I'll Bring Him Up to Serve the Lord

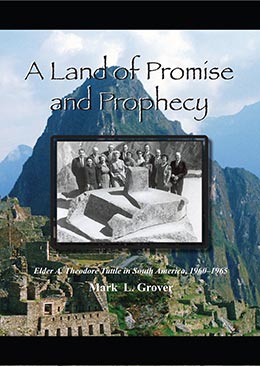

Mark L. Grover, "I'll Bring Him Up to Serve the Lord," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 26–52.

What Elder Tuttle was feeling this fall day in 1960 did not seem right, nor did it fit into his plans. South America was not supposed to be his destiny. Two years earlier he had felt a strong impression he would be working with the Lamanites of the South Pacific, not Latin America. In June of 1960, that feeling had been strongly reconfirmed during a mission presidents’ conference. At least that was the way he interpreted the impression: “I still have the feeling that some day I will follow Matthew Cowley’s footsteps out in the Pacific. Can’t get over the feeling that I am to go on a mission out there. Only time will tell.”[1]

Yet most of the assignments for this newly called General Authority pointed another direction. Since his call to the First Council of Seventy in 1958, he had worked with education, missionary work, and Native Americans. He had visited numerous stake conferences, including the Colonia Juárez Mexico Stake. In February of 1960, he had toured the Spanish American Mission with President and Sister Hugh B. Brown.[2]

That fall he received the unusual assignment to tour the South American missions for three months, beginning on October 13. It was not an easy assignment because he would be without his wife and family for a long period and be away from home during the holidays. He was to accompany Joseph Fielding Smith, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and his wife, Jessie Evans Smith. He thought he was asked to go on the trip to carry their bags. After being on a ship with them for several days and having read more than half of the Book of Mormon, focusing on the promises found in this volume of sacred scripture concerning the inhabitants of the Americas, he had an experience that both surprised and unsettled him. One day as he said his evening prayers, he had the distinct impression: “You are going to be in South America, and you are going to preside in that area.” His response was, “Oh no, not me.” He did not know Spanish, and besides if he was going to go anywhere, it was supposed to be to the South Pacific. “So in my prayer I told the Lord no, I won’t go.”[3]

That evening began a wrestle with the Lord. He placed before the Lord all the reasons not to go. He was not qualified. He did not know the language. He did not know anything about the place and frankly did not want to know anything about it. He lacked experience. He had never served as a mission president. He had six young children, and they had just moved into their new home in Pleasant Grove, Utah, designed to be their dream home. Finally Marné was pregnant with their seventh child. It did not appear to be a good time to go to South America. He needed more time. On and on, the reasons multiplied as he continued his pleading. He stayed on his knees for a long time, but to no avail. Finally when no alternative was offered to him, he promised the Lord, “All right, I’ll do it, and I’ll do it gladly.” From that evening on, his letters to the family included hints of the adventure all of them were soon to have.[4]

Thus began one of the great missionary stories in the history of the Church. Elder Tuttle would never get that assignment to the South Pacific, but he did become a sort of Matthew Cowley to South America. During his twenty-eight years as a General Authority, three assignments resulted in his living in Latin America for more than seven years, and his influence was to be profound in all aspects of the growth of the Church there.[5] These years in South America began a period of growth and development in missionary work and organizational development never before seen in Latin America. The growth and expansion have continued in an unparalleled fashion to the present. In 1961, when he arrived in Montevideo, Uruguay, as president of the South American Mission, the Church population in that region of the world represented a mere 1 percent of the membership. During his service, the population of the Church in South America more than doubled in size. By the year 2000, more than one-third of the Church lived in Latin America. Indeed, the story of the Church in Latin America is one of the major events of the Church in the twentieth century.

Growing Up

For those who knew Ted Tuttle, it is difficult to think about him without thinking of Marné Whitaker Tuttle. Since their marriage in 1943, they were always a team in everything. Both came from families who had struggled with the economic difficulties of the Great Depression. Both came to Brigham Young University with dreams and aspiration to serve the Lord to the fullness. Their goals and objectives in the Church were the same as they had with their family. It was a marriage marked with love and devotion for each other and the Church.

Ted Tuttle was from central Utah. His mother, Clarise Montez Bean, was raised in Richfield but moved to Ephraim to work and attend Snow Academy, where she met and married Anthon Peterson in the Manti Temple. Three weeks after their marriage, Anthon was killed in an unusual accident in the alfalfa hay fields, so the grief-stricken new bride was left alone. So affected was Clarise that a trembling in her hands became a constant reminder of that traumatic event. Marriage came again after three years when she met and married Albert M. Tuttle, Ted’s father, a sheepherder in Manti. They remained in Manti to raise their family.[6]

Ted's mother, Clarise (right).

Ted's mother, Clarise (right).

Having children was not easy for Clarise. She waited three years before Helen, her first child, was born and unfortunately died at birth. Another three years resulted in the birth of June, Ted’s older sister. At this time, realizing her difficulty conceiving and fearing she would never have a son, she prayed to the Lord with a promise, “If you can grant me a son, I’ll bring him up to serve the Lord.” That prayer was answered with the birth of Albert Theodore on March 2, 1919, and she complied with her Hannah-like promise (see 1 Samuel 11). She made sure her son was taught and trained properly so he would be able and worthy to serve the Lord as she had promised.

