North Argentina: Branching Outward

Mark L. Grover, "North Argentina: Branching Outward," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 261–85.

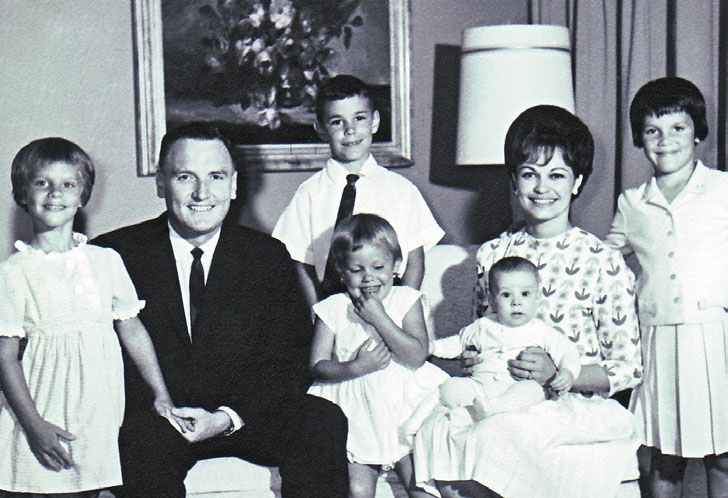

Receiving a phone call from a General Authority was not uncommon for the Stone family. O. Leslie Stone was serving as a stake president in northern California. So when his son Ronald V. Stone answered the phone and President Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency was on the line, Ron thought the call was for his father. “Are you Ronald?” President Moyle asked. “Yes, I’m Ronald.” When Ron said his father was not in his home, President Moyle responded, “No, I want to talk with you.” Ron was then informed that the Church was about to divide the Argentine Mission and that they wanted him to be president of one of the missions. In shock, Ron asked that he be allowed to discuss the call with his wife and family.

It was May of 1962, and Ron was only thirty-five. He had been home from his mission only ten years. During this time he had graduated from Brigham Young University, married Patricia Judd, and worked seven years in sales for the Skaggs-Stone Wholesale Company in Oakland, California. He and Patricia had three small children. He was confident of his managerial skills but was not sure he was ready to preside over the missionary work for half of Argentina. After discussing the call with his wife and his company managers, he called President Moyle and officially accepted the call. Thus began a three-year experience in which the Stones took over a new mission, strengthened a Church organization that was both new and weak, and expanded missionary work into regions of Argentina where the Church had never gone. It was a formidable task for a man ten years removed from his own mission.[1]

But the Lord knows those who are called and the talents they hold. Stone knew how to manage and administer, and he had a strong spiritual background that was essential in making the necessary decisions. He would focus his attention on missionary development and proselyting. He would organize training sessions to prepare local Church leaders for the eventual organization of stakes and additional missions. But his background and training outside the Church would be put to good use in only a small part of his responsibilities. His work and innovation in the area of public relations would be an example to the rest of the missions on how to get the name of the Church known in a way of value to the missionary program.

Northern Argentina was new territory for the Church. From the time the Church arrived in Buenos Aires in 1925, missionary work had centered around the capital. Missionaries had gone to the major population centers of the interior, Rosario, Córdoba, Mendoza, and surrounding cities, but not much further north. Historically, the limited number of missionaries being called to Argentina suggested that the focus of the Church should be in areas close to the center of the Church. Argentina is a large country with great distances between regional capitals. It was not until leaders began to look at the possibility of splitting the mission that missionaries were sent north into Salta, the Gran Chaco, and Resistencia.

Not only was the north a region where few had ever heard about the Church, it was also an area that staunchly maintained traditional cultural practices and beliefs. In Argentina this meant a strong Catholic presence. Priests were not pleased when other religious groups would come into the area. Latter-day Saints learned this early in 1927 when the far northern city of Jujuy was tested for missionary work, only to have the town turn against them so they could not even rent a place or purchase food. Though times had changed and opposition was not as great, the missionaries faced significant obstacles in many of the northern regions.[2]

These areas needed a public relations activity that would get the name of the Church into the public mind in a positive and productive way. President Stone had the talents to do just that. First, he was a musician and had played in and directed dance bands since he was in high school. His wife was a well-known musician in Utah and had studied at the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. President Stone had a master’s degree in speech and television from Brigham Young University and knew how to get the name of the Church into the public mind. Though this was only a small part of his responsibility, he developed a public relations program unequaled anywhere else in South America. The activities of the program reached a potential audience of more than six million people, telling much of Argentina who the missionaries and members of the Church were.

