Chile: Teaching the Future

Mark L. Grover, "Chile: Teaching the Future," in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 286–311.

The first Churchwide mission presidents’ conference ever held was both exhilarating and troublesome. It was exhilarating because of the Spirit felt and the information received. It was June 1961, and all the mission presidents of the Church were in attendance. They were being instructed by the First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and other General Authorities. It was troublesome, however, because they were concerned they would not be able to do all that was expected. A. Delbert Palmer had just been called as president to serve with his wife, Mable, over a new mission in Chile and had been invited to attend the conference a couple of months before they were to leave. They were the only ones in attendance who did not have experience in the field and were therefore nervous and excited.

Palmer’s attendance at the conference gave Palmer the chance to meet with the other mission presidents serving in South America. Hearing of the successes and failures of Presidents Bangerter, Snelgrove, Fyans, and Sharp was reassuring. Visiting with President Sharp, who presided over the Andes Mission, was enlightening. Talking to Elder Tuttle, who was taking over as president of the South American missions, was invigorating. President and Sister Palmer began to realize they were going to South America at a special time in the history of the Church when growth and development were going to occur. They looked forward to the experience of working with missionaries and members, and they were excited about the possibility of the Church developing in a way that was not anticipated when President Palmer was a missionary in Argentina some twenty years earlier.

President and Sister Palmer.

But then something unexpected happened. This challenge would shape the Palmers’ experience in Chile and the rest of their lives. Shortly after the mission presidents’ conference, they met with the First Presidency on June 26, 1961, to be set apart, though they would not be in Chile until the end of September. In that meeting President Henry D. Moyle suggested that in addition to supervising the proselyting missionaries and member organizations, they should look for ways the Church could help the country in general. President Moyle had already been thinking of how that could be done and suggested they focus on the possibility of organizing Church-operated schools. He asked the Palmers to stop in Mexico on their way to Chile and spend some time with Dan Taylor, who headed the Church schools in Mexico, and see how the schools were operating. President Moyle’s idea was that the Church would begin the school system in one country of South America, and, if successful, schools could then be opened in other countries where the need was great. Although this suggestion was also given to the other mission presidents, President Moyle believed the first schools in South America should be in Chile.[1]

President and Sister Palmer were shocked. They were already concerned about all that would be required to organize and administer a new mission. Now they were being asked to look into organizing a school system that would be the prototype for the rest of South America. They were concerned. Neither of them was an educator, and they had limited understanding of how a school should run and function. President Palmer was not a teacher but a businessman whose company made heating systems for large buildings, such as schools. But they were willing to trust in the Lord and do what was asked. They visited Mexico and saw schools that had been functioning for several years under the direction of the Church. In the end, schools were opened in Chile that not only had full certification from the Chilean government but also the respect and admiration of nonmember Chileans for many years. President and Sister Palmer left an important legacy in Chile.

A Brief History

There is something special about Chile. People feel it when they enter the country. Perhaps it is the incredible beauty of a nation that extends some three thousand miles down the Pacific coast, much of which is a valley, with the ocean on one side and the majestic Andes on the other. Perhaps it is the beauty of that valley, which produces an amazing array of fruits and vegetables with a quality and sweetness seldom equaled. For most visitors, however, the feeling comes from the people, this population of primarily southern European immigrants who mixed with the indigenous population to give the Chileans a subtle beauty. Many Chileans have struggled with poverty and challenges but have done so with a sense of pride and goodness that makes them pleasant and kind.

Their political and economic history has been one of constant tension. Though Chile was not a place of importance in the Spanish American empire because it did not have much gold or silver, the people who settled the region developed a sense of pride and independence that has continued to the present. When independence from Spain finally came in 1817 under the direction of Bernardo O’Higgins, and with the help of troops from Argentina under the direction of José Francisco de San Martín, the country went through minimal social change. The controlling elite of the country did not want a social revolution; they wanted political freedom, which they got. The constitution of 1822 gave token recognition to the ideas of liberty and freedom while incorporating strong provisions to protect the rights of the few elites who were controlling the destiny of the country. The economic and social results of this protection endured, and the country was dominated by a small group of elites who controlled the land and wealth while the majority of the country was destined to poverty. Conservative governments also made sure the Catholic Church maintained its position and role as the symbol of spirituality in the country. This designation restricted and hampered the advancement of Protestant religions for many years.[2]

Political stability was maintained with only occasional clashes between opposing groups. One such conflict occurred in 1851, at the very time Elder Parley P. Pratt was in Chile attempting to establish The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was not until the 1920s, when more liberal groups gained power, that a republican form of government was established and a new constitution accepted. This constitution limited the role of the Catholic Church, and religious freedom became a reality in Chile.

During much of the twentieth century, Chile had an active leftist political tradition. Though not strictly communist, it espoused socialist ideas and called for radical changes in land ownership and social structure. Though these ideas never gained the acceptance of a majority of the population, they found support among the struggling poor of the big cities and the landless peasants of the country. This political movement was a factor in the elections from the 1930s and finally came to power in 1970 with the election of Salvador Allende. The socialist movement was a concern for Church leaders as they established the Church in Chile.

