were skilled metallurgists in using copper and tin to make bronze. More impressive, they were able to cut large stones weighing several tons, move them over long distances, and build large, mortarless walls so close together that a piece of paper cannot fit between the stones. For hundreds of years, these walls have resisted many powerful earthquakes common in the area.

Their political system was equally impressive. The ruler was called the Inca and politically controlled a large geographic region. Their communities were organized to increase agricultural production most effectively. They stored a proportion of all their food to feed the population in times of famine. They had no concept of personal property and all worked for the good of the community. They had a highly sophisticated religious system with a belief in the return of a white God, though it was not as prevalent as with the Aztecs in Mexico. The beautiful settlement of Machu Picchu, built before the coming of the Spanish, became a symbol of the greatness of the Inca empire. It was never found by the Spanish but was discovered in the twentieth century.[4]

The first Europeans to Peru were white but definitely did not have the positive effect on Andean society as the Incans had hoped. Led by the Spanish explorer Francisco Pizarro, a group of less than two hundred men with twenty-seven horses completely overthrew the Inca empire of more than twelve million people and took control of the entire region in little over a year. Taking advantage of dissension between the rulers and using deception and betrayal, they entered the capital city of Cuzco in November 1533, and soon the Inca empire was under Spanish control. The primary purpose of the Spanish was economic extraction and exportation of goods to Europe, primarily precious metals. The Spanish government was installed, and the city of Lima was established as the capital, primarily because it was at a port. Lima became a large, beautiful city known for its architectural beauty.

The Spanish conquest was catastrophic to the local population. The Spanish established a system of economic production that took advantage of the labor of the natives. Granting land to the conquerors included control of the native population to provide labor. The presence of workers on the land was essential, and many were moved from traditional homelands to the places of greatest value to the conquerors, primarily the mining areas, to extract precious metals for the Spanish. Disease and overworking had a devastating effect.

The religious changes were equally devastating. The close relationship between church and state in Spanish rule resulted in the attempted destruction of the native religions in favor of Catholicism. Places of native worship were destroyed, and Catholic churches were built on the ruins. Forced conversion occurred, and the physical evidences of pre-Columbian worship disappeared. The outward acceptance of Catholicism, however, hid the continuing practice of some native beliefs within the rituals of the Catholic Church.

Peru became a society split between its indigenous past and the new structures of Spanish society. The differences were often geographic with the coastal areas being European and the highlands continuing to show strong indigenous influence. This geographic influence on culture continues to the present day. On the coast the culture is largely European or a mixture of the two races, but in the mountain communities the majority of the population is indigenous and the main languages are Quechua and Aymara. This division is also economic with little of the wealth held by indigenous peoples.

As the economic center of the Spanish empire in South America, Peru was the political capital controlling most of the areas claimed by Spain. As the regions outside Peru began to develop, local political units were established, but Peru retained its importance to Spain. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Spanish control over its American colonies weakened. However, Peru maintained its relationship with Spain longer than most of the continent. It was the center of power, and the desires for independence were not as great in Peru as in other areas. In 1820, after freeing Chile, the Argentine liberator José Francisco de San Martín came up the west coast and was eventually able to gather enough support to advance on Lima, where he declared Peru’s independence on July 28, 1821. Because of political conflicts, San Martín left the country, and the northern South American liberator Simon Bolívar came to Lima and was able to secure legitimate independence in December 1824.[5]

Since independence, Peru has had a series of governments that had some democratic elements. Ruled primarily by a conservative party controlled by the elites, Peru in the twentieth century was significantly influenced by a socialist party, the APRA (Alianza Popular Revolucionario Americana), headed by Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre. In the late 1950s, when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came to Peru, the country was led by Manuel Prado y Ugarteche, a member of a powerful banking family and conservative elite. It was a period of economic struggle and inflation resulting in a military takeover in 1968 by General Juan Velasco.

The Church in Peru

Church leaders had discussed Peru long before the missionaries finally arrived in 1956. In 1851, when Elder Parley P. Pratt was on his way home from his mission in Chile, he wrote a long letter to Brigham Young describing his experience. In this letter he suggested that had he gone to Peru instead of Chile he probably would have been more successful, primarily because there was more freedom of religion. “Should Peru sustain her liberties, a field is opened in the heart of Spanish America, and in the largest, best informed and most influential city and nation of South America, for the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and the fulness of the Gospel to be introduced. . . . I had much desire to go to Peru at this time.”[6]

Elder Melvin J. Ballard liked Peru on his return home from Argentina, stating: “I have never seen a more industrious, hard-working lot of people in my life than the millions of Indians we saw in Bolivia and Peru. My heart went out to them in anxious desire, for I saw them . . . robbed of their lands and their glorious civilization, a much better civilization than was brought by Pizarro. . . . It was our privilege to call on the government officials of both Bolivia and Peru, and to explain our mission and desire to have missionaries go to those lands. . . . It is our desire that those precious promises made to their forefathers shall be fulfilled.”[7]

With the establishment of a mission in Argentina, the introduction of the Church in Peru would wait an additional thirty years. American members of the Church lived in Peru on and off for many years working in the mining business or with the United States government. During his worldwide tour in 1954, President David O. McKay visited Peru and held a meeting with the American members in the country. He returned home with a desire to open a mission. A year later, Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles made Lima a stop on his tour of South America and was impressed with the potential for growth of the Church in the country.[8]

