Temple Hill, New Technology, and a Second Temple—1980 to 1999

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Temple Hill, New Technology, and a Second Temple—1980 to 1999," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 351–378.

The 1998 announcement of a temple in Kona, Hawai‘i (the second temple in what was then the 42nd most populous US state), was clearly a compliment to the Saints in Hawai‘i. Above photo of Laie Hawaii Temple by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii. Photo of Kona Hawaii Temple courtesy of Denise Bird, birdinparadise.com.

The 1998 announcement of a temple in Kona, Hawai‘i (the second temple in what was then the 42nd most populous US state), was clearly a compliment to the Saints in Hawai‘i. Above photo of Laie Hawaii Temple by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii. Photo of Kona Hawaii Temple courtesy of Denise Bird, birdinparadise.com.

With the advent of so many temples in the Asia-Pacific region, and given the Church’s nearly complete standardization of practices among temples worldwide, the Hawaii Temple’s years as a “pioneer temple” in which it extended blessings into new countries, provided ordinance work in new languages, accommodated foreign excursions, and so on seemed to have passed. Yet in the 1980s and 1990s the temple continued to experience dynamic changes that arose within its own sphere as well as Church-initiated changes that would come to temples across the world.

Visitors’ Center Renovation

In 1979–80 the main visitors’ center, located on the north side of the temple plaza, underwent extensive renovation. At construction’s end, its exterior looked much as it did before, yet the interior had been significantly enlarged and filled with new displays and presentations.

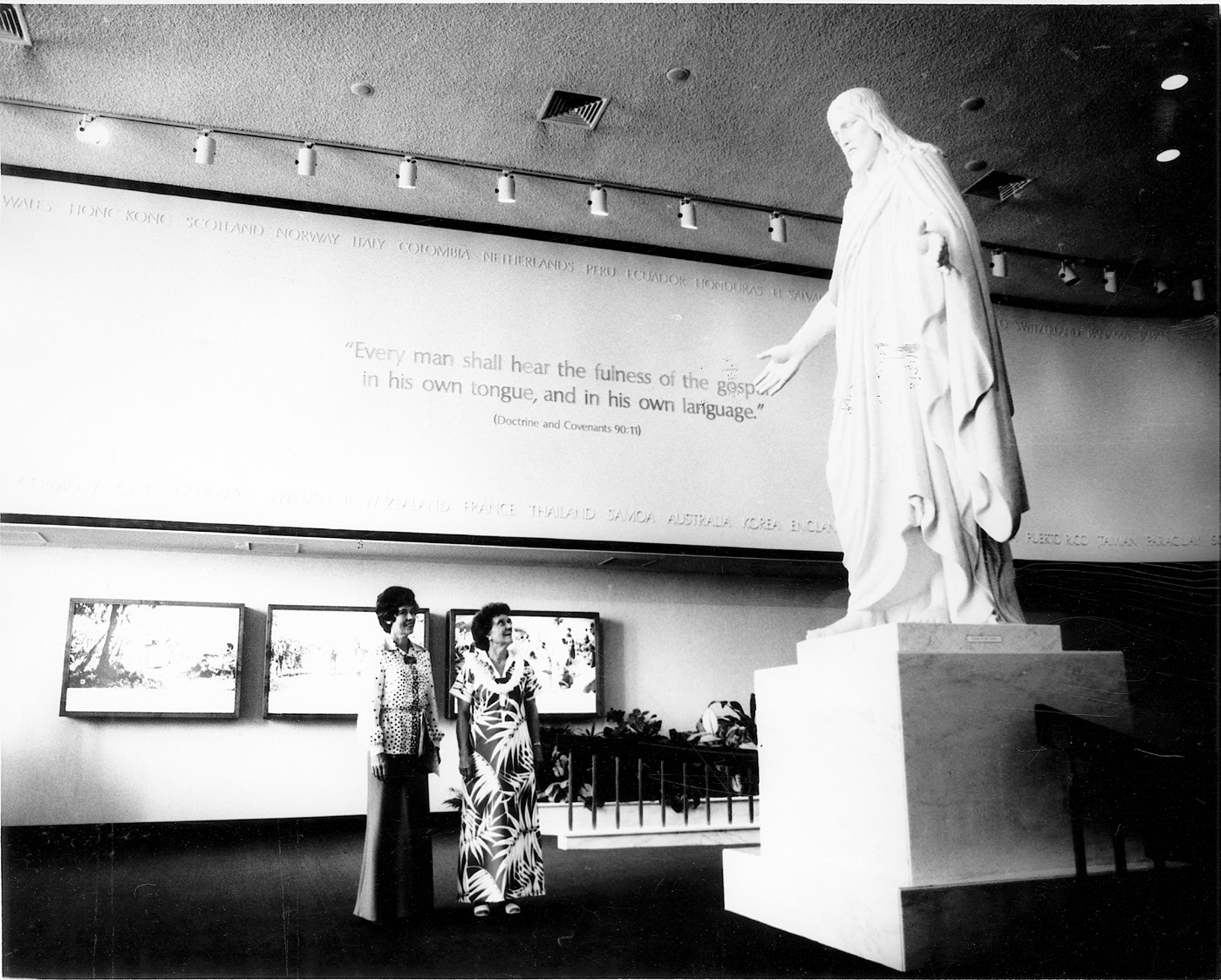

The large reception area included several informational Translight displays, some specially produced to show Polynesian cultural and historic connections with the gospel. A large-scale model of the Lāʻie area (including the temple, BYU–Hawaii campus, and Polynesian Cultural Center) occupied a mid-area toward the back of the foyer. But dominating the center of the new space was an eight-foot-tall Carrara marble statue of Jesus Christ similar to those displayed in the Salt Lake and Los Angeles Temple visitors’ centers at that time. Placed on a square, three-tier pedestal about four feet high, the statue—a copy of the original Christus sculpted by Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen in the nineteenth century—inspired reverential awe in members and nonmember visitors alike. Additionally, as one newspaper article noted, the “statue of Jesus Christ should dispel any visiting non-LDS doubts about whether or not Mormons follow the Savior.”[1]