Even though the first attempt to introduce the Church in Chile was in 1851, the actual establishment occurred over one hundred years later, after missions had already been opened in four other countries of South America. Before this time, limited missionary work was done by two different groups. First, American members of the Church, who were transferred to the country to work for American companies or the U.S. government, would talk about the Church to friends and colleagues. Second, because of visa problems, American missionaries were occasionally required to leave Argentina to renew their visas, sometimes every three months. That was accomplished primarily by going to Uruguay, but for missionaries who lived in the western part of the country, such as the city of Mendoza, going to Chile was more logical. Missionaries would cross over into Chile, spend a day in a frontier border town, do some contacting and talk about the Church to people they met, and return to Argentina with a visa valid for the next three months. No known converts resulted from the activities of the Americans or the missionaries.[3]

One more substantial, though in the end unsuccessful, activity deserves noting. In the Argentine fall of 1950, Elders Robert E. Wells and Newell K. Judkins were working in the small western Argentine town of Trevelin. This area of Argentina, nestled up against the Andes, is a beautiful and majestic region that attracted a number of Welsh colonists who settled this cold, mountainous region, growing grains and raising sheep. The missionaries’ work did not convert many of the Welsh, so the missionaries worked with some of the Spanish-speaking population. It was a rural area, and the missionaries’ mode of transportation was horses. The missionary dress consisted of cowboy boots, leather gaucho pants, white shirts, and ties![4]

A copy of the Book of Mormon found its way across the nearby border and into the hands of a schoolteacher in the Chilean logging town of Futaleufú. When he sent word that he and a number of his friends wanted to visit with the missionaries and that the missionaries could stay with him as long as needed, the elders were interested. Permission was granted by the mission president, and Elders Wells and Judkins prepared to go. It was not an easy trip. They went by horseback through a river valley of the Andes, which was rough and required occasional fording of rivers and streams. It was a two-day journey through one of the most beautiful regions in South America. Elder Wells described the trip this way: “We traveled through very beautiful country full of wild geese, birds, small game, trout in the streams, etc. The mountains were snow capped, but down in the gap the weather was fine.”[5]

They arrived at their destination in the afternoon of the second day and studied the town. The buildings were all made of wood. In fact, a few years earlier a forest fire had burned the entire town and the residents were able to escape death only by swimming into the middle of the nearby lake. The missionaries contacted the schoolteacher, and a meeting was scheduled for that evening. Children were sent through the small village to invite all who were interested.

Attending the meeting were six women, a few children, and twelve lumberjacks. The surprised missionaries preached their message to a group that seemed to be interested in what they were saying. The next day they visited the homes of those who had come and then held another meeting in the evening. This time eighteen men attended along with ten women and some children. The missionaries were pleased: “Never in our missionary life in Argentina had we seen more men than women in any meeting. It usually was all women, and zero men. So here all of a sudden we had more Bible reading men in a meeting than I had ever seen in any unit in Argentina, except for a district conference. We were thrilled. We were just tremendously impressed.”[6]

The missionaries left the next day to return to Argentina with visions of numerous baptisms and a strong group of priesthood holders in a soon to be organized branch. However, it was not to be. Their request to return to Chile was not granted. Instead the mission president assigned two other missionaries permanently to the city. A series of problems hampered their work. They had health problems, which affected their enthusiasm. They feared additional illness, and when a storm completely isolated them from the surrounding towns and thus medical help, they panicked and requested permission to return to Argentina after having been in the village only two months. No branch was organized and no Church presence established, though one young man was eventually baptized. But Wells realized there was potential for the Church in Chile. He suggested, “The people of Chile that we had met were more spiritually inclined than the Argentines and the Welsh and that the men were definitely more ready for the priesthood should they join the Church.”[7]

Church Established

A few years later, plans were made for missionaries to permanently go to Chile. To ensure order in the expansion of the Church in South America, the First Presidency in 1955 wrote to President Lee Valentine of the Argentine Mission indicating that Chile had been added to their mission but missionaries were not to be sent to the country yet. At about the same time Peru was added to the Uruguayan Mission.[8]

President Valentine began to get ready. In Santiago, Billie Fotheringham was working for Eastman Kodak Company and had moved with his family to Chile. He wrote letters to Church headquarters in Salt Lake City urging that missionaries be brought into the country. Correspondence from President McKay encouraged him to have two missionaries get the proper papers to go to Chile but to wait for permission. By May the following year, when President Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency came for a visit, they were ready. Valentine explained to President Moyle all he had done, after which on May 30, 1956, President Moyle wrote a letter to President McKay suggesting the time was right to send missionaries into Chile: “President Valentine has two missionaries ready to go to Santiago if desired. . . . I understand I was empowered to organize a branch in Santiago if I felt it was the right time but I had no instructions as to sending missionaries there. . . . Elders Allred and Bentley have their papers and visas ready to go to Chile when directed. This was already done before my arrival on the strength of your direct correspondence with the mission.”[9]