It was not until 1956 that activities toward opening a mission got serious. One impetus was the move of Frederick G. Williams and his family to Lima to work in 1956. Williams had been a mission president in Argentina and the first mission president in Uruguay. When he arrived, Church meetings were being held in the home of a former Argentine missionary, Stanley Moore, but were soon moved to the Williams home. Before long, several Americans were attending the meetings. Brother Williams wanted missionaries in Peru and, as he did in Uruguay a few years earlier, contacted the General Authorities urging that a mission be opened in the Andes region of South America.[9]

In April 1956 he wrote a letter to the First Presidency indicating that thirty-three English-speaking members lived in Lima. He reported they were working with around fifteen Spanish-speaking nonmembers who had shown interest in the Church. He asked for assistance and guidance: “Our problem is that we have no organization. We belong to no mission. . . . Without an organization or authorization, we don’t know just what or how much to do. . . . I feel that a mission could very advantageously be established in Peru. . . . There are thousands of good people who are not satisfied with what they have and I am sure that many would join the Church if they were given an opportunity.”[10] In the letter, he requested that President Moyle visit with their group in Lima and examine the situation.

Plans were already under way to do exactly what Williams was suggesting. As a result of previous correspondence with President Frank D. Parry of the Uruguayan Mission, the First Presidency was contemplating change. On April 17, 1956, President Parry received approval to organize a branch of the Uruguayan Mission in Lima and send two missionaries to the country if permission was granted by the government. On the same day Williams received word that President Moyle would be coming to Peru, and he quickly began gathering information on how the missionaries could legally enter the country.

President Moyle arrived in Lima on July 6, 1956, and two days later organized the Lima Branch with Williams as president and Moore as his counselor. The next day President Moyle visited with the minister of justice and religion, receiving instructions on how to get the Church officially recognized in Peru. They immediately filled out a formal petition to begin the process. They were told missionaries could begin proselyting immediately. Missionaries arrived on August 3, and a home was purchased in which to hold meetings. In less than two years the Church was granted official recognition. The missionaries were successful in baptizing several investigators, and a second branch was organized in Lima in 1958 and a second home purchased by the Church to be used as a chapel. A third branch was organized in Toquepala, a mining community in southern Peru where several American Latter-day Saint families were working. The community gave them a chapel, which was dedicated by Elder Spencer W. Kimball during his visit in 1959. This was the state of the Church when the Sharps arrived.[11]

The Sharps’ Service

On July 8, 1959, President Sharp had an informal interview with President McKay. The prophet’s secretary called Sharp, who was a repairman, and said President McKay had an iron that needed to be fixed. After giving Sharp the iron, President McKay asked to sit and talk. Within a few days after President McKay’s visit, Sharp received a call from President Moyle’s secretary asking him to come to his office that afternoon, where he was officially asked to serve as the president of a mission soon to be organized. The mission was to include Peru and Chile, which had similar amounts of members. In that meeting the name was determined to be the Andes Mission, and President McKay suggested the headquarters be in Lima, though he wanted official mission offices to be established in both countries. The Sharps arrived in Lima on October 6, 1959, and met with Frederick Williams, who had been a missionary with Brother Sharp in Argentina in 1926–27.[12]

After a short trip to Uruguay and Argentina, the Sharps visited Chile on October 29, where the first of two organizational meetings was held with Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Then on November 1, they went to Lima, where a second meeting was held to organize the mission. In this meeting Elder Lee talked about Elder Ballard’s prophecy, which President Sharp had been present to hear and record. Elder Lee described how the growth of the Church in South America had followed Elder Ballard’s predictions and then made his own forecast: “In my judgment there are no missions in the world which hold so much promise as the missions of South America. The work is going to continue to grow and we have not yet seen the end of the number of missions that will be established. There are those that will see the future growth.”[13]

Sister Sharp noted in her diary that her husband had been present for the giving of two important prophecies related to the evolution of the Church in South America.[14] Before leaving Elder Lee informed the Sharps that their mission included not only Chile and Peru but also Bolivia, though no missionaries were to be sent to Bolivia at the time.

Administration of a mission in two countries was difficult. Three weeks were spent in Peru and three weeks in Chile, leaving the Sharps to feel they were not able to unpack. The most significant administrative challenge was the distance between the two countries. They also had challenges related to natural disasters. Within two months of the organization of the mission, an earthquake hit Arequipa, Peru, killing many and destroying many homes. Sharp offered the services of the missionaries to translate for government officials. Then five months later, on May 18, 1960, an earthquake hit Chile and he again was instrumental in getting supplies from the Church to the area. It was two years of hard work with an eye toward the eventual separation of the mission.[15]

At the end of 1960, President Joseph Fielding Smith, his wife Jessie Evans Smith, and Elder A. Theodore Tuttle visited. After an extensive tour of the mission, President Smith recognized the area was too large for one person to administer. Shortly after the visitors left, President Sharp received a letter from the First Presidency announcing that the mission would be divided. That division happened on October 1, 1961, in a meeting held in Lima. The Peruvian part of the mission was still called the Andes Mission because it included both Peru and Bolivia. The Chilean Mission became the sixty-fourth mission of the Church.[16] The Sharps were relieved to have the two areas separated because it took a great burden off their shoulders, and they were able to concentrate on the Church in Peru.