Organization of the North Argentine Mission

Argentina is a big, impressive country. In reality it is one country with two distinct parts, a city and the rest of the nation. The country covers more than one million square miles, including the humid tropical region of the north, the Andes on the east, the lush agricultural land of the central region, the grasslands of the pampas, and the desert and cold, mountainous regions of the south. The diversity of the country is mirrored in its population. The north shows the indigenous influence of the native Andean cultures, while the rest of the country is strongly dominated by European immigrants and an important influx of Middle Eastern and Jewish immigrants.

As a result, Argentina has strong regional cultures, but the strongest cultural influence belongs to Buenos Aires. This is where Argentina unites as a country. This is where the political and economic power resides. Though there are significant social and psychological barriers between the city and the rest of the country, Buenos Aires is where things start. That was also true for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[3]

Shortly after the Church was established in Buenos Aires, missionaries made two attempts to expand missionary work among indigenous peoples in northern Argentina. Elders J. Vernon Sharp, Douglas B. Merrell, and Lewis E. Christian went to Jujuy in the far north, and Elder Waldo Stoddard and President Reinhold Stoof went into the Gran Chaco in the northeast. The attempts were unsuccessful, and the Church would not expand north until thirty years later. The Church was permanently established in Rosario in 1930, Córdoba in 1938, and Mendoza in 1940. But for the most part missionaries stayed near Buenos Aires until after World War II.[4]

The most serious challenge for the Church in Argentina during the early years was the lack of missionaries. Few were sent to Argentina between 1926 and World War II, and most missionaries were evacuated during the war. It was not until the mid-1950s that the number of missionaries sent to South America increased enough that expansion outside the capital could begin in earnest. At that time missionaries went south and west but not north. Supervising the missionaries and members from Buenos Aires was difficult, and Church leaders eventually thought of dividing the mission so growth could occur. In a memorable meeting held in Rosario on May 30, 1956, President Moyle talked about splitting the Argentine Mission by comparing it to Brazil: “I was in Brazil the other day and they asked me there if I wouldn’t divide that mission and give them two now. But I think we will have to give Argentina two before we do Brazil.”[5]

The distance between the mission headquarters and the outlying branches created challenges. For example, in 1954 the branch in Santa Fe, close to Rosario, was closed “because of lack of members as well as unity.”[6] When Loren Pace was named mission president, he focused significant attention in Chile instead of sending missionaries to northern Argentina. Cities were opened around Córdoba and Mendoza. Missionaries were eventually sent north just before he left—to Santiago del Estero and Salta in 1959 and Jujuy, Tucumán, and Resistencia in 1960.[7]

C. Laird Snelgrove, who became president of the Argentine Mission in March 1960, was informed by President Pace that the branches in northern Argentina and its interior were in bad shape. He explained that many of the northern branches were so weak he was not sure they should remain open. The branch in Córdoba, the oldest branch in the area, was in serious turmoil, and President Pace strongly suggested that missionaries be taken out of the city. President Snelgrove made a visit to the city and talked to the leaders of the branch. He did find serious personality conflicts between the members, but his solution was different. He divided the congregation into two branches, essentially separating the conflicting parties, and he sent more missionaries to the city: “That was the solution to the problem. We rented new halls and put missionaries there and told them to go out and find members to fill the buildings. And that got Córdoba off of this negative attitude and negative opinion.” The problems subsided with increased emphasis on missionary work. President Snelgrove also sent more missionaries into the north and opened several cities. Instead of closing branches, the north became a region of expansion. Sister Snelgrove said, “That’s where we had so much growth.”[8]

It was in western Argentina that President Snelgrove had one of the most significant spiritual experiences of his mission. There were missionaries in the cities of Mendoza and San Juan but nowhere else in the region. On June 25, 1960, President Snelgrove was on his way to visit the area, and one of the stopovers was in San Rafael, a city south of Mendoza. As the plane ascended it banked in such a way that President Snelgrove had a full view of San Rafael and could see the activities of the people on the street. The following impression came to his mind: “There are thousands of good people down there whose lives are to be changed by the gospel. They are not aware of what will happen, and have never heard of the Church. This all depends on you!” As soon as he returned to Buenos Aires, he sent missionaries to San Rafael. Within a month there were several baptisms, and by the time he left Argentina a year later, there were almost one hundred members of the Church in the city. Experiences such as this led President Snelgrove to believe that the Church would grow rapidly in northern and western Argentina.[9]

By the end of 1961, President Snelgrove felt that the mission must be divided and made the request during the visit of President Joseph Fielding Smith and Elder A. Theodore Tuttle. The three spent two weeks together in Argentina and visited all of the major cities. During one meeting, they decided where the headquarters of the new mission would be. Looking at a map of Argentina, President Smith said, “‘I can tell you now where the headquarters of the new mission will be,’ and then he pointed to Córdoba.”[10]