The 1979–80 expansion of the Hawaii Temple’s main visitors’ center included the addition of a Christus statue. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The 1979–80 expansion of the Hawaii Temple’s main visitors’ center included the addition of a Christus statue. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Three instructional rooms opened from the foyer. One room (known as the temple theater) shared the importance of temples using a film and a 36-inch-high scale model of Solomon’s temple; another room employed a “talking” mannequin of the Nephite prophet-warrior Mormon and a movie to explain the Book of Mormon. The third room (the mirror theater) taught the value of the individual within a family and the opportunity that temples afford families to be united for eternity.[2]

The renovated visitors’ center was rededicated on 6 December 1980 by Elder Adney Y. Komatsu. Among those who spoke at the service, temple president Max W. Moody drew a connection between the visitors’ center and the temple: “In this building, people first hear about the Gospel. . . . Up there in the building on the hill, the highest ordinances in the Church and on this earth are consummated. It’s a vast difference; here is the very beginning of Mormonism to the visitor, up there is the ultimate to the church member who has done everything that he can do to prepare himself for the highest ordinance of them all.”[3]

Other Developments in the Early 1980s

The 1982 temple schedule included thirty-four sessions a week compared to twenty before the 1976–78 remodel—a 70 percent increase.[4] After four and a half years of service, the Moodys were released and on 29 August 1982 Robert H. and Betty T. Finlayson were set apart as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple by Gordon B. Hinckley, who was then serving as a third counselor to President Kimball. The change involved a gathering at the George Q. Cannon Activities Center (BYU–Hawaii campus). In his remarks President Finlayson welcomed the opportunity to serve and marveled at the changes in his life since he converted to the restored gospel nearly twenty-five years earlier at age forty-six. “When I walked in that first church meeting, I knew I was home,” he said.[5]

Also in the early 1980s, a number of “military temple retreats” were organized. There were nearly a dozen military bases across the state (including at least one base for each branch of the military), and Latter-day Saint chaplains arranged these two-day retreats for active-duty Church members in an effort to rejuvenate their faith. Several servicemen in these groups later said that as a result of the experience they had “become regular temple goers.”[6]

In another development, the former Japanese visitors’ center located across the plaza from the main visitors’ center became the new location for the genealogical library (now the Laie Hawaii Family History Center) that was previously located in the BYU–Hawaii library. This transfer to the Hawaii Temple visitors’ center plaza linked with the opening of the Family History Library in 1985 in Salt Lake City—the largest genealogical library in the world.[7]

Recommends for Unendowed Spouses

A few months after Ezra Taft Benson became President of the Church in November 1985, the First Presidency announced that “a person who is married to an unendowed spouse may receive a recommend” conditional on the spouse’s consent and assurance that doing so “will not impair marital harmony.”[8] This was welcome news to many Church members like Ida Otake. Ida had married an inactive Church member and was later baptized in 1967. She recalled, “As I learned more about the Church and the purpose of the temple, my desire to enter the temple increased.”[9] Yet without her husband, this was not possible at that time.

Ida was among the sisters who helped clean the temple preparatory to its rededication in 1978 and cherished the feelings of reverence and joy she had felt there. In 1981 her younger sister, also a Church member, invited Ida to be baptized for her mother. “I was excited to know that I could actually do this. It was the most spiritual, uplifting feeling I had ever had. I could feel my mother’s presence.” Yet her husband remained inactive. Finally able to attend the temple for her own ordinances after the 1986 announcement, Ida said, “It was joyous. My youngest sister, Laura, was my escort, and many of my dear friends were in attendance as well. I felt that again my mother was present during this session.” Her husband never went to the temple, but one year after his death, Ida arranged for completion of his saving ordinances: “My husband and I were sealed, with my oldest son serving as proxy. . . . He has the same name as my husband. He later shared that he could feel his dad’s presence throughout the sealing. Then each of our children that were there were sealed to us.”[10]

Priesthood-Only Sessions Discontinued

In 1986 a new Church policy directed that temple presidents would serve three-year fixed terms, just as mission presidents did. As a result, the Finlaysons were released and D. Arthur Haycock, a former missionary (1935–37) and mission president (1954–58) in Hawaiʻi, and his wife Maurine were set apart as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple in June of that year.[11]

Not long into the Haycocks’ service, the First Presidency announced the discontinuation of designated priesthood sessions in temples. In an interview, President Haycock explained that a balance of men and women performing ordinances was no longer required. And noting that women had sometimes waited in the foyer while their spouses attended these male-only sessions, he welcomed the new directive.[12] Temple work proceeded steadily during the Haycocks’ tenure, but this was not all. During his career employment at Church headquarters, President Haycock had served as secretary to five prophets (George Albert Smith, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, Spencer W. Kimball, and Ezra Taft Benson).[13] President Haycock used his considerable experience to bring about numerous improvements to the temple and the surrounding grounds.