Permission was received, and on June 14, 1956, Elders Verle Allred and Joseph Bentley were notified of their transfer to Chile. They arrived in Santiago on June 23 and were met at the airport by Fotheringham. Bentley’s feelings were sobering: “I’m a little scared and know that—or I should say we—are going to need the help of the Lord like we never have before. I feel very deeply the responsibility placed upon me and it humbles me.”[10] They settled into an apartment and prepared for the visit of President Moyle, whom they met at the airport on July 2. President Moyle shared his feelings about the work, saying, “It is clear to me we have a great future in Chile.” Then he asked the missionaries to go to work: “At my request they went tracting all day, in the morning in a moderately well to do area and in the afternoon in a wealthier section. They had six cottage meetings in each and a gospel conversation in the seventh. . . . They fasted all day and were thrilled with the results. They reported the city better than any Argentine city they were ever in.”[11] The neighborhood of the city where they worked turned out to be a wise choice. They selected the area by pointing a finger at the map. The chosen neighborhood was two blocks from the home of Ricardo García and his family, the first converts baptized in Chile.

President Moyle was confident about what could happen in Chile: “Never in all my experience have I felt the power of the Priesthood more in me than when I told them that I knew that the Lord had sent me here for some purpose, not revealed to me yet. So I know that a divine assignment rest upon me. I told them we were ushering in in South America a new era in which the Church will go forward much faster than ever before in South America.”[12]

On July 5, President Moyle set apart Brother Fotheringham as the branch president in the first branch in Chile. In President Moyle’s prayer, he asked that the blessings Elder Ballard gave to South America in 1925 be brought to Chile. Then President Moyle predicted that it would be a mission someday, that there would be strong members, and that there would be at least ten branches in the mission. Bentley was dubious: “It was hard for us to believe at that time. He said it wouldn’t be too far off.”[13]

After securing a place for Church meetings and living quarters, the elders began serious missionary work. The first sacrament meeting had close to seventy people in attendance. They asked for more missionaries to help. President Valentine left South America in September, and his replacement, Lorin Pace, sent two more missionaries in October. Pace was impressed with Chile: “To the degree it was possible we gave great emphasis to Chile. We tried to see that we sent capable and able missionaries to Chile. We wanted to make sure that our commitment to Chile was a successful commitment.” He had reasons for increasing the commitment to the country. By his calculations, a missionary worked 480 hours for each convert in Argentina. The missionaries in Chile worked 128 hours per convert.[14] The first baptisms were held on November 25, 1956, when nine were baptized: the García family, the Saldano family, and three members of the Lanzarotti family. By May 1959, there were three branches organized, twenty-one members, and ten missionaries. Two pieces of property for chapels were purchased in Santiago and one in Concepción.[15]

Administration of the mission was not easy. It was a long way from Buenos Aires, and the mission president was not able to be in Chile as much as he desired. President Pace tried to visit once every six weeks, but that was not enough. The missionaries felt alone and isolated and needed more direction. Elder Spencer W. Kimball of the Quorum of the Twelve visited in 1959 and saw firsthand the difficulty in being so far from the mission president. He recognized a need for a change and suggested to the First Presidency that a new mission be organized.

Andes Mission

The organization of the mission occurred that year and coincided with the visit of Elder Harold B. Lee’s tour of the South American missions. In July 1959, James Vernon Sharp and his wife, Fawn, were called by President Moyle to preside over a new mission that included Chile and Peru. They hadn’t decided on a name or a headquarters. The name being suggested was the Chile/

Sharp was well aware of the history of struggles with government officials in both Mexico and Argentina and wanted to avoid political conflicts as much as possible. He felt they needed to go slow in introducing the Church. It was important that the Church be recognized in each country as a separate identity not connected to the other country. Then if there were political problems, the mission in either country could function completely independent of the other. The separate office in Santiago was important for the Church to be recognized in the country. President Sharp spent considerable time in each country ensuring the separation of the two parts of the mission.

On his way to South America, Sharp stopped in Washington DC and visited the consul offices of both countries. In the Chilean embassy, he was informed that “you’ve got to have a political friend in order to get what you need in Chile.” Sharp was aware of no one who could help him. The consul then noticed his tie clasp, which was from the Utah Society of Professional Engineers. The conversation continued with the consul indicating that his brother was trying to get into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), without success. Sharp, who had contacts at the university, asked to use the telephone and within half an hour had information that the brother not only had been accepted but could in fact register for classes. That small incident created a valuable friend for the Church. With the help of the consul, the Church was recognized and allowed to function as a religious organization without paying taxes.[17]

The Sharps left the United States and went to Peru. On October 21, 1958, they went to Chile to get ready for the meeting to organize the new mission. On October 30, they placed the flags of the two countries in front of the audience, and Elder Harold B. Lee organized the Andes Mission. He explained the concept of the two mission homes and stated that the headquarters would be in Lima. When a vote of acceptance was requested, several refused to support the decision. Elder Lee then took time to explain why the decision had been made but experienced little success convincing the Chilean members.[18] The political history between the two countries was contentious and would continue to hinder the Church as long as the two countries remained in one mission.