Forming a new mission was not an easy task. The number of missionaries in the mission had to be increased. By the time the mission was split in 1962, the number of missionaries increased from 120 to more than 190. Each mission was given an equal number of missionaries. With the new missionaries, new areas and cities were opened. This significantly increased the number of missionaries in what would be the North Argentine Mission. Districts were organized in Mendoza, Córdoba, and Tucumán. The branch in Santa Fe was reopened. Missionaries were sent into the northern area of the Gran Chaco, Resistencia, and Roque Sáenz Peña. Slowly the members and missionaries prepared for the split.[11]

Shortly after the Stones received their call from President Moyle, they began preparing to serve. Getting visas to enter Argentina took time, but they eventually received a unique visa, permanent residency, allowing them to stay in Argentina as long as they wished, which they said was “the first time in the history of the Argentine Mission.” They visited U.S. mission presidents in California and the Northwest to learn as much as possible about being a mission president. They were set apart in Salt Lake City on August 30, 1962, and by September 7 they were in Montevideo, Uruguay, where they spent three days with Elder Tuttle. When President Stone presented his ideas to Elder Tuttle on missionary work and getting local members into the leadership of the Church, he was pleased with the reaction: “He [Tuttle] was amazed that I had come down with practically the same ideas and intentions as they were projecting for all of South America.”[12]

After spending three days in Buenos Aires with President Snelgrove, the Stones drove to Córdoba, the new mission headquarters. They moved into a semifurnished home, “which [was] an old, once elegant home, rented for the time it [took] to build a new mission home.” That Sunday Elder and Sister Tuttle arrived and held the meeting to divide the mission. The missions were divided along district lines. The boundary was to be between Rosario and Córdoba with the former staying in the Argentine Mission. The new mission included the district of Mendoza and the entire northern part of the country. This exceptional meeting set the tone for the evolution of the Church in this part of South America. In his talk Elder Tuttle challenged the members and the missionaries to realize an important goal: “We need to bring people into the Church so that the organization of the Church can perfect each individual. . . . Work willingly, learn responsibility, be loyal, have faith, and share the gospel with all whom you must for the eventual formation of a stake here. We need not take so much time to build a stake as formerly. It has taken since 1925 to prepare Buenos Aires for stakehood, but I predict that you will have one here within three years.”[13]

The following day a conference was held with the missionaries of the new mission. Elder Tuttle attempted to relieve minor worries some missionaries had about the age of their new president, saying, “President Stone is a young man. He is enthusiastic. . . . He is talented. He is an excellent administrator. He is courageous, talented in music, full of faith and dedicated to the work of the Lord.” He also commented on something else that was on the minds of the missionaries: “Sister Stone is very talented. She is a noted singer. She is also young. You will probably have to pin a note on her and say that she is not a lady missionary but the mission mother.” Elder Tuttle ended by suggesting that the mission and the mission president were both young, “but you can grow together.”[14]

President Stone’s message to the missionaries indicated what he wanted to happen in the mission. His primary goal was to have the Church function under the direction and control of the local Argentine members. For this to happen, he said, “the missionaries are to only proselyte.” With an increased emphasis on missionary work, the Church would grow, develop, and flourish. The result would be the organization of the stake predicted by Elder Tuttle.[15] When the Tuttles left on September 18, the Stones were already working toward those goals.

Public Relations

Among the many challenges involved in missionary work was the problem of recognition and acceptance. The constitutionally recognized, official religion of Argentina was Catholicism. The Catholic Church had always been protected by the state, and the introduction of other religions in the country had not been easy. Many Argentines felt that the cultural connection between Catholicism and Argentina was so important that conversion to another religion was paramount to rejecting their culture.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had experienced challenges with its image for many years. The early members of the Church in Buenos Aires were primarily German and Italian immigrants who were poor and lacked formal education. Attracting higher-class members to the Church was a challenge. The failure of the Church to invest money in the construction of chapels meant that the meetinghouses used often did not attract converts with high standing in the community. This did not seriously hamper those who became converted to the gospel, but it did hamper efforts to attract more middle-class investigators. This was particularly true in the northern areas, where missionaries were new to the region. It was difficult to explain to investigators why meetings were held in small, rented homes.