The Sharps were pleased with the appointment of Elder Tuttle as the president of the South American missions in 1961 and developed a close friendship with him when he visited them with President Joseph Fielding Smith. Elder Tuttle had great respect for Sharp and his role as a pioneer in South America and during his first visit in December of 1960 wrote: “Two weeks ago President Sharp was just a name. Now he is, in my opinion, a great man, a personal friend, one whom I look forward to associating with in the future.”[17] The Sharps were the oldest and most experienced of all the mission presidents in South America, being fifty-six years old. All the other mission presidents were in their late thirties and early forties with young children. The Sharps’ children were adults and all but one married by the time they left for Peru. Besides the age difference, Sharp had a historical connection to the work because of his early mission. Elder Tuttle’s respect was reciprocated by the Sharps: “It was really great to have Pres. Tuttle to coordinate our work. . . . This really proved to be a great step forward in South America.”[18]

The Indigenous Population

The one issue that concerned and interested both President Sharp and Elder Tuttle was the question of the indigenous peoples in South America. The Church began in Lima on the Pacific coast among the European population. That is where the Americans lived who formed the foundation of the first branch and where the missionary work started. Both President Sharp and Elder Tuttle, however, felt working with the indigenous population was a major responsibility of the Church in Peru. That goal was to prove more difficult than expected.

To understand Peru is to appreciate the differences between the two racial groups and cultures. The coastal region surrounding Lima was populated by Europeans and retained strong European cultural traits. The native population resided primarily in the inland mountainous areas. A significant percentage of Lima’s population was mixed racially but still had European cultural traits. Consequently, the missionaries taught and baptized the descendants of Lehi in Lima, but for Elder Tuttle and President Sharp that was not enough. They wanted to introduce missionaries into the highlands among the pure and cultural indigenous peoples. Even before coming to South America to live, Elder Tuttle had expressed his desires to the student body of Brigham Young University: “Brothers and sisters, my heart responds to the yearnings of these Lamanite people. The Lord has made promises to them. He will keep them. They deserve the gospel of Jesus Christ. They need it. I think the Lord wants you and me to carry this gospel to them.”[19]

Taking the gospel to the indigenous peoples became a major goal for both Elder Tuttle and President Sharp. This desire was so strong that it became a burden that rested upon their shoulders. “Because of his visits to Peru, Elder Tuttle became acutely aware of the way the Gentiles had inflicted suffering upon the indigenous peoples. During his visit to Peru in December of 1960, he was saddened by the control the Catholic Church had over the people.”[20]

While in Peru in October 1961, Elder and Sister Tuttle visited the tomb of Francisco Pizarro in the San Francisco Cathedral in Lima (La Cathedral). After seeing the tomb and other bones in the catacombs under the Church, Sister Tuttle exclaimed, “People were lined up to touch the wood of a cross, which is said to have healing power, at the Merced Church. I had a desire to put my arm around a little beggar and say, ‘Don’t look so sad. There’s hope yet.’”[21]

The following month the Tuttles returned to Peru for a mission tour. It was during this tour that they made their first visit to Cuzco, the ancient capital of the Incas. They also visited the ruins of Machu Picchu. It was a memorable trip beginning with the experience of flying to Cuzco in a plane that had to travel above twenty thousand feet and did not have a pressurized cabin. They had to keep an oxygen tube in their mouths to breathe. In Cuzco they felt the effect of high elevation for the first time in their lives. Sister Tuttle almost fainted as they went out to see the sights. But they enjoyed the city of Cuzco, and the ruins of Machu Picchu were impressive: “Words cannot describe the grandeur of the breathtaking scenery.” For the Tuttles, equally noteworthy were the indigenous peoples. They were “sad to see the condition of the Indians.” Two days later in a talk to missionaries, Elder Tuttle spoke for the first time about the feelings of oppression and evil that appeared to be in South America: “We pray for the Lord to hold evil in abeyance and to direct you to those who are seeking the truth. . . . I have seen the spirit of the Holy Ghost and the spirit of the Devil at work. We are the hands and voice of the Lord—His servants. We must not fail.”[22]

That feeling reached a peak by December 12, 1961, at the first mission presidents’ meeting held after the Tuttles arrived. Elder Tuttle had recently written to Elder Harold B. Lee about his feeling: “The work is going well, but the power of the adversary is continually present. It is observable on every hand. He seems to have such power in the lives of these people, both among the high and the low, that it takes continual vigilance, such prayer and faith to stabilize the Saints and missionaries and to advance the work here. At times it seems that a pale of darkness and evil hangs heavy over this land and people, and threatens to smother the light of truth so recently kindled in this dark land.”[23]

At the end of the three-day conference, a special prayer was held in which Elder Tuttle prayed that the veil of darkness be lifted from the continent. A very emotional good-bye was said as the presidents left. Mable Palmer of the Chilean Mission describes her feelings after that experience: “From that day forward, the proselyting work began to move forward at an unprecedented rate. Such power and faith made an impression on everyone present that they will never forget.”[24]

Elder Tuttle realized the inadvisability of moving too fast in Peru. After talking about how best to approach missionary work, Elder Tuttle suggested to President Sharp that he continue to concentrate missionary work in the city of Lima and coastal areas in order to build up a strong organization before expanding into the interior. After that had been done then they could cautiously move into the highlands.[25] In February 1962 Elder Tuttle reported to the First Presidency that they were not teaching the Lamanites in most of the missions. In his talk to the Church in the 1962 April general conference, he barely mentioned the Lamanites.[26]