Because of the nature of his birth, Clarise always felt her son had a special calling to carry out for the Church. Consequently, Ted’s training as a child was full of lessons and examples. Clarise was very active in the Church and made sure that Ted attended all his meetings and participated in all Church activities. His father was not as faithful during these early years but supported his wife, June, and Ted. Early in his life, Clarise taught Ted how to speak in public. She would put him at the far side of the room and say, “Now speak up. If you want to be heard, you might as well speak up; otherwise sit down.” In this way he learned to project his voice. She volunteered Ted for every Church assignment that came along, particularly talks. An understanding of the gospel and testimony of its veracity came early and easily to Ted due to his mother’s strong influence.[7]

Learning how to live with limited resources was also one of his early lessons. His father’s sheep ranch was prosperous, and with the help of bank loans it eventually expanded to almost two thousand head of sheep. With the stock market crash in 1929 and the resulting financial crisis, the Tuttle loans came due without the capital to pay. A twelve-year-old Ted vividly remembered the day the bank requested his parents’ signatures turning over ownership of the family’s sheep to the bank. His angry mother at first refused to do so. He wrote, “I remember Mother crying—and it was seldom that I remember that happening—and so she cried and finally signed it. I remember what a great emotional experience that was, both in my life and in our home on that occasion.” Never go into debt became a motto repeated often in the family from that time forward. It was a lesson he practiced throughout his life.[8]

After losing his herd, Albert Tuttle made a living buying and selling livestock. Though he never made much, the family always seemed to have the necessities. Clarice was a good manager who was able to make do with what they had. The family always planted a large garden that provided food for much of the year. Ted had little variety in the clothes he wore, and he learned from his mother that patches were honorable. “I didn’t ever feel poor. Being poor wasn’t an issue. We just couldn’t have ‘things’ and that’s all there was to it. We understood this without thinking that we were poor, because there were a lot of people poorer than we were.”

Ted’s father was a kind and tender man, concerned with the plight of others and always looking for ways to help those in need. Produce from their garden often found its way into the homes of many of their neighbors. Albert was probably generous to a fault. Ted stated, “I’ve heard people say that if he had a million dollars he’d be broke very shortly, because he was so kind to people. He just shared things.” His success in business was probably affected by his practice of giving. Some friends suggested he was too generous to be wealthy.[9]

Ted was a late bloomer both physically and emotionally. He characterized himself as the “littlest deacon.” He struggled to understand what the older boys were talking about. Actually this may have been from a lack of experience. Physically he was shorter than most his age, so participation in sports was limited. His mother encouraged him to become involved in drama, music, and forensics. He participated and won many local speaking competitions, including the seminary oratorical contests. He volunteered (or was volunteered by his mother) to talk in Church whenever possible, and his talks were always memorized. He took part in almost every play and operetta in high school, though never as the lead. In high school he sang baritone in a vocal quartet that continued into college and was known as the Snow College Quartet.

Ted at age eight (right).

Ted at age eight (right).

An important figure in Ted’s early life was his seminary teacher and stake president, Leland Anderson, a great storyteller who loved the scriptures. President Anderson combined the right amount of humor with enthusiasm and spirit to bring the stories of the prophets to life. Ted loved seminary, and his mother would ask at dinnertime, “What did Leland A. say today?” So the lesson of each seminary class became a major topic of conversation for the family. Thus, at a very early age, Ted knew what he wanted to do as a profession: teach seminary.

Maintaining that goal was not always easy. One evening after sacrament meeting he was talking with his close friends. They had been working in northern Utah for the summer and had developed some new and unfamiliar habits. They asked Ted if he wanted to go with them to purchase a half gallon of beer. He was shocked and said no. Their response was to walk away, leaving him alone. He knew he was right but was still hurt to be so easily left out of the group. Tears flowed. He was the only one who did not participate in this activity and for a while was ostracized for having a “holier-than-thou” attitude. Their respect and friendship were later to return as they recognized that what he had done was correct. The ability to make the correct decision on the spot continued to be a trait throughout his life.[10]

His likable personality resulted in many friends and a certain level of popularity when he reached high school. He was involved in most activities outside of sports. His senior year he was both seminary and student body president for Manti High.

Ted at age eighteen.

Ted at age eighteen.

College and Mission

After graduation, he enrolled at Snow College, where he continued in a variety of activities. He did well in the classes but had one problem. He did not accept the advice of counselors to follow a specific career but instead took classes in a variety of subjects. A unique composite major of history, sociology, and economics had to be created especially for him so he could graduate from Brigham Young University. Ted was a generalist, not a specialist. He pursued interests in all directions. He was not too fond of reading: “My life was oriented to activity rather than sedentary of pondering and contemplation. I just didn’t find much enjoyment in just sitting down and reading a book.”[11] He also took every religion class offered, so many that the institute director refused to report them all for credit to the records office at Snow College.