Improving the image of the Church was a delicate issue. Elder Tuttle and President Stone did not want people to think it was merely a North American religion. That in itself could be detrimental to attracting converts. But both were concerned with the social makeup of the Church membership. During Elder Tuttle’s first visit to Argentina with President Joseph Fielding Smith, he noted the heavily female congregations with very few families. Elder Tuttle and President Stone decided one of their major goals would be to change the demography of the Church. They wanted to baptize more complete families. They encouraged more proselyting among people with a higher educational and social level. They wanted new members with leadership and management experience so they could easily move into administrative positions in the Church. They wanted to quickly upgrade the social level of the Church.[16]

Unlike the majority of the converts who came to the Church, the missionaries presented a different image. They were, for the most part, young, middle-class Americans wearing white shirts and ties. Consequently, the missionaries often attracted the attention of middle—and upper—class South Americans who spoke English and were interested in international experiences. They may not have had interest in religion but would make contact with the missionaries because of their background. As one mission president stated, “There are all sorts of talents that our missionaries are blessed with—athletics, music. We ought to use them to teach the people.”[17] The challenge during this period was to find a way to use the missionaries’ backgrounds as a proselyting tool while at the same time deemphasizing their Americanism.

The talents of missionaries had been used to attract investigators to the Church since the first mission was opened in South America in 1925. One of the earliest ways of attracting potential investigators had been to offer free slide presentations on the United States, Utah, and Native Americans. After the show, those participating would be invited to return to a sacrament meeting or a presentation more directly related to the Church. Elder Rey L. Pratt, one of the first missionaries in Argentina, often used this method.

In Argentina and Brazil, early missionaries offered free English classes in the chapel, often just before a Church activity such as a young adult meeting. Those attending English classes were often required to remain for the religious activities if they wanted to continue attending the language class. In terms of conversion, this method took time, but many young converts came from those early English classes.[18]

By the 1960s, English classes were not used as much because of the time spent away from proselyting. When they appeared to work, they were used. One case was in the Rodó Branch in Uruguay in 1961. President Fyans reported that because of a large number of requests to teach English classes, he decided to allow the missionaries to do so, but not without a payback: “An exchange plan was set up where by those who enrolled in English classes must also attend gospel classes for a comparable period of time. Any Church member who attends the classes must bring a nonmember as an ‘admission fee.’”[19]

A second opportunity to make contacts was athletics. Many missionaries had participated in sports programs in the United States, and some had played college basketball. Mission presidents saw their involvement with athletics as a way to contact young middle—and upperclass men. Some missionaries were encouraged to join athletic clubs and join local teams to increase contact with the young men in the clubs. Occasionally missionaries offered to give classes in sports, primarily basketball camps, in much the same way they had offered English classes. A few times they organized mission basketball teams that competed with the local teams. Missionaries were sometimes asked to play on local teams, particularly during important championship tournaments. Tall, talented American missionaries were a way for local teams to win. All these activities were kept to a minimum, so that proselyting time was not overly affected.[20]

Probably the most effective use of sports with proselyting was in Uruguay. Part of the reason the Church was so readily accepted in Uruguay was because one missionary from Argentina had helped a local team win a national championship in 1939.[21] Before President Fyans came in 1960, several of the missionaries had played with local teams on a regular basis. Some missionaries served their entire missions in Montevideo so they could be available to play basketball.[22] President Jensen had said that based on an examination of conversions, missionary participation in athletics did not result in many converts. President Fyans, however, soon realized that the Church had a reputation in the area of basketball, and some of the missionaries had become local celebrities. One such player was Elder Verl Pierce.

Elder Pierce had been released from his mission for some time and was working in California. A representative of a local athletics’ club, Club Penarol, told President Fyans they were in a difficult stretch of the season and needed a basketball player like Pierce. When President Fyans indicated Pierce was in the United States, they offered to pay his way to Uruguay and give him a salary equal to what he was making in the United States. Pierce agreed and was flown to Montevideo, played a few games with the team, and helped them win the games they needed, becoming somewhat of a local hero. His play became front-page news, and the Church experienced a significant boost in publicity. Several other clubs throughout the country approached missionaries with proposals to play. These requests were generally not accepted due to the time required.[23]

President Fyans was approached by a local athletic club with an offer that the missionaries could not only play but also teach basketball to the youth. He decided to allow a few of his missionaries to become involved on a minimal basis. But he had one requirement: the missionaries would teach the gospel too. He explained to the heads of the club that missionaries were not in Uruguay to play basketball, “but if you will trade us eight hours of your time . . . in a series of eight one-hour meetings, we’ll give you basketball players.” Some of the clubs accepted the exchange. President Fyans was pleased with the arrangement: “Now He [the Lord] has placed in our hands thousands of young men through this basketball training program, and he has given us our stake presidencies, our high councilmen, and our bishoprics, and we just hope we can be equal to the challenge that is before us.”[24]