They remained together in one mission for two years. It was not easy. The Sharps were centered in Lima and would spend three weeks in Peru. Then for three weeks they would go to Chile and work with the missionaries and members. It was hard on them not to have just one home. Their supervision was needed in both places all the time. Sister Sharp observed, “We seem to be disappointed when we arrive in Santiago. Even when these conferences are planned and set up months ahead, when we arrived, nothing has been done by way of preparation.” The weeks spent in Chile would have its consequences in Lima. “On returning to Lima, we were greatly disappointed in our missionaries that were living in the home.”[19]

On May 18 a devastating earthquake hit Concepcíon, Chile, and destroyed four hundred homes, killed two hundred people, and damaged the chapel. President Sharp was in Lima but immediately went to the American consulate to offer the services of the missionaries as translators. He got to Chile as soon as possible and went to the minister of foreign affairs with an offer of further help. The foreign minister stated, “You know, I had a feeling you were going to come. We have been reading a bit about you Mormon folks and how in times of need, you help.”[20] They needed blankets, warm clothing, and medicine. The Church provided two thousand blankets and six thousand pounds of clothing and was the first international relief organization to get to the area. President Palmer stated, “The Church’s contribution to Chile of both tangible aid and missionary translators was long remembered by Chilean government officials and the general populace.”[21]

Chilean Mission

In December 1960 the visit of President Joseph Fielding Smith and Elder Tuttle to Chile was important. It was a memorable visit in part because of a couple of mishaps. Elder Tuttle had to leave partway through the visit to take over the Central American Mission because of a seriously ill mission president. Also Sister Jessie Evans Smith had fallen and broken her hand. It was an important visit because it resulted in the recommendation for two separate missions. President Smith was impressed with Chile. While looking at a piece of property the Church was considering for a chapel in Viña del Mar, he predicted, “You should buy more land because I see someday that there will be a temple built here.” Additional land was purchased, and on the property the Church built a chapel and a school. In his report to the First Presidency, after discussing the problems of distance and communication, President Smith recommended the mission be split.[22]

Organizing the new mission was Elder Tuttle’s responsibility. Coming to Chile was the first trip Sister Tuttle made outside of Uruguay, and she enjoyed it. She brought along their five-month-old, blond-haired son Boyd, who was nursing at the time. On the flight into Santiago, she described the view of the Andes, the rivers, and the northern desert areas from the plane: “As we crossed the great desert we could see the snow peaks of the Andes in the distance. Interesting to see silver streaks of rivers cutting down towards the sea with patches of green all along it—sandy and dry rocky land come right to the edge crowding the fertile land that lay along the river valleys.” She described her first meal in Chile of artichokes on a skew of brazed beef tongue, fish, bacon wrapped around a prune, and shrimp as “very tasty.” She then commented on the changing of the guard at the park of the Presidential Palace (La Casa de Moneda): “Watched change of guard in the plaza (below our window) in front of the Royal Palace. A fine band played while Ted and I danced to a few bars of the Nat’l anthem in our room. First dancing in a long time.” She described another view from her room: “As I look out on the square through the hotel window I see a feather duster salesman talking to the taxi men trying to sell them his wares. They look like a pom pom on a stick. People seem to spend a lot of time dusting off their autos.” Then she noted something with which she was not too familiar: “Stationed along this end of the Plaza I count eighteen uniformed policemen plus a truck load and a tank manned by at least six police. The other end of the Plaza is the presidential place, and the police are here for precautionary measures, I presume.”[23] The tense situation was due to political conflicts between the ruling party and the political leftists.

The Tuttles then went to Lima for the organization of the Peru Mission, which occurred on October 1. The mission included all of Peru, the northern city of Arica, Chile, and the country of Bolivia, which did not have missionaries until 1966. Then on October 8, a meeting was held in a room next to El Golf theater to organize the new Chile Mission, the sixty-fourth mission of the Church. The room was filled with 445 people, and most of the missionaries had to stand. Elder Tuttle expressed his beliefs in the future of the mission: “A great future awaited the Church in Chile and that it was a special land whose people had a special spirit and feeling about them.”[24] The membership totaled 1,148 people who were organized into twelve branches in three districts.[25] With the new mission, Chile was primed to experience growth and development unequaled in South America.