But the fact that they were not doing more with the indigenous population continued to be a frustration. President Sharp decided to send two missionaries to Cuzco to establish the Church in the area. He and Fawn went to Cuzco on October 30, 1961, where they found property to rent for the first branch in the city. Little growth was anticipated.[27]

Probably the greatest expression of love and concern for the indigenous population occurred in the mission presidents’ conference held in Peru in June 1962. As the mission presidents and their wives explored the Inca ruins of Machu Picchu, they contemplated the greatness of the civilization that had created this impressive settlement. In their early morning testimony meeting on the mountain most talked of how the experience had affected their testimony. In this meeting Elder Tuttle summarized most of their thoughts as he talked about their responsibility to the indigenous peoples:

I feel a sense of urgency about the work, the necessity of our fulfilling the promises that have been made in the Book of Mormon, because we are the ones who should do it—when they would return again to the gospel and be restored—to their original place. I have felt great sadness, sympathy, and particular tenderness for these people because of the conditions under which they have lived. . . . When we see these people acting like beasts of burden, devoid of any hope, and realizing that we are the ones directing the missionaries to wipe this all away. It is a great responsibility that comes to us.

He then blessed the land in a prayer, calling South America, “this land of the Lamanites.” He asked that they as mission presidents have a “vision of Thy work, of what we must do and how we must organize and proceed so that we can do better what Thou hast called us to do.” Elder Tuttle expressed an urgency to begin to work more with the non-European population.[28]

During this conference President and Sister Sharp received a letter telling them that they would soon be released. Sister Tuttle explained how this news affected all present: “This was a very touching announcement for all of the mission presidents, as all realized that they must face the same thing one day.”[29] It was a difficult and emotional day for the Sharps. It had been a year since their daughter Darlene passed away, and the pressure and work of running the mission had helped to ease some of the struggles of that difficult experience. They would now return home and experience the pain over the death of their daughter that had been lessened by being so far away.

They had to leave earlier than expected when Elder Gordon B. Hinckley informed them of problems at home with their store. [30] Because of the early release of the Sharps, Elder Tuttle went to Peru and presided over the mission for two weeks. It was something that thrilled him. Since he was called into the First Council of Seventy at an early age, he did not have the chance to serve as a mission president. He had spent the past two years talking about missionary work and missionary programs, but he did not have the opportunity to actually incorporate his own ideas. Even though it was only for two weeks, it was a pleasing experience for both him and Sister Tuttle. He arrived in Peru on August 17 and immediately ascertained how the mission was functioning. His assessment was positive: “President Sharp is a great organizer and has things in fine shape. . . . President Sharp and Fawn have done a wonderful job in this mission, although there are yet many problems to solve.”[31]

The day the Sharps left, Elder Tuttle met with the supervising elders and talked to them about how to get more baptisms. Essentially he incorporated the program of President Fyans in Uruguay. “I spent the day changing things, President Sharp has laid an excellent foundation. Now we need to baptize.” On August 23 he surprised some elders early in the morning who were asleep when they should have been up. He then had a second meeting with the supervising elders where he talked about the need for a member program and importance of looking toward the organization of a stake. On August 25 he introduced President Fyans’s member/

The Nicolaysens

The time, however, was too short for Elder Tuttle. President Sterling Nicolaysen and his wife, Vivian, and their three children arrived in Lima on August 31, 1962. For the next few days President and Sister Tuttle trained the Nicolaysens. Elder Tuttle’s assessment of the Nicolaysens was positive. “He has the right phil. & spirit. At least, it is like mine, & we get along fine.”[33]

There were similarities between the two men. Nicolaysen was a school administrator and loved to teach. He had served in the army during World War II as had Elder Tuttle. His experience in the Spanish American Mission just after the war had instilled in him a conviction of the ability of local members to lead the Church. For several hours they talked about the programs that Elder Tuttle believed would work in Peru. The first was turning over the branches to the local leaders. President Sharp had held off on this activity so President Nicolaysen could do it all at once. Elder Tuttle had a list of the branches and suggestions of possible branch presidents. Within the next six weeks they reorganized ten branches installing native leaders in each unit. “So we threw ourselves right in the middle of the next phase in mission development—the capacitation of member leaders.”[34]

President Nicolaysen followed the pattern established by President Sharp and Elder Tuttle. He believed they needed to strengthen the units of the Church already functioning before opening up new areas to the Church, particularly in the highlands where most of the indigenous peoples resided. He stated, “This was all part of a sound principle which dictates that we go first where there are people with some cultural readiness to receive the Church, to be interested in the kinds of things the Church would offer socially and organizationally.”[35]

His first year was spent calling local leaders and allowing them to gain experience. During his second year, President Nicolaysen refined the local programs by including additional training. Then during his third year, he stepped up the training and sent additional missionaries into the highlands of Peru. President Nicolaysen knew that the expansion of the Church into those areas would not be easy. The indigenous population of Peru was still suffering from significant discrimination. The connection with Indian culture was a hindrance in their ability to fit into Peruvian culture. “When people come from the hills, if they leave behind the garb of the Indian—the indigenous people—they make some effort, if not to masquerade as non-Indian, at least to set aside their Indian background.” President Nicolaysen was fully aware that sending missionaries into areas where indigenous people lived was significantly different from sending missionaries into the other areas of Peru. The social and physical problems such as malnourishment and limited education, compounded with discrimination, suggested that a different approach needed to be taken in these areas.[36]