Another sports venture was the Brigham Young University basketball team’s tour of the South American missions during the summer of 1965. The tour was to develop better relationships between the United States and South America and “to represent the Church and to offer opportunities for the missionaries in proselyting.” The missions handled much of the public relations arrangements and made sure the Church was prominently mentioned in the newspaper reports. Two missionaries accompanied the team as guides and translators. At the games the missionaries handed out tracts, and a missionary quartet sang at halftime. In some locations members formed cheerleader groups to support the team. Missionaries felt the visits helped their work, reporting, “The public acceptance of the team was very good and a great aid to the proselyting.”[25]

The actual effect of missionary participation in athletics is difficult to determine; however, there was also a negative effect. There were always two sides in an athletic competition, and antagonism was often created by having Americans play. President Fyans noted a serious problem in Uruguay because of those athletic events: “We found that we were not necessarily continuing the popularity by continuing to win. There were demonstrations against the missionaries. Tremendous things occurred that were negative.”[26]

In contrast to sports competitions, one program with minimal negative reactions was music, which had been used as a missionary tool for many years. President Williams, when opening the Uruguayan Mission in 1949, formed a quartet made up of him, his wife, Corraine, and daughters Barbara and Argina. They toured the mission singing at programs and on the radio.[27] Elder Tuttle encouraged these types of programs, and singing groups, mostly quartets, were formed and tours made in every mission. One group, the Mormon Moderns, toured all the South American missions in 1962–63, putting on concerts for Church members and members of other faiths. They sang on television and radio and even produced a record sold throughout South America. President Stone was pleased with the attendance at concerts in the Argentine North Mission but was concerned about the amount of time it took: “The only disadvantage to the quartet was that we depended on our own full-time missionaries too much in most cities. . . . It took them out of the proselyting work and resulted subsequently in a drop in baptisms all over the mission.”[28]

The Mormon Boys

The challenge of name recognition in the North Argentine Mission was so serious that President Stone decided to try a program that was to bring significant attention to the Church. He organized the largest traveling musical group in all of South America, the Mormon Boys. President Stone was a musician who had put himself through college by organizing and directing his own dance orchestra. When he came to Argentina as a missionary in the 1950s, he traveled by boat and was instructed by his mission president to bring all the musical instruments he played. He brought with him an alto sax, tenor sax, clarinet, and ukulele. He used his music the first night he arrived, when he was asked to direct the choir for the member district, preparing them to sing for a special Christmas radio program. He played all the instruments he brought with him when the mission organized a dance orchestra. He also recognized the amount of work this required because work on the orchestra was done after a full day of regular missionary work.[29]

When President Stone returned as mission president, his focus was on organization and administration of the missionary work and local member organizations. Missionaries were allowed, however, to use their musical talents to bring positive attention to the Church as long as it did not interfere with proselyting activities. Sister Stone sang on a nationwide radio program within two months of their arrival. President Stone’s comment after this broadcast showed his desire to use the media to help open the Church in this region of Argentina: “We are confident that this will open the door to many future contacts with the radio stations in Northern Argentina. . . . We are looking forward to an active proselyting program through radio throughout the nation.”[30]

Within a few months, President Stone realized there was significant musical talent among his missionaries. He wanted to develop a show band similar to one he had in the States, so he surveyed the mission to determine who the musicians were and transferred them to Córdoba. The members of the band understood his purpose: “Since this was a brand new mission, he [President Stone] recognized the need to ‘make a lot of friends.’ That was the main reason he allowed us to form a band—to make friends.”[31]

In February 1964 the nucleus of the band began limited practice. Following President Stone’s guidelines, the time spent practicing was in addition to regular proselyting, occurring mainly on their one day off (diversion day). Eventually they formed a twelve-piece show band playing traditional Argentine music and U.S. band tunes. They even created their own arrangements. Practice began in earnest during January of 1965, and their first performance was to a mission youth conference that same month. The concert was a hit.

Later they were allowed to expand their practices into the traditional Argentine siesta time, when missionaries did not normally go out. Usually during this time missionaries ate lunch and studied the language and scriptures. With the increased practice time came a caution—the activity was to be secondary to their proselyting work. A member of the group, Elder P. K. Anderson, stated: “President Stone told us we could sharpen our musical skills and presentation as long as we kept bringing in new converts, at least at the rate of the other missionaries in the area.”[32]

Within a month President Stone decided the group could significantly help the mission. He moved all twelve musicians into a house close to the mission home. They started playing at events around town, including basketball games between local clubs and missionaries. President Stone was able to negotiate the use of a jeep for their transportation, using non-Church funds. He approved stopping their normal proselyting activities, instead concentrating on practicing and getting ready for their performances. Though this type of focus was necessary, it was not easy on the missionaries. One band member stated: “There were times when many of us felt that other missionaries and our relatives and friends did not appreciate the value of our mission. In fact, even some of the younger members of the band had a rough time being pulled completely out of regular missionary work. They did not see the significance of our work until everything began to actually work and produce tangible benefits.”[33]

The Mormon Boys.