President and Sister Palmer were then left alone to administer the mission. The Palmers were descendants from pioneer families who had been asked to leave Utah and colonize in Canada. President Palmer’s father had immigrated to Canada to raise sugar beets. He became involved in other activities, including working as a school principal and finally as an assistant superintendent of a government-sponsored experimental farm in Lethbridge, Alberta, where Delbert was raised. He served as stake president in Lethbridge for more than twenty years. Delbert attended the local schools and then went to Utah State University for two and a half years, where he majored in business administration. He then returned home to work to save money for his mission. While getting ready to go, he met Mable Johansen, who had also been raised in Canada. She was working as a secretary, having studied business for two years at Brigham Young University. She waited more than two years for Delbert to return from his mission to Argentina, and they were married on July 30, 1941, within a week of his arrival home, anticipating he would immediately be called into military service. The call did not materialize, and they both worked in Calgary before moving to Lethbridge. He was part owner of a propane-distributing business until 1952 and then started a business in 1954, manufacturing and distributing specialized heating equipment for schools.

The call to preside over a mission was not a complete surprise. Several years earlier, in 1952, Elder John A. Widtsoe of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had asked the Palmers about going to Argentina to take the place of President Harold Brown. At the time Mable was pregnant and seriously struggling with her health. After a day, Elder Widtsoe returned and told them it was not yet their time to go on a mission. But he suggested a future call: “I feel that you will have an opportunity later on.”[26]

Establishing the Mission

President Moyle’s admonition to organize a school system was on the Palmers’ mind, but the realization of that goal came later. They had a mission to establish and a Church organization to run. It was not an easy task. The challenge of establishing a new mission was significant. The struggles of the first few months were many, and the Palmers felt they were being hampered on every side. They had sixty-five missionaries and 1,148 members. There were twelve branches in three different areas, Santiago, Concepción, and Valparaiso/

A large part of the challenge related to the logistics of setting up the mission. The Palmers did not have a car nor a telephone in the mission office. They lived a half mile from the office, which meant they walked and used public transportation. The Chilean bureaucratic requirements for establishing the Church in the country were significant. Palmer stated, “It just takes forever to get anything done.”[28]

One of their first goals was to get the missionaries to learn the new lesson plans introduced Churchwide earlier in the summer. For some it was a simple task, but for many it was a challenge. It took time and patience. A more immediate problem was illness. There were so many missionaries with hepatitis that they had to convert the entire third floor of the mission offices into an infirmary. The health of the missionaries improved with the introduction of gamma globulin shots given every three months.

Political instability was a great concern. Chile had a history of democracy, which allowed for political involvement from a wide spectrum of society. During this period, a particularly dynamic political movement came from the left. Several socialist parties were active in attempting to gain power, which they eventually did in 1970 with the election of Salvador Allende. While the Palmers were in Chile, these movements fueled significant anti-American activity, which often focused on the American Latter-day Saint missionaries. The Church was a frequent target of articles in socialist and communist newspapers attacking the Church. The missionaries were almost always seen as agents of the American spy agency, the CIA. Palmer felt that the level and number of attacks on the Church were hindering the success of missionary work.[29]

Cultural shock, combined with all that had to be done to establish the mission, took its toll on the Palmers, particularly in the first month. But time helped improve the situation and their attitudes. This change is beautifully described in Mable’s letter to her family at the end of October 1961: “On many of the main streets there is a loverly [sic] plazas in the middle of the street with flowers and shrubs growing in them. When we first arrived our hearts were a little heavy, and when we drove down the streets I noticed mostly the ugly mud fences, but it is funny the way I don’t see the fences anymore, only the rose bushes peeping over them.”[30]

It was with these concerns and worries that the Palmers attended a meeting for the South American mission presidents in December 1961 in Montevideo, Uruguay. Discussions with the other mission presidents showed they were having similar experiences. Something was hampering their work. All the presidents and their wives gathered at the Tuttles’ home for a testimony meeting that included a special prayer by Elder Tuttle. Sister Palmer described the experience: “He [Tuttle] mentioned how he felt the powers of evil and darkness over all this land and how it had been prophesied that the gospel of Jesus Christ would save this country. He said, ‘The hope of this country is in this room.’ In his prayer he called down the blessings of heaven upon us and the mission until there was not a dry eye in the room.”[31]

President Palmer suggested this experience was one of the most significant of his mission. From that time forth, things changed: “The feeling that we all experienced was that of the removal of a dark, heavy cloud which had been hovering over us to reveal a beautiful, bright, sunlit sky.”[32]

Establishing the Schools

The pressure of the work left little time for the Palmers to think about establishing a Church school system. But events in 1962 began activities in that direction. President Palmer was not an educator but a businessman who believed in education. The experience he had of observing a Church school in Mexico on the way to Chile left him with an appreciation of such schools in the evolution of the Church: “There was a spirit of unbounded enthusiasm and excitement among both the students and the teachers. Member children, who would otherwise have remained illiterate or semi-illiterate, were now learning. It seemed as though we could actually see future missionaries, bishops, Relief Society presidents, staring at us from the bright-eyed eager faces of those descendants of Lehi.”[33]

Elder Tuttle was an educator and from the beginning of his time in South America looked forward to the time when Church schools could be organized there. He believed the introduction of schools would be crucial in strengthening the Church in Latin America, writing, “I’m sure from this humble beginning schools will spread all over this great South American continent doing more good than anyone thing except the preaching of the gospel itself.”[34]