One thing he knew for sure: he wanted to serve a mission. Money was the only stumbling block. At that time the Church required that the family have enough money already identified to support the missionary before leaving. Ted’s father did not have the required amount, so his bishop, following instructions of the Church, indicated he could not go. Not satisfied, Ted asked his neighbor, Tom Anderson, if he would be willing to help support him on the mission if needed. Anderson consented and, armed with this promise, Ted returned to the bishop and submitted his mission papers. The promised help was not needed, and Ted’s father was blessed to be able to support his son completely.[12]

Elder Tuttle expected to go to Germany, having already taken five quarters of German in college. But world events made that call impossible. On the day he received his call, September 3, 1939, France and England declared war on Germany. Missionaries were not being called to Europe, so Ted was sent to the Northern States Mission headquartered in Chicago. His mission was both satisfying and disappointing—satisfying because of what he gained but disappointing because of what was not accomplished. He said, “We didn’t do much missionary work, it seemed to me.” Not only did they not have many baptisms, they seldom talked about baptism: “That didn’t seem to be the philosophy. If they [the investigator] wanted to be baptized, they asked to be baptized now that the time had come.” Ted believed the most significant missionary work for the Church had already been done, saying, “We were gleaners. The harvest had been made by Wilford Woodruff in the early days of the Church, and in 1939 and 1940 we were gleaners. There were a few left of the children of Israel and we’d find them. . . . So we weren’t supposed to baptize very many, because there weren’t very many to glean.”[13]

He served in several leadership positions, including branch and district president. Returning home September 18, 1941, he had two important objectives left to accomplish: finish school and find a wife. Another activity loomed in his future, military service, because World War II was anticipated. He believed his two goals could be sandwiched between the time he served his country. He immediately registered at Brigham Young University, hoping to finish some schooling before joining the military. He had signed up for the military draft in Detroit while on his mission, so after returning home he waited for his call to enter the war while going to school. A draft notice followed him home, arriving ten days after he did. He received nothing else from the government, however, so he finished fall and winter semesters at Brigham Young University. In April 1942 he learned that his records had been lost and that the draft process had to begin anew. This time, instead of waiting Ted joined the Marine Corps and signed up to go to Officer Training School. They let him finish his senior year in school before reporting for duty. Entering the Marine Corps in August of 1943 allowed him to reach his first goal, to graduate from Brigham Young University. At the same time, he missed two years of the war.

His second goal was also reached. At Brigham Young University, Ted was socially active. He wrote to two young women on his mission, both of whom decided to marry before he returned. During the first week of school after his mission, he went to a dance at the Provo Fourth Ward and met a new student who had just arrived in Provo from the state of Washington and was the friend of a sister of a missionary from his mission. They danced, and he was impressed. But they moved in different social circles, and their paths did not cross much for several months. Marné Whitaker, though, kept an eye out for this young returned missionary who “was a fine dancer and had a lovely smile.”[14]

Marné Whitaker

Marné Whitaker was a descendant of Latter-day Saint pioneers whose family had left Utah. Her mother, Dora Edith Boyce, was born in Granite, Utah, and was raised on an eighty-acre fruit farm. After high school she taught school in Kanosh, Utah, when she met a local boy, Wilford Woodruff Whitaker, who was working while waiting for his mission call. He liked Dora and asked her to wait during his mission to the Northwestern States Mission. The mission was an important experience for Wilford, in part, because his mission president was Melvin J. Ballard, soon to be called to the Quorum of the Twelve. Wilford and Dora were married in July of 1919, after which they moved to Croydon, a small town in northeastern Utah that was close to the town of Morgan. A little over a year later, Marné was born, the first of nine children. Her grandmother, who was present at her birth, believed Marné would be “a child of destiny” because there was a soft film over her face.

Marné Whitaker in college.

Marné Whitaker in college.

The family moved often as Wilford went from job to job, a common pattern during the depression for families who did not own a farm. After working for two years in the Magna Smelters, he became dissatisfied with the work and moved back to Kanosh. It was in Kanosh that Marné first went to elementary school. In 1927 Wilford tried to go into the soft drink business. When that was unsuccessful, he rented a 325-acre cattle ranch in Lamoille, Nevada, and the family left Utah. When the lease on the ranch ran out in 1932, the family moved to Elko, but jobs were hard to find. “Even though we didn’t go hungry in Elko,” Marné remembers, “our living conditions were minimal and we were glad for beans and potatoes, fixed in every conceivable way by my enterprising mother. There were no bathrooms or running water in the first house. Few friends.”

Marné’s mother worked hard to make life as normal as possible. School was enjoyable, and Marné did well. She was involved in a variety of nonschool activities such as 4-H clubs. She took violin lessons for a while. The family loved to sing accompanied by her mother. There were many sweet and tender moments with her mother. When she started to date and asked her mother’s advice on how to act, what she received was confidence: “Marné, I trust you. You know what is right. I’m sure you will make the right decisions.”