After having played in a variety of places in Córdoba, the group went out on two tours of the mission. The first was in the southern half of the mission, where the Church was more established. One missionary, Elder Lanning Porter, who was responsible for public relations, set up the programs. The local missionaries helped organize and publicize the band events in their cities. However, it was not without challenges. The band would arrive in the town and immediately make visits to hospitals, schools, and television and radio stations. Their concerts were held in the evening. The day activities were at no cost, but the evening program charged admission, enough to pay for the transportation and basic needs of the group. Then the band members and all their equipment would be put into two automobiles, and they would drive to the next town.

Since the focus was on the Church, the Mormon Boys invited the press to all their activities. Their visits to schools and hospitals were often covered by local newspapers. They did not overtly preach the Latter-day Saint message, but did so in the songs. Anderson stated, “We preached with our music, our enthusiasm, and our name.” One newspaper report on their concert in Santa Fe recognized the connection: “They are all North Americans who leave behind them a pleasing scattering and a curiosity to know more about the Mormon sect to which they belong and whose faith they want to spread.”[34]

The second tour, between July 5 and September 3, was more of a challenge. In two months they put on multiple shows in seventeen cities, traveling the entire distance of northern and southern Argentina in their two automobiles. During this tour they encountered significant opposition. In Tucumán, Catholic priests encouraged the town to boycott their concerts, though these activities did not significantly decrease the number who attended. They faced significant opposition in the northern city of Jujuy, with again limited effect on concert attendance. There were also struggles in the northern region of the Gran Chaco. In spite of all these challenges, the group was able to have success. President Stone attributed the surge in growth of the Church in the north to the visit of the group.[35]

When President Stone was replaced by Richard G. Scott as mission president in 1965, the group was disbanded. In fact within a couple of months, due to instructions given by the new General Authority supervisor, Elder Spencer W. Kimball, all musical groups and sports involvement by missionaries were discontinued. For a time, the Mormon Boys had played an important role in the expansion of missionary work into areas where the Church was little known. It put the name of the Church into the public mind in a way that was neither combative nor offensive.

Public Relations

Though improving the image of the Church was always a goal, the method of doing so was almost always left up to the individual mission president. However, near the end of his time in Uruguay, Elder Tuttle developed a plan for public relations that influenced future programs throughout South America. He formed a news service provider called the Servicio de información sudamericano (South American Information Service). This service used missionaries and local members to ensure the press received positive information about the Church. Each mission had its own office run by missionaries. Informative news releases about the Church were prepared in Montevideo and then sent to the missions for distribution to newspapers, radios, and television. Elder Tuttle believed in using all methods possible to promote the Church, saying, “The Mormons are news in South America. The growth is news. The construction of chapels is news—and the way in which we do it is news. Our schools in Chile are news, and the Mormons are coming to be known for their way of life.”[36]

An important part of that project was to make sure Church events were adequately covered. When new missionaries arrived in a city, the local papers were notified. When local members experienced achievement in areas unrelated to the Church, news of their accomplishments was sent to the papers, and their Church membership was always mentioned.

Among the activities covered were visits of Americans, primarily General Authorities. These visits occurred at least annually, and there were always press conferences and receptions. During the visit of President Hugh B. Brown to South America, he held seven news conferences with thirty different newspapers, eight television appearances, ten visits with public officials (including the president of Uruguay), and eight receptions. All of this was in addition to meetings with members and missionaries. The visits of General Authorities were important to the members, but they were also seen as a way to get the name of the Church into the local media.[37]

Occasionally local leaders planned activities to draw attention to the fact that General Authorities were visiting. When President Brown visited the city of Arequipa, Peru, members held a parade from the airport to a conference while missionaries followed on the streets giving out pamphlets. President Brown seemed pleased: “President Brown was very impressed. He states that his reception was excellently planned this day and that he had never been so announced.”[38]

Occasionally those events backfired. In April 1963, Cleon Skousen, Salt Lake City police chief and author of a book on communism, came to South America to pick up his son from the Brazil South Mission. He toured the rest of the missions and gave talks in several cities. The events were well publicized, and good-sized crowds attended his presentations. His talks were strongly anticommunist, and he often made references to the local political scene, particularly in Brazil and Argentina, warning of communist infiltration into their governments. His ideas were not always well received and may have hurt the image of the Church on the outside and inside. His criticisms of former Argentine president Juan Perón were not appreciated. President Stone said, “He gave a straight-forward talk on Communism and human rights. . . . It was difficult for some of the members of the Church to separate their religious feelings from their political allegiances, for Brother Skousen attacked ex-president Perón quite severely, and Perón has many followers yet in this country. As a result, a number of members went inactive for a while.”[39] Most returned after they were able to make a distinction between their own feelings about the Church and one person’s political views.