Improvements to the Temple and Its Grounds

Early in his tenure, President Haycock made numerous observations of the temple and its surroundings. He noticed several graves of early Hawaiian pioneer members in the nearly impenetrable foliage on the hill behind the temple and also discovered Avard Fairbanks’s statue Lehi Blessing Joseph in back of the temple nearly overgrown by shrubbery and in need of repair. He could see the historic friezes around the top of the temple by the same artist that, after nearly seventy years of exposure to the elements, were also showing significant signs of wear. Ultimately President Haycock made a thorough review of the temple grounds and its interior, identifying numerous improvements, and work began almost immediately.[14]

Friezes restored

The request for repair of the friezes was submitted to Church headquarters in early 1987, and Justin Fairbanks, son of Avard Fairbanks, was tasked with the job. Upon close observation, the damage was much more extensive than originally thought. Arms, legs, and even heads of some of the statues in the friezes had succumbed to the pressure of steel rebar expanding as it rusted.[15] Fairbanks and his assistant Ballard T. White worked with a crew of craftsmen, mostly students at BYU–Hawaii, to first remove the multiple layers of old paint. “The work was meticulous and tedious, but the reward was the uncovering of a veiled masterpiece.”[16]

Removing layers of old paint during the 1987 restoration of the friezes, the craftsmen uncovered “a veiled masterpiece.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Removing layers of old paint during the 1987 restoration of the friezes, the craftsmen uncovered “a veiled masterpiece.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

As paint was removed, additional cracks in the friezes were uncovered and in some cases pieces of the sculptures came off. The rusted part of the rebar was cut away, and the remaining exposed rebar was coated with rust-resistant paint. Then the cut-out portions, cracks, and damaged areas were filled with a grout mixture. Each frieze was painted with two coats of white acrylic paint, and the sculptures were highlighted to give a greater sense of depth.[17]

In addition to the friezes, Justin Fairbanks and his crew also restored the Maternity statue at the head of the cascading pools and the heroic-size Lehi Blessing Joseph statue. All sculpture work was completed by early August 1987.

Temple grounds

A flurry of improvements were made to the temple in 1988. The first phase focused on the temple grounds and began in March in order to be finished before the peak crowds of summer visitors arrived. This work included retiling all the plaza areas and walks and retiling the large reflecting pool in the center with blue tile. New marble was placed on all the building columns, and the east courtyard (opposite the visitors’ center) was tiled and refurbished to provide a new setting for the renovated sculpture Lehi Blessing Joseph as well as for model copies of the four friezes on top of the temple, which were displayed along the back wall.[18]

Temple interior

Among several improvements made to the temple grounds in 1988, the sculpture Lehi Blessing Joseph and replicas of the four friezes were added to the courtyard opposite the main visitors’ center. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Among several improvements made to the temple grounds in 1988, the sculpture Lehi Blessing Joseph and replicas of the four friezes were added to the courtyard opposite the main visitors’ center. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The second phase of renovation mainly involved the temple’s interior and coincided with the temple’s annual summer closure in August. These improvements included a new elevator, a new lobby and entrance, a new bride’s room, and a refurbished celestial room and ordinance rooms. The seventy-year-old louvered windows, commonly used in the islands to maximize air flow, were replaced with pane windows.[19] Although the original plan was to reopen the temple in November, the extensive renovations delayed the reopening until January 1989.

President Haycock had seen an elegant crystal table with a tropical design at the O. C. Tanner jewelry store in Salt Lake City while visiting for general conference. He considered it a perfect centerpiece for the Hawaii Temple’s celestial room. President Hinckley said, “It’s beautiful but . . . we can’t give you any money, but I know you’ll get it.” After returning to the islands, an affluent member approached President Haycock, saying that the celestial room felt empty and he thought a table was needed in it. Arrangements were then made for the table to be shipped to the islands and installed.[20]

Of what was done in 1988, President Haycock explained, “The improvements made in both the grounds and Temple are in harmony with His Spirit which we invite to be there. We’ve only done what always should be done to honor and recognize Him.”[21]