During the summers of 1936 and 1937, she stayed at her friend Alice Gardner’s hay ranch in Ruby Valley, Nevada. The two helped cook and prepare meals for the farmhands. One time she found out the Native Americans who worked on the farm did not like Jell-O. Another experience made a lasting impression on Marné. It was her misfortune to find Alice’s father after he passed away while feeding chickens. “It was a sad time. I tried to tell Alice that she would see him someday again, but I lacked sufficient gospel knowledge to really explain about the Resurrection and temple marriage.”[15]

These were not easy times. “I remember the depression years as being a gray time. As the oldest, I felt my responsibilities early and knew it was up to me to ‘pull myself up by my bootstraps.’” In 1936, when times became unusually difficult, Marné’s mother sent some of the children to Salt Lake City for a year so they could go to school. They lived in a small apartment, and Marné tended a young boy while going to school. Marné attended East High School as a junior, took Spanish, and enjoyed the city environment.

When they returned, her father decided to leave Nevada and asked his former mission president, Elder Melvin J. Ballard, where they should settle. His advice was to go to the Pacific Northwest. They packed everything they owned into a large truck, including their piano, and headed north. There were seven children ages three to seventeen. They stopped in Springfield, Oregon, but when they realized the land they hoped to farm flooded almost every year, they continued until they finally settled in town of Wapato in the Yakima Valley, Washington. There Marné worked in a variety of jobs, including picking hops and apples. Her father eventually leased a farm and was able to make it profitable, especially during the war years. With some of the money made working, Marné was able to buy a new dress and shoes and entered Wapato High School for her senior year. Marné enjoyed herself, being active in many school activities and having numerous friends. She took shorthand and typing and worked part time for the principal.

After graduation from high school in 1938, she remained at home to help her mother, who had just given birth to twin boys. She worked sorting potatoes, picking fruit, and canning. She dated a non-Mormon boy fairly seriously but was not interested in marriage with him. Her mother’s example was important in her decision. “I’d made a vow early in my life to marry a returned missionary in the temple, like my Mom did, and he didn’t fit.” There was the possibility of conversion of this young man, but Marné was not interested enough in him to try to get him to join the Church. A returned missionary with experience in the Church was what she was seeking.

She spent the next couple of years working in a variety of jobs in Washington and attending school at the Yakima Business College. Then she spent a few months in Salt Lake City working at a department store. During this time she auditioned with J. Spencer Cornwall and was invited to sing with the Tabernacle Choir but had to decline. She was surprised and decided they were hard up for singers. Suitors came by, and she had proposals for marriage, all turned down. She continued to take classes in bookkeeping and office management and became a proficient secretary. She was not sure exactly what she was waiting for but knew she must be patient for it to happen.

Finally a dream came true. In 1941 her father, sensing that a major change was needed in her life, offered to pay one year’s tuition and three months’ room and board at Brigham Young University. Would she be interested? “Would I?” she remembers. “It was an answer to prayers. Up until that time, it seemed like I was just drifting, with no real goal in sight.” She packed her belongings into two suitcases and headed for Provo, where she registered for the fall 1941 quarter.[16]

Marriage and the Marines

Nothing happened between Ted and Marné for a year. She eventually became a part-time secretary to Franklin S. Harris, president of the university, and with this job Ted and Marné began to see each other. Marné seriously dated another young man who asked her to marry him. Unsure of her feelings, she asked for time so she could think clearly. During this period she spent some time with Ted, including cooking a dinner for him. Unbeknownst to Marné, as she was struggling with the decision of marriage, Ted was feeling serious about her. Part of his interest came after some friendly counsel from President Harris: “Marné is a choice girl, steady, confident, and one of the sweetest girls I have ever known. You could do no better if you are looking.”[17] Marné turned down the other young man’s proposal.

She and Ted began dating, and after a few months they became engaged on June 7, 1943, the day before Ted graduated. On that night Marné recalled a dream she had a few months earlier: “In my technicolor dream I was sitting on a sunny hill under a big tree, and someone had his arm across my shoulders. I couldn’t see who it was. I remember, almost to this day, the feeling of safety and warm comfort I experienced in my dream. I then recalled how comfortable and at peace I was and joyously happy when with Ted, even at this crucial time.”[18]

She was with him when he spoke representing the senior class at the senior banquet. They decided to get married soon because Ted was scheduled to enter the Marine Corps in August. They were sealed in the Manti Temple on July 26 and had a reception at the Tuttle home that evening. After ten days of honeymoon, Ted left for Parris Island, South Carolina, for boot camp, and Marné returned to Provo, “hardly realizing I was really married.” She returned to her apartment, where she lived with her old roommates and continued to work for President Harris. She enrolled for classes and waited for the phone call allowing her to be with her husband. That call came in mid-November after Ted had, in his words, “survived” basic training and was assigned to officer training school at Quantico, Virginia. Marné quickly gathered her belongings and took the long bus ride to Virginia, arriving on November 20, 1943. A taxi driver knew of a place to rent and took her to the apartment. She also interviewed for and was offered a job as a photo studio receptionist. All this was done before seeing Ted, who was on bivouac when she arrived. “When I finally saw this handsome Marine, who had grown taller and heavier, I not only had an apartment for us, but a job on the Marine Base!” Ted was impressed with his new bride’s ability to get things done.