An event that attracted positive attention was the dedication and opening of chapels. These events were often in conjunction with the visits of General Authorities. Tours of the buildings were offered to the press and prominent citizens as well as the general public. Receptions were held and dinners provided to some of the guests. Packets explained views of the Church and often included numerous pictures. For the inauguration of the first chapel in Córdoba, President Stone felt that the enthusiasm of the members made up for several problems of coordination and organization: “As a proselyting event, it did not come up to the expectations we had hoped for, but for the members it was extremely successful.”

One interesting event held in Uruguay attracted visitors to the Church at Christmastime. For at least two years the Tuttles and the five other American families who lived on the Mormon Block in Montevideo would decorate their homes with Christmas scenes from six countries. In 1965 the Tuttles had an American Christmas theme, including a replica of the Salt Lake Temple along with a nativity scene. More than seven thousand luminarios (brown paper sacks of sand with lit candles in the middle) lined the block. Thousands of visitors went by the homes creating evening traffic jams for a few days. Missionaries were on hand to conduct the tours and hand out pamphlets. One touching scene was noted about one of the Tuttle daughters: “The night before Christmas, while the others were reading and coloring, Lisa went to sleep curled up in a big blue armchair near the fireplace. It looked as though we had posed the scene, and the people who saw her (and there were many) were simply enchanted.”[40]

Radio Carve

Elder Tuttle had a much greater plan than just using the local media to spread the knowledge of the Church throughout South America. In June 1962, the Church purchased a powerful shortwave radio station in New York City called WRUL. They already had a local radio and television station in Salt Lake City, but this was the first station owned by the Church outside the western U.S. It was envisioned that this station would be the first of many broadcasting the message of the gospel to South America. Leaders discussed how to use this medium to supplement the activities of the missionaries.[41]

In 1963, Elder Tuttle was informed that the Church was interested in purchasing a radio station in South America. In October, Ronald Todd from WRUL traveled to South America to find a station. He visited all the countries with members to find a station with a signal strong enough to reach a large population. He hoped to purchase a station in Paraguay because of its central location in the region, but after a visit there he rejected that idea. Elder Tuttle believed Uruguay was the logical place for a station and was able to persuade Todd to look there.[42]

Early in his experience in Montevideo, Elder Tuttle became aware of a positive historical relationship between the Church and a large radio station called Radio Carve. As early as 1948 the station was responsive to the Church and had the mission president’s wife, Corraine Williams, and daughters sing on a weekly basis. For many years this station had given positive coverage to the Church, including having the Mormon Tabernacle Choir broadcasts as a regular part of their programming. It was an AM station with a powerful signal of 50,000 watts that reached well beyond the borders of Uruguay to Argentina and southern Brazil with a potential audience of over seventy million people. It was part of a large conglomerate of four broadcasting facilities that included a television station, a shortwave radio station, and two radio stations.[43]

The stations were owned primarily by Raúl Fontaine and Juan Enrique de Feo. They had no connections to the government or any political parties and were highly respected thoughout the communications world in South America. They were willing to sell the Church 25 percent of the company and allow the Church to broadcast its programs. The Church would have a representative on the board of directors and its own staff members. Other entities were interested in the stations, including the Time-Life Broadcasting Company in New York, though the desired partner was the Church. The cost was $250,000.[44]

Elder Tuttle and others in the Church’s communication departments worked on the purchase of the station for over a year. In the end of 1963, Church officials from Salt Lake City made several visits to work out the details of the purchase. They were so encouraged the purchase would occur that a home was identified for the family of the Church manager of the station. At October conference in 1964, Elder Tuttle wrote a formal letter proposing the purchase to the First Presidency under the signatures of Elder Tuttle, President Fyans, and Arch Madsen, head of Church Communication (later Bonneville International Corporation). The negotiations continued until Elder Tuttle returned to Salt Lake in 1965, when he again pushed for the purchase of the station. The purchase, however, was never finalized, and the Church moved in a different direction related to communications.[45]

Conclusion

The area covered by the Argentine North Mission was large and extensive. The presence of the Church in most of the region was limited to a few small congregations in 1962, when thirty-five-year-old Ronald Stone and his wife, Patricia, took their small family to the city of Córdoba to open the mission. Activities in all areas of the mission resulted in growth, but perhaps the most important accomplishment of his three years as mission president was that the name of the Church was spread throughout the region in a positive way as a result of his public relations activities. By 2005 that small beginning had expanded to many stakes and five additional missions in the same area.