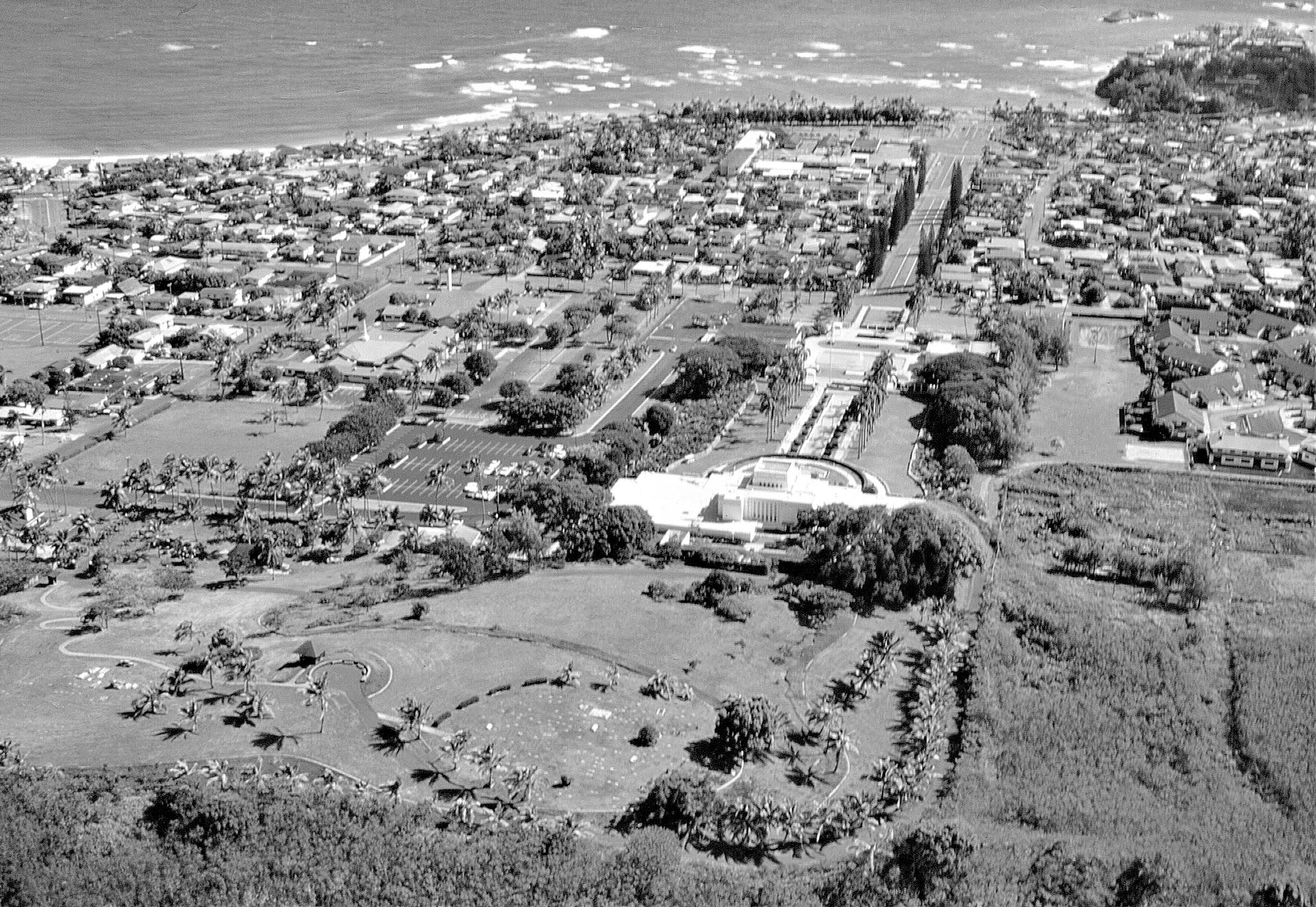

Temple Hill

Perhaps the most noticeable changes concerned the area directly behind the temple commonly known as “Temple Hill.” Like several local members, President Haycock was aware of an old cemetery on this hill that once adjoined the I Hemolele Chapel, which for many years stood on the same ground on which the temple was later constructed. At the time of the temple’s original construction, a new cemetery was opened a half mile away on the northern edge of Lāʻie. Over the next seventy years, the graves behind the temple had become lost in a jungle of growth on the hill along with an assortment of old abandoned cars and huts left by tenant farmers.[22] Among those buried there were pioneer Saints who had helped establish the Church in Hawaiʻi and assisted in making Lāʻie a place of gathering worthy of a temple. In addition to honoring them, Haycock felt that revitalizing Temple Hill would “greatly enhance the beauty and surroundings of the House of the Lord—and add to its security, general welfare, and appearance as well.”[23]

Efforts starting in 1987 to restore the long-overgrown area behind the temple (known as “Temple Hill”) included the restoration of the cemetery where a number of Lāʻie’s pioneers were buried. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Efforts starting in 1987 to restore the long-overgrown area behind the temple (known as “Temple Hill”) included the restoration of the cemetery where a number of Lāʻie’s pioneers were buried. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Although the hill was Church property, Zions Securities (responsible for managing Church-owned land in Lāʻie) informed President Haycock that it lacked the funds to restore the area but approved of any efforts he might make to do so.[24] Thus in March 1987, less than a year into Haycock’s presidency, eighty volunteer students from BYU–Hawaii began clearing the hill in back of the temple of vegetation, rubbish, old cars (including a motorcycle), and several old shacks. A member of the temple grounds crew, Sam Kekauoha, believed his great-grandfather was buried on the hill but had never been able to locate his grave. Most graves discovered were in shambles, but one student came across a coral headstone with markings that she believed to be the name “Kekauaha.” Sam was beckoned, and upon further clearing of the headstone, to Sam’s great joy it became clear that it was indeed his great-grandfather’s grave.[25] Among other contributors was a large group of Tongan Saints from across the island of Oʻahu who, on two separate occasions in November, spent an entire day clearing large portions of the hill.[26]

The assistance of Herbert Kazuo Horita and many others significantly extended the beauty and use of the temple grounds and has properly honored those buried there. Courtesy of Wayne Yoshimura.

The assistance of Herbert Kazuo Horita and many others significantly extended the beauty and use of the temple grounds and has properly honored those buried there. Courtesy of Wayne Yoshimura.

These contributions to clearing the hill were valued, yet the hill took in several acres and progress appeared modest against such a large area. Then in December 1987 President Haycock spoke to the Waipahu Hawaiʻi Stake leaders. As his subject, he spoke of Hawaiian pioneer “Ma” Manuhiʻi, who had cared for the teenage missionary Joseph F. Smith, and lamented that the gravesites of her and other “faithful pioneers” now lay “forgotten, unattended and unhonored.”[27] Upon the meeting’s conclusion, Herbert Kazuo Horita, a successful real estate developer, offered to help, saying, “I want to take care of that cemetery,” and with his team he worked to make sure the project was “first class,” paying all expenses.[28]

In addition to clearing the hill and restoring the cemetery, workers made the portion of the hill just above the temple parking lot into a gathering area. “In the past, many tail-gate meals have been eaten on the parking lot following temple sessions but now an attractive park area centering around a new Samoa Fale (or summer house) is available for Church groups attending the Temple.”[29]

Finally, Herbert Horita gifted the commission of a life-size bronze statue of “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi (1832–1919) just inside the park’s entrance to represent the Hawaiian pioneer spirit that the entire project was meant to honor and preserve. BYU–Hawaii art professor Jan Fisher received the commission, yet without any known photo of Ma at that time, he wrestled with how to sculpt Manuhiʻi in her younger days. Rather than select a model, Fisher sought spiritual direction in the temple and in his personal prayers. Later, he described: “The veil was parted, and a young and lovely Ma Manuhiʻi stood before [me]. As the vision continued, Ma Manuhii knelt and gently lifted the sick and suffering boy Joseph F. Smith. . . . [I] was able to see in exquisite detail her beautiful hands and feet and lovely brown face.” Fisher returned to his studio at BYU–Hawaii and completed his work on the sculpture. When finished, “the beautiful statue was shown to President Haycock, [who] turned to Brother Fisher and commented, ‘She has been here, hasn’t she, Brother Fisher?’ ‘Yes, she has, President. Yes, she has.’”[30]

Continued work on the cemetery

At the conclusion of his presidency in 1989, President Haycock noted that “some of the [elderly] are working on the identification of the graves.”[31] This effort would continue for another five years. With the help of others, Edwin L. Kamauoha, who had experience helping restore the cemetery at Iosepa (Skull Valley, Utah), continued the search for graves. He noted that the graves were seemingly scattered all around because the coral underground made some areas prohibitive for burial (sometimes dynamite had been used to loosen the rock). Of finding the graves, Kamauoha explained that one has to “follow the Spirit when you don’t know where to look for the graves” and that some were identified by imported stone and others by broken glass from vases placed by the graves in years past.[32]

Temple president D. Arthur Haycock and sculptor Jan Fisher next to statue of “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi (1989). Photo courtesy of D. Arthur Haycock family.