Ted and Marné.

Ted and Marné.

After three months of officer training where Ted graduated in the top in the class, Marné and Second Lieutenant Tuttle made their way west by train to Los Angeles, where he met for the first time his in-laws, they having been unable to attend the wedding. Marné got a job in a department store and soon began to feel morning sickness, saying, “We were thrilled, but knew we would be separated possibly when the baby was born.” In August 1944 they said good-bye when Ted left for the South Pacific to participate in one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific, the Battle of Iwo Jima. Marné’s feelings were poignant: “I have a hard time thinking of the ‘war years,’ because mostly all I remember doing was praying that my sweetheart would return home safely. I could not fathom even for an instant that he would not. I would repeat almost constantly, ‘I love you, I love you, I love you, Ted, and I love you, Heavenly Father, for watching over him!’”[19]

She had reason to worry. Ted was a member of the 28th Marines, 2nd Battalion, Fox Company, assigned as liaison officer for his unit. They set sail aboard the USS Sea Corporal, arriving in Hilo, Hawaii, on September 19, 1944. Intense training was interspersed with leisure time to see the island. Ted was instrumental in organizing a group of the Church for which he was the group leader. Sunday meetings generally had close to one hundred soldiers in attendance.[20] When the training ended, they boarded a ship heading for the war. Ted continued to make sure Church services were held on ship up to the day before they invaded the island of Iwo Jima, saying: “I had a feeling of expectancy something big—yet undesirable—this being my first actual battle where the enemy was shooting at me—and still I wasn’t nervous—physically. There were many tasks that needed doing, much to be done in the way of briefing which on the ship didn’t leave too much time for thoughts.”[21]

After five hours of naval bombardment of the island, the men prepared for the invasion. Ted gathered all the Latter-day Saint soldiers together on the bow of the ship for one last prayer together.

The invasion took a terrible deadly toll as the troops were under a constant barrage of gun and mortar fire. “It was an inexpressible sensation to be in your hole and feeling shells land all around you,” he wrote. He was hit often by sand and rocks caused by shells landing close but was never injured. Many of his friends were not so fortunate. Fourteen of his Latter-day Saint colleagues were killed during the first wave to hit the beach. Part of his responsibility was to be the Graves’ Registration Officer and as such oversaw the recovery and identification of the casualties of war. What a difference from a year earlier when he was a carefree senior at Brigham Young University to now find and identify the remains of his friends and fellow soldiers!

Five days after the invasion began, the Americans took the highest mountain of the island, Mount Suribachi. Ted watched with pride as the American flag was raised. His commander, Colonel Chandler W. Johnson, led the troops in a celebration of sorts and then decided he wanted a larger flag that could be seen by all the troops. Ted was assigned to go to the beach and find a battle flag from one of the ships. He secured the flag and gave it to a private to take to the top of the mountain. It was raised as Joe Rosenthal, a photographer and newspaperman locked that image into eternity. That picture became one of the most famous photographs of the war and was replicated for the Marine Corps statue in Washington DC. Unfortunately, shortly after the flag was raised, an artillery shell hit the command post and Colonel Johnson took a direct hit. All that could be identified of his remains was his Annapolis ring received at graduation from the Naval Academy. Had Ted personally delivered the flag, he might have been in the command post at that time. That terrible day was March 2, 1945, Ted’s birthday.

The complete securing of the island took thirty-six days, during which the troops were in constant danger. He remembers, “We slept from sheer exhaustion, and ate when we could.” He was involved in much that happened, including the capture of the first prisoners. “Although my life was almost constantly in danger, due to the close contact with the enemy, I never once was injured by enemy action—Many times I had ‘close calls,’ but it seems that I was watched over and protected by a power higher than my own.”[22] During the siege he was taken off the island for three days while suffering from dysentery. After the island was secured, the army took over and the marines were sent to Hawaii. Before leaving, he gathered the surviving Latter-day Saint soldiers to the cemetery, where he had identified the graves of those members killed, and they held a special memorial service for their fallen brothers. He later sent letters to the families of those young men whose bodies remained on the island. He left Iwo Jima on March 26.

In Hawaii, Ted began training almost immediately for what was thought to be the invasion of Japan. Meetings of Latter-day Saint soldiers continued with him as leader. They were blessed with the visit of Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles at one of their meetings. Plans were changed with the end of the war in Europe and the dropping of the atomic bomb on two Japanese cities. On August 14, Japan surrendered. The 5th Division was then assigned to be part of the first occupational forces of Japan, and Ted was assigned as the transportation quartermaster officer for the battalion.[23] He was in charge of loading and unloading the ship. He also had the chance to interact with several Japanese political leaders, including the mayor of Fukuoka. On one occasion he was invited to speak to a prominent political organization in the city on the topic “Democracy and the Reconstruction of Japan.” An observant occupier, he learned much of Japanese culture and customs. His most enjoyable experience in Japan came, however, from his service as a group leader in the Church: “I have more happiness from this work than any other thing I have done since joining the Marine Corps; . . . no service, no matter how good, can give the joy that comes from Church service.”[24]