Elder Tuttle appreciated these concerns but still believed they could do more with the indigenous peoples. In February 1962 he expressed frustration to the First Presidency that after two years in South America they were still involved in only limited activities with the Lamanites.[37] During President Hugh B. Brown’s visit to Cuzco in February 1963, Elder Tuttle expressed his worry over the Church in that region. On February 7 in a Cuzco meeting with sixty-seven people, of which only twenty were members, President Brown echoed Elder Tuttle’s concern: “Although there were many men present in the meeting, there were only a few who seemed to have the ‘Mormon Look’ or seemed to be potential leaders.” Two days later, when talking to the four missionaries in the city, President Brown suggested that “opposition was clearly in evidence and the condition of the people beyond description.” The missionaries needed to continually recognize that the blood of Israel was among the people, and they needed to be searched out. President Brown believed that “Lehi, Nephi, Mormon, Moroni and others of the Prophets who were on the other side were yearning to have their descendants hear and to accept the Gospel.” He stated that some of the great men and women of the earth were in Cuzco. At the close of this meeting, the missionaries knelt with their leaders, and Elder Tuttle “invoked the blessing of the Lord upon the missionaries, Cuzco, and the people there, that the Lord would prosper the work and touch the hearts of the people concerning His message.”[38]

Sister Tuttle felt the blessing had the immediate effect “to dispel the sad gloom there and brought a ray of light and hope to these people.” President Brown felt the change too: “The President said that there was a great future in store for Cuzco and that although he had felt somewhat depressed the first two days, that he could now see great hope for the work of the Church in this city.”[39] President Brown had expressed his strong feelings toward Peru in a missionary conference held earlier in Arequipa in which he admonished the missionaries to be positive about Peru and realize the importance of serving in this part of the world. He suggested that many may have been disappointed in their call, but they should not have been. President Brown said, “I believe sincerely in my very soul that in South America you have the richest harvest ahead of any part of all the world. I could be wrong but it seems to me that the Lord is just ready to have this nation reclaimed and taken out of the grasp . . . of the devil and taken over into the hands of the Lord.”[40]

Even though Elder Tuttle already had a strong love toward Peru, his feelings were soon to increase. His son David received his mission call to the Andes Mission and was ordained an elder by President Brown during this visit. Eleven months of his mission were spent in the city of Cuzco, and his love and that of the entire Tuttle family increased for the area. David left a year early, at the age of eighteen, because he was already living in South America. A farewell was held in Uruguay on March 3, and Elder Tuttle and David left for Peru the following day, stopping in Paraguay and Bolivia. David was in Lima for a brief time and then assigned to Cuzco.

President Brown’s visit marked a significant increase in the activities toward the indigenous peoples. This change can be seen by Elder Tuttle’s augmentation of activity toward this population. In May of that year they received approval to open Church schools in Chile which Elder Tuttle suggested was “the greatest step forward for the Lamanites in this country since the Gospel was introduced.”[41] Then on May 30 he asked his assistant Donald Cazier and Elder Quinn Gardner, a missionary in the Uruguayan Mission, to visit Ecuador and Colombia on the way home from their missions for the purpose of ascertaining the feasibility of sending missionaries into those two countries. That was followed by Elder Tuttle’s visit to Ecuador in October. He liked the indigenous capital of Quito and described it as having “vigor and vitality and most of the people are Lamanites or a mixture thereof.” He felt that “nearly every section of the city could be tracted. There are many Lamanites here, and the majority are a fine looking group of people.”[42]

Unfortunately, tragedy also struck the Church in the area shortly after President Brown’s visit. Missionaries were allowed to travel on their way home, and two missionaries from the Uruguayan Mission, Elder Phillip Styler and Elder Randy Huff, visited the ruins of Machu Picchu. They became separated for a short time, and Elder Styler slipped and fell into a nearby river. For several days search parties combed the area. His body was discovered downstream from the ruins eight days later. It was a very difficult time for all involved, especially President Nicolaysen, who stayed in the area during the entire time. Elder Styler was buried in Peru, and the Tuttles periodically visited his grave.[43]

Bolivia

Ecuador was a place that interested Elder Tuttle, but his main undertaking was to get missionaries into Bolivia. Bolivia had attracted the Church for a long time. Elders Ballard and Pratt had also gone to Bolivia on their way home. President Sharp on his way home from his mission in 1928 had gone from Argentina to Bolivia, spending several days tracting and working. He was favorably impressed: “I found personally more receptiveness as I talked to them, first tracting in La Paz, Bolivia, at the time than we had ever in Argentina.”[44] Bolivia was visited several times as missionaries left Argentina and Uruguay returning to their homes in the United States.