Early on, Elder Tuttle believed Chile was the place to establish the first schools in South America. During his first visit to Chile to open the mission, he spent the day of October 6, 1961, investigating the establishment of schools.[35] He continued to think of the schools but was involved in other activities that distracted him. During a visit to Chile in 1962, both he and President Palmer visited with a Mr. Strossner of the Department of Education to ascertain the feelings of the government concerning the possibility of Church schools. Strossner expressed hope that the Church would establish the schools and promised help getting permission from the Chilean congress to allow duty-free importation of educational material. This visit was followed with a visit to the deputy minister of education, Mr. Onate.[36] In February 1963, when Elder Tuttle was again in Chile, he was approached by a representative from the Cisterna Branch who “said they represented a group of parents from their district and had come to ask the Church to do what it could to establish schools for their children.”[37] Elder Tuttle was moved by the requests for help from these members.

That same month, President Palmer and Elder Tuttle had a long talk with Hugh B. Brown about the possibility of schools in Chile. President Brown was enthusiastic and told them to submit a recommendation to the First Presidency. For the first time since he had arrived in South America, Elder Tuttle felt the time was right for the schools to be organized and began working on a proposal to send to Salt Lake City. In April he sent a letter to all the South American mission presidents beginning with this hopeful statement: “We continue to receive bits of hope that sometime—perhaps in the near future—we might be able to have schools in South America.” In the letter, Elder Tuttle asked each president to make recommendations for schools in their missions. He was specific in how the schools would be organized, indicating the size of the classes and availability of teachers. He asked for the number of children who might attend the schools and the physical facilities that would be available.[38]

President Palmer’s detailed response to Elder Tuttle contained a large number of arguments supporting a need for a school. Chile was an underdeveloped nation, especially in the area of education. The strength of the leftist political parties could result in further disintegration of the nation, including the school system. The number of Chileans actually attending school beyond the sixth grade was less than 30 percent. Palmer believed, however, the need for Church schools was based less on the failure of education in the country than on the specific needs of Church members. Most member children had access to schools, but they were required to attend state-sponsored religious classes taught by Catholic priests: “In some instances, where our children have been attending Catholic schools they have been subjected to persecution.”[39]

President Palmer suggested the reason for the schools was directly related to the evolution of the Church. He believed the schools would “do more to establish Zion in this country than any other factor.” The religious and moral characteristics of the schools would prepare young members not only to obtain good jobs but also to become leaders in the Church: “The incorporation of moral teachings into daily instruction can help them prepare to form an LDS home.” Palmer then mapped out where the schools would be established, made suggestions on administration, and finally indicated the cost of the project. It was a detailed and thorough report demonstrating that the Chilean Mission was anxious and waiting for the chance to start the pilot program.[40]

As impressive as Palmer’s report may have been, an additional factor was probably more influential in persuading Elder Tuttle that Chile was the place to start the schools. In July 1962, Dale Harding, an educator who had been working at Brigham Young University and had a master’s degree in education, received a Fulbright fellowship to go to Chile and work in a school. His interests were in training and curriculum. He and his wife, Joyce, had adopted two Chilean children, adding to their family of four children, and were interested in staying in the country. Here was the right administrator to start the schools. He had a background in Church education, an interest in developing curriculum, and a year’s experience teaching in Chilean schools. But they had to move quickly because Harding’s fellowship ended in July, and he would be returning to the United States.[41]

President Palmer sent his proposal to President Brown. Elder Tuttle included a letter officially requesting the establishment of Church schools. Elder Tuttle supported Palmer’s reasons for the schools, which included persecution Church members were receiving in public schools along with the idea that schools would train future Church leaders. Elder Tuttle added a third reason related to the Church’s responsibility to the indigenous population: “to fulfill the promises of the Lord as recorded in the Book of Mormon concerning the discharge of our full obligations to his Lamanite children.”[42] President Brown quickly responded to Palmer with tentative approval: “The Brethren are very much interested in the possibility of establishing a school or schools, not only in Chile but other South American countries. It is our opinion that sort of a test or pilot project could be instigated there in Chile, and I think you will have the complete approval of the First Presidency in any program that can be established before the opening of the next school year. . . . I think a green light can be given for immediate action.”[43]

President Palmer was authorized to talk to Harding and begin negotiating a stay in Chile to establish the school under the direction of President Palmer. Harding accepted the position, along with a living allowance, a furnished home, and travel expenses. Final approval was given on June 11, 1963, and was announced in the Church weekly magazine on June 29.[44]

Thus began an adventure that would last ten years. An elected parent group was to have an integral role in the school. Most teachers were to be both Chilean and Church members, but two teachers would be sister missionaries from the United States. All students would be required to pay a nominal monthly fee. The school would also receive some financial assistance from the Church. Dale Harding wrote the curriculum, which was based on Chilean educational requirements, Church principles, and the development of creativity.[45]