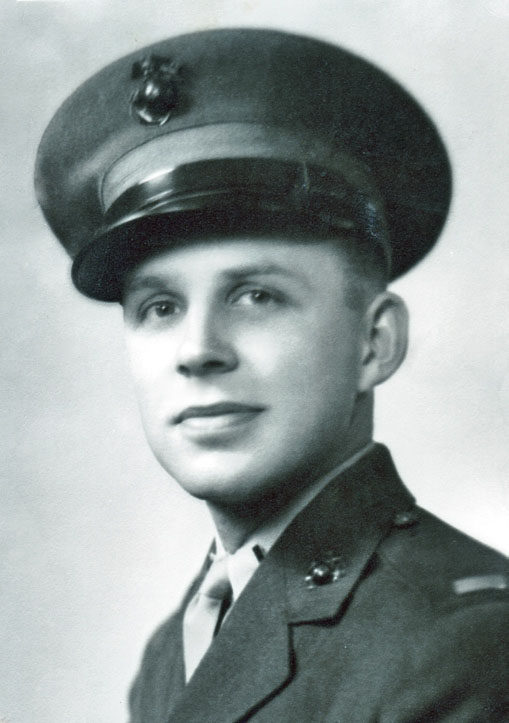

Ted in uniform.

Ted in uniform.

During part of this period of separation, Marné lived part of the time in Manti with Ted’s parents. Their first child, David, was born in December 1944. Ted returned to the United States on December 31, 1945, and was discharged a month later on January 25, 1946. Marné came to California alone to be with him until he was discharged. Then they drove to Utah, where he saw for the first time his thirteen-month-old son, David. Marné’s description is illustrative: “I will always remember the look my two men gave each other—incredulity on Ted’s part to realize he was a father and bewilderment on Davy’s face to see the picture he had called ‘Daddy’ come to life.”

What effects did his war experience have? There were the obvious positive experiences related to his administrative responsibilities where he learned how to be a leader and get things done. There were also the terrible experiences of viewing death and destruction that had to be overcome and dealt with emotionally. Ted did not talk much about the war after coming home, and Marné noticed only one thing that seemed to be the result of war: “My husband reacted strangely whenever David would cry, clutching his back and exclaiming over the pain that struck him intensely.”[25] The loud, high-pitched sound apparently touched a nerve. But probably the most important lessons learned had to do with his faith. He had become a leader with a strong testimony, and wherever he went he gathered members of the Church together, whether active or not. He counseled and helped friends through difficult times. He studied and prayed. “That was one thing that kept our sanity in the process. We could get together and teach the gospel, read the scriptures, bear testimony, and pray. We had a lot more believers on our ship going back than we did coming out.”[26] His influence was described by his close friend and companion in the military, George Stoddard: “Wherever Ted went he left his mark. He was not a neutral person. He never compromised his standards, principles, or actions. His scriptures were always open on a box by his bunk, and did not gather dust. Everyone knew he was a Mormon and that he was in charge.”[27]

Seminary and Institutes

Ted wasted little time trying to get a job. He immediately went to Salt Lake City and talked to Dr. Franklin D. West, administrator of the Church seminary system, letting him know he was ready and anxious to begin teaching. West’s reply: “This is January 26th. We do not hire teachers in the middle of the winter!” Disappointed, he began looking for other work. Two weeks later, however, J. Carl Wood of the seminaries drove from Salt Lake City to Manti to offer Ted a job teaching seminary at Midway High School in Menan, Idaho. He gladly accepted and then unsuccessfully tried to find Menan on a map. Within a week he and his little family were in the small farming community eight miles west of Rigby, between Idaho Falls and Rexburg. Placed into the classroom so quickly, he barely had time to prepare. His first week he wore his marine uniform and told war stories.

Ted quickly realized he had made the right decision regarding his profession. He loved teaching. He enjoyed being in front of students, had few disciplinary problems, and enjoyed working with young people. He was particularly impressed with the type of students he taught. “They didn’t always know how to study, but they knew how to work. They grew up learning how to work. And I learned a tremendous amount from these youngsters.”[28]

One thing that did not impress him was the salary. It was barely enough to pay for the necessities of life. Early on, Marné received a gift of butter, which she wanted to use for baking. “We can’t buy flour now, which will curtail my intention to do a lot of baking. Shortening is also a thing to be wished for. Still we can’t complain, as we are far from starving.”[29] They devised different ways to make additional cash, including raising laying hens. After two years they accepted a position teaching seminary in Brigham City, Utah, which included an increase in salary.

Ted recognized the importance of additional education, so during the second full summer in Idaho he drove his family to Washington state to the home of his in-laws, where he left Marné and their two children, having had their daughter Diane in Idaho. He then drove to northern California, where he had been accepted into a master’s program in educational administration at Stanford University. For three subsequent summers, they did the same thing until he received his degree in 1949, writing a thesis on the released-time program of the seminary system. This pattern of being separated as a family that first occurred because of the military experience became part of their lives as his work, education, and Church service sometimes kept him away from home.