The General Authorities in Salt Lake City were interested in Bolivia and had surprised President Sharp when he was assigned to Lima as the new president of the Andes Mission by indicating that Bolivia would be in his mission. They told him he should go to Bolivia “at our discretion as we got the work moving in the other countries, we were to proceed in Bolivia.”[45]

In January 1960 the Sharps took their first trip to Bolivia. President Sharp met with Sister Alwina Hulme, a member of the Church who had been baptized in Argentina. At the time she was working for the United Nations in La Paz, so she was able to schedule a visit for President Sharp with the minister of foreign affairs to gather information on what was required to legally enter the country. President Sharp also looked for a house in La Paz to be rented as a chapel.[46] He returned to Peru, believing the Church would shortly be established in Bolivia. But the activities of beginning a mission in Peru and Chile took up President Sharp’s time, and the next time he went to Bolivia was two years later. On February 5, 1962, they returned to La Paz with all of the papers ready to turn into the minister’s office to become legally registered in the country. The experience was a disappointment. After being sent from office to office, one lawyer finally informed them that they needed one additional paper from Salt Lake City, and it had to be the original, not a copy. “Our leaders in Salt Lake will have to decide what they want to do next.” Missionaries who were ready to go into Bolivia remained in Peru to open up new cities.[47] The privilege of sending missionaries into Bolivia was to fall to his successor, President Nicolaysen.

Elder Tuttle’s first trip to La Paz was in May 1962. He met with Sister Alwina Hulme and enjoyed the visit. He was impressed with the city: “We could easily put six missionaries there with plenty to do. It will be hard but the people are there and need the message of the work, although we will need some healthy missionaries.”[48] In March of the following year he passed through Bolivia while taking his son David to his mission in Peru. He immediately noticed the native population: “There are Lamanites all over, very similar to Cuzco which is so much like La Paz that they could be twin cities.”[49]

President Nicolaysen dedicated much time to Bolivia. During the middle of September 1962 he spent eight days in Bolivia working on the problem of registering the Church. Then on October 8, 1963, Elder Tuttle and President Nicolayson visited their lawyer in La Paz and were informed that the permission was pending. Elder Tuttle stated: “It is ripe for the Gospel. There is a great deal of interest among all those whom we visited about what we are teaching and what we believe.” Permission was finally gained in November 1964. Elder Tuttle stated to the First Presidency a few months later, “Now the branch has thirty members, who are of the leadership type people.” President Nicolaysen sent the first missionaries into Bolivia on November 24, 1964.[50]

Progress

Progress with indigenous peoples was seen in other parts of South America. A month after the Church was opened in Bolivia, missionaries were sent for the first time into the interior of Paraguay where they made contact with the Tavítera tribe. Missionaries had been in Paraguay since 1948 but had only been teaching those of European descent in the capital city of Asunción.[51] There had been discussions about moving into areas with an indigenous population, but nothing happened. During the visit of President Hugh B. Brown to Paraguay in 1963, they visited a tourist spot that included a typical Guarani indigenous village open to tourists featuring the native women in much more limited “native” apparel than expected. All were nervous until President Brown made everyone feel at ease with numerous humorous comments about the village. It was an experience that made the Tuttles and those in the group appreciate the humor and humanity of President Brown. During this visit they had serious discussions about the importance of opening the missionary work to the indigenous peoples.[52]

Elder Tuttle was finally pleased with the progress of the work. He had reached one of his goals, which was to open missionary work in Bolivia. With activity going forward in Ecuador, he believed that finally the promises to the children of the Book of Mormon would start to be fulfilled in earnest. Marné Tuttle wrote the following to President and Sister Nicolaysen: “Ted is fascinated with what he saw and the possibilities of working with the Lamanities more directly, as you know.”[53]

They were to receive visits from two different General Authorities who had great interest in the activities of the Church in relationship to the indigenous peoples. The first was Elder Tuttle’s best friend and confidant, Elder Boyd K. Packer. The official purpose of the visit was to examine the needs and possibilities of establishing an editorial center in South America for the production of Church literature. Elder Packer, however, had great interest in the indigenous populations because he had been a teacher in the first Native American seminary classes in Brigham City, Utah. He enjoyed his visit to Peru. He had been on the Church Lamanite Committee for several years, adding to his interest in the indigenous populations. Elder Tuttle had talked to him often about what he was trying to do in South America. Now it was Elder Packer’s chance to see it in person.