The First Presidency authorized two different schools, the first in Santiago at the chapel in La Cisterna (David O. McKay School) and a second in the coastal town of Viña del Mar (Hugh B. Brown School). A board of education was made up of the presidents of the branches involved in the school. A special plan was presented to the ministry of education and approved. Finally an agreement was made with the government allowing educational materials from the United States to be imported. The program was named Asociación Educacional y Cultural de La Iglesia de Jesucristo de Los Santos de los Ultimos Días (Educational and Cultural Association of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

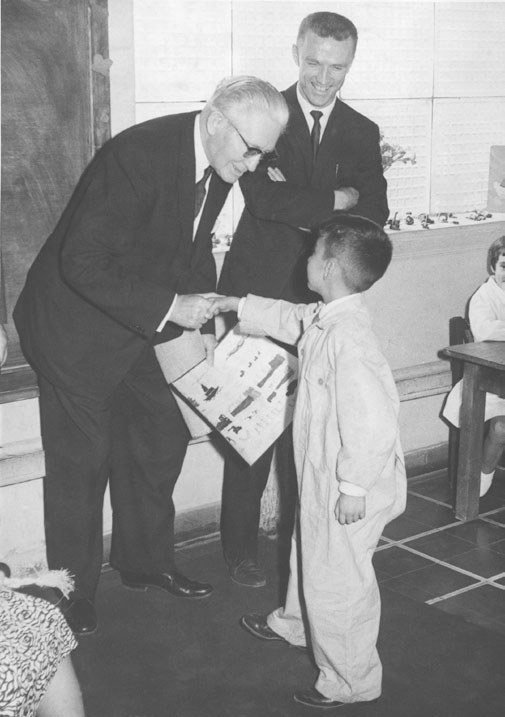

As plans were being finalized to open the schools in March 1964, the Palmers were released a few months earlier than expected. Carl and Helen Beecroft, who had been presiding over a mission in Mexico, experienced visa problems and were required to leave Mexico. They were assigned to Chile and officiated over the opening of the schools and the first few years of the schools’ existence. By March 1964, the two schools were opened with 173 total students enrolled. The schools received some notoriety, and admittance was competitive. Members of other faiths attempted to get into the schools, one mother even offering to be baptized on the spot. Another tried to convince the director she was a member of the Church but was exposed when she was unable to identify Joseph Smith. Children of members had to be turned away because of lack of space. The quality of the teaching was evident at the end of the school year when all students in the two schools passed the government administered year-end examinations, a rare occurrence for any school in Chile. Elder Tuttle related to the First Presidency, “The Church Schools have been visited and acclaimed by many friends of the Church, educators, and other important people in Chile.”[46]

President Hugh B. Brown meets Chilean school student with Dale Harding.

Under Dale Harding’s direction, the schools grew in both size and quality. When school began in 1964, they expanded to another chapel in Santiago, with a total of 339 students, twelve salaried Chilean teachers, and two sister missionary teachers.[47] One of the greatest honors for President Palmer occurred in 1965, when the Church opened a second school in Santiago (Republica) and named it the “A. Delbert Palmer School.” This was a fitting honor for the president who worked hard to ensure that the dream of schools became a reality. The success of the schools so impressed President Brown that he planned similar schools first in Peru and then in all the countries of South America. But those expansion plans never materialized.[48] In Chile the program expanded into seven different regions, including Arica in the far north. The number attending reached more than 2,600 students. However, in 1978 the Church announced closure of the schools as part of the closing of most Church schools worldwide. One reason cited was the availablity of adequate schools in the country. A second reason that was probably closer to reality was the cost of the schools made it impossible for the Church to provide educational opportunities to all its members either in Chile or worldwide. Elder Tuttle’s and President Palmer’s dream of Church schools throughout South America would not become a reality.[49]

Conclusion

The opening of schools in Chile is probably the best example of Elder Tuttle’s goal for the Church in South America. He saw the Church’s evolution in South America as mirroring what was happening in the United States. Elder Tuttle believed members in South America deserved the privilege of attending Church schools, and his primary efforts were to this effect. Just as in Mexico, where members had Church schools in which the secular was taught under the influence of the Spirit, so did the members in South America deserve that privilege. Just as the Polynesians and Americans had colleges and universities where religion was taught alongside science and art, so would they be taught to the members in South America. But it was an expensive and costly dream that would not materialize in the way they had hoped. It would be through the seminary and institute programs that the dreams of religious instruction in South America would occur.

Notes

[1] For a description of the conversation, see A. Delbert Palmer, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1973, 25, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Most of the personal information about the Palmers comes from this interview and the autobiography of Mable entitled Mable Johansen Palmer: My Life’s Adventure (privately published, 1998).

[2] Brian Loveman, Chile: The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 119, 124, 219. For a study of the evolution of the Chilean constitution, see Pablo Rolando Cristoffanini, Dominación y legitimidad politica en Hispanoamérica (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 1991).

[3] A. Delbert Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1979), 60.

[4] Robert E. Wells, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, February 2001, Santiago, Chile; copy in author’s possession.

[5] Wells, oral interview, February 2001.