Temple president D. Arthur Haycock and sculptor Jan Fisher next to statue of “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi (1989). Photo courtesy of D. Arthur Haycock family.

Joaquin Chang, with Warren Soh and numerous volunteers, continued clearing and preserving the graves. According to Chang, ninety graves have been identified near the temple, and “the earliest recorded burial was 1881. Many others have no dates or names and could have been buried earlier.” Eventually Chang and Soh were able to place 289 headstones.[33] “I felt this work was like a mission to me,” Chang said, “not a Church mission, but a mission to assist the spirits placed here and forgotten. I did this work especially for the community and for the pioneers who are buried here.”[34]

When visitors begin to ascend the hill of the Laie Pioneer Memorial Cemetery, they find a plaque that reads, “Here, in the shadow of the Temple, lie many of our honored Pioneer dead—They who helped establish the true Church in Hawaii and make Laie blossom as the rose.” As one observer of these special grounds aptly stated, “What once was a repository of old, wrecked cars and trash is now a choice place to stroll, to consider the past as well as the present and future.”[35]

Arrival of Computers

Victor B. and Marva T. Jex replaced the Haycocks as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple in 1989, the seventieth year of the temple’s operation. As the Jexes began their service, ordinance work in the Hawaii Temple was still being tracked and recorded on paper, then filed in shoebox-like containers and mailed to Salt Lake City for preservation. That procedure changed with the arrival of a computer ordinance recording system in 1990.[36]

Extending back and to the north of the temple, the park area and Laie Pioneer Memorial Cemetery have greatly added to the use, beauty, and peace of the temple grounds. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Extending back and to the north of the temple, the park area and Laie Pioneer Memorial Cemetery have greatly added to the use, beauty, and peace of the temple grounds. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

For most of the Hawaii Temple’s history, Church policy required that names submitted for vicarious ordinances be identified on family group sheets, submitted by a family representative, checked by the Genealogical Society (or an approved regional location, such as Hawaiʻi for the Asia-Pacific region), and then placed in reserve for family members to perform the work or in a temple file for patrons who had no names of their own. The cumbersome process often created a high percentage of duplicate names and at times resulted in a shortage of names in temples.[37]

In 1977 three Church departments—Temple, Genealogical, and Information Systems—officially began a cooperative effort to develop a computer program that would relieve temples of the heavy paperwork involved in preparing names for ordinance work. The first computer-automated temple recording system went into effect in February 1981 in the Salt Lake Temple. The system considerably reduced the arduous typing, proofreading, checking, filing, and reporting that had taken much of the temple workers’ time; the new system reduced shipping and storage costs as well. Endowment sessions no longer required the services of typists and stake checkers, and the name-by-name proofreading that could last hours was no longer necessary.[38]

By 1986 the system had been implemented in twenty-three of the Church’s forty temples, yet before it was introduced in Hawaiʻi, change in policy and advancement in technology warranted another change. As a result, the first computerized system for the Hawaii Temple did not arrive until 1990. Once in place, the newer system further simplified the work of temple personnel and also integrated TempleReady (another computer program designed to help members clear names for submission themselves). Another advancement was that computer disks were used to send and receive names and completed ordinance work between the Genealogical Department in Salt Lake City (renamed the Family History Department) and the temple.[39]

Alongside the use of computers to organize information and streamline work within temples was the increasing use of computers in gathering names for temple work. The first version of Personal Ancestral File—a program for personal computers with which anyone could compile family group sheets and pedigree charts and prepare names for temple work—was released in 1984. The Genealogical Library was finished in 1985 (renamed the Family History Library in 1987), followed by the appearance of Ancestry.com in 1996 and FamilySearch.org in 1999.[40] The pervasive use of computers in temple work has not come without growing pains, and their use continues to evolve. Yet in the Hawaii Temple, as in all others, computers have come to greatly facilitate the work.

Developments in the 1990s

Over the years, Church members have visited Hawaiʻi for a variety of reasons and while there have made a point to visit the temple. Illustrative of this variety, in 1991 branch leaders arranged for twenty-five young men from the US mainland, who were working in Maui’s pineapple fields for seven months, to fly to Oʻahu to attend the temple. They arrived on 30 March at 9:00 a.m. and were baptized for 625 and confirmed for 750 before returning to Maui that afternoon. A temple worker commented, “The group was very reverent and a wonderful feeling prevailed.”[41]

Marshall Islands Saints

Also in the 1990s, facilitated by direct flights to Honolulu, a series of annual temple trips from the Marshall Islands began. Located more than two thousand miles southwest of Hawaiʻi, the Marshall Islands are made up of two archipelagic island chains of thirty atolls and 1,152 islands, yet comprise only seventy square miles of land. In 1991 thirty Marshallese Saints received their endowments in the Hawaii Temple and did the work for their ancestors; several couples were sealed as well. A temple worker noted that it took this group between two and six years to save enough money for the airfare and that “their humility and faith were observed daily and all the temple workers felt the very special atmosphere that surrounded these members.”[42] These trips continued for a number of years, later resulting in the official inclusion of the Marshall Islands in the Hawaii Temple boundaries.