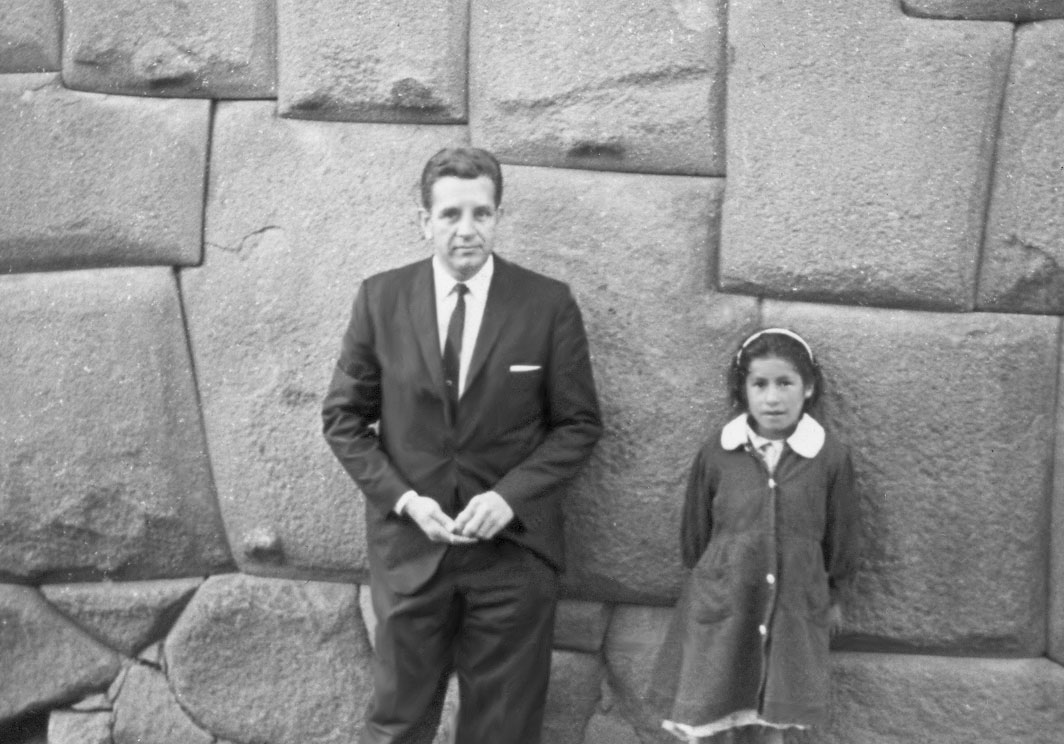

Elder Boyd K. Packer at Inca ruins.

A moving experience of the trip occurred in Peru during a sacrament meeting in Cuzco. Elder Packer noticed a six-year-old native boy who had come into the meeting. He was obviously hungry because as the meeting progressed, he slowly moved toward the sacrament table, which had the sacrament bread. Members in the congregation were embarrassed and tried to dissuade him and quietly remove him from the chapel. After a time Elder Packer motioned to the boy to come to him, which he did. Elder Packer placed the boy on his lap and then on the chair next to him that had been occupied by Elder Tuttle, who was talking. He hoped this act taught a lesson to the congregation concerning pride. Notice Elder Packer’s comment on what happened to him at that moment: “I felt that I had an entire people in my arms. . . . A voice from the dust, perhaps the dust of those small feet, already rough, whispered to me that this was a child of the covenant, of the lineage of the prophets. . . . I have been in Cuzco since that time and now I see this people whom I had held in my arms, coming to be baptized, to preach, to preside.” This trip was important to Elder Packer in expanding his interest southward to see the fulfillment of the blessings of the Book of Mormon toward indigenous populations.[54]

Activity with the indigenous people received a significant emphasis with Elder Spencer W. Kimball’s visit in June 1964. He had a specific responsibility in the Quorum of the Twelve to work with the indigenous population. Most of his attention had been with Native North Americans, but this visit introduced him to the indigenous population in South America. He preached to all of his audiences, regardless of the country, about expanding missionary work to all of the indigenous peoples. He and his wife, Camilla, even entertained district and branch leaders in Brazil with an American Indian war song. The visit to Bolivia was special for Elder Kimball. He stated that he enjoyed being in the presence of so many indigenous members more that his visit with the president of Peru. He predicted growth for the Church in Bolivia. He emphasized that both the Americas were Zion and likened the two continents to the two great wings of Zion.[55]

His trip to Peru included a visit to a town that was of particular interest. Elder Tuttle realized that the type of missionary work that was being done with the European population in South America would not work with the indigenous populations. He took Elder Kimball to the city of Huánuco in the Huallaga Valley and showed him a program that was helping the native population. A German immigrant by the name of Walter Fiedler had purchased a large plot of land and was using it to teach the indigenous people marketable skills. He had joined the Church and constructed a chapel on his property and was holding regular services. Elder Kimball was there on a Sunday and enjoyed the meetings. After Church they went to see a special workshop called “Taller Mormon.” Elder Kimball was shown a shop “where young boys are being taught how to make inexpensive benches and tables for the people here. In the back they plan to fix a sink in the kitchen to teach the women how to cook. They have a sewing machine and a knitting machine. Many of the little women brought their embroidery to show the scarves and aprons they were making. So proud.”[56]

The growth of the Church among the indigenous peoples had progressed to the point that Elder Tuttle decided to focus his April 1965 general conference talk on the Church in the Andes. He began his talk describing the lives of these peoples in the Andes, including outlining the poverty that existed. He suggested that this level of poverty did not exist during the time of the Book of Mormon. He described the grandeur of the indigenous civilizations and suggested that the problems of subjugation were the result of both governmental and religious failures to recognize the people’s worth. He indicated that only recently had the Church begun to work with the indigenous populations but that the programs of the Church offered the greatest hope for both the spiritual and physical well-being of the people. He ended by declaring that “the day of the Lamanite is at hand.” He asked for the blessings of the Lord to be with the members of the Church “to aid our brethren, the Lamanites, in their striving to reach their destiny.”[57]

Conclusion

When Elder Tuttle left South America in 1965, he was pleased that some progress had been made to introduce the gospel to the descendants of Lehi. He was able to report to the First Presidency that there was a branch of thirty members in La Paz and missionaries were in Cochabamba. Missionaries would soon be introduced into Ecuador, Venezuela, and Colombia. But he had hoped to do more. He had a strong belief that the Church’s school system in Chile would soon be expanded into Peru and Bolivia and that this would be a vehicle for improving the lives of the indigenous peoples of South America. He returned to Salt Lake City and was put on the Church Lamanite Committee under Elder Kimball’s direction. But this committee was primarily interested in the activities of the Church among the Native Americans of the United States. He often became frustrated by this focus and would regularly remind the other members of the committee that “for every Lamanite in the United States there were sixteen in South America—in Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador.” He returned to South America as a General Authority administrator and lived in Ecuador for almost two years. It was here that he was able to work seriously on the issues related to the indigenous peoples of South America. He again left South America with concern that he was not able to do enough. It was an issue that concerned him until his death in 1986.[58]

Notes

[1] Peru was part of the Uruguayan Mission until 1959. Chile was connected to the Argentine Mission.