[6] Robert E. Wells to A. Delbert Palmer, May 4, 1973; copy in author’s possession.

[7] Wells to Palmer, May 4, 1973.

[8] First Presidency to President Lee Valentine, May 26, 1955. A typed copy of the letter is in “Manuscript History of the Argentine Mission,” May 26, 1955.

[9] Henry D. Moyle to President David O. McKay, June 1956; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[10] Joseph Bentley to Barbara Hart, June 21, 1956, as quoted in A. Delbert Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 74.

[11] Henry Dinwoodey Moyle Journal, July 3, 1956, Church History Library.

[12] Notes by Amy Valentine at a meeting with missionaries in Mendoza, Argentina, July 4, 1956; copy in author’s possession.

[13] Joseph Bentley, oral interview, interview by A. Delbert Palmer, January 20, 1979, Salt Lake City; copy in author’s possession. See also Moyle Journal, July 5, 1956.

[14] Loren Pace, oral interview, interview by A. Delbert Palmer, December 1978, as quoted in A. Delbert Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 79–80.

[15] H. Dyke Walton, “Building Activity in South America: 1 July 1965”; copy in author’s possession.

[16] James Vernon Sharp, oral interview, interview by Gordon Irving, 1972, 43, Church History Library.

[17] Sharp, oral Interview, 46.

[18] Fawn Hansen Sharp, Life History of Fawn Hansen Sharp (n.p., n.d.), 68–69, Church History Library.

[19] Fawn Hansen Sharp, Life History, January 19, 1961, and February 22–26, 1961. At this part of her autobiography, she includes parts of her mission diary. Instead of pages, dates are used.

[20] Sharp, oral interview, 57.

[21] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 92.

[22] Sharp, oral interview, 62.

[23] Marné Tuttle, diary, October 3, 5–6, 1961.

[24] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 104.

[25] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 105–6.

[26] Palmer, oral interview, 22.

[27] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 106.

[28] A. Delbert Palmer to family, October, 1961; copy in author’s possession.

[29] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 120–22.

[30] Mable Palmer to family, October 30, 1961; copy in author’s possession.

[31] Mable Palmer to family, December 17, 1961; copy in author’s possession.

[32] Palmer, “Establishing the LDS Church in Chile,” 117.

[33] Palmer, “Church Schools in Chile: Why and How,” unpublished paper, Brigham Young University, 1977, 6; copy in author’s possession.

[34] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” June 17, 1963.

[35] “Manuscript History of the South American Mission,” October 6, 1961.

[36] “Manuscript History of the Chilean Mission,” Church History Library; see also Palmer, “Church Schools in Chile: Why and How,” 9.

[37] Untitled paper in A. Delbert Palmer’s files describing events related to schools; copy in author’s possession.

[38] A. Theodore Tuttle to mission presidents, April 13, 1963; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[39] Palmer, “Church Schools in Chile,” 2.

[40] Palmer, “Church Schools in Chile,” 3.

[41] Dale Harding, oral interview, interview by Mark L. Grover, February 6, 2001, Sandy, Utah. There were also additional members from the United States who were involved in the planning of the school: Wendell Hall, Director of the Chilean North American Cultural Institute in Valparaíso, and John M. Bailey, working for the United States AID program in Santiago.

[42] A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, May 28, 1963; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[43] Hugh B. Brown to A. Delbert Palmer, May 17, 1963; A. Theodore Tuttle to the First Presidency, May 17, 1963; copies in Marné Tuttle’s possession.

[44] First Presidency to A. Theodore Tuttle, June 11, 1963; copies in Marné Tuttle’s possession; “Church to Open Schools in Chile,” Church News, June 29, 1963, 3.

[45] Dale Harding, “Schools in Chile: Suggestions,” March 7, 1963; copy in author’s possession. See also Harding, oral interview. Copies of curriculum outline and specific programs are in author’s possession.

[46] Elder Tuttle to the First Presidency, 25–26. No date was on the letter, but because of its content it was determined to have been written in 1965. Notice this statement in a letter from Elder Tuttle to Delbert Palmer, December 13, 1964, regarding the fact that all the students passed the test: “While this may not be unusual in the United States, it was so phenomenal that the inspectors could not believe it. Never do all of the students in a school pass the examination! As a result of this, the inspectors stayed at the school for three hours trying to ascertain whether the examinations were valid, or if they could have possibly made any mistake” (copies in author’s possession).

[47] Tuttle to the First Presidency, 27.

[48] A. Thomas and Helen Fyans to the Tuttles, September 19, 1964; copy in Marné Tuttle’s possession. At that time President David O. McKay was struggling with serious health problems, and many such proposals were not acted upon.

[49] Benigno Pantoja Arratia, “Mi Experiencia vivida en los Colegios de la Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos de los Ultimos Dias en Chile,” n.d., 192–93, Church History Library. This is an extensive description of the schools during the time Pantoja was director of the schools from 1974 to 1978. Lyle J. Loosle became director after Harding left in 1967 and continued in this position until 1973.