Albert and Alice Ho, 1992–1995

Marshall Islands Saints (from Ebeye Island) in 2007. Temple trips from the Marshall Islands to the Hawaii Temple began in the early 1990s. Courtesy of David and Shelly Swenson.

Marshall Islands Saints (from Ebeye Island) in 2007. Temple trips from the Marshall Islands to the Hawaii Temple began in the early 1990s. Courtesy of David and Shelly Swenson.

Albert Y. G. Ho and Alice Kihohiro Ho of the Hawaiʻi Kai First Ward replaced the Jexes as temple president and matron in 1992. Their service began on 1 September, just as Hurricane Iniki was approaching the islands. The island of Kauaʻi suffered extensive damage, and Oʻahu felt some of the storm’s effects. Sister Ho reflected on their unusual start: “Power in Laie was lost [and the temple closed] for a few days. . . . That was the beginning.”[43]

The cost and time involved in inter-island travel made it difficult for members from the outer islands to commit to a traditional temple worker schedule. To help address this challenge, outer-island members were increasingly called to serve in the temple as “restricted temple ordinance workers.” These members were trained as ordinance workers but served solely when their ward or stake attended the temple.

The number of restricted ordinance workers increased during the Ho administration from five in 1992 to more than three hundred in 1995 as they began including members from stakes on Oʻahu for special stake or ward sessions and occasionally when regular ordinance workers were not available.[44] One example of these special sessions was “A Day in the Temple”—when ward or stake groups would spend the entire day doing ordinance work. The extra endowment sessions and sealings were generally officiated by the restricted ordinance workers from the ward or stake in attendance that day. A temple worker observed that “A Day in the Temple” events “were very special occasions wherein the Spirit was felt very strong as the patrons dedicated a full day to temple work.”[45]

A new president of BYU–Hawaii, Eric B. Shumway, was inaugurated on 18 November 1994. Hearkening back to earlier administrations, the inauguration committee requested that a special temple session be held on 19 November for school leaders and visiting Church authorities. “We occasionally attended the temple thereafter as a president’s council,” President Shumway recalled, “and felt the temple was extremely important, especially to the campus and our students.”[46]

David and Carolyn Hannemann, 1995–1998

Longtime Lāʻie resident and PCC vice president T. David and Carolyn Hannemann became president and matron of the Hawaii Temple in 1995. A Honolulu newspaper noted, “Hannemann, 71, who is of Samoan-German-English ancestry, is the first Polynesian to head the temple.”[47] During the Hannemanns’ service, the number of scheduled endowment sessions significantly increased. To begin, during the peak hours of Friday evening and Saturday morning, sessions were increased from every hour to every half hour. Moreover, the temple opened on Mondays after a visit from President Gordon B. Hinckley. On return from dedicating the Hong Kong China Temple, President Hinckley made a Monday stop in Hawaiʻi. Sister Hannemann recalled a humorous conversation between President Hinckley and President Hannemann. “Are you open on Monday?” “No,” President Hannemann replied. The prophet quipped, “Well, if you were, I’d be here.” Sister Hannemann added, “He encouraged us to open on Monday, and we did after that.”[48] The temple opened Monday mornings but was closed in the evening for family home evening.[49]

In a nod to the tradition of temple sessions on Thanksgiving Day (discontinued in the early 1970s), the community news bulletin announced: “In commemoration of the dedication of the Hawaii LDS Temple on Thanksgiving Day 1919, President T. David Hannemann has announced continuous Temple Sessions will be held every 40 minutes starting at 7 am on Friday, Nov. 28 through the day and night until the last session—Nov 29.”[50] It was recorded that 1,220 endowments were completed, and a record number of patrons participated.[51] Yet perhaps most effective and lasting was President Hannemann’s inclination to use more BYU–Hawaii students as temple workers. The BYU–Hawaii challenge of “Go Forth to Serve” fixed deeply in President Hannemann’s mind. He felt that if students were trained as temple ordinance workers, then when they returned home to their countries they could immediately contribute to the work in their own temples. President Hannemann called nearly one hundred students as temple workers, and a sizable contingency of student workers has continued serving in the Hawaii Temple ever since.[52]

A Second Temple in Hawaiʻi

At the 1978 rededication of the Laie Hawaii Temple, President Spencer W. Kimball counseled the members to increase their temple attendance and future temples would follow. Then, in the April 1998 general conference, President Gordon B. Hinkley announced that thirty “small, beautiful, serviceable temples” would be built. And one month later, on 7 May, it was officially announced that one of those temples would be built in Kona, on the western side of Hawaiʻi Island, or the “Big Island.”

The volume of temple building announced by President Hinckley had no precedent, and the pattern of “small” serviceable temples (without a laundry, a cafeteria, and waiting rooms and with an average size of 10,700 square feet) was clearly a break from temple designs of the preceding era. Yet his reasoning for taking temples to the people, the minimal design, and the small size were not new. In his announcement President Hinckley reasoned:

Now . . . in recent months we have traveled far out among the membership of the Church. I have been with many who have very little of this world’s goods. But they have in their hearts a great burning faith concerning this latter-day work. . . . They love the Lord and want to do His will. They are paying their tithing, modest as it is. They make tremendous sacrifices to visit the temples. . . . They save their money and do without to make it all possible.

Accordingly, I take this opportunity to announce to the entire Church a program to construct some 30 smaller temples immediately.[53]

And it was eighty-three years earlier that President Joseph F. Smith almost identically reasoned:

Now, away off in the Pacific Ocean are various groups of islands. . . . On them are thousands of good people. . . . When you carry the Gospel to them they receive it with open hearts. They need the same privileges that we do, and that we enjoy, but these are out of their power. They are poor, and they can’t gather means to come up here to be endowed, and sealed . . . for their living and their dead, and to be baptized for their dead. . . . They are a tithe-paying people. . . .