His position in Brigham City was seminary teaching at Box Elder High School. They lived in a nice home of an older couple who were on a mission in Hawaii. They enjoyed Brigham City, in part, because they became close friends with Boyd and Donna Packer, whose lives from that time forward were to be intertwined. In Boyd, Ted found a friend in whom he could have complete confidence and trust. They spent many hours discussing the gospel, teaching, and the future. Neither realized what lay ahead for them regarding Church service.

During the spring of 1950, they went through the same experience of deciding what to do for the summer. Ted and Marné thought about building a home in Brigham City with the hope they would be able to stay in the area. But Ted wanted to go back to school and get his PhD. He enjoyed working with Dr. John C. Almack at Stanford University but was not comfortable with the direction the department appeared to be heading. He decided to apply at the University of Utah, where it would be easier to attend. In May he was offered a part-time seminary teaching position at Davis High in Salt Lake City so he could attend the university. By June of 1950 they left Brigham City and moved to Salt Lake City.

After a year in school during which both Ted and Marné were required to work extra hours to meet their financial obligations, they faced another important decision. Sterling W. Sill, later a General Authority, contacted Ted and offered him a position as an insurance salesman with New York Life Insurance Company. The offer was significantly higher than he would ever receive teaching seminary. They decided to accept the offer, told Sill, and began the process to leave teaching. But peace did not come. “Then we went through great turmoil and couldn’t sleep or find peace even through prayer. So we decided not to do it, and we were at peace with that decision.”[30] Sill was upset and suggested they would later regret their decision. Ted had also been offered the school principalship at Menan and had turned down more money to stay with the Church Educational System. They returned to their life of trying to make ends meet by working double jobs, but they were happy, believing they had made the correct decision. What they did accept was an assignment in 1952 to be director of the institute of religion at the University of Nevada at Reno, which they held for one year. It was a position Ted thoroughly enjoyed.

In 1953 a reorganization of the entire Church Educational System occurred, and Ernest L. Wilkinson, president of Brigham Young University, was put in charge of the Church’s educational programs, and William E. Berrett was asked to administer the seminary and institute program. On August 24, 1953, Ted was in Salt Lake for an interview with a General Authority, “portending great changes in our lives.” He was asked to be a supervisor of Church seminaries and institutes under the supervision of Berrett. Later his friend Boyd K. Packer joined him as a supervisor. Once again they were moving and leaving new friends they had learned to love in Nevada. Marné stated, “I didn’t think we could become so attached to a place, people, and situation in nine short months.” They decided to move to Nephi, where Marné could manage a motel with the goal of making enough money for a home. They were together mostly on the weekends as Ted was traveling, visiting seminaries, or working on his doctorate at the University of Utah. It was not easy for them. But for Marné it was a particularly intense learning experience as she had to manage a motel, care for five children, and look after her two fifteen-year-old twin brothers who were there to help. After being with Ted at a conference where he gave a talk, Marné stated in her diary, “I’m so proud of him and love him dearly. Wish I had the opportunity of getting used to having him around more!”[31]

The next four years were busy as they moved from Nephi to Provo, bought land in Mapleton, sold it, and purchased land and a house in Pleasant Grove. Ted was on the road a lot, supervising and teaching. During this time Marné went through a difficult experience. On March 30, 1957, she began early labor for her fifth child while Ted was in Wyoming and unable to get back in time. She put the children to bed and drove herself to the hospital, writing, “As I drove alone, tears began to flow and I said to myself, ‘This isn’t the way it is suppose to be!’” Circumstances beyond their control had left her alone at that difficult time. But her feelings were soon soothed with the birth of Jonathan Whitaker. “I want to have as many more of these precious spirits as the Lord will allow.” They were to have two more children.[32]

First Council of Seventy

Then came the unexpected call that would significantly change their lives. On March 10, 1958, Oscar A. Kirkham passed away and left a vacancy in the First Council of Seventy. In his diary just a few months earlier, Ted predicted that his traveling companion and friend Boyd K. Packer would be called as a General Authority sometime. “I want to put this down in writing: Boyd will someday be one of the General Authorities. . . . I would put his ‘call’ within the next five years.”[33] But he also had a feeling about himself: “I had some kind of an inkling that something might occur with respect to me.” But that thought was quickly put out of his mind. Then on Saturday of general conference, while interviewing seminary teacher candidates, he received a call from President McKay’s secretary for an afternoon interview in which the call was extended to him to become a member of the First Council of Seventy. His response was that he was not worthy. President McKay’s response: “Well, the Lord knows what He’s doing.”[34]

Returning home, he was in shock. When he came into the house, Marné immediately saw that he was upset. In her diary she described the following:

As I put my arms around my husband, I felt his whole body trembling. I knew some great calamity had just occurred. Like a flash, pictures rose before me of a tragic accident that he must have just witnessed, or that a loved one must have died suddenly. “What can it be?” I questioned him. We sat on the couch in our little frame home, he, with his head on my shoulder, sobbing uncontrollably. Finally he said, “Marné, I have just had an interview with President McKay.” Could he have lost his job? I wondered. Then he said, “I have been asked to be one of the First Council of the Seventy, filling the vacancy left by the death of Brother Oscar A. Kirkham!” No, surely it can’t be so! We are not ready, nor worthy, too soon and too quick! My thoughts, repeated over again.[35]

Diane, their oldest daughter, vividly remembers that night: “I noticed that there was something very secretive going on between Mom and Dad, which had never happened before, but there were tears and pregnant pauses. Then we all gathered together and we had a very emotional prayer, Dad and Mom could barely get through it, they sat us down and told us that he’d been called.”[36]

The next day, Sunday, in the afternoon session of general conference his name was presented. They continued the struggle as Marné stated:

Never before in my life have I felt the full impact of my sins of commission, omission, procrastinations, missed opportunities, slothfulness, and my inabilities and human and spiritual weaknesses so keenly. Nor have I been so humbled; yet so proud of my sweet husband, Ted. Over and over we have repeated in unison, and alone—too soon and too quick; we are not prepared for so awe-inspiring and tremendous a responsibility to serve in the capacity of one of Thy servants along with the great and inspirational souls in Thy Church here on earth.[37]

The more than six thousand in attendance at conference raised their right hands in support of thirty-nine-year-old A. Theodore Tuttle to join a very select group of men with the responsibility of testifying of Christ and administering the work of the Lord on the earth. In his brief speech that afternoon, a visibly shaken Elder Tuttle promised, “I pledge my life to the Lord in his cause and to your service, reserving only sufficient time and means to rear my children honorably before him and before my fellowmen.”[38]

Elder Tuttle as a General Authority.

Elder Tuttle as a General Authority.

Complete and total dedication to whatever the Lord had in mind for him was what Elder Tuttle promised. At that moment there was not even a hint that the direction the Lord had in mind for him would soon be to South America, where he would work in a language he did not know and a culture he had never experienced.

Notes

[1] A. Theodore Tuttle, missionary diary, April 2, 1960; in Marné Tuttle’s possession. Elder Tuttle wrote only occasionally in this diary. During his time as a General Authority, he kept a small calendar diary in which he kept a record of daily occurrences with occasional comments.

[2] Tuttle, missionary diary, June 6, 1960.

[3] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1977, transcript, 15, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1977, 15.

[5] No other General Authority of this period lived farther away from Salt Lake City than did Elder Tuttle.

[6] Most of the information on his early life comes from a document written by Elder Tuttle in 1945 entitled A. Theodore Tuttle, Life; in Marné Tuttle’s possession. This document was written while Tuttle was in Japan with the occupation forces. See also A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Gary L. Shumway and Gordon Irving, 1972–77, transcript, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[7] Marné Whitaker Tuttle, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, 2000, transcript, 45; in author’s possession.

[8] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 3–4.

[9] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 4, 6–7.

[10] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 30.

[11] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 34.

[12] A. Theodore Tuttle, “Developing Faith,” Ensign, November 1986, 72.

[13] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 38.

[14] Information on the early life of Marné was taken from Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” in Marné Tuttle’s possession. The history is a combination of copying of original documents such as letters and diaries and her personal comments. I use this source for her story and comments.

[15] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 6–8.

[16] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 11–14.

[17] Dorothy O. Rea, “Marné Whitaker Tuttle: Adjustments Are Only As Easy as You Make Them,” Church News, November 14, 1964, 6.

[18] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 17.

[19] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 17–22.

[20] Most of the information for this time in Tuttle’s life comes from a small autobiography entitled A. Theodore Tuttle, Life, written in Japan while still in the army. He also wrote a brief history of his experiences at Iwo Jima entitled Memories of Iwo Jima, 1945. The originals are in Marné Tuttle’s possession. Detailed descriptions of his experiences are found in letters written to Marné, two of which were published in Robert C. Freeman and Dennis A. Wright, comp., Saints at War: Experiences of Latter-day Saints in World War II (American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications, 2001), 401–4.

[21] A. Theodore Tuttle, Memories of Iwo Jima, 2.

[22] A. Theodore Tuttle, Memories of Iwo Jima, 5.

[23] For a history of the unit, see Howard M. Conner, The Spearhead: The World War II History of the 5th Marine Division (Washington DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1950).

[24] A. Theodore Tuttle to Dr. E. Earl Pardoe, November 23, 1945; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[25] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 25–26.

[26] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 62.

[27] George Stoddard to Marné Tuttle, April 19, 1987; in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[28] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 69.

[29] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 71.

[30] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 36.

[31] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 46, 49.

[32] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 97.

[33] A. Theodore Tuttle, missionary diary, March 8, 1958.

[34] A. Theodore Tuttle, oral interview, 1972–77, 132–33.

[35] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 101.

[36] Diane Tuttle Hoopes, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, 2001, Santiago, Chile, transcript, 1; in author’s possession.

[37] Marné Tuttle, “Tuttle Family History,” 100.

[38] A. Theodore Tuttle, in Conference Report, April 1958, 121.