[2] Information on the Sharps comes from J. Vernon Sharp’s journal and oral history (journal of J. Vernon Sharp, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; J. Vernon Sharp, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, December 1972, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library).

[3] For a treatment of the Incas, see Brian S. Bauer, Ancient Cuzco: Heartland of the Inca (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004).

[4] See Richard L. Burger and Lucy Salazar, eds., Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004).

[5] For a history of Peru, see Peter F. Klarén, Peru: Society and Nationhood in the Andes (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[6] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 503–4.

[7] Melvin J. Ballard, in Conference Report, October 1926, 38–39.

[8] Frederick S. Williams and Frederick G. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree (Fullerton, CA: Et Cetera Graphics, 1987), 289.

[9] For a history of the Williams family in Peru, see Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 289–301.

[10] Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 299–300.

[11] Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 295, 299.

[12] Sharp, oral interview, 43–48.

[13] Fawn Hansen Sharp, Life History of Fawn Hansen Sharp (n.p.: n.d.), October 31, 1959.

[14] Hansen, Life History, November 1, 1959.

[15] Sharp, oral interview, 52–53.

[16] Sharp, oral interview, 68; “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” October 1, 1961.

[17] A. Theodore Tuttle, mission conference talk, Lima, Peru, December 23, 1960; copy in author’s possession.

[18] Fawn Hansen Sharp, Life History, April 9, 1961.

[19] A. Theodore Tuttle, “The Power of the Gospel,” Brigham Young University Speeches of the Year, 1961 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1961), 7.

[20] A. Theodore Tuttle to Marné Tuttle, December 16, 1960; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[21] Marné Tuttle, diary, October 2, 1961.

[22] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” November 28, 1961; Marné Tuttle, diary, November 28, 1961; December 1, 1961.

[23] A. Theodore Tuttle to Harold B. Lee, November 30, 1961; copy in author’s possession.

[24] Mable Johansen Palmer, My Life’s Adventure (Lethbridge, Canada: privately printed), 108.

[25] Sharp, oral interview, 71.

[26] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, February 19, 1962; copy in author’s possession; A. Theodore Tuttle, in Conference Report, April 1962, 120–23.

[27] Sharp, Life History, November 2, 17–19, 1961; Tuttles to “Dear Friends,” March 21, 1962; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[28] Marné Tuttle, notes, 1962.

[29] Tuttle, “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” July 2, 1962.

[30] Sharp, Life History, August 21, 1962.

[31] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” August 17, 1962.

[32] Marné Tuttle, diary, August 24, 1962; “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” August 23–26, 1962.

[33] A. Theodore Tuttle, diary, September 1, 1962; “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” September 1, 1962.

[34] Sterling Nicolaysen, oral interview, interview by William G. Hartley, 1972–73, 33, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[35] Nicolaysen, oral interview, 40.

[36] Nicolaysen, oral interview, 36.

[37] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, February 19, 1962; copy in author’s possession.

[38] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” February 7, 1962.

[39] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” February 9, 1963; Marné Tuttle, diary, February 9, 1963.

[40] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” February 12, 1963. A transcript of part of the talk is in an appendix to a description of the visit of President Brown under this date. The talk, however, was given on February 5, 1963.

[41] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” May 29, 1963. Quinn Gardner, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, June 9, 2001, Montevideo, Uruguay; copy in author’s possession.

[42] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” October 1, 3, 1963.

[43] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” May 22, 1963.

[44] Sharp, oral interview, 34. For a description of the trip, see the journals of J. Vernon Sharp, Church History Library.

[45] Sharp, oral interview, 34.

[46] James Vernon Sharp, Life History of James Vernon Sharp (1988), 51–52.

[47] Sharp, Life History, February 5–6, 1962.

[48] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” May 23, 1962.

[49] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” March 6, 1963.

[50] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” October 8, 1963; Nicolaysen, oral interview, 40.

[51] Néstor Curbelo, Historia de los Santos de los Últimos Días en Paraguay: Relatos de pioneros (Buenos Aires: privately published, 2003), 17–30.

[52] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” January 18, 1963; A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency. There is no date on the letter, but it was written after June 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[53] Marné Tuttle to Sterling and Vivian Nicolaysen. There is no date on the letter, but it was written after the missionary presidents’ conference in São Paulo in March 1962; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[54] Boyd K. Packer, That All May Be Edified (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft,1982), 134–36.

[55] Marné Tuttle, diary, June 10, 1964.

[56] Marné Tuttle, diary, June 14, 1964.

[57] A. Theodore Tuttle, in Conference Report, April 1965, 29–31.

[58] First Presidency to A. Theodore Tuttle, July 29, 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession; A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972, 1977, 171.