Now . . . we have come to the conclusion that it would be a good thing to build a temple . . . down upon one of the Sandwich Islands.[54]

Similar to the design of the small temples envisioned by President Hinckley, the design of the Hawaii Temple diverged drastically from its predecessors in its minimal design, focusing almost exclusively on the temple’s essential ceremonies and eliminating all nonessential rooms. And as originally constructed (10,500 square feet), the Hawaii Temple remains one of the smallest Latter-day Saint temples ever built.

The reasoning for small temples shared by President Gordon B. Hinckley in 1998 mirrored the reasoning and minimalist design presented over eighty years earlier by President Joseph F. Smith when announcing the Hawaii Temple. Photo of Laie Temple (preceding page) by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii. Photo of Kona Temple (above) courtesy of Aaron Nuffer.

The reasoning for small temples shared by President Gordon B. Hinckley in 1998 mirrored the reasoning and minimalist design presented over eighty years earlier by President Joseph F. Smith when announcing the Hawaii Temple. Photo of Laie Temple (preceding page) by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii. Photo of Kona Temple (above) courtesy of Aaron Nuffer.

A second temple in what was then the forty-second most populous US state was clearly a compliment to the Hawaiian Saints.[55] In a number of ways the honor seemed fitting. For eighty years the Saints on the outer islands had regularly found their way to the temple in Lāʻie by boat, train, plane, bus, and automobile; and they had incurred the additional cost of food, lodging, and lost wages in the process. Then beginning in the 1980s and into the 1990s, leaders in the Hilo and Kona Stakes in the island of Hawaiʻi increasingly brought their members on monthly temple trips to Oʻahu.[56]

In early 1997, while seeking the Lord’s guidance as the newly called Kona Stake president, Philip A. Harris had a dream in which he saw a temple in Kona. With only two stakes on the entire island, he assumed the Lord wanted him to emphasize temple work among his members, and he got to work.

President Harris estimated that it collectively cost members in the Kona Stake approximately $442,000 a year to attend the temple in Lāʻie for one week (considering transportation, lodging, food, and lost wages). He then estimated it would cost only $92,000 a year to attend as a stake one day a month—flying in Saturday morning and returning home that evening. He called his friend, temple president David Hannemann, who gladly agreed to extend the Saturday schedule once a month to accommodate them (with the visiting stake supplying their own ordinance workers). The monthly temple trips began. President Harris encouraged his members to bring a sack lunch and to purchase their own temple clothing. He recalled, “Every time we would arrive I would hold up my briefcase with my temple clothes, and I would say, ‘Brothers and sisters, I’m not waiting in line because I have my own clothes, and it’s time for you to buy your own clothes.’ And so that’s what we did.”[57]

After President Hinckley announced that the Church would build small temples, he invited stake presidents who felt their location might qualify for such a temple to submit a letter. President Harris said that the following week, “I flew to Laie to go to the temple because I wanted to be absolutely sure that when I wrote the letter that would be exactly what Heavenly Father would want me to say. So I came back and wrote the letter, and my two counselors signed. I talked about my dream and shared what it cost us originally to go on temple excursions, and what it costs us now going once a month.”[58] Within weeks the announcement was made that a temple would be built in Kona.

Four months after the Kona Hawaii Temple was announced (7 May 1998), the Hannemanns were released and Elder J. Richard Clarke, emeritus General Authority, and his wife Barbara Jean Reed Clarke began their service as the Hawaii Temple president and matron. Two months later, in November 1998, the Hawaii Temple was officially renamed the Laie Hawaii Temple to avoid confusion with the additional temple in Kona.[59]

Ground was broken for the Kona Hawaii Temple on 13 March 1999, and less than ten months later, on 23 January 2000, the temple was dedicated by President Gordon B. Hinckley. The Kona Hawaii Temple was tenth in a line of more than thirty small temples. It became the Church’s seventieth operating temple and the sixth temple built in the Pacific Islands.

Notes

[1] “Temple Visitor’s Center Rededication Planned,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, November 1980, 1, 6.

[2] “Temple Visitor’s Center Rededication Planned,” 1, 6.

[3] “New Visitor’s Center ‘Is a Building of Beauty—A Fit Structure for the Spirit of the Lord,’” Ke Alakaʻi, 15 December 1980, 17.

[4] “Hawaii Temple Announces 1982 Endowment Schedule,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, October–November 1981, 7.

[5] “Former Stake Patriarch New Temple President—Convert Succeeds Max W. Moody in Position,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, August–September 1982, 1.

[6] “LDS Military Go on 2-Day Temple Retreat,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, May 1985, 15.

[7] That this occurred in 1985 is based on the Joseph F. Smith Library’s audit report for 1984–85, Brigham Young University–Hawaii. Special thanks to Marynelle Chew for providing this information.

[8] First Presidency Letter, “Temple Recommends for Members Married to Unendowed Spouses” (12 February 1986).

[9] Ida Otake, reminiscence, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[10] Otake, reminiscence.

[11] See Gerry Avant, “Secretary to Five Prophets Called as Temple President,” Deseret News, 19 January 1986, 6. See also “Hawaii Temple Has New President,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, August 1986, 1.

[12] See Chris Eslinger, “New Policy Brings Temple Changes,” Ke Alakaʻi, 26 September 1986, 1.

[13] See Avant, “Secretary to Five Prophets Called As Temple President,” 6.

[14] See Norman R. Bowen, “Hawaii Temple Shines like a ‘Pacific Jewel,’” Church News, 21 January 1989, 6, 13. See also “D. Arthur Haycock Power Behind Temple Restoration,” Hawaii LDS News (formerly Hawaii Record Bulletin), January 1989, 1, 4.