Notes

[1] Most of the biographical information on the Stones comes from oral interviews with Ronald V. Stone and Patricia Judd Stone by the author, December 27, 2000, Modesto, California.

[2] For a description of this experience, see Journal of J. Vernon Sharp, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 64–69.

[3] For general information on Argentina, see Jonathan Brown, A Brief History of Argentina (New York: Facts on File, 2003).

[4] For a summary of the history of the Church in Argentina, see Néstor Curbelo, Historia de los Mormones en Argentina: Relatos de pioneros (Buenos Aires: privately published, 2000).

[5] A copy of the talk is found in the “Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” May 30, 1956, Church History Library.

[6]“Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” Rosario District, April 19, 1954.

[7] Chile was important to President Pace. He visited northern Argentina only after visiting the Chilean city of Antofagasta. He took the train across the border and visited Salta, Tucumán, and Santiago del Estero (“Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” August 25, 1959).

[8] C. Laird and Edna H. Snelgrove, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1987–88, transcript, 47, 84, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[9] C. Laird Snelgrove to Gordon B. Hinckley, July 22, 1972, copy found in the appendix of a history of President Snelgrove’s mission experiences, entitled Argentine Mission, November 2002. Copy in possession of author. It was also included in C. Laird and Edna H. Snelgrove, oral interview, 103.

[10] As quoted in “Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” 87.

[11]“Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” February 8, 1960.

[12]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” September 7, 1962.

[13]“Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” September 16, 1962.

[14]“Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” September 17, 1962.

[15] The organization of the first stake in Córdoba occurred in 1979, seventeen years after the organization of the mission (2005 Church Almanac [Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2004], 268).

[16] A. Theodore Tuttle to South American Missionaries, July 15, 1965; copy found in the Church History Library.

[17] Comment by Gerald Smith, president of the Eastern States Mission (Mission Presidents’ Seminar, June 26 to July 5, 1961 [Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1961], 1:168).

[18] The best example of the effectiveness of this type of approach is the Campinas Branch in the interior of São Paulo, Brazil. Many of the early members joined after participating in English classes (Mark L. Grover, “Mormonism in Brazil: Religion and Dependency in Latin America” [PhD diss., Indiana University, 1985], 77).

[19] “Manuscript History of the Uruguayan Mission,” October 16, 1961, Church History Library.

[20] For a discussion of sports as proselyting tools, see Frederick S. Williams and Frederick G. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree (Fullerton, CA: Et Cetera, 1987), 137–51.

[21] Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 146–47.

[22] Clark V. Johnson, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, April 2001, Provo, Utah; copy in author’s possession.

[23] This experience was described by President Fyans in his presentation given at the worldwide mission conference held in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1961 (Mission Presidents’ Seminar, 1:163–70).

[24]Mission Presidents’ Seminar, 1:166.

[25]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” June 18, 23, and 24, 1965.

[26]Mission Presidents’ Seminar, 1:167.

[27] Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 261–68.

[28]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” July 1963.

[29] Ronald V. Stone, oral interview.

[30]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” November 8, 1962.

[31] P. K. Anderson, The Mormon Boys: A Musical Mission in Argentina (Provo, UT: By the Author, 2001), 23.

[32] Anderson, Mormon Boys, 61.

[33] Anderson, Mormon Boys, 66.

[34]El Litoral (April 1965) as quoted in Anderson, Mormon Boys, 105.

[35]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” July 30, 1965.

[36]“50,000 Baptized in South America,” Church News, October 3, 1964, 10. For a good example of how it worked at the mission level, see the Peruvian Mission newsletter El Chasqui, April/

[37]“Statistics Compiled Re: President Brown’s Tour of the South American Missions, Jan. 9–Feb. 12, 1963”; Copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[38]“History of the Tour of President Hugh B. Brown of the South American Missions, 1963,” in “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” February 5, 1963, Church History Library.

[39]“Manuscript History of the Argentine North Mission,” April 1963.

[40] Marné Tuttle to “Loved Ones,” June 18, 1965; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[41]“Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” December 12, 1963.

[42] Marné Tuttle to A. Theodore Tuttle, October 19, 1963; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[43] Corraine Smith Williams, Autobiography, 1996, 68, Church History Library.

[44] A. Theodore Tuttle, J. Thomas Fyans, and Arch Madsen to the First Presidency, October 8, 1964; copy in author’s possession. For a history of the radio station, see www.carve.com.uy.

[45]“Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” December 12–14, 1963; April 14, 1964; October 7, 1964; November 19, 1964.