[15] See Grant Turner, “Annual Gathering Discusses Historic LDS Hawaii Temple,” Ke Alakaʻi, 25 May 1988, 1. Consideration was given to removing the friezes altogether and preserving them in a museum. Also considered was their replacement with granite copies, but the one-million-dollar price tag was considered excessive (the original temple cost only a quarter million dollars). Ultimately it was determined to restore the friezes in place.

[16] Ballard T. White in consultation with Justin F. Fairbanks, “Restoration of the Hawaii Temple Friezes” (Mormon Pacific Historical Society proceedings, 21 May 1988, conference held at Hawaii Temple Visitors’ Center), 13.

[17] See White, “Restoration of the Hawaii Temple Friezes,” 13–18.

[18] See Norm Bowen, “Summertime Visitors to Temple Will See Major Improvements to Grounds,” Hawaii LDS News, summer issue, 1988, 3. See also Bowen, “Hawaii Temple Shines,” 6, 13.

[19] “Temple Re-Opens after Extensive Remodeling,” Hawaii LDS News, January 1989, 1, 4. See Bowen, “Hawaii Temple Shines,” 6, 13.

[20] Lynette and Brett Dowdle, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 26 May 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Oral History Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL). The Dowdles identify this generous member as Herbert Kazuo Horita.

[21] Quoted in Bowen, “Summertime Visitors to Temple,” 3.

[22] See David Arthur Haycock to William Grant Bangerter, 6 January 1988, CR 335 22, CHL. See also Bowen, “Summertime Visitors to Temple,” 3.

[23] See Haycock to Bangerter, 6 January 1988.

[24] See Haycock to Bangerter, 6 January 1988.

[25] Yearly Temple Reports (Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, 1987).

[26] See Yearly Temple Reports (1987).

[27] Haycock to Bangerter, 11 January 1988. Although President Haycock and others believed “Ma” Manuhi‘i was buried in the cemetery behind the temple, her specific gravesite in Lāʻie is not currently known.

[28] Haycock to Bangerter, 11 January 1988.

[29] Bowen, “Hawaii Temple Shines,” 6, 13. See Bowen, “Summertime Visitors to Temple,” 3. Just over a year into the project a local Church newsletter described the progress this way: “The 200 graves found by the workers are being identified by interested volunteers and relatives of the deceased. Weathered grave markers are being restored and the hill is becoming a delightful park with paths and breath-taking scenic views in all directions. . . . Buried there are converts and LDS who left their homes elsewhere to move to Laie and help make it, first a ‘refuge,’ then a Church-owned plantation, and now a prospering center for Church-sponsored higher education, temple work and tourism in Hawaii” (“Workers Restore Old LDS Cemetery on Temple Hill,” Hawaii LDS News, January 1989, 6).

[30] Erika Ngo, reminiscence, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[31] D. Arthur Haycock, interview 14 April 1989, OH-338, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 17.

[32] “Laie Temple Hill Park: Honoring Our Past,” Hawaii LDS News, 1993, 14.

[33] Joaquin Chang, “Kupuna ‘talk story,’” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa (community newspaper distributed in Lāʻie, Kahuku, and Hauʻula), 14 July 2005.

[34] “MPHS explores old Laie cemeteries,” Kaleo: Koʻolauloa News, December 2007, 2. See “Temple Hill Update: Laie Residents and HRI Unite to Improve Temple Cemeteries,” Hukilau O Laie: Pulling Together for Laie (newsletter published by Hawaii Reserves Inc.), July 1994, 2.

[35] “Workers Restore Old LDS Cemetery,” Hawaii LDS News, January 1989, 6.

[36] See Wayne Yoshimura, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 16 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[37] See James B. Allen, “Technology and the Church: A Steady Revolution,” Church Almanac, 2007, 149. Allen added that such shortages of names were reduced in the late 1950s as the Church began gathering large amounts of raw genealogical data on microfilm that did not require submission by a family representative.

[38] See “Automated Recording in Salt Lake Temple Begins,” Ensign, May 1981, 99–102.

[39] See Allen, “Technology and the Church,” 152.

[40] See Allen, “Technology and the Church,” 153. See also Trent Toone, “How technology revolutionized family history work in recent decades,” Deseret News, 28 March 2017.

[41] Hawaii Temple, annual historical reports, 1991, CHL.

[42] Hawaii Temple, annual historical reports, 1991, CHL.

[43] Alice Ho, interview by Michael Foley, 24 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[44] Hawaii Temple, annual historical reports, 1991 and 1995, CHL. Special thanks to Wayne Yoshimura, long-time Laie Hawaii Temple Recorder.

[45] Hawaii Temple, annual historical reports, 1994, CHL.

[46] Eric B. Shumway to author, email, 17 September 2018.

[47] Mary Adamski, “President of Temple Carries Great Honor,” Star-Bulletin, 4 October 1997, A-4.

[48] T. David and Carolyn Hannemann, interview by Mike Foley and Clinton D. Christensen, 15 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[49] See Hannemann, interview.

[50] “LDS Temple Observes Thanksgiving 43 Times,” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa, 20 November 1997.

[51] These all-night anniversary sessions continued for a number of years.

[52] Wayne Yoshimura to author, email, September 20, 2018.

[53] Gordon B. Hinckley, “New Temples to Provide ‘Crowning Blessings’ of the Gospel,” Ensign, May 1998, 87–88.

[54] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1915, 9. Also recorded in the Millennial Star, 4 November 1915, 689–94.

[55] United States Census 2000.

[56] An illustrative example of the kind of member sacrifice that helped bring a temple to Kona is the story of Leroy and Rose Alip. See R. Val Johnson, “A Temple for Kona,” Ensign, April 2010, 46–47.

[57] Philip A. and Olivia Harris, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 11 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[58] Harris, interview.

[59] An official standard for naming all temples was released by the First Presidency nearly a year later. See Church News, “Temples Renamed to Uniform Guidelines,” 16 October 1999